Introduction

Earlier this year, Harvard University public policy professor Robert D. Putnam published the blockbuster social policy book of 2015: Our Kids: The American Dream in Crisis.1 A giant among intellectuals, Putnam is best known for his groundbreaking 2000 volume Bowling Alone, which documented a troubling decline in civic engagement and sounded the alarm about America’s declining social capital. Our Kids looks at another troubling aspect of our fragmenting society—America’s growing economic divide—and marshals considerable evidence to suggest that social mobility in America seems “poised to plunge in the years ahead.”2

The book has received an extraordinary amount of attention, including from President Barack Obama. It is not every day that a sitting United States president partakes in a panel discussion with an author, but when Our Kids was published, Obama joined Putnam and others at Georgetown University to discuss the country’s burgeoning economic divisions. Drawing upon Putnam’s themes, President Obama employed strikingly blunt language to suggest that “what used to be racial segregation now mirrors itself in class segregation.”3

As I noted in my review of Our Kids in the Washington Monthly, Putnam does a superb job of outlining the problems facing the United States, but he spends less than one-tenth of the book discussing public policy responses.4 Recognizing that Our Kids was largely diagnostic in nature, Putnam has since created a series of working groups to devise policy proposals.

As a supplement to those efforts, this report recaps Putnam’s findings about the changing nature of inequality over the last sixty years and seeks to offer workable policy ideas that logically flow from Putnam’s analysis in four areas: housing, K–12 schooling, higher education, and the workplace. A premium has been placed on polices that are grounded in solid research and are politically attractive to a wide range of people.

In brief, to help counteract the problems stemming from nationwide economic segregation, this report suggests that we need:

- a Fair Housing Act for working-class people,

- a Brown v. Board of Education policy for low-income pupils,

- an affirmative action program in higher education for economically disadvantaged students, and

- an amendment to the Civil Rights Act to prohibit discrimination against workers engaged in labor organizing.

Indeed, we need a new civil rights movement for poor and working-class people that runs parallel to the ongoing fight for racial equality.

Putnam’s Diagnosis

One of the key findings of Our Kids is that, while America has made progress on combating racial and gender-based inequality over the past several decades, economic inequalities are growing.

On the surface, this thesis might seem obtuse given the headlines in recent months—the brutal slaying of black churchgoers by a white supremacist in Charleston, South Carolina, and the string of deaths of unarmed black men at the hands of police in Ferguson, Missouri, Baltimore, Maryland, New York City, and elsewhere. But Putnam is quick to acknowledge that race and gender discrimination remain serious problems.

It would be nonsense to suggest we have become a “post-racial” society. Movements like Black Lives Matter, for example, have brilliantly drawn attention to long-standing problems of police brutality against African Americans. Putnam recognizes that the nation needs a continued and robust civil rights movement that targets race-specific problems such as those in our criminal justice system, in education, in employment, and in housing.

Putnam’s research, however, also shows a parallel set of worsening problems in that the threads of our social fabric—and the benefits that result from being an American—are becoming increasingly divided by class.

The need to address racial and economic equality is not new—in fact, in 1968, Martin Luther King Jr. advocated a Poor People’s Campaign to supplement civil rights efforts for black people—but the rationale for creating a movement to address class inequality has only grown in subsequent decades.

If we examine issues of class, race, and gender—the intersection of which frequently determines the winners and losers in our society—we see over the past half century considerable (if insufficient) progress for minorities and women, but also movement in the wrong direction for poor and working-class Americans. Putnam writes, “the power of race, class and gender to shape life chances in America has been substantially reconfigured.”5

Consider, for example, the issue of marriage across racial and class lines. Whereas interracial marriage was illegal in many states a mere fifty years ago, today it is increasingly common. By contrast, while marriage across class lines was increasingly accepted in the first half of the twentieth century, Putnam notes, subsequently, “that trend reversed itself” as educated people became less likely than in the past to marry those with less education.6

Likewise, social differences that were long thought to track primarily by race now increasingly follow class lines. For example, Daniel Patrick Moynihan famously highlighted the issue of racial differences in family structure in his 1965 report, The Negro Family. But as Putnam writes, while “in the 1970s, the two-tiered family structure was closely correlated with race . . . since that time it has become increasingly associated with parents’ social class more than race.” Furthermore, “college-educated blacks are looking more like college-educated whites, and less-educated whites are looking more like less-educated blacks.”7 For example, today, less than 10 percent of children up to 7 years of age with a college-educated parent live in a single-parent household, compared with more than 65 percent of those children whose parent has a high school degree or less.8

Putnam’s narrative of the growing salience of class inequality is illustrated by the story of his hometown of Port Clinton, Ohio, where he graduated from high school in 1959. In those days, race and gender had enormous influence; bright women typically dropped out of college when they got married, and an African American classmate of Putnam’s once had a cross erected in her yard when her family sought to move into a white neighborhood.9

Meanwhile, low economic status back then was less of an impediment than it is today. In the 1950s, within Putnam’s predominantly white town, children of different classes “mixed unselfconsciously in schools and neighborhoods” and most came from two-parent households.10 It was an era of “strong unions” and social class “was not a major constraint on opportunity.”11

Putnam writes: “My hometown was, in the 1950s, a passable embodiment of the American Dream, a place that offered decent opportunity for all the kids in town, whatever their background.” Today, however, “kids from the wrong side of the tracks that bisect the town can barely imagine the future that waits the kids from the right side of the tracks.”12

The growing class divide that Putnam traces has a huge impact in four major areas of public policy: housing, K–12 schooling, higher education, and the workplace.

Housing and Communities

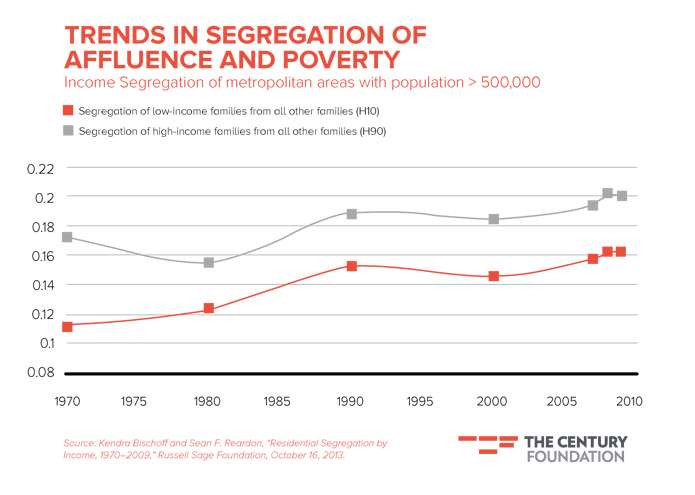

America’s residential areas have long been segregated by race, and continue to be so today. But a new class-based segregation is emerging. Income segregation by neighborhood, Putnam says, “was significantly higher in 2010 than it was in 1970”13 (See Figure 1).

