As families drop their children off at Elsie Whitlow Stokes Community Freedom Public Charter School on a recent October morning—National Hispanic Heritage Month—they are greeted by a small group of staff members and students dancing to cumbia blaring from a boombox. One student dancer wears a purple tank top, emblazoned with the words “The Future Belongs to Girls,” tucked underneath her flowing floral skirt.

Al Proctor, whose daughter is in kindergarten, chose Stokes for its inviting environment. He wanted a small school for his daughter, and visited the school on the recommendation of a current Stokes parent. He was impressed. “Everybody was genuine,” he says. “They were soft-spoken, they were attentive. You felt that they cared, compared to [it being] just a job.”

The familial, open atmosphere Proctor describes is instantly apparent—and is as noticeable as the school’s remarkable diversity. Parents, including many fathers, who are dropping off their children warmly greet each other and the school’s staff with hugs, handshakes, and high-fives. Children are not dressed in uniforms. People roam about freely, with nary a hall pass or visitor badge in sight.

Proctor has formed relationships with many members of the school community. Most days, he talks fantasy football with the security guard. He volunteers on field trips with his daughter’s class; most recently, he chaperoned a trip to a pumpkin patch.

Stokes parents like Proctor feel connected to staff beyond perfunctory, transactional relationships. Parents consistently name community as one of the main reasons they chose Stokes for their children. This sort of community, they say, is difficult to find in other schools.

Nicole Fitzgerald, whose daughters are in first grade and pre-kindergarten, says that she was drawn to the school by its sense of community even more than by its language program. (Both of her daughters are studying French.) “It [is] more than just a school,” she says. “People [work] really hard to be kind to each other.”

Radhia Latif, a mother to a fourth-grade Spanish student, echoes this sentiment. “You feel like you know the staff.”

Though his child has only attended Stokes since August, Proctor feels an emotional bond to the school. “It’s just heartwarming when you come in here,” he says.

The Exceptional Quality of Elsie Whitlow Stokes Community Freedom Public Charter School

Stokes is considered to be the elder statesman among dual-language public charter elementary schools in Washington, D.C. It is old by charter school standards: Stokes was founded in 1998, well before the charter school boom of the 2000s, with just thirty-five students. It now serves 485 students in pre-K to fifth grade across two campuses in the Brookland and East End neighborhoods.

Key to understanding Stokes is its mission “to prepare culturally diverse elementary school students to be leaders, scholars, and responsible citizens who are committed to social justice.” A focus on diversity runs throughout the school’s work across many domains, including student enrollment, staff recruitment, and curriculum development. In their twenty-year review of the school, the DC Public Charter School Board called Stokes “among the most racially integrated public schools in the District.”

Admission into the school is highly coveted. The DC Public Charter School Board categorized it as a Tier 1 school—the highest ranking a charter school can receive—based on factors including students’ test scores, attendance, and re-enrollment rates. Stokes has 1,827 students on its waitlist—the longest of any school in the District.1 There are currently fourteen public schools that have dual-language programs in the District of Columbia, but Stokes is the only one that offers both French and Spanish.2 Additionally, unlike at many D.C. schools, Stokes students take art or music every day.

Stokes is one of a group of five high-performing language immersion charter elementary schools—along with DC Bilingual, Latin American Montessori Bilingual, Mundo Verde, and Washington Yu Ying—that started the District of Columbia International School (DCI) to satisfy demand for a dual-language program serving sixth through twelfth grades. DCI is one of only two public high schools in the city that offer a language immersion program.

Diverse Charter Schools

Read more about diverse charters schools from The Century Foundation below.Anti-CRT Movement Seeks a Future in Charter Schools

Strategies for Fostering Intergroup Contact in Diverse Schools

Strategies for Promoting Integrated Classrooms within a School

Strategies for Creating and Sustaining School Diversity

Albuquerque Sign Language Academy

How Can the Federal Government Support Integration in Charter Schools?

Scoring States on Charter School Integration

Advancing Intentional Equity in Charter Schools

Fostering Intergroup Contact in Diverse Schools

Integrating Classrooms and Reducing Academic Tracking

History and Demographics of Stokes

In 1996, Congress passed a law allowing charter schools to open in Washington, D.C. That same year saw two major developments in the life of Linda Moore, the school’s founder: her mother, Elsie Whitlow Stokes, who had taught first grade for thirty-six years, passed away; additionally, Moore’s first grandchild was about to be born. Moore wanted to honor her mother’s legacy and thought a lot about what she wanted her grandson’s educational experience to be like.

Moore was interested in starting her own school, but did not wish to spend the majority of her time fundraising. She wanted to create a school that was welcoming to children of varied socioeconomic backgrounds. In an interview with Education Week, Moore said, “Charter schools seemed like a way to get it done, and frankly I was attracted to the whole idea of autonomy with accountability.”3 She decided to found a school. In 1998, the school began with thirty-five predominantly low-income African-American and Latinx students and other immigrant students in the basement of a church in D.C.’s Mount Pleasant neighborhood.

