There remains much debate about the true transformative potential of the wave of “local” movements that have multiplied around the world during the past decade. Spain’s Indignados, Warsaw’s Municipal Campaigns, Istanbul’s Gezi Park, Tahrir Square’s organizing, Occupy, and numerous other movements have made powerful associations with “the urban.”1 City squares have been the strategic locations of protesting, while the rallying call of a “right to the city” has galvanized the imagination of scholars, United Nations agencies, nongovernmental organizations, and journalists alike. These movements diverge in the scope of their aims—some have revolutionary claims of radical national transformation and others down-to-earth aspirations for a dignified daily life. But what they share is a strong association with cities, public squares, and other urban elements. These common characteristics tie them together in a global imaginary of an anti-neoliberal sentiment.

To some, there are inherent characteristics of urban spaces that explain the trend: cities are natural sites of invention and innovation because they are open to influences and external interactions, and it is thus natural for movements to emerge within them.2 To others, the city offers the grounds on which demands for citizenship can be performed not only by reclaiming public spaces, but also by squatting on lands for a place to live, thus actualizing claims of substantive inclusion.3

While informative, these arguments do not provide sufficient evidence about the potential for political change that urban social movements bring about.4 There are several questions that remain unanswered, including how urban movements differ from earlier social mobilizations. Research is needed to determine which new voices are emerging, and how they are gendering, sexing, and racializing claims that have historically been based on questions of class. There are new forms of action to identify. How promising are “alternative models” such as the commons, or shared spaces that attempt to bypass the state as an entity and propose radical transformations? How viable are they in contexts such as Lebanon’s, where, for many, political allegiance is defined according to the sectarian networks redistributing public services?

There have likely been interesting changes in the models of local governance and the entry of new actors, in local and regional councils; these developments deserve more attention. Most importantly, academics and activists must consider what we are doing to the political—the project of change—when we focus on issues such as anti-eviction and public space protection. Are we witnessing a new form of politics, or simply reducing the political to the mere demand for elements of everyday subsistence, such as access to homes and food?

Are we witnessing a new form of politics, or simply reducing the political to the mere demand for elements of everyday subsistence, such as access to homes and food?

I do not claim to answer all these questions in this short report. Rather, I approach them by building on my direct involvement as one of the principle instigators of Beirut Madinati (“Beirut My City”), the electoral campaign launched during Lebanon’s municipal elections in 2016.5 I also draw on my experience as a currently active member in the urban-based political movement that now carries the campaign’s name. I attempt in this report to reflect on the potential of city-based advocacy as an entry point for challenging entrenched sectarian politics in Lebanon. I argue that the city, both as the stage and the material substance of political mobilization, provides important pathways in Lebanon and beyond for organizational work (for example, activism, reform movements, and voter mobilization).

More specifically, I chart two arguments for activists and others interested in political change to show why urban-based organizing constitutes a form of mobilization that is both substantive and viable for long-term political change. First, the centrality of the city in the current economic and political context makes it an ideal subject of organizing that touches on immediate everyday concerns (and thus mobilizes city-dwellers) while hitting at the heart of today’s global political challenges. Second, the proximity of city-based demands to people allows for a performative form of politics that is relatable, effective, and capable of displacing some sectarian tropes. Despite these potentials, however, significant challenges remain in Lebanon, a country where voting patterns reflect strong client–patron relations rather than the aspirations of collectivities.

The report begins with a brief overview of the context Beirut Madinati’s emergence. It then fleshes out the arguments about the movement’s significance, before concluding with a review of some of the responses to the campaign, and the movement’s limitations.

Beirut Madinati’s Emergence

Beirut witnessed its largest protests in a decade in the summer of 2015. For weeks, garbage had piled up throughout the city because the main landfill was full and the government had failed, despite years of warnings, to find a new site. The government then responded to growing protests with violence. Mobilization culminated on August 28, when tens of thousands poured into the streets calling for the resignation of the ministers of environment and the interior. The protests were led by an ad hoc coalition of small groups, among which You Stink (or Tul‘it Rihitkum) is the best known. The coalition also included organized residents from affected neighborhoods, student groups, and more.6 The piles of uncollected garbage on every corner of the city may have triggered the protests, but the movement rapidly connected the city’s failed solid waste management strategy to the embezzlement of taxpayer money, challenging more generally the cultures of corruption and sectarianism that have dominated Lebanon’s politics since the civil war ended in 1990.7 The slogan “kullun ya’ni kullun” (“all of you means all of you”) denounced the entire political class, challenging the divisions that seemingly opposed Lebanon’s political life and its citizens along sectarian lines of regional allegiance.8

The August 2015 protests succeeded in bringing together individuals and groups who had, until then, worked separately. When protesters’ demands weren’t heard, activists began to debate the next steps, with some suggesting participation in local elections. In retrospect, there was little consensus among activists about the choice of municipal elections as a worthy organizing platform. In the aftermath of the protests, I attended numerous meetings that discussed options for “the next steps.” At the time, the idea of running for municipal elections in the capital city gained little steam. Some dismissed the goal as unambitious, while others believed we needed to set the basis for a national platform that could articulate a consensus over nationally divisive political challenges (such as geopolitical issues). Ultimately, a handful of us decided our next step would be to organize around the forthcoming municipal elections. Most other activists would wait many months before coming on board with the campaign, which evolved into Beirut Madinati. Even among the core organizers of Beirut Madinati, skepticism about the viability of an urban movement as an active instigator of change remained dominant during and after the campaign. I vividly recall some of the core organizers repeatedly insisting, in the months leading to the May 2016 elections, that Beirut Madinati was just a campaign, and that it wouldn’t outlive election day. This perspective allowed these organizers to set aside what they perceived as severe divergences in opinions around major national challenges (what some might call “real politics”) for a few months, during which time we had the luxury of focusing on shared urban causes. Whether these divisions were significant or not, what is clear is that the “urban” provided a rallying cause that could bridge across multiple camps, classes, and sectarian groups. There emerged a unified vision and a coherent set of demands, in which the core message was a strategy to upgrade the urban experience by securing better services and livelihoods—ultimately, a more dignified life for the urban majorities.

Even among the core organizers of Beirut Madinati, skepticism about the viability of an urban movement as an active instigator of change remained dominant during and after the campaign.

However, setting aside divisive national questions only remained possible so long as the movement was small, perceived as unthreatening, and consequently unattractive to other possible allies. By the time Beirut Madinati’s campaign gained steam, we were courted to forge alliances—open or undeclared—either with other opposition groups looking to field candidates, or with influential figures at the neighborhood level who could add to Beirut Madinati’s candidates’ list. Several mukhtars (local representatives) running in the same elections expressed interest in forging cross-alliances. These opportunities soon became the biggest threat to the internal coherence of the campaign, as core members disagreed in their readings of the repercussions of an alignment that could be perceived by campaign supporters as a rapprochement with any of the traditional political camps. Eventually, the campaign opted not to align with any of the external groups. Some still believe this decision saved the campaign’s integrity, while others feel it cost a few seats in the current municipal council.

