The COVID-19 pandemic unleashed an unprecedented wave of unemployment impacting a wide variety of Americans, from those who lost jobs when small retail businesses closed in the wake of necessary restrictions to caregivers forced to quit work when their children’s school switched to virtual learning. Starting with the CARES Act, the U.S. government took bold policy actions so that workers impacted by this epochal pandemic would not suffer long-term economic damage.1

In particular, regarding unemployment insurance, the federal government initiated three major programs:

- Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA), which allows traditionally ineligible workers (including gig workers) and others who lost work due to COVID-19 to receive aid.

- Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation (FPUC), which provided $600 per week at first, and later $300 per week, to supplement the meager unemployment benefits amount provided by states—$334 per week on average—when the pandemic-induced jobs crisis erupted in spring 2020.

- Pandemic Extended Unemployment Compensation (PEUC), which grants additional weeks of benefits to those who are still jobless when they exhaust their state benefits (which typically last twenty-six weeks).

Congress supported several other critical programs, including Mixed Earners Unemployment Compensation ($100 per week extra for those workers whose labor was split between being an employee and being an independent contractor), and 100 percent federal funding for expansion of the existing Federal–State Extended Benefits (EB) program (an extra thirteen to twenty weeks of benefits in high unemployment states) and for work-sharing benefits (partial benefits for those workers who were kept on part-time by their employer).

Passed in the middle of March, the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) continued all of these critical programs.2

- The maximum duration of PEUC benefits have been increased from twenty-four to fifty-three weeks.

- The maximum duration of PUA benefits were increased from fifty to seventy-nine weeks. Those in high unemployment states could receive up to eighty-six weeks of benefits.

- The $300 in additional FPUC benefits to all of those on unemployment also remained in place.

Taken together, these programs have delivered nearly $800 billion in assistance to families over the course of the pandemic. But this aid will soon abruptly come to an end. Under current legislation, FPUC, PEUC, and PUA benefits can be paid through the week ending September 5, 2021, but after that, all of this federal assistance will be cut off on September 6, with no grace period. Furthermore, in an unprecedented turn of events, twenty-six states announced that they would end these 100 percent federally paid benefits early. This controversial move—already ruled to be in violation of state law in three states (Arkansas, Indiana, and Maryland)3 and subject to ongoing litigation in other states—has somewhat distracted the nation’s attention from the far larger impact of the looming benefits cliff coming in September, which will affect all states, including the nation’s largest, where the pandemic has had the most sizable impact on the labor market. With the U.S. economy still short 6.5 million jobs as of the end of June 2021, the end of the pandemic unemployment benefits will be an abrupt jolt to millions of Americans who won’t find a job in time for this arbitrary end to assistance.4

Who Will Be Hurt Most by the September 6 Cutoff of Federal Pandemic Unemployment Benefits?

The U.S. economy is recovering from the deep wound of the pandemic jobs crisis, but millions of workers are still unemployed. Furthermore the impact of the jobs crisis has hit American workers unevenly, with some social and geographic sectors hit harder than others. Because unemployment benefit levels vary greatly from state to state, the ending of federal benefits will have a far greater impact where traditional state benefit levels are the lowest.

7.5 Million Workers Will Lose All Benefits on Labor Day, September 6, 2021

As of the week of July 10, there were a total of 9.3 million Americans relying on one of the two main pandemic unemployment programs (5.1 million on PUA and 4.1 million on PEUC). As the recovery has moved forward, this total has declined steeply from 13.8 million at the end of February, and that decline is predicted to continue through the rest of the summer. Map 1 present (and Appendix Table 1) provide estimates of how many of these workers will remain unemployed as of September 6 when the benefits will no longer be available. These estimates are based on the flows on these programs, current caseloads, and the rate in which workers have been estimated to have been exiting the programs.5

Based on rates of reemployment and when workers entered the program, our model predicts that there will be 7.5 million workers on these two programs when they come to an end. This includes:

- 4.2 million workers on the PUA program. By definition, these workers are not eligible for any form of federal and state unemployment compensation, including many self-employed individuals and gig workers—and thus will be out of options once the PUA program ends. The largest group is in California (more than 1 million workers), but there are more than 150,000 individuals impacted as well in the states of Indiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, and Pennsylvania.

- 3.3 million workers who would lose benefits being provided through the PEUC program. California is again the largest impacted (900,000), but the states of Florida, Illinois, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania also each have 125,000 workers subject to an abrupt loss of benefits. A share of workers on PEUC will be able to go back on traditional state unemployment benefits, but at a lower rate than before, if they have worked intermittently since they were first laid off in 2020.

Throughout the pandemic, workers exhausting PEUC benefits have been eligible for the Federal–State Extended Benefit program, which provides an additional thirteen to twenty weeks of benefits, but this program will be largely out of reach for jobless workers after September 6, 2021. While there are ten high-unemployment states currently eligible for this program, six of those ten states are participating only on the condition of receiving 100 percent federal funding. As of September 6, we predict that only Alaska, Connecticut, New Jersey, and New Mexico will be able to transition exhausting PEUC recipients onto EB, but with 50 percent state funding. Even in these states, not all workers exhausting PEUC in September will be able to go on to EB because some on PEUC now have already received EB earlier in the pandemic.

