If you are having trouble accessing the interactive map on mobile, click here.

In just over 100 days—on September 30, 2023—child care for millions of children and families nationwide will begin to disappear, with dire consequences for children, families’ earnings, and state economies.

In the first-ever economic analysis of the looming child care cliff, The Century Foundation has projected the impact of the cutoff for children, families, and state economies, including for all fifty states and the District of Columbia.

We find that:

- More than 70,000 child care programs—one-third of those supported by American Rescue Plan stabilization funding—will likely close, and approximately 3.2 million children could lose their child care spots.

- The loss in tax and business revenue will likely cost states $10.6 billion in economic activity per year.

- In addition, we project that millions of parents will be impacted, with many leaving the workforce or reducing their hours, costing families $9 billion each year in lost earnings.

- The child care workforce, which has been one of the slowest sectors to recover from the pandemic, will likely lose another 232,000 jobs.

- In six states—Arkansas, Montana, Utah, Virginia, West Virginia, as well as Washington, D.C.—the number of licensed programs could be cut by half or more. In another fourteen states, the supply of licensed programs could be reduced by one-third.

Our findings underscore the urgent need for immediate funding and long-term comprehensive solutions at the federal level that offer safe, nurturing, and affordable child care options to every family.

Additionally, TCF today is releasing new nationwide public opinion polling, conducted by Morning Consult, that shows that a strong majority of Americans are concerned about the looming child care cliff and overwhelmingly prefer candidates for office who champion policies to expand quality, affordable child care. A summary of the polling is available here.

Introduction

Darlene Brannan runs Kids Korner Academy in Durham, North Carolina. Kids Korner Academy has been operating since 2009, serving children ages 6 weeks to 13 years. At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, they took out a loan to keep their program open, grateful for their dedicated teachers who came to work every day, and created a virtual option for their school-age children. Child care stabilization funds from the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) allowed them to reduce tuition, raise staff pay to about $20 an hour, offer professional development, and bring in new toys and furniture to make it a great place for kids during a stressful time.1

The children and families served by Kids Korner Academy have benefited from the well-paid and trained early educators, the reduction in child care tuition, and an engaging environment that ARPA funds made possible. And they are in good company with the millions of children and their families around the nation whose child care programs have received this kind of support.

Just like clean water, safe food, and good public schools, high quality, affordable, and accessible child care is a national priority that benefits everyone. Families across all income levels share the same determination to provide the best possible foundation for their children, especially in their early years. Two-thirds of children under age 6 have all of their parents (either solo or coupled) in the workforce.2 Parents need the freedom to afford child care and to have peace of mind that their children are safe and nurtured while parents go to work or to school and make the choices that are best for their families.

Families throughout the United States need a variety of affordable child care options that employ qualified and caring early educators who are able to meet children’s diverse needs and help them thrive. But this is not the reality for most families, who are obstructed at every turn by a scarcity of child care options that meet their budget or needs. The average annual cost of child care currently is more than $10,000 per year for one child, and in some states, it’s as much as $15,000 to $20,000 per year.3 That’s more than the price of a mortgage, rent, or public college tuition in most states.4 Nor is it the reality for many child care providers, who are finding it increasingly difficult to hire or retain passionate staff members who can support themselves on child care’s paltry wages—an average of $13.50 an hour for their complex and valuable work.5

The problem of high tuition prices, low early educator wages, and decreasing program supply has grown in severity6 for several decades, but was pushed to crisis levels by the COVID-19 pandemic, which laid bare the vulnerabilities and limitations of the United States’ child care system. All told, the United States lost an estimated 20,000 child care programs7 in the first two years of the pandemic, nearly 10 percent of its pre-pandemic amount of child care programs. Though these numbers represent a devastating setback for thousands of impacted children, families, and early educators, the toll could have been far worse.

The COVID-19 pandemic also made clear how great of an impact federal investment in child care and early learning can have: when a devastating disease caused an historic economic downturn, the federal government responded by making unprecedented investments in the American people and economy. The American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA),8 passed in 2021, gave states close to $40 billion in federal emergency relief funds for child care, which proved a much-needed lifeline for many child care providers.

While the pandemic sent the child care sector deeper into crisis, ARPA stabilization funds prevented it from collapsing altogether. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services found that the $24 billion in relief funds distributed to states served 220,000 child care providers, saved the jobs of more than 1 million early educators, and enabled continued care for as many as 9.6 million children.9 Child Care Aware of America recently found that, with the stabilization funding out in the field, the number of licensed child care centers returned to pre-pandemic levels in 2022, and the trend of declining family child care homes slowed.10

The ARPA stabilization funds that staved off the child care sector’s collapse will come to an abrupt end in September 2023. When these resources swiftly and suddenly disappear, this funding cliff will once again place the sector in danger, as it will be forced to contract, shedding caregivers and care slots in a cascade that will not only upend millions of families’ child care arrangements but also hurt regional economies. In this report, we analyze what children, families, and state economies stand to lose once the United States hits the “child care cliff.”

Without ARPA Funds, COVID-Era Child Care Progress Will Evaporate

Before the pandemic unfolded, families across the country were already facing child care costs that were out of reach, child care deserts, and inhospitable workplace policies due to the nation’s failure to invest in a comprehensive child care and early learning system.11 Slightly more than half of the country lived in a child care desert—defined as an area where there are more than three children under age 5 for each licensed child care slot.12 The supply of licensed family child care homes and other home-based child care (HBCC) providers was on the decline. One study13 found that the number of HBCC providers on state administrative lists has declined by 25 percent across the country over the past decade, despite the significant demand.14 Similarly, the number of small child care centers—those serving fewer than 25 children—declined by nearly 30 percent prior to the pandemic.15

Once the pandemic began, school, camp, and child care closures—and the increased costs of continued operations for those programs that were able to remain open—further exposed the vulnerabilities of the child care and early education sector.16 As the number and variety of child care options shrank, parents and other caregivers were forced to leave their jobs, cut their work hours or scramble for other child care solutions during a time when the pandemic made isolating one’s own family the safest option.

The ARPA stabilization funds—the largest investment in child care in American history—helped stem the tide of this sectoral collapse by shoring up 220,000 providers and helping them to pay for rent and mortgage, utilities, and higher wages, and to invest in increased health and safety measures during the pandemic. When the federal funds expire in September, this progress toward a better-resourced child care sector that can provide the quantity and quality of care that America needs will be reversed, and the long-felt stresses of insufficient supply and unaffordable prices of child care will not only return, but will grow exponentially.

In November 2021, the House of Representatives passed legislation that would have significantly expanded the supply of child care and early learning options, reaching an estimated 16 million children.17 The stabilization funds were enacted while Congress was moving this legislation forward, imagining that the resources to provide affordable, high-quality child care to the vast majority of families would be in place by the time the stabilization funding ended. Instead, this legislation did not pass the Senate, and as a result, the nation now faces a devastating child care cliff.

