As public and nonprofit colleges have sought to expand their online course offerings, a major industry has developed to help them with that task. These private, for-profit developers—including divisions of big publishers, like Wiley and Pearson, and firms like 2U, Academic Partnerships, and Bisk—are known as online program managers (OPMs). They operate on a contract basis, and on terms that endow them with enormous, and, at times, comprehensive control over the services offered in the contracting college’s name. There are downsides to handing over responsibilities to external, for-profit operators—downsides that make the convenience schools receive in return seem a bad bargain indeed.

Two years ago, The Century Foundation did a major study of partnerships between private OPMs and public universities, drawing on contracts from every state in the country.1 We learned that these partnerships are as bad as many had suspected, if not worse: in return for some superficial convenience, public universities in every corner of the United States had been putting their for-profit contractors in the driver’s seat in nearly every respect, including financial considerations. More often than not, more than half of the programs’ tuition revenue goes straight to the contractors.

This year, TCF followed up on that research, looking at an entirely new tranche of OPM–university contracts, and our findings reflect those trends from 2017, deepening this already deeply unsettling picture. In this report, we share those findings, but we don’t stop there: through a typology of the actors to be wary of and an outline of five contracting red flags to avoid, we also provide schools with the know-how they need to start fighting back, and what to do instead. Along the way, we interweave examples from this year’s contract analysis, to demonstrate how theory can be put into practice to allow for safer contracting.

If schools act quickly and effectively, they can make a lot of progress in curtailing this crisis, protecting their students and themselves in the process. Our hope is that this action-focused report will assist schools and those who care about them to jumpstart a paradigm shift in how online education in the United States is done.

The OPM Landscape Today, Revealed: Lessons from Our New Data

Bad deals made with for-profit actors are nothing new in higher education;2 and since 2017, The Century Foundation has been monitoring this aspect of the industry, using state FOIA laws to acquire the contracts between public higher education institutions and online program managers. In that first year of our research, TCF requested contracts related to online courses and programs from the flagship public institution and at least one community college in each state, as well as a set of randomly selected schools around the country, and analyzed the data we received.3 From that analysis, we learned:

- OPMs are largely private, for-profit enterprises.

- Programs where OPMs control the majority of course development and operations in exchange for a share of tuition revenue expose students to the same risks involved with enrolling in a for-profit college, but with even less protection than those students receive, since an online program is run under the guise of a public institution, wherein public interest is assumed to be the chief priority.

- The most problematic aspects of public university–private OPM contracts are tuition-sharing schemes; the lack of transparency afforded students and the public; and the exchange of student and prospective student information and data.

Our analysis revealed that, by and large, contracted online programs in higher education are wolves in sheep’s clothing: predatory for-profit actors masquerading as some of the nation’s most trustworthy public universities.

This year, to expand our data pool and our analysis, we requested contracts from public institutions with a large number of students enrolled online.4 The new data reinforced the trends we found in our 2017 analysis: for-profit OPMs exercise far more control over online programs than do the schools themselves, to the detriment of both students and the hosting institutions.

As of August 2019, our new batch of public records requests has garnered contracts that outline arrangements between seventy-nine public colleges and universities and third-party providers. The trends put forth below are in regards to these contracts alone, and are not necessarily representative of the nationwide status of online degree programs, nor of all forms of contracting in higher education.

Types of Partnerships

One important result of our research is that we continue to see two distinct types of university–OPM partnerships: those in which the school hands over tuition revenue to the third party and those in which the school pays a flat rate for services. Though they are undetectable and indistinguishable from the perspective of students and consumers, the differences between these types have important implications on cost and quality for both institutions and students. Differentiating them will help institutions to avoid the harms of many such arrangements in the future.

One of the more prevalent forms of partnership is a tuition-sharing agreement. Companies like 2U, Academic Partnerships, Wiley, and Pearson, which have been prominent in the OPM space for as long as a decade, usually contract with schools using this type.5 In such an arrangement, a portion of the tuition is handed over to the OPM in exchange for a bundle of services: the amount the OPM receives typically runs anywhere from 40 percent to 65 percent, with some contracts going as high as 80 percent. These partnerships tend to involve very long contracts, ranging from six to ten years, and sometimes have very strict exiting terms and automatic contract renewals.

Entities that consider themselves providers of Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) have not traditionally operated in the same vein as OPMs, but schools have increasingly started working with them to run certain courses or entire programs. Run by companies like Ed2Go, Coursera, and Edmentum, they are referred to as “massive” and “open” because they offer their courses freely to the public, at least to some extent. Offered by itself, a MOOC can be an efficient, low-cost option for a student to advance in one specific skill-set. Coursera, for example, provides many of its courses to the public completely free. However, it rapidly becomes problematic when a MOOC is offered and marketed as a public institution’s course, yet created and staffed entirely by the MOOC provider. Because a MOOC is an online course in and of itself, the companies often provide the course content as well as the instructor. MOOCs also tend to take a substantial portion of the tuition revenues, with a typical cut spanning 50 percent to 80 percent.

While MOOCs may not consider themselves to be OPMs as traditionally defined, they frequently contract and behave more or less identically to how OPMs like 2U and Wiley contract and behave. Accordingly, our trend analysis includes OPMs and such OPM-adjacent entities, many of whom, furthermore, have evolved overtime to become partnered, merged, or acquired by one another.6

A second form of partnership is the fee-for-service model. Companies such as iDesignEDU, Noodle Partners, and ExtensionEngine offer specific services for a fixed price. Specific services in this case could be anything from course development to faculty training to marketing. The important feature of this type of partnership is that a contract covers one service alone in exchange for a single lump sum. In other words, the payment is not directly linked to tuition—or to enrollment numbers.

