During the past two presidential election campaign seasons, candidates have proposed various versions of major federal proposals to make college “free” or “debt-free,” with different interpretations of which colleges and students would be included and what costs would be covered. Finally, the rubber is meeting the road: the Biden administration and leaders in Congress have included tuition-free community college as their marquee higher education reform in this year’s reconciliation bill. A final agreement will require tough political choices to be made about policy design.

First proposed by the Obama administration in 2015, America’s College Promise (ACP)—a federal–state partnership that would deliver federal grants to states on the condition that they waive community college tuition and fees—is one step closer to becoming a reality.1 On September 8, the House Committee on Education and Labor revealed the text of its ACP legislation in the Build Back Better Act, the House’s reconciliation bill and a key piece of the Biden administration’s policy strategy for economic mobility and racial justice.2 Tuition-free community college is just one of several approaches to confronting the full array of challenges facing colleges, students, and families currently being considered. The bill also features increased investments in HBCUs and other minority-serving institutions as well as an expansion of the Pell Grant, both long overdue. But of these approaches, America’s College Promise could affect the largest number of students and would constitute a historic overhaul of the second-largest sector in higher education. It is essential that this policy be designed with equity at the forefront.

As with any initiative making sweeping change, however, the extent of ACP’s impact will be determined by the details of its construction and implementation. Though the Biden administration estimated earlier this year that it could achieve free community college in all states at a cost of $109 billion over ten years, achieving the hoped-for state participation could require a larger investment.3 At the same time, budgetary constraints are likely to force difficult policy design decisions in order to contain costs, and bill authors in Congress have numerous options for defining eligibility among students and institutions and delineating the federal role. Within the ACP framework, there are many design choices to be made that will shape which states and students benefit and by how much.

To help lawmakers and the public understand how these decisions translate to state- and student-level funding, The Century Foundation (TCF) has developed an interactive cost model for America’s College Promise. Through an online app, users can specify key design inputs and see their effects on funding and student eligibility.4 This report shares findings from TCF’s cost model and offers policy recommendations to Congress for writing the proposal into legislation.

How America’s College Promise Would Change the Federal–State Relationship

Since the nation’s founding, American public education has been primarily governed at the local and state levels. The federal government has occasionally made forays into this territory, such as when it established land-grant universities in the latter nineteenth century.5 But over the decades, generations of state lawmakers have been mostly responsible for making independent policy decisions about what kinds of public colleges would be established, how they would be governed, and how they would be financially supported by their states. As a result, the United States has fifty-one systems of higher education that are often quite dissimilar. In some states, there are very few community colleges, for example, and in others, nearly every county has its own community college.

The variation in community college systems from state to state is reflected in financial aid and tuition pricing. Despite a movement for tuition-free college that has grown quite rapidly in recent years, some states lag well behind others, offering their lowest-income residents few or no pathways to an affordable college degree.6 This contrasts with the universal free-college policies of other advanced nations,7 and it ultimately makes U.S. higher education more difficult to navigate for those whose families have little experience with it.

In the face of these differences, America’s College Promise would require all participating states to share one policy in common: the policy that students will face no tuition or fee charges in order to attend a community college in their own state at least half-time. To do this, the federal government would send states new per-student funding equal to a certain share of the nationwide median resident community college tuition and fees, with part-time students counted as a partial student. (In the Build Back Better Act, that share is 100 percent in ACP’s first year, FY 2024, and reduces incrementally to 80 percent in FY 2028.) Participating states would have to put forth the remainder of the cost in their state while maintaining pre-existing levels of fiscal support for higher education, for public four-years, and for need-based financial aid.8

Under ACP, if a state winds up with more combined federal and state funding than it needs to bring tuition to zero, then it can spend the remainder on specified uses, such as reducing unmet need at public four-year colleges.9 But if a state has community college tuition prices that are above the national average, it must invest more than just the baseline costs in order to satisfy the tuition-free requirement. As a result of these factors and states’ varying levels of wealth, the relative fiscal effort needed to participate in ACP is not equal across states.

This means that some states and populations would gain more than others. This is true of virtually any policy, but a central question for policymakers is whether all states are fiscally capable of participating and what groups would be put at the greatest disadvantage if their state does not join. For example, poorer people tend to live in poorer states, and much of the Black and Latinx populations live in states where college tuition has risen especially high. Unless certain considerations are made in crafting the funding formula, these groups are at greater risk of their state lawmakers choosing not to participate in the partnership and thus compounding existing inequities in college affordability.