More than 70,000 Child Care Programs Projected to Close

The country’s already-strained child care sector faced an unprecedented crisis during the pandemic. New federal investments in child care over the past two years have been a lifeline for the child care sector and the families who rely on it. States have been using these funds to shore up safe, nurturing options for families by keeping providers’ doors open, raising compensation and benefits for early educators, lowering costs for families, and supporting the operating costs required to temporarily stabilize the supply of child care.

Using data from a survey of 12,000 early childhood educators from all states and settings18—including faith-based programs, family child care homes, Head Starts, and child care centers—and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Child Care,19 we found that approximately one-third of child care providers who received stabilization funding are likely to close as a result of the loss of funding.

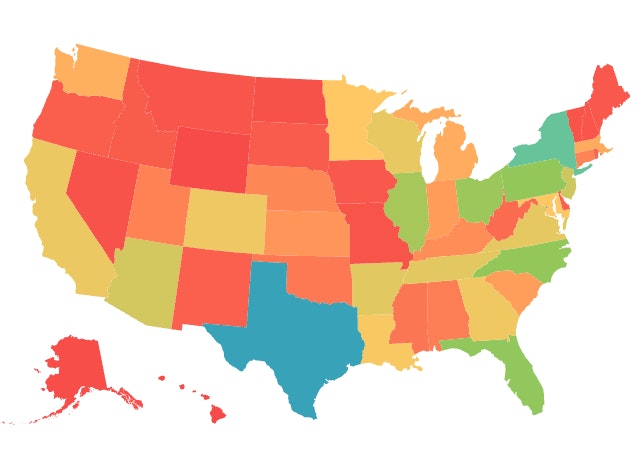

Our analysis finds that more than 70,000 child care programs are projected to close, shutting down child care slots for 3.2 million children and their families. (See Map 1.)

Map 1

Download State-specific fact sheets.

While the child care cliff will affect families in every state, some will be hit particularly hard. Our projections show that in Arkansas, Montana, Utah, Virginia, Washington, D.C., and West Virginia, the number of licensed programs could be cut by half or more. In another fourteen states, the supply of licensed programs could be reduced by a third.

As these programs close, many early educators are projected to lose their jobs. Early educators, who are primarily women and disproportionately women of color, are significantly underpaid—at $13.50 an hour—for the valuable and complex work they do. The long history of Black women as caregivers is rooted in inequity and created the foundational racial, gender, and economic inequities that are reflected today through the devaluation of the child care and early education profession.20 And so, even though early educators receive little pay for the work they do, and demand for their services is soaring, the disappearance of stabilization funds will mean that child care providers will need to make cuts, which means shrinking staff.

The child care staffing shortage that preceded and continued through the pandemic will return with a vengeance, putting upward pressure on prices as child care businesses choose between raising wages to attract early educators—or going out of business.

When the ARPA stabilization funds cease, child care will be starved of resources. The child care staffing shortage that preceded and continued through the pandemic will return with a vengeance, putting upward pressure on prices as child care businesses choose between raising wages to attract early educators—or going out of business.21 And, in a historically strong job market, many early educators are leaving the sector for higher-paying jobs elsewhere. While most sectors have recovered from the pandemic-induced recession, the employment level for child care workers is 4.8 percent below what it was in February 2020.22 As private sector companies raised wages and improved benefits to recruit and retain workers in recent years, child care providers were largely stymied by being under-resourced, leaving the child care sector one of the lowest paid professions in the country.23 The lack of resources after ARPA stabilization funds cease will only further exacerbate both child care’s unaffordable prices and scarcity of options.

More than Three Million Children to Lose Child Care

As noted above, the loss of 70,000 child care programs could impact approximately 3.2 million children. Even if all of those programs don’t close, the losses to children will occur as a result of higher tuition that parents won’t be able to afford and fewer openings as a result of staffing shortages. In many larger states, the loss of funding could mean lost access for significant numbers of children and families, including more than 200,000 children in Florida, nearly 130,000 in Illinois, 250,000 in New York, and more than 300,000 in Texas. (See Map 2.)

MAP 2

Download State-specific fact sheets.

Today, most parents work, and so they need affordable, high-quality child care and early learning options for their children. Moreover, they need child care and preschool options that help their children build on the learning and development experiences they get at home with their families. Parents need safe, nurturing care options for their children. As families lose access to child care, many parents will need to leave employment or reduce their hours to fill the gap, losing earnings and jobs.

Parents Projected to Lose Nearly $9 Billion in Earnings Each Year

When parents have to reduce work hours or leave their jobs entirely due to a lack of affordable child care, there are widespread impacts for children’s well-being, family economic security, racial and gender equity, and local and state economies. This is why care investments, much like infrastructure investments, help build broader economic growth overall; child care helps parents participate in the economy. One study found that women’s labor force participation contributes $7.6 trillion to the GDP every year,24 but the lack of child care is a significant hindrance to that contribution.25 Our analysis found that, on aggregate, parents are projected to lose nearly $9 billion per year in earnings as a result of the expiration of the federal child care funding. This reflects a combination of parents leaving their jobs or cutting their work hours to address gaps left by disruptions in child care arrangements.

Two-thirds of Americans live paycheck to paycheck.26 This includes a growing number of higher-income households.27 Beyond this, 10 percent of families face food insecurity.28 Any disruption in employment for parents is going to make it more likely that families will face economic hardship or food insecurity. The RAPID survey found that in March 2023, one in three families faced at least one form of material hardship, including trouble affording food, rent, child care, or utilities.29 For all of these trends, Black and Latinx households are much more likely than white households to face material hardship.30

Our findings show that as a result of the upcoming child care cliff, millions of parents will be impacted, and many will either leave the workforce or reduce their hours. In addition to the immediate earnings losses, significant evidence shows that these parents will also face long-term consequences. Research has repeatedly shown that even short disruptions in work can lead to long-term lifelong earnings losses.31 A study by the Center for American Progress, found that a woman who takes five years off at age 26 for caregiving, “would lose $467,000 over her working career, reducing her lifetime earnings by 19 percent.”32 Even reducing hours to work part-time can have negative effects on lifelong earnings for women. Concerningly, an analysis from the Bureau of Labor Statistics found that mothers become more likely than women without children to have part-time jobs during their prime-working age years, ages 25–54, especially mothers of young children.33 Whether leaving work full time or choosing to take on a part-time role, these workforce disruptions have long-term consequences. Part-time jobs are also less likely to offer employer-sponsored retirement savings accounts, and short work disruptions can still reduce Social Security benefits at the time of retirement.34