Figure 1

He suggests, “while race-based segregation has been slowly declining,” we have seen the rise of “a kind of incipient class apartheid.”14 This matters because living in a poor neighborhood is associated with reduced educational opportunities, diminished health outcomes, and lower levels of civic engagement.”15 There is also more communal parenting in wealthier areas, and higher levels of social trust.16

K-12 Schooling

Schooling historically has been unequally distributed by race in America, but Putnam finds that, increasingly, the key divide is class. Rising residential segregation by class “has been translated into de facto class-based school segregation.”17 Taken together with rising poverty rates, the nonprofit group EdBuild reports that between 2006 and 2013, there was a 260 percent increase in the number of students living in school districts with concentrated poverty.18

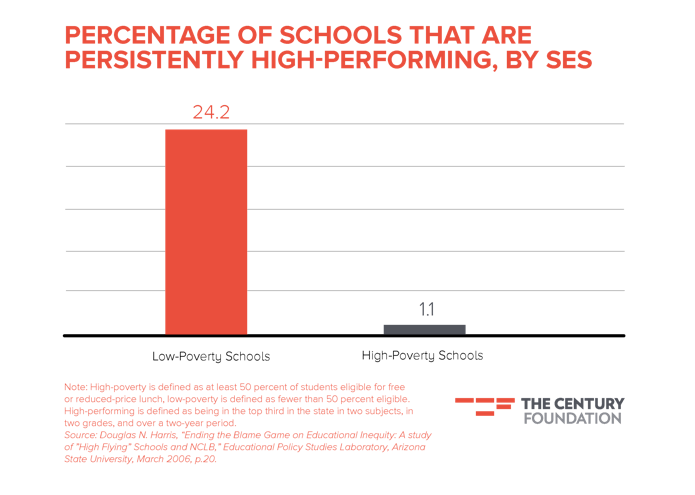

Concentrations of school poverty are troublesome, Putnam writes, because extensive evidence suggests, “Whom you go to school with matters a lot.”19 One study Putnam cites finds that, after controlling for family and academic background and school inputs, students who attend a high school with classmates from a high socioeconomic status have a 68 percent higher probability of enrolling in a four-year college than a student who attends a school where classmates have a low socioeconomic status.20 The press likes to write about high-poverty schools that beat the odds, but in fact, middle-class schools are twenty-two times as likely to be high-performing as high-poverty schools. (See Figure 2).

Figure 2

Middle-class schools are more successful, in part, because middle-class students face fewer obstacles to academic success than low-income students, but concentrations of poverty are also associated with lower outcomes. On the 2011 National Assessment of Educational Progress in fourth grade mathematics, low-income students in high-poverty schools are as much as two years behind low-income students in more-affluent schools. 21 Studies that control for self-selection find a powerful effect remains. 22

Upper-middle-class schools congregate peers who plan to go to college, while high-poverty schools have four times the concentration of students with academic, attention, and behavioral problems. 23 In middle-class schools, parents can provide as much as a 17 percent boost in school budgets through private fundraising and demand three times as many AP classes as in high-poverty schools. 24 The key determinant of AP classes is “parental income, not race,” Putnam notes. After controlling for poverty, urbanism, school size, and other factors, “heavily minority schools actually offer more AP courses than mostly white schools.” 25 Finally, middle-class schools tend to draw stronger teachers who avoid the tougher working environment found in high-poverty schools.26

Coinciding with this period of rising economic school segregation has been an increase in the math and reading test score gap by income. While the achievement gap between black and white students has slowly decreased over time, Putnam notes that Stanford sociologist Sean Reardon’s landmark study from 2011 finds that the income achievement gap has grown 30–40 percent for children born in 2001 compared with those born twenty-five years earlier.27

Higher Education

In higher education, Putnam reports that racial and (especially) gender barriers have waned, as class barriers are on the rise. While women used to drop out of college in large numbers to get married, today, “women are more likely to graduate from college than men.” 28 Minority students remain underrepresented at selective colleges, but students from the bottom socioeconomic quartile are far more dramatically underrepresented. In 2006, whites were overrepresented at the most selective colleges by 15 percentage points, but the richest socioeconomic quarter of the population was overrepresented by an astounding 45 points.29 Despite considerable media attention given in the past decade to the lack of socioeconomic diversity at selective colleges, very little change has occurred, according to a 2015 report by the University of Michigan’s Michael Bastedo.30

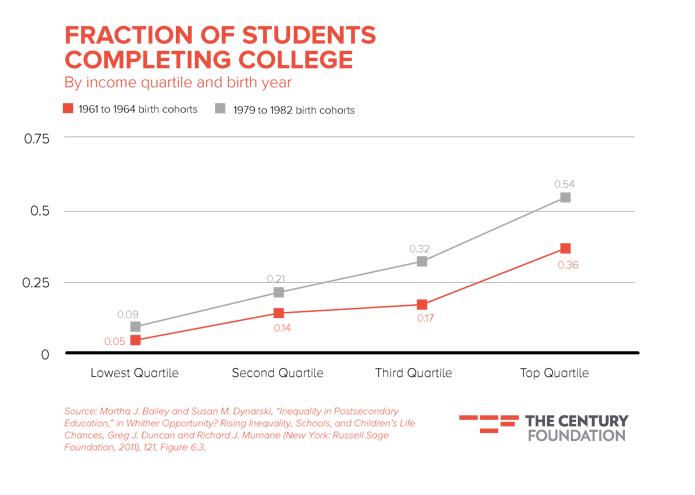

More broadly, the income gap in bachelor’s degree attainment has grown substantially. According to research by Martha J. Bailey and Susan M. Dynarski of the University of Michigan, “inequality in college outcomes by family income increased dramatically in recent decades.”31 Children of wealthy families have increased their college graduation rates by 18 percentage points, while those from poor families have increased just 4 percentage points, so that the students of wealthy families are now six times as likely to graduate (54 percent versus 9 percent) (See Figure 3).

Figure 3

The Workplace

In analyzing the changes in America since the 1950s, Putnam mentions—but mostly in passing—the decline of unions in America. Putnam would have been smart to dwell on this phenomenon at greater length given its deep connection to the prospects of adults—and their children. As labor lawyer Thomas Geoghegan dryly point out, while policymakers are busy figuring out ways to remedy the negative effects of poverty-induced stress on children, “it would seem simpler to raise the parent’s wage.”32 Indeed, Putnam notes that an increase in a parent’s income by $3,000 in a child’s first years of life is associated with academic gains on the order of 20 SAT points and adult earnings that are nearly 20 percent higher.33

Employment earnings are determined in part by the prevalence of employer discrimination, and—as with other arenas Putnam studies—the last half century has seen a shift in discriminatory behavior of employers from race to class. Before the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, open and flagrant employment discrimination against African Americans was common. While racial discrimination in employment remains a problem, Putnam notes that “controlling for education, racial gaps in income are modest.”34

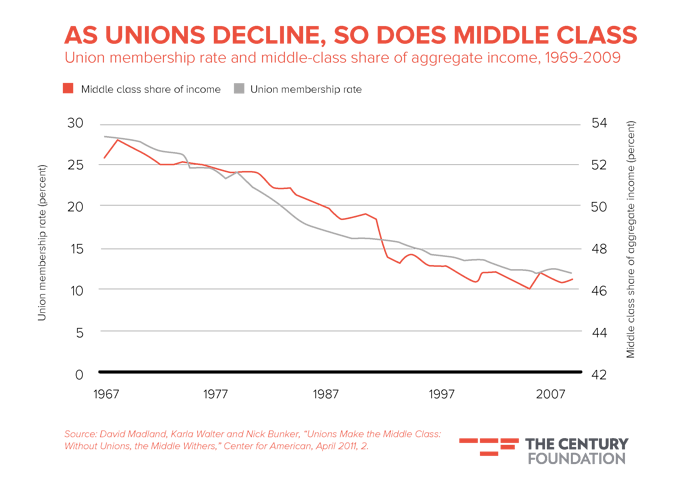

By contrast, class-based discrimination against workers trying to unionize has been on the rise, and average wage earners as a group are paying the price. In the 1950s, organized labor represented one-third of private sector workers, and America enjoyed broadly shared prosperity, as workers were able to win a fair share of productivity gains.35 Since then, as researcher David Madland at the Center for American Progress has shown, declines in organized labor neatly coincide with declines in the share of income going to the middle three-fifths of the income distribution (See Figure 4).