A separate entity that exists near the fee-for-service model is the learning management system (LMS) provider. An LMS is a software application that schools can develop themselves or contract out to host various activities, like storing assignments, managing grades, and so on. Since LMS providers, like Blackboard and Instructure for example, are large tech companies that contract their services to schools, and some OPMs simultaneously offer LMSs, it is important to consider the nature of these partnerships under the realm of public–private education contracting. However, this report primarily focuses on partnerships that have greater influence over a school’s academics, admissions, and, consequently mission.

Our New Data, and What They Tell Us

Keeping our analysis within the bounds of the typology outlined above,7 our findings, while reinforcing those TCF made two years ago, are nonetheless striking and distressing. Here, we present a summary of the types of partnerships and characteristics found within the relevant contracts, and provide the key takeaways we see in the data and trends. Of the contracts pertaining to the management of online programs, partnerships where the school hands over a portion of its tuition revenue are more problematic than are fee-for-service arrangements. Detailed examples outlining why this is and how to avoid these problems follow throughout the second half of the report.

As of August 2019, we received seventy-nine contracts, and of these, forty-one are directly relevant to the management of online courses. These forty-one do not include contracts that only address access to software like learning management systems. Of the relevant contracts, over half (53 percent) entitle the provider to a share of the school’s tuition. Typical arrangements involve the college or university splitting about half of its revenue with the third party, though it can vary by program and year. Such is the case, for example, in a ten-year contract between the University of North Dakota and Pearson: in the early years of the agreement, UND will hand over 62 percent of its tuition revenue which tapers down to 54 percent by the tenth year. At the lowest end of these revenue-share agreements is a five-year deal between the University of Arizona and for-profit OPM All Campus: the university gives 35 percent of its tuition revenue to All Campus. The highest amount of tuition handed over from institution to private third-party provider is 80 percent, and these are found between colleges and private career training bootcamp providers Ed2Go and The Learning House. In these arrangements, the contractor usually fully develops and runs the program, including by providing instructors.

Forty-one percent of relevant contracts task the provider with recruiting on the school’s behalf. Some OPMs contract with different institutions for similar degree programs, which likely helps these third-party companies more easily develop and use recruiting materials. For example, the for-profit OPM Academic Partnerships manages recruiting for the same types of programs at seven institutions in our contract set:

- Boise State University

- Eastern Michigan University

- Emporia State University

- Louisiana State University

- Louisiana State University Shreveport

- Southeastern Oklahoma State University

- University of West Florida

Academic Partnerships manages and recruits for online business degrees offered by six of the above institutions, and does the same for four of the institutions’ online education degrees, underscoring the potential for third-party online program managers to efficiently provide certain services—whether those efficiencies are passed on to students or not.

One of the primary reasons institutions cite for seeking outside help in developing online programs is a lack of internal capacity for developing or transferring courses into a format conducive to online study. It was not surprising, then, that in 68 percent of contracts, the third-party provider develops the course and/or the program. In fewer cases, just 32 percent of contracts, the third party also provides instruction. These tend to be at programs marketed as short-term, certificate, or “boot camp” in nature. Our contract set includes arrangements where companies like Ed2Go, The Learning House, Trilogy, and WozU design the program from top to bottom, including instruction, under the brand name of a university.

Of contracts with clear terms concerning the length of the agreement, 56 percent last for five years or more. Six of these contracts last between seven and ten years and involve the OPMs Academic Partnerships, Everspring, and Pearson, companies that frequently operate using a revenue-share model. This is noteworthy because the longer a school’s contract, the more entrenched in the school the OPM becomes, even more so if the OPM is running multiple aspects of the program. With the incentive to generate as much profit as possible, some of these for-profit third parties make it nearly impossible to get out of an agreement. Over a quarter (27 percent) of the total contracts reviewed lock in schools with strict exiting terms. These terms include things like requiring a years-in-advance termination notice, automatic renewals, and clauses prohibiting schools from contracting with other companies for similar services after termination. We only came across these terms in revenue-share agreements. Furthermore, some contracts appear to give the third party ability to profit off of student data, and 32 percent have vague terms or say nothing about data usage at all, which leaves it unclear who really has authority over students’ information.

In sum, the data, patterns, and trends we’ve culled from this batch of contracts not only underscore how much control for-profit companies have over these public online programs, but also illuminate how much they’re profiting off that control, as well as many of the contractually binding methods that they employ to acquire and maintain control.

In sum, the data, patterns, and trends we’ve culled from this batch of contracts not only underscore how much control for-profit companies have over these public online programs, but also illuminate how much they’re profiting off that control, as well as many of the contractually binding methods that they employ to acquire and maintain control. The picture is a troubling one indeed; and we’ll now turn to what can, and should, be done in response.

Fighting Back: Five Don’ts for Colleges and Universities

We’ve now made public the full set of the contracts we’ve used in our analyses, those acquired this year as well as those acquired in 2017: you can browse and read them here. Readers will find that they reveal how frequently colleges have been taken for a ride by OPM companies, forfeiting too much control and at too high a price. The results have been such that, essentially, OPM companies are operating for-profit colleges under the brand names of public universities.

College administrators and other stakeholders will be pleased to learn, though, that such predatory arrangements are far from a foregone conclusion. There’s much that colleges can do to protect themselves and their students. Here we offer five key “don’ts” for colleges, based on examples from our contract analysis and the hard lessons some universities have learned in expanding their online offerings. We also include examples of better approaches. These best-practice tips are calibrated to protect institutions from all of the OPM and OPM-adjacent permutations discussed above, making it much simpler to respond to the varying forms that these predatory actors can take.