These disruptions also impact child well-being. Children benefit from their parents’ economic stability. Family income impacts children’s cognitive development, physical health, and social and behavioral development because it is connected not only to parents’ ability to invest in goods and services that further child development, but also to the stress and anxiety parents can suffer when faced with financial difficulty, which in turn can have an adverse effect on their children.35

State Economies Could Lose $10.6 Billion in Tax Revenue and Productivity Each Year

One study found that the United States already loses $122 billion a year in lost earnings, productivity, and tax revenue due to the lack of a functioning child care system.36 The additional blow to the economy from the expiration of ARPA stabilization funds will have widespread effects, including the $9 billion in lost earnings noted above, the more than $300 million predicted to be lost in state income tax revenue, and more than $10.3 billion in likely losses to employers from increased employee turnover and reduced productivity from child care disruptions.37 States rely on tax revenues as a significant share of funding for their activities. According to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 72 percent of state revenues come from income, sales, and other taxes.38 As a result, state revenues are inextricable from economic activity. Lower income through workforce disruptions will reduce state income tax revenues. This means that states, which must balance expenditures with revenues, will have to make cuts if their revenues drop as a result of lower economic activity. The two biggest buckets of state spending are often spending on education and health care.39 Lower parental employment will mean less funding for the essential services that state and local governments provide.

Workforce disruptions are also a hardship for businesses. Lost productivity and turnover create additional costs for hiring and training new hires. One national survey found that the majority of small business owners feel that the lack of child care for their workers harms their business.40 ReadyNation estimated that the lack of affordable child care costs businesses $23 billion each year.41 Solving child care is not only essential for family economic security, but for the businesses and communities that are supported by the labor force participation of parents.

Additional losses to state economies will accrue due to the loss of sales tax and the child care workforce shrinking by a projected 200,000 jobs. While these are not well-paid jobs, despite the fact that they should be, the decline will have an impact on the economy in the loss of those wages and tax revenues as well.

States Are Scrambling as Federal Funds Expire

Given that the deadline to spend ARPA stabilization funds is now looming, states are contending with strategies for maintaining their struggling child care sectors. Federal intervention through subsidizing the child care market is the only sure way to lower the price of child care for families while raising wages for early childhood educators. With no sign of imminent federal action, many states have taken proactive measures to support their child care sectors in anticipation of the loss of federal ARPA dollars and in doing so, have identified a diverse set of pathways other states can follow as they seek to implement long-term investments in child care infrastructure.

States have had great success in using ARPA and other emergency relief funds to stabilize their child care sectors following mass job losses and program closures during the first two years of the pandemic. The end of these funds will have broad-reaching implications for child care programs and families in every state.

In Wisconsin,42 funding for the Child Care Counts Stabilization Payment Program will be cut in half.43 The support these funds provided saved more than 3,300 child care programs, 22,000 early educator jobs, and enabled continued care for 113,000 children by providing emergency assistance during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic.44 Once ARPA funds run out, our analyses show Wisconsin risks losing 2,110 child care programs, impacting more than 87,000 children. Our calculations show turnover from parents leaving the workforce would cost the state of Wisconsin more than $232 million in parental wages, a substantial but entirely preventable loss. Even while APRA funds remain, however, the dearth of accessible and affordable care has led Wisconsin families to report that they are planning pregnancies around the availability of child care slots or deferring having children altogether.45

In Texas, too, emergency relief funds from the CARES Act and ARPA enabled the Texas Workforce Commission to distribute $3.45 billion in direct funding to child care programs over two years.46 This funding was used to subsidize overhead costs for child care programs, wages and job training for early educators, and support program expansions into child care deserts.47 Sixty percent of respondents in a survey by the Texas Association for the Education of Young Children said their program would have closed without this aid.48 Texas stands to lose nearly 4,000 child care programs once stabilization funds sunset, leaving over 300,000 children without child care. For a state as populous as Texas, the total cost of turnover and lost productivity is nearly $1 billion. And as the child care supply dries up due to program closures and job losses, tuition prices will be driven up, creating an added burden for parents already struggling to afford care.

Protestations from parents that child care is too expensive and too hard to find are echoed throughout the country. Virginia’s United Way of Greater Charlottesville warns that child care prices in the state are higher than ever before, ranging from $14,500 per year for a toddler to $24,000 per year for an infant.49 Early in the pandemic, Virginia invested $203 million in ARPA funding for child care and was able to expand eligibility for families with young children seeking subsidies to 85 percent of the state median income.50 Virginia also updated their process for reimbursing child care providers and used federal funds to reimburse providers for the true cost of care as opposed to the market rate, which severely underestimates the bills that providers pay to operate their programs.51 Without the support of federal funds, Virginian families will see a decline in child care options and struggle to pay for the unaffordable child care that is still available.

Parents pay the greatest share of their earnings on child care in New York, where Bronx families, for example, spend a staggering 47 percent of the median household income on care for a single child.52 Unaffordable child care prices put parents in an impossible double bind: child care is too expensive, but few families can afford for a parent to lose needed income by leaving their job. We project that over 10,000 New York parents across the state would be forced out of the workforce, and an additional 74,000 forced to cut their hours, standing to lose a collective $846 million in household income. This is economically unsustainable for both families and state economies.

Even when families can afford care, identifying quality care close to home can be challenging: the child care supply is dwindling as programs close classrooms and extend waitlists to compensate for poor staff retention rates.53 The primary reason early childhood educators leave their jobs is unsustainably low wages, and while service jobs in retail and the food-industry raised wages during the pandemic, child care wages have stagnated.54

All of these issues—high tuition prices, low early educator wages, and decreasing program supply—can be attributed to a critical lack of public investment in child care. The distribution of emergency relief funds during the pandemic alleviated these issues and demonstrated that government support of child care through tuition waivers, stipends, reimbursements, expanded eligibility, and direct payments to parents and providers alike can keep child care programs open and parents in the workforce. A child care sector without public funding that is once again simply left to “the market” to support will see the return of longterm problems. States have learned these lessons from the pandemic and are seeking avenues to ensure their child care sectors can weather the end of ARPA stabilization funds.

With federal funds expiring, governors and state legislatures are attempting new measures to fund child care. For example, in Maine, Governor Janet Mills has proposed a budget that would allocate $24 million in federal funds for child care and early education to continue the investments that were initially made in early educator wages and professional development opportunities using ARPA funds.55 Meanwhile, Democrats in Maine’s Senate have proposed a bill that would continue pandemic-era stipends for child care workers and double their amount from $200 to $400.56 These investments in staff wages are a deliberate effort to stem the tide of job losses in the child care sector.