These distributional questions should be top of mind for lawmakers as they write the fine print of ACP. As they do so, modeling outcomes for states and for population subgroups can serve as a guide.

Key Findings from TCF’s America’s College Promise Cost Model

The Century Foundation developed a cost model of America’s College Promise based on the House Committee on Education and Labor’s bill text as well as inferences about which aspects of the policy design could be modified to manage costs, incentivize state participation, or improve distributional equity.

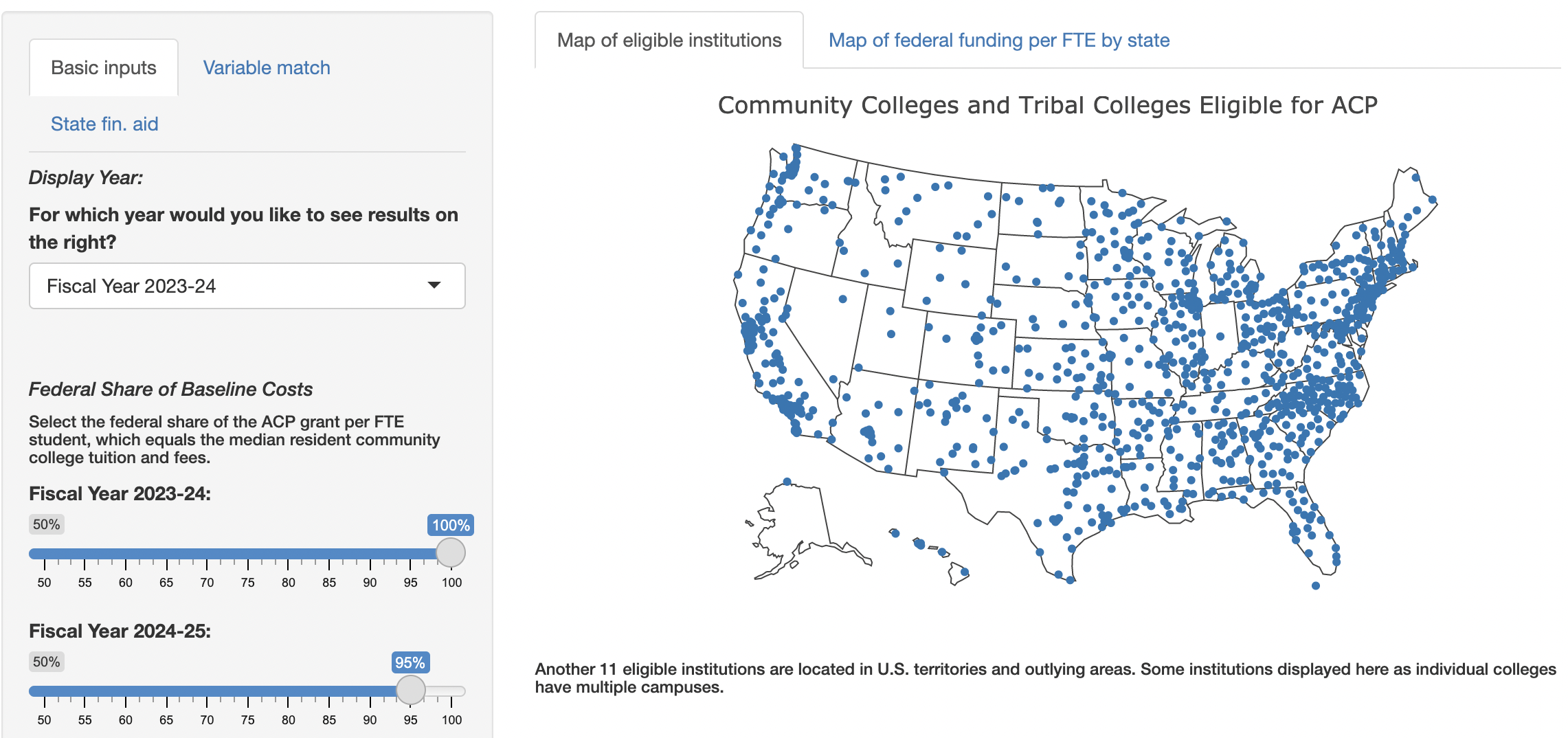

In this model, 1,029 institutions in fifty states and seven territories would qualify as either community colleges or tribal colleges, for a total of 8 million eligible students on a headcount basis. Under this model, federal allocations would total $83 billion over the first five years of ACP.