Parents consistently name community as one of the main reasons they chose Stokes for their children. This sort of community, they say, is difficult to find in other schools.

After five years—during which Stokes saw its waitlist steadily grow—the school outgrew the basement and moved into a space at 16th Street and Park Road, in D.C.’s Columbia Heights neighborhood. It remained there for another five years, after which Moore commenced a search to purchase a suitable building for further expansion. After a six-year search, the school finally moved into its current home: a former seminary for Augustinian priests with a commercial kitchen. (That kitchen is now used to prepare three meals a day from scratch for students.)

Moore won recognition as a charter school pioneer. In 2013, she was inducted into the National Charter Schools Hall of Fame by the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools. At her induction ceremony, she was celebrated for her commitment to improve the academic achievement of underserved students.

In 2013, due to years of working long hours and successfully finding a permanent facility in Brookland, Moore stepped down as executive director. Stokes’s Board of Directors selected Erika Bryant, Moore’s daughter, to assume the leadership role at the school. Before Bryant assumed her position at Stokes, she previously worked as the school’s managing director and its operations director. Before working at the school, Bryant spent ten years working in education policy and international development throughout West Africa. This experience has deeply influenced the school’s recruitment strategies, pedagogy, community building, and emphasis on culturally responsive instruction. Bryant is mindful of hiring teachers from West Africa, reaching out to immigrant families from the region, and broadening ideas as to what constitutes the Francophone world for students and their parents.

Shifting Demographics

Over the years, the demographics of the student population at Stokes have evolved as a result of moving locations, a changing city, and intentional outreach. During the school’s first five years, when it was located in Mount Pleasant, Stokes served a majority low-income student body predominantly composed of black and Latinx students.

Serving a socioeconomically diverse group of students was part of Linda Moore’s founding vision for the school, and when the school moved to Brookland, a neighborhood that historically had many black families, it started to enroll more middle-class black students. In its new Brookland location, Stokes also had to work to maintain enrollment of Latinx students, many of whom lived near the school’s old neighborhood. Stokes provided transportation from Mount Pleasant to the new school for five years after the move in an effort to help retain families. Over the past eight years, as the white population in the school’s neighborhood (and the school’s reputation) have grown, white enrollment at the school has increased from less than 5 percent in the school’s beginnings to just under 25 percent currently.

The growing white population is not limited to the school’s immediate neighborhood; over the past decade, the city as a whole has become increasingly gentrified, with a result significant demographic shift. In 1980, 70 percent of the city’s population was black; by 2010, that figure had fallen to 51 percent.4 Since 2015, the city has no longer had a black majority; additionally, black population growth now lags well behind that of other racial groups. (Census data shows that from 2010 to 2015, the number of white residents in the District increased by 16.85 percent, compared to 4.41 percent for blacks;5 from 2010 to 2012, the Latinx population jumped by 14.6 percent and Asian residents grew 9.9 percent.6)

Unlike at many D.C. schools, Stokes students take art or music every day.

Today, the 350 students at the Brookland campus are 38.9 percent black, 24.9 percent Latinx, 24.3 percent white, and 12.6 percent multiracial. According to government definitions, 52 percent are considered economically disadvantaged (that is, they are identified as homeless or in foster care or come from families who earn up to 185 percent of the poverty line). Stokes’s English-language learner and special education populations are 11.7 percent and 10.6 percent, respectively. Students who are considered “at-risk” (an amalgamated category, comprising students who qualify for Temporary Assistance Needy Families or Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits, are homeless, or in the foster system) hovers at 12.9 percent.7

The percentages of low-income students at all of the city’s dual-language charter schools—including Stokes—are lower than those served by DCPS. In the D.C. public school district, which does not include charters, English-language learners comprise 14 percent of the student population, special education students 14 percent, and Latinx students 20 percent. About 44 percent of the nearly 100,000 District students in traditional public and charter schools are considered at-risk.8 Districtwide, 77 percent of DCPS students are economically disadvantaged.9

Among language immersion charter schools in the District, the percentage of low-income students at Stokes places the school in the middle of the pack. (The numbers range from 69.1 percent at DC Bilingual to 10.5 percent at Yu Ying.) A higher percentage of affluent families apply to these schools because charter school admissions in Washington are open to students across the city. Charter schools’ student populations are not necessarily determined by the demographics of their immediate neighborhoods.

Indeed, these schools’ student demographics reveal a troubling pattern: the schools with the longest waitlists—that is, the schools that are considered most desirable—tend to have much higher percentages of wealthier white students. (It is also noteworthy that only 24 percent of the District’s English language learners, who are predominantly low-income and nearly 75 percent of whom speak Spanish, are enrolled at these dual-language schools, most of which teach in both English and Spanish.10)

The figures for racial and socioeconomic diversity are even lower at the most sought-after DCPS schools when compared to dual-language charter schools. At over 1,500 students, for instance, the waitlist at School Within School-Goding has the longest waitlist of all DCPS schools—and it is nearly 70 percent white, with only 4 percent low-income students.11 Capitol Hill Montessori’s waitlist has over 1,307 names; the school is 65 percent black and 29 percent economically disadvantaged. Third is Brent Elementary School, with 1,112 students on the waitlist. It is 66 percent white and 6 percent low-income.

