The Syrian war continues to flow back and forth, but since Russia and Iran intervened in Syria’s civil war in autumn 2015, President Bashar al-Assad has largely stabilized his position. Despite the continuing economic decay of his government, Assad’s army has managed to reverse some earlier losses and capture key areas from its enemies, notably around Aleppo. Since March 2016, Russia has limited its support for Assad, in grudging compliance with a truce negotiated with the United States. But if Russians and Iranians were to decisively put their shoulders to the wheel again, as they did in January and February, it is likely that they could further tip the scales in Assad’s favor.

There is little doubt that Assad is still hoping for a full restoration of Baathist rule. As recently as June, he vowed to “liberate every inch of Syria.” However, swallowing new territory is one thing; digesting it is another. Governing hostile populations in the midst of a civil war is a costly and manpower-intensive task. Assad already suffers from a severe shortage of soldiers, an increasingly dysfunctional administrative structure, and dwindling resources. If he recaptured lost territory, he would have trouble supplying enough soldiers, police, and administrators to rule it. If the rebels were pushed back further, they would also be very likely to turn to urban guerrilla tactics, sabotage, and bombings, making newly acquired territory even more difficult to rule.

Ultimately, Assad’s ambition to restore the pre-2011 status quo ante runs up against the enormous changes wrought by the war. In many areas, the Syrian president was able to offset his manpower shortage only by relying on local actors with decades-old ties to his regime. Where the insurgents have gained ground, these supporters have largely disappeared: some have switched sides, others have fled or been killed. Old relationships and networks that used to benefit the government have been shattered beyond repair.

This policy brief examines the northwestern provincial capital of Idlib—alongside jihadi-controlled Raqqa, it is the most important city captured by the insurgency so far—to explore how Assad previously managed to rule it by entrusting security tasks to local proxies, and why that may no longer be possible.

Syria’s future, much like Idlib’s present, is more likely to be an unstable and violent patchwork of local fiefdoms than a united country capable of healing its wounds.

The case of Idlib does not tell us who will ultimately win the war in Syria, if anyone can, or even where the city itself is headed. But it does show that Assad’s original system of population control has been ruined by his loss of the city in 2015, probably to the extent that it can never be restored. It gives us a grim glimpse of the alternatives on offer, indicating that Syria’s future, much like Idlib’s present, is more likely to be an unstable and violent patchwork of local fiefdoms than a united country capable of healing its wounds. Because, as improbable as it seems that Assad would ever be able to fully reassert control over the half Syria where his regime has been uprooted by the rebellion, none of his rivals seem any better placed to do it.

The Local Roots of the Regime

The Assad government is often dismissed as a narrowly sectarian regime based on the Alawite minority from which Assad hails. The sectarian aspect was certainly important and has become much more so since 2011, but this is a gross simplification. Though the security elite at the core of the regime is strongly dominated by Alawite families, the top of the tree was always very different from its roots.

When the conflict began in 2011, the Assad family controlled a vast network of local contacts, clients, and dependents inherited from half a century of Baath Party rule. The government did not rule Syria’s rural periphery by dispatching officers to whip the population into submission, but by incorporating them in its web of institutions and client networks, and by enticing local strongmen into mutually profitable relationships with the state. In every city, neighborhood, or little hamlet, the central government had its allies. They could be working for a ministry or for the army, for the governorate or the municipality, for the state companies that controlled so much of the economy, or for the Baath Party and its popular organizations. Provincial intelligence offices and others also maintained informal networks of agents and informers, stepping in to bark orders only when a softer touch had failed. Personal relations mattered greatly. Middlemen in the form of Baathist cadres, retired officers, men of religion, business owners, or tribal sheikhs often served as liaisons and service-providers, exploiting their personal influence over villages, families, clans, companies, charitable organizations, or even organized crime, all in service of their relationship with the central government.

This was what saved Assad when his regime stumbled in 2011: his ability to reach beyond the limits of a purely sectarian strategy and to weaponize five decades of social control.

