In November 2018, in a tragic scene that has by now become all too familiar, Copts converged on al-Amir Tadros Church in Minya, 150 miles south of Cairo on the banks of the Nile. They were there to bury seven victims of a militant attack on buses returning from an organized visit to the Monastery of Saint Samuel, a popular but remote pilgrimage site in the Minya governorate. During the funeral service, an officiating cleric began the pro forma practice of acknowledging and thanking various security and governorate officials for their assistance and efforts. The negative response to the recitation was audible: the grieving Copts could not cheer for a roll call of agencies that had failed them, yet again. In videos of that moment the unrest and disquiet can be seen and heard.1 The response illustrates the alienation experienced by Egyptian Christians in their interactions with the security state, a sector from which they are almost wholly excluded.

The exclusion and absence of Christians from the security sector is an exaggerated and critical example of a much broader phenomenon of underrepresentation of Copts within the Egyptian state and bureaucracy, particularly at more senior leadership levels. (Copts are generally understood to make up approximately 10 percent of Egypt’s population.)2 The causes of this exclusion reflect broader societal trends that have entrenched discrimination, bigotry, and mistrust—but the causes are also a function of the particularities of the security state itself and its unique evolution in modern Egypt.

In recent decades, the religious revivalism that has gripped Egypt and the broader Arab world has seen the gradual Islamization of public space and political life, further marginalizing Copts from those spheres. This trend has also created a cycle of withdrawal and self-selection in which Christians have retreated in response to observable increases in sectarianism and discrimination. In part, this is one broad aspect of the explanation for the absence of Christians from the security sector.

However, there are also other particular explanations that are unique to the institution of the military itself, an institution that has been central to political power in modern Egypt. First is the relatively recent Egyptianization of the military and military leadership in Egypt. With both Ottoman and British governance structures holding sway deep into the twentieth century, the composition of the military and its leadership was notable for the total absence of Egyptians in the military, and, later, their secondary role. As such, the Egyptian military tradition is of recent vintage and does not have deep historical roots. Importantly, Christian participation in the military remained weak during these early, formative years, when notions of citizenship were rudimentary and far from universally accepted.

Second, when the military effectively took power under the Free Officers in the Egyptian Revolution of 1952, the sociocultural milieu from which these junior officers emerged—one in which Christians were effectively unrepresented—understandably shaped their worldview and set the pattern for subsequent exclusionary and discriminatory practices. The rise of an Egyptianized and politicized military coincided with the broader setbacks to Christian participation in public and political life that began during the interwar period.

The accumulated history of those practices has now become firmly entrenched. It is then unsurprising in a country in which sectarian practices have reached such a stage that Christians are effectively excluded from participating in Egypt’s football academies and professional football league that similar and more serious forms of discrimination exist within the Egyptian state itself.3 The trajectory of exclusion from the security sector—military, state security, intelligence—is an important indicator of the sectarian divisions, bigotry, and mistrust that continue to define Egyptian society.4 Even more so than the broader bureaucracy, where discrimination is the default position, there are segments of the security state where Copts are not simply underrepresented but are wholly absent.

The impact of this form of discrimination and exclusion is profound. At a practical level, it arbitrarily caps the pool of qualified candidates, and limits exposure to and awareness of a swathe of Egypt’s citizenry. In this sense, it has also played a part in fueling and reinforcing the social segregation that typifies contemporary Egyptian society. That unnatural separation helps inculcate paternalistic and patronizing attitudes in which the state is tasked with dealing with and protecting a marginalized minority community that sits separate and apart from political and coercive power.

This marginalization is magnified in the Egyptian context because of the outsized role of the military and other organs of the security state in Egypt’s political life and society. Of course, in an authoritarian setting such as Egypt, the security state is often tasked with repressive and coercive actions. Noting the exclusion of Copts from such centers of power and authority is not to suggest that Christians also be allowed to play a part in the repressive architecture that undergirds authoritarian stability and sustainability. Instead, it is to note that exclusion from the most powerful and respected institutions of the state will necessarily limit the kinds of power that can be attained by Christians, and will inform popular perceptions regarding the nature of citizenship.

Much more profoundly, such exclusion has significant symbolic effects and has reinforced a sense of second-class citizenship for the country’s Christians. Copts are not direct participants in the defense of Egyptian national security, and are often not trusted with such portfolios. In a very real sense, participatory citizenship is diminished for Christians.

Beyond these practical impacts, and much more profoundly, such exclusion has significant symbolic effects and has reinforced a sense of second-class citizenship for the country’s Christians. Copts are not direct participants in the defense of Egyptian national security, and are often not trusted with such portfolios. In a very real sense, participatory citizenship is diminished for Christians. “It pushes you to feel disengaged from your country,” as one young Christian told a Guardian journalist in 2015, succinctly summarizing the corrosive impact of such forms of exclusion. “How could someone maintain his love for his country—and be passionate about building it—while at the same time he can’t be whatever he wants to be, whether a military commander or a police commander?”5

Egyptianizing the Military

The dynamic between foreign powers and the local citizenry has been a defining feature of Egyptian society for centuries, if not millennia. As historian Arthur Goldschidt, Jr. notes, “from 332 B.C. until 1952 non-Egyptians governed the land while Egyptians toiled to support them.”6 But that support was largely absent in the realm of the military. As such, the history of the Egyptian military as a fully Egyptian institution is a relatively recent one in historical terms. The brevity of that history of Egyptian participation has had impacts that remain with Egypt to the present.

That limited history, particularly during an earlier era when notions of citizenship were new and contested, created a brief and unfulfilled window for Christian inclusion in military leadership prior to the hardening and deepening of sectarian division and suspicion.

