Introduction

School has just started on a May morning, and a group of about a dozen sixth-, seventh-, and eighth-graders are gathered around as one of their classmates dunks his arm into a bucket of ice water. Kate Seidl, the school’s reading specialist and librarian, and Peter Redgrave, a middle school science teacher, supervise the process.

With curly hair and wearing a patterned skirt with dragons on it, Seidl looks a bit like Ms. Frizzle, the energetic schoolteacher from The Magic School Bus children’s book series. And much like the students in The Magic School Bus, the City Neighbors kids were initially skeptical of the crazy-sounding experiment.

Now they watch, enthralled, as their classmate squirms until he can stand the cold no longer and yanks his arm back out of the bucket. Siedl and Redgrave lead the class in recording data and observations from the experiment, part of an investigation of how body mass affects people’s perceptions of cold.

Additional students line up to take their turn. In the middle of class, the power goes out—one of the hazards of being located in an older building—but students barely notice.

This short science class is one of the daily tutoring sessions that City Neighbors Charter School calls “intensive learning periods.” For half an hour each morning, middle school students attend highly specialized small-group lessons. Intensive learning periods are one of the tools that City Neighbors uses to differentiate instruction without dividing students into leveled tracks.

Kate Seidl, teacher at City Neighbors Charter School, works on a project with one of her students

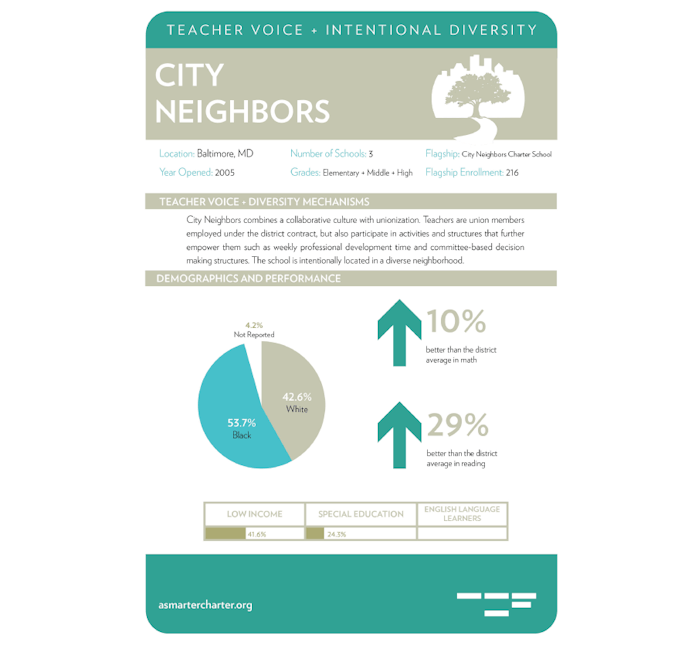

City Neighbors, a K-8 school that is part of a family of three charter schools in Baltimore, serves a diverse population of students: about 54 percent of its students are black and 43 percent are white. Forty-two percent qualify for free or reduced lunches, and 24 percent qualify for special education.

Mixed-income schools can draw criticism from two directions with respect to how well the school community and individual classrooms are integrated.

Separating students into tracked classes—divisions that too often mirror socioeconomic status—means that low- and middle-income students miss out on the peer interactions and access to broader social networks that diversity can offer.

But some research suggests that maintaining heterogeneous classes can negatively affect the academic progress of higher achievers.

City Neighbors does not track students. But that does not appear to have affected student performance. Students at City Neighbors scored 10 percent higher in math than their peers in the district and an impressive 29 percent higher than their peers in reading.

The school has won several awards for its arts and environmental curricula, and the Maryland State Department of Education recognized City Neighbors in 2009 for growth in student test scores. All this, despite having a higher-than-average number of special education students enrolled.

The successes at City Neighbors are consistent with research suggesting that it is possible, by offering all students a single challenging curriculum, to reduce the achievement gap without harming the highest performers. Indeed, Bobbi Macdonald, the school’s founder, says the school’s success in attracting a diverse student body is largely due to the school’s instructional model, which follows a progressive philosophy that emphasizes project learning, the arts, and student empowerment.

So how is City Neighbors managing this rare feat supporting lower-achieving students without hurting the higher-achievers?

How Teacher Voice Leads to Innovation

Monica O’Gara, one of the founding teachers at City Neighbors, leads her first-grade class of twenty-two students more as a guide than as a boss. Preparing her students for work time on a Thursday in late May 2013, O’Gara explained one by one where each student would work and what that student would be doing.