In Minnesota, the 2023 legislative session included historic investments in child care and early education. During the first year of the pandemic, 96 percent of providers in Minnesota who received child care stabilization grants said the grants helped them stay open and operate.57 The state required that providers spend 70 percent of their grants on compensation. Providers used the funds primarily to raise wages and provide bonuses, with 84 percent saying it helped them retain staff and 61 percent saying it helped them recruit new staff.58 As these funds expire, the legislature, following the leadership of Governor Walz, has voted to invest $750 million in new spending on child care and early learning, including adding 1,000 new child care slots, raising reimbursement rates for early educators, and lowering costs for families.59

Oregon’s Governor and the state legislature are proposing significant new investments in child care and early learning. Unfortunately, without federal partnership, the funds come up short. Their proposal would still leave the state’s total available funding below the level they received from ARPA.60 This makes it abundantly clear that while states can and should dedicate funds toward alleviating the strain on their child care sectors, the federal government needs to continue to commit funding in order for states to continue strengthening their child care workforce and building an adequate supply of high-quality and affordable child care.

Other states’ efforts to find long-term funding sources preceded the pandemic. While they were not implemented as a direct response to the sunsetting of ARPA funds, they offer potential models for raising money that other states can replicate. New Mexico made history when it passed a constitutional amendment61 dedicating funding from the Land Grant Permanent Fund to early childhood education.62 In addition, in recent years, Missouri and Maryland have followed Louisiana’s lead in finding additional sources of funding, by funding early childhood education through a portion of funds raised from sports betting.63 Another model is the tri-share program—a public private partnership that splits the price of child care evenly among parents, employers, and the state. Michigan launched the country’s first tri-share pilot program in 2021, giving the state administrative oversight, which minimized a substantial burden for both employers and child care providers, and enabling employers to invest in a service that has improved staff retention by 80 percent.64 Meanwhile, North Carolina’s recent House budget proposal followed Michigan’s example and outlined a tri-share program.

States also received $15 billion in child care supplemental funds that were included in their child care development block grants. Those funds have been used to expand child care assistance to families who had not previously received it (by changing eligibility rules or simply having the resources to reach more families through a program that is historically underfunded) and making child care more affordable by reducing or eliminating family copayments or fees, and will continue to be available until September 30, 2024.65 In addition, some states have also used ARPA state and local relief funds to further supplement their child care spending.66 For example, policymakers in Rhode Island, New Jersey, and Evanston, Illinois are among those who have used these funds to support higher wages for early educators. In Connecticut, Nevada, and Fort Bend, Texas, these funds have also been used to lower child care costs for families.67 These temporary federal sources are helpful, but not enough.

Efforts to shore up the child care sector at the state level demonstrate nationwide awareness and a justified sense of urgency to prevent further decline in a critical sector. Without further investment at the federal level to prevent an abrupt drop-off in resources, these efforts will fall short. Providers, parents, and children will pay the price.

Mitigating Catastrophe

States can make a significant difference in improving child care’s accessibility, affordability, and quality, but to truly build the comprehensive child care and early learning system America needs requires a national effort. The federal government must contribute in partnership with states, localities, employers, communities, and families to ensure that the next generation children and their families have the resources they need to thrive.

Congress got close to achieving comprehensive child care in 1971, and again in 2021. As the largest investment in child care in American history expires in September, children and families cannot wait another fifty years. Congress must act now with immediate funding and sustainable solutions. The Child Care for Working Families Act, for example, would make child care and early education affordable so that any parent—no matter where they live or what they look like—would have great care options for their children.68 The stakes are high: 70,000 child care programs serving more than 3 million children; 200,000 early education jobs, 3 million parents and $10.6 billion in state economic revenue from lost productivity and taxes. When America decides something is a priority, we find the funding. It’s time to prioritize child care to ensure all our families are able to thrive.

The authors would like to thank Khaliun Battogtokh, Stephanie Schmit, Alycia Hardy, Meghan Salas Atwell, and Helen Hare for their feedback and assistance.

Appendix: Methodology

Number of Programs, Children, and Parents Impacted

To calculate the number of child care programs, children and parents who will be impacted by the expiration of stabilization funding, we used a combination of data sources and assumptions. The Administration for Children and Families Office of Child Care fact sheets provide state-level data on the number of child care centers and family care providers receiving Child Care Stabilization grant funding and the number of children reached through this funding.69 These data points were multiplied by the National Association for the Education of Young Children’s (NAEYC’s) state-level survey data from a survey of 12,000 early childhood educators from all states and settings on the share of providers receiving grant funds that reported their program would have closed without the grants to estimate the number of providers in each state that would potentially close and the associated number of children that would be impacted.70 It should be noted that the unit of analysis in the NAEYC survey data used is the individual, while the unit of analysis in the ACF factsheets is the program. It is possible that multiple individuals from the same program completed the NAEYC survey and responded that their program would have closed without the funding. As a result, we may be slightly over-estimating the number of programs that may close as a result of a loss in funding. However, in other parts of this analysis we use conservative estimates wherever possible to minimize the risk of overestimating the impact of the cliff overall. Additionally, future shocks to the economy could cause additional closures beyond the impact of losing stabilization funding.

Because not all children are growing up in two-parent households and because some households have more than one child under age 13, estimating the number of parents impacted was slightly less straightforward. Using the 2021 American Community Survey (ACS) data, we examined the state-level distribution of children under age 13 across different household types (married-couple, single mother, single father) and applied this distribution to the estimated number of children under age 13 impacted by a loss of Child Care Stabilization grants. Then, we estimated the average number of children under age 13 per household by household type at the state level. Dividing the number of children under age 13 impacted in each state in each household type by the average number of children under age 13 in each type of household then allows us to estimate the number of households of each type impacted by the loss of grant funding. From there we calculated the number of parents impacted by multiplying the number of married-couple households by 2 and adding to that product the number of single mother and single father households impacted.

Number of Parents Leaving the Labor Force

To estimate the likely number of parents who will leave the labor force as a result of the loss of child care, we started by estimating the number of parents potentially impacted by the loss of funding for the Child Care Stabilization grants that are employed. We used data from the National Center for Education Statistics 2019 Early Childhood Program Participation Survey to estimate the share of parents who stated that their primary reason for seeking child care was to provide care while a parent was at work or school and were employed when they did/did not find care for their children. These estimates were calculated separately by parent gender and marital status.71 We applied the percentages of parents who found child care that were employed to the number of parents impacted (by household type—single mothers, married mothers, all fathers) to estimate the share of parents impacted that are currently working. We then applied the percentages of parents who did not find child care that were employed to the number of parents impacted (by household type) and then subtracted this from our estimates of the number of impacted parents currently working to estimate the number of parents that would leave the labor force if funding was cut.

Wages Lost Due to Parents Leaving the Labor Force

Because the characteristics of the parents who would leave the labor force if child care were no longer available are likely different than those who would remain in the labor force even if they experienced a disruption in child care availability, we cannot simply use the average wages of parents of children under age 13 as an estimate of the average wages lost among parents leaving the labor force.