The declining numbers of low-income, black, and Latinx families at Stokes, Bryant says, are in part due to the school’s relocation. “It’s a combination of factors. We moved from an area where there used to be a significant number of Spanish-speaking and low-income families, and we moved into an area that had a larger middle-class. Gentrification in the district has also impacted the school’s demographics,” she says.

Student Recruitment

School leaders are aware that intentional work is needed to ensure diverse enrollment—both now and in the future—with particular attention paid to ensuring that low-income students and English language learners are well-represented.

Stokes’s goal is to maintain or slightly increase its current levels of diversity by having at least 50 percent of its students come from low-income families, 15 to 25 percent of its students be English language learners, and at least 10 percent qualify for special education. It aims to have the student population be roughly reflective of the District’s population, with an oversampling of Latinx students. Stokes’s goal for enrollment of low-income students is below that of public school enrollment in the District—but close to the economic makeup of the entire child population in the District, including children too young to be enrolled in school.

A number of charter schools across the country, such as DSST Public Schools in Denver and Blackstone Valley Prep in Rhode Island, use weighted lotteries to help ensure diversity in enrollment. However, the DC Public Charter School Board has generally interpreted the state’s charter school law as prohibiting any lottery preferences other than those specifically accepted by law (for example, siblings, children of staff or founding board members, or—in select schools—students with an Individualized Educational Plan).

Over the years, the demographics of the student population at Stokes have evolved as a result of moving locations, a changing city, and intentional outreach.

Without a weighted lottery, Stokes has to use targeted recruitment as its main tool for enrolling a diverse student body. Staff visit education fairs throughout the District, embassies of French- and Spanish-speaking countries, churches, civic associations, domestic abuse shelters, the District of Columbia General Hospital, and West African communities. It also advertises in local Spanish-language media. In the school’s early years, staff went knocking door to door to talk to families.

Bryant does not let Stokes’s long waitlist deter her and staff from aggressive recruitment. “You have to go out and be present in communities you want to have represented in your school. You have to connect with people,” she explains.

Staff Recruitment and Retention

Bryant says another key to achieving the student diversity Stokes is known for is having diverse leadership and faculty. Bryant herself is black (which is particularly notable given that 78 percent of public school principals nationwide are white12); the school’s two campus directors of teaching and learning, Constanza Rosas and David Bravo, are both Latinx.

“Making more of an effort to have a staff that represents the kids in the school goes a long way towards diversifying a school—especially for a charter school—because if parents and families see that you make that effort, then they know that it’s more than likely a place where their kids will be accepted and respected and honored,” Bryant says.

Whereas the teaching workforce in the United States is overwhelmingly white and female, Stokes’s teachers are a balance of male and female. The French and Spanish teaching staff comprise largely native speakers of these languages, and hail from Belgium, Canada, Chile, Colombia, the Dominican Republic, France, the Ivory Coast, Mali, Niger, Senegal, and more.

“We are not delivering a French government curriculum here,” Bryant says. “We want our staff and curriculum to be reflective of la Francophonie, which includes Africa, Europe, and the Caribbean.”

She has no patience for those who bemoan the efforts required to hire a diverse staff.

“One thing I’ve heard from other charter leaders when they talk about diversity among staff is that it’s just too hard to do. It’s hard work, but it can be done. You’ve got to make your connections, [whether that] means going to HBCUs, schools of education, [or] tapping into associations.”

Two favored pipelines for Stokes’s student teachers are the nearby schools of education at Howard University and the Catholic University of America. Stokes also recruits potential teachers from the Center for Inspired Teaching, a residency-based teaching fellowship in Washington, D.C. Yet another source is the Carlos Rosario International Public Charter School, an adult education program for immigrants which has a bilingual paraprofessional teaching prep program.

The school’s familial atmosphere also helps. A powerful means of recruitment for Stokes is social networking—friends of friends or mining the personal relationships of school employees, including blood relations and spouses. Recruitment is a team effort; staff must be willing to make connections, too.

That extended family brought childhood friends Costanza Rosas, Stokes’ director of teaching and learning at its Brookland campus, and Ana Maria Donado, its family engagement coordinator. Rosas’ mother, Dora Porras, was a beloved Spanish teacher at Stokes for many years. She also taught Rosas and Donado in their native Colombia. Rosas was an architect who, inspired by her mother, switched to a teaching career; she has been at Stokes for eighteen years. Porras initially brought on Donado nineteen years ago to teach. Donado switched to her current role three years ago.

Among language immersion charter schools in the District, the percentage of low-income students at Stokes places the school in the middle of the pack.