1. Don’t Buy Bundled Services.

In 2009, the University of Southern California (USC) contracted with 2U to capitalize on the school’s well-regarded School of Social Work by creating and developing an online master’s degree program in social work. The program was launched and expanded very quickly: it quadrupled in size between 2010 and 2016. Under the contract, 2U would receive 60 percent of the program’s tuition revenue for managing much of the enterprise, including course development, marketing, and recruiting. This bundling together of services into a near-complete package, while still keeping nearly half the tuition revenue, seemed like a very convenient way to expand profits without having to build any additional infrastructure or hire any new full-time staff. But 2U is a for-profit enterprise, and with the for-profit contractor responsible for recruiting and getting a large cut of every student’s tuition, their incentive to find and enroll students was very high. Since USC had given over so much control to 2U, it had little control over how the program recruited, or who it enrolled: as revealed by the Los Angeles Times earlier this year, the online social work program admitted students that it was not prepared to provide with a quality education, charging them more than $100,000 for their degree in the process. All the while, USC reportedly lost money on the program, because so much of the tuition went to 2U.8

Now the program’s reputation, as well as that of the USC School of Social Work, are sullied. And worse, TCF analysis reveals that the online program’s graduates are struggling not simply with large student loan debts, but astronomical ones—within the top ten nationwide in terms of individual debt burdens. They stand out from the pack in this respect as the only ones whose debts have been incurred while in neither medical school nor a for-profit school. Furthermore, these graduates have the largest combined loan debt of any graduate program, and of any type, in the country.9

Table 1

| Top Ten Total Combined Student Loan Debts by Major, 2015–2016 and 2016–2017 Cohorts | |||

| School | Type of Control | Major | Federal Debt of Graduates |

| University of Phoenix | For-Profit | Bachelor’s Degree in Business Administration, Management | $412,543,398 |

| University of Southern California | Nonprofit | Master’s Degree in Social Work | $277,547,010 |

| Walden University | For-Profit | Master’s Degree in Registered Nursing | $223,885,332 |

| Chamberlain University | For-Profit | Bachelor’s Degree in Registered Nursing | $198,305,626 |

| University of Phoenix | For-Profit | Bachelor’s Degree in Health Administrative Services | $193,995,432 |

| Strayer University | For-Profit | Master’s in Business Administration and Operations | $193,584,220 |

| Lake Erie College of Osteopathic Medicine | Nonprofit | Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine/Osteopathy | $188,697,600 |

| University of Phoenix | For-Profit | Master’s in Business Administration and Operations | $173,178,808 |

| University of Phoenix | For-Profit | Bachelor’s Degree in Behavioral Sciences | $169,515,200 |

| Palmer College of Chiropractic | Nonprofit | Doctor of Chiropractic | $159,569,400 |

| Source: TCF analysis of data from U.S. Department of Education, “College Scorecard Data: Preliminary Load Debt Data by Field of Study.” Data available at https://collegescorecard.ed.gov/data/preliminary/ | |||

Tuition-share agreements like this one, while not always as massively catastrophic as the USC–2U partnership, aren’t hard to find in today’s online education landscape, as we found that over half of the contracts TCF received this year are bundled-service, tuition-sharing schemes.

A straightforward way to avoid a fate like USC’s is to turn down bundled services contracts altogether. Institutions should instead contract for the specific services they need, when they need them, as discrete units, and pay a fixed price for them. For example, the University of Nebraska contracted with iDesignEDU for development of an online medical ethics course. Online course development in this contract brings together iDesignEDU’s instructional designers with the University of Nebraska’s faculty to create new or revamp existing online classes. The university pays the company a set price of $35,000 for each course that is developed and $8,500 for each course that is redesigned. We cannot speak to the prevalence of such fee-for-service contracting in the realm of online program management nationwide, as our sample included just a few examples (with the exception of sixteen contracts between institutions and learning management system providers like Blackboard); it’s clear, however, how much less risk is involved, and how much is gained, from working with them instead.

Because our sample of contracts lacks a larger set of fee-for-service arrangements, it is not possible to speak definitively about pricing for particular services. Institutions could benefit from sharing their third-party contracting information with each other to increase understanding of fair pricing of services, as well as to increase their awareness of what they may or may not have the capacity to develop or provide in-house. Many institutions enter bundled contracts because of pressure to launch online programs quickly, and university decision makers aren’t always the ones aware of their own institutions’ ability to take on some or all of the work involved in doing so.

That being said, a fee-for-service model like the University of Nebraska’s contract with iDesignEDU allows for more transparency around services you’re electing and the price you’re willing to pay for them. By taking the wheel on nearly every aspect of program management, bundled OPMs function as a black box and leave the school unable to learn the processes for itself. Fee-for-service OPMs, in contrast, are frequently designed to work with the school in a way that enables the school to eventually offer such services on its own. This model leaves greater room for a school to maintain control over its governance, revenue, and mission.

Fee-for-service providers, at least in their advertising, offer what colleges should be looking for:

“We help our clients build internal knowledge and capacity so they can sustain and grow their business on their own.” –ExtensionEngine10

“Fee-for-service pricing enables us to leave intellectual property rights, control, and tuition revenue where they belong – with the university.” –iDesignEDU11

While advertising alone is far from a trustworthy indicator of a company’s true intentions, there is a notably stronger emphasis on enrollment or revenue growth in the marketing of bundled-service, tuition-share models by comparison:

“Helping universities grow and students succeed.”–Academic Partnerships12

“Growth: Strengthen your financial outlook by creating in-demand and highly sought after degree programs.”–Pearson13

As accredited institutions, universities are gatekeepers to federal student aid dollars, a large portion of which are handed over when an OPM is involved. Universities have the power to shop around for companies with values or priorities that reflect theirs. A school that does not want its programs to develop the predatory behaviors that often emerge at for-profit colleges should insist on contracts that prohibit changes to pricing, recruiting, or admissions standards based on enrollment actuals or projections, or on the fiscal performance of the program. Contracting for short-term, specific, discrete services instead of for a long-term, all-in-one program manager is an excellent way to curtail a college’s inadvertent complicity in such behaviors.

2. Don’t Bypass Your Own Faculty.

At the University of North Dakota (UND), if members of the cybersecurity faculty decide students would be better served by changing the curriculum or offering a different track or certification, they would have very little chance of making those changes a reality. This is because UND contracted with Pearson in 2018 to manage an online program in cybersecurity, as well as its online programs in nursing and accounting—contracts that wrest most educational control from the professors and instructors who have been hired to teach those subjects. The contract prevents the university from making changes to curricula or concentrations without first appealing to Pearson. Pearson then evaluates the effect of the proposed changes on enrollment. Student needs and faculty knowledge about professional practice are superseded by the enrollment and revenue priorities of the OPM.