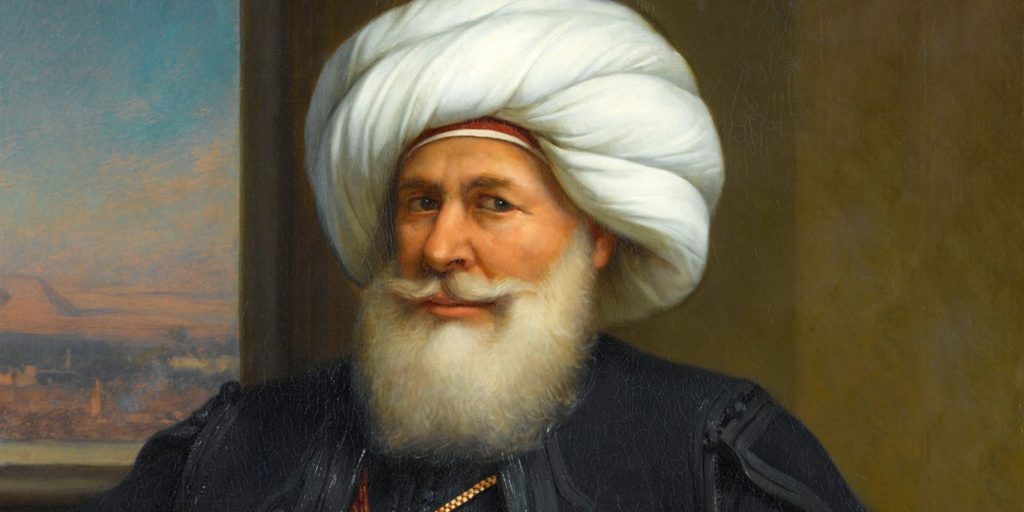

Goldschmidt points out that “in the late eighteenth century Egypt was a poor, isolated, and neglected Ottoman province.”7 In 1805, the rise to power of Muhammad Ali Pasha (r. 1805–48) marked a shift in Egyptian history with profound implications for the institutional infrastructure of the state. Muhammad Ali embarked on a vast program of modernization in Egypt, much of which centered on the military. Those efforts resulted in the creation of a “modern standing army that was disciplined, well trained and regularly paid,” in the words of the scholar Khaled Fahmy.8 Crucially, however, those efforts highlight the lengthy process of Egyptianization of the institution of the military, and the limited history of Egyptian participation at leadership levels. That limited history, particularly during an earlier era when notions of citizenship were new and contested, created a brief and unfulfilled window for Christian inclusion in military leadership prior to the hardening and deepening of sectarian division and suspicion.

Previously, the Egyptian military was constituted primarily of Mamluks, but Muhammad Ali looked toward the newly organized Ottoman and French armies as sources of inspiration for reform. First, he had to rid himself of the Mamluks, who “had effectively been the warlords of the country for centuries,” as Fahmy writes.9 Muhammad Ali killed many of them on March 1, 1811, during a festive ceremony in the Cairo Citadel to celebrate the appointment of his son, Tusun Pasha, to fight Wahhabi rebels in the Arabian Peninsula. Then, he sought to discipline his own Albanian troops by putting “their pay and expenses under an organized principle.”10 Having failed to impose order on his Albanian troops, however, during the conflict against the Wahhabis, “he sent wave after wave of them to face their destiny in the barren deserts of Arabia, thus effectively ridding himself of their nuisance.”11

Muhammad Ali’s original plan was to recruit Sudanese slaves into his army. Although nationalist historiography emphasizes his championing of the fellahin (the agricultural workers of Egypt), this was, in fact, an afterthought. In 1820, he dispatched two expeditions to Sudan, composed of Maghrebi and Egyptian bedouin and Turkish-speaking infantry and cavalry. However, he had problems securing the transportation of the Sudanese slaves to Egypt and also realized, as Fahmy writes, “that the army sent to Sudan was much larger than the number of slaves captured, which defeated the purpose for which it was sent in the first place.”12 Given that Turkish and Albanian soldiers were not accustomed to the climate in Sudan during their expeditions, he then thought to conscript the fellahin in order to relieve his own Turkish soldiers from these expeditions.

While largely Turkish officers and Arab and Sudanese soldiers were being trained, top officials were devising an organizational structure for the new army. They discussed the size and internal division of regiments, ratio of officers, ethnic composition of the officer corps, and pay of different ranks. Muhammad Ali insisted that fellahin would not be promoted beyond the rank of those commanding twenty-five soldiers. In other words, there was a low ceiling placed above the fellahin in the context of upward mobility within the military. The new Egyptian army’s victory against Wahhabis in Arabia; their ability to control a potentially volatile situation on March 22, 1824 following an explosion inside the Citadel; and their quelling of a rebellion that broke out in April 1824 over conscription and tax policies all convinced Muhammad Ali that universal conscription was the way forward. As Fahmy notes, “from that time onwards conscription waves frantically followed each other so that by the mid-1830s the number of conscripts had already reached 130,000”—2.6 percent of the population.13 Undoubtedly, this signaled a major step toward the Egyptianization of the Egyptian army.

Importantly, however, the beginnings of conscription did not impact the composition of the officer corps, which remained “ethnically and linguistically different from the overwhelming majority of the soldiery.”14

Muhammad Ali’s son, Ibrahim Pasha, generally followed this formula of having Turkish-speaking officers ruling over Arabic-speaking fellahin conscripts. These boundaries were very difficult to transcend. Egyptians were not promoted beyond the rank of captain and very few were even promoted to that rank at all. Even if the army was in short supply of Turkish officers, Muhammad Ali made clear to his son not to promote Egyptians to senior ranks.

In the 1850s, under Mohamed Sa’id Pasha (r. 1854–63), indigenous Egyptians were increasingly promoted within the bureaucracy and the military, and Sa’id Pasha began falling out with some of his Turkish-speaking civil bureaucrats. But his successor, Isma’il Pasha (r. 1863–79), reversed Sa’id Pasha’s pro-Egyptian policies by “reaffirming Ottoman-Egyptian dominance of the officer corps and the upper reaches of the civil bureaucracy.”15 In the period from 1858 to 1882, Ottomans and Circassians, as opposed to indigenous Egyptians, held a monopoly on high government posts and the officer corps in the military. Isma’il Pasha set up new military academies that almost exclusively recruited from the Ottoman nobility and Circassian nobles and gentry.16 Yet, purely because of the dramatic expansion of the military under Isma’il, there were many indigenous Egyptians who were able to make their way up the ranks into the officer corps.

Conscription and Nationalist Feelings

These changes were also having an impact on Christians. In 1855, Sa’id Pasha abolished the “jizya” (a tax levied on non-Muslims) and ordered that Copts be conscripted into the military.17 Even though Sa’id Pasha’s predecessor, Abbas I (r. 1849–54), had conscripted some Copts into the army, Sa’id Pasha’s abolishing of the jizya coupled with his continuation of Coptic conscription highlighted his efforts to dissolve religious communal boundaries.18 Despite this measured progress, there are historical accounts that suggest that during his brief period of rule, Abbas I had gone so far as to contemplate the wholesale resettlement of all Copts from Egypt to Sudan.19

In 1879, under Mohamed Tewfik Pasha (r. 1879–92), restrictions were lifted against Christians and Jews from riding horses and bearing arms.20 However, these measures did not signal equality between Copts and Muslims in Egypt. In fact, Sa’id Pasha refused to admit Copts to state schools, hindering them from joining their Muslim counterparts in the junior ranks of the officer corps. Only in 1867 were Copts in Egypt allowed to enter such schools following a decree from Ali Mubarak, a public works and education minister, and Isma’il Pasha; the decree opened state schools to all, regardless of religious affiliation.21

Sa’id Pasha refused to admit Copts to state schools, hindering them from joining their Muslim counterparts in the junior ranks of the officer corps. Only in 1867 were Copts in Egypt allowed to enter such schools following a decree from Ali Mubarak, a public works and education minister, and Isma’il Pasha.