MAP 1. COMMUNITY COLLEGES AND TRIBAL COLLEGES ELIGIBLE FOR ACP

Click here to view the full interactive tool.

Source: Author’s cost model calculations using interpretation of bill text and National Center on Education Statistics (NCES) data.

TABLE 1

| Key Features of ACP | |

| Qualifying institutions | 1,029 |

| Eligible students (full-time equivalent) | 3,957,597 |

| Eligible students (headcount) | 8,119,572 |

| America’s College Promise funding per FTE | $4,478 |

| New federal funding for community collages (FY 2024) | $17.7 billion |

| New federal funding for community colleges (FY 2028) | $83.0 billion |

| Note: This assumes an average annual inflation rate equal to the average over the past twenty years and full participation among all states, territories, and tribal colleges. Source: Author’s cost model calculations using interpretation of bill text and National Center on Education Statistics (NCES) data. |

|

The cost model reveals several key takeaways.

- ACP’s benefits would go beyond community college tuition. The first year of ACP would see about $4.7 billion per year become newly available to twenty-five states for flexible spending within education, because their ACP funding would exceed the amount needed to eliminate tuition and fees. This overflow money rewards the states that have prioritized affordability at community colleges—such as California, New Mexico, and Nebraska, for example—allowing them to invest this new money into their public universities, dual enrollment programs, and interventions to improve student outcomes. More is at stake than just community college tuition when these states decide to participate in ACP. If conservative lawmakers in low-tuition states decline to join ACP, saying, “We’ve already achieved affordable community college on our own,” they would be turning down tens of millions of dollars in new, ongoing federally funded investments in quality educational opportunities for their constituents.

In addition, because ACP funding would displace state financial aid for tuition and fees, another $2.2 billion per year in state funds nationwide also becomes available and could be redirected from existing financial aid for community college students (almost all of which is currently used for tuition and fees) to non-tuition aid for these same students. - ACP would mark an especially significant investment in Hispanic-Serving Institutions (HSIs). Under the bill, $7.2 billion of the $17.7 billion in new federal funding in FY 2024 would go to Hispanic-Serving Institutions, almost half of which (48 percent) are community colleges. By comparison, new Title V funding to HSIs in FY 2020 was only $69 million, about 1 percent of the newly proposed amount.10

- Some states would need to increase their annual investment in community colleges by 50 percent or more in order to participate in ACP. As previously described, some states have let community college tuition prices rise high, and these same states are often those that do not have a strong track record of investment in community colleges. Because the cost of waiving tuition and fees in those states would exceed the funding from ACP, new investment required from those states would be large—as much as 40 percent in Pennsylvania, 51 percent in South Dakota, and 199 percent in Vermont, even in the first year of ACP when the state share of costs is lowest. In the aggregate, state annual education appropriations would need to increase 2.8 percent in FY 2024, including states’ cost of entry into ACP and any remaining costs of waiving tuition and fees, but this figure rises to 10.7 percent in FY 2028 as the state share of costs increases. (See Figure 1.)

