More than two decades after the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq in 2003, and three years after the United States formally ended its combat mission there, the American military has still not left. The 2,500 U.S. troops in Iraq are a small fraction of the 160,000 stationed there at the height of the American occupation, but even now, Washington operates with minimal coordination with Iraqi authorities.

The festering status quo has serious dangers for both the United States and Iraq—in particular, spiraling and destabilizing military escalation. The U.S. military presence taunts the notion of Iraqi sovereignty, and provides a pretext—and a target—for Iraqi armed groups such as Kata’eb Hezbollah. These groups retain unwarranted legitimacy as long as U.S. troops remain in the country, which weakens the Iraqi government. And when they shoot at U.S. troops with deadly effect and the United States retaliates, it risks sparking a broader conflict.1

Washington has dragged its feet over troop withdrawal because it is clinging to a policy that sees Iraq mainly as an arena for countering Iran. This policy is shortsighted: a sovereign, well-governed, and prosperous Iraq is a much bigger asset to regional stability, to the United States, and—not least—to the Iraqi people. And unless the conflicting interests that define the status quo are resolved, they could quickly destabilize Iraq and draw the United States into war.

This report argues for three main actions to reset the relationship between the United States and Iraq in a way that supports the long-term goals of both countries:

- Redefine and refine the primary purpose of the U.S. military mission in the country as being to assist Iraqi security forces in protecting their territory and preventing any resurgence by the Islamic State or similar groups. (The joint U.S.-Iraqi operation against the Islamic State in August is evidence that there is an organic interest in pursuing these areas of shared interest.)2

- Shift the focus of the U.S.–Iraq bilateral relationship away from security and toward working with civil society, improving governance, and diversifying the Iraqi economy.

- Make a stable Iraqi state the headline goal of all U.S. policy on Iraq, rather than treating the country as being nothing more than a stage for confronting Iran.

Iraqi militias suspended attacks against the United States several months ago, which was supposed to give Iraqi prime minister Mohammed Shia al-Sudani space to negotiate an end to the American-led coalition mission. But although negotiations are ongoing, Washington has made no significant steps toward a change. Each week of inaction provides a new temptation to armed groups, and a heightened risk of a new cycle of violence. It is time to make a course correction.

America’s Intransigence

Since George W. Bush left office in January 2009, successive American governments have seen Iraq as a problem from which they want to extricate the United States, but struggle to do so. The truth is that policymakers in Washington do not see much strategic value in Iraq apart from being an arena to counter Iran. Partly, this American perspective is due to the direction Baghdad’s leaders have taken the country since regime change; but it is also a result of the fact that Iraq, by itself, does not mean very much to the United States’ security or economy. Thus, American policy has been to maintain a military presence in Iraq no matter what—the better to ward off Iran, no matter the costs to the relationship with the Iraqi government. That’s why, when the mission to counter the Islamic State all but ended in 2018, any talk of withdrawing troops was quickly dismissed.

The January 2020 assassinations of Qassem Soleimani, the Iranian Quds Force commander, and Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, the head of Iraq’s Popular Mobilization Units (PMU), led to pressure on the Iraqi government to force foreign troops out.3 But the United States made clear that it would not be leaving.

The American intransigence has been costly, and hasn’t produced an obvious benefit for the United States. In the years since the assassination, Iraqi militias have launched multiple attacks on American facilities inside Iraq and abroad, at times even killing U.S. servicepeople.4 The United States has reacted by launching airstrikes at pro-Iran militia headquarters. Washington has also used drones to assassinate militia commanders it blames for attacks. With each escalatory cycle, the United States risks further enmity and provokes more Iraqi pressure to withdraw its troops and cease military action in Iraq without Baghdad’s consent and in violation of its sovereignty.

As unstable and costly as this dynamic is for all parties, it has persisted. Washington won’t let go of the focus of its Iraq policy: CENTCOM (the U.S. Central command) and the National Security Council don’t want to cede what they view as a strategic outpost for confronting Iran.5 For its part, the Iraqi government is too weak to compel militias not to attack, or to prevent the United States from launching unauthorized military action in Iraq.