In hindsight, it is clear that, rather than building a new political consensus, the Beirut Madinati campaign built on earlier campaigns that had been organized in Beirut since the end of the civil war. Chief among those were urban-based claims that had been the subject of substantial mobilization since 1991. Most notably, they included the resistance to the private company Solidere’s postwar redevelopment of the historical core of the city of Beirut, as well as heritage preservation campaigns, anti-highway movements, and campaigns for public space and rent control. Among the early organizers were also activists involved in secular causes—including students’ groups. However, as the campaign gained visibility, it attracted members of a vibrant civil society, one that supports cultural life, women’s rights, LGBTQ rights, the rights of people with disabilities, and others. It also brought on board many of the activists who had strived to restore the democratic electoral system in the postwar era, including some from movements demanding the restitution of local elections and those working for the transparency of elections.9

Yet Beirut Madinati also introduced a different dimension to these mobilizations, because it shifted the position of the mobilizers from activists to political agents decisively challenging the ruling elite by directly participating as contenders in the elections. Earlier mobilizations either formulated collective challenges as demands or pressure to be granted by politicians, or positioned themselves as “objective observers” monitoring due process. But Beirut Madinati nurtured a viable political alternative carried out by a coherent group of what were repeatedly described as “competent” and “honest” candidates. Until then, challenges in political alignments had happened through the work of influential individuals, never through a political platform.

In this context, it is not surprising that once the elections were over, Beirut Madinati was difficult to hold together, despite the fact that its message had garnered more than a third of the city’s votes. On the one hand, ordinary city-dwellers’ popular expectations of the movement pressured the activists to play a role they were neither institutionally capable of nor personally prepared to take. While many of us had set our professional and personal lives aside and volunteered as full-time organizers for the duration of the campaign, we were forced to return to some normalcy after the elections. However, what was often depicted as individual rifts or, more generously, activist burnout, masked more profound tensions that had emerged during the campaign—both about the modes of organizing and the consequences of Beirut Madinati’s mobilization for the political landscape. Was a challenge to the Beirut municipal council a seed to develop a secular, independent country with a new political platform? Or did it instead just destabilize the delicate balance of the political elite, perhaps favoring the ever-more-powerful Hezbollah by weakening its Beiruti rival, the Future Movement?

As national elections approached, the choice of who a possible national campaign would align with and how it would approach national challenges (such as the war in Syria, or Hezbollah’s weapons) became even more divisive. Interestingly, the divide was not about how to respond to these challenges, where most members typically allied, but on whether it would be possible to run without making them the core elements of one’s campaign. In other words, it was unclear whether the urban-based discourse of Beirut Madinati could form sufficient substance for national politics. Many of Beirut Madinati’s activists preferred to separate urban causes from national platforms, and several began campaigns outside the organizational core of the movement.

This skepticism had some resonance in the city, where movement supporters sometimes disagreed on whether running for national elections was a good decision or not, given the urban-based language of Beirut Madinati. Still, there seemed to be overwhelming support for Beirut Madinati to field candidates.

The skepticism about the potentials of an urban-based movement in forming the base of a collective political identity makes it imperative to reflect more generally on the potentials and limitations of this form of organizing, as we consider alternatives to the dominant frameworks for thinking about collective identities and mobilizations. In the next section, I present a framework for thinking through the potential of urban-based movements, before turning to an analysis of Beirut Madinati.

Urban City-zenship as a Framework

The proposition that collective belonging and organizing can be based on shared residency rather than national identity likely precedes any other forms of space-based political organizing. Often traced back to the Greek polis, early formulations of urban citizenship—or “city-zenship”—were built on the model of Greek democracy (incomplete as it may have been), in which male property owners assembled as political subjects to collectively decide on the government of their settlements.10 This model, Hannah Arendt argued, assumes that rather than living together simply by convenience or necessity, people also assemble to speak and act together—in other words, to act as political agents.11 Until the rise of the state model as a universal form of citizenship in the twentieth century, the idea of equating the city to an organized society dominated the work of many social thinkers, who treated urban settlements as the mirror of social life.12

Displaced by the dominance of the national scale over the last century, city-zenship was repopularized in recent decades by at least two trends. First, the “rolling back the state” paradigm that gained popularity among the development recipes of international organizations in the 1980s was followed in the 1990s by the decentralization mantra, which emphasized the role of local authorities in the government of territories and their people.13 Dominant debates in the fields of politics, planning, and geography, as well as policy recommendations issued by global agencies, revalorized cities as a scale of governance and emphasized the place of local authorities as democratic managers of urban jurisdictions, as well as entrepreneurial agents working to attract global investments to their cities (rather than to their nations). Participatory budgeting and public hearings produced important support for inclusion, particularly in cities with heightened mobility, engaging a debate about who gets to vote and how. In the Middle East, where the distance between decision-makers and citizens is notoriously wide, local authorities gained particular academic and activist attention. This was especially the case after the Arab uprisings brought to the fore the imperative of more democratic government (in claims, if not in practice).

In addition, cities gained importance as spaces of popular mobilization because of their centrality to the current neoliberal project. As eminent sites for the absorption of foreign and local investments, urban lands were at the heart of the ongoing financialization of the global economy.14 The growing value of urban land often occurred at the expense of the (critical) social roles that land plays as a basic ingredient for shelter, workspace, and play—and consequently damaged the possibility of dignified livelihoods for most city dwellers. Many cities of the Global South, including Middle Eastern cities like Beirut, Amman, Istanbul, and Cairo, have seen their economies shift to construction and real estate, where the city is the prime site for value extraction and capital accumulation. More generally, as the scholars Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri have eloquently put it, the city became “to the multitude what the factory was to the industrial working class.”15

As eminent sites for the absorption of foreign and local investments, urban lands were at the heart of the ongoing financialization of the global economy. The growing value of urban land often occurred at the expense of the (critical) social roles that land plays as a basic ingredient for shelter, workspace, and play.

In this context, there has been a return to city-zenship, powerfully marked by the revival of Henri Lefebvre’s famous “right to the city,” a slogan the French philosopher introduced in 1968 that has conquered the imagination of scholars, activists, and international organizations over the past few decades. Lefebvre imbued his concept, in its original formulation, with a disruptive potential that entailed emancipation from both market and state rules. In more recent uses, the slogan has been stripped of these implications. But it nonetheless retains a sense of a particular scale of political organizing that emphasizes residency within spaces marked by density, diversity, and mobility as the basis of a “being together” and the formulation of collective demands irrespective of national citizenship or legal residency status. Urban citizenship is often used to recall a status of membership—formal or informal—in a geographically defined polity. There are several substantive demands typically associated with this polity. These demands are for things, such as the right to housing, that are currently threatened by the exclusive models of urbanization that result from dominant trends in the global economy (such as urban renewal and the financialization of land).

