Hezbollah is in its most vulnerable position in decades. Since Israel escalated its military campaign against the group in September 2024, Hezbollah has suffered devastating losses—not only militarily but also politically and socially.

Israel’s offensive has killed hundreds of Hezbollah fighters and maimed thousands of operatives, eliminated much of the organization’s senior political and military leadership, including advisors and strategists, and paralyzed the group’s communications and financial infrastructure.

The Israeli attacks incapacitated the strategic core of Hezbollah’s military operations. They also separated the Shia community from the rest of the population and singled out those parts of Hezbollah’s social service organization network as targets. The Israeli assault blurred the distinction between civilian and military to an extreme degree, destroying entire villages and bombing Lebanese from other communities who dared to shelter Shia refugees.1 Entire residential blocks in Hezbollah strongholds have been leveled, and numerous towns and villages in southern Lebanon flattened. The scale and cost of the estimated damages are overwhelming.2

But these are more than material losses. They mark a rupture in Hezbollah’s carefully cultivated image of strategic deterrence and organizational invincibility. Today, Hezbollah’s narrative of victory, dignity, and deterrence—long a cornerstone of its legitimacy—has been deeply shaken.

In response, Hezbollah has turned to symbolic gestures aimed at reinforcing the ethos of the “resistance society,” drawing heavily on the endurance and defiance of a fatigued popular base. Yet as the group scrambles to maintain its legitimacy and recalibrate its strategy, the toll on its support base continues to mount.

This report is based on several weeks of fieldwork in Lebanon this past winter, and informal interviews with dozens of ordinary people (many declined to give their names out of concern for their safety), whose views shed light on the mood and views of Hezbollah’s core communities. Despite the enduring defiance and a mentality of “resistance,” a mixture of shock and despair has overtaken much of Lebanon’s Shia community. Many Hezbollah supporters who still proclaimed pride in the movement simultaneously expressed grief, disillusionment, and a sense of being forsaken by former allies. At the same time, there were few signs that the community had rejected Hezbollah’s core animating beliefs.

There is a growing disconnect—disillusionment with Hezbollah as a party is paired with an even deeper identification with its promotion of “resistance” against Israel. This unique situation offers an object lesson on the limits of military power to change political realities, and hints at a future in which Hezbollah may be radically transformed and weakened, but will remain a rallying point, in some form or another, for a significant portion of Lebanon’s 1.7 million Shia.

Ceasefire as Continuation of War

On November 26, a U.S.-brokered agreement led to a sixty-day ceasefire between Israel and Hezbollah. The deal called for both parties to withdraw their armed forces from southern Lebanon south of the Litani River. The goal was to end hostilities and allow the Lebanese Armed Forces to take full control of the region.

Hezbollah’s new secretary general, Naim Qassem, declared the ceasefire a “great victory that surpasses that of July 2006” because Israel did not achieve its stated aims.3 Hezbollah continues to exist and Israel failed to reoccupy the south, he pointed out. Qassem criticized those who believed that Hezbollah would emerge weakened from the war, emphasizing that the group had not been destroyed. But this triumphant narrative soon collided with realities on the ground.

Despite the agreement, Israel maintained a military presence in more than sixty Lebanese towns and villages in the south. Throughout December and January, Israeli military operations in southern Lebanon continued.4 Drone strikes, artillery shelling, and the demolition of basic infrastructure, farmlands, and homes reached villages like Yaroun, Aitaroun, Khiam, and Houla, among many others.

Israel also delayed its withdrawal from southern Lebanon past the January 26 deadline, citing Lebanon’s failure to deploy its army and ensure Hezbollah’s withdrawal beyond the Litani River. While Israel eventually withdrew on February 18, 2025, five hilltops inside Lebanese territory remained under its control. Lebanon’s new government denounced this open-ended presence, viewing it as an occupation.

An investigative report published on May 7 by The Legal Agenda, a Lebanese policy and research institute, establishes that Israel’s military presence today is not limited to the five points, as is often portrayed in official discourse and the media in Lebanon.5 Rather, Israel has used these points as a lever to reestablish its control and expand the scope of its occupation. New fixed military positions have emerged as a de facto reality. Israel is establishing “an invisible buffer zone,” marked by earthen berms, almost two kilometers wide and along the entire southern border. It also continues to systematically target any reconstruction efforts or reestablishment of life in southern Lebanon.

