As colleges seek to recover from the effects of the pandemic,1 including enrollment and revenue shortfalls, student recruitment becomes increasingly important. Since predatory recruitment tactics historically increase2 during times of economic downturn, particularly at for-profit institutions, schools need to be vigilant in ensuring that their efforts to attract students do not stray into a realm of questionable practices. The challenge of maintaining integrity may become even greater than before, as public and private nonprofits now outsource increasing amounts of their online programs and processes—including student recruitment functions—to for-profit online program managers (OPMs),3 whose recruitment models sometimes mirror those seen at many for-profit colleges.

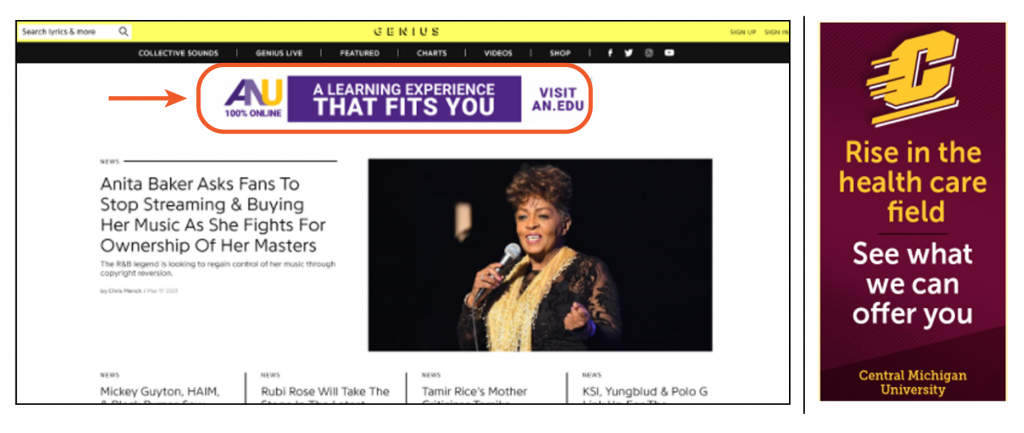

Since the start of the pandemic, The Century Foundation has been monitoring online advertisements4 of institutions with large online enrollments, in an effort to call into question indicators of predatory or otherwise worrisome practices. While an advertisement alone is not enough to conclude predatory behavior, when a school’s advertising history is examined in combination with institutional investment in the quality of education, the picture of whether there may be harms to students becomes clearer. This report examines how a range of colleges target prospective students through advertisements placed on websites, and although none of the practices are blatantly problematic by themselves, the report offers recommendations on how institutions can avoid advertising in ways that could be considered harmful.

Using data generated by the advertising tracking software Adbeat, The Century Foundation looked at the top websites used by colleges that engage in display advertising. We analyzed August 2020 display ad data spanning a thirty-day period for 190 institutions—a cohort consisting of the 100 institutions with the largest online enrollments and 90 additional institutions advertising under terms we’ve identified that warrant a closer look.5

Display Advertising and Ad Networks

Display advertising is perhaps the oldest form of digital marketing. Display ads (also known as banner ads) appear in the form of a picture, video, and/or text alongside a website’s content across the Internet.

In the early days of the Internet—before there were robust Internet search engines and social media—webpages were static and lacked interactivity. Much like advertisers who would pay for their ad to appear on a magazine page or during a television commercial break, Internet advertisers would pay a flat rate for their ad to appear as a static image in set position on a website’s page. These first Internet ads were not tailored to viewers beyond a general understanding of what cohorts comprised AOL or MSN customers. These websites that host the advertisements of display advertisers are known as publisher sites, and today include just about any type of website that a user could visit, such as usnews.com or reddit.com, where advertisers pay varying amounts for hosting their advertisements.

As the Internet’s connectivity and interactivity increased over the years, digital advertising advanced in its ability to target specific consumer profiles. Today, a user’s experience on the Internet is greatly impacted by their browsing and search history, zip code, where they have traveled while holding a connected device such as a smartphone, their online shopping habits, consumer profiles that include algorithmic assumptions on things such as educational background, and more. It is no wonder then, that as the amount of data generated about users grows, so too do concerns over digital segregation.6 Everything users do and everywhere they go in their digital lives leaves behind enough of a trail for advertisers to now have laser-sharp targeting abilities.