Figure 4

Over time, businesses began to openly discriminate against employees trying to organize a union, a practice that has essentially stopped labor organizing in its tracks. Globalization has caused unions to suffer throughout the world, but the fall of unions in the United States has been much steeper than in other countries also subject to the forces of globalization. Routine employer discrimination against union organizing has caused Freedom House to rate the United States as far less free on labor rights than forty-one other countries.36

Policy Strategies

What is to be done? Putnam, who in Our Kids does an exhaustive and masterful job of analyzing the forces that have fueled inequality of economic opportunity, devotes less than 10 percent of his ink to solutions. Even so, he outlines a variety of good ideas, including expanding the Earned Income Tax Credit, reducing over-incarceration, broadening access to high-quality early childhood education, and boosting funding to community colleges.37 And additionally, Putnam has created a series of five working groups to come up with additional policy solutions, which should advance the debate in important ways.38

Here is one big theme to consider: conceptually, if Putnam’s central thesis is that class divisions are becoming our central source of inequality, should we not consider updating our civil rights laws to address class inequality alongside race?

Although civil rights laws were enormously controversial when passed, today, the principle of nondiscrimination regarding race (and gender) in education, housing, and employment is firmly embedded and widely embraced. Today, the civil rights movement is an enormous source of pride for many Americans, so it makes good policy and political sense to extend successful civil rights remedies to larger class inequities.

Below are ideas—drawing from an established body of Century Foundation work—for how to extend civil rights remedies in four key areas that Putnam discusses: housing segregation, school segregation, higher education, and the workforce.

Addressing Housing Segregation

The Fair Housing Act of 1968 is an important federal law that makes racial discrimination in housing illegal. The U.S. Supreme Court recently affirmed a key feature of the law that makes it possible to bring so-called “disparate impact” lawsuits against policies that have a discriminatory impact on minorities, even absent a discriminatory intent.39 And a new rule by the Obama administration’s Department of Housing and Urban Affairs to enforce a requirement that local recipients of federal housing funds “affirmatively further” fair housing makes good sense.40 Residential segregation by race remains an enormous problem, even if the trajectory is slowly headed in the right direction—integration.

Income segregation, however, is growing, and we need new tools to combat that problem directly. Below are three policy ideas to reduce stratification and de-concentrate residential poverty, an approach that has a proven track record of helping families and their children succeed.

1. A New Fair Housing Act to Outlaw Exclusionary Zoning

We need a federal Fair Housing Act (and state fair housing acts) for low-income and working-class people. Just as it is illegal to discriminate in housing based on race, it should be illegal for municipalities to employ exclusionary zoning policies (such as minimum lot sizes) that discriminate based on income.41 At the individual housing unit level, free market forces set housing prices in a way that makes some homes unaffordable to many people. But on top of that, government zoning policies discriminate based on income by rendering off-limits entire communities where it is impossible to rent an apartment or purchase a home on a small plot of land.

A Fair Housing Act for low-income families would make clear that, just as it is unacceptable for neighborhoods or individuals to discriminate based on race, it should also be unacceptable for government policies to exclude low-income and working-class families from entire neighborhoods. Such a policy would harness not only liberal arguments about equity but also conservative principles tied to liberty: the government should get out of the way and allow individuals to build at greater density levels than exclusionary zoning allows.

A federal act that eliminated exclusionary zoning would echo a longstanding legal effort to curtail exclusionary zoning policies in the state of New Jersey. In 1975, the New Jersey Supreme Court ruled in Southern Burlington County NAACP v. Mount Laurel that zoning laws that have the effect of excluding low-income families violate the New Jersey constitution. The court ruled that localities have an affirmative obligation to provide their “fair share” of moderate and low-income housing.42

Although implementation of the Mount Laurel decision has often proven difficult, thousands of low-income families who have been allowed to move to low-poverty neighborhoods as a result of the decision have benefited greatly.43 As Putnam notes, under Mount Laurel, “poor kids whose families were moved into a more affluent area achieved higher test scores and went further in school than comparable kids who were not moved.”44 The principle underlying the Mount Laurel decision should be written into federal law.

2. Expand Inclusionary Zoning Policies

Curtailing exclusionary zoning would reduce outright discrimination against low-income and working-class families, but “inclusionary zoning” policies go a step further. Under inclusionary zoning programs, a developer must set aside a portion of new housing units to be affordable for low- and moderate-income residents, receiving in exchange a “density bonus,” that allows him or her to develop a larger number of high-profit units than the area is zoned for. This benefit for developers has proven critical to the idea’s political acceptance. According to researcher David Rusk, 11 percent of Americans now live in jurisdictions with inclusionary zoning policies nationally.45

A leading example is Montgomery County, Maryland, which adopted a groundbreaking program in 1974. Under the policy 12.5 percent to 15 percent of a developers’ new housing stock must be affordable for low-income and working-class families. Between 1976 and 2010, the program produced more than 12,000 moderately priced homes, of which the housing authority has the right to purchase one-third for public housing.46

Research suggests the program has had an important positive effect on student achievement. In a 2010 Century Foundation report, Heather Schwartz compared the effects of inclusionary zoning within Montgomery County on academic outcomes of elementary school students with a parallel county strategy to help low-income students by providing compensatory spending in higher-poverty schools. (Beginning in 2000, the school district began spending about $2,000 extra per pupil in higher-poverty schools for all-day kindergarten, reduced class sizes, and investments in teacher development.)

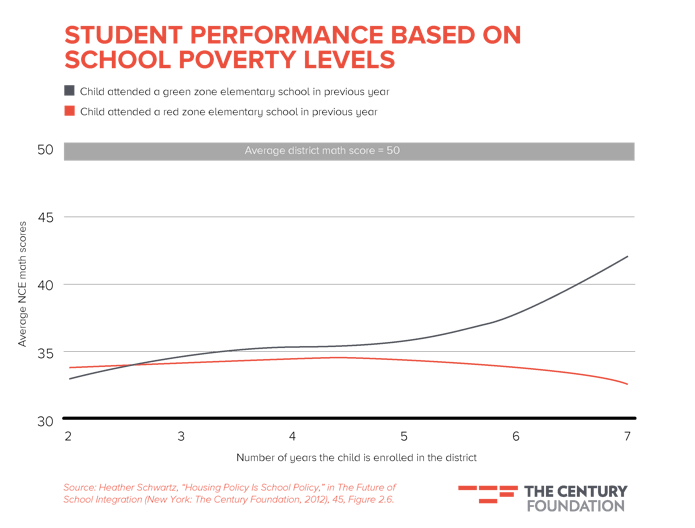

Schwartz examined 858 children randomly assigned to public housing units scattered throughout Montgomery County and enrolled in Montgomery County public elementary schools between 2001 and 2007 and asked: Who performed better—public housing students in higher poverty neighborhoods where schools have extra financial resources or students in lower poverty schools that spend less? The results are outlined in Figure 5.