In early 2011, these contacts were called upon to save the regime—and themselves—from the rising tide of opposition. Their followers became the nucleus of the Popular Committees, a diverse pro-Assad movement that ran checkpoints, reported on dissidents, and attacked demonstrations in support of the army and intelligence services. Many Popular Committee groups later evolved into armed paramilitary forces and became part of state-sponsored umbrella organizations such as the National Defense Forces or the Baath Battalions. This was what saved Assad when his regime stumbled in 2011: his ability to reach beyond the limits of a purely sectarian strategy and to weaponize five decades of social control.

Five years later, Assad has spent much of this valuable human capital, and the war has deprived him of the physical security, resources, and legitimacy needed to reproduce his mechanisms for local control. As Syria’s Sunni insurgency tore through the countryside, these laboriously cultivated local networks—sometimes involving two or three generations from the same family—were shredded by the sudden loss of security control, the political and sectarian polarization, the collapsing economy, and rebel violence. The destruction of decades-old patronage networks has brutally and perhaps permanently undercut the central government’s ability to rule peripheral regions.

The Case of Idlib

The city of Idlib is an instructive example. Before 2011, it was one of the backwaters of Syrian politics, as the central town in a poor, rural, and conservative Sunni Arab governorate. For reasons of historical coincidence, Idlib’s major families had particularly fraught ties to the regime in Damascus, never having been well represented in the military–rural coalition that brought the Baath Party to power in Syria in the 1960s. The region stood in stark contrast to certain other peripheral Sunni-majority areas, such as Deraa and Deir al-Zor, which had provided large numbers of officers and politicians for the successive Baathist regimes (though their disenchantment with Damascus grew from the 1990s onwards). Idlib consequently received very little attention from Damascus, except during the unrest of the early 1980s, when then-president Hafez al-Assad dispatched the Syrian army to root out Islamist rebels from its hinterland, often with great brutality.

Some Idlibis rose to positions of influence in the liberalizing economy of the 2000s, but often found themselves unable to compete with better-connected networks composed of Alawite families or scions of the Damascene merchant bourgeoisie, which thrived under the rule of the younger Assad. The media mogul Ghassan al-Abboud is a well-known example: he was a rising star in Syrian business until, in the 2000s, he fell afoul of one of Bashar al-Assad’s cousins and was undermined by bureaucratic interference. From exile, he has since redirected his Dubai-based satellite network, Orient TV, to become a pro-opposition propaganda station. Another Idlibi, Ayman Asfari, would become tremendously wealthy as an oil magnate, but only after basing himself in the United Kingdom. He, too, now supports opposition causes.

The Pro-Assad Militias in Idlib

In Idlib, like elsewhere in the Syrian countryside, local politics were dominated by the security apparatus and the Baath Party. The main intelligence services, including the Military Intelligence Department, State Security, and the Political Security Department, had regional branch offices scattered across the city. These offices, in turn, relied on a network of party members, local informers, regime-friendly families, businessmen in need of government permits, and municipal employees to keep them informed about the city’s affairs and to influence its politics. Units of the regular army and air force were stationed in bases in the surrounding countryside, with some facilities inside Idlib, but they did not play a major role in policing or ruling the city.

When the protests began in 2011, early demonstrations in Idlib were struck down by police. Soon, the security agencies began to rely on Popular Committees to bolster their numbers and avoid putting their own officers in harm’s way. The committees were organized by pro-Assad figures, some of them eager to prove their loyalty and others simply responding to orders or financial inducements. Typically irregular and neighborhood-based, the committees erected checkpoints and patrolled neighborhoods, and would be called in to counter-demonstrate and attack pro-opposition manifestations with clubs and batons on Fridays. The opposition referred to the committees as “Shabbiha,” a derogatory term with complicated origins.