Some advertisers still place ads through the traditional mode of directly buying a location on a website, as this allows the advertiser direct involvement7 in ad placement and price setting. However, it is becoming increasingly common for advertisers seeking a broad reach—among them, colleges and universities—to engage in more automated forms of display advertising,8 involving ad networks and third-party platforms9 to allow buying from many websites at once.

Ad networks10 are of particular note as they serve as an intermediary between advertisers and publisher sites, setting price ranges and often targeting capabilities on the advertiser’s behalf. These capabilities11 can span contextual targeting, demographic targeting, targeting of consumers that have previously visited an advertiser’s website, targeting via generating “lookalike audiences” (formed using consumer contact information to find consumers similar to those already in an advertiser’s system), among others. The Google Display Network,12 for example, allows advertisers to target consumers by age, gender, household income, and parental status.

As it is the ad network that executes the targeting, the advertisers have limited control13 over where their ads appear. So, unlike the traditional direct-buy method, where advertisers are explicitly choosing the websites that would attract their target audience, advertisers buying space through an ad network are less involved in deciding which websites host their ads, as it is the network’s algorithms that determine where ads are served to users. That being said, the audience-targeting intent of an advertiser cannot be easily determined based on the site where an ad appears when placement is through broad display advertising via ad networks. However, advertisers can exercise some control over where on the Internet their ads are placed by excluding or including14 specific targets, such as audiences, websites, content, or keywords, though it is unclear if these controls exist amongst all ad networks. Responsible advertisers take advantage of this option to protect their brand.

Although many factors influence where a display advertisement appears, ad placement can still carry significant implications. In instances where an advertiser is directly choosing the site where to host its ad, the site it chooses can be a direct reflection of its targeting intent. So, an ad placed on a military site via a direct transaction between that site and the advertiser could mean that the advertiser is targeting members of the military. In cases where the advertiser is less directly involved in selecting the publisher site, ad placement can reflect the level of attention and control advertisers maintain in placing ads. An ad placed on a military site via an ad network could still mean that the advertiser wished to target a military audience, but it could also be an unintended result of the ad network’s own algorithms to determine consumer targeting over a broad set of websites chosen by the ad network. It is for this reason that it is important for institutions, especially those dedicating large budgets to advertising, to exercise prudence when working with ad networks.

TCF used information from Adbeat to understand where institutions paid the most to place display ads around the Internet. While advertisers of all stripes do their best to reach specific target audiences, it was not clear from our analysis whether the targeting we identified was intentional, as the data do not show how an ad was placed nor if measures for accurate targeting were taken. Even so, the following analysis offers a glimpse into where colleges and their prospective students may run into each other online.

Types of Publisher Sites Used

TCF limited its analysis to the three publisher sites where each college dedicated the most advertising spending, and so does not account for every publisher site used by an institution. Within TCF’s sample of 178 institutions, 103 placed ads on sites that cost more than $1,000 each. This cohort consists of 25 for-profit institutions, 47 nonprofit institutions, and 31 public institutions. TCF limited its analysis to this set of institutions. In August and September of 2020, this group of colleges placed ads on 123 unique publisher sites, listed here.

In this set of publisher sites where colleges placed ads, Harvard Business School (HBS) topped the list by spending $655,200 to place ads on three sites between August and September. Yahoo was its highest priced publisher site at $473,000, followed by the Washington Post at $91,000, and the Guardian at $90,000. HBS’s most expensive ads on Yahoo web pages were run on the home page for $91,000, alongside an article titled “Harvard’s campus will not open for fall semester for the 1st time in 384 years” at $11,000, and alongside another article titled “Zoetis’ (ZTS) Q2 Earnings and Revenues Surpass Estimates,” at $7,000. Xavier University, in Cincinnati, had the next most expensive three publisher sites, totaling $494,000, all exclusively on Youtube. Xavier’s three most expensive ads—run on Youtube ahead of videos aimed at children, and thus by proxy, their parents—totaled $26,400.