Another unusual characteristic of the school is the number of staff who are parents of current and former students. (In accordance with the local charter law, Stokes offers an enrollment preference for children of employees which is capped at 10 percent of total enrollment.) Some teachers first experienced Stokes first as parents. These include Karim Ewing-Boyd, who has been at Stokes for over thirteen years and is now the director of the East End campus, where he leads the school’s IB accreditation; Everett Richardson, director of special education, whose twenty-year-old son attended the school and whose five-year-old daughter is in kindergarten; and Reggie Alston, a learning specialist, whose son is now enrolled at DCI and whose daughter is in fourth grade. His son’s best friends, also Stokes graduates, both have younger brothers who are in the same class as his daughter. It is not uncommon to see multiple siblings attend Stokes or the school’s adult alumni, send their children there. Yet another phenomenon is the hiring of alumni as teachers: Jay Braithwaite, the physical education teacher assistant at the Brookland campus, for instance, graduated from the school in 2007.

Stokes boasts exceptionally high teacher retention rates. Last year, for instance, it kept 95 percent of its teachers. The key, Bryant says, is to find opportunities to develop staff into roles they would like—or, if those don’t yet exist, wait until the time is right to create them.

“Invest in your employees,” she advises. “Talk to them about what they want to do when they grow up and provide a path for them to do that.”

Ewing-Boyd, the East End campus director, is one of those employees. He began as a teacher and steadily accumulated increasing responsibility. Bobby Caballero, director of student support, started as a long-term first-grade substitute teacher and is now entering his nineteenth year at Stokes. This same pattern applies to non-teaching staff as well: Fresia Cortes was an administrative assistant who is now the director of operations at the new campus; she has been with Stokes for eighteen years. Their stories are prevalent; multiple staff members have been at the school for at least a decade.

Without a weighted lottery, Stokes has to use targeted recruitment as its main tool for enrolling a diverse student body.

Additionally, Stokes develops its teaching assistants to become lead classroom teachers. One pre-K teacher at the East End campus began working in the school’s after-care program as a high school student, continued through college, joined the Stokes staff as an administrative assistant, and then, when she expressed interest in teaching, enrolled at the Center for Inspired Teaching where she is earning her master’s degree.

The challenge, Ewing-Boyd says, is “making sure our human resources pipelines continue to fit our expanded presence. It’s hard to find really good teachers. It gets even more difficult to find really good teachers who are native Spanish speakers. And it gets incredibly difficult to find really good teachers who are native French speakers because this hemisphere does not have a lot of Francophones. This city doesn’t have a lot of Francophones.”

Stokes’s Unique Approach

Stokes has a tightly-knit school culture devoted to multiculturalism, community spirit, and social justice. The school’s commitment to diversity carries over into various aspects of the school, including its classroom libraries, curricula, social activities, and partnerships with local organizations—as well as the sometimes tough conversations that arise when people from many walks of life conflict with each other. Caballero related a story of a white parent asking a black French teacher where she learned to speak the language and what generation she belonged to.

Immersion

The dual immersion language curriculum is what sets Stokes apart.

Pre-kindergarten students are taught in their foreign language 90 percent of the time from the age of three in order to get them acclimated quickly. At this age, Marcia Lue Chung, a kindergarten Spanish teacher from the Dominican Republic in her fifth year at Stokes, says students are pre-operational.

“They are acquiring the language, but not necessarily producing it,” she says. “That’s why you’ll hear kids using mixed language. It’s one of the mechanisms that tells you a foreign language is taking its place in the brain.”

Acquisition continues into kindergarten, when instruction in French or Spanish decreases to 50 percent. By age six or seven, students typically become fully operational in the target language. Thus, proficiency is tracked using the STAMP Assessment, an online evaluation that tests students in second and fifth grades on reading, writing, speaking, and listening. To assess students learning French, Stokes has also administersed the DELF (Diplôme d’Etudes en Langue Française), an official qualification awarded by the French Ministry of Education to certify the competency of candidates from outside of France.

By age six or seven, students typically become fully operational in the target language.

“What happens is by the end of kindergarten, they should be reading at Level C in the target language, books that [require knowledge of] decoding strategies as well as sight words,” says Chung. “But it’s not only reading per se [that we focus on,] it’s also comprehension.”

The school carefully chooses books, Chung says, and prefers “books that come from the place where the language is spoken.” These books are challenging to find in the United States. Teachers are perennially on the lookout for books and other curricular materials that are not European. One carried a copy of Akissi, by Marguerite Abouet, about a mischievous little girl in the Ivory Coast.

Writing in the target language begins in kindergarten. “I will provide them with some sentence starters and I make sure they know that in English, it means X, Y, and Z,” Chung says. “We create word walls and I teach them how to use them, so they have that vocabulary accessible and can write independently.”