This arrangement sufficed, from the government’s perspective, until the protests took a militant turn during the summer of 2011. Armed guerrilla activity in the Idlib region began to grow rapidly from June onward. When Assad’s grip on the city began to falter more seriously in early 2012, the army was called in to clamp down on rebel activity. After the army cleared Idlib City and stationed troops there in March 2012, the provincial capital itself remained fairly calm. Yet, the uprising grew steadily across the surrounding region, thanks to supplies coming in across the Turkish border. Rebels seized the main Syria-Turkey border crossing at Bab al-Hawa in July 2012, which further facilitated the growth of the insurgency. Increasingly drained by deaths and defections, the Syrian army had little time to police Idlib City and began to farm out security functions to battle-tested local clients.

In the Syrian opposition narrative, which was uncritically adopted by many major Western media organizations in 2011, the “Shabbiha” were portrayed as criminal gangs of Alawites. Certainly, minorities did play an outsized role in many such groups, particularly in religiously mixed areas, but the exact composition of the groups varied according to local demographics. In the Sunni-dominated Qusayr area near the Lebanese border, for example, the security agencies relied on certain Greek Orthodox Christian families; in Kurdish-majority Qamishli, on Syriac Christians and members of the Sunni Arab Tai tribe; in the large city of Aleppo, on certain Sunni Arab clans from the suburbs and the surrounding countryside, as well as on Palestinians; and in Sunni-majority Homs City, primarily on Alawites.

In the case of Idlib, both the city and its hinterland are overwhelmingly Sunni Arab and marked by conservative religious values as well as strong family, clan, and village identities. As with so many other parts of what is today rebel-held Syria, it was a region where the insurgency naturally thrived, and where the government would be forced to rely on allies from within a largely pro-opposition population in order to maintain control.

To be sure, non-Sunni minorities do exist in the Idlib region. The provincial capital had a small Christian population, which was generally on good terms with the government. In addition, the nearby villages of Fouaa and Kefraya are populated by Shia Muslims and, further north, there is a small Druze enclave around Qalb Louza. That these heterodox Shia minorities preferred the Assad government to the Sunni rebellion is unsurprising, given that the dominant rebel groups in Idlib are Islamists who view the Druze and Shia faiths as an anti-Islamic apostasy meriting death, or, at best, a form of heresy that should be politically suppressed. The Druze villages around Qalb Louza have been subject to a campaign of forcible conversions and destruction of temples since they fell to the rebellion, while the Shia of Fouaa and Kefraya escaped this fate only by transforming their villages into heavily armed militia bastions, surrounded by hostile Sunni towns on all sides. (They have since become part of a complicated ceasefire arrangement.)

However, the Shia militias never seem to have been part of the regime’s security structure inside Idlib City, and Christian families do not appear to have played an important role there, either (though they do seem to have been fairly prominent in business and in the civil administration). Instead, the government relied on local contacts in the city’s majority Sunni Arab population to set up Popular Committees, run networks of informers, suppress demonstrations, and chase down suspected rebel hideouts and arms caches. In return, the Popular Committee commanders were paid, armed, trained, and given free rein to conduct their own business. This appears to have involved a great deal of lawless brutality, corruption, and score-settling, but their intelligence agency minders did not seem to mind—and in any event, they had no one else to turn to.

According to interviews with pro-opposition activists from Idlib, as well as material gathered from rebel and government propaganda and on social media, a small handful of pro-Assad militia networks emerged from 2012 onward. All of them were led by longstanding regime allies, and all of them were local Idlibi Sunnis, cut from the same cloth as the rebels themselves. The three central figures were:

- Khaled Ghazzal, a Baathist businessman with longstanding ties to the Syrian intelligence services. Ghazzal is said to have worked with the regime in the 1980s to identify and liquidate Muslim Brotherhood sympathizers during the 1979–82 Islamist insurgency. Although he has long resided abroad, he responded to the 2011 protests by raising money to pay Popular Committees consisting of his relatives, Baathists, and other residents of Idlib. As the war dragged on, his son Mohammed (also known as Abu Said) was put in charge of what later evolved into the Special Assignments Group, a paramilitary unit working alongside the army. Other important figures in the Ghazzal network reportedly included Mohannad Adib Qubeisho and Jamil Asfari, who went by the name of “Julian” and hailed from the same family as the Syrian-British multi-millionaire Ayman Asfari.