Paradoxically, the ceasefire allowed Israel to act as enforcer, main violator, and benefactor of the agreement. Many Lebanese, including Hezbollah supporters, see the truce as “a continuation of the war,” evoking memories of the decades-long Israeli occupation of the Lebanese south that Hezbollah helped end in 2000. This time, however, Hezbollah has very little room to maneuver.

Popular Acts of Symbolic Rebellion

After the ceasefire—which followed months of devastating losses—Hezbollah’s remaining leadership still proclaimed “victory.” It was a rhetorical strategy that had worked in the past, such as after the 2006 war with Israel, when Hezbollah suffered disproportionate casualties but claimed, with some credibility, that the war had led to the group strengthening its strategic position. This time around, however, the proclamations of victory rang much hollower for most Lebanese. The party line seemed out of touch with reality.

And yet, even now, the Hezbollah ethos of “resistance” holds cachet for the group’s popular base, which continues to reflect it in their actions.

On the first day of the ceasefire, hundreds of thousands of displaced people celebrated their return to their southern homes.6 Yellow Hezbollah flags flew from car windows, portraits of fallen fighters were raised, and viral videos showed Lebanese civilians tearing down Israeli flags in their reclaimed villages.

As the sixty-day deadline neared—with Israeli withdrawal still uncertain and the Lebanese army hesitant to declare the area secure—many southern families took matters into their own hands. Between January 25 and 27, they staged defiant “return marches,” driving back to their towns despite the continued presence of Israeli tanks and soldiers.7

Videos of unarmed civilians confronting Israeli military vehicles in places like Khiam went viral.

Videos of unarmed civilians confronting Israeli military vehicles in places like Khiam went viral. In several cases, Israeli troops opened fire on displaced Lebanese civilians attempting to return to their homes. Within two months of the ceasefire agreement, Israeli forces had killed at least 57 civilians, injured 120, and destroyed 260 properties.8

Acts of defiance galvanized public sentiment and stirred calls for renewed resistance, revealing a grassroots push that outpaced Hezbollah’s official messaging and measured actions.

Still, it was impossible to deny that this time was different. Resilience has long been an everyday necessity for southerners, but the Lebanese government now appeared to take that resilience for granted, with few official messages of support to the south in the aftermath of the war, or as Israel continued to violate the ceasefire and set up a de facto occupation.9 On the other hand, there were also early signs that some southerners had begun to feel that Hezbollah, long their traditional champions, either took their endurance for granted or no longer had the wherewithal to come close to meeting their needs. For the most part, however, Hezbollah’s base seemed to be taking solace in celebrating the party’s legacy.

Claiming Victory in Death

Two weeks after the ceasefire took effect, the shadow of death and destruction lay heavily across Hezbollah’s traditional heartland: in the south, in cities such as Nabatiyeh, al-Zahrani, and Tyre, and remote residential areas that had been heavily bombarded; and in the southern suburbs of Beirut, which Israel had heavily bombed, and where Hassan Nasrallah, Hezbollah’s long-time secretary general, was assassinated on September 27.

In these Hezbollah strongholds, the burden of sacrifice seemed to weigh heavier than ever. Hezbollah has long glorified the nobleness of sacrifice “for the resistance” and the honor of martyrdom “in the name of the resistance.” But this time, the mix of pride and mourning—already a central ritual in Hezbollah’s culture of resistance—seemed more bitter than in any previous war.

Compared to the war of July 2006—the last major confrontation with Israel—the losses were staggering. The number of Hezbollah fighters killed was several times higher, and nearly the entire senior political and military command was eliminated.

But it wasn’t just the scale of death that felt different. The war had eliminated key symbols of Hezbollah’s power. Hezbollah was still trying to spin the losses as a triumph: Hundreds of banners lined the Sidon–Tyre highway extolling Hezbollah’s sacrifices. One eye-catching banner on a bridge featured fifteen of Hezbollah’s highest-ranking political and military leaders, all now dead, with the message, “In the martyrdom of our leaders, we are victorious.” Nearby, another billboard read: “Through our leaders, our martyrs, we reached victory.” Such banners flooded the highway.