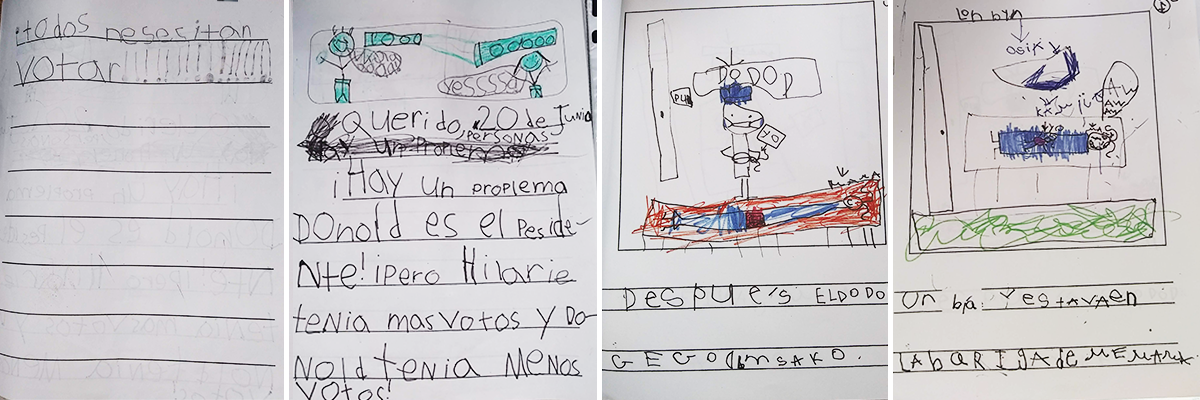

The results can be both funny and profound. Chung shares examples of her kindergarten students’ work:

Hay un problema!

Donold es el presidente! Hilarie tenia mas votos y Donold tenia menos votos.

Todos nesesitan votar!!!

Translation:

There is a problem!

Donald is the president! Hillary had more votes and Donald had fewer votes.

Everyone needs to vote!

Another example is less political in nature:

Un bia yegtava en la bariga de me mama.

Despue’s el dodod gego m sako.

Al final, mi mama fue a casa.

Translation:

One day I was in my mother’s belly.

Then the doctor arrived and took me out.

Finally, my mother went home.

Misspellings aside, students show they are able to express themselves, structure sentences, make a point, and tell a story.

In one pre-kindergarten Spanish immersion classroom, students already demonstrate a good understanding of the language. Ana Carolina Hernandez calls upon students to ask them which class duty they would like to help with that day (“Con qué quieres ayudar el día de hoy?”). A student named Chris understands the question but struggles to supply a response in Spanish. The teacher has him repeat her sentence word by word: “Yo quiero ser el líder de la línea” (“I want to be the line leader”). The next student she calls upon, Henry, needs no assistance. He rattles off, “Yo quiero ayudar con el almuerzo” (“I want to help with lunch”).

The culmination of the immersion curriculum is a week-long study tour of either Panama or Martinique for fifth graders. In preparation for their trip, students study the country’s literature, history, music, and biology, and write a personal narrative about a topic of interest—such as food, dance, or beaches—pertaining to the country.

Georgette Blay, a fifth-grade French teacher originally from the Ivory Coast and educated in France, accompanies the students to Martinique. She is in her eleventh year of teaching at Stokes (and says that her seventy-five-minute commute is worth it because she feels appreciated at the school.)

“Being in a school where the foreign language is valued is a good thing,” she says. “Learning a second language at this age is an asset for the child. Speaking only one language is not competitive.”

Community

Lunchtime at Stokes is orderly yet cheerful. Children stand in lines to receive their meals. Girls are interspersed with boys. Tables reflect the school’s diversity; children easily mix with one another. A student hugs a kitchen worker as he carries trays of food through the small cafeteria. The Green Team, a group of students tasked to clean up the room after lunch, collect food from other students to compost, trash, or recycle.

Stokes’s values are recited at the daily morning meeting of the entire school: “I will: take care of myself, take care of others, take care of my community.” The scene at lunch represents this ethos.

These values are taken seriously throughout the rest of the day as well. Richelle Chapman, a third-grade English teacher, talks to her class about an incident in which students sneaked drinks from the water fountain as they walked up the stairs in line to return to their room, which cost them several minutes of class time. It is a repeat offense that has built up to a sizable chunk of lost instruction time. The incident, Chapman explains, goes against the school values of personal responsibility, as well as ensuring that others follow the rules as well. One girl, the first student who stopped for water, cries at this gentle admonishment. Chapman asks students for potential solutions; the idea of students carrying their own water bottles is suggested.

Making more of an effort to have a staff that represents the kids in the school goes a long way towards diversifying a school—especially for a charter school

Instilling students with a sense of individual responsibility affects how they approach school, says Chapman. “I think about things in the big picture way where we’re planting the seeds for later,” she says. “We teach children that they can take control of their education and of their learning, and that they need to be just as active as their teachers and parents in this regard because it’s something that will benefit them in the long run.”

Water incident notwithstanding, peace generally reigns at Stokes. Richardson, the director of special education, says, “You haven’t seen kids running around here cursing and screaming, fighting, beating up each other. We are so far from that.”

Because of the school’s diversity, students are unaware of their differences from one another. An atmosphere of tolerance and acceptance is instilled into them from the day they set foot onto campus.