The conscription of Copts into the military was met with a mixed response from the Coptic community. According to the scholar Muhammad Afifi, historical sources pertaining to the Coptic reaction to conscription are “inconsistent and contradictory.”22 Copts in Asyut protested the conscription, but it is unclear whether they were opposed to the conscription itself or the seemingly arbitrary nature of recruiting potential conscripts. Some Coptic leaders feared that conscription would expose Copts to pressures to convert to Islam, whereas other Coptic leaders faced pressure from wealthy Copts not to recruit their sons.23 Despite this movement toward equality of citizenship, many Copts viewed these changes with concern, as historian Paul Sedra has written, “that their traditional bargain with the state was void—that, though no longer required to pay the jizya, they faced conscription.”24 An arrangement was made between Copts and the government whereby Copts could be excused from military service in return for paying a new tax called the “bedel.”25

On the other hand, some sources indicate that the patriarch Kyrillos IV accepted the demands for conscription and requested “equal treatment between Copts and Muslims in appointments to high offices, as well as the promotion of Coptic conscripts to the officer corps.”26 Regardless of the exact motives, most historians agree that the conscription of Copts was met by general opposition, just as most Egyptians viewed conscription with a considerable degree of suspicion and reluctance.27 This understandable reticence affected levels of participation and perceptions regarding the desirability of career progression in the armed forces.

During the debt crisis of the 1870s, the military suffered from reductions and shrinkages. In 1879, the cabinet adopted recommendations of an investigatory commission on military affairs to reduce the size of the army from 90,000 to 36,000 soldiers. This included a reduction of the officer corps from 2,609 to 993. The social groups that stood to lose the most were therefore the Circassian junior officers and a small number of Egyptian junior officers of peasant background who had made their way up the military hierarchy.28 As a result, junior Egyptian officers faced exclusion from the officer corps.

At the same juncture, there is evidence that young Egyptian officers formed a secret society within the military as a result of an overall sentiment of discontent with the Ottoman and Circassian dominance of the officer corps. The young officers’ society drew its membership from ethnically Egyptian, Muslim, Arabic-speaking junior officers in the army. This nationalist agitation within the ranks of the junior officer corps began an important pattern that would come to be decisive in terms of promoting certain classes and milieus into national prominence. It is also instructive that, as the scholar Samuel Tadros has written, “Orabi Pasha, the military officer who emerged as the key figure in these years, managed to eclipse the civilians and ensure a military domination of the national struggle.”29

Some currents of Arab nationalism also fed the idea that Copts were not to be trusted. Following the Egyptian defeat in the Ethiopian–Egyptian war of 1874–76, Ethiopian forces couched their victory in religious and civilizational terms, claiming that Ethiopian Christians had successfully staved off an Islamic encroachment of Ethiopia.

Some currents of Arab nationalism also fed the idea that Copts were not to be trusted. Following the Egyptian defeat in the Ethiopian–Egyptian war of 1874–76, Ethiopian forces couched their victory in religious and civilizational terms, claiming that Ethiopian Christians had successfully staved off an Islamic encroachment of Ethiopia. Certain Arab nationalists took this at face value, viewing Egyptian Copts as possible traitors. For example, Adib Ishaq, the anti-imperialist Syrian Christian journalist writing from Egypt, argued that Copts supported Ethiopia against their own country in the conflict.30

This period of agitation coming on the heels of Egypt’s debt-induced economic distress paved the way for direct British intervention. Following the British invasion and occupation of 1882, the military was far more under the control of the British than the state bureaucracy. The top positions within the army were held by the British, and the military crisis of 1894 intensified their efforts to rid themselves of discontent within the army. As Robert Tignor notes, “Egyptian officers could hardly expect promotions unless they had demonstrated loyalty to British rule.”31 The British occupation of 1882 also marked the beginning of considerable change for the position of Copts in the military, with the removal of the bedel tax in 1909 and the introduction of universal military service for all males, regardless of religious affiliation.

While Copts had made gains in terms of appointments within the state as a result of previous reforms, many were dissatisfied with the British authorities, suspecting them of discriminating against their community when it came to high-level appointments, both in the bureaucracy and the military. This period also witnessed the intensification of nationalist politics and discourse, which inevitably touched on the Coptic question. That question was further aggravated by the assassination of Boutros Ghali in 1909 shortly after his appointment in 1908 as Egypt’s first Coptic prime minister. Copts’ place in the emerging nationalist debates about identity, and the issue of Coptic grievances, were revealing themselves as fraught political questions.

While a degree of nostalgia has defined the ways in which the nationalist struggle and the 1919 revolution have subsequently been portrayed and understood, it is undoubtedly the case that it marked a high point in sectarian relations and ushered in a period of unprecedented Coptic political participation.32 Copts played a pivotal role in the nationalist movement that spearheaded the 1919 Egyptian Revolution and the subsequent British recognition of Egyptian independence in 1922. However, Egypt’s brief liberal experiment also saw Copts used as a political prop in domestic political struggles against the Wafd Party, continuing discrimination in governmental appointments, and the rise of the Muslim Brotherhood and Islamist animus toward Christians in Egypt. These developments would be a precursor to the retreat of Christians from public life and the increasing social segregation among the sects.33

The Free Officers and the Copts

Disillusionment with Egypt’s liberal period provided the platform from which the Free Officers would base their push for power. As historian Zeinab Abul-Magd notes, the Egyptian Free Officers were distinct from other comparable regional coups during that era, because they were in temporary alliance with Islamist forces.34 Notably, they came from a specific social milieu; they were, she argues, “culturally conservative and internalized religious beliefs, which explains their initial openness to collaborate with the Muslim Brothers.”35 The composition of the young officer class had undergone a transformation since 1936, when Mostafa El-Nahas had expanded entrance opportunities to the Military Academy to a much wider swathe of Egyptians, where previously “earlier regulations had made the academy the fief of the sons of the wealthy.”36

The composition of the young officer class had undergone a transformation since 1936, when Mostafa El-Nahas had expanded entrance opportunities to the Military Academy to a much wider swathe of Egyptians.

Signed in 1936, the Anglo–Egyptian Treaty granted Egyptian control over the military for the first time since 1882. That year witnessed the opening of the Royal Military Academy to a much more diverse pool of soldiers and officers, largely from middle and lower-middle classes.37 In fact, this development was part of a wider expansion of the military that saw its officer corps more than double in one year.38 As the academic Charles Tripp notes, “a noticeable feature of this new intake was the substantial proportion of officer cadets from considerably more modest backgrounds than had hitherto been the case.”39 As a result of existing trends, however, these changes did not significantly alter the trajectory of Christian inclusion and participation. Further, many aspects of the Egyptian military were still far from being fully independent. The British still retained control over training officers, dictating the level of arms supplies, and mandating that Egyptian officers seeking advanced training attend British military academies.