One of the most common dimensions of the multiple existing formulations of urban citizenship is the emphasis on process over status in the conceptualization of the term.16 Thus, the political geographer Oren Yiftachel has argued that urban city-zenship denotes “a struggle enmeshed in the materiality, identities and politics of urban life, rather than in the legal and bureaucratic realms of state institutions.”17 Urban citizenship, then, is not a right passed by birth or through clearly defined legal steps. Rather, it is a claim put forward through the actions that individuals and groups take to gradually exploit opportunities made available to them in the city, or to forge new ones through what sociologist Engin Fahri Isin has termed “acts of citizenship.”18 Squatting on a piece of land to build a house, for example, or resisting segregation and demanding access to services, amounts to reclaiming the right to access spaces and places. It is thus an act of city-making that anthropologist James Holston calls an “insurgent citizenship.”19 Similarly, “struggle plumbers and electricians” in Durban, South Africa reconnect clients who are unable to pay the bills to the city’s main network, affirming their rights as city-zens rather than as clients.20 Elsewhere, in the cities of the North, others have argued that participation in protests publicly reclaiming one’s rights to live without criminalization turns being a refugee or illegal migrant into a form of reclaiming belonging or urban citizenship.21

Urban citizenship, then, is not a right passed by birth or through clearly defined legal steps. Rather, it is a claim put forward through action.

Isin is likely the most prolific writer on urban citizenship. While he argues that urban citizenship should not be construed as the alternative or opposite to national belonging, he emphasizes that this form of citizenship invokes an alternative repertoire of actions that substitutes squatting and protesting for the officially sanctioned channels. “Whereas citizenship practices like voting, paying taxes or learning languages appear passive and one-sided in mass democracies, acts of citizenship break with repetition of the same and so anticipate rejoinders from imaginary but not fictional adversaries.”22

Even with this theoretical perspective, it is not necessarily clear that voting is an effective, mundane act of citizenship everywhere, or that it cannot be construed as an act of resistance. Making such a judgment requires assessing “opportunities” to vote and the identification of movements that embody one’s perspectives. Through the experience of Beirut Madinati, I hope to build on the literature on urban citizenship to emphasize the importance of “everyday experiences” and performative mobilization in the formation of political subjectivities and collectives.

The Urban as Substantive Claim

In Lebanon, where politics is notoriously associated with corruption and derided as “dirty” (including labor movements and syndicates that are powerfully penetrated by sectarian politics), the daunting challenge for Beirut Madinati was to convince voters of the possibility for change through the ballot box.23 Success was limited on that front, with fewer than 20 percent of voters casting ballots in the 2016 elections. But the movement’s main achievement may have been to refocus the political debate during municipal elections (and to some degree, since then) toward what Beirut Madinati defined as a people-centered politics: everyday livelihoods in a productive collective assembled around the city as a basis of its organization. By advancing in text and images the possibility of living together within a frame of improved daily lives, Beirut Madinati attempted to persuade citizens of the possibility of engaging in the political process by going beyond the “declaration of wrong.”24 In other words, its campaign went beyond denouncing sectarianism, identity politics, or corruption to focus on the substantive dimensions of city-zenship and the rights of city-dwellers to live in dignity. This materialized in a road map, Beirut Madinati’s ten-point program, which served as the core substance of the campaign’s rhetoric. The movement fueled hope by helping city dwellers imagine the possibility of an alternative to the current context, energizing audiences with images and videos of brighter cityscapes. The success of the message was particularly relevant for denizens of Beirut, who had seen the quality of their lives sharply deteriorate over the past decade, and who widely associated that deterioration with the corruption of their elected representatives. And since a lot of Beirut Madinati’s early supporters were from the relatively well-off middle classes, they could immediately relate to the deteriorating urban conditions as a primary concern—perhaps more so than the working class, who might have been more concerned with survival.

Beirut Madinati’s campaign went beyond denouncing sectarianism, identity politics, or corruption to focus on the substantive dimensions of city-zenship and the rights of city-dwellers to live in dignity.

The movement’s substantive program could also be linked to a critique of the economic order since, as discussed above, the city is at the heart of the neoliberal project.25 In Lebanon, the postwar era had intensified speculative practices of land management, the privatization of shared and public spaces, the consolidation of property in the hands of a few, and its financialization after the 2008 crisis.26 Many city voters had been displaced to the suburbs by the unaffordable cost of housing, while others struggled to keep a business afloat despite hefty rents. The fact that the city is central to the logic of neoliberal capital meant that mobilizing around the city was, necessarily, also a mobilization against the logic of the neoliberal context. Activists and their supporters were reclaiming the social value of land and, more generally, the city as a space to make a livelihood: a place of employment, and a place to build one’s life.27

Aside from the content of the program, the language of the campaign allowed an engagement with politics that tried to appeal more widely, and discarded the typical tropes of sectarianism and the esoteric vocabulary of journalists and politicians. Beirut Madinati spoke of everyday needs (like traffic jams and the housing crisis) or health concerns (such as water and air pollution) and encouraged city-dwellers to join in demanding the substantive rights they should be able to claim on the basis of their residency or belonging. In doing so, the movement made the “political” accessible. One didn’t require prior knowledge of the complicated history and backgrounds of public figures nor a command of the jargon of sectarian power sharing to express support for a movement that spoke a young, refreshing, and accessible language, and called on city-dwellers to get involved with challenges derived from their everyday experiences.

Beirut Madinati projected an alluring image on social media of a “young movement.” The movement’s candidates wore casual outfits rather than suits, and relied on vernacular Arabic and street slogans. They consistently represented equality across sexes, and occasionally alluded to the support of LGBTQ rights. They repeatedly invited supporters to participate in their conversations through numerous accessible opportunities—share a post, take a picture, film a video. This approach particularly appealed to a younger crowd, which soon flocked in droves to Beirut Madinati’s headquarters to offer support. On social media, individual responses were equally abundant, with numerous visuals, messages, videos, animations, and GIFs posted daily by people eager to show support, even if they lived abroad. This was part and parcel of the branding and design of the communication campaign, which embraced collaboration: keeping a strong logo while allowing decentralized production and a large variety of ways to participate, including neighborhood debates.28

Despite the recognition that poor living conditions were derived from the dominance of finance and the reliance of the political class on sectarian interests to maintain its hold, campaign messaging mostly focused on strategies for the spatial and social upgrading of the city, on its faith in the experiences of the more than forty experts who wrote Beirut Madinati’s platform, and on the capability of the candidates to implement it. The positive response to this approach is perhaps best evidenced by the fact that, for the first time in the postwar period, the establishment-backed list issued “an electoral program” two weeks before the elections, listing interventions it would implement in the city. These included green spaces, better mobility, and more. Many of these interventions were borrowed directly from Beirut Madinati’s program, instantly triggering a critical “#copy_paste” response campaign that went viral on social media.