Stokes offers a daily after care program until six in the evening which provides a meal and a host of activities ranging from tennis, chess, to playing in a steel drum ensemble. This program costs between $60 to $90 a week, based on family income, and is partially funded by grants. Several of its programs are taught by college students, including Stokes alumni. One fifth-grade student volunteers every Friday to help watch her younger peers in pre-kindergarten and kindergarten during after care. She is running for secretary of the school’s student government and is praised by administrators for her strong sense of responsibility and leadership.

“It doesn’t matter who you are or if I don’t know you, if you get hurt, I can help you,” she says.

Stokes staff pay careful attention to students who might require additional assistance and initiate partnerships with community organizations who can be of help. Caballero coordinates resources for homeless families. The school has a relationship with Mary House, a shelter for needy and immigrant families, to help provide housing. A family who lost a child to gun violence was connected by staff to the Wendt Center for Loss and Healing. A partnership with the social services charity Martha’s Table offers meals to families facing food insecurity.

Stokes boasts exceptionally high teacher retention rates. Last year, for instance, it kept 95 percent of its teachers.

Stokes’s leadership has ensured that men of color abound at the school and it is intentional. For boys who lack fathers at home, says Alston, they can be lifelines. “It’s a beacon that they come to sometimes.”

Not only is Caballero a longtime administrator, but his son is a first-grader at Stokes. Two of his son’s classmates also have fathers who work at the school. “Behavior starts with relationships,” says Caballero, a much-adored figure at Stokes who is known as “Mr. Bobby.”

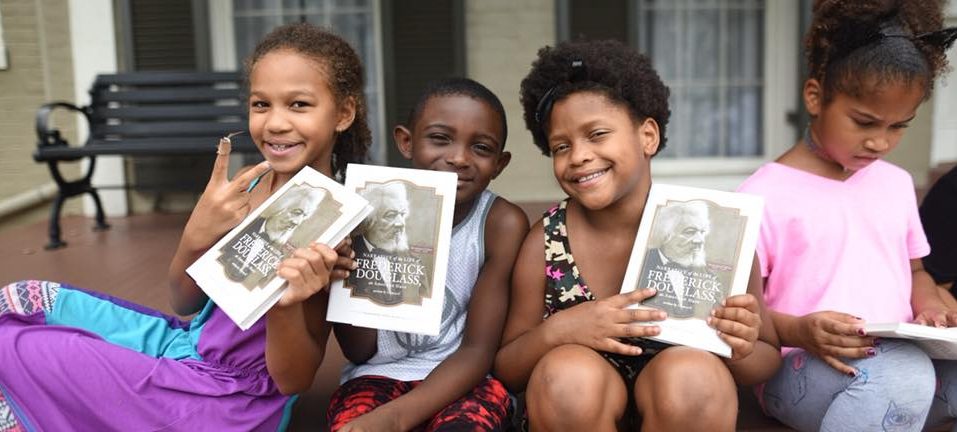

Mr. Bobby’s influence runs far and wide. When he began working at Stokes, the school had high suspension rates for boys of color. He substantially reduced them and, as part of his efforts to do so, started a book club for boys who were suspended. Though the school already has many involved fathers, he also actively recruits more to participate in school activities.

Social Justice

Woven throughout Stokes’s curriculum and school culture is not only a goal to instill an appreciation of difference in students, but an insistence of having them engage with it meaningfully—even if it sparks conflict.

Two years ago, fifth graders staged a “Love Trumps Hate” walkout on Valentine’s Day that drew over 200 students to protest the then newly elected president over his views against undocumented people and people of color. Students contacted media to cover the event, which aroused complaints from of some parents who preferred to keep politics out of the classroom.

However, Bryant is clear about her school’s mandate. “Freedom is in the name of the school intentionally,” she says. She emphasizes that allows for the freedom to protest.

The city’s demographic shift has had consequences for Stokes as its student population has become increasingly white and affluent. Multiple staff members have voiced concerns that incoming parents see Stokes as a “hip language school” rather than an institution with a strong social justice mission.

Bryant says the school stresses to parents that social justice lies at the heart of everything it does. “One of the things that we are trying to work harder at is to make sure that when people apply to the school, they know exactly who we are and what we stand for, because the piece about freedom and social justice is not just lip service,” she says. “It is who we are, it is what we believe in, it is what we owe in part to our kids.”

The school’s commitment to diversity carries over into various aspects of the school, including its classroom libraries, curricula, social activities, and partnerships with local organizations—as well as the sometimes tough conversations that arise when people from many walks of life conflict with each other.

Alston, a Stokes parent and teacher, admits that he finds some classroom material can be difficult to embrace. When his son was enrolled at the school, he was assigned to write a paper on the immigration patterns of children from El Salvador. In the course of his research, he encountered articles discussing rape. Alston was uncomfortable with his son reading such harrowing information, but also values the fact that students learn about political strife all over the world. A Stokes education has been as instructive for Alston as for his children.

“When you have your child coming to Stokes, there are going to be conversations you don’t agree with politically or religiously. I think I’ve grown as an adult being here, not just my kids. Education is never going to be just reading, writing, Spanish—it has to be world knowledge.”