To prevent such a predicament from developing, university contracts with OPMs should make it clear that the university has the power to determine how the online program is used. Universities are finding, for example, that their students living on campus do better when they have the option of taking some classes online. Clear terms that delineate university control over the use of programs that are developed as a result of the partnership would give universities the power to merge online and ground campus offerings if and when doing so is in the interest of student success.

Some university–OPM contracts include a steering committee devoted to the degree program being managed. Too frequently, these provisions give too much power to the contractor. A contract between Kent State University and Everspring, for instance, creates a steering committee of Everspring and university representatives that has “decision-making authority to jointly administer the Programs.” Additionally, the contract specifies that “all actions of the Steering Committee required under this Agreement will require the mutual consent of the Parties.” Other contracts involving steering committees require equal representation from each party, and give the OPM an equal vote on all matters presented before the steering committee.14 This is backwards: an interest in quality education dictates that the OPM should not have an equal say, but a smaller say in steering the degree program. Their own bottom line must always be harnessed to the quality of education offered, the fiscal safety of the program’s students, and the contracting client’s reputation.

We found a better approach to program governance in a contract between Pearson and the University of Illinois at Chicago. In this arrangement, the university-based academic director is responsible for decisions regarding size and standards of all online programs. This demonstrates that schools can successfully negotiate for terms that ensure the school’s academic leadership, faculty, and students steer the direction of programs.

Contractors working inside a university to develop online programs certainly need to work closely with university officials. But ultimately the decisions about how to proceed should be made by university officials in consultation with the relevant faculty members.

3. Don’t Sign Lengthy, Unbreakable Contracts.

Too many colleges have signed OPM contracts so restrictive that leaving the partnership is next to impossible. Boise State University, for example, must give Academic Partnerships (AP), its contracted OPM, two years’ notice to keep its contract from auto-renewing for another three years. What’s more, if the agreement reaches its full five-year term and Boise State manages to end the contract, the school must continue paying Academic Partnerships for each student it secured that is still taking online courses at the school. And perhaps worst of all, if Boise State terminates the agreement early, it can’t work with any other similar provider for the same programs until after what would have been the fifth anniversary of the contract. This arrangement leaves Boise State with no recovery options other than completely abandoning a program and its students if it wants to alter who or how the program is managed.

Eastern Michigan University, Emporia State University, and Southeastern Oklahoma State University have each contracted with AP as well, and all three have the same post-term payment provisions in their agreements. Further, these institutions’ contracts with Academic Partnerships have a “right of first offer” clause, which states that if the school is considering using a similar provider for programs that were not initially included in its agreement with Academic Partnerships, the school must first offer these programs to AP.

Nearly all contracts reviewed between institutions and AP had term lengths of seven to ten years, and would automatically renew unless terminated in advance. The schools’ termination powers were very weak in many of the contracts, sticking them with limited options and timeframes in which to terminate the agreement without incurring pricey penalties. Several contracts automatically renew for two- to three-year periods at a time, and don’t allow for a school to terminate without giving one to two years’ notice. For instance, Emporia State University, having signed a ten-year contract, can’t initiate a termination of the agreement without incurring enormous penalties until its eighth year. Louisiana State University is the only school we have found whose contract with Academic Partnerships allows it to terminate the agreement for any reason with thirty days’ notice and without penalty. In fact, Louisiana State University officials informed us that the university ended its contract with Academic Partnerships in October 2018, and opted to begin managing online programs in-house.

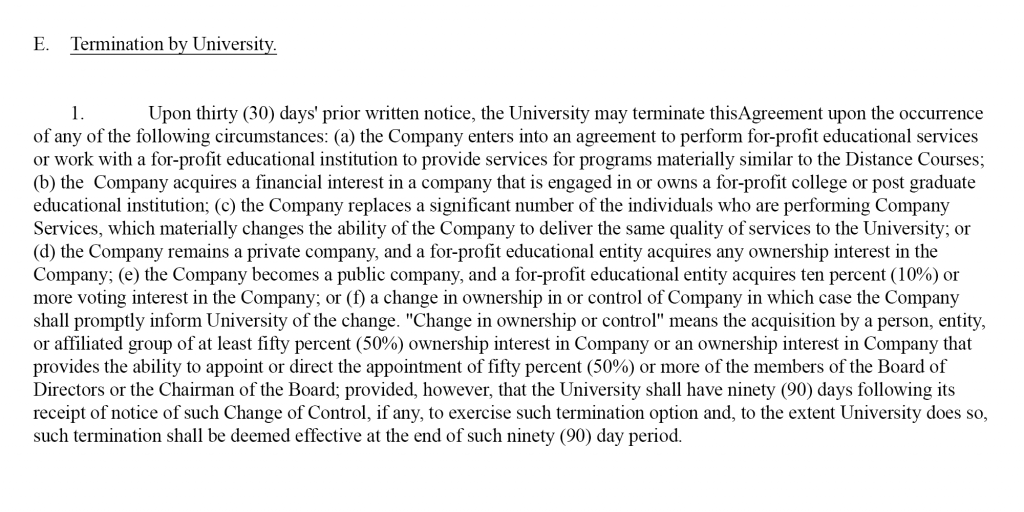

Many of the big OPM providers contract in this way, and our research reveals that AP is far from the only OPM to have left their clients with the short end of the stick. The University of Florida, for example, must have had such a bad experience with their eleven-year contract with Pearson that they ended it abruptly in 2015, less than two years after it began.15 Since then, the University of Florida has contracted with AP and Apollidon instead, and in their contracts with these two OPMs, the school retains the right to terminate the contract if the company offers similar services to for-profit colleges or acquires a financial interest in a for-profit college. This is indicated in an identical clause found in both contracts (see image below). The university can terminate the agreements with thirty days’ notice for circumstances including if the company:

- enters into an agreement to work with a for-profit educational institution to provide similar services;

- acquires a financial interest in a company that is engaged in or owns a for-profit college;

- replaces a significant number of the individuals who are performing the company services;

- a for-profit entity acquires an ownership interest in the company, without the company first having converted out of their private status; and/or

- becomes a public company and a for-profit entity acquires a ten percent or more voting interest in the company.