“Sometimes I feel like the whole party is sitting on these billboards,” said a man sipping coffee at a nearby kiosk. His comment captured a common sentiment in the south: many were grieving not only individual leaders but also an entire generation of leaders.

In Nabatiyeh’s historic Ottoman-era marketplace, posters of fallen Hezbollah fighters blanketed every surface. Israeli air raids had destroyed large parts of the market. And yet, intact stores were open and running—even though many no longer had doors. Pictures were draped from balconies, plastered on cars, hung on fences and streetlights, and pinned to the damaged facades of buildings. Atop each crumbled building sat a small yellow flag representing Hezbollah. A giant poster of Ali al-Husseini al-Sistani, an Iraq-based cleric who is probably the world’s most important Shia religious figure—and who has no connection to Hezbollah—wrapped around the ruins of a building, with the caption: “We express our solidarity with our dear and proud Lebanese.”

Through one lens, the scene might have been the height of irony, but speaking to locals revealed that, for most, the flags acted as banners of survival.

This duality of mourning and celebration was central to Hezbollah’s media campaign. It sought to fuse sorrow with triumph and trauma with resilience. The message was clear: even in death, the resistance claims victory. But beneath the surface, the grief was profound. And for many, especially those who had lost loved ones, no banner could fully reconcile that contradiction.

Melancholy and Defiance

The Hezbollah media campaign’s central figure was Nasrallah. Israel assassinated the charismatic leader in Haret Hreik in the southern suburbs of Beirut, using massive bunker-buster bombs that knocked down several multistory apartment buildings. In late November, images of Nasrallah dominated the devastated neighborhood, many accompanied with messages that riffed on his surname, which can be translated as “victory of God.” One common poster featured Nasrallah and Hashem Saffiedine—Hezbollah’s second in command, who was killed by the same strike—and declared: “Here comes the victory of God. The age of defeats is over.”

On November 30, Hezbollah held a memorial gathering at Nasrallah’s assasination site, a first public tribute to its late leader. A large cube projecting lights toward the sky had been erected in the crater. It was surrounded by flickering candles, giant posters of Nasrallah, and Hezbollah’s yellow flag. The Lebanese and Palestinian flags were draped from surrounding buildings.

The site had become a sort of pilgrimage destination for Hezbollah supporters. Mourners leaned against the fence, staring into the giant crater. Others took selfies, flashing the victory sign. One father laughed as he held his baby son’s hand, pulling at his index finger and shaking it—mimicking the signature gesticulation that Nasrallah would make during impassioned speeches.

And then a surreal moment: from the upper balconies of two buildings overlooking the gaping crater, the sound of drilling echoed. Construction workers were busy repairing shattered windows and broken railings. “How do they have the nerve to fix their balconies while this hole down here sits in our hearts?” said one woman, apparently assuming that the construction noises came from private residences.

A twenty-six-year old woman from the coastal town of Khalde, displaced during the war and now working as a manicurist, said she was visiting the memorial site several times a week. “I need to do this because I’m still in disbelief,” she said. “I listen to [Nasrallah’s] speeches whenever I feel down. His voice used to help us feel victorious.”

Many in the Shia community seemed unsure of how or whether to grieve. The devastation exceeded anything they had experienced, at least for several decades. Two moods dominated: melancholy and defiance. What emerged wasn’t calm, but a wounded stillness: shock and sorrow layered over pride, frustration, disillusionment, and isolation.

The contradiction played out on a street in the southern suburbs of Beirut: a man stood silently over a bomb crater, weeping in front of a printed sheet bearing the faces of family members killed in another bunker buster bombing. The sheet was a stark departure from the formal martyr posters typically issued by Hezbollah to honor fallen fighters. A woman walking by laughed bitterly: “Ha! They [the Israelis] think this will scare us.” The man said nothing, his face frozen in disbelief.

Loyalty and Doubt

The specter of loss stalks every corner of southern Lebanon and the southern suburbs of Beirut. Some Hezbollah supporters cited it as they doubled down on their loyalty. Many others had begun to question party narratives.

“I was sitting at a coffee shop the other day in the southern suburbs, and everyone was pointing out where they lost this or that person,” said a 33-year-old woman who lost a close friend in the September 17 pager attacks that maimed thousands of Hezbollah rank and file.10 “I then saw the coffee shop where my friend’s pager exploded in the corner of my eye. I couldn’t take it anymore. I felt death surround me.” Still, she said, she remained a staunch Hezbollah supporter.