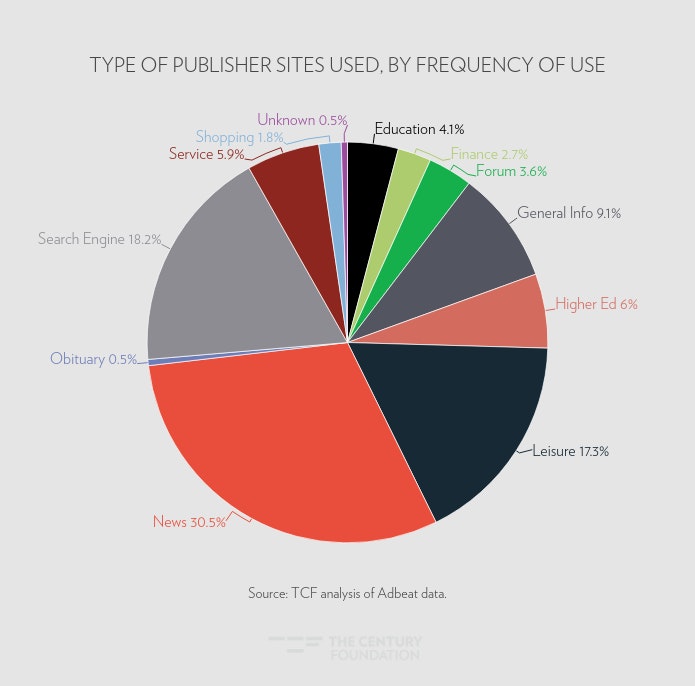

To get an idea of the types of consumer interests institutions may target, TCF assigned each publisher site a category based on the function it most apparently served. Every publisher site falls into one of the following twelve categories: education, finance, forum, general info, higher ed, leisure, news, obituary, professional association, search engine, service, and shopping. It should be noted that these classifications are based on TCF’s own determinations and so cannot be taken as an absolute representation of the consumer interests being targeted.

“Education” is defined as websites with educational resources targeted at K–12 students or parents of K–12 students. “Finance” refers to websites centered on financial news and advice. “Forum” refers to open discussion websites, such as Reddit.com. “General info” refers to sites that provide information relevant to all audiences, such as weather forecasts. “Higher ed” includes sites with higher education news and advice. “Leisure” includes all entertainment sites, which TCF defines to be sites whose primary purpose is not educational or news. “News” includes websites with all levels of current events and politics. “Obituary” refers to online obituaries. “Professional association” includes websites for professional distinctions, such as the American Bar Association. “Search engine” is defined as sites primarily used to guide users to other websites, such as Yahoo and Google. “Service” refers to sites of service providers, such as websites of cable providers. “Shopping” includes any online store or marketplace, such as Amazon. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

The majority of publisher sites fell within the categories of news, search engine, and leisure, with news sites used the most at 73 times, search engine sites 44 times, and leisure sites 40 times. The two least-used types of sites were obituary and shopping sites. Public institutions mostly advertised on news and general info sites, advertised the least on finance sites, and did not advertise at all on obituary, service, or shopping sites. Private nonprofits mostly advertised on news, leisure, and search engine sites, and advertised the least on education and obituary sites (there was only one use of an obituary site in our sample, by AT Still University, for $4,000). For-profit institutions also advertised the most on news, leisure, and search engine sites and advertised the least on finance and forum sites.