While this period was notable for its increased recruitment and diversity of officers, it also disrupted existing patterns of patronage and created the conditions for new political networks to emerge within the military. Far from being a wholly meritocratic institution, “without patronage it was unlikely that they [poorer officers] would receive equal treatment with their better connected contemporaries.”40 Lacking family connections, many of the new Egyptian officers entered into patronage networks headed by figures such as Aly Maher Pasha (sometimes styled “Ali Mahir”), who sought to create political subgroupings within the military that were exclusively loyal to the king. However, as Tripp has shown, the shifting politics of the 1930s and 1940s often caused these networks to take on their own direction, independent of their patron’s political ambitions.41 The academic Ahmed Hashim argues that many of these young officers viewed the Egyptian monarchy as corrupt and subservient to the British, and thus often flirted with existing ideological countercurrents such as liberal constitutionalism, Marxism, Islamism, and fascism.42 In fact, many of the Free Officers who seized power in 1952, as Tripp writes, “obtained their political initiation within the army through Ali Mahir’s secret Officers’ Organisation.”43

The loosening of British control over the army, and its ensuing reform, coupled with the changing class composition of the officer corps, created the basis for new modes of political organization within the military. Conflicts often took place between the Wafd Party and the palace over military influence, but the overwhelming result of these struggles was to cement the role of the military as a dominant force in Egyptian politics.

The Free Officers held a relatively ambivalent view toward Coptic Christians in Egypt, and their leader, Gamal Abdel Nasser himself, according to Tadros, “did not hold any personal animosity toward Christians.”44 On the one hand, Copts did not present themselves as a unified political bloc that would threaten the power of the Free Officers. Yet Copts were severely underrepresented in the officer corps because of the long-standing historical reasons discussed above. Therefore, they were also underrepresented in revolutionary bodies. For example, the Revolutionary Command Council that ruled Egypt following the ouster of King Farouk (who reigned 1936–52) had no Coptic members.45 According to historian J. D. Pennington, official sources differ as to whether there was even one Copt in the Free Officers movement at all.46 In the new regime, Copts held hardly any high-ranking civilian posts, with Major General Kamal Henry Abadeir, who briefly served as minister of communications in the 1960s, being a rare exception.47

As Pennington argues, after the rise of the Free Officers, the position of Copts within Egyptian society was under some stress: “The Copts suffered a loss of prestige after the Revolution. They were, in the eyes of many Muslims, associated with the previous regime. The stress of a succession of wars and confrontations with Israel and the West increased the sense in some quarters that they were an alien, potentially hostile minority. The departure of smaller non-Muslim minorities, Jews, Greeks and Western Europeans, left them potentially an exposed target.”48

As a matter of representation, the government generally appointed one Coptic minister in every cabinet. However, the top positions in the state apparatus, bureaucracy, and especially the Egyptian military excluded Copts.

The underrepresentation of Copts in the wider public sphere stemmed from a combination of economic and political contingencies. In 1922, politicians debated the idea of reserving seats for Copts in the National Assembly. However, this was struck down following intense pushback by those who argued that the Egyptian Coptic population must not be perceived as a “minority,” but, rather, as part and parcel of the Egyptian social fabric. The more open politics of the interwar era and the fact that there were many wealthy, land-owning Copts in the pre-1952 period ensured their representation in this body. However, by 1957, following the first election during the revolutionary period, no Copts were elected. To avoid such conspicuous optics, Nasser, who assumed the presidency in 1954, engineered a series of political arrangements during the next election and the subsequent assemblies, whereby a certain number of Copts would be part of the National Assembly.49

This change in Coptic representation can be explained by two factors. First, the underrepresentation of Copts in the military, and specifically the officer corps, naturally led to the underrepresentation of Copts in government positions in the new military dictatorship—a form of path dependence. Second, the economic changes enacted under Nasser’s rule had severely diminished the influence of wealthy Copts in the Egyptian public sphere. Wealthy landlords were stripped of much of their power as a result of Nasser’s program of land reform, even if certain Coptic peasants benefited. As the writer Tarek Osman notes, between 1880 and 1953, more than forty of the largest one hundred land-holding families were Christian.50 The nationalization of large companies such as the Magar and Morgan bus companies and the Banque du Caire, all owned by Copts, undoubtedly contributed to the diminishing political relevance of Copts in Egyptian society.

Copts also suffered as a result of some of the government’s political decisions. Institutions such as the Ministry of Finance or teaching bodies of medical facilities witnessed a dramatic reduction in the recruitment of Copts. In secular, leftist organizations, Copts were likely overrepresented and therefore suffered under Nasser’s crackdown on the wider Egyptian left. According to Milad Hanna, 30 percent of leftists arrested under Nasser were Copts. All of these changes contributed to the increase in emigration of Copts to the United States, Canada, and Australia beginning in the 1960s.

These changes should not be interpreted as a concerted effort by the Free Officers to strip all Copts of their power, but they certainly reflected a lack of concern regarding inclusion and equality.

These changes should not be interpreted as a concerted effort by the Free Officers to strip all Copts of their power, but they certainly reflected a lack of concern regarding inclusion and equality. As noted, Coptic peasants generally benefited from the program of land reform. Additionally, Nasser increased the power of the Coptic patriarch by abolishing the “Maglis al-Milli,” a body that had represented lay Copts. As such, he eliminated the power of an institution of the ancient regime and created a new arrangement whereby Coptic representation fell within the confines of the Church hierarchy. As Pennington puts it, the government “fell back on the ancient practice of dealing with the Patriarchate as the representative of Coptic opinion.”51

Despite the beginnings of revisionist accounts of modern Coptic history, there is a great deal of unanimity on the diminution of the role of Coptic elites, who had played a central role in national affairs and political life in the interwar period.52 This had a profound impact on the role of the church, with the institutional church emerging as an overtly political actor, often serving as the communal interface between the state and Christians.

The Enduring Effects of Discrimination

The patterns of public and political life for Christians established by Nasser would prove durable. Under Anwar Sadat (president 1970–81), the exclusion of Copts from the Egyptian military continued, with the notable exception of General Fouad Aziz Ghali, whose unique ascension highlighted the rarity of Coptic participation at the highest levels of military leadership. Sadat appointed Ghali as the commander of the Second Army near the end of the October 1973 war, during the early stages of which he had led the Eighteenth Infantry Division’s famous crossing of the Suez Canal and assault on the Bar-Lev Line.53 In leading the crossing, Ghali was entrusted with a critical military role that was at the center of Egypt’s overall war-fighting strategy.54 Ghali’s ascent within the senior ranks of the armed forces was even more notable in light of Sadat’s domestic political positioning and his cultivation of Islamist forces as a counterweight to old-guard Nasserists who remained wary and suspicious of Sadat. Ghali’s unique career continued when he was appointed governor of South Sinai governorate in 1980, a position he maintained when Sinai was returned to Egypt in 1982.55

Also notable during the Sadat era was the further deterioration of sectarian relations and the increase in friction and violence directed against Copts. As the scholar Laure Guirguis argues, “from the 1970s, attacks on Christians became a recurrent feature of Egyptian society.”56 The outbreak of communal violence directed against Copts in Khanka in November 1972 was emblematic of this phenomenon, often linked to attempted construction of churches, and was a harbinger of future sectarian conflict. The recurring pattern of this kind of sectarian violence and the lack of formal accountability or criminal justice processes to deal with it also highlights the ways in which the lack of inclusion of Christians within the security state affects the approach adopted by the state toward sectarian issues. Sadat’s own personal feud with Shenouda III (Coptic patriarch 1971–2012), which resulted in Sadat’s attempting to strip the religious leader of his clerical authority and banishing him to confinement at the St. Bishoy Monastery, added a further layer of strain to the already tense sectarian environment.