At a gathering of a family that had lost several members to the war, the conversation took a different turn, pushing back against the narrative of victory being promoted by Naim Qassem. Within the Shia community—where many support resistance as a duty but not necessarily Hezbollah’s monopoly over that resistance—some challenged the framing of the war.11 They saw it as an attempt to obscure the sheer scale of the calamity.

“Why can’t we be sad?” said a 36-year-old butcher in Beirut. “There were civilians. Should I congratulate people for their deaths? Should we all be congratulating one another?”

“Why can’t we be sad?” said a 36-year-old butcher from al-Noueiry district, a densely populated area in Beirut, which was heavily bombarded during the war. “Can I be weak? Must I always be strong? There were civilians. Should I congratulate people for their deaths? Should we all be congratulating one another?”

A man whose family had deep ties to Hezbollah and who had lost multiple relatives tried to make sense of their deaths. “Although I’m the only critic of Hezbollah in my family, let me tell you: these weren’t just ordinary deaths, not even the civilian ones. In our community, many see these deaths as part of Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah’s martyrdom. For many, it is a source of honor to go down with him as part of a collective sacrifice. Or at least, that’s how our faith understands it.”

For those most directly affected by the war, whose homes, businesses, and lives were upended, there was little energy for political narratives. They were focused on survival.12

Ahmad, a carpenter from the southern suburbs, had his workshop partially destroyed in Israeli bombardment just a day before the ceasefire. When asked about the public debate over victory, he looked weary. “Call it whatever you want,” he said. “Just tell me, who’s going to rebuild my shop? Me. Who will fix my furniture? Me.”

Hezbollah had promised monetary compensation to some victims of bombardment, but Ahmad didn’t receive any.13

They began surveying the area. They are organizing the folders now. Some people got a very small compensation to go rent a place somewhere. But because my shop wasn’t fully destroyed, and it’s not a residential building, I probably won’t get a cent from the party. Honestly, since the ceasefire, I didn’t even have the appetite to fix anything. There is something in the air, I tell you. Like a collective depression. For a month, I just sat there with plastic covering my shop. Only now am I starting to pull myself together. I’m taking on new jobs just to repair my own place of work.

A week later, Ahmad said he’d been thinking about the question of victory and defeat. “We may not be victorious,” he allowed. “This is not victory, but we are still rebelling against defeat. We rebel against defeat. That is what we do.”

“Bravery beyond Criticism”

Ali, an interior designer in his sixties with two children, lost both his homes—one in the southern suburbs and another in his southern hometown. He was skeptical of Hezbollah’s promises of compensation.

Do you know how much my furniture cost me? What’s this money going to do? I don’t think we’ll see a cent. Not anytime soon. They will be very selective this time. Before the war, I was king. I worked for forty years to get to where I am. Then the crisis happened. And then this. I had two homes. Now I have none. . . . I had to beg people in the Druze safe areas to let me rent a place when we got displaced. We’ve been humiliated. How many times can I rebuild?

In Tyre, a coffee shop owner said that he returned during bombardment just to retrieve his equipment. “These machines cost more than the whole shop. No compensation will cover them. This coffee machine alone is $30,000. I was ready to die for it,” he chuckled. “I knew this time was different when I heard they’d assassinated Nasrallah. I said to myself, we’re on our own now. So the first thing I did? I ran under the bombs to get my machine.”

At the time of my visit, his shop stood at the base of an eight-story building that had been struck by precision missiles which had destroyed its top three floors. Although the shattered front windows hadn’t been repaired, the shop was full of people. Thick sheets of plastic covered the entrance—a common sight across all affected neighborhoods.

When people spoke of triumph and victory, almost all pointed to the south and its people—their bravery and sacrifice. They used the term al-malaheem, which translates to epic feats and battles of resistance. They spoke with awe of the acts of bravery “we didn’t see,” “the ones we may never bury,” and “the bravery of our fallen on the borders.” The south became sacred; its fighters lionized.

Even critics of Hezbollah’s domination over the resistance spoke reverently of those who died on the front lines. The political fell away in favor of the personal. “Their bravery is beyond criticism,” one resident from al-Zahrani said. “It is beyond politics.”