Instead, we employ a similar methodology as that used in previous reports by TCF.72 We utilized a Heckman two-step model to first estimate the likelihood of parents being employed and then, correcting for sample selection bias, we estimate parents’ wages based on a number of characteristics (i.e. age, educational attainment, race/ethnicity, occupation, state, etc.). We then assumed that the characteristics of parents of children under age 13 not currently in the labor force in the 2021 ACS data would be a reasonable proxy for the characteristics of parents of children under age 13 that would leave the workforce if they lost access to child care because of the expiration of the Child Care Stabilization grants. These parents were run through the wage equation estimated and we calculated the average predicted wages for these parents (by gender and household type). These average values were then multiplied by the number of impacted parents to estimate the total wages lost due to parents leaving the labor force in each state.

Number of Parents Reducing Working Hours

To estimate the number of parents reducing work hours, we first needed to estimate the share of impacted parents that are working full-time/part-time. To do this, we first calculated the share of parents of children under age 13 by state and household type that were working full-time/part-time in the 2021 ACS data. Because the impacted parents had access to affordable, reliable child care through the stabilization grants, we assumed that full-time employment rates would be higher among these parents than in the labor force overall. Using data from CAP, which says that 32 percent of parents working part-time and 34 percent of parents working full-time would request more hours at work if they had access to affordable, reliable child care, we re-calculated the share of parents of children under age 13 by state and household type assuming that 32 percent of part-time workers would switch to full-time.73 The number of parents switching to full-time employment was then taken as a share of the new, higher number of parents working full-time to estimate the share of currently full-time employed parents that would reduce their hours to part-time if they experienced a disruption in their access to affordable, reliable child care. Simultaneously we estimated the number of current full-time employed parents in each state that would increase their hours and took this as a fraction of the new, higher number of parents working full-time. This is the percentage of parents that are currently full-time employed that would reduce their hours slightly (but still work full-time) if they experienced a disruption in their access to affordable, reliable child care.

Lost Wages Due to Parents Working Fewer Hours

Next, we estimated average annual hours worked by full/part-time status, gender, and household type as well as average hourly wage. We then took the difference between current annual average full-time hours worked and part-time hours worked and multiplied it by the appropriate hourly wage and the number of impacted parents that would reduce their hours to part-time to estimate the lost wages due to some parents switching to part-time employment as a result of their loss of child care access. To estimate the losses due to full-time employed parents reducing their hours but still working part time, we relied on data from Belfield, which finds that on average parents lose two hours per week of work time due to child care problems (104 hours per year).74 We then multiplied the annual reduction in hours worked by the average hourly wage, and then multiplied the result by the estimated number of impacted parents that would reduce their full-time hours.

Federal and State Tax Revenue Lost Due to Reductions in Parental Employment

To estimate the total losses in federal and state tax revenue as a result of parents leaving the workforce, we used the 2021 ACS data to calculate the median household income of parents in different households in which at least one parent is not in the labor force (e.g. married couple household, mother not in the labor force). We also calculated the average number of dependents in each household type by state (for use as inputs in the tax simulation model as to determine eligibility for tax credits). We then used the NBER’s Taxsim35,75 a microsimulation model of federal and state income tax systems, to estimate the federal and state tax liability of each household when at least one parent is not in the labor force.

Next, using the estimates above of the annual wages lost due to parents leaving the labor force, we added these annual earnings onto the household income of households with the relevant parent currently not in the labor force to estimate the new, higher household income. New federal and state tax liabilities were calculated with this higher level of household income. The difference between the two tax liabilities, multiplied by the number of households impacted, represents the amount of tax revenue lost at the federal and state level due to parents leaving the labor force.

A similar methodology was used with the population of parents reducing hours worked.

Turnover Costs to Employers

In addition to some parents leaving the workforce (discussed above), a number of working parents may also leave their current jobs to find another job as a result of the disruption to their child care arrangement if their current provider were to close its doors. This could be because their current employer is not understanding of their child care situation, or because they are seeking a job with more flexible hours or teleworking options, or a number of other reasons. Data on the share of parents expected to leave their jobs (either for new ones or to leave the labor force entirely) are somewhat limited and often do not separate the two. The Household Pulse Survey provides data on the share of households in which an adult in the household left a job to care for their children as a result of recent child care disruptions, but does not specify whether the adult intended to find another job or whether they left the labor force. Estimates vary from week to week, but in the period between April 14 through May 24, 2021 between 13 percent and 15 percent of households experiencing a child care disruption reported that an adult left a job.76 Another report estimated that 26 percent of parents have quit a job as a result of child care problems.77

Because both data sources do not clearly identify whether these parents leaving their jobs are looking for new jobs or are leaving the workforce entirely, we assume that they are inclusive of both types. To be conservative with our estimates of the effects on turnover, we chose 15 percent as the share of parents expected to leave their job as a result of child care disruptions because it is on the lower end of the range of estimates provided in available data sources. This share was then applied to our estimates of the number of impacted working parents to calculate the number of parents expected to leave their jobs.

Following Boushey and Glynn (2012), we assume that the cost of employee turnover is 21 percent of workers’ annual wages.78 We applied this percentage of the estimated annual wages of mothers and fathers expected to leave their jobs and added these estimates up across each state. Because of the two assumptions made above, we expect that these estimates of the cost of turnover will be underestimates.

Lost Productivity

In addition to the hours worked analysis described above, we also assumed that parents would need to miss a certain number of days of work per year due to unforeseen issues with childcare. As with the turnover analysis, data on the share of parents that would miss work as a result of child care disruptions are limited and often separate those that take paid leave and those that take unpaid leave. Data from the Household Pulse Survey, for example, show that between April 14 and May 24, 2021, between 22 percent and 25 percent of households experiencing a child care disruption had an adult in the household take paid leave in order to care for their children and between 19 percent and 26 percent took unpaid leave.79 It is likely that there is some overlap in these two percentages (e.g., that some parents will take paid leave, run out of days, and then take unpaid leave), though it is not clear the extent of the overlap. Because of this, however, we cannot simply add the two percentages together to estimate the share of parents that would take any kind of time off. For the purposes of this analysis, we assumed that 22 percent would take leave, as it was in the middle of the range of estimates available through the Household Pulse Survey.

This percentage is applied to the number of parents impacted by program closures that are expected to remain in the workforce in order to estimate the number of parents that may miss work to take care of their children when a disruption in child care is experienced. Because this percentage is based on the share of parents taking paid or unpaid leave, not the share of parents taking any leave, we expect that this will be an underestimation of the number of parents taking any leave.