FIGURE 1

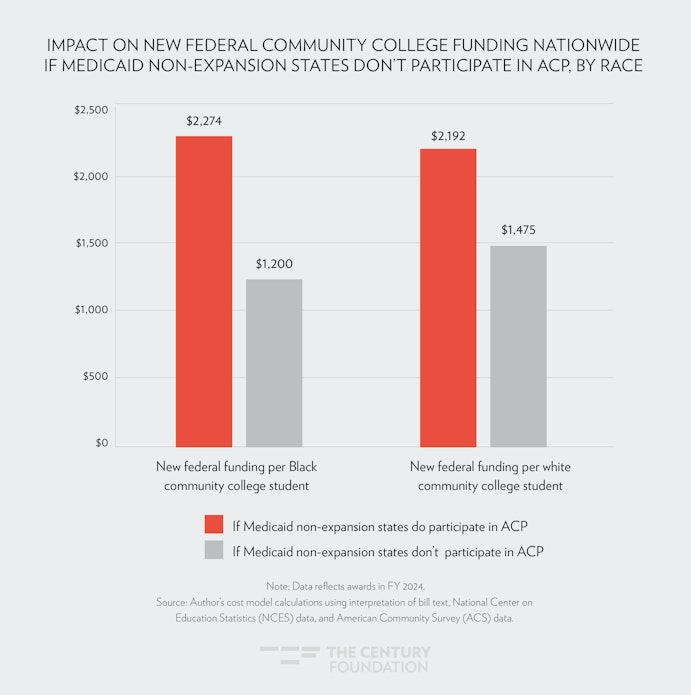

- Without full participation by all states, lost benefits could disproportionately befall Black residents. If all states participate, new federal funding for community colleges would equate to slightly more funding per Black resident than per White resident,11 due to more federal funding flowing to states with disproportionate shares of Black residents. But this would change if some states opt out. For example, if the same twelve states that have rejected Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act—which are largely located in the Sun Belt—choose not to join ACP, federal funding per Black resident nationwide would then be less than the new federal funding per White resident.12 Moreover, if these twelve states do not participate in ACP, their rejection of new funds would have an outsized impact along racial lines among enrolled students: new federal funding per Black community college student nationwide would be 46.2 percent lower if these twelve states do not participate in ACP as compared to if they did. (See Table 2.)

It is difficult to predict whether state legislators and governors will opt in or out of ACP in the same way they did for Medicaid expansion, but Congress should consider an option for covering a higher share of costs in states such as these to incentivize participation. Making the federal match proportional to a state’s child poverty rate, for example, would give Sun Belt states federal matches that are one-third higher on average than the rest of the nation.13

FIGURE 2

For all the nuances of this complex legislation, these findings tell a straightforward story. ACP would spur a dramatic increase in investment in some of the nation’s most underserved institutions and populations; however, nonparticipation among states for reasons fiscal or otherwise would threaten the potential of ACP to help bring down educational barriers by race and class.

Policy Recommendations

To increase the likelihood that states would participate in ACP and help advance lasting improvements to American higher education, Congress should take the following steps.

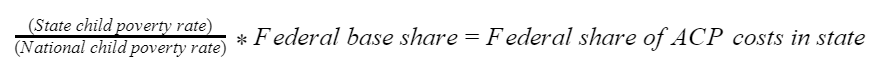

- Target more federal funds to poorer states using a variable match rate formula. If ACP is to fulfill its mission of providing an upward ladder for underserved groups, then it needs states to participate, especially those that historically have had the fewest resources. These same states, particularly those in the Sun Belt, are home to an outsized share of Black, Latinx, and low-income Americans. While Congress has shown a commitment to states by starting the federal share of baseline ACP costs at 100 percent, poorer states may be wary of the declining federal share (80 percent in FY 2028) and the requirement to maintain higher education funding at current levels. By defining the federal match rate as a function of state wealth through a simple formula, Congress would increase the incentive for lower-resourced states to participate. An example of this formula using states’ child poverty rates is provided below.14

This formula may also help diminish the potential critique that ACP needlessly sends money to wealthy states that have already enacted a form of tuition-free community college by making the biggest beneficiaries of the partnership lower-wealth states where net community college tuition remains high. (See Map 2 and Table 2 for the potential impact of such a formula.)

This formula may also help diminish the potential critique that ACP needlessly sends money to wealthy states that have already enacted a form of tuition-free community college by making the biggest beneficiaries of the partnership lower-wealth states where net community college tuition remains high. (See Map 2 and Table 2 for the potential impact of such a formula.)

MAP 2

TABLE 2

| Five State’s Federal Funding for Community College Using an ACP Formula Based on Child Poverty Rate | ||||

| State | State child poverty rate | National child poverty rate | Adjustment to federal share | Federal funds per FTE |

| West Virginia | 23.8% | 18.5% | ↑ 28.6% | $5,761 |

| Georgia | 21.5% | 18.5% | ↑ 16,2% | $5,204 |

| Indiana | 18.5% | 18.5% | 0% | $4,478 |

| Illinois | 17.1% | 18.5% | ↓ 7.6% | $4,139 |

| Connecticut | 13.3% | 18.5% | ↓ 28.1% | $3,129 |

| Note: Table reflects awards in FY 2024. Source: Author’s cost model calculations using interpretation of bill text and National Center on Education Statistics (NCES) data. |

||||

- Add state support for FAFSA completion as an allowable expense for ACP overflow funds. The ACP bill text in the Build Back Better Act released September 8 features various changes from its predecessor, the America’s College Promise Act of 2021.15 Among these is a newly added provision that students who are U.S. citizens must complete a Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) in order to benefit from the federally-funded ACP grant.