Over time, low-income public housing students in low-poverty (“green zone”) schools performed at 0.4 of a standard deviation better in math than low-income public housing students in higher-poverty (“red zone”) schools with more resources. Because educational interventions typically have an effect size on the order of 0.1 of a standard deviation, the outcomes in Montgomery County are considered quite powerful. Low-income students in “green zone” schools cut their large initial math gap with middle-class students in half. The reading gap was cut by one-third. Schwartz estimates that most of the effect (two-thirds) was due to attending low-poverty schools, and some (one-third) was due to living in low-poverty neighborhoods.

Figure 5

3. Revive and Expand the Federal Moving to Opportunity Program

The federal Moving to Opportunity (MTO) program represents a third strategy to de-concentrate poverty that deserves to be expanded. The experiment, run by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development between 1994 and 1998, offered a randomly selected set of families living in high-poverty housing projects the opportunity to move to lower-poverty neighborhoods. In five major cities, 4,604 families were randomly assigned to one of three groups: those receiving a voucher to move to a census tract with a poverty rate below 10 percent, those receiving a voucher to live anywhere, and a control group that was not offered a voucher to move.47

The initial studies on outcomes for children showed very modest effects for the children of families able to move to low-poverty neighborhoods. But when researchers looked more closely, the results were not surprising because the treatment group attended schools that were not much different than the schools attended by the control group. In the treatment group, 67.5 percent of classmates were low-income compared with a control group attending schools with 73.9 percent of students receiving subsidized lunches.48

More recent research on the longer term effects of MTO has been far more favorable. In a May 2015 National Bureau of Economic Research working paper, Raj Chetty, Nathanial Hendren, and Lawrence F. Katz found that the adult outcomes of moving to a low-poverty neighborhood were significant for those who moved as children before the age of 13. The total mean income as adults for early movers was 31 percent higher than for the control group. The researchers also observed a 16 percent increase in the likelihood of attending college between the ages of 18 and 20.49

Overall, the evidence gives reason to expand MTO-type interventions in the future as a method of combating increasing economic segregation and providing opportunity for low-income children.

Addressing School Segregation

Brown v. Board of Education represented a monumental advance in American society and American education. When desegregation was actively implemented beginning around 1969, the outcomes of African Americans rose, and did not decline for whites. Scores rose fastest for black students in the South, where desegregation had its biggest bite.50

Over time, however, the U.S. Supreme Court cut back on requirements that school districts desegregate. And in 2007, the Supreme Court struck down voluntary racial integration plans in Seattle and Louisville as unconstitutional.

The good news, however, is that it remains perfectly legal to consider the socioeconomic status of families in student assignment plants. Moreover, if districts are focused on raising test scores, a long line of research suggests that it is the socioeconomic status of classmates—even more than their race—that matters.51 Of course, there are reasons to promote racial integration apart from the effect on test scores. We want schools to teach an appreciation for diversity and to foster social cohesion. So it is relevant that, given the overlap between race and class in American society, socioeconomic integration will often yield significant racial integration as well. Below are three strategies for promoting greater socioeconomic integration in schooling.

1. Socioeconomic Integration of Traditional Public Schools

Today, more than eighty school districts, educating some four million students, make conscious efforts to integrate schools by socioeconomic status.52 Unlike compulsory busing programs from the 1970s, these programs tend to rely on voluntary school choice programs and incentives such as special magnet school themes to achieve integration. Districts pursuing socioeconomic integration range from mid-size towns (such as La Crosse, Wisconsin) to major urban areas (such as Chicago, which integrates a subset of its schools) and range from the South (Raleigh and Louisville) to the North (Cambridge, Massachusetts and Champaign, Illinois). New York State, for example, recently adopted a socioeconomic integration pilot program to provide funds to struggling high-poverty schools to create attractive magnet school programs to draw a broader economic mix of students.53

Some socioeconomic integration programs involve inter-district choice between schools in the city and suburbs out of recognition that most segregation lies between districts. And districts have become increasingly sophisticated in their implementation of plans. In identifying magnet school themes or pedagogical approaches, administrators in the best programs do not guess at what will be attractive to parents but rely on sophisticated polling data. To make their schools desirable, school districts often build partnerships between particular magnet schools and well-regarded institutions (universities, museums, military facilities, sports teams, and private sector institutions).

Some urban magnet schools are sited near workplaces so as to draw in parents who would like their children to attend school near their jobs. Over time, if certain school themes or pedagogical approaches prove popular, those programs can be expanded. If, for example, schools with Montessori teaching approaches and language immersion programs are oversubscribed year in and year out, those popular programs can be franchised.

Although even voluntary school integration plans can be contentious, strong political support can come from a variety of sources. Teachers unions in La Crosse, Wisconsin and Louisville, Kentucky have been supportive of socioeconomic integration because teachers know they can do a better job when poverty is not concentrated in certain schools. Civil rights groups have joined with business groups in places like St. Louis and Raleigh to support integration because employers want employees who can get along with people of different backgrounds. Magnet schools parents and faith groups can also be strong backers of socioeconomic integration plans.

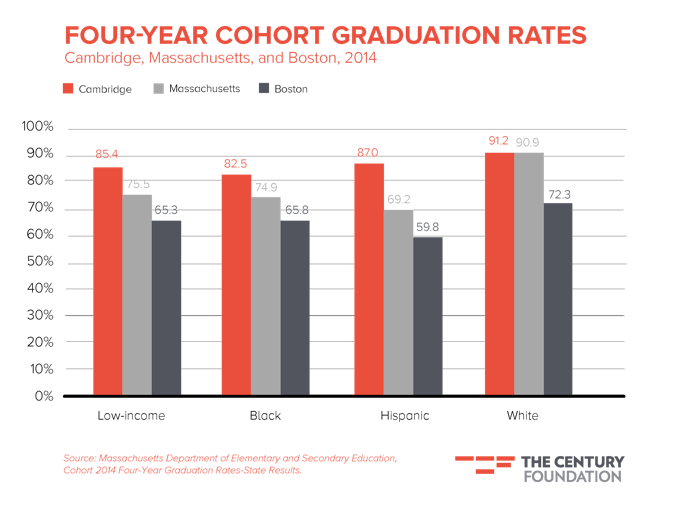

A leading example of the magnet school model is Cambridge, Massachusetts, which has adopted universal public school choice. There are no automatic neighborhood schools to which children are assigned. Instead, families choose from among a variety of magnet school themes and teaching approaches, and school officials honor those choices with the goal of making all schools within plus or minus ten percentage points of the school district average for free and reduced price lunch eligibility. First adopted for elementary schools in 2000, Cambridge’s socioeconomic integration plan is associated with impressive high school graduation rates compared with nearby Boston and the state of Massachusetts as a whole (See Figure 6).

Figure 6

2. Socioeconomic Integration of Charter Schools

The burgeoning charter school sector also represents a ripe opportunity to advance socioeconomic school integration. Although many charter schools are actually more segregated than the traditional public schools, a growing number are taking conscious efforts to integrate by socioeconomic status. That movement is consistent with the vision of early advocates of charter schools, such as American of Teachers president Albert Shanker, who argued that unionized charter schools could bring children of different neighborhoods together and all would benefit from the resulting diversity.54

In our 2014 book, A Smarter Charter, my colleague Halley Potter and I profile nine charter schools that make special efforts to be economically and racially diverse: City Neighbors, High Tech High, Morris Jeff Community School, Blackstone Valley Prep, Capital City Public Charter School, DSST Public Schools, E. L. Haynes Public Charter School, and Larchmont Charter School. Some of these schools intentionally locate in mixed-income neighborhoods, while others use lotteries based on zip code or family income to promote diversity. As we outline in the book, outcomes at all of these schools are impressive, based both on traditional indicators, such as test scores and graduation rates.

As the number of intentionally integrated charter schools has grown, a National Coalition of Diverse Charters has formed, with twenty-eight member schools and networks together operating more than one hundred charter schools across the country.

3. Socioeconomic Integration of Early Childhood

Just as socioeconomic integration of traditional public schools and charter schools benefits students, so, research suggests, does the integration of early childhood programs. Indeed, the power of peer influence in pre-K programs may be even greater, as much learning is achieved through play with classmates. With the expansion of universal pre-K programs in jurisdictions such as New York City, there are unique opportunities to promote socioeconomically integrated pre-K programs.55

As early childhood education researchers Jeanne L. Reid, Sharon Lynn Kagan, Michael Hilton, and Halley Potter outline in their 2015 report, A Better Start: Why Classroom Diversity Matters in Early Education, a small but growing number of early childhood education settings are intentionally diverse. The report highlights, for example, pre-K programs associated with Morris Jeff Charter School in New Orleans and early childhood centers connected to Hartford’s regional magnet schools.56Jeanne Reid’s research, involving almost three thousand four-year-olds in eleven states, finds that controlling for the individual socioeconomic status of student families, being in a classroom with an above-average socioeconomic status had a positive impact on achievement in three areas: receptive language, expressive language, and math learning. The effect size was comparable to children’s own socioeconomic status and instructional quality—two factors known to be very important.57

Addressing Higher Education Segregation

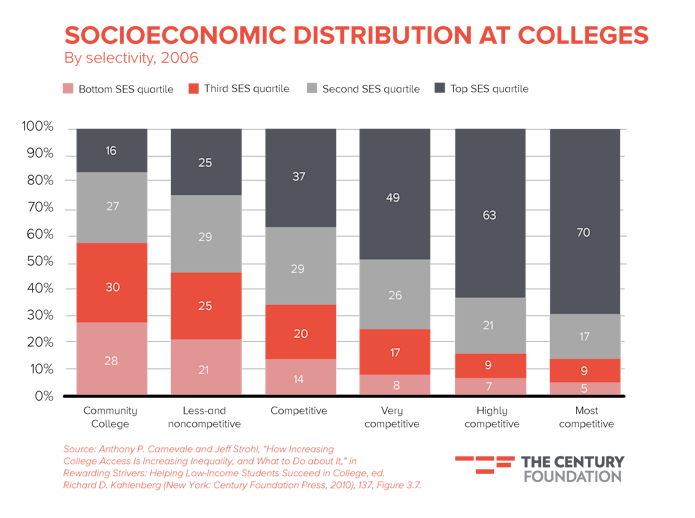

Affirmative action programs in higher education, first introduced in the 1960s, have opened the doors of selective colleges for thousands of African American and Hispanic students. But today, racial preferences are under intense legal and political attack, and they have not fully addressed issues of economic inequality. Even with affirmative action programs in place, at selective colleges, rich kids outnumber poor kids by fourteen to one.

Looking more broadly across institutions of higher education, the good news is that more low-income students are going to college than ever before, but the bad news is that socioeconomic stratification within higher education has grown, so that today, low-income students outnumber wealthier students at community colleges by two to one (See Figure 7).

Figure 7

This stratification matters because, even controlling for entering student characteristics, researchers have identified benefits to attending highly selective four-year colleges and a “penalty” associated with attending community college, defined as a reduced chance of eventually receiving a bachelor’s degree.58 We need strategies to reduce economic segregation in higher education, both by allowing more economically disadvantaged students to attend selective colleges and strengthening community colleges.

1. Class-Based Affirmative Action

As traditional race-based affirmative action programs come under increasing attack, we need new paths to diversity that emphasize economic disadvantage broadly defined.

In ten states where the use of race has been eliminated by voter initiative or other means at leading universities, several creative steps have been taken. Six states have spent money to create new partnerships with disadvantaged schools to improve the pipeline of low-income and minority students. Eight states have provided new admissions preferences to low-income and working-class students of all races. Eight states have expanded financial aid budgets to support the needs of economically disadvantaged students. In three states, individual universities have dropped legacy preferences for the generally privileged—and disproportionately white—children of alumni. In three states, colleges created policies to admit students who graduated at the top of their high school classes. And in two states, stronger programs have been created to facilitate transfer from community colleges to four-year institutions.59

Survey data finds that these types of approaches—which tend to benefit economically disadvantaged students of all races—garner far stronger political support than race-specific programs.60 The political support comports with research findings to suggest that, if we want to give a leg up to students who have overcome obstacles, socioeconomic hurdles account for an expected 399 point penalty on the SAT, compared to a penalty for African American students of 56 points.61

One prominent example of a class-based approach is Texas’s “Top 10 Percent” plan, which automatically admits students in the top tier of every high school to any public university, including the flagship, the University of Texas at Austin. In 2004, the Top 10 Percent plan, combined with socioeconomic affirmative action (but no consideration of race), produced a freshman class that was 4.5 percent African American and 16.9 percent Hispanic. These proportions were slightly higher than the 4.1 percent African American and 14.5 percent Hispanic numbers achieved using racial preferences in 1996.62

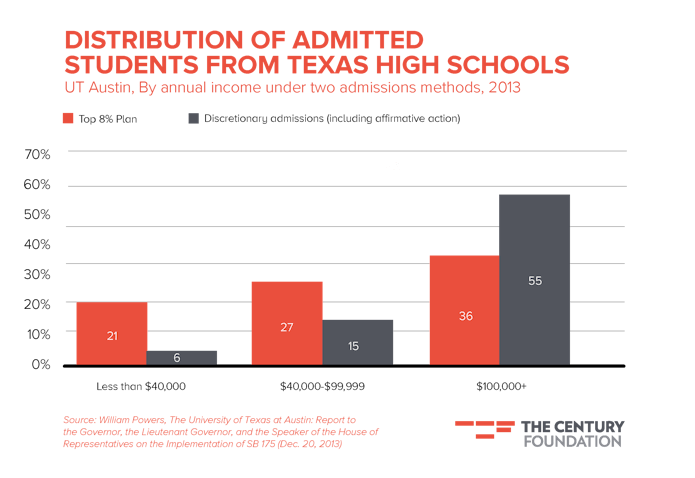

Significantly, the Texas Top 10 Percent plan also produces considerable socioeconomic diversity. Today, the University of Texas at Austin admits about three-quarters of its freshman class through the percentage plan (now limited to the top 8 percent), and one-quarter through discretionary admissions (which now includes consideration of race). As Figure 8 shows, top 8 percent enrollees are more than three times as likely as students admitted through discretionary means to come from low-income families, while discretionary enrollees are substantially more likely to be wealthy.

Research by Marta Tienda and Sunny Niu finds that students admitted though the percentage plan have fared well academically at the University of Texas at Austin.63 Efforts to curtail the program have been met with strong resistance from a remarkable coalition of conservative white rural legislators and liberal black and Hispanic urban legislators, whose respective constituencies have benefited from the plan.64 The long-run effects of the program on adult outcomes is not yet fully known, but it is encouraging to note that research by Stacy Dale and Alan Krueger finds that low-income and minority students see the greatest wage gains from attending selective colleges, perhaps because they are exposed for the first time to advantaged professional networks.65

Figure 8

Nationally, seven of ten leading universities that tried to create alternatives to racial affirmative action programs were able to sustain black and Hispanic representation. But critics note that three other universities—the University of California at Berkeley, the University of California at Los Angeles, and the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor—have been less successful than others in promoting racial diversity in the face of bans on racial preferences. But minority declines are not entirely surprising because these three schools recruit from a national pool of students and face an impossible situation. Most universities can still use racial preferences in admissions while these three schools have unilaterally disarmed in the battle to recruit talented minority students. Indeed, minority students admitted without consideration of race at Berkeley or Michigan may also get into even more prestigious universities such as Stanford or Princeton with a preference.

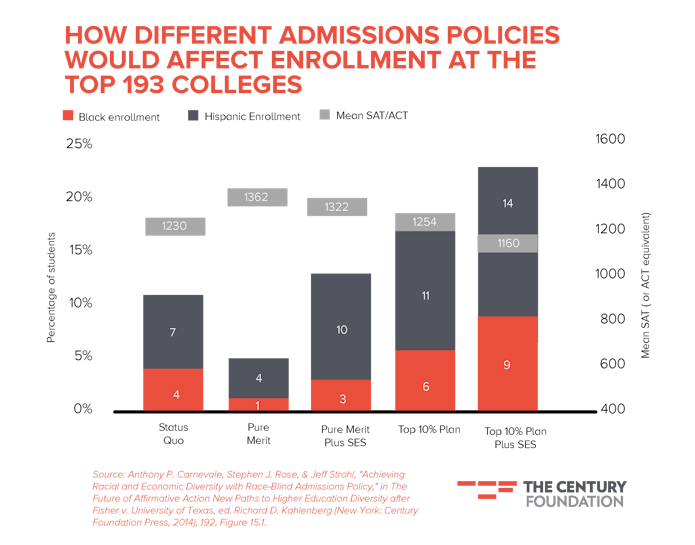

The question then becomes, what would happen if selective universities all played by the same set of rules and could not consider race in admissions? A simulation by Georgetown University researchers Anthony Carnevale, Stephen Rose, and Jeff Strohl shows that combined black and Hispanic enrollment would actually increase under a system using socioeconomic preferences or a top 10 percent plan and SAT scores would remain stable (See Figure 9).

Figure 9

2. Strengthening Community Colleges

Class-based affirmative action at selective colleges will affect a relatively small number of low-income students, so simultaneous efforts should be made to strengthen community colleges, which educate large numbers of students from the aspiring middle class. A 2013 Century Foundation task force on community colleges, co-chaired by Anthony Marx and Eduardo Padron, called for a two-part strategy, drawing inspiration from Brown v. Board of Education: (1)strengthen two-year institutions by drawing students from a broader array of backgrounds and (2) provide adequate financing of community colleges.

Our current system of higher education is growing more and more separate and unequal, paralleling developments in our K–12 system. As access to college has grown, there has, in particular, been a decline in upper middle class representation at community colleges.66 Along with the change in demographics has come a substantial decline in resources devoted to community colleges compared with four-year institutions.67 Trying to make “separate but equal” work in higher education has predictable consequences: while 81 percent of entering full-time community college students wish to ultimately receive a four-year degree, only 12 percent do so after six years.68

The task force called for efforts to make community colleges more like K–12 “magnet schools,” which have offerings attractive to upper-middle-class as well as low-income students. And the group embraced funding formulas based on student needs, so that community colleges would no longer have the fewest resources to educate the students with the greater needs. Although this proposal may sound politically unrealistic, a number of states have adopted outcome-based funding formulas that recognize greater resources should be awarded to institutions that succeed with disadvantaged students. Tennessee, for example, provides a 40 percent funding premium for success with students receiving Pell Grants and is considering raising the premium to 100 percent.69

Will more resources work to strengthen community colleges? Evidence suggests that they will, provided we make the right investments. For example, under the City University of New York’s Accelerated Study in Associate Programs (ASAP), full-time students are provided with a highly structured learning environment that provides extra financial, academic, and career support. According to a rigorous analysis by MDRC, which employed a randomized trial, the program nearly doubled the three-year graduation rate of students, from 22 percent to 40 percent. The program cost 60 percent more per student—about $16,300 more per pupil over three years—yet by boosting results, it actually reduced the amount spent for each college degree by more than 10 percent. Research also finds that investments in smaller class sizes in community colleges, more counselors, and more full-time faculty can improve outcomes for students.70

Addressing Inequality in the Workplace

Finally, efforts to reduce economic inequality for adults—and improve opportunities for their children—cannot ignore the need to address the collapse of organized labor in the United States. Civil rights remedies are needed—as well as other creative new ways to strengthen organized labor.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 (updated in 1991) outlawed racial discrimination in the workplace and in other facets of life, and helped delegitimize racial prejudice. The act needs to be vigorously enforced to address ongoing discrimination, as dramatized by 2003 research finding that job applicants with stereotypically black names are less likely to receive interviews than similar applicants with white-sounding names.71 But we also need to expand civil rights remedies to address a rising problem: discrimination against workers of all races who are trying to form a union.

Although firing an employee for asserting his or her right to unionize is technically illegal under the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), the penalties are so weak that firms routinely flout the law.72 A 2007 study, for example, found that almost one in five union activists could expect to be fired as a result of their organizing activity—a powerful way to get rid of ring leaders and intimidate everyone else.

1. Make Labor Organizing a Federal Civil Right

As Moshe Z. Marvit and I explain in our 2012 book, Why Labor Organizing Should Be a Civil Right, Congress should amend the Civil Rights Act to extend protections against discrimination based on race, sex, religion, and the like to include individuals trying to organize a union. Doing so would give employees a much more powerful tool to combat discrimination than are available under the National Labor Relations Act. Whereas the NLRA gives employees wrongfully terminated the right to back pay and reinstatement, the Civil Rights Act gives employees the right to sue in federal court, engage in legal discovery, and win compensatory and punitive damages and attorneys’ fees.

Politically, the civil rights angle on labor organizing also has benefits. While comprehensive “labor law reform” is seen as a complicated issue that pits unions against employers and has raised complex questions about secret ballot elections, civil rights for labor organizing presents a simple and morally unambiguous issue: Is it fair when a worker who performs his job well is fired for exerting his right to collaborate with others to seek better wages and benefits?

A version of this idea already has been introduced in Congress by Representatives Keith Ellison and John Lewis, who forcefully argue that labor rights are civil rights. If employees were genuinely free to join a union without fear of retaliation by their employers, union organizing could skyrocket. A 2007 study by Harvard labor economist Richard Freeman found that, if workers were provided the union representation they desired, the overall unionization rate would have been 58 percent, compared with the actual rate of 12 percent.73

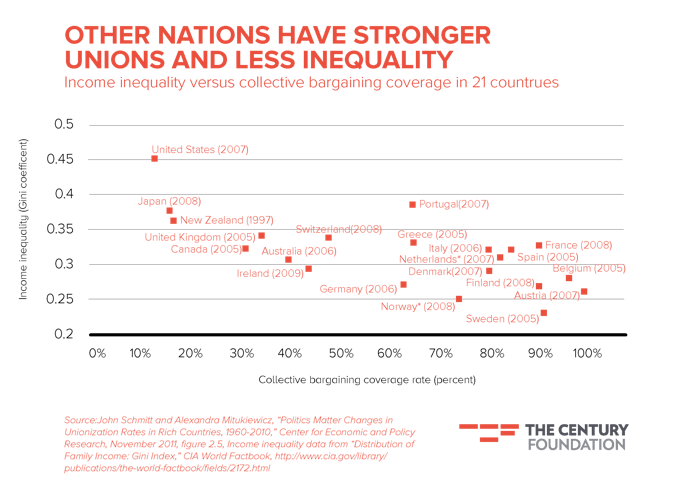

Boosting the ranks of unionized workers, in turn, could help workers bargain for their fair share of productivity gains, which would help reduce income inequality. Vibrant unions also play an important role in democratic societies by serving as a political counterweight to the influence of corporations and wealthy individuals. It is little surprise, therefore, that other advanced nations with stronger union movements have less inequality than the United States (See Figure 10).

Figure 10

2. State and Municipal-level Efforts to Make Labor Organizing a Civil Right

State and local efforts to make labor organizing a civil right in worker-friendly legislative bodies also should be pursued. John Boehner’s House of Representatives is unlikely to move forward on the Ellison-Lewis legislation to support federal civil rights protections for labor organizing, but local and state initiatives might be possible.

Courts have held that the National Labor Relations Act pre-empts state and local labor legislation for employees covered by the act, which may make comprehensive state and local legislation problematic. But there are more than 25 million employees who are not covered by the NLRA who could therefore benefit from making labor organizing a civil right. These non-covered employees include 19.2 million state and local employees, 2.8 million civilian federal workers, 2.7 million agricultural laborers, and more than 700,000 domestic workers.74

State and local action would also build awareness of the proposal and create momentum for a time when a more worker-friendly Congress could take up federal legislation and give workers seeking to organize unions their proper place in the Civil Rights Act.

3. Virtual Labor Organizing

Finally, to address the great economic inequalities Putnam identifies, workers can take their own steps to organize in a way that is not dependent on federal, state, or local legislation. In 2015, Mark Zuckerman, Moshe Marvit, and I outlined a plan for giving rank and file workers the ability to harness technology to organize themselves into unions.

Our policy brief, “Virtual Labor Organizing: Could Technology Help Reduce Income Inequality?” argued that just as people are using technology in new ways—to summon an Uber car, file taxes through TurboTax, or draft a will through LegalZoom—workers should be able to use an app to help them petition the National Labor Relations Board to schedule a union election.

New technology will not reduce employer opposition to unionization, of course, but it can provide a new tool to help workers garner what is the single largest unclaimed legal right to additional personal wealth in America today: the ability to join a labor union. We estimate that, given the well-documented wage premium for joining a union, the average nonunion worker could expect to accumulate an additional $551,000 in wealth by the time she retires by exercising her right to join a union.75

Since the idea was proposed, we have been inundated with calls and e-mails of those wanting to move forward on this concept. The response is one more indication that the high levels of inequality documented by Roger Putnam have reached a tipping point in which people are hungry to advance innovative ways to bring back the American Dream.

Conclusion

America rightly celebrates the victories of “Seneca Falls, and Selma, and Stonewall,” as President Obama memorably put it in his second inaugural address. We should be incredibly proud about advancements for women, African Americans, and gay Americans. But we also need new remedies to advance the rights of low-income and working-class Americans.

As Putnam notes, failing to reach economically disadvantaged kids hurts our efforts to promote economic growth because we waste the talents these students have to offer. It also diminishes our democracy and “violates our deepest religious and moral values.”76 We should thank Putnam for mustering his considerable strengths of analysis to shine critical light on America’s defining issue. Now comes the hard work of answering his call and implementing solutions that are equal to the task. Nothing less than a new civil rights movement for working families is required.

Notes

-

1. Robert D. Putnam, Our Kids: The American Dream in Crisis (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2015).

2. Ibid., 44.

3. Juliet Eilperin and Michelle Boorstein, “In frank language, Obama tackles poverty’s roots,” Washington Post, May 13, 2015, A2; and “Why Obama is Worried about ‘Class Segregation,’” National Journal, May 12, 2015.

4. See Richard D. Kahlenberg, “Immobile in America,” Washington Monthly, March 10, 2015. Portions of this issue brief draw heavily from my Washington Monthly review of Our Kids.

5. Putnam, Our Kids, 18.

6. Ibid., 40.

7. Ibid., 72.

8. Ibid., 70, Figure 2.5.

9. Ibid., 16.

10. Ibid., 7.

11. Ibid., 7 (unions) and 2 (social class).

12. Ibid., 1.

13. Ibid., 38.

14. Ibid., 38–39.

15. Ibid., 217.

16. Ibid., 218–19.

17. Ibid., 39.

18. Valerie Strauss, “One alarming map shows what today’s school ‘reformers’ are missing,” Washington Post, August 25, 2015.

19. Putnam, Our Kids, 166.

20. Ibid., 336 n.69.

21. Richard D. Kahlenberg and Halley Potter, A Smarter Charter: Finding What Works for Charter Schools and Public Education (New York: Teachers College Press, 2014), 58.

22. See, for example, discussion of Heather Schwartz study below.

23. Putnam, Our Kids, 170–71.

24. Ibid., 168.

25. Ibid., 330 n.37.

26. Ibid., 172–73.

27. Ibid., 161.

28. Ibid., 12.

29. Anthony P. Carnevale and Jeff Strohl, “How Increasing College Access Is Increasing Inequality and What to Do about It,” in Rewarding Strivers: Helping Low-Income Students Succeed In College, ed. Richard D. Kahlenberg (New York: Century Foundation Press, 2010), 137, Figure 3.7 and 141, Figure 3.10.

30. Michael Bastedo, “Enrollment Management and the Low-Income Student,” American Enterprise Institute, August 4, 2015; and Paul Fain, “Conference and new research takes a broader look at the college match challenge,” Inside Higher Ed, August 5, 2015.

31. Martha J. Bailey and Susan M. Dynarski, “Inequality in Postsecondary Education,” in Whither Opportunity? Rising Inequality, Schools, and Children’s Life Chances, ed. Greg J. Duncan and Richard J. Murnane (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2011), 121, Figure 6.3.

32. Thomas Geoghegan, Only One Thing Can Save Us: Why American Needs a New Kind of Labor Movement (New York: The New Press, 2014), 170.

33. Putnam, Our Kids, 246.

34. Ibid., 19.

35. Ibid., 34. See also Richard D. Kahlenberg and Moshe Z. Marvit, Why Labor Organizing Should Be a Civil Right (New York: The Century Foundation Press, 2012), 24, Figure 2.1 (using data provided by Lawrence Mishel, Economic Policy Institute).

36. The Global State of Workers’ Right: Free Labor in a Hostile World (New York:Freedom House, August 2010), 10.

37. Putnam, Our Kids, 247–48, 257.

38. Marc Perry, “Can Robert Putnam Save the American Dream?” Chronicle of Higher Education, March 12, 2015.

39. Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs v. The Inclusive Communities Project, Inc. (2015).

40. See 80 Federal Register 42271 (July 16, 2015).

41. I am currently working on a project to develop this idea further. I want to thank Paul Jargowsky, whose comments at an Economic Policy Institute panel on April 10, 2014, triggered my thinking on this issue. See http://www.epi.org/event/patrick-sharkes-paul-jargowskys-work-neighborhoods/.

42. Southern Burlington County NAACP v. Mount Laurel, 67 N.J. 151 (1975), 174, 189, 190 and 212.

43. Fair Share Housing Center, “Mount Laurel Doctrine,” http://fairsharehousing.org/mount-laurel-doctrine/.

44. Putnam, Our Kids, 251–52. See also Douglas S. Massey, Len Albright, Rebecca Casciano, Elizabeth Derickson, and David N. Kinsey, Climbing Mount Laurel: The Struggle for Affordable Housing and Social Mobility in an American Suburb (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2013).

45. David Rusk, cited in Nicholas Brunick and Patrick Maier, “Renewing the Land of Opportunity,” Journal of Affordable Housing 19, no. 2 (2010), http://socialeconomyaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/RenewingtheLandofOpportunity.pdf.

46. Carl Chancellor and Richard D. Kahlenberg, “The New Segregation,” Washington Monthly, November/December 2014.

47. Raj Chetty, Nathanial Hendren, and Lawrence F. Katz, “The Effect of Exposure to Better Neighborhoods on Children: New Evidence from the Moving to Opportunity Experiment,” NBER Working Paper 21156 (May 2015), 2.

48. See Lisa Sanbonmatsu, Jeffrey R. Kling, Greg J. Duncan, and Jeanne Brooks-Gunn, Neighborhoods and Academic Achievement: Results from the Moving to Opportunity Experiment, NBER Working Paper 11909 (January 2006), 18, and 45, Table 2.

49. Chetty, Hendren and Katz, “The Effect of Exposure,” 2–3.

50. Richard D. Kahlenberg, All Together Now: Creating Middle-Class Schools through Public School Choice (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 2001), 35.

51. Ibid., 36.

52. See The Future of School Integration: Socioeconomic Diversity as an Education Reform Strategy, ed. Richard D. Kahlenberg (New York: The Century Foundation Press, 2012), Appendix, 309–11.

53. New York State Education Department, “NYS Schools to Receive Grants to Promote Socioeconomic Integration,” December 30, 2014, http://www.nysed.gov/news/2015/nys-schools-receive-grants-promote-socioeconomic-integration.

54. Kahlenberg and Potter, A Smarter Charter, 9–10; and Richard D. Kahlenberg and Halley Potter, “The Original Charter School Vision,” New York Times, August 30, 2014.

55. Halley Potter, “Lessons from New York City’s Universal Pre-K Expansion: How a Focus on Diversity Could Make It Even Better,” Century Foundation Issue Brief, May 13, 2015.

56. Jeanne L. Reid, Sharon Lynn Kagan, Michael Hilton, and Halley Potter, A Better Start: Why Classroom Diversity Matters in Early Education (New York/Washington, D.C.: The Century Foundation/Poverty & Race Research Action Council, 2015), 15–18.

57. Jeanne L. Reid, “Socioeconomic Diversity and Early Learning: The Missing Link in Policy for High-Quality Preschools,” in The Future of School Integration, 67–125.

58. See Bridging the Higher Education Divide: Strengthening Community Colleges and Restoring the American Dream, the Report of The Century Foundation Task Force on Preventing Community Colleges from Becoming Separate and Unequal (New York: The Century Foundation Press, 2013), 31–33.

59. Halley Potter, “Transitioning to Race-Neutral Admissions,” in The Future of Affirmative Action, 75–90; and Richard D. Kahlenberg, “Introduction,” 9.

60. Richard D. Kahlenberg, A Better Affirmative Action: State Universities That Created Alternatives to Racial Preferences (New York: The Century Foundation, 2012), 6, Figure 2.

61. Anthony Carnevale and Jeff Strohl, “How Increasing College Access Is Increasing Inequality and What to Do About It,” in Rewarding Strivers: Helping Low-Income Students Succeed in College, ed. Richard D. Kahlenberg (New York: Century Foundation Press, 2010), 170, Table 3.7.

62. Fisher v. University of Texas, 113 S.Ct. 2411, 2416 (2013).

63. Marta Tienda, “Striving for Neutrality: Lessons from Texas in the Aftermath of Hopwood and Fisher,” in The Future of Affirmative Action, 97.

64. Tienda, “Striving for Neutrality,” 92.

65. See Richard D. Kahlenberg, “Who Benefits Most from Attending Top Colleges?” Chronicle of Higher Education, March 10, 2011, http://chronicle.com/blogs/innovations/who-benefits-most-from-attending-top-colleges/28852.

66. See Bridging the Higher Education Divide, 20, Figure 2.

67. Ibid., 23, Figure 4.

68. Ibid., 12.

69. Richard D. Kahlenberg, “How Higher Education Funding Shortchanges Community Colleges,” Century Foundation Issue Brief, May 28, 2015, 10,http://www.tcf.org/assets/downloads/Kahlenberg_FundingShortchanges.pdf.

70. Ibid., 7–8.

71. See Marianne Bertrand and Sendhil Mullainathan, “Are Emily and Greg More Employable than Lakisha and Jamal? A Field Experiment on Labor Market Discrimination.” NBER Working Paper No. 9873 (July 2003).

72. Richard D. Kahlenberg and Moshe Z. Marvit, “Want to Realize the Civil Rights Act’s Dream? Apply it to Union Rights, Too,” New Republic, February 16, 2014.

73. Ibid.

74. Richard D. Kahlenberg and Moshe Z. Marvit, “Labor at a Crossroads: Can Broadened Civil Rights Law Offer Workers a True Right to Organize?” The American Prospect, January 12, 2015.

75. Mark Zuckerman, Richard D. Kahlenberg and Moshe Z. Marvit, “Virtual Labor Organizing: Could Technology Help Reduce Income Inequality?” The Century Foundation, 2015, http://apps.tcf.org/virtual-labor-organizing.

76. Putnam, Our Kids, 240.