Figure 1

If the goal is to allow universities to be innovative, adaptive, and responsive, then short-term contracts are ideal. Institutions also need to be able to reasonably terminate contracts and to shop around for new providers. The University of Florida’s decision to directly build their values into the contract by penalizing even peripheral predatory behavior is an excellent model in both spirit and letter.

4. Don’t “Share” Your Tuition Revenue.

We’re glad to see that, as Inside Higher Ed reported last month, universities shopping for an OPM with whom to contract have become more skeptical about large, lengthy tuition-sharing contracts for bundled services.16 One reason, no doubt, is that word has spread about bad experiences and the resulting negative media attention.17 Exposed to the light of public scrutiny, it simply does not sit well with people that a public or nonprofit would be so cavalier with students’ tuition that they turn over half or more of it to an outside for-profit company, all while giving them free rein over managing their degree programs. At minimum, deals like these seem cynical, and at worst sleazy, or downright unethical. In general, they’ve underscored a growing sense that online education’s initial promise as a democratizing force has turned out to be just another way for the profit motive to commandeer and corrupt our public educational institutions’ programs and practices.18

Table 2

| A Sample of Revenue-Share Agreements | |||

| Institution | Provider | Provider’s Share of Revenue | Scope of Services |

| Southeastern Oklahoma State University | Academic Partnerships | 50% | Marketing, recruitment, program development, academic support, student support, application support |

| University of West Florida | The Learning House | 80% | Course and curriculum development, online infrastructure development and management, learning management system, 24/7 technology support, marketing, recruitment and enrollment, employer network |

| University of North Dakota | Pearson Embanet | 54%-62%, depending on the term year | Development of e-learning program, course design and development, marketing, recruitment, student support, help desk, business administration, program accounting, program and business funding |

| Eastern Kentucky University | Pearson Embanet | 40%-45%, depending on enrollment levels | marketing, recruitment, management and retention |

| Source: TCF analysis of acquired contracts, available here. | |||

Consider the contract between UCLA and Trilogy19 to run a coding bootcamp through the university’s extension school.20 Under the contract, UCLA must set the tuition price as high as the market will bear. And to enforce that provision, Trilogy also has the right to veto the price set by UCLA.21 The very purpose of a public college’s extension school—to make high-quality continuing education affordable and available to as many people as possible—is directly undercut by such a contract. No wonder observers and consumers are starting to protest.

Some of the market’s turn away from tuition-sharing deals may involve legal considerations as well, in addition to the above-discussed concerns about ethics, appearances, and good business practices. Foremost, we must remember that the core legal requirement—which undergird and bolster public expectations—of nonprofit entities is that no profits are extracted by any private party: money earned above costs is recycled back into the organization, to be used in the pursuit of its educational or charitable purpose. Shoveling a large share of revenue to a for-profit contractor could very well bring a university’s nonprofit or public status into question.22

A second legal issue arises when contractors are involved in recruiting students. The Higher Education Act prohibits institutions that use federal financial aid from making any “incentive payment based directly or indirectly on success in securing enrollments or financial aid to any persons or entities engaged in any student recruiting.”23 In other words, a college cannot treat the admissions process as a sales operation ginned up by paying commissions to the sales force. While guidance from the U.S. Department of Education says that bundled service contracts don’t cross that line, the validity of that guidance has not been legally tested. At some point, a student or competing college that is harmed by one of these deals will likely take that issue to court, dragging in both the school and the contractor.

When colleges need outside help, rather than hand over a portion of tuition revenue for an expansive suite of services, they should contract for the services needed and pay for them directly. This is the wiser choice for many reasons, not the least of which being that payment is unlinked from tuition revenue and enrollment levels. Tuition revenue-linked payment schemes create incentives for predatory behavior and mask the real work, and cost, of providing online education opportunities. Fee-for-service partnerships make it very clear who is doing what and for what amount of money in return.

Table 3

| A Sample of Fee-for-Service Agreements | |||

| Institution | Proiver | Price | Service(s) |

| University of Nebraska Online Worldwide | InsideTrack | $48,150 | Internal and competitive analysis |

| University of Nebraska Online Worldwide | iDesignEDU | $35,000 | Course design and development |

| Black Hawk College | Instructure | $495,370 | Learning management system |

| Chadron State College | Longsight | $55,000 | Learning management system |

| University of North Dakota | Thruline Marketing | $175,000 | Marketing |

| Source: TCF analysis of acquired contracts, available here. | |||

The University of Florida’s example offers a possible middle ground. In its contracts with AP and Apollidon (discussed above), and now in all of its contracts with third-party providers, the school has a standard set of clauses regarding pricing that is particularly strong and in favor of the institution and students.24 These clauses include the following: that “The University will not approve unsupported price increases that merely increase the gross profitability of the Company at the expense of the University.” The University of Florida’s offices of general counsel and the provost developed these standards, and ensure that all contracts the school signs take them fully into account.

In the current landscape of university–OPM contracts, most agreements either include a vague statement like this one between Southeastern Oklahoma State University and Academic Partnerships: “The University will assure that its total tuition and fees for the Online Programs is no more than the campus-based tuition and fees,” or they include no specific treatment of the topic at all. Schools should insist on a clear clause that outlines its autonomy over tuition decisions. The consideration of tuition price—what the rate is, how it is set, and who has control over those decisions—in the management of online programs is important, especially if schools are still considering handing their tuition revenue, in any amount or percentage, over to for-profit service providers. The absence of definitive language that gives the school the power to set its own tuition rates opens the institution, students, and prospective students up to predatory behavior on the part of the third-party company. Tuition-sharing partnerships are more likely to have problematic pricing and problematic recruiting and enrollment practices.