The upside of this addition is that students enrolling through ACP will learn if they are eligible for the Pell Grant, which helps support college completion by reducing unmet need for living costs and other basic needs. The downside is that, all too often, the same students who need financial aid the most struggle to complete the FAFSA and navigate administrative hurdles such as income verification. Under this new provision, noncompletion would lock these students out from both ACP and the Pell Grant.

Direct support for FAFSA completion is vital for the implementation of large-scale FAFSA requirements, and requiring the FAFSA for free tuition under ACP would be no different.16 Unfortunately, high schools and community colleges alike frequently lack the staffing to help their students complete the FAFSA, which means states will need to increase their investment in these professional resources in order to ensure equal access to ACP. The first thing Congress should do to support these efforts is to designate these investments as an allowable use of ACP overflow funds, the $4.5 billion funding stream that would reach about half of states during ACP’s first year. - Provide additional funding to help states waive special programmatic fees. Many community college programs charge students extra fees for special costs that are required for participation in the program. Nursing programs, for example, require students to pay for certification, uniforms, and similar costs that other students at the same college would not need to pay. These costs rack up quickly for students, which means these costs would rack up quickly for states seeking to join ACP and waive tuition and fee charges. In Colorado, for example, the sum of the state’s community college tuition and fee revenue is two-thirds more than its standard tuition and fees multiplied by FTE enrollment.

Currently, the phrase “tuition and fees” is not defined in the bill text of ACP, leaving the decision to the Education Department. If special programmatic fees are not covered, a student could be misled into thinking they can enroll in the program of their choosing for free, only to face a fee charge of several thousand dollars (or more). Congress should state clearly in the bill text of ACP that “tuition and fees” covers all tuition and fees, and it should create a special fund to supplement the baseline federal allocation, covering fee costs that could be missed in the median measure of tuition and fees. - Go beyond ACP and couple it with investment in HBCUs and an expansion of the Pell Grant. While it is encouraging that the ACP model shows that 40 percent of new funding would go to Hispanic-Serving Institutions, the model also shows that Historically Black Colleges and Universities and Predominantly Black Institutions would not benefit as strongly. It would take more than just ACP to close the Black–White attainment gap that endures as a legacy of slavery, segregation, and ongoing systemic racism. Alongside ACP, Congress should invest in the finances of HBCUs, as my colleague Denise Smith has outlined, and the Biden administration’s proposed investments in tuition subsidies at HBCUs and other MSIs.

ACP also does relatively little for non-tuition costs, except for (1) the estimated $2.4 billion per year in expected overflow dollars that states would be free to use for this purpose, and (2) the financial aid previously used for community college tuition that ACP makes available for stipends to students. Congress should enact an increase to the Pell Grant that features the accountability recommendations my colleague Robert Shireman has proposed.

Conclusion

The most important measure of a universal policy intervention such as national tuition-free community college is how well it serves those who have been failed the most by existing policy. A young American’s income and race continue to heavily predict their education destiny.17 ACP won’t solve this alone, but it can help ensure that when someone in the United States looks around themselves, they can see at least one path to a high-quality degree at a nearby, trusted institution.

TCF’s cost model shows that the ability of America’s College Promise to improve college affordability for underserved groups depends on whether it is a true partnership: whether states, especially poorer states, make the commitment and investment to join. Congress should include the above recommendations to increase the likelihood all states participate and that this funding does not fail to reach those with the greatest needs.

Acknowledgment: Special thanks to Nick Hillman and Vero Minaya-Lazarte for reviewing the methodology for our cost model, and to David Socolow for informing TCF about the funding implications of how tuition and fees are defined in the bill text..

To request the methodology of our cost model and app, please email Peter Granville at [email protected].