Map 1

Source: TCF analysis of U.S. Department of Labor data.

Workers of Color Will Suffer Most From the Cutoff of Unemployment Benefits

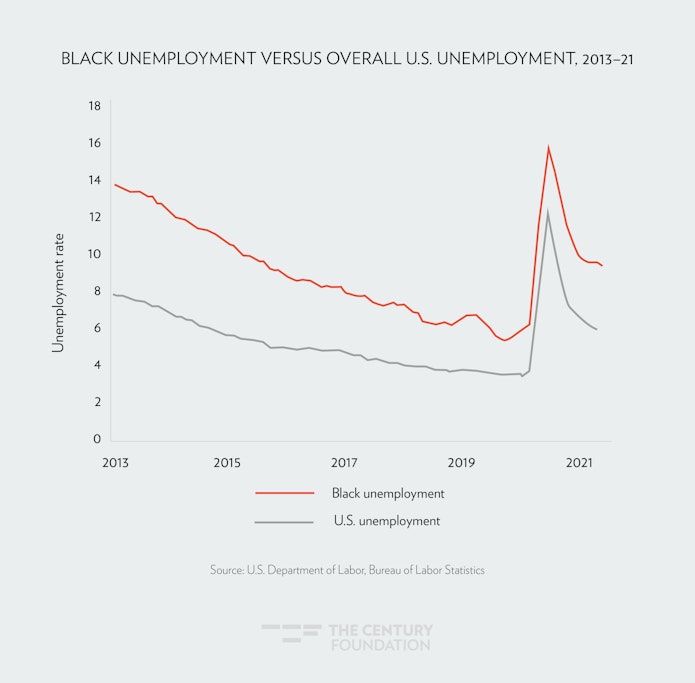

Workers of color, concentrated in frontline industries, bore the brunt of the COVID-19 labor market crisis and are still suffering the most. The current unemployment rate for Black workers is 9.2 percent—a rate that would likely be declared a national emergency if it were impacting the entire population.

figure 1

Moreover, the policymakers have an opportunity to learn from the mistakes of the Great Recession, above all cutting off federal support too early in the recovery. In 2013, when aid to the long-term unemployed was cut off, the Black unemployment rate was well over 10 percent and the national rate was elevated too. The long, slow recovery was particularly painful for Black workers. Right before the COVID-19 crisis, the gap between Black unemployment and overall U.S. unemployment had narrowed substantially. (See Figure 1.) A fast recovery—supported by continued fiscal support—would bring us back to that more inclusive labor market sooner than after the Great Recession.

We are far from an inclusive labor market today. The Black unemployment rate has remained nearly twice as high as the white unemployment rate of 5.2 percent. Asian workers (5.8 percent) and Latinx workers (7.4 percent) also remain out of work at higher levels than white workers.6 While data on the racial background of workers on unemployment is limited, available data indicate that an average of 18.3 percent of those who turned to their states for unemployment benefits during the pandemic were Black, compared to 12.3 percent of the pre-pandemic workforce in the states.7 There are more Black workers on benefits despite the fact that they were more likely to be denied assistance than white workers—so the disparity in need is even greater than these statistics indicate.8 As pointed out by Dr. Bill Spriggs in the New York Times, the delay in hiring is not an issue of education (white high school dropouts have fared better in the recovery than Black workers with an associates degree) or active searching for work, but rather the continued reality that Black workers are typically first fired and last hired.9 The end of pandemic unemployment benefits means that these workers won’t have access to financial assistance to carry them through a longer road to reemployment than white workers are receiving.

Women and Other Caregivers Will Lose Crucial Support Getting Back to Work

For the first time ever, Congress took dramatic action to ensure that caregivers who lost jobs during the pandemic due to their responsibilities taking care of children or family members ill with COVID-19 would receive assistance. Because of these challenges, there are still 1.79 million women who have dropped out of the labor force during the pandemic.10 Because they were not laid off, these workers are not eligible for traditional state unemployment benefits, but can receive federal PUA. With access to PUA gone, these workers will have no aid as they search for work.

1.2 Million Additional Workers Will Lose Benefits in States that Cut Programs Early

Millions of additional workers will be impacted by the ending of pandemic unemployment benefits. Nineteen states have already cut off PUA and PEUC. (See Table 1.) A total of twenty-six states moved to end at least one of the pandemic unemployment programs, but state judges reversed the decision in Indiana, Maryland, and Arkansas, and Alaska, Arizona, Florida, and Ohio remained in the PUA and PEUC programs.11 While the list includes many of the smaller states in the Midwest and Mountain West, our model estimates there will be 1.25 million workers cut from assistance in these states and who will have not found a job as of September 6. (This total is in addition to the 7.5 million mentioned above.) Moreover, the plight of these workers exposes the flaws of delivering federal unemployment aid through a system that depends on state discretion. As decisions in the flurry of lawsuits following the announcement of state cuts show, the governors in these states are having trouble following their own state laws when it comes to unemployment. Future federal unemployment reform should make participation in federal extended and enhanced benefits a requirement on par with other requirements outlined in the Social Security Act and Federal Unemployment Tax Act.

Table 1

| Workers Still Unemployed in States Cutting All Federal Unemployment Benefits Early | ||

| State Cutting Off Benefits Early | Date Cut Off | Still Unemployed as of September 6 |

| Alabama | June 19 | 44,095 |

| Georgia | June 26 | 90,455 |

| Idaho | June 19 | 5,965 |

| Iowa | June 12 | 22,290 |

| Louisiana | July 31 | 159,687 |

| Mississippi | June 12 | 33,707 |

| Missouri | June 12 | 64,793 |

| Montana | June 26 | 15,145 |

| Nebraska | June 19 | 5,815 |

| New Hampshire | June 19 | 8,305 |

| North Dakota | June 19 | 5,934 |

| Oklahoma | June 26 | 29,937 |

| South Carolina | June 26 | 76,463 |

| South Dakota | June 26 | 1,155 |

| Tennessee | July 3 | 77,792 |

| Texas | June 26 | 579,821 |

| Utah | June 26 | 9,465 |

| West Virginia | June 19 | 17,071 |

| Wyoming | June 19 | 3,673 |

| Total | 1,251,568 | |

| Source: Century Foundation analysis of U.S. Department of Labor data. | ||

Lastly, there are still more than 3 million workers receiving the $300 boost to their state unemployment benefits through FPUC.12 The end of this aid will quickly reduce the economic value of unemployment benefits. If 3 million workers per week were to eventually lose the $300, this will remove over $3.5 billion in purchasing power from the economy each month. In California, the boost from the $300 FPUC payments has increased the wage replacement provided by state unemployment insurance benefits from 34 percent to 67 percent.13 The effectiveness of FPUC in supporting state and local economies points to a very real problem that needs to be solved—the low level of state unemployment benefits that necessitated FPUC in the first place. Senators Ron Wyden (D-OR) and Michael Bennet (D-CO) released a discussion draft that proposed a permanent replacement rate of 75 percent for unemployment benefits, in every state and with no ability for states to opt out.14 This is the kind of reform that is needed.

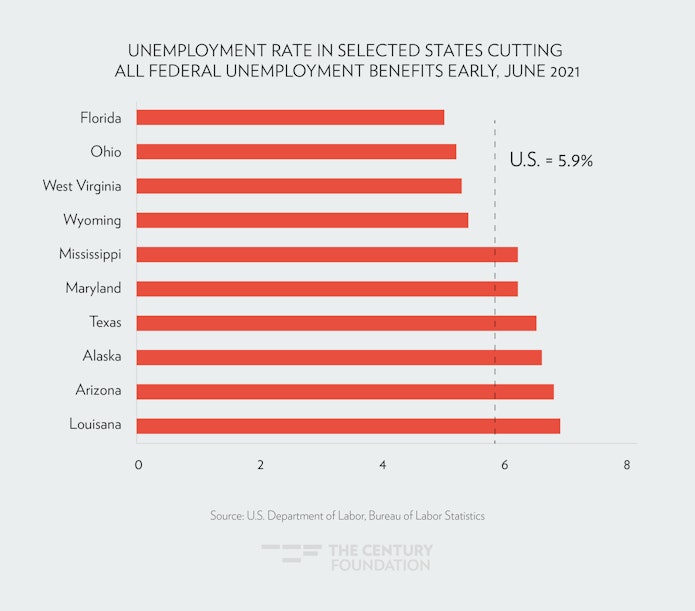

Governors in the states that cut off unemployment early argued that the jobless benefits were keeping people from returning to work and had led to labor shortages in their states. The unemployment rates in the initial states that announced an early end to benefits was notably below the national average. However, better “economic conditions” did not broadly justify ending federal programs early. In fact, six of the states had unemployment rates in June above the national average, and another four were at or above 5 percent unemployment. (See Figure 2.)

figure 2

Moreover, Texas, Florida, and Ohio—the three largest states in the group—are among those with elevated unemployment rates. Politics, not economics, drove the attack on unemployment insurance.

The Benefit Cutoff Is Coming Too Early

Senator Wyden, chair of the Senate Finance Committee, has spoken out in favor of tying the continued delivery of “pandemic unemployment benefits to economic conditions.”15 When it comes to economic conditions, there are numerous data points that support the argument for continued unemployment benefits. The unemployment rate is at 5.9 percent—still 1.7 times higher than the unemployment rate before the pandemic, 3.5 percent in February 2020.16 Furthermore, the situation is far worse than the current unemployment rate reveals: 42 percent of unemployed workers have been out of work for six months or more, compared to 19.3 percent in February 2020—a level that matches the very worst period of the Great Recession in 2011. While there are 9.5 million Americans officially unemployed, the Economic Policy Institute