Following previous TCF analyses, we assume that parents that do miss work will miss an average of nine days per year.80 Utilizing data on the average usual hours per day and per year of parents of children under age 13 from the ACS (by household type), we estimated the share of total annual hours lost due to parents missing work due to child care disruptions. This was then multiplied by an estimate of revenue per worker (state GDP divided by the total number of workers in the state),81 and the number of parents expected to miss work each year due to child care disruptions to estimate total annual productivity lost.82

Potential Number of Child Care Providers Leaving Their Jobs

State-level survey data from NAEYC was used to estimate the number of child care providers currently considering leaving their jobs. Their survey specifically asks “Are you considering leaving your program or closing your family child care home?”83 Providers are reported as considering leaving if they responded “yes” or “maybe” to this question. In some states, percentages of providers were not reported, but rather the number of providers responding “yes” or “maybe” was reported. In this case, we estimated the percentage of providers by dividing the number responding in the affirmative by the total number of respondents in the state. As noted above, the NAEYC data is collected at the individual level and may include multiple respondents from the same program. However, this is less likely to be problematic in this portion of the analysis because we are also examining an individual level outcome.

We then pulled data on total employment levels and average annual wages of child care workers84 in each state from BLS and multiplied total employment by the share of providers in each state that are considering leaving their jobs to estimate the total number of child care providers in each state that would potentially leave their jobs if the current child care crisis is not addressed.85

Notes

- Darlene Brannon, via YouTube, Child Care Aware of America, accessed May 3, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MQtu_ygiZWA&list=PLdPTHOpLEUz7gWn-gWpIUQGvgqE0uEK26&index=1.

- Kids Count Data Center, “Children Under Age 6 With All Available Parents In The Labor Force In United States,” Annie E. Casey, 2021 Data, https://datacenter.aecf.org/data/tables/5057-children-under-age-6-with-all-available-parents-in-the-labor-force?loc=1&loct=1#detailed/1/any/false/2048,1729,37,871,870,573,869,36,868,867/any/11472,11473.

- Catalyzing Growth: Using Data to Change Child Care,” Child Care Aware of America, 2022, accessed May 4, 2023, https://www.childcareaware.org/catalyzing-growth-using-data-to-change-child-care-2022/

- Ibid.

- Elise Gould, Marokey Sawo, and Asha Banerjee, “Care workers are deeply undervalued and underpaid: Estimating fair and equitable wages in the care sectors,” Economic Policy Institute, July 16, 2021, https://www.epi.org/blog/care-workers-are-deeply-undervalued-and-underpaid-estimating-fair-and-equitable-wages-in-the-care-sectors/.

- Juliana Kaplan, “Healthcare, College Education, and Childcare Started Getting Worse Decades Ago. Now We’re All Finally Feeling It.,” Business Insider, April 8, 2023, https://www.businessinsider.com/how-education-healthcare-childcare-got-so-expensive-feeling-it-now-2023-4.

- Julie Kashen and Rasheed Malik, “More Than Three Million Child Care Spots Saved by American Rescue Plan Funding” The Century Foundation, March 9, 2022, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/three-million-child-care-spots-saved-american-rescue-plan-funding/.

- H.R.1319—117th Congress (2021-2022): American Rescue Plan Act of 2021,” March 11, 2021, https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/1319/text.

- “ARP Child Care Stabilization Funding State and Territory Fact Sheets,” Government, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, accessed May 3, 2023, https://www.acf.hhs.gov/occ/map/arp-act-stabilization-funding-state-territory-fact-sheets.

- “Catalyzing Growth: Using Data to Change Child Care,” Child Care Aware of America, 2022, https://www.childcareaware.org/catalyzing-growth-using-data-to-change-child-care-2022/#LandscapeAnalysis.

- Julie Kashen, Sarah Jane Glynn, and Amanda Novello, “How COVID-19 Sent Women’s Workforce Progress Backward: Congress’ $64.5 Billion Mistake,” The Century Foundation, October 29, 2020, https://tcf.org/content/report/how-covid-19-sent-womens-workforce-progress-backward-congress-64-5-billion-mistake/.

- Rasheed Malik, Katie Hamm, and Leila Schochet, “America’s Child Care Deserts in 2018,” Center for American Progress, December 6, 2018, https://www.americanprogress.org/article/americas-child-care-deserts-2018/.

- Yuko Yadatsu Ekyalongo, Weilin Li, and Audrey Franchett, “As the number of home-based child care providers declines sharply, parents are leaving more negative online child care reviews,” Child Trends, March 27, 2023, https://doi.org/10.56417/962z2356o.

- “Home-based Early Care and Education Providers in 2012 and 2019: Counts and Characteristics,” National Survey of Early Care and Education (NSECE), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, May 2021, https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/opre/NSECE-chartbook-homebased-may-2021.pdf.

- Analysis based on NSECE data.

- Simon Workman and Steven Jessen-Howard, “The True Cost of Providing Safe Child Care During the Coronavirus Pandemic,” Center for American Progress, September 3, 2020, .https://www.americanprogress.org/article/true-cost-providing-safe-child-care-coronavirus-pandemic/.

- Julie Kashen, “How Congress Got Close to Solving Child Care, Then Failed,” The Century Foundation, December 12, 2022, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/how-congress-got-close-to-solving-child-care-then-failed/.

- “Uncertainty Ahead Means Instability Now: Why Families, Children, Educators, Businesses, and States Need Congress to Fund Child Care,” National Association for the Education of Young Children, State by State Survey Briefs, released December 2022, https://www.naeyc.org/state-survey-briefs.

- “ARP Child Care Stabilization Funding State and Territory Fact Sheets,” Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Child Care, accessed May 2, 2023, https://www.acf.hhs.gov/occ/map/arp-act-stabilization-funding-state-territory-fact-sheets.

- Julie Vogtman, “Undervalued A Brief History of Women’s Care Work and Child Care Policy in the United States,” National Women’s Law Center, 2017, https://nwlc.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/final_nwlc_Undervalued2017.pdf.

- Elliot Haspel, “There’s a massive child-care worker shortage and the market can’t fix it,” Washington Post, May 6, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2021/05/26/child-care-center-worker-shortage/.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, All Employees, Child Care Services [CES6562440001], retrieved June 8, 2023 from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CES6562440001.

- Julie Vogtman, “Undervalued A Brief History of Women’s Care Work and Child Care Policy in the United States,” National Women’s Law Center, 2017, https://nwlc.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/final_nwlc_Undervalued2017.pdf.

- “Female Labor Force Participation is Key to our Economic Recovery,” ReadyNation, Council for a Strong America, https://strongnation.s3.amazonaws.com/documents/1344/0bef73a7-549e-4b4a-bb7b-9701c9f96d5e.pdf?1627393858&inline;%20filename=%22Female%20Labor%20Force%20Participation%20Is%20Key%20to%20Our%20Economic%20Recovery%20Factsheet.pdf%22.