“The flyers, they feel like a veil over the martyrs,” he added quietly, pointing to Hezbollah’s planted flags and the flyers draped over the rubble. “I pay my respects to their courage. But beyond that, what can anyone do?”

Isolation and Defiance

Segments of Lebanon’s Shia community expressed growing disillusionment with Hezbollah’s deterrence capability and strategic depth. Many have new doubts about Hezbollah’s decision-making and conduct during the war and its failure to anticipate Israel’s premeditated, deeply penetrative campaign. The group’s misjudgment of Israel’s intelligence reach, surveillance, and internal infiltration revealed significant vulnerabilities.14

At the same time, while some in the Shia community expressed deep frustration with Hezbollah’s miscalculations—going so far, in some cases, as to blame the party for a part of their suffering—few appear to directly blame Hezbollah for joining the regional war on October 8, 2023.

Hasan, a manager of a cafe in Beirut, lives in the southern suburbs. He is a long-time supporter and follower of Hezbollah. He reflected on the contrast between the 2006 war and the current conflict: The Israelis “had artificial intelligence, satellites, surveillance tech, and spies—otherwise they wouldn’t have accomplished anything,” he said. “Truly, it’s not fair. They have everything on their side, and we have villages and bodies.” When Hasan heard that Nasrallah had been assassinated, he collapsed crying, “I still can’t bring myself to see the assassination site, I can’t. I don’t want to face that reality. And I live in the heart of the area.”

Hasan professed his resilience to the destruction. “It wasn’t that bad,” he said. “Yes, you have residential blocks that were fully destroyed, but things around them are all still working. It’s going to take more than that to bring us down.”15 But he also allowed that others in his community felt humiliated by the war—not only from being forced to flee their homes without any place to go, but from the eerie sense that Israeli surveillance knew more about their neighborhoods than they did.16

Ali shared his discomfort: “I’m not Hezbollah or anything like that, but I felt like they [Israel] were in my home even when they weren’t. I hated being made to feel like I was a danger to my own people. Everywhere we sought shelter, people were skeptical or afraid of us; not because we were dangerous, but because Israel made everyone believe we were.” Many other Shia Lebanese expressed a similar sense of isolation.

Nearly every conversation with people in this community included a grim joke: that the Israelis knew what was inside their homes better than they did. “I honestly felt like their announcements were coming from my own living room,” the manicurist from Khalde said, reflecting on the precision of Israeli evacuation orders and maps. (In two months of war, Israel issued more than 136 forced evacuation orders.)17