5. Don’t Facilitate Aggressive Recruiting.

On average, the universities from whom we’ve acquired contracts share half of their tuition dollars with the partnering OPM, and when that OPM is a for-profit company, as most are, and is also tasked with recruiting, it is incentivized to get as many enrollments as possible. This scenario leads to the same predatory and aggressive recruiting tactics long used by for-profit colleges, but this time under the very different guise of a nonprofit or public university.25

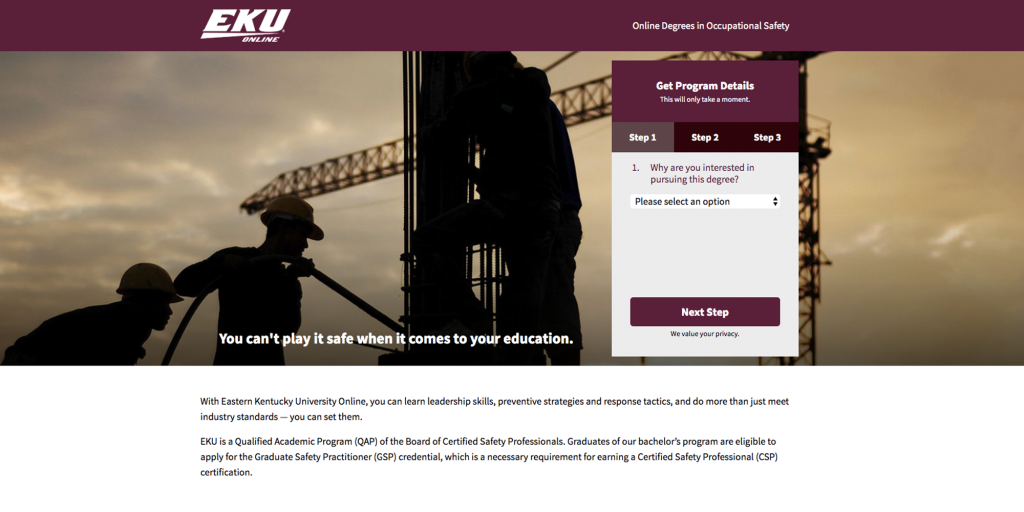

At most reputable colleges, a prospective student can go online to get information about a program’s cost, schedule, faculty, and admissions policies. Try to get information about Eastern Kentucky University’s online bachelor’s degree in occupational safety, however, and you are out of luck—unless you are willing to respond to a questionnaire that requires you to hand over your phone number and email.

Figure 2

Once a student plugs in their contact information, they can expect to receive multiple text messages and phone calls from the OPM’s employees (in this case Pearson staff), acting as representatives of the university. Some contracts require a minimum number of attempts the company must make to reach the student: The Learning House (a Wiley subsidiary) specifies that its “contact agents” must make at least thirteen attempts to contact every new prospective University of West Florida student—for ten days in a row. Companies are also put in the driver’s seat in terms of what representatives say to prospects. The contract between Pearson and Eastern Kentucky reads, “The Company shall be responsible for all activities related to the creation of scripts that may be used in discussions with, and management of, telephonic contact with prospective students.” Not only is the OPM blitzing students, even harassing them, with communications: what it communicates is entirely up to Pearson.

Pearson also manages multiple online programs for the University of North Dakota. In their master services agreement, UND hands over to Pearson ownership of the data files containing the names and contact information of prospects who inquire about the UND programs. That means that Pearson can market other programs and products to those targets. More worrisome, it also means that Pearson can sell those personal details to other colleges or to other marketers.

There are smarter, safer ways to contract for these services. In contrast with UND and Eastern Kentucky University, the University of Nebraska, in its contract with Thruline for its online business and health sciences programs, limits the OPM’s activities strictly to marketing, and bases revenue sharing not on any proportion of tuition but instead on the number of inquiries from people qualified to enroll. The university also maintains firmer control over the content and conduct of recruiting and follow-up steps than do Eastern Kentucky and UND, thus protecting its own brand and reputation.

Universities should maintain control over recruiting, admissions, and enrollment decisions. Any recruitment leads generated by a third-party recruiter should become the sole property of the university.

Looking Ahead—and Banding Together

If the best practices outlined in this report are followed, our public universities can feel certain of heading off many of the harms and ills that we’ve found in the partnerships we’ve analyzed over the last two years. To close, we suggest one more best practice: schools should work together. Peer institutions should share contracts, and the results of partnerships, with each other, and also leverage university systems and/or consortiums to bring transparency to the OPM contracting process permanently.

Editorial note: This report was updated to reflect the current status of Louisana State University’s relationship with Academic Partnerships.

Appendix

Contracts obtained from public institutions are available for download here. We have also prepared and included a table listing all of these contracts, offering at-a-glance evaluative information on a number of criteria. As we receive additional contracts, the list will be updated. For each university–third-party-provider contract, we have indicated with a “Y” in the relevant table cell if the named characteristic was obviously present. Empty cells do not necessarily mean such characteristics were absent: some contracts lack mention of some characteristics, and in some cases some characteristics are irrelevant for the scope of the contracted services. We have also left cells empty in cases where a contract is less clear in its treatment of the characteristic(s) of interest.