The school does not shy away from discussing controversial topics. One recent morning meeting featured a slideshow featuring images of Colin Kaepernick kneeling on a football field; another people holding rainbow flags. Both garnered pushback from parents, as did classroom discussions of families with gay parents.

Alston says the high political engagement at school prompts parents to be engaged. “It forces you to be an active parent. . . . You have to have that conversation.”

The school also encourages parents to engage with each other. The school hosts parent events every month where families can mix and mingle. Families new to Stokes are paired with existing families to orient them to the school. Though tensions do exist, parents agree that the school’s focus on social justice is one of its most outstanding characteristics.

Says Alston, “This is a school where I’m going to make myself better, my community better, and those around me better.”

Growing Pains and Opportunities

Cultivating Diversity as Enrollment Grows

In September 2018, the schools opened a second site in D.C.’s East End neighborhood, serving 140 pre-kindergarten and kindergarten students, and plans to add a grade every year until fifth grade. The new site is co-located with Maya Angelou Public Charter School and can accommodate up to 400 students.

When Stokes decided to open a second site, it chose to do so in Ward 7—which has one of the city’s highest shares of children under the age of 5, and one of the lowest median family incomes—to counter the increasing percentage of white affluent students at its other campus.

Thus it was shocking when fewer black children and fewer low-income families enrolled at East End than anticipated. The East End campus is 55 percent black, 17 percent Latinx, 15 percent white, 1 percent Asian, and the rest identifies as multiracial.

With a new campus and new parents, Ewing-Boyd finds himself negotiating tensions akin to those at the Brookland location. “We have parents who don’t understand that if you’re coming from a position of privilege in this society, I’m less concerned about your fears of being in Ward 7. Your fears for the safety of your child are misplaced. You’re responding to the untruths that are told about the community.”

When Stokes decided to open a second site, it chose to do so in Ward 7—which has one of the city’s highest shares of children under the age of 5, and one of the lowest median family incomes—to counter the increasing percentage of white affluent students at its other campus.

Bryant believes the best way to address these conflicts is to confront them. “We want to do this more with families, but we’ve definitely started with staff. . . . We acknowledge the tension that comes from having such a diverse group of people. We know it’s there, there’s no way around it, because we all come to the table with different expectations and cultural norms. What we have been trying to do—probably since the inception of this school, but we’ve been very intentional the past few years because of the changing demographic in the school—is just bringing that out to the forefront.”

Stokes is considering how to proceed in the future. The school has begun exploring whether to add a middle school and whether it can serve children younger than pre-kindergarten. Bryant is also considering adding a daycare center for staff, purchasing land to build a working farm for science experiments and to grow food, adding other countries to fifth graders’ study abroad itineraries, and tracking alumni after they graduate from Stokes.

Addressing Achievement Gaps

Although it has been very successful closing achievement gaps between black and white students, Stokes has struggled to do the same for Latinx students.

On the national Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers (PARCC) exams, Stokes students as a whole outperform the District of Columbia in both English Language Arts (ELA) and math. (In English, 67 percent of Stokes students met or exceeded expectation, versus 56 percent for the rest of the city; in math, the rates are 69 percent for Stokes versus 54 percent elsewhere.13) Broken down by subgroup, Stokes has shown particular success with black students. Achievement gaps between black and white students on PARCC tests are much narrower at Stokes than in the rest of the city. Black students at Stokes met proficiency 26 percent higher on math and 21 percent on ELA compared to those throughout the rest of the District.

However, white and Latinx students at Stokes score more poorly than their peers in the city overall; 95 percent of white students throughout the city met or exceeded expectations on ELA versus 92 percent at Stokes; in math, the District’s figure is 14 percent higher than that of Stokes, 94.8 percent compared to 80.6 percent at Stokes.

In ELA, 57 percent of Latinx students across the city are considered proficient or advanced; this is true for 53 percent of Latinx students at Stokes. In math, the rates are 55 percent across the city versus 50 percent at Stokes. (According to Stokes’s data, 49 percent of its Latinx students who took the PARCC last year were either English-language learners or special education; nineteen percent were both.)

There is mixed success for the school’s at-risk students, English-language learners, and special education students. At-risk students in the District scored over 7 percent higher than Stokes students in ELA (42.7 percent versus 35 percent) but comparably in math (both were about 40 percent.) English-language learners at Stokes scored higher in ELA than the District overall (42.9 percent versus 41.4 percent) but lower in math (42.9 percent versus 46.3 percent). Finally, special education students at Stokes scored over 21 percent higher above the District in math (40.9 percent versus 19.3 percent), but below in ELA (17.9 percent for the District versus 13.6 percent at Stokes).14

To address these gaps, the school recently transitioned to using the International Baccalaureate (IB) Primary Years Programme (PYP), a curriculum which emphasizes conceptual understanding and higher order thinking skills. The school is currently pursuing accreditation from IB, which will send a team to inspect the school in the spring. Before the switch to IB, there was a lack of uniformity across curriculum and teachers had great leeway in what they taught. Now, however, teachers adhere to the IB’s units of inquiry, in which each unit is a six- to eight-week exploration of a broad concept.