In sum, the city provided the substance around which it was possible to campaign with an accessible, inclusive language. The claim of a “right to a dignified life in the city” was eventually seen as part of the “performance” of the political, one that focused on the substantive dimensions of city-zenship rather than the status of citizenship bestowed by one’s birthright and enmeshed in local power divisions. I turn now to this performative aspect.

City-zenship as a Disruptive Claim

Beirut Madinati was an official electoral campaign. At its outset, its activities fit within the classical repertoire of citizen activities, such as campaigning or voting. Yet the campaign and the movement that later carried the name borrowed strategies from disruptive actions or protest, activating the performative dimensions of citizenship. These performative dimensions can be classified in two categories.

First, the movement relied on “theatrical acts” that evoked the possibility of a democracy. In part, this was a necessity, because community organizing was difficult with meager resources and limited access to some of the city’s neighborhoods, where strongmen opposed our presence or even campaigning altogether. Thus, Beirut Madinati invested in the image of a democratic movement put forward first in social media, and later through the country’s main news outlets, as interest in its activities grew. The campaign’s candidate list was a colorful palette of architects, city planners, engineers, doctors, artists, lawyers, and a fisherman. These candidates inspired change on their own merit, which was significant: while city-dwellers had been accustomed to thinking of every candidate as a “representative” of a specific political party and sectarian group, the candidate list of Beirut Madinati was coherent and professional. Its members’ identities were based on their personal trajectories and public involvement, brought together around a consolidated program of urban change. In addition, half the candidates were women, affirming equality in a patriarchal society where feminine representation is dismal. The diversity of their professional backgrounds provided an additional aura of inclusivity that is unusual in Lebanon. Candidates included the acclaimed actress Nadine Labaki; the popular musician Ahmad Kaabour; the head of the fishermen’s cooperative in one of Beirut’s districts, Najib el-Dik; and Amal al-Shareef, a long-time defender of the rights of people with disabilities who herself uses a wheelchair. There were also public debates in which the group went to the streets to meet neighborhood residents and discuss with them the everyday challenges in their quarters. A talented young actor accompanied these visits, and managed to turn them into visible public performances that attracted the media’s attention despite the fact that the number of residents who participated was often not terribly large. It allowed the group to advance its agenda of street-level mobilization, which was widely acclaimed and bestowed on the campaign an aura of effective grassroots mobilization.

Second, Beirut Madinati challenged the rules of the electoral game, particularly the sectarian and regional classifications through which Lebanese citizens must typically channel their representation. In Lebanon, citizens are generally required to vote in the area of their family’s origin, both in local and national elections. While it is legally possible to transfer one’s registration, heavy administrative barriers make it difficult if not impossible to process such demands.29 As a result, local elections are not representative of the city’s actual residents, particularly in large cities such as Beirut, where population mobility rates are higher. Most of the city’s residents are not even eligible to vote in local elections. Compounding the problem, prohibitive land costs in the capital city have pushed many of the would-be eligible voters outside of administrative boundaries. Local elections thus reproduce the sectarian balance defined along historical territorial divisions, by keeping a relatively stable body of voters in each locality.

Beirut Madinati challenged the rules of the electoral game, particularly the sectarian and regional classifications through which Lebanese citizens must typically channel their representation.

Beirut Madinati disrupted this reality by making public displays of political instigation that involved urbanites who could neither vote nor run for Beirut’s municipal elections. This was a challenge to the rules of Lebanon’s local electoral politics, effectively highlighting the absurdity of the sectarian boundaries of political representation. To give just a few examples, none of the original campaigners were from the traditional “city families”—those “native” Beirutis who trace their urban pedigree to colonial times or earlier. What’s more, most didn’t even vote in Beirut. This included the campaign coordinator, the campaign’s lawyer, and the program and communication coordinators. While all of us were born and raised in Beirut and identified with it as our city, none of us was eligible to run or vote in our hometown. Further, during the first public launch of the movement, four of the five presenters were not eligible to participate in Beirut’s elections. This situation might have caused us to shrink from direct involvement in local politics—and indeed it has done exactly that for most people for many years. But instead, the campaigners sought to amplify the irony of their positions, flaunting the message that reclaiming a livable city through an electoral campaign amounted to more than just garnering votes. All in all, one can safely estimate that more than half the campaign organizers and its supporters were not eligible to directly participate in Beirut’s elections. Yet their involvement in thinking, messaging, registering voters, fundraising, and other aspects of the campaign challenged the limits of who can speak for and about the city, and who can be involved in local politics.

The visible display of this participation outside the vote recalls other acts of performative politics where the significance of the political engagement rests in the visible enactment of the challenge. This allows a discussion of political engagement with a focus on the actual “acts” that each individual is willing to undertake, and moves beyond the depiction of society in the binary terms of citizen and noncitizen.30 For example, political scientist Monica Varsanyi has described protesting by undocumented migrants in the United States as a process through which these individuals become visible, reclaim public squares, and demand the right to make claims as citizens.31 Similarly, sociologist Thomas Swerts has described the protests of undocumented migrants in Canada as the theatrical and performative staging of citizenship in which undocumented migrants demonstrate to the world that they are “citizens in practice.”32 While they may not be asking for membership to a state, these illegal migrants are performing acts of citizenship, acts through which they create new “scripts” of what it means to be a citizen. These acts may supersede traditional definitions of citizenship.33 In Beirut Madinati’s campaign, the “performative” expressions of urban citizenship contested the distribution of rights, privileges, and places through which regional territorial (read: “sectarian”) populations are governed.34 Instead, new configurations of political membership that rest on the place of residence were put forward. Clearly, these configurations were incomplete—they could not grant substantive rights to city-zens, nor could they empower those engaged in Beirut Madinati who were legally ineligible to actually run or vote for the campaign. Yet they formed an “engagement with citizenship” or city-zenship that ultimately challenged the structures of representation. These are, in the words of the scholars Maria Kaika and Lazaros Karoliatas, “alternative ways of imagining, doing and saying in common.”35

Beirut’s administrative limits are a carefully studied and organized political electoral map that largely secures the electoral outcomes to those who define the boundaries.