- Jamal Harmoush, a relative of Lieutenant Colonel Hussein Harmoush, who was one of the first officers to defect from the Syrian army. In 2012 or 2013, Harmoush’s Popular Committee faction seems to have been adopted into the National Defense Forces, an Iranian-backed umbrella body for militias that is connected to a central command in Damascus. In practice, of course, it remained an essentially local group.

- Jamal Suleiman, also known as Abu Salim, ran a vigilante group given Popular Committee status by the security agencies in 2011. Some reports claim that he was in prison before the war, but had been released in a deal with the government. As the war progressed, this growing force was provided with heavier arms and took on a more conventional military role in policing the city and its outskirts. Suleiman became a particular bête noire for the opposition after a video clip found its way online in 2013. In the clip, Suleiman and his men are seen interrogating a local family suspected of being rebel supporters. The visibly terrified couple is verbally and physically abused in front of their children, the woman is forced to remove her hijab, and both have their hair forcibly cut with a pair of scissors.

Spring 2015: The Rebels Take Idlib

In spring 2015, the game changed in Idlib. After months of warfare across the governorate, the two most powerful rebel factions of the region—al-Qaeda’s Nusra Front and its Salafi ally, Ahrar al-Sham—joined forces. Together with a handful of smaller factions, they created an alliance known as Jaish al-Fath, or the Army of Conquest. A surge of more-than-usually coordinated foreign support across the Turkish border further facilitated rebel advances, and a multi-pronged assault on Idlib involving thousands of fighters began in March 2015.

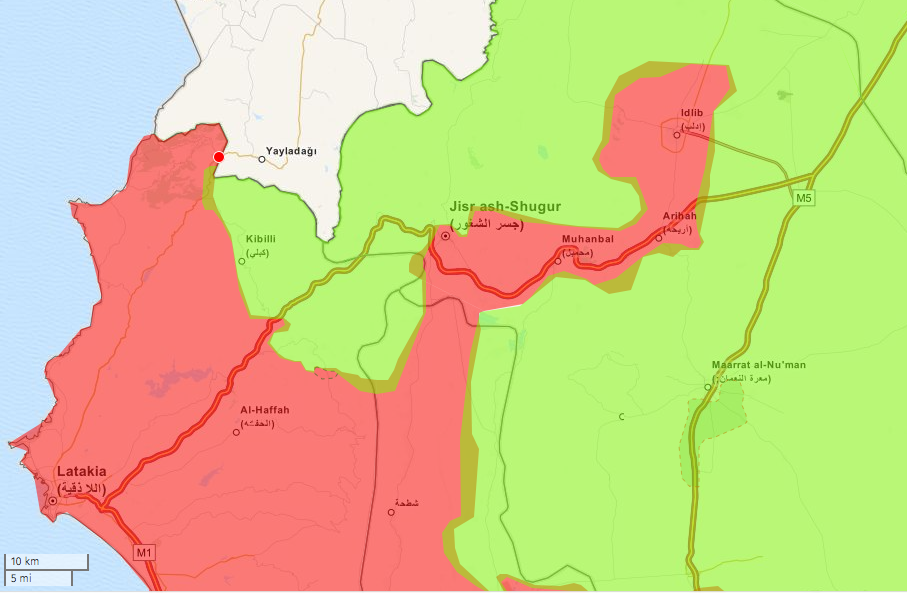

The army quickly decided to cut its losses, retreating to more defensible positions south of the city in Mastouma and a military base known as the Brick Camp. From there, Assad’s forces put up a stiff fight, although both locations were later captured. The rebels continued on, rolling up army supply lines and eliminating a pocket of government-held territory around Idlib which Assad had fought hard to keep for four years. Through Ariha, they pressed on toward the remaining army positions south of Jisr al-Shughour, which was captured within two months. It was a serious defeat for Assad, adding pressure to core regime areas in Latakia and Hama, and it seems to have been a major reason for the Russian-Iranian escalation that autumn.