Monica O’Gara, one of City Neighbors’ founding teachers, leads students in a classroom exercise

Despite the rapid approach of summer vacation, students listened with rapt attention as O’Gara gave many different instructions, each based on how best to support a student or group of students. O’Gara checked in with students to see how far along they were into various projects—have you finished the drawing?—and to find out in which ways they would prefer to work—at an easel or on the floor? Once she finished with all of the instructions, students moved to their various stations efficiently and began their independent or group work.

The relationship between teachers at City Neighbors and Mike Chalupa—the school’s principal—has some things in common with the way that O’Gara manages her classroom.

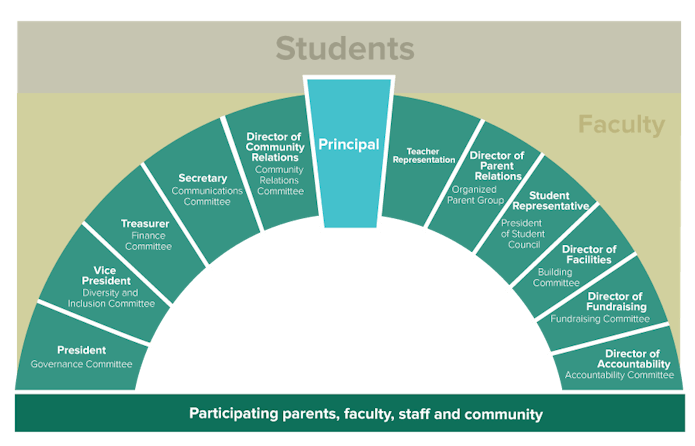

At City Neighbors, Chalupa serves as the keystone in what the school has dubbed the Governance Arch, imagined as a stone arch in which each block is a member of the school’s governing board.

The principal holds together the arch of board members that include a teacher representative and a student from the school, both full voting members of the board. But the primary role of the principal and the full arch is to support teachers, rather than supervise them, just as the teachers in turn support students.

Teachers at City Neighbors rave about the collaborative culture at their school.

Biz Manning, a special education teacher, “felt fettered” at her previous school but feels empowered at City Neighbors: “I matter here. I can teach how I want to teach, and I have a really supportive administration.”

Teachers at City Neighbors are drawn into school decisions at every level; as fourth-grade teacher Joan Jones explained, the school looks to hire teachers “that want to be involved in more than just the classroom and teaching.”

Part of this success is due to Chalupa’s leadership style.

City Neighbors principal Mike Chalupa leads a collaborative exercise

Teachers say that Chalupa respects teachers’ knowledge and communicates well. All the teachers we talked to mentioned his effective encouragement of collaboration. But established collaborative governance structures at City Neighbors help ensure teacher voice in more permanent ways that should withstand a change in administration.

“We have a culture and a process and protocol about how decisions are made,” Macdonald, the school’s founder and executive director, explained. “They’re made collaboratively, and it’s a distributed leadership model.”

The school also encourages collaboration through professional development. Every Wednesday, students have a half-day of school, and teachers use the remainder of the day to collaborate with one another and the principal.

For instance, when Tracy Pendred, a third-grade teacher, wanted to know more about her students’ experiences in previous grades, the faculty responded by creating K-3 intervention meetings to discuss students across grades. Teachers can get to know students and their individual needs before the student ever enters a class.

Macdonald stressed that “it’s inherent in the design of our school that the teachers should have a way of being around the table passionately arguing about the curriculum and looking at student work together.” Wednesday afternoon meetings help give teachers the forum for these discussions.

Meanwhile, perhaps the biggest testament to teacher empowerment at City Neighbors is the consistently positive feedback that teachers give about working at the school. The glowing endorsements we heard from teachers were echoed by data from the annual TELL (Teaching, Empowering, Leading, and Learning) Maryland survey for 2013. City Neighbors teachers provided dramatically higher ratings of their school’s climate, leadership, and structures than their counterparts in the district: 100 percent of City Neighbors teachers agreed that their school has “an atmosphere of trust and mutual respect,” compared to 69.9 percent of teachers across the district.

Intensive Learning Periods

City Neighbors combats the tension between mixed classrooms and enrichment for its strongest students through an innovative program the school calls “intensive learning periods.”

This half-hour block provides an opportunity for extra support or enrichment in different subjects, allowing teachers to meet different students’ needs while still teaching most of the academic time in mixed-ability classrooms. For example, some students may spend their intensive period receiving extra writing support while others attend an enrichment intensive period building robots.