Overlaying these developments was the religious revivalism that would shape the region’s political trajectory for decades to come. In the wake of the serial failures of secular Arab nationalism, deteriorating sectarian relations and increased frictions were emblematic of the period. While the undercurrents and roots of Islamism were long-standing, the post-1967 era of Egyptian and Arab politics witnessed the ascendance of various kinds of Islamism as programmatic political movements. This revivalism has altered the social fabric of Egyptian society and further undermined the position of Christians.

More broadly, the Sadat era marked a continuation of sectarian hierarchies established under Nasser, as well as the long-standing de facto limits on representation and advancement. The noteworthy career of the diplomat Boutros Boutros-Ghali exemplifies the barriers to Coptic advancement. Boutros-Ghali, despite later being appointed as the secretary-general of the United Nations, was unable to advance to the highest possible position within his own state when Sadat balked at naming him Egypt’s foreign minister. Reflecting on his tenure as acting foreign minister, Boutros-Ghali wrote:

I had hoped that the Egyptian leadership would realize that I should become foreign minister and lead Egyptian diplomacy during this delicate period. But my hope was not realistic, because recognition in politics was a matter of internal balances, including religious currents. Realizing this, I blamed myself for having been unrealistic. I knew that Sadat’s hesitation was partly a result of the attack on me and my family by Arab media. For me, it made no practical difference whether or not I bore the title of foreign minister. The job was the same. But I was pained by the increasingly intolerant religious current in Egypt, a sign of intellectual regression. Abbas Hilmi Pasha, khedive of Egypt, had not hesitated to appoint my grandfather Boutros Ghali foreign minister and then prime minister nearly a century ago. Half a century ago a series of Christian foreign ministers had served in the first Wafdist cabinet after the 1919 revolution. Saad Zaghlul, with the approval of King Fuad, had not hesitated to appoint my uncle Wasif Boutros-Ghali foreign minister. But today, in the fourth quarter of the twentieth century, Sadat hesitated to appoint a non-Muslim as foreign minister of Egypt.57

Under Hosni Mubarak (president 1981–2011), this exclusionary trend continued and coincided with the rise of organized Islamist militancy and violence targeting Copts. The Mubarak era was marked by the concerted attempts to neuter Islamist trends through cooptation. The result of these efforts was the further Islamization of Egyptian public life.58

Within the state, cabinet-level appointments followed the established practice of rigid tokenism, whereby Copts would generally be given two ministries, often of lesser importance.59 In the latter years of the Mubarak regime, Youssef Boutros-Ghali served as minister of finance from 2004 until the uprising in 2011. Although he filled a position in a lesser ministerial role often reserved for a Copt, Maged George, a former military officer, served as minister of state for environmental affairs from 2004 to 2011. Patterns within the security establishment remained stable as well. As in previous eras, there were almost no high-ranking Copts in the military, state security, and intelligence services.60 A notable exception to that state of affairs was the 2006 appointment of Magdy Ayoub, a police general, as governor of Qina governorate.61

Continued Exclusion

Research and documentation of issues related to Egypt’s Christians is challenging. As Sedra argues, “the near-total absence of reliable statistical data on the Coptic community and the government-imposed obstacles to research in the field, both born of political sensitivities surrounding the topic, have scarcely helped researchers develop a more nuanced view of the community, of its internal dynamics, and of the great cleavages that divide it.”62 The intersection of that type of research with the security state renders documentation even more challenging. Even more so than with respect to other organs of the Egyptian state and bureaucracy, the security state and its inner workings remain largely opaque. This lack of transparency in connection to the military and the security sector is a design feature of Egyptian authoritarianism. As the writer Lars Gunnar Christiansen rightly argues, “accurate facts concerning the [Egyptian armed forces’] materiel and personnel are hard to come by. It is difficult to be accurate about the number of Coptic officers and conscripts serving in the Egyptian military.”63 In this sense, documentation of discrimination is a difficult task despite the quite obvious manifestations of its existence. Systematic documentation in this instance remains impossible, but through a combination of publicly available information and interviews, it is possible to go beyond mere anecdote and conjecture.

The most visible public evidence is the composition of senior leadership within the armed forces. Public exposure to the Egyptian military leadership has increased significantly since the January 2011 uprising, which resulted in the ouster of Mubarak and initiated a much more public and political role for the military and its leadership. Previously, the longtime minister of defense, Mohamed Hussein Tantawi, was a recognizable but largely understated public figure; other senior military figures were largely unknown to the Egyptian public. As part of their expanded public profile following the January 2011 uprising, which included holding interim executive authority for nearly a year and a half, the senior military leaders of the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) became public figures. The composition of the SCAF became a much more widely circulated piece of public information. Conspicuous at that time and the years since has been the lack of Christian representation at the highest levels of the Egyptian armed forces. Since the uprising and until the present, there have been no Copts on the SCAF.

This absence is notable, as Abdel Fattah el-Sisi has sought to cultivate the Christian community for electoral and political purposes, and has also made several symbolic gestures in that vein, such as visiting the Coptic cathedral on important church feasts and supporting construction of the region’s largest cathedral in the country’s new administrative capital.64 On his first such visit, which was the first of its kind by an Egyptian president, Sisi declared that “it is not right to call each other anything but ‘the Egyptians.’ We must only be Egyptians!”65 Sisi has also suggested that he would address the long-standing grievances related to church construction and repairs, and the onerous and discriminatory regulations that have effectively crippled the ability of many Christian communities to build new churches. In late 2018, Sisi also announced the establishment of the Supreme Committee to Combat Sectarianism.66 This series of symbolic gestures has come against the backdrop of persistent Islamist violence targeting Copts. More importantly, as visibly demonstrated by senior military appointments, the approach of the state toward Copts has remained constant and disappointing despite occasional rhetorical efforts to suggest concern over Christian complaints and grievances.

Abdel Fattah el-Sisi has sought to cultivate the Christian community for electoral and political purposes, but the approach of the state toward Copts has remained constant and disappointing despite the rhetoric.