In that same spirit, Beirut Madinati’s program also transgressed the administrative boundaries of the city limits by putting forward its vision for Lebanon’s capital city. Space is central to the reproduction of the forces that organize society. It is particularly important for sectarianism, which forms and reshapes much of Beirut’s urbanization and spatially materializes in the divisions of administrative and voting jurisdictions that strengthen and reproduce the vertical patron–client system. Beirut’s administrative limits are a carefully studied and organized political electoral map that largely secures the electoral outcomes to those who define the boundaries.36 This dissection of the city in territorial sectarian units is, Beirut Madinati’s platform pointed out, specifically what explains the city’s poor services: an integrated territory through which populations flow relatively seamlessly is governed by rival sectarian political groups whose interest is the control of their populations, rather than the services of the city.37 As a result, an electoral program that outlines in its preamble the impossibility of servicing the city and addressing its failing infrastructure without coordinating at the regional scale is an implicit challenge to sectarian territoriality—without frontally attacking the topic. How could, for example, a municipality governing Beirut within its administrative borders facilitate traffic flows, when 70 percent of the cars that drive through the city actually come from outside these borders? How can it manage the sewer network when treatment plants are outside its boundaries? Unless territories are linked, recognizing the integrative nature of infrastructure, the city will remain ungovernable. Beirut Madinati’s program and candidates argued that, before urban services could be improved, there was a need for a different form of politics that rests on the common residency in the greater capital area, instead of the current sectarian territoriality.

Responses and Limits

Beirut Madinati’s success in attempting to shift the municipal elections toward a struggle over who gets to reclaim the city is perhaps best assessed in the reaction of the political elite. Despite a heavily polarized political environment, a coalition bringing together the full spectrum of the political elite coalesced in a unified list against Beirut Madinati. The establishment-backed list branded itself as the “Beirutis” (the people from Beirut). This naming might seem innocuous to outsiders, but in the context of Beirut, where claims to indigeneity have such specific political implications, it was something of a dog whistle—a “defensive” posture of urban citizenship.38 It even recalled anti-immigrant movements where racialized fears are raised against “newcomers” even when the latter have resided in the city for decades. The minister of the interior at the time, Nohad Machnouk—who hails from a strong Sunni Muslim family of Beirut—directly orchestrated the campaigning, reminding assembled voters at every occasion of the necessity to “defend” the city from “outsiders.”

“Voting for the Future Movement’s electoral list will protect the capital from the lists of opponents who wish to break the city and its decision,” Machnouk said one Sunday, in a brunch meeting with voters.39 Beirut Madinati and its supporters didn’t belong to the city, they had no right to speak in its name. Rather, they were here to “break” the city. “It is the first time we say that voting is in defense of the city, something which was never mentioned in any previous elections,” Mashnouk said at the end of the brunch speech.

Beirut Madinati and its supporters didn’t belong to the city, they had no right to speak in its name. Rather, they were here to “break” the city.

This type of rhetoric would become very common in the following weeks, as establishment politicians struggled to reclaim the local, divisive, and sectarian organization of representation. In this frame, the challenge posed by Beirut Madinati was a direct affront to the Sunni leadership that was entrusted with the control of the city, and particularly to the prime minister, Saad Hariri, heir of the late Rafik Hariri and the Sunni leader of Lebanon.40 The establishment’s reaction culminated in a large-scale rally held in a large basketball arena and attended by Hariri, who returned from France to Beirut after months of self-imposed exile in emergency to defend his coalition’s rule over the city. At the event, a stereotypical character known as Umm Khaled, a supposedly “typical Sunni Beiruti woman,” was played by Lebanese actress Joanna Karaki, who welcomed the leader of the sectarian community and reaffirmed in strong and colorful rhetoric his unchallenged rule over the city.41 This rhetoric, in turn, generated a powerful debate about who has the right to claim the city. On the one hand, there was a camp that expressed outrage at what they saw as racist, sectarian discrimination against the majority of city dwellers who couldn’t trace back lineage to the large Sunni families of Beirut and rejected what they described as a provincialization of the capital city. On the other were those who bluntly rejected the claim of a political right to the city by virtue of residence. After all, they said, no “Beiruti” voter would be voting in these impostors’ home districts.42 This opposition was not limited to the Sunni community. Rather, the guardians of the sectarian power-sharing orders of Lebanon, including prominent TV anchor Marcel Ghanem, didn’t hesitate to attack the mobilization as threatening “national coexistence”—an allusion to the risk that Beirut Madinati might shift any of the informal agreements on the sectarian composition of the electoral list. Similarly, Hariri repeatedly expressed his alarm at the movement threatening the so-called Muslim–Christian “parity” in the government of the city.43

Taking the Model beyond Beirut

In sum, Beirut Madinati managed to display a performance of citizenship that disrupted the organization of the political dividing lines by claiming a voice within the electoral process but outside the rules of this process, as it is defined in Lebanon. We addressed the constituent order itself: we were not simply asking for housing but actually calling into question who can ask for housing, and where. Eventually, the electoral list complied to the rules of the game by maintaining sectarian parity. The actual mobilization, however, challenged this form of political representation by appealing to the dream of a “collective” and the imagination of a possible future embodied in the vision advanced by the movement of the city that might be. It is this performative, theatrical dimension that energized Lebanon’s political scene and will remain, I believe, one of the most enduring achievements of Beirut Madinati.

In a recent attempt to theorize the politicizing of the city, the academics Mustafa Dikeç and Erik Swyngedouw recall Michel Foucault’s formulation of the “people” as those who disrupt the system by refusing to be a “population.”44 The last decade has shown that this process of politicization doesn’t require a pre-consolidated, internally coherent political entity, but rather congeals through acts of collective mobilization.45 The act of interrupting the “order of the sensible” that recent urban insurgencies produce, Dikeç and Swyngedouw argue, facilitates the coming together of a collectivity of heterogeneous individuals and allows them to become political subjects. “The heterogeneous socio-spatial positionalities of participants and their various forms of social relating, bonding, engagement and organization,” they write, “shift the terrain from particular forms of social mobilization and action to universalizing claims for democracy, freedom and solidarity, marking a shift away from social to political movement.”46

Herein lay the importance of You Stink for the formation of Beirut Madinati, but also the effect of Beirut Madinati in mobilizing numerous activists to participate in politics. Thus, in the weeks following Beirut’s municipal elections in 2016, local elections held in other districts witnessed the rise of small-scale electoral movements energized by the model of Beirut Madinati. Some of them—such as Baalbek Madinati (from a city in the Beqaa Valley)—directly translated the name of the Beirut municipal campaign. Others only replicated some of its approaches. In the months leading to the national elections in 2018, numerous movements and campaigns inspired by Beirut Madinati emerged, hoping to record a similar success. These movements reflected a desire for the formation of collectivities that could speak on behalf of the people and—recalling Dikeç and Swyngedouw—to demand a democratic government and sound economic strategies.