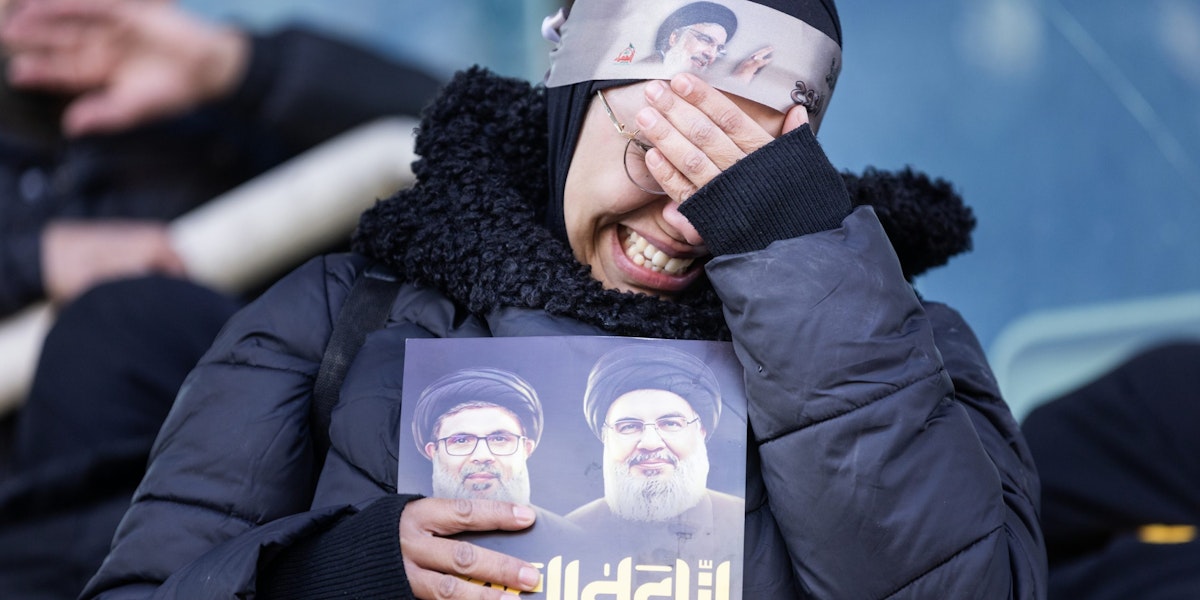

Despite the disillusionment, Hezbollah’s popular base endures. On February 23, five months after Nasrallah’s assassination, hundreds of thousands of people gathered for his funeral procession in Beirut.18 The massive turnout demonstrated that the group’s social base is alive.

But the future is uncertain for Hezbollah. From a military standpoint, it appears that the group has been so degraded that it is unlikely to return to its former might, at least in the near future. Further, Lebanese from the communities that have traditionally backed Hezbollah are exhibiting greater doubts about the group—its leaders, its decision-making, its risk-taking, and its ability to back up its rhetoric and follow through on promises to constituents. There is a grim resignation to the fact that Hezbollah and its mythic leadership—most of them now dead—are not invincible. Further, the number of Hezbollah sympathizers outside of the party’s main constituency in the Shia community is shrinking, and the party is growing more isolated, politically and socially, in ways that will be consequential for future elections. Meanwhile, even the most committed Hezbollah supporters are fatigued, and increasingly skeptical that Hezbollah is capable of providing for their security, return to villages and neighborhoods, and reconstruction.

On the other hand, the war does not seem to have caused a mass questioning of the core tenets of Hezbollah’s ideology. If anything, these communities seem to have bonded in their suffering, clinging to symbolic acts of defiance amid their mourning and the tasks of daily survival. What comes next in southern Lebanon may not resemble the Hezbollah of old, but it will almost surely be built around a deep well of shared grievances and renewed animus for Lebanon’s southern neighbors.

This report is part of “Networks of Change: Reviving Governance and Citizenship in the Middle East,” a Century International project supported by the Carnegie Corporation of New York and the Open Society Foundations.

Header Image: A woman cries during the funerals for former Hezbollah leaders Hassan Nasrallah and Hashem Safieddine at the Sports City Stadium on February 23 in Beirut. Tens of thousands of people gathered in Beirut to attend the funerals, nearly five months after the leaders were killed in an Israeli airstrike on a southern suburb of the Lebanese capital. Source: Daniel Carde/Getty Images

Notes

- Alissa J. Rubin, “New Fear Divides Lebanon: Where People Flee, Bombs Follow,” New York Times, November 15, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/11/15/world/middleeast/lebanon-refugees-israel-bombing.html.

- “Lebanon: Flash Update #53—Escalation of Hostilities in Lebanon, as of 02 January 2025,” UN Office for the Coorination of Humanitarian Affairs, January 2, 2025, https://www.unocha.org/publications/report/lebanon/lebanon-flash-update-53-escalation-hostilities-lebanon-02-january-2025.

- “Naim Qassem Says Cease-Fire with Israel ‘A Great Victory That Surpasses That of July 2006’: Day 420 of the Gaza War,” L’Orient Today, November 28, 2024, https://today.lorientlejour.com/article/1437456/israeli-army-tells-residents-of-dozens-of-southern-lebanese-border-villages-not-to-return-home-day-420-of-the-gaza-war.html.

- Hussein Shaaban, “UNIFIL Urges Timely Israeli Pullout from South Lebanon Under Month-Old Truce Deal,” Reuters, December 26, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/unifil-urges-timely-israeli-pullout-south-lebanon-under-month-old-truce-deal-2024-12-26/.

- “Geography of Occupation: ‘The Monster Is Swallowing Our Villages,’” (in Arabic), The Legal Agenda, May 7, 2025, https://legal-agenda.com/جغرافيا-الاحتلال-الغول-يبتلع-قرانا/.