Notes

- “White House Unveils America’s College Promise Proposal: Tuition-Free Community College for Responsible Students,” White House Office of the Press Secretary, January 9, 2015, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2015/01/09/fact-sheet-white-house-unveils-america-s-college-promise-proposal-tuitio.

- “Markup of Committee Print to comply with the Reconciliation Directive included in Section 2002 of the Concurrent Resolution on the Budget for Fiscal Year 2022, S. Con. Res. 14.”, U.S. House of Representatives, September 9, 2021, https://docs.house.gov/Committee/Calendar/ByEvent.aspx?EventID=114029.

- Scott Jaschik, “Biden Proposes Free Community College, Pell Expansion,” Inside Higher Ed, April 28, 2021, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2021/04/28/biden-proposes-free-community-college-18-trillion-plan.

- This app is publicly available at https://petergranville.shinyapps.io/AmericasCollegePromiseModel/.

- See “Land-Grant University FAQ,” Association of Public and Land-Grant Universities, https://www.aplu.org/about-us/history-of-aplu/what-is-a-land-grant-university/.

- Jen Mishory and Peter Granville, “Policy Design Matters for Rising Free College Aid,” The Century Foundation, June 6, 2019, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/policy-design-matters-rising-free-college-aid/.

- Marnette Federis, “Biden, Sanders have free college plans. They might learn from other countries,” Public Radio International, March 19, 2020, https://www.pri.org/stories/2020-03-19/biden-sanders-have-free-college-plans-they-might-learn-other-countries.

- The state’s required contribution to eliminate the tuition and fees would also eliminate the need for state financial aid for tuition, freeing up these resources for financial aid for community college students’ non-tuition expenses. Currently, there is quite little state financial aid available to help students pay for non-tuition expenses like housing and food. But if a state joined ACP, all of its existing tuition-based state financial aid for community college students could be delivered as non-tuition aid because these students would not receive tuition charges in the first place.

- See Section 789 of the bill.

- New awards totaled $69,354,131 in FY 2020, according to Education Department reporting. See “Awards” page under “Developing Hispanic-Serving Institutions Program – Title V,” Washington, D.C.: U.S Department of Education, n.d., accessed September 4, 2021, https://www2.ed.gov/programs/idueshsi/index.html.

- Our model measures funding per resident aged 18-35 without a college degree, the predominant population served by community colleges.

- The list of Medicaid non-expansion states is Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kansas, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Wisconsin, and Wyoming. See “Status of State Action on the Medicaid Expansion Decision,” San Francisco, CA: The Kaiser Family Foundation, accessed September 4, 2021, https://www.kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/state-activity-around-expanding-medicaid-under-the-affordable-care-act/.

- Here we count Alabama, Arkansas, Arizona, California, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Kansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Louisiana, Mississippi, Nevada, New Mexico, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Utah as Sun Belt states. If each state’s federal share of costs is based on its child poverty rate, then Sun Belt states would see an average federal share that is 32.9 percent higher than the average for all other states.

- Congress could choose to cap the federal share at 100 percent or allow it to go above 100 percent in order to assist states that have community college tuition rates above the national average (and would have to appropriate new funding to waive tuition and fees).

- H.R. 2861, 117th Congress, introduced by Representative Andy Levin [D-MI-9] on April 28, 2021, accessed September 4, 2021, https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/2861. S. 1396, 117th Congress, introduced by Senator Tammy Baldwin [D-WI] on April 27, 2021, accessed September 4, 2021, https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/senate-bill/1396.

- Peter Granville, “Should States Make the FAFSA Mandatory?”, New York, NY: The Century Foundation, July 29, 2020, https://tcf.org/content/report/states-make-fafsa-mandatory/.

- For example, a longitudinal study of ninth grade students in 2009 shows that 74 percent of White non-Hispanic students and 85 percent of Asian non-Hispanic students had attended college by February 2016, compared to only 62 percent of Black non-Hispanic students, 59 percent of Hispanic students, and 48 percent of Native American non-Hispanic students. In the same study, only 59 percent of those with total family incomes under $35,000 attended college, compared to 92 percent of those with total family incomes over $115,000. (Author’s analysis of data from the National Center for Education Statistics’ High School Longitudinal Study of 2009, available at https://nces.ed.gov/datalab. For more information about the study, please see https://nces.ed.gov/surveys/hsls09/.)