In the weeks following Beirut’s municipal elections in 2016, local elections held in other districts witnessed the rise of small-scale electoral movements energized by the model of Beirut Madinati.

Divided over organizational issues and political readings of national conditions, Beirut Madinati members refrained from running under its banner in the national elections. Many nonetheless directly participated in national elections in other ways: several ran for office, and others coordinated campaigns. In the organizational work that forced them to address national challenges, however, such as how to address the presence of armed groups in the country or how to position themselves in relation to geopolitical alliances, the electoral movements who participated in the 2018 election campaigns appeared frail. Their discourse was either too shy in relation to the establishment’s, or too grand to be convincing. Eventually, the coalitions they formed at the national scale were marred by internal disagreements about the vision for the country, what would constitute a viable long-term strategy for national development, and who among their members would qualify to run for office. In the absence of a credible story to tell—such as the powerful narrative of a well-functioning city that Beirut Madinati could convincingly bring to its constituency—it was impossible for these platforms to shift the debate away from the terrain of sectarian divisiveness and toward the imagination of a new form of collectivity, such as that promised by city-zenship.

What country did they aspire to live in? What would be its national pillars? How would they address regionally fueled sectarian tensions? How would they control local armed groups such as Hezbollah, whose military actions in the region went well beyond national borders? Few workable strategies to respond to these challenges were put forward. This was partially because the questions were clearly unsolvable by the terms of the debate, but also—I speculate—because these grassroots opposition groups mostly stuck to the same platforms as established political parties, and often remained confined within the geographic districts imposed by electoral maps, where participation was pre-engineered to fail them. They consequently remained unable to project a viable alternative, even when they presented more convincing options both through the profiles of some of their candidates and the content of their rhetoric.

In its theatrical national appeal, Kulluna Watani (We Are All Our Nation), the coalition launched a month before election day in April 2018, may have provided the most faithful attempt to replicate Beirut Madinati’s experience. It built on the principle of a collective national imagination to propose one national umbrella or coalition group that would field candidates from nine different districts of Lebanon.47 But it was practically absent on the ground in several of these districts, and Kulluna Watani failed to inspire the way Beirut Madinati did. Lack of internal coherence led some of the individuals and groups running under its banner to strengthen their own independent brand rather than melt into the group. It didn’t help that the coalition had no running lists in some of the main districts—most damagingly, in the “Muslim” half of administrative Beirut, where nine contending lists competed over the seats. An analysis of Kulluna Watani’s inability to mobilize is outside the scope of this essay. But whatever the problem was, the translation of the city’s experience to the national scale was clearly less seamless than some of the activists had hoped.

The Future of Politics in the City

Conversely, a number of established politicians, inspired by Beirut Madinati’s success, used the themes of the city in order to formulate campaign programs, this time appropriating the “urban” for their own agendas. Most prominently, Nicolas Sehnaoui, a member of the Free Patriotic Movement, developed a vision of his Beirut district complete with urban design visualizations that he promised to implement.48 But while Beirut Madinati had used the “urban” as a language of unification, showing the necessary interrelatedness of urban districts beyond administrative jurisdictions, Sehnaoui’s plans reversed the use of the “city” and limited its use to beautification measures in the Christian quarters of Beirut where he was running. His campaign lacked any of the disruptive motives of Beirut Madinati. Disruption was, anyway, hardly Sehnaoui’s intent; he was instead keen on energizing the young electorate of his district with pleasant images of their city’s future, rather than inspiring a new form of collectivity.

As the dust settles from the 2018 national elections, and various activist groups assess their ability to consolidate into long-term political formations, the appeal of the city as an organizational unit is more powerful than ever.

As the dust settles from the 2018 national elections, and various activist groups assess their ability to consolidate into long-term political formations, the appeal of the city as an organizational unit is more powerful than ever. The pressure placed on Beirut Madinati to formulate positions on geopolitical issues as part of a credible national political alternative may have been misplaced: many of the national political parties also failed to present convincing options. Meanwhile, a handful of Beirut Madinati members who remained active in the organization have begun to demonstrate the possibility of consolidating the campaign into an actual political organization. Following months of exchanges with other grassroots movements—including two visits from a member of the Spanish political party Podemos—the organization has set up two successful neighborhood groups. These groups have each built a grassroots presence in a city district and played a vocal role as advocates of issues related to urban mobility, waterfront development, waste management, and others. Beirut Madinati has also inscribed itself as part of the loose national coalition of opposition movements, participating in collective protests and statements while keeping a distinct voice on city-based issues.

It should be recognized, however, that even if a city-based platform managed to empower the formation of a political movement consolidating urban-based demands, its ability to destabilize the sitting sectarian order remains limited. No matter how appealing a political platform is—and I believe that the three years since the elections have amply demonstrated its possibility—it can only translate into an actual voting pattern when and if city dwellers come to the ballot box to express the appeal of the platform rather than allegiance to a patron. This, in turn, requires a reformulation of the terms of citizenship in the country, away from clientelism. The task is daunting as long as the current economic crisis makes the redistribution of state goods through sectarian channels the only survival strategy for many.49 Consequently, the engagement of city-zens may not transform the results at the ballot box, at least in the short run. Yet one can predict with confidence that the idea of the collective that it has advanced can indeed form the basis of collective organizing and mobilization, and force a repositioning of electoral debates and policymaking on issues of vital importance.

This policy report is part of Citizenship and Its Discontents: The Struggle for Rights, Pluralism, and Inclusion in the Middle East, a TCF project supported by the Henry Luce Foundation.

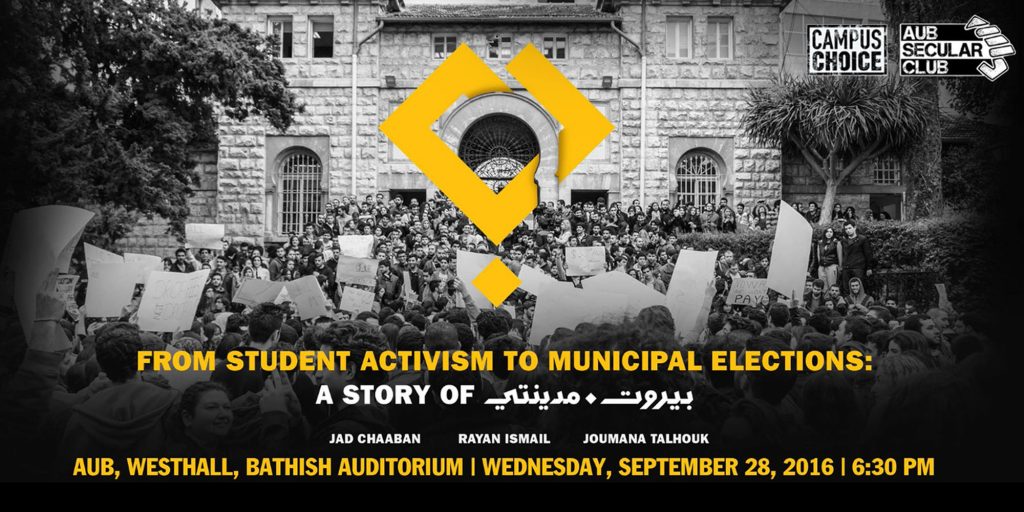

Cover Photo: Thousands march against the sectarian system in Lebanon on March 6, 2011 in Beirut. Source: Mohamad Cheblak/Flickr