At a lower level, the Military Academy, as Egypt’s gateway to careers in the security state, continues to display a persistent underrepresentation of Christians in its ranks. In a discussion with a former military officer and graduate of the Military Academy, the former officer said that he knew two Copts in the Military Academy and one in the Naval Academy.67 More broadly, he estimated that during his time at the Military Academy there were around eight to ten Copts out of some eight hundred students, and possibly one Copt in the Air Force Academy.68 Although he stated that there “was no existing quota,” he suggested that Christians prefer admission in other disciplines, such as medicine and engineering, which offer social prestige and a pathway for advancement that was not necessarily linked to the state.69 Reflecting on these low numbers of participation in the military, he went on to suggest that dominant attitudes at the Military Academy and the security establishment more broadly hindered inclusion of Christians.70 He concluded by arguing that “the mentality of the security man is that they can’t be fully trusted.”71

In recent years, representatives of the Military Academy have occasionally discussed the question of demographic representation and discrimination. In an interview in 2012, the head of the Military Academy, Brigadier General ’Esmat Murad, sought to deflect potential criticism of the demographic composition of the academy, in effect implicitly recognizing its lack of demographic balance. According to a media report, Murad argued, in the clichéd nationalistic manner often seen when the state broaches topics related to sectarianism and discrimination, that “the academy does not differentiate among any of the students that come to it and there is no favoring some groups over others, under any political, religious, or ethnic categorization.”72 He explained that “the sons of sheikhs and priests and the sons of the rich and the poor enter the Military Academy.”73 He went on to say that this nondiscriminatory approach was how the Military Academy had been for the two hundred years since its establishment.74

The following year, Murad publicly addressed in greater detail the demographics of the incoming students at the Military Academy and other military institutions. He noted that there were 2,510 incoming students across all the military institutions, including 82 women and 32 Christians.75 While this counts as a rare moment of some transparency on issues usually unaddressed, the underlying demographic underrepresentation at an institution that serves as the entry point for future military leadership is stark. In seeking to display the school’s tolerance to religious difference, he stated that upon reporting for admission Muslim students would receive “a prayer rug and a Quran,” and that Christian students would receive a Bible and would have a priest to conduct services each Sunday.76

Murad’s successor as the head of the Military Academy, Brigadier General Gamal Abu Ismail, struck similar themes when discussing the issue of admissions, while avoiding any specificity regarding incoming demographics, arguing simply that “the academy accepts Egyptian youth from different groups without favoritism.”77

Even more so than the military, the pattern of discrimination is heightened in the realm of the State Security Investigations Agency (renamed the National Security Agency in 2011) and the intelligence services. Writing in 1982, Pennington argued that “some sensitive government departments—the General Intelligence Service for example—appear to be totally closed to Copts on the ground that they could be a security risk.” He goes on to note that while Copts are represented in the armed forces, although at less than proportional numbers within the ranks of the officers, they are not found in military intelligence.78 Tadros has similarly argued that discrimination and exclusion is so pervasive that “no single Copt is allowed in the state security or intelligence services.”79

While the exact parameters cited by Tadros are of course difficult if not impossible to document, at the very least they reflect established perceptions. In a discussion with a senior Coptic cleric, the cleric stated that in his experience and to his knowledge, he had never been exposed to or heard of a Copt serving in any kind of intelligence-related position.80 He argued that this was tantamount to state policy and was a function of the marginalization and distrust of Copts and a view toward Christians as less than full and equal citizens.81 He went on to argue that this discriminatory mindset created a “total glass ceiling.”82

When faced with a question about Christian participation in the intelligence services, a former senior intelligence official would not confirm or deny that there were no Christians whatsoever serving in such posts, and that Copts were effectively barred from such sensitive national security positions.83 Instead, while avoiding such a stark admission, the former official conceded that there had been unfortunate discrimination in the past and that this had reinforced popular but not wholly accurate beliefs about enforced exclusion. He went on to say that this pattern of discrimination and formation of perceptions had spurred Copts to eschew attempts at joining national security institutions, such as the General Intelligence Services.84 While this defensive approach to the issue does not resolve the question of categorical exclusion from certain institutions, it is nonetheless remarkable to hear even this sort of limited admission that gives credence to the underlying problem.

Mistrust and Marginalization

Lars Gunnar Christiansen has described the historic role of the Egyptian armed forces as “the spearhead in Egyptian nation-building, as many national institutions were built around it, and the [Egyptian armed forces] frequently use national unity rhetoric in public media.”85 There are exceedingly small numbers of Christians in leadership positions within the institution, which very clearly suggests that “it does not sufficiently represent the religious diversity of Egyptian society.”86 Exclusion or underrepresentation from an institution that has been at the center of Egyptian public life for decades has had profound effects on the ability of Christians to reach certain positions of authority, but has also undermined the equality of citizenship for Copts. Absence has furthered suspicions about the ultimate loyalty and patriotism of Christians.

The effects of exclusion and underrepresentation are clear in a country in which the armed forces and the security sector have either dominated modern political life or, at other junctures, occupied a privileged and central position within the state. Those effects could be seen in the tragic events that have come to be referred to as the Maspero Massacre of October 2011, when mostly Christian protesters who had mobilized in Cairo in the wake of an incident of sectarian violence in Upper Egypt were attacked with live ammunition and run over by armed personnel carriers by Egyptian military forces, resulting in 28 deaths and 212 injured. Beyond the horrific violence meted out against the protesters, the attack was accompanied by vicious sectarian incitement and propaganda in various state media organs.

The effects of exclusion and underrepresentation are clear in a country in which the armed forces and the security sector have either dominated modern political life or, at other junctures, occupied a privileged and central position within the state.

Beyond the path dependence attendant to the specific evolution of national security bodies and institutions, the mistrust and marginalization that has typified the experience of Christians within the security state is the product of a specific form of mistrust and suspicion. That mistrust and suspicion has been aggravated in recent decades by the rise of various forms of Islamist supremacist movements, from mainstream organizations such as the Muslim Brotherhood to more violent and militant groups that have undertaken armed attacks against Christians. The deepening of sectarian sentiment and the furthering of social segregation among sects has hardened the divisions and misperceptions that now animate and typify sectarian relations. All of these factors have inhibited the deepening of the incomplete and still contested notions of citizenship in Egypt.