- Julie Kashen and Jessica Milli, “The Build Back Better Plan Would Reduce the Motherhood Penalty,” The Century Foundation, October 8, 2021, https://tcf.org/content/report/build-back-better-plan-reduce-motherhood-penalty/.

- Megan Leonhardt, “More than half of Americans raking in $100,000 or more are living paycheck to paycheck,” Fortune, January 30, 2023, https://fortune.com/2023/01/30/more-high-earning-americans-stretching-paycheck-inflation/

- Ibid.

- “Food Security Status of U.S. Households in 2021,” U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, October 17, 2022, https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-u-s/key-statistics-graphics.

- “Material Hardship Over Time,” RAPID Survey Project, March 2023, https://rapidsurveyproject.com/latest-data-and-trends.

- “High Material Hardship Persists for Families with Young Children,” RAPID Survey Project, April 2023, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5e7cf2f62c45da32f3c6065e/t/6430194d926e6a5e602cebfc/1680873806026/material_hardship_factsheet_apr2023.pdf.

- Michael Madowitz, Alex Rowell, and Katie Hamm, “Calculating the Hidden Costs of Interrupting a Career for Child Care,” Center for American Progress, June 21, 2016, https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/early-childhood/reports/2016/06/21/139731/calculating-the-hidden-cost-of-interrupting-a-career-for-child-care/.

- Ibid.

- Liana Christin Landivar, Rose A. Woods, and Gretchen M. Livingston, “Does part-time work offer flexibility to employed mothers?” Monthly Labor Review, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, February 2022, https://doi.org/10.21916/mlr.2022.7.

- Laura Valle-Gutierrez, “New Data Demonstrates Mothers’ Retirement Insecurity,” The Century Foundation, April 26, 2023, https://tcf.org/content/report/new-data-demonstrates-mothers-retirement-insecurity/.

- Julie Kashen and Halley Potter, “The Case for Child Care and Early Learning for All: Healthy Child Development and School Readiness,” The Century Foundation, September 02, 2021, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/case-child-care-early-learning-healthy-child-development-school-readiness/.

- Sandra Bishop. “$122 Billion: The Growing, Annual Cost of the Infant-Toddler Child Care Crisis: Impact on families, businesses, and taxpayers has more than doubled since 2018,” Ready Nation, February 2023, https://strongnation.s3.amazonaws.com/documents/1598/05d917e2-9618-4648-a0ee-1b35d17e2a4d.pdf?1674854626&inline;%20filename=%22$122%20Billion:%20The%20Growing,%20Annual%20Cost%20of%20the%20Infant-Toddler%20Child%20Care%20Crisis.pdf%22.

- Our analysis found overlap between the parental earnings data and the tax revenue and productivity data, such that we categorize parental earnings separately from the tax revenue and productivity data, which is different from how the Ready Nation report cited calculates the projected losses.

- “State Budget Basics,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 24, 2022, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/state-budgets-basics.

- Ibid.

- Julie Kashen, Julie Cai, Hayley Brown, and Shawn Fremstad, “How States Would Benefit if Congress Truly Invested in Child Care and Pre-K,” The Century Foundation, March 21, 2022, https://tcf.org/content/report/how-states-would-benefit-if-congress-truly-invested-in-child-care-and-pre-k/.

- “$122 Billion: The Growing Annual Cost of the Infant-Toddler Child Care Crisis,” ReadyNation, Council for a Strong America, February 2, 2023, https://www.strongnation.org/articles/2038-122-billion-the-growing-annual-cost-of-the-infant-toddler-child-care-crisis.

- Madison Lammert, “Wisconsin Families May Soon See Child Care Costs Rise as Funding Help Declines,” The Post–Crescent, April 21, 2023, https://www.postcrescent.com/story/news/education/2023/04/21/child-care-counts-cuts-could-mean-rising-costs-for-wisconsin-families/70132702007/.

- “Child Care Counts: Stabilization Payment Program Round 2,” Government, Wisconsin Department of Children and Families, accessed May 3, 2023, https://dcf.wisconsin.gov/covid-19/childcare/payments.

- Ibid.

- Madison Lammert, Jeff Bollier, “The new Wisconsin family? 1.7 kids, no picket fence and child care costs more than college,” Appleton Post-Crescent, Green Bay Press-Gazette, March 29, 2023, https://www.postcrescent.com/story/money/2023/03/29/wisconsin-families-face-high-child-care-costs-leading-some-to-delay-conception/69925270007/.

- “Child Care Relief Funding 2022,” Texas Workforce Commission, accessed May 3, 2023, https://www.twc.texas.gov/programs/child-care-relief-funding.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Anahita Jafary, “Child Care Costs at an All-Time High in Virginia,” NBC29, March 31, 2023, https://www.nbc29.com/2023/03/31/child-care-costs-an-all-time-high-virginia/.

- Pat Thomas, “Virginia Invests More than $203M to Expand Access to Child Care, Increase Support for Providers,” WDBJ7, April 2, 2021, https://www.wdbj7.com/2021/04/02/virginia-invests-more-than-203m-to-expand-access-to-child-care-increase-support-for-providers/.

- Karri Peifer, “Child Care Help Coming to Virginia,” Axios, September 28, 2022, https://www.axios.com/local/richmond/2022/09/28/child-care-virginia-reimbursements.

- Robbie Sequeira, “Bronx Families Spend More than 47% of Income on Childcare, the Most of Any U.S. County—Bronx Times,” Bronx Times, April 21, 2023, https://www.bxtimes.com/bronx-families-income-child-care/.

- Audrey Breen, “Child Care Centers Are Turning Away Families Due to Teacher Turnover,” UVA Today, February 15, 2023, https://news.virginia.edu/content/child-care-centers-are-turning-away-families-due-teacher-turnover.

- Ibid.

- “Governor Mills Announces $24 Million Federal Award to Strengthen Early Childhood Support for Maine Families,” State of Maine, Office of Governor Janet T. Mills, accessed May 4, 2023, http://www.maine.gov/governor/mills/news/governor-mills-announces-24-million-federal-award-strengthen-early-childhood-support-maine.

- Phil Hirschkorn, “Maine Legislators Propose Ways to Expand Access to Affordable Childcare,” WMTW, April 12, 2023, https://www.wmtw.com/article/maine-legislators-propose-ways-to-expand-access-to-affordable-childcare/43569932.

- “Child Care Stabilization Grant Summary—Year One,” Minnesota Department of Human Services, October 17, 2022, https://edocs.dhs.state.mn.us/lfserver/Public/DHS-8330A-ENG.

- Ibid.

- “Final Legislative Update,”Child Care Aware of Minnesota, May 25, 2023, https://www.childcareawaremn.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Final-2023-Legislative-Update-FINAL.pdf

- Ibid.