Notes

- On the Indignados, see Sophie Gonick, “Indignation and Inclusion: Activism, Difference, and Emergent Urban Politics in Postcrash Madrid,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 34, no. 2 (2016): 209–26. On Warsaw’s Municipal Campaigns, see Anna Domaradzka, “Changing the Rules of the Game: Impact of the Urban Movement on Public Administration Practices,” in Civil Society and Innovative Public Administration, ed. Matthias Freise, Friedrich Paulsen, and Andrea Walter (Baden-Baden: Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, 2015), 188–217. On Istanbul’s Gezi Park, see Sinan Erensü and Ozan Karaman, “The Work of a Few Trees: Gezi, Politics and Space,” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 41, no. 1 (2017): 19–36. On Tahrir, see Mustafa Dikeç and Erik Swyngedouw, “Theorizing the Politicizing City,” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 41, no. 1 (2017): 1–18. On Occupy, see Margit Mayer, “The ‘Right to the City’ in Urban Social Movements,” in Cities for People, Not for Profit, ed. Neil Brenner, Peter Marcuse, and Margit Mayer (New York: Routledge, 2012): 75–97.

- Ash Amin and Nigel Thrift, Cities: Reimagining the Urban (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2002); Jenny Robinson, “Inventions and Interventions: Transforming Cities—an Introduction,” Urban Studies 43, no. 2 (2006): 251–58. Specifically in relation to Beirut, see Stephen Deets, “Consociationalism, Clientelism, and Local Politics in Beirut: Between Civic and Sectarian Identities,” Nationalism and Ethnic Politics 24, no. 2 (2018): 133–57

- See Faranak Miraftab and Shana Wills, “Insurgency and Spaces of Active Citizenship: The Story of Western Cape Anti-Eviction Campaign in South Africa,” Journal of Planning Education and Research 25, no. 2 (2005): 200–217; Engin Fahri Isin, “Introduction: Cities and Citizenship in a Global Age,” 1999; Arjun Appadurai and James Holston, “Cities and Citizenship,” Public Culture 8, no. 2 (May 1, 1996): 187–204; and Dikeç and Swyngedouw, “Theorizing the Politicizing City.”

- Margit Mayer, “First World Urban Activism: Beyond Austerity Urbanism and Creative City Politics,” City 17, no. 1 (2013): 5–19.

- Earlier studies on Beirut Madinati include Mona Khneisser, “The Marketing of Protest and Antinomies of Collective Organization in Lebanon,” Critical Sociology, 2018, 0896920518792069; Thanassis Cambanis, “People Power and Its Limits: Lessons from Lebanon’s Anti- Sectarian Reform Movement,” The Century Foundation, March 29, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/report/people-power-limits; Deets, “Consociationalism, Clientelism, and Local Politics in Beirut;” Mona Harb, “New Forms of Youth Activism in Contested Cities: The Case of Beirut,” The International Spectator 53, no. 2 (2018): 74–93; and Deen Sharp, “Beirut Madinati: Another Future is Possible,” Middle East Institute, September 2016, https://www.mei.edu/publications/beirut-madinati-another-future-possible.

- Konstantin Kastrissianakis, “Exploring Ethnocracy and the Possibilities of Coexistence in Beirut,” Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: An Interdisciplinary Journal 8, no. 3 (2016): 59; Sharp, “Beirut Madinati.”

- See Jeffrey G. Karam, “Beyond Sectarianism: Understanding Lebanese Politics through a Cross-Sectarian Lens,” Brandeis University Middle East Brief no. 107, April 2017, https://www.brandeis.edu/crown/publications/meb/MEB107.pdf; Bassel Salloukh, et al., The Politics of Sectarianism in Postwar Lebanon (Cambridge: Pluto Press, 2015).

- Since 2005, Lebanon’s political class has been split in two alliances: March 8 (referring to the allies of the Syria–Iran regional alliance) and March 14 (referring to anti-Syrian protesters, typically seen as the allies of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and Western countries). The March 8 alliance includes the Shiite political parties, the March 14 the Sunni political parties, while Christian and Druze parties are mostly split between the two. These alliances are far from set in stone, as recently demonstrated in national elections where they ran on similar electoral lists in many jurisdictions. Yet the balance of these blocks is critical to the perpetuating of the current political situation, in which all decisions can be halted until bargaining among them secures some level of perceived equality—as recently happened with the nine-month delay for the formation of a cabinet.

- On these campaigns, see Harb, “New Forms of Youth Activism in Contested Cities,” 2018; Saree Makdisi, “Laying Claim to Beirut,” Critical Inquiry 23 no. 3 (1997): 661–705; Sharp, “Beirut Madinati”; Abir Saksouk-Sasso, “Making Spaces for Communal Sovereignty: The Story of Beirut’s Dalieh,” Arab Studies Journal 23, no. 1 (2015): 296; Nadine Bekdache, “Evicting Sovereignty: Lebanon’s Housing Tenants from Citizens to Obstacles,” Arab Studies Journal 23, no. 1 (2015): 320.

- Rainer Baubock, “Reinventing Urban Citizenship,” Citizenship Studies 7, no. 2 (2003): 139–60; Monica W. Varsanyi, “Interrogating ‘Urban Citizenship’ Vis-à-Vis Undocumented Migration,” Citizenship Studies 10, no. 2 (2006): 229–49. Many others have used the term City-zenship. See, for example, Michael Keith, “City-zenship in Contemporary China: Shanghai, Capital of the Twenty-First Century?,” in The New Blackwell Companion to the City, ed. Gary Bridge and Sophie Watson (Hoboken, NJ: Blackwell, 2012): 398–406.

- Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013). See also Engin Fahri Isin, Being Political: Genealogies of Citizenship (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2002).

- Richard Sennett, Classic Essays on the Culture of Cities (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1969).