However, the roots of mistrust can also be found in the intersection of geopolitics and religion in the form of both imperialism and great power politics and influence. As the scholar Kenneth Cragg argued in 1991 about the increasing European attention to Egypt, “the growing involvement of Europe’s politics, personnel, and—we must add—priests in Egypt’s story had repercussions for Coptic hopes and circumspection.”87

At times, the colonial attitude toward Egyptians was even-handed in its disdain, which somewhat disguised colonialism’s effect on the growth of religious prejudice in the country. Lord Cromer, the British colonial administrator of Egypt from 1883 to 1907, famously dismissed the notion that Copts should be approached differently than Muslims or should be accorded any special treatment: “For the purposes of broad generalization, the only difference between the Copt and the Muslim is that the former is an Egyptian who worships in a Christian Church, whilst the latter is an Egyptian who worships in a Mohammedan Mosque.”88

Despite this dismissive attitude, the fact of the Christian nature of the imperial presence in Egypt and the Arab world bred suspicion that Arab Christians were favored by or sympathetic with the colonial projects that denied the region dignity and independence. These insidious sentiments have continued to color perceptions of Copts and have formed the basis of discriminatory attitudes that have framed Christians as less than fully patriotic or loyal to Egypt and its national security. In a speech delivered to the Egyptian parliament in May 1980, as Tadros writes, Sadat “accused the pope [of the Coptic Church] of seeking to establish a Christian state in the south of Egypt in Asyut. He decried what he called the church’s attempt to be a state within a state, and accused Copts of aiming to provoke foreign powers against Egypt and of receiving weapons and training from the Phalangists in Lebanon.”89

In more recent decades, these suspicions have been further inflamed by the rise of a Coptic diaspora and activism in the West.90 The instrumentalization of the Coptic issue among certain segments of U.S. politics and the rise and mainstreaming of anti-Muslim bigotry have at times provided a platform to undermine legitimate Coptic grievances by linking them with the suspect intentions of the United States and the West. It has also triggered a virulent and at times slanderous reaction in the Egyptian press, with accusations of traitorous behavior and intent.91 While such barbs are specifically aimed at the diaspora and its political activities abroad, this discourse of delegitimization has necessarily affected perceptions and attitudes toward Christians.

The sum total of this history is discrimination and distrust. Exclusion has fed the cycle of marginalization and retreat, and those patterns endure despite lofty proclamations of national unity and equality.

The sum total of this history is discrimination and distrust. Exclusion has fed the cycle of marginalization and retreat, and those patterns endure despite lofty proclamations of national unity and equality. Citizenship in Egypt remains truncated and incomplete for most at a time of resurgent authoritarianism and ferocious and heavy-handed repression. Nonetheless, particular forms of discriminatory behavior continue to affect Copts in specific ways, and the lack of inclusion of Copts within the security state is a clear testament to the durability of sectarian attitudes that undergird and animate such bias.

This report is part of Citizenship and Its Discontents: The Struggle for Rights, Pluralism, and Inclusion in the Middle East, a TCF project supported by the Henry Luce Foundation.

Cover Photo: A view as an Egyptian Army soldiers ride camels in the desert of Aswan, Egypt. Source: Ivan Dmitri/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Notes

- See the Twitter thread posted by Ibrahim Halawi on November 2–3, 2018, https://twitter.com/Ibrahimhalawi/status/1058714600101892096?s=20.

- There is some uncertainty with respect to the proportion of Christians in Egypt. Official governmental statistics uniformly refer to Copts as composing 6 percent of Egypt’s total population. While some church and lay leaders refer to much higher numbers, 10 percent is the most commonly used figure in news coverage of Egypt, although the lack of demographic grounding renders all of these estimates less than certain. See Michael Suh, “How Many Christians are there in Egypt?,” Pew Research Center, February 16, 2011, https://www.pewresearch.org/2011/02/16/how-many-christians-are-there-in-egypt/. Egypt’s fourteenth national census, conducted by the Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics and made available in September 2017, did not publicly provide a separate breakdown of data for religion. See “Infographic: Facts and Figures from CAPMAS’ 2017 Census,” Mada Masr, October 1, 2017, https://madamasr.com/en/2017/10/01/news/u/infographic-facts-and-figures-from-capmas-2017-census/.

- Mai Shams El Din, “Copts and Egypt’s National Game: We’ll Call You Back Later,” Mada Masr, July 20, 2017, https://madamasr.com/en/2017/07/20/feature/society/copts-and-egypts-national-game-well-call-you-back-later/.

- Although Copts are also underrepresented within the ranks of the police, there are greater numbers of Christians within the police force, save for the most sensitive positions within the Ministry of Interior, such as the National Security Agency, formerly known as State Security Investigations Agency, where Christian exclusion remains total.

- Jared Malsin, “Christians Under Pressure: From Bigotry at School to Imprisonment and Murder, Egypt: ‘It Pushes You to Feel Disengaged,’” Guardian, July 27, 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/jul/27/christians-under-pressure-bigotry-school-imprisonment-murder.

- Arthur Goldschmidt, Jr., Modern Egypt: The Formation of a Nation-State (London: Hachette, 1988), 5.

- Goldschmidt, Modern Egypt, 13.

- Khaled Fahmy, All the Pasha’s Men: Muhammad Ali, His Army and the Making of Modern Egypt (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 77.

- Fahmy, All the Pasha’s Men, 82.

- Fahmy, All the Pasha’s Men, 85.

- Fahmy, All the Pasha’s Men, 86.

- Fahmy, All the Pasha’s Men, 88.

- Fahmy, All the Pasha’s Men, 96.

- Fahmy, All the Pasha’s Men, 50.

- Juan Cole, Colonialism and Revolution in the Middle East: Social and Cultural Origins of Egypt’s ‘Urabi Movement (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992), 33.

- Cole, Colonialism and Revolution in the Middle East, 102.

- Muhammad Afifi, “The State and the Church in Nineteenth-Century Egypt,” Welt des Islams 39 (1999): 282.

- Donald Malcolm Reid, Whose Pharaohs?: Archaeology, Museums, and Egyptian National Identity from Napoleon to World War I (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003), 261.

- Samuel Tadros, Motherland Lost: The Egyptian and Coptic Quest for Modernity (Stanford, CA: Hoover Press, 2013), 76.

- Rachel Scott, The Challenge of Political Islam: Non-Muslims and the Egyptian State (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2010), 38.

- Reid, Whose Pharaohs?, 261.

- Afifi, “The State and the Church,” 283.

- Afifi, “The State and the Church in Nineteenth-Century Egypt,” 283.

- Sedra, “Class Cleavages and Ethnic Conflict: Coptic Christian Communities in Modern Egyptian Politics,” Islam and Christian-Muslim Relations 10, no. 2 (1999): 225.

- Lars Gunnar Christiansen, “Custodians of Social Peace or Contenders in a Popularity Contest? The Egyptian Armed Forces and Egypt’s Coptic Christians,” CMI Working Paper no. 4, 2015, 9.

- Afifi, “The State and the Church in Nineteenth-Century Egypt,” 283.

- Tadros, Motherland Lost, 83.

- Cole, Colonialism and Revolution in the Middle East, 102.

- Tadros, Motherland Lost, 109.

- Cole, Colonialism and Revolution in the Middle East, 145.

- Robert Tignor, Modernization and British Colonial Rule in Egypt, 1882–1914 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1966), 384.

- Samuel Tadros ascribes much of this improvement in sectarian relations to Sa’ad Zaghlul, the leader of the nationalist movement. Tadros, Motherland Lost, 134.

- Laure Guirguis, Copts and the Security State: Violence, Coercion, and Sectarianism in Contemporary Egypt (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2016), 57.