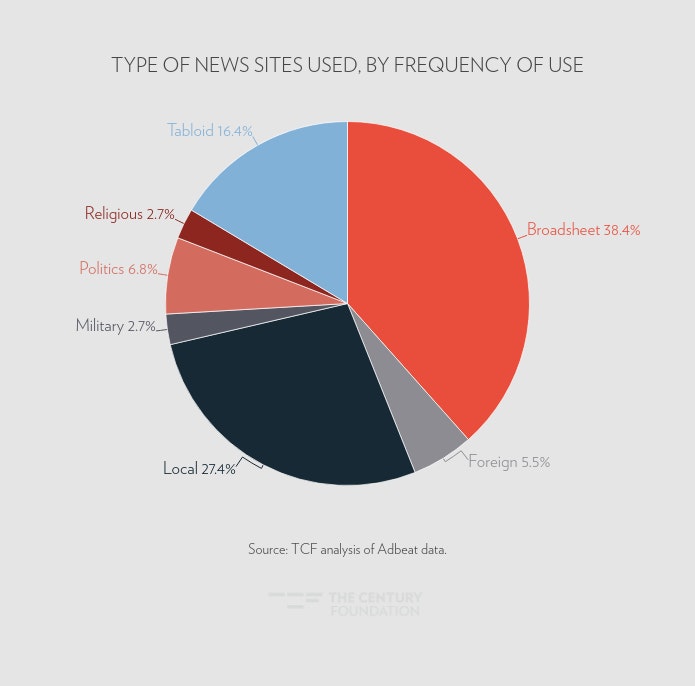

As part of the analysis, TCF broke down the news and leisure categories into more specific subcategories. News sites were classified as tabloid, broadsheet, local, foreign, politics, religious, and military (see Figure 2).15 Private, nonprofit institutions most frequently advertised on news outlets. Among news websites, private nonprofits placed ads most often with broadsheet news services. While news sites were not the most frequent advertising outlets for public or for-profit colleges, the types of news outlets where their ads appeared may still be instructive. Public institutions’ ads appeared most often in local news outlets, and for-profit college ads were fairly evenly split between tabloid and broadsheet sites. Overall, military news sites were used the least across sectors.

Figure 2

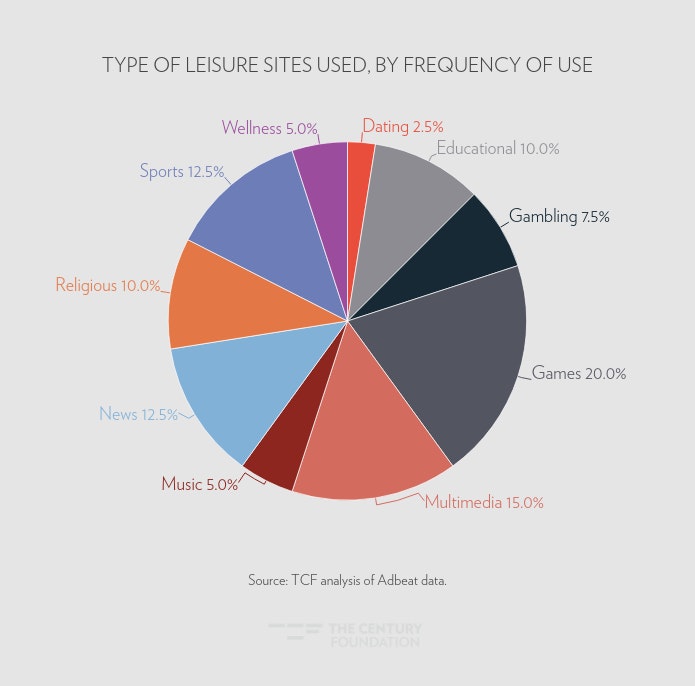

TCF then broke down the next most-used category of publisher sites—leisure sites—into the subcategories of dating, educational, gambling, games, home, multimedia, music, news, religious, sports, and wellness (see Figure 3).

Figure 3

Within this breakdown, for-profit institutions mostly advertised on gaming sites, followed by sports and news sites, and did not advertise at all on educational, music, or dating sites. Nonprofits mostly advertised evenly between religious and multimedia sites. Publics placed very few ads on leisure sites, but the ones that did were fairly evenly split between gaming, educational, gambling, music, and news sites.

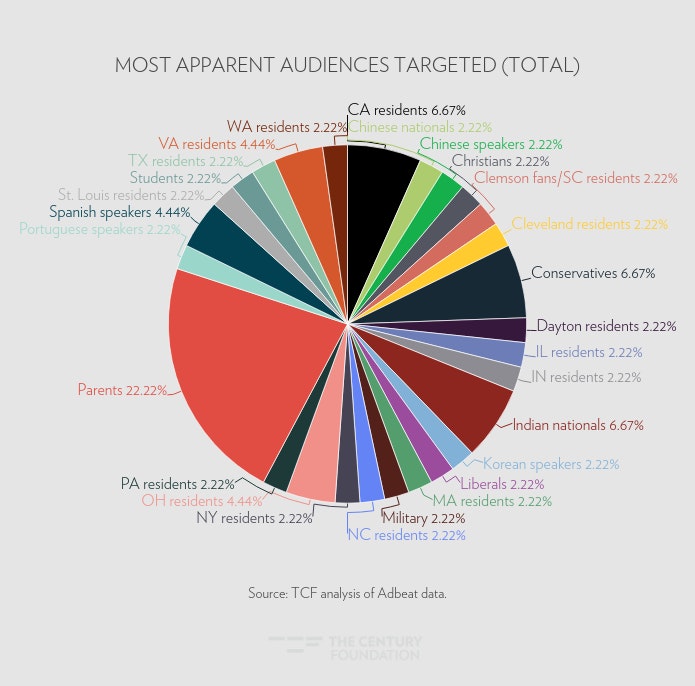

Yahoo appeared as a publisher site 20 times in the sample, and Youtube appeared 19 times, which were the most frequently occurring websites where colleges placed ads that cost over $1,000. In other words, certain institutions in our study paid at least $1,000 to place at least one ad on one of these sites. While it is hard to come to any conclusions about the demographics being targeted based solely on the type of publisher site used, TCF assumed that a certain demographic was the primary audience of an ad if a site was in a language other than English, or if the site was based out of a region not local to the institution. That being said, within this set, 47 webpages appeared to be directed at specific demographics. Of these 47 sites, nonprofit institutions accounted for 21, public institutions accounted for 14, and for-profit institutions accounted for 12.

Figure 4

One-third of the URLs seemingly directed at specific demographics were found on Youtube, while the others were dispersed between foreign and local news sites, and weather sites. The Youtube videos where institutions placed ads appeared to be most discernibly targeted at students, spanish speakers, portuguese speakers, korean speakers, Christians, and parents. Of all the demographics targeted, parents were the most targeted group. For-profit and other online colleges have historically sought to specifically enroll student parents, particularly single mothers.16 While the numbers in a relatively small sample could be the result of coincidence, this demographic is particularly vulnerable to predatory advertising, and so targeting to this group should be monitored closely.

Among ads that ran in Youtube videos, Full Sail University was the only institution targeting students generally; ECPI University had ads targeting spanish speakers; American Public University had ads targeting portuguese speakers and Christians; Capella University had ads targeting korean speakers; and Colorado State University, Strayer University, and Xavier University had ads targeting parents.

News sites were the second most used type of publisher site that most apparently targeted specific demographics. A handful of institutions placed ads on foreign news sites. A news site based out of China had ads from George Washington University, and news sites based out of India had ads from Chamberlain University, Emory University, and the Ogle School. Out of the fourteen institutions that advertised on local news sites, three were schools that are not located in the same geographic location as the news site’s target audience. The institutions that advertised outside of their regions were Middle Tennessee State University, advertising to Pittsburgh residents; Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University, advertising to New Yorkers; and Alliant International University, advertising to Massachusetts residents.

Why This Matters

It is important to remember that although advertisers can place their content in specific locations should they choose to do so, ads increasingly follow individual Internet users around instead. Because of this, it is not necessarily clear whether the ads TCF analyzed appeared where they did because of targeting based on student populations the schools hoped to reach. Even so, understanding how institutions, along with all advertisers, are targeting consumers is essential for addressing irresponsible advertising. A focal point in all advertising is consumer discernment of whether what’s being advertised is worth their money. When it is not straightforward how to gauge the product’s value—as is often the case with education—it becomes difficult for consumers to make this determination. This makes it even more crucial that institutions advertise carefully, and begs the question of whether institutions should be engaging in automated advertising at all.

As the pressures of an increasingly globalized economy make it unrealistic for educational institutions to avoid advertising, they should at least make strides to advertise carefully and increase transparency around their advertising initiatives. Colleges—especially those spending large amounts on advertising—should strive to ensure that the audiences viewing their ads reflect a population that the schools would serve well. TCF spoke with representatives of some of the institutions in the sample about their digital advertising practices, and they indicated several measures that all schools can take to focus on the right audience for them while also protecting their brand.

Recommendations for Institutions and Policymakers

The greatest recommendation for institutions that want to advertise responsibly is that they dedicate the resources needed in order to do so. One institution TCF spoke with said that, although advertising through an ad network would be more convenient, it would require trusting the network to ensure relevant targeting. Instead, this school opts to purchase ad space directly from publisher sites, which it said provides them greater transparency and control over ad placement, and thus is more cost effective for its small-scale advertising needs. Another institution said that pay-per-click17 advertising most effectively meets its marketing needs because the ads served correspond directly to the consumer’s search interest. It is worth noting, however, that tailoring pay-per-click ads requires the advertiser to determine which search terms the ad should respond to, and which it should not respond to, and not all institutions dedicate enough resources to do this properly.

The most direct routes for placing ads seem to guarantee better results for responsible ad placement, but direct ad placement can be very time consuming for advertisers that serve a wide-ranging audience, and so institutional capacity seems to be the major driving factor in advertisers’ decision to place ads through an ad network. But this limited involvement in targeting decisions subjects the institution to the risk of having its ads appear in unwanted places, potentially leading to wasted public and private resources as well as the targeting of groups that the school would not well serve.

For this reason, institutions should only engage in online display advertising to the extent they have the capacity to do so responsibly. Institutions should have direct involvement with choosing the publisher sites where their ads appear, and if an institution must outsource in order to achieve this, then it should contract with specialist marketers or ad agencies that can effectively assist in quality control. The American Association of Advertising Agencies has required that its members follow policies18 on safe brand promotion that include evaluating and updating site exclusion lists, and assessing an ad’s risk factor through a Brand Suitability Framework.19 Institutions should establish similar policies and policymakers should implement similar risk evaluation frameworks to more easily identify predatory advertising.

Finally, all consumers in general should be made more aware how they are identified and tracked. Many websites have started indicating when they use cookies—a method of collecting data about Internet users who visit their site—to track browsing behavior so that consumers have a better sense of what information is being collected about them on the Internet. Certain browsers also give consumers the ability to see basic information about why they receive certain ads. For example, consumers with a Google account can see the information Google assumes about them to personalize their ads by visiting adssettings.google.com. Google also provides basic information about how to control the ads you see and gives the option to turn off ad personalization.

Transparency practices such as these are a good start, but increased ad transparency should be the norm on every platform, especially as increased regulations20 in display advertising and innovations in digital marketing push advertisers toward search engine and social media advertising that allow for more natural-looking21 ads able to easily fly under the radar of the consumer. Colleges and universities, among all advertisers, should clearly identify when an ad is an ad, whether it be paid influencer content on social media, a native ad disguised as an article, or embedded in search results of a “best colleges” list.22 This level of transparency is a fair tradeoff for the amount of user-generated data mined and monetized by advertisers and advertising platforms.

Looking Forward

Achieving responsible and effective digital advertising is an upstream battle, as innovations to enhance convenience for the advertiser often add obscurity to an already opaque industry. Colleges racing to reach as many students as possible to both keep up with each other and attempt to offset the effects of the pandemic may be incentivized to dive headfirst into large-scale, automated advertising, much of which is ultimately funded by taxpayer dollars. With already limited student and public resources at risk, along with potentially exacerbated risks to student access and equity, colleges must engage in proactive and responsible advertising.

As TCF continues to monitor this space, it welcomes all input and information from the public. Information on any questionable ads or other relevant notices can be sent to [email protected].

Notes

- Coronavirus Coverage, series, Inside Higher Ed, https://www.insidehighered.com/coronavirus.

- See TCF’s series of reports, The Cycle of Scandal at For-Profit Colleges, for an historical overview: https://tcf.org/topics/education/the-cycle-of-scandal-at-for-profit-colleges/.

- Taela Dudley and Stephanie Hall, “Dear Colleges: Take Control of Your Online Courses,” The Century Foundation, September 12, 2019, https://tcf.org/content/report/dear-colleges-take-control-online-courses/.

- Taela Dudley, “College Marketing in the COVID 19 Economy,” The Century Foundation, August 18, 2020, https://tcf.org/content/report/college-marketing-covid-19-economy/.

- This set of terms was developed during the course of TCF’s monitoring of college advertising across platforms such as Google Search, Facebook, and Internet web pages. While use of the terms by themselves may not be problematic, our monitoring strategy includes a process for making a determination of whether ads with these terms make unjustifiable claims, target vulnerable groups, or correspond to something unrelated to what is being advertised.

- Cathy O’Neill, Weapons of Math Destruction (New York: Crown Books, 2016).

- Dan Golden, “Direct Buy Advertising & Marketing: Pros & Cons,” October 20, 2016, https://befoundonline.com/blog/benefits-drawbacks-placing-direct-ad-buys/.

- “The Beginner’s Guide to Programmatic Advertising,” Digital Marketing Institute, January 3, 2020, https://digitalmarketinginstitute.com/blog/the-beginners-guide-to-programmatic-advertising.

- “What is the Difference between a DSP and an Ad Network?” Goodway Group, https://goodwaygroup.com/blog/difference-between-dsp-and-ad-network.

- “Understanding Ad Networks,” Mopub, 2017, https://www.mopub.com/content/dam/mopub-aem-twitter/migration/39639-mopub-understanding-ad-networks.pdf.

- “5 Different Types of Targeting,” Criteo, November 28, 2018, https://www.criteo.com/blog/5-types-of-targeting/.

- “About demographic targeting,” Google, https://support.google.com/google-ads/answer/2580383?hl=en.

- Ginny Marvin, “MarTech Landscape: What Is An Ad Network?” Martech, December 30, 2015, https://martechtoday.com/martech-landscape-what-is-an-ad-network-157618.

- “Digital Marketing—Study Notes: Refine where your ads show,” Digital Marketing Institute, https://digitalmarketinginstitute.com/resources/lessons/display-advertising_exclusion-targeting_fk1k.

- News sites were classified based on the type of readership or demographic they targeted. Tabloid: image-led content. Broadsheet: text-led content and deeper analyses. Local: targeted at a city or state. Foreign: directed at nationals of another country. Politics: political news. Religious: news targeting certain religions. Military: military news.

- “Quick Figures: Single Mothers Overrepresented at For-Profit Colleges,” The Institute For Women’s Policy Research, September 2017, https://iwpr.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Q063_9.7.17_Single-Mothers-are-Overrepresented-in-For-Profit-Colleges.pdf.

- “Pay-Per-Click Advertising: What Is PPC & How Does It Work?” Wordstream, https://www.wordstream.com/pay-per-click-advertising.

- “Cross-Industry Collaboration to Redefine Brand Suitability in Trusted News Environments,” 4A’s Advertiser Protection Bureau, https://www.aaaa.org/index.php?checkfileaccess=/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/4As-APB-Cross-Industry-Collaboration-to-Redefine-Brand-Suitability-in-Trusted-News-Environments_7-14-2020.pdf&access_pid=86045.

- “Advertising Assurance: Brand Suitability Framework,” 4A’s, https://www.aaaa.org/index.php?checkfileaccess=/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/APB-Brand-Suitability-Framework.pdf&access_pid=73695.

- Jeremy Hudgens, “The Great Cookie Countdown: What’s Next For Advertising Without Third-Party Cookies?” March 5, 2020, https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesbusinessdevelopmentcouncil/2020/03/05/the-great-cookie-countdown-whats-next-for-advertising-without-third-party-cookies/?sh=5f657c0942cd.

- Kylee Lessard, “What Is Native Advertising? The 6 Universal Types & How To Use Them,” August 25, 2018, https://business.linkedin.com/marketing-solutions/blog/linkedin-b2b-marketing/2018/What-Is-Native-Advertising.

- Yan Cao, “We Are Calling Out Questionable College Advertising. Here’s How.” August 18, 2020, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/calling-questionable-college-advertising-heres/.