- “Ceasefire in Lebanon Shaky, Huge Gap Between Promises and Reality: Analysis,” uploaded to YouTube by Al Jazeera English (@aljazeeraenglish) on November 27, 2024, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1T29Vq8LCE8&ab_channel=AlJazeeraEnglish.

- Simona Foltyn and Ahmad Baydoun, “Lebanese Villagers Blocked from Returning Home as Israeli Forces Remain in Area,” PBS, February 9, 2025, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/lebanese-villagers-blocked-from-returning-home-as-israeli-forces-remain-in-area.

- “Israel Must Stop Killing Civilians Returning to Their Homes in South Lebanon: Un Experts,” UN Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights, press release, February 13, 2025, https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2025/02/israel-must-stop-killing-civilians-returning-their-homes-south-lebanon-un.

- Hussein Shaaban, “Aggression on Saturday, March 22: The South Remains Steadfast in Its Mourning Processions, While the State Does Not Attend Condolences” (in Arabic), Legal Agenda, March 26, 2025, https://legal-agenda.com/عدوان-السبت-الجنوب-صامد-بِمآتمه-والدو/.

- Matt Murphy and Joe Tidy, “What We Know About the Hezbollah Device Explosions,” BBC, September 19, 2024, https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cz04m913m49o.

- Haider, Bashar. “Victory and the Burden of Prevailing.” Nidaa Al-Watan, December 2, 2024. https://www.nidaalwatan.com/article/294838-النصر-وعبء-الغلبة; see also Raji Mahdi, “On Hezbollah and the Iranian Defeat” (in Arabic), Chroum, January 3, 2025, https://chroum.com/article/حول-حزب-الله-والهزيمة-الإيرانية.

- On reconstruction efforts organized by community groups and individuals directly after the ceasefire, see Jennifer Holleis and Sara Hteit, “Ceasefire in Lebanon: Civil Society Ramps Up Reconstruction Plans,” Deutsche Welle, November 29, 2024, https://www.dw.com/en/ceasefire-in-lebanon-civil-society-ramps-up-reconstruction-plans/a-70919839.

- On recent developments on how these compensations are being distributed on the ground and additional testimonies from residents, see Sally Abou Aljoud, “Lebanese Whose Homes Were Destroyed in the War Want to Rebuild. Many Face a Long Wait,” AP News, November 28, 2024, https://apnews.com/article/lebanon-israel-hezbollah-ceasefire-reconstruction-dea56cbb5e5615b4973fcdb2d7b53de2; see also Malaika Kanaaneh Tapper and Richard Saleme, “How Hizbollah is Using Cash and WhatsApp Groups to Shore Up Power,” Financial Times, February 11, 2025. https://www.ft.com/content/6f67322f-bd89-4e50-873c-b8ed576cbd4d.

- Ahmed Sultan, “The Mole Among the Men of the Sayyed: What Happened to Hezbollah in This War?” (in Arabic), Chroum, September 26, 2024, https://chroum.com/article/الخلد-وسط-رجال-السيد-ماذا-جرى-لحزب-الله-في-هذه-الحرب.

- According to Mohammad Chamseddine, head of research at Information International, Israel has completely destroyed 260 buildings and partially damaged 180 others, primarily in Haret Hreik, Laylaki, Jamous, Ghobeiri, and Chiyah. See Naghamn Rabih, “We’d Rather Die at Home: Displaced Lebanese Return to Beirut’s Southern Suburbs,” L’Orient Today, November 20, 2024, https://today.lorientlejour.com/article/1436280/wed-rather-die-at-home-displaced-lebanese-return-to-beiruts-southern-suburbs.html.

- Enas Sherri, “The Ordeal of Sheltering the Displaced (2): Between Official Administration and Actual Management,” The Legal Agenda, December 21, 2024, https://legal-agenda.com/محنة-إيواء-النازحين-2-بين-الإدارة-الرس/.

- Ibid.

- Bassem Mroue, Abby Sewell, and Sally Abou Aljoud, “Masses of Mourners Attend the Funeral of Hezbollah Leader Nasrallah, 5 Months After His Killing,” AP News, February 23, 2025, https://apnews.com/article/lebanon-israel-hezbollah-funeral-nasrallah-hashem-safieddine-5b698c1d403887135e35b20c4cb22413.