- “New Mexico Constitutional Amendment 1, Land Grant Permanent Fund Distribution for Early Childhood Education Amendment (2022),” Ballotpedia, accessed May 4, 2023, https://ballotpedia.org/New_Mexico_Constitutional_Amendment_1,_Land_Grant_Permanent_Fund_Distribution_for_Early_Childhood_Education_Amendment_(2022).

- Bryce Covert, “New Mexico Just Became the First State to Make Child Care Free for Nearly All Families,” Early Learning Nation (blog), May 26, 2022, https://earlylearningnation.com/2022/05/new-mexico-just-became-the-first-state-to-make-child-care-free-for-nearly-all-families/.

- “Gambling or Related Fees,” Child Care Technical Assistance Netowrk, accessed May 3, 2023, https://childcareta.acf.hhs.gov/systemsbuilding/systems-guides/financing-strategically/revenue-generation-strategies/gambling-or.

- The program currently serves 277 families and 239 child care providers, but Michigan is looking to expand coverage to all 300,000 eligible children in the state. Michelle Peng, “A New Model for Addressing the Child-Care Crisis,” Charter Works, April 30, 2023, https://www.charterworks.com/cheryl-bergman-tri-share/.

- Karen Schulman, “Child Care Rescue: How States Are Using Their American Rescue Plan Act Child Care Funds,” National Women’s Law Center, October 2022, https://nwlc.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Child-Care-Rescue-State-Uses-of-ARPA-Funds-NWLC-Report.pdf.

- Erica Meade and Sarah Gilliland, “Bolstering State and Local Care Infrastructure with Federal Recovery Funding,” New America, April 26, 2023, https://www.newamerica.org/new-practice-lab/briefs/state-and-local-care-infrastructure-federal-recovery-funding-arpa/.

- Ibid.

- Julie Kashen, “Child Care for Working Families Act Reintroduced as Need for Care Options Soars,” The Century Foundation, April 27, 2023, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/child-care-for-working-families-act-reintroduced-as-need-for-care-options-soars/.

- “ARP Child Care Stabilization Funding State and Territory Fact Sheets,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration of Children and Families, Office of Child Care, https://www.acf.hhs.gov/occ/map/arp-act-stabilization-funding-state-territory-fact-sheets.

- “State Survey Briefs,” National Association for the Education of Young Children, December 2022, https://www.naeyc.org/state-survey-briefs.

- “Young Children’s Care and Education Before Kindergarten,” National Center for Education Statistics, National Household Education Surveys Program, 2019, https://nces.ed.gov/nhes/young_children.asp.

- Julie Kashen, Julie Cai, Hayley Brown, and Shawn Fremstad, “How States Would Benefit if Congress Truly Invested in Child Care and Pre-K,” The Century Foundation, March 21, 2022, https://tcf.org/content/report/how-states-would-benefit-if-congress-truly-invested-in-child-care-and-pre-k/.

- This is similar to the approach taken in earlier TCF work, Julie Kashen, Julie Cai, Hayley Brown, and Shawn Fremstad, “How States Would Benefit if Congress Truly Invested in Child Care and Pre-K,” The Century Foundation, March 21, 2022, https://tcf.org/content/report/how-states-would-benefit-if-congress-truly-invested-in-child-care-and-pre-k/.

- Clive Belfield, “The Economic Impacts of Insufficient Child Care on Working Families,” ReadyNation, Council for a Strong America, September 2018, https://strongnation.s3.amazonaws.com/documents/522/3c5cdb46-eda2-4723-9e8e-f20511cc9f0f.pdf. Unfortunately other data sources do not allow for an understanding of the reduction of regular hours worked among parents experiencing disruptions in child care. The Belfield estimates seem to be a reasonable expectation of work hours reductions among full-time workers and our overall estimates using this methodology make sense relative to previous TCF work.

- Daniel Feenberg, “TAXSIM,” National Bureau of Economic Research, https://www.nber.org/research/data/taxsim.

- Sarah Jane Glynn, “Millions of Families are Struggling to Address Child Care Disruptions,” Center for American Progress, June 22, 2021, https://www.americanprogress.org/article/millions-families-struggling-address-child-care-disruptions/.

- “$122 Billion: The Growing Annual Cost of the Infant-Toddler Child Care Crisis,” ReadyNation, Council for a Strong America, February 2, 2023, https://www.strongnation.org/articles/2038-122-billion-the-growing-annual-cost-of-the-infant-toddler-child-care-crisis.

- Heather Boushey and Sarah Jane Glynn, “There are Significant Business Costs to Replacing Employees,” Center for American Progress, November 16, 2012, https://www.americanprogress.org/article/there-are-significant-business-costs-to-replacing-employees/.

- Sarah Jane Glynn, “Millions of Families are Struggling to Address Child Care Disruptions,” Center for American Progress, June 22, 2021, https://www.americanprogress.org/article/millions-families-struggling-address-child-care-disruptions/.

- Julie Kashen, Julie Cai, Hayley Brown, and Shawn Fremstad, “How States Would Benefit if Congress Truly Invested in Child Care and Pre-K,” The Century Foundation, March 21, 2022, https://tcf.org/content/report/how-states-would-benefit-if-congress-truly-invested-in-child-care-and-pre-k/.

- “SAGDP1 State annual gross domestic product (GDP) summary,” U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, March 31, 2023, https://apps.bea.gov/itable/?ReqID=70&step=1&acrdn=1#eyJhcHBpZCI6NzAsInN0ZXBzIjpbMSwyNCwyOSwyNSwzMSwyNiwyNywzMF0sImRhdGEiOltbIlRhYmxlSWQiLCI1MzEiXSxbIkNsYXNzaWZpY2F0aW9uIiwiTm9uLUluZHVzdHJ5Il0sWyJNYWpvcl9BcmVhIiwiMCJdLFsiU3RhdGUiLFsiMCJdXSxbIkFyZWEiLFsiWFgiXV0sWyJTdGF0aXN0aWMiLFsiMSJdXSxbIlVuaXRfb2ZfbWVhc3VyZSIsIkxldmVscyJdLFsiWWVhciIsWyIyMDIxIl1dLFsiWWVhckJlZ2luIiwiLTEiXSxbIlllYXJfRW5kIiwiLTEiXV19 .

- “Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages,” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, September 7, 2022, https://data.bls.gov/cew/apps/data_views/data_views.htm#tab=Tables.

- “State Survey Briefs,” National Association for the Education of Young Children, December 2022, https://www.naeyc.org/state-survey-briefs.

- Includes BLS-defined occupation categories “childcare workers” and “Preschool Teachers, Except Special Education.”

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Occupational Employment and Wages, May 2022: 39-9011 Childcare Workers,” Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics, April 25, 2023, https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes399011.htm.