- Often related to the Thatcher-Reagan era, the expression “rolling back the state” refers to pressures placed by international organizations and transnational corporations to downsize governments, often as a precondition for assistance. See, for example, Jonathan Pugh and Robert B. Potter, “Rolling Back the State and Physical Development Planning: The Case of Barbados,” Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography, 21(2): 2000, 183–99.

- David Harvey, “Neoliberalism and the City,” Studies in Social Justice 1, no. 1 (2007): 2–13.

- Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Commonwealth, First Harvard University Press paperback edition (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2011).

- Isin, Being Political.

- Oren Yiftachel, “Epilogue—From ‘Gray Space’ to Equal ‘Metrozenship’? Reflections on Urban Citizenship,” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 39, no. 4 (2015): 726–37.

- Isin and Greg Marc Nielsen, eds., Acts of Citizenship (London and New York: Zed Books, 2008).

- James Holston, “Insurgent Citizenship in an Era of Global Urban Peripheries,” City & Society 21, no. 2 (2009): 245–67.

- Miraftab and Wills, “Insurgency and Active Citizenship.”

- Varsanyi, “Interrogating ‘Urban Citizenship;’” Thomas Swerts, “Creating Space for Citizenship: The Liminal Politics of Undocumented Activism,” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 41, no. 3 (May 2017): 379–95.

- Isin and Nielsen, Acts of Citizenship, 2.

- See Domaradzka, “Changing the Rules of the Game;” and Deets, “Consociationalism, Clientelism, and Local Politics in Beirut.”

- Jacques Rancière, Disagreement: Politics and Philosophy (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999).

- Harvey, “Neoliberalism and the City.”

- On the privatization of shared spaces, see Ussama Makdisi, “The Modernity of Sectarianism in Lebanon,” Middle East Report 26 (1996): 23–26; Najib B. Hourani and Ahmed Kanna, “Neoliberal Urbanism and the Arab Uprisings: A View from Amman,” Journal of Urban Affairs 36, sup. 2 (2014): 650–62. On the consolidation of property ownership, see Mona Fawaz, Marieke Krijnen, and Daria El Samad, “A Property Framework for Understanding Gentrification: Ownership Patterns and the Transformations of Mar Mikhael, Beirut,” City 22, no. 3 (2018): 358–74. On the financialization of property, see Krijnen, “The Urban Transformation of Beirut: An Investigation into the Movement of Capital” (PhD diss., Ghent University, 2016); Bruno Marot, “Growth Politics from the Top Down: The Social Construction of the Property Market in Post-War Beirut,” City 22, no. 3 (2018): 324–40.

- Harvey, “Neoliberalism and the City.”

- Ian Akerman, “Beirut Madinati and the Politics of Design,” Campaign Middle East, May 27, 2016, https://campaignme.com/2016/05/27/110419/beirut-madinati-and-the-politics-of-design/.

- Mona Harb and Sami Atallah, Local Governments and Public Goods: Assessing Decentralization in the Arab World (Ras Beirut: The Lebanese Center for Policy Studies, 2015); Abu-Rish, “Municipal Politics in Lebanon.”

- Isin and Nielsen, Acts of Citizenship.

- Varsanyi, “Interrogating ‘Urban Citizenship.’”

- Swerts, “Creating Space for Citizenship.”

- Swerts, “Creating Space for Citizenship.”

- Swerts, “Creating Space for Citizenship.”

- Maria Kaika and Lazaros Karaliotas, “The Spatialization of Democratic Politics: Insights from Indignant Squares,” European Urban and Regional Studies 23, no. 4 (October 2016): 556–70.

- Harb and Atallah, Local Government and Public Goods; Hiba Bou Akar, For the War yet to Come: Planning Beirut’s Frontiers (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2018); Mohamad Hafeda, Negotiating Conflict in Lebanon (forthcoming).

- See Mona Fawaz, “Urban Policy: A Missing Government Framework,” Lebanese Center for Policy Studies, May 2017, https://www.lcps-lebanon.org/featuredArticle.php?id=116.

- Yiftachel, “Epilogue.”

- Speech given in a Sunday brunch with “Beiruti families” on February 18, 2016. See “Machnouk: To Participate Heavily in Beirut’s Elections in Defense of Its Fate,” National News Agency, February 18, 2018, http://nna-leb.gov.lb/en/show-news/88365/nna-leb.gov.lb/en.

- Majd Abou-Mujahid, “This Is Why the Beiruti List Won Over Beirut Madinati” (Arabic), An-Nahar, May 12, 2016, https://www.annahar.com/article/378371-لهذه-الأسباب-فازت-لائحة-البيارتة-على-بيروت-مدينتي.

- The event was held at Nadi al-Riyadi on April 5, 2016. For more, see “In Video: Umm Khaled Finally Meets President Hariri” (Arabic), An-Nahar, April 5, 2016,

https://www.annahar.com/article/372982-بالفيديو–وأخيرا-أم-خالد-تلتقي-الرئيس-الحريري. - See, for example, Maha Huteit, “Beirut in Municipal Elections” (Arabic), New Arab, April 28, 2016, https://www.alaraby.co.uk/medianews/2016/4/28/بيروت-في-الانتخابات-البلدية.

- Hussein Dakroub, “Hariri Urges Beirutis to Vote for Coexistence,” Daily Star, May 5, 2016, http://www.dailystar.com.lb/News/Lebanon-News/2016/May-06/350823-hariri-urges-beirutis-to-vote-for-coexistence.ashx.

- Dikeç and Swyngedouw, “Theorizing the Politicizing City.”

- Adriana Kemp, Henrik Lebuhn, and Galia Rattner, “Between Neoliberal Governance and the Right to the City: Participatory Politics in Berlin and Tel Aviv,” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 39, 4 (2015): 704–25.

- Dikeç and Swyngedouw, “Theorizing the Politicizing City,” 10.

- See for example Nada Ayoub, “Kulluna Watani: Sixty-Six Candidates on Nine Lists to Build a Country of Citizens, Not Clients” (Arabic), An-Nahar, April 9, 2018, https://www.annahar.com/article/788380-كلنا-وطني-66-مرشحا-في-9-لوائح-لبناء-دولة-المواطنة-بدل-المحسوبيات.

- The Free Patriotic Movement is one of the established political parties in Lebanon, which counts the president of the republic, Michel Aoun, among its members.

- The gross domestic product of Lebanon grew just 1 percent in 2018, and is only expected to be slightly higher in 2019. “World Economic Outlook Database,” IMF, accessed March 5, 2019, https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2018/02/weodata/index.aspx. Even this paltry growth number, however, disguises the grave reality on the ground, where the economic situation is becoming more and more painful for most Lebanese. See, for example, Khalil al-Hariri, “Lower Your Expectations,” Carnegie Middle East Center, December 18, 2018, https://carnegie-mec.org/diwan/77990.