Idlib City itself fell almost immediately when the army withdrew, with rebel forces pouring into the city on March 28. Much of the provincial administration had already been evacuated to Jisr al-Shughour, indicating that the regime may have been resigned to the prospect of losing Idlib once it saw Jaish al-Fath gather its troops in the surrounding villages. Most of the security apparatus apparently moved along with the civil administration or retreated with the army. This left the Popular Committees rudderless. Without their intelligence handlers to instill discipline, or the Syrian Arab Army to provide heavy firepower and protection, the web of local militias, informants, and enforcers crumbled. Many of the city’s Popular Committee chiefs seem to have fled along with their paymasters, but others were left behind, unwilling or unable to escape while there was still time.

The Purge of Idlib

Once Jaish al-Fath had secured control of Idlib in March 2015, its leaders set up sharia courts to handle judicial affairs in accordance with a conservative interpretation of Sunni Islamic law, govern the city, and manage the sometimes tense relations between the major Islamist groups. Indeed, many rebels seem to have tried to act pragmatically to preserve local institutions and stabilize the city. But in the immediate aftermath of the army withdrawal, there was a wave of looting and internal violence, including lynchings of suspected regime collaborators. Many Jaish al-Fath elements seem to have participated in the violence, though certain groups went further than others. A jihadi faction known as Jund al-Aqsa has been portrayed as leading the charge.

Much of the violence was aimed at known members of the Popular Committees, who were hated both by the rebels and by much of the city’s population, since they were seen to represent the worst abuses of the regime. Some pro-Assad fighters reportedly tried to escape Idlib dressed as women wearing the niqab, but the plan failed. Other fighters seem to have been caught as rebels searched the city, and either killed or handed to sharia tribunals for trial. There were even cases, according to an opposition supporter from the region interviewed by the author soon after the city’s fall, of Idlib-born rebels publicly executing their own pro-Assad relatives in order to clear their name and restore family honor. “They’re getting smarter, though,” the activist said with a sad smile, “because they didn’t film it this time.” Indeed, very little photographic evidence of the revenge killings spread on social media after Idlib’s fall. Among the exceptions: a picture of cheering rebels dangling what was said to be the severed head of Jamal Suleiman, perhaps Idlib’s most hated Popular Committee commander.

After the initial violence, the rebels sought to establish themselves as the new rulers of the city, which necessitated a purge of disloyal elements. Civil servants and others not directly tied to government repression were mostly left unharmed, though many fled anyway, whether because they preferred Assad to Jaish al-Fath, or simply to escape the fighting and, later, aerial bombardment by the Syrian Arab Air Force. This initial wave of refugees seems to have included nearly all of Idlib’s Christian minority.

Institutions more closely connected to the regime mostly collapsed, such as the court system. Though Jaish al-Fath apparently placed guards outside the Justice Palace in Idlib after the city fell, to preserve records and prevent looting, most of the staff seems to have vanished. Pro-government media reported that out of sixty-five judges in the Idlib region, only fifteen managed to escape to government-controlled areas. The rest may have fled elsewhere, joined the rebel side, or withdrawn from office without repercussions, but several were reportedly kidnapped and three judges were murdered in mid-July 2015. Other rebels frowned on the killings and blamed them on Jund al-Aqsa extremists, but did not want to pursue the matter for fear of causing internal conflict.

Having broken into the local intelligence headquarters and released those prisoners who remained alive, Jaish al-Fath also set about studying the documents captured there in order to weed out intelligence agents and informers. In May 2015, the group’s ruling council issued a list of some 750 wanted Assad supporters.