College Contracts for Online Services Reviewed

ADEC and Apollidon

Alabama State University and Kaplan

Albany State University and LearningHouse

Arizona State University and Pearson

Arizona State University and Coursera

Auburn University and Everspring

Ball State University and Blackboard

Black Hawk College and Edmentum

Black Hawk College and Ed2Go

Black Hawk College and Pearson

Black Hawk College and McGraw-Hill Education

Black Hawk College and Tutor.com

Black Hawk College and RedShelf

Black Hawk College and Instructure

Blue Mountain Community College and Blackboard

Blue Mountain Community College and Canvas

Blue Mountain Community College and TPC

Boise State University and AP

Boise State University and HBX

Boise State University and Instructional Connections

Central New Mexico Community College and Blackboard

Central Texas College and Blackboard

Chadron State College and Longsight

Cleveland State University and Blackboard

Cochise College and Ed2Go

College System of Tennessee and Coursera

College System of Tennessee and D2L

Dakota State University and D2L

Eastern Kentucky University and Pearson Embanet

Eastern Kentucky University and Blackboard

Eastern Kentucky University and Learning Objects

Eastern Kentucky University and Smartthinking

Eastern Michigan University and AP

Eastern Michigan University and Instructure

Eastern New Mexico University and Blackboard

Emporia State University and Instructional Connections

Emporia State University and AP

Florida State University and Keypath

Framingham State University and Blackboard

Georgia College and State University and Ed2Go

Grand Rapids Community College and Blackboard

Grand Rapids Community College and Ed2Go

Highland Community College and Ed2Go

Idaho State Board of Education and Blackboard

Indiana University and Unizin

Institute for American Indian Arts and Blackboard

Jacksonville State University and Blackboard

Jacksonville State University and Instructure

Johnson County Community College

Kent State University and Everspring

Kentucky Community and Technical College System and Blackboard

Kentucky Community and Technical College System and Cengage

Kentucky Community and Technical College System and Civitas

Kentucky Community and Technical College System and Pearson

Lamar University and AP

Los Angeles Community College District and Ed2Go

Louisiana State University and AP

Louisana State University-Shreveport and AP

Louisiana State University and AP

Luna Community College and Blackboard

Marshall University and Blackboard

Mesalands Community College and MindEdge

Michigan State University and Bisk

Michigan State University and Coursera

Michigan Technological University and Canvas

Minnesota State Colleges and Universities and D2L

Missouri University of Science and Technology and Internet2

Mississippi Community Colleges and Blackboard

Mississippi Community Colleges and Canvas

Mississippi Community Colleges and D2L

Montana State University and Blackboard

Montana University System and D2L

Montgomery County Community College and Ed2Go

New Jersey Institute of Technology and Pearson

New Mexico Higher Education Department and Blackboard

New Mexico Highlands University and D2L

New Mexico Junior College and Canvas

New Mexico Military Institute and Canvas

New Mexico State University and Blackboard

New Mexico State University and Canvas

New Mexico State University and Centra

North Carolina Community Colleges and Remote Learner

Northern Illinois University and Blackboard

Ocean County College and Pearson

Ohio University and Pearson

Ozarks Technical Community College and Canvas

Pasadena City College and Smart Sparrow

Pennsylvania State System of Higher Education and D2L

Purdue University and All Campus

Purdue University and Wiley

Purdue University and College Network

Rutgers University and Canvas

Rutgers University and Blackboard

San Juan College and AHIMA Vlab

San Juan College and Evaluation KIT

Southeastern Oklahoma State University and AP

Southern Illinois University Carbondale and Career Step

Southern Illinois University Carbondale and Ed2Go

Southern Illinois University Carbondale and JER Group

Texas A & M and Blackboard

Texas A & M and Canvas

Texas A & M and iLaw

University of Alabama and Blackboard

University of Arizona and Coursera

University of Arizona and D2L

University of Arizona and All Campus

University of California-Berkeley and 2U

University of California-Los Angeles Extension and Trilogy Education Services

University of California-Los Angeles Extension and Instructure

University of Cincinnati and AP

University of Cincinnati and Pearson

University of Florida and 352

University of Florida and All Campus

University of Florida and Apollidon

University of Florida and Bisk

University of Florida and CEN

University of Florida and Coursera

University of Florida and Wiley

University of Florida and Pearson

University of Florida and New Horizons

University of West Florida and AP

University of West Florida and The Learning House

University of West Florida and Instructional Connections

University of Idaho and Blackboard

University of Idaho and NetLearning

University of Illinois and Pearson

University of Kansas and Everspring

University of Kansas and Blackboard

University of Mary Washington and Canvas

University of Massachusetts and Pearson Embanet

University of Massachusetts and HigherEducation.com

University of Massachusetts and Education Dynamics

University of Massachusetts and Avenue100

University of Massachusetts and GetEducated.com

University of Nebraska and iDesignEDU

University of Nebraska and Ranku

University of Nebraska and Thruline

University of Nebraska and Inside Track

University of New Mexico and Blackboard

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and 2U

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Coursera

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Time

University of North Carolina Wilmington and AP

University of North Dakota and Ed2Go

University of North Dakota and Pearson

University of North Dakota and Exeter Education

University of North Dakota and Career Step

University of North Dakota and Digital Learning Tree

University of North Dakota and Hoonuit

University of North Dakota and Kaplan

University of North Dakota and Kimberly Williams

University of North Dakota and Public Consulting Group

University of North Dakota and Professional Development Institute

University of North Dakota and Protrain

University of North Dakota and Continuing Education Associates

University of North Dakota and The CE Shop

University of North Dakota and Virtual Education Service

University of North Texas and Blackboard

University of Rhode Island and AP

University of South Alabama and Longsight

University of Southern Mississippi and Blackboard

University of Texas and AP

University of Texas and AliveTek

University of Texas and Big Tomorrow

University of Texas and Blackboard

University of Texas and Brightleaf

University of Texas and Classmate

University of Texas and CAE

University of Texas and Elephant Productions

University of Texas and Enspire

University of Texas-El Paso and Pearson

University of Vermont and Bisk

University of Vermont and Blackboard

University of Vermont and Ed2Go

Victoria College and Canvas

Victoria College and Ed2Go

Victoria College and Monterey Institution of Technology

Washington State Board for Community & Technical Colleges and Blackboard

Washington State Board for Community & Technical Colleges and Canvas

Washington State University and ANGEL Learning

Washington State University and Blackboard

Washington State University and Pearson

Washington State University and National Repository of Online Courses

Western New Mexico University and Blackboard

West Virginia University and Coursera

Notes

- Margaret Mattes, “The Private Side of Public Higher Education,” The Century Foundation, August 7, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/report/private-side-public-higher-education/.