Intensive learning periods have several features designed to create effective support and enrichment without losing the benefits of heterogeneous classrooms.

First, groupings are flexible. Over the course of a year, students take up to three different intensive classes with three different groups of peers, giving teachers multiple opportunities to adjust placements based on individual needs.

Seidl said that City Neighbors designed this unique schedule “because we know we have to be as responsive as possible.” She said they see middle school as a pivotal time for intervening to support and challenge students: “This is the place to catch kids.”

Second, the chosen topics allow teachers to group students by strengths or affinities and areas for growth at the same time. The science class investigating body mass index and perceptions of cold was part of an intensive period on science writing that grouped students who struggle with nonfiction writing but who have shown an interest in science. It is not the case that all intensive classes are strictly enrichment or strictly support, nor do all the high-achieving students end up in one set of intensive periods and the low-achieving students in another.

Third, the intensive period is focused but short. This is an all-hands-on-deck operation; all middle school staff members pitch in during intensive time to ensure low student-teacher ratios. As a result, a lot of targeted instruction is fit into thirty minutes, leaving most of the day available for students to attend mixed-ability classes.

All-hands-on-deck programs may be de rigueur at private prep schools, but such things are rare in public schools. How did City Neighbors get all its teachers on board for this sort of intensive experiment?

Teacher Voice + Diversity = Democracy

It is no coincidence that City Neighbors’ success in empowering teachers has translated to success in educating a diverse student body. Indeed, teacher voice and student diversity are driven by a common appreciation for diverse voices.

Bobbi Macdonald, the school’s founder, explains that “democracy and public education” are at the heart of the founding philosophy at City Neighbors. That founding philosophy was heavily influenced by-among others-John Dewey, the great American philosopher and educator.

John Dewey, American philosopher and educator

Dewey famously argued that education and democracy were inseparable, because genuine education required freedom of thought and true democracy required an educated populace of critical thinkers who could fairly evaluate candidates for public office.

Macdonald’s Dewey-inspired vision for charter schools is a direct intellectual descendant of Albert Shanker, the long-time president of the American Federation of Teachers who first proposed charter schools in 1988.

Democracy was central to Shanker’s overall vision of education. Shanker absorbed Dewey’s views on democracy and education as a graduate student in philosophy at Columbia University, where he was taught by Dewey’s students. Shanker was a Social Democrat, a group for whom the philosopher Sidney Hook said that “democracy is not merely a political concept, but a moral one.” Democracy was Shanker’s touchstone, just as the marketplace is for conservatives.

Albert Shanker, president of the American Federation of Teachers and early champion of the charter school movement

So when Shanker first proposed these new “charter schools,” he imagined a more purely democratic version of traditional public schools. If public schools did not in practice always live up to 19th-century educator Horace Mann’s ideal as institutions that educated the children of the rich and poor and different races and religions side by side, integrated charter schools could go beyond neighborhood segregation to realize the concept more fully.

Likewise, if unionized schools did not always tap into the knowledge, ideas, and expertise of teachers, charter schools might do so by allowing small groups of teachers to try new things. Shanker’s fight for teacher voice in charter schools was connected to the idea that in democratic institutions, individuals’ opinions and expertise should be valued.

As institutions that empowered teachers and integrated students, charters could do in practice what even the regular public schools often failed to accomplish: create genuinely democratic environments.

City Neighbors Charter School in Baltimore is one place where Shanker’s democratic vision is alive and thriving.

This pluralist approach unites City Neighbors’ focus on empowering teachers and integrating students: the school community values having different strengths, talents, and voices represented among both teachers and students. Furthermore, giving teachers voice in school decisions empowers them as advocates for the needs of diverse learners. “There is a very strong teacher voice for the best interest of the kids,” special education teacher Biz Manning explained.

Students educated in diverse groups, led by teachers and administrators who themselves model democracy, have the best chance of succeeding in an evolving twenty-first-century society and economy.

The late Manning Marable, a historian, social critic, and fighter for racial and economic justice, sums this perspective nicely:

I believe that real academic excellence can only exist in a democracy within the framework of multicultural diversity. Indeed, our public school systems, despite their serious problems, represent one of the most important institutional safeguards for defending the principles of democracy and equality under the law…Public education alone has the potential capacity for building pluralistic communities and creating a lively civic culture that promotes the fullest possible engagement and participation of all members of society. In this sense, the public school is a true laboratory for democracy.

At City Neighbors Charter School, where teachers are important voices in school leadership and students represent the full racial and socioeconomic diversity of their community, the democratic school environment is thriving.