In this curriculum, students explore interdisciplinary themes guided by a central topic and idea. For example, one unit of inquiry for all grades is “How we organize ourselves.” Fifth graders study war to examine how “People have different perspectives on the use of force to resolve differences.” Pre-kindergarten students study buildings to understand how they are constructed so people have places to live, work, and play.”

In 2017, Rebecca Courouble was hired as Stokes’s PYP coordinator and the school’s first pre-kindergarten instructional coach. She, along with two other coaches, meets with teachers every week to reflect on students’ struggles and successes with the units of inquiry and to agree upon pedagogical goals for the coming week. Courouble also observes teachers in their classrooms using an evaluation rubric to advise them on how they can improve their practice. Though the transition to having a “culture of coaching” has not been smooth, she says that teachers are now coming around to the idea.

Conclusion

The leadership of Elsie Whitlow Stokes Community Freedom Public Charter School is not content to rest on their laurels, and, going forward, are focusing on three main initiatives: maintaining its foothold in black and Latinx communities as the District’s demographics continue to change, improving academic achievement of its Latinx students, and ensuring that its curricula are structured and conceptually based.

Despite its challenges, however, the school has much to be proud of. Due to its tight school culture centered on a mission of social justice, community, global awareness, cultural savvy, and diversity, the school has become one of the most distinctive in Washington—and in the nation. Because staff members are aligned on the school’s values, students have internalized them as well. The school’s remarkable diversity is so ingrained that students have no idea the composition of their school is noteworthy. Difference surrounds them so often they fail to recognize it as such.

What students do recognize, however, is that their school is a place they want to be. In the words of eight-year-old Kofi: “They’re such good teachers that teach you such good things. Sometimes it’s not even about French, sometimes it’s about life—what’s good about it, what you shouldn’t do and what you should do, and how to get along with people.”

Editor’s Note: Pseudonyms were used for some of the students named in this piece.

Notes

- “Dual language charter schools attract the longest waiting lists in D.C.,” The Washington Post, April 17, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/education/dual-language-charter-schools-attract-the-longest-waiting-lists-in-dc/2018/04/17/b652312c-427c-11e8-ad8f-27a8c409298b_story.html.

- “Immersion Programs in DC,” DC Language Immersion Project, http://dcimmersion.org/dual-language-schools-dc/.

- Katie Ash, “Q&A with Linda Moore, Charter School Hall of Fame Inductee,” Education Week, July 2, 2013, http://blogs.edweek.org/edweek/charterschoice/2013/07/qa_with_linda_moore_charter_school_hall_of_fame_inductee.html.

- “Washington, DC: Our Changing City, Chapter 1: Demographics,” Urban Institute, http://apps.urban.org/features/OurChangingCity/demographics/#race.

- Stephen Hudson, “DC’s Black population is growing, but there’s more to the story than that,” Greater Greater Washington, January 25, 2017, https://ggwash.org/view/62108/dcs-Black-population-is-growing-but-this-doesn-tell-the-whole-story.

- Matt Connolly, “DC area outpaces nation in booming Asian, Hispanic growth,” Washington Examiner, June 12, 2013, https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/dc-area-outpaces-nation-in-booming-asian-hispanic-growth.

- DC Public Charter School Board, Elsie Whitlow Stokes Community PCS–Brookland, school profile, https://www.dcpcsb.org/school/elsie-whitlow-stokes-community-freedom-pcs-brookland.

- Perry Stein, “D.C. is misspending millions of dollars intended to help the city’s poorest students,” Washington Post, April 14, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/education/dc-is-misspending-millions-of-dollars-intended-to-help-the-citys-poorest-students/2018/04/14/6006c02a-3788-11e8-9c0a-85d477d9a226_story.html.

- “Fast Facts 2017–2018,” D.C. Public Schools, https://dcps.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/dcps/publication/attachments/DCPS%20Fast%20Facts%202017-18.pdf.

- Tara García Mathewson, “Rising popularity of dual-language education could leave Latinos behind,” The Hechinger Report, July 31, 2017, https://hechingerreport.org/rising-popularity-dual-language-education-leave-latinos-behind/.

- “District of Columbia Public Schools Lottery Results 2018–2019,” D.C. Public Schools, http://enrolldcps.dc.gov/node/61.

- Denisa R. Superville, “Charter Principals Are More Diverse (and Other Highlights From New Federal Data),” Education Week, August 8, 2017, http://blogs.edweek.org/edweek/District_Dossier/2017/08/principals_in_the_charter_sector_are_more_diverse.html.

- “Elsie Whitlow Stokes Community Freedom PCS, Performance Summary,” Learn DC, http://results.osse.dc.gov/school/159/assessment/1/proficiency/3.

- “DC 2018 PARCC Results by by Demographic Groups,” EmpowerK12, https://empowerk12.org/dc-parcc-by-demographics.