- See TCF’s series of reports, The Cycle of Scandal at For-Profit Colleges, for an historical overview: https://tcf.org/topics/education/the-cycle-of-scandal-at-for-profit-colleges/.

- Margaret Mattes, “The Private Side of Public Higher Education,” The Century Foundation, August 7, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/report/private-side-public-higher-education/.

- For a list of online programs by enrollment, see NC-SARA 2018 Enrollment Report, National Council for State Authorization Reciprocity Agreements, October 15, 2018, https://www.nc-sara.org/sites/default/files/files/2019-07/2018_EnrollmentDataReport%20101918_FINAL.pdf.

- In July 2019, 2U indicated it would begin contracting with universities on a fee-for-service basis in addition to its long-standing tuition-share model. Lindsay McKenzie, “A Reckoning for 2U, and OPMs?” Inside Higher Ed, August 1, 2019, https://www.insidehighered.com/digital-learning/article/2019/08/01/bad-day-2u-highlights-vulnerability-online-program-management.

- “The Anatomy of an OPM and a $7.7B Market in 2025,” HolonIQ, February 14, 2019, https://www.holoniq.com/news/anatomy-of-an-opm/; Lindsay McKenzie, “A Tipping Point for OPM?” Inside Higher Ed, June 4, 2018,

https://www.insidehighered.com/digital-learning/article/2018/06/04/shakeout-coming-online-program-management-companies; Doug Lederman, “MOOC Platforms’ New Model Draws Big Bet from Investors,” Inside Higher Ed, May 22, 2019,

https://www.insidehighered.com/digital-learning/article/2019/05/22/investors-bet-big-companies-formerly-known-mooc-providers; Lindsay McKenzie, “Rival Publishers Join Forces,” Inside Higher Ed, May 2, 2019,

https://www.insidehighered.com/digital-learning/article/2019/05/02/cengage-and-mcgraw-hill-merge. - The types of contracts received in response to requests also impacted what was included in our analysis, as not all institutions interpreted the request in exactly the same way. Some institutions shared solely contracts that are clearly related to the delivery and management of their online programs, while others also included small, one-off contracts for other education-related services. Likewise, some institutions sent contracts related to the traditional side of their operations, while others included contracts that are relevant to their affiliated extension schools. For this reason, we confine our analysis to contracts that relate to services concerning the development and management of online courses and programs.

- Harriett Ryan and Matt Hamilton, “Online Degrees Made USC the World’s Biggest Social Work School. Then Things Went Terribly Wrong.” Los Angeles Times, June 6, 2019, https://www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-me-usc-social-work-20190606-story.html.

- “College Scorecard Data: Preliminary Loan Debt Data by Field of Study, ” U.S. Department of Education, available at https://collegescorecard.ed.gov/data/preliminary/.

- See ExtensionEngine’s website at https://extensionengine.com/.

- See iDesignEDU’s website at http://idesignedu.org/.

- See Academic Partnerships’ website at https://www.academicpartnerships.com/.

- See Pearson’s OPM services website at https://www.pearson.com/us/higher-education/products-services-institutions/online-program-management.html.

- Eastern Kentucky University–Pearson Embanet Master Agreement, available here; University of Florida–Apollidon Distance Education Agreement, available here.

- Carl Straumsheim, “UF Online Reboots,” Inside Higher Ed, October 23, 2015, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2015/10/23/less-two-years-after-launch-u-florida-reboots-online-education-initiative.

- Lindsay McKenzie, “A Reckoning for 2U, and OPMs?” Inside Higher Ed, August 1, 2019, https://www.insidehighered.com/digital-learning/article/2019/08/01/bad-day-2u-highlights-vulnerability-online-program-management.

- Harriet Ryan and Matt Hamilton, “Must Reads: Online degrees made USC the world’s biggest social work school. Then things went terribly wrong,” Los Angeles Times, June 6, 2019, https://www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-me-usc-social-work-20190606-story.html.

- Kevin Carey, “The Creeping Capitalist Takeover of Higher Education,” Huffington Post, April 1, 2019, https://www.huffpost.com/highline/article/capitalist-takeover-college/.

- “2U, Inc to Acquire Trilogy Education, the Leader in Powering University Boot Camps,” 2U, April 8, 2019, https://2u.com/about/press/2u-to-acquire-trilogy-education/.

- See TCF’s letters to the California State Assembly and to the U.S. House of Representatives’ Committee on Education and Labor.

- From the UCLA–Trilogy contract (available here), dated January 12, 2018: “Joint Responsibilities: Agree that the optimal price point for the PROGRAM will be determined by mutual agreement. Any amendment to the optimal price point must be agreed to in writing…The Parties agree to raise the price point if and to the extent that market factors permit.”

- Karl E. Emerson, “The Private Inurement Prohibition, Excess Compensation, Intermediate Sanctions, and the IRS’s Rebuttable Presumption,” GuideStar USA, 2009, https://learn.guidestar.org/hubfs/Docs/private-inurement-prohibition.pdf; “Intermediate sanctions – excess benefit transactions,” Internal Revenue Service, last updated August 7, 2019, https://www.irs.gov/charities-non-profits/charitable-organizations/intermediate-sanctions-excess-benefit-transactions.

- 20 U.S. Code § 1094, “Program participation agreements,” Higher Education Act, available at https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/20/1094.

- Personal communication with University of Florida officials.

- Robert Shireman, “The For-Profit College Story: Scandal, Regulate, Forget, Repeat,” The Century Foundation, January 24, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/report/profit-college-story-scandal-regulate-forget-repeat/.