The Destruction of a System

It is not inconceivable that Assad could recapture Idlib City. This spring, his forces fought their way back up the Latakia Mountain ranges, coming steadily closer to Jisr al-Shughour and the areas lost in spring and summer 2015. They have since lost some ground, but with strong Russian-Iranian support they could very likely press further.

However, the uprooting of pro-regime networks in Idlib in 2015 will make the city—and the countryside that is administratively attached to it—very difficult to secure and stabilize. The men who led the militias in Idlib were all trusted regime supporters of many years, but they are now dead or scattered across Syria. With the regime’s pre-2011 client networks destroyed, the Popular Committees broken up, the Baath Party apparatus gone, the judiciary crushed, administrative records confiscated or burned, intelligence secrets revealed, institutional memory lost, and thousands of loyalist cadres on the run, the original basis of Assad’s rule in Idlib has essentially ceased to exist.

Even if Assad could muster the forces necessary to retake Idlib City, his Damascus government now lacks the administrative and repressive props that it relied on during nearly five decades of Baath Party rule and the first four years of civil war.

Even if Assad could muster the forces necessary to retake Idlib City, his Damascus government now lacks the administrative and repressive props that it relied on during nearly five decades of Baath Party rule and the first four years of civil war. After more than a year of Sunni Islamist control, who would the army hand power to? Where are the trusted supporters that can re-staff and restore the bureaucracy, Baath Party organs, and municipal functions on which government control in Idlib depended? Who would monitor the population, now that the security offices have been ransacked and the informers revealed? Who would step forth to be the new Jamal Suleiman?

The Cost of Restoration

Of course, institutions and organizations can be rebuilt and new supporters can be recruited. There is no shortage in Syria of people who would work for money, power, or merely for protection. Administrators, policemen, and bureaucrats can be trained. Some local cadres will switch sides for a second time, and a few stalwart loyalists have presumably remained in hiding in Idlib after the rebel conquest. Displaced pro-regime Idlibis could return from other parts of Syria or perhaps even from abroad.

And yet, even under the best of circumstances—which are not known to prevail in Syria—this would be a costly and time-consuming task. In the interim, the army and security services would have to handle local policing and administration, despite their already crippling shortage of manpower and money.

In fact, Idlib is emblematic of the type of rural, conservative, Sunni Arab regions that have been the engine of the uprising against Bashar al-Assad.

In a solidly pro-Assad region such as the Alawite countryside of Latakia, Homs, or Hama, the destruction of old client networks would not be such an insurmountable obstacle. Most of the local population warmly supports the army. Rebels would have few places to hide, while government and security forces would find it easy to recruit loyalists. But those are not the regions that Assad has been losing. In fact, Idlib is emblematic of the type of rural, conservative, Sunni Arab regions that have been the engine of the uprising against Bashar al-Assad. In these areas, the population is largely hostile to the army and the rebellion has local roots that are, very often, much stronger than those of the government.

In places like Idlib, it was not just the buildings, the statues, and the Baath Party murals that were targeted for destruction when Assad’s army retreated. It was also the people, the patronage networks, and the personal relationships that collectively formed the basis of Assad’s rule. Accumulated decades of social control and political leverage have been swept away with the cities themselves—all over Syria. What happened to the Jamal Suleimans of Idlib has also happened to the Jamal Suleimans of the Aleppo countryside, in Raqqa, Deir al-Zor, Deraa, and the Ghouta.

In all these regions, the grassroots machinery of Assad’s Syria has been smashed to pieces and will have to be rebuilt virtually from scratch if the Baathist regime, in its current and centralized form, is ever to return there. For a government so exhausted in terms of manpower, resources, support, and legitimacy, reconstructing a solid system of governance across the entirety of today’s Syria now seems virtually impossible. And perhaps most troublingly, no other actor will find it any easier.