Senior politicians in the Coordination Framework (a bloc of Shia parties in the Iraqi parliament that are close to Iran) believe that the way to break this cycle is by ending the U.S. military presence in Iraq, which would prevent any attacks by so-called resistance groups.6 This vision is achievable, if Washington embraces a broader strategy—but it has yet to do so.

Untenable Status Quo

The only way that the United States is able to enact its current Iraq policy is through coercion of the Iraqi state—evidence, by itself, of how unsustainable the current situation is.

Washington uses threats to pressure the Iraqi government not to make a formal request for American troops to withdraw. The threats include economic sanctions, a small dose of which was applied last year, when the Federal Reserve restricted Iraq’s access to dollars because of concerns of illicit currency flows to Iran, Syria and other countries.7 The Treasury Department also regularly announces sanctions against Iraqi politicians, militia commanders, businesses and banks, mostly in connection to Iran.8 Several components of the Iraqi military and security infrastructure depend on the provision of U.S. servicing, such as the Iraqi Air Force, tanks and military vehicles, medium and heavy weaponry, and even communications equipment. All of the revenues from Iraqi oil exports are deposited at the New York Federal Reserve, which essentially holds all of Iraq’s wealth—currently around $130 billion.9 The reality is that Iraq’s economy and security are dependent on the United States, so the Iraqi government does not want to unilaterally expel foreign troops, as much as it would like them gone, for fear of U.S. retaliation of one kind or another.

Sudani is in a difficult position, and can’t resolve the situation on his own. He has bought a few months of stability by advocating for a diplomatic negotiation to end the American military mission in Iraq. So far, Iraqi militias have grudgingly acquiesced to this approach, but there is a limit to their patience. From the militias’ perspective, the only way the United States will withdraw from Iraq is in response to violent coercion. They are encouraged by the American withdrawal from Afghanistan and see a similar pathway to forcing the United States out of Iraq. If the diplomatic approach does not make tangible progress in the near future, it is almost certain that these “resistance” groups will restart attacks against American targets in Iraq and abroad. The ceasefire that Iran pressured Iraqi militias into in February seems to be holding.10 But the threat of escalation is ever near.

On the other side of the equation, the United States has not backed up its talk of a wind-down with any action. It’s true that Washington has announced an intention to end the anti-Islamic State coalition mission, and began negotiations with Iraq through the High Military Commission (HMC), a body tasked with negotiating a suitable evolution of the U.S. presence for both countries.11 But in reality, no meaningful progress has been made concerning whether and when U.S. forces will withdraw. Sudani’s visit to the White House in April was an opportunity to announce some tentative progress and give the negotiations more time, but President Biden does not seem keen to do anything on this issue in the pre-election months.12

According to news reports, Washington and Baghdad have agreed on the outline of a deal under which the United States commits to withdrawing forces from federal areas in Iraq (every part of the country except Iraqi Kurdistan) within a year, and from Erbil in Iraqi Kurdistan within two years.13 However, this timeline seems to be contingent on a continued moratorium of attacks against the United States in Iraq, something the Iraqi government doesn’t control and can’t guarantee. And the heightened tensions in the Middle East and the growing escalation between Israel and Iran have made even the issuing of an outline tricky—in mid-August, Iraq postponed an anticipated announcement of the deal.14

There is no clear sign that the U.S. presidential election will seriously change things in the short run, whatever the outcome. It may be that both Iraq and the United States want to know the results of their respective elections before moving forward (Iraq expects to have its next parliamentary elections in October 2025), passing the buck to future governments.15 Thus, it’s possible that there will be no negotiation milestones for another year and a half. Such a long delay will put pressure on Sudani: militias will say his diplomatic approach has failed, opening up the cycle of escalation again.

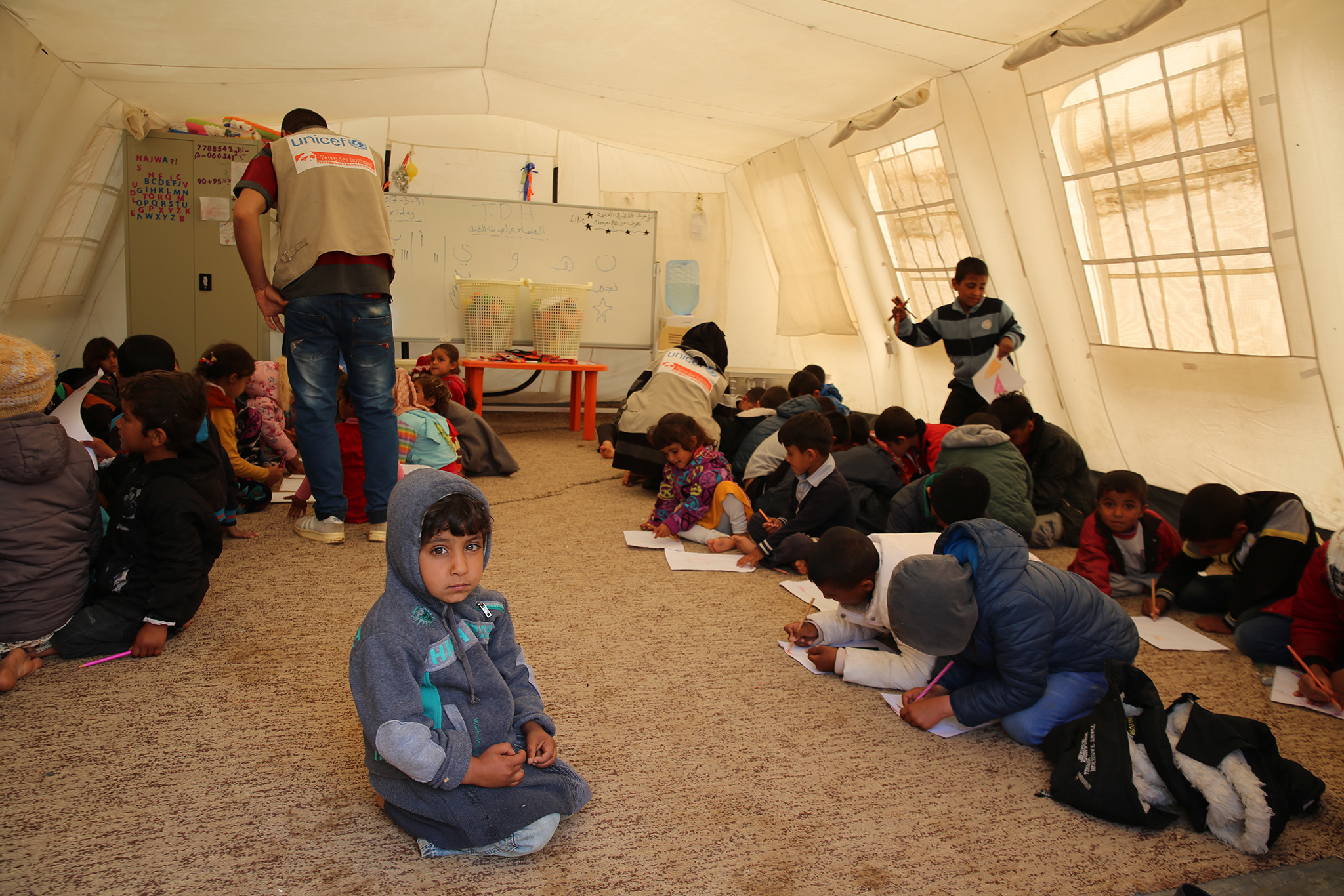

Camp for displaced people in Hasansham, northern Iraq in March 2017. The camp was opened by the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) in November 2016 to help accommodate people displaced from Mosul since the start of the offensive to retake Iraq’s second city from ISIS the previous month. Source: UN Photo/Sarmad Al-Safy, used with a Creative Commons license.

Beyond a Military Focus

Despite all of these challenges, the United States has the ability to chart a better path if it is willing to move beyond a military focus on Iraq. But the United States needs to make the first move, because Baghdad wants to have good relations with Washington, and won’t force a U.S. withdrawal. The United States can ensure a smooth withdrawal—not under fire—by coming up with a plan to scale down its force numbers, formally end the coalition mission, avoid unauthorized military action in Iraq, announce the plan in phases, and credit it to the HMC process. With such a plan, the United States can maintain a significant force protection presence in Baghdad, similar to what it had in 2012–14, when more than a thousand military and special personnel remained in Iraq after the 2011 withdrawal.

But for this plan to happen sooner rather than later, the United States needs to make some progress on troop withdrawal, so that negotiations can continue without the threat of militia attacks. American military and security leaders who remain obstinate about troop drawdowns risk undermining a fragile relationship even further.

The United States can withdraw troops without leaving a security vacuum that Iran will fill. As long as the United States remains engaged with Iraq, Iraq will not completely fall under Iranian influence, even if there are far fewer American troops. An example of such engagement would be supporting Iraq to procure sophisticated air defense systems that would protect it against rockets, ballistic missiles, drones, and fighter bombers, thereby ensuring neither the United States nor Iran (or Turkey, for that matter) can freely conduct military operations in or through Iraqi territory. This type of support would signal goodwill and a commitment to respecting Iraqi sovereignty.

The United States should not need troops to be deployed in a country to have a good relationship with it.

In essence, the United States needs to abandon the idea that it can fight back Iranian influence by using Iraq as an arena for its Iran policy. It also needs to adopt an attitude that is not based on “either we stay or see how long you can survive without us.”’ Iraq should not need to have U.S. troops stationed there to have security, and the United States should not need troops to be deployed in a country to have a good relationship with it. And when the United States withdraws its troops, it should do so in a manner that supports Iraq’s continued stability so that Iraq does not need any future foreign troop assistance, no matter the threat.

Of course, Iraq also has agency—and responsibilities—in the reforming of its bilateral relationship with the United States. Sudani must do more to rein in criminal militias that threaten Iraq’s security and stability and act in contravention to his orders as commander in chief. Senior Iraqi politicians, particularly those from the Shia Islamist parties, need to commit to Iraq’s balanced relations policy, which makes Iraq neutral with regard to neighboring countries, and work to ensure that resistance groups do not undermine the government. Baghdad needs to engage in dialogues with Iran, Turkey, and Syria on preventing instability, addressing security concerns, respecting sovereignty, avoiding sanctions violations, and controlling borders. If Iraq can show the United States that it can control its own territory and not become a source of instability to the region, then it will have a stronger position from which to negotiate what it wants from the relationship.

Considering how fraught the entire Middle East has been in the last few years, Iraq has been surprisingly successful at maintaining its stability. However, the situation could become volatile very quickly, and there is no assurance that, without progress on troop withdrawal, Iraq’s government can go many months of preventing another round of escalation between militias and the United States. It seems logical that the United States would want to help Iraq’s government with maintaining stability, which is why it needs to consider committing to a reduction of troops as soon as is feasible. Right now, the pressure from Iraqi Shia parties who dominate the government is for the United States to reduce its troop presence in the next year. If the United States continues to avoid the question of how to make the reductions, it might end up having to entirely withdraw—probably a worse outcome from the U.S. perspective. It is better for the United States to seriously negotiate, with the intention to substantially and visibly reduce its military footprint in Iraq.

A New Iraq–U.S. Relationship

The United States has already acknowledged that the current military mission in Iraq will eventually end, as recent statements from the HMC meetings make clear. Iraq accepts that some U.S. troops will remain in Iraq to protect its personnel and provide training and support to Iraqi forces. So what should be the basis and principles of ongoing military cooperation and U.S. deployment in Iraq?

Most importantly, the U.S. mission should not be Iran-focused, and must instead be designed to assist Iraqi security forces better protect their territory and prevent any resurgence by the Islamic State or similar groups. The deployment of American troops in Iraq, in a strictly training capacity, should not mean that the United States has the green light to undertake airstrikes and assassinations inside Iraq—things it has ostensibly done as self-defense, but which in reality have been part of its anti-Iran policy. Focusing on the Islamic State will keep the U.S. mission aligned with the missions of other countries from NATO and beyond, which are aimed solely at assisting Iraqi forces. This focus will involve training and support of the Iraqi army, Federal Police, border guards, and, most crucially, the Counter Terrorism Service. Investing in and supporting these state-centered security institutions will act as a counter to groups in the PMU that act outside the rule of law.

Secondly, the bilateral relationship must move its focus away from security and toward working with civil society, improving governance and the professionalism of state institutions, and helping Iraq diversify its economy by using American experience with finance, technology, entrepreneurism, and innovation. This kind of support does not need significant funding: Iraq is a rich country that shouldn’t need financial aid, but it does require consistent engagement and a willingness to work in a tough operating environment. If the United States does more to help Iraq develop and catch up with its neighbors, it will ensure a much more sustainable relationship and public support, far more than any military mission can.

Finally, the basis of any future Iraq policy should be the aim of maintaining a stable state. Iraq is sovereign and one of the few democracies in the Middle East. It is not a U.S.-occupied dependency, nor is it under UN tutelage. It is a lynchpin in the region, the second largest exporter of oil in OPEC, and a diverse country that borders key countries such as Iran, Turkey, Syria, and Saudi Arabia. Helping Iraq become a regional model of pluralistic, democratic governance and of federalism should be an elementary goal. The United States and Iraq share an interest in countering the Islamic State and other violent extremists, preventing state collapse, and maintaining a regional balance between Turkey, Iran, and Saudi Arabia.

In recent years, Iraq has become more capable and less dependent on the United States than it was in the post-invasion years of 2003–8. But the structure of the U.S.–Iraq relationship has not caught up. It is time for the United States to evolve out of its fixation on Iraq as an arena for competition with Iran. Instead, Washington should see the country as a potential long-term ally. And Iraq should be able to continue to pursue a solid relationship with Iran, as many other countries do.

A new U.S. plan should announce that remaining troops are operating under a new mission at the invitation of the Iraqi government, and that the United States commits to respecting Iraqi sovereignty.

The best way forward for both countries would ideally start with an announcement that the counter-Islamic State coalition has ended and some American troops are being withdrawn. This announcement would also explain that the remaining troops are operating under a new training and assistance mission at the invitation of the Iraqi government, and that the United States commits to not taking actions that violate Iraqi sovereignty. Next, the Iraqi government would respond by guaranteeing the safety of all foreign missions and starting a concerted campaign to rein in illegal militia activity.

After both sides meet these milestones and stability is maintained for some period of time, the parties should announce a program based on the Strategic Framework Agreement, signed in November 2008, which normalized the post-2003 U.S.–Iraq relationship. This program should meet shared goals in Iraq and should mostly focus on economic development and improving governance. It could include support for Iraq to join the World Trade Organization; training, exchange programs, and technology for local government administration; the deployment of green energy initiatives; and better management of natural resources. The United States should condition any such program on Iraq achieving milestones—such as reducing gas flaring and carbon emissions, diversifying revenue sources, and reducing corruption—to open up further engagement and support. Such conditions would give Iraq more incentives to work with the United States in furthering reforms and development.

What America Really Needs

Given the current gap between U.S. and Iraqi goals, it’s likely that the status quo will be maintained in the short term. Both parties are likely to continue with slow negotiations while postponing dealing with all the matters raised in this report, due to their own domestic political pressures. This short-termism is unfortunate, and hazardous: continued American troop presence could provoke a new, more dangerous round of fighting between militias and U.S. forces, at a time of extreme regional volatility. Such flare-ups could trigger a regional conflict, or the involvement of the United States in a hot war that it doesn’t want, and which could lock Washington in an escalatory spiral.

For now, the Iraqi government seems to be content with merely negotiating reductions in the U.S. troop presence and a formal termination of the U.S.-led coalition to counter the Islamic State. The United States is broadly on board with these goals, but wants to pursue them on its own timeline, and not while under fire from pro-Iran militias.

But that’s about as far as the negotiations go right now. There has been no real discussion about how to develop the bilateral relationship, something that requires some difficult decisions on both sides, and is being held back by mutual distrust and fears about security and stability in Iraq and the region.

Ending Saddam Hussein’s rule and occupying Iraq in 2003 cost a staggering amount of blood and treasure for the United States and, all the more, for Iraq. It would be folly to now throw out an opportunity to reap the benefits of regime change that U.S. policymakers once hoped for: an Iraq that is friendly to U.S. interests and supports security in the region. These goals are achievable, but only if Washington accepts that, as it helps Iraq become permanently stable, it will not necessarily agree with Baghdad on everything.

If, on the other hand, the United States is incapable of envisioning a future for Iraq without U.S. troops being based there, there are serious risks of further instability and an inevitable backlash against the United States—at a time when war could engulf Iraq and consume the region at a moment’s notice.

With a better Iraq policy, the United States could cultivate something that it badly needs, and which is in short supply: a friendly, stable, and democratic country in the Middle East.

This report is part of “Networks of Change: Reviving Governance and Citizenship in the Middle East,” a Century International project supported by the Carnegie Corporation of New York and the Open Society Foundations.

Header Image: President Biden and Iraqi Prime Minister Mohammed Shia al-Sudani shake hands in the Oval Office of the White House on April 15, 2024 in Washington, DC. Source: Anna Moneymaker/Getty Images

Notes

- “U.S. Carries Out Strike in Iraq as Regional Tensions Worsen,” Reuters, July 30, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/explosions-iraqs-pmf-security-agency-base-south-baghdad-kill-one-member-sources-2024-07-30/.

- Eric Schmitt, “U.S. and Iraqi Commandos Targeted ISIS in Sprawling Operation,” New York Times, September 3, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/09/03/us/politics/iraq-commandos-isis.html?searchResultPosition=1.

- “Iraqi Parliament Votes for Plan to End Us Troop Presence in Iraq after Soleimani Killing,” CNN, January 5, 2020, https://www.cnn.com/2020/01/05/world/soleimani-us-iran-attack/index.html.

- “Three American Soldiers Killed in Drone Strike in Jordan, U.S. Says,” New York Times, January 29, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/01/29/us/politics/us-troops-drone-attack-jordan-iran.html.

- “Statement of General Michael ‘Erik’ Kurilla on the Posture of U.S. Central Command,” CENTCOM, March 7, 2024, https://www.centcom.mil/ABOUT-US/POSTURE-STATEMENT/.

- “Iraqi Armed Factions End Truce with American Forces,” Asharq Al-Awsat, June 21, 2024, https://english.aawsat.com/arab-world/5032820-iraqi-armed-factions-end-truce-american-forces

- “Targeting Iran, U.S. Tightens Iraq’s Dollar Flow, Causing Pain,” Associated Press, February 2, 2023, https://apnews.com/article/united-states-government-iraq-business-0628bad5e4d46315951c90681baba202.

- “U.S. Accuses Iraqi Bank of Serving as Conduit for Terrorism Financing,” The National, January 29, 2024, https://www.thenationalnews.com/world/us-news/2024/01/29/us-sanctions-iraqi-bank-accused-of-serving-as-conduit-for-terrorism-financing/.

- “U.S. Warns Iraq It Risks Losing Access to Key Bank Account if Troops Told to Leave,” Wall Street Journal, January 11, 2020, https://www.wsj.com/articles/u-s-warns-iraq-it-risks-losing-access-to-key-bank-account-if-troops-told-to-leave-11578759629.

- “Pro-Iran Iraqi Groups Agreed to Conditional Truce with U.S.,” The New Region, August 13, 2024, https://thenewregion.com/posts/776/pro-iran-iraqi-groups-agreed-to-conditional-truce-with-us-paramilitary-source.

- “U.S., Iraqi Officials Hold Pentagon Meeting to Discuss Security Cooperation,” U.S. Department of Defense, July 22, 2024, https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/3845967/us-iraqi-officials-hold-pentagon-meeting-to-discuss-security-cooperation/

- “Iraq Says Announcement on Date for End to U.S.-Led Coalition Mission Postponed,” Reuters, August 15, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/iraq-says-announcement-date-end-us-led-coalition-mission-postponed-2024-08-15/.

- “Iraq, U.S. Reached Deal to Withdraw Troops in Two Years,” The New Region, August 8, 2024, https://thenewregion.com/posts/766/iraq-us-reached-deal-to-withdraw-troops-in-two-years-sources.

- “Iraq Postpones Plans for U.S. Troop Withdrawal amid Regional Tensions,” CNN, August 15, 2024, https://www.cnn.com/2024/08/15/middleeast/iraq-operation-inherent-resolve-end-intl-latam/index.html.

- “Talks to End U.S.-Led Coalition in Iraq May Take until after U.S. Election, Iraqi Official Says,” Reuters, March 12, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/talks-end-us-led-coalition-iraq-may-take-till-after-us-elections-source-2024-03-12/.