- Zeinab Abul-Magd, Militarizing the Nation: The Army, Business, and Revolution in Egypt (New York: Columbia University Press, 2017), 41.

- Abul-Magd, Militarizing the Nation, 41.

- Anouar Abdel-Malek, Egypt: Military Society: The Army Regime, the Left, and Social Change under Nasser (New York: Random House, 1968), 44.

- Ahmed Hashim, “The Egyptian Military Part One: From the Ottomans through Sadat,” Middle East Policy 18, no. 3 (2011): 66.

- Hashim, “The Egyptian Military,” 66.

- Charles Tripp, “Ali Mahir and the Politics of the Egyptian Army, 1936–1942,” in Contemporary Egypt: through Egyptian Eyes, ed. Tripp (Abingdon, UK: Routledge 2002), 47.

- Tripp, “Ali Mahir and the Politics of the Egyptian Army,” 56.

- Tripp, “Ali Mahir and the Politics of the Egyptian Army,” 66.

- Hashim, “The Egyptian Military,” 66.

- Tripp, “Ali Mahir and the Politics of the Egyptian Army,” 66.

- Tadros, Motherland Lost, 169.

- J.D. Pennington, “The Copts in Modern Egypt,” Middle Eastern Studies 18, no.2 (1982): 163–64.

- Pennington, “The Copts in Modern Egypt,” 164.

- Pennington, “The Copts in Modern Egypt,” 164.

- Pennington, “The Copts in Modern Egypt,” 165.

- Pennington, “The Copts in Modern Egypt,” 164.

- Osman, Egypt on the Brink: From Nasser to the Muslim Brotherhood (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013), 165.

- Pennington, “The Copts in Modern Egypt,” 165.

- Paul Sedra, “Writing the History of Modern Copts: From Victims and Symbols to Actors,” History Compass 7, no.3 (2009): 1057.

- Quoted in Christiansen, “Custodians of Social Peace,” 12.

- In 1978, Ghali was appointed chairman of the Armed Forces’ Organization and Management Authority; a year later, he was appointed assistant to the minister of defense. Galal Nassar, “A Hero Bid Farewell: Fouad Aziz Ghali (1927–2000),” Al-Ahram Weekly, January 13–19, 2000, http://weekly.ahram.org.eg/Archive/2000/464/eg7.htm.

- In news accounts of the ceremonies marking the return of Sinai, Ghali is described as weeping “as he raised the red, white, and black Egyptian flag at Rafah.” Maurice Guindi, “Israel Returns Sinai to Egypt,” UPI, April 25, 1982, https://www.upi.com/Archives/1982/04/25/Israel-returns-Sinai-to-Egypt/1136388558800/.

- Guirguis, Copts and the Security State, 17.

- Boutros-Ghali, Egypt’s Road to Jerusalem: A Diplomat’s Story of the Struggle for Peace in the Middle East (New York: Random House, 1997), 188.

- As I have noted elsewhere, the steady Islamization of society and public life had tangible outcomes ranging from the rising vehemence and ubiquity of sectarian hatred and polarization to the increasingly narrow bounds of intellectual discourse to the policing of blasphemous thought and Islamization of the legal system. See Hanna, “God and State in Egypt,” World Policy Journal (Summer 2014): 65.

- For the purposes of disclosure, the author’s great aunt, Venice Kamel Gouda, served as the minister of state for scientific research from 1993 to 1997.

- Scott, The Challenge of Political Islam, 83.

- Following the uprising and the formation of a government under Prime Minister Essam Sharaf, Ayoub was succeeded by General Emad Mikhail, a Copt who had previously served as the deputy head of Central Security in Giza. Mariz Tadros, “Egyptian Democracy and the Sectarian Litmus Test,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, May 11, 2011, https://carnegieendowment.org/sada/43944.

- Sedra, “Class Cleavages and Ethnic conflict,” 220.

- Christiansen, “Custodians of Social Peace,” 13.

- See David D. Kirkpatrick and Merna Thomas, “Egyptian Leader Visits Coptic Christmas Eve Service,” New York Times, January 6, 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/01/07/world/middleeast/egyptian-leader-visits-coptic-christmas-eve-service.html. See also “Egypt Opens Middle East’s Biggest Cathedral near Cairo,” BBC News, January 7, 2019, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-46775842.

- Kirkpatrick and Thomas, “Egyptian Leader Visits Coptic Christmas Eve Service.”

- Timothy Kaldas, “Egypt’s Sectarian Committee to Combat Sectarianism,” Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy, January 28, 2019, https://timep.org/commentary/analysis/copts-church-and-state-egypts-christians-frustrated-with-lack-of-protection/.

- Former military officer, interview with the author, February 2019.

- Former military officer, interview.

- Former military officer, interview.

- Former military officer, interview.

- Former military officer, interview.

- Maha Salem, “Director of the Military Academy…” (Arabic), Al-Ahram, November 7, 2012, http://gate.ahram.org.eg/News/269432.aspx.

- Salem, “Director of the Military Academy.”

- Salem, “Director of the Military Academy.”

- Mohamed Ahmed Tantawi, “Sisi Certifies the Results of the Military Academies and Institutes …” (Arabic), Youm 7, November 19, 2013, https://www.youm7.com/story/2013/11/19/السيسى-يصدق-على-نتيجة-الكليات-والمعاهد-العسكرية-قبول-2510-طالبا/1352694.

- Tantawi, “Sisi Certifies.”

- Ayman Ramadan, “In a Video: Director of the Military Academy …” (Arabic), Youm 7, August 21, 2017, https://www.youm7.com/story/2017/8/21/بالفيديو-مدير-الكلية-الحربية-لامكان-للواسطة-والأساس-فى-القبول-نتائج/3379304.

- Pennington, “The Copts in Modern Egypt,” 169.

- Samuel Tadros, “The Actual War on Christians: Egypt’s Copts Are under Attack,” Atlantic, December 17, 2016, https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2016/12/egypt-copts-muslim-christian-isis/511007/.

- Senior Coptic cleric, interview with the author, March 8, 2019

- Senior Coptic cleric, interview

- Senior Coptic cleric, interview.

- Former senior Egyptian intelligence official, interview with the author, November 2018.

- Former senior Egyptian intelligence official, interview.

- Christiansen, “Custodians of Social Peace,” 3.

- Christiansen, “Custodians of Social Peace,” 3.

- Kenneth Cragg, The Arab Christian: A History in the Middle East (Louisville, KY: Westminster/John Knox Press, 1991), 187.

- As quoted in Tadros, “The Actual War on Christians.”

- Tadros, Motherland Lost, 188.

- Michael Wahid Hanna, “With Friends Like These: Coptic Activism in the Diaspora,” Middle East Report 267 (Summer 2013): 267.

- Elizabeth Iskander, Sectarian Conflict in Egypt: Coptic Media, Identity and Representation (New York: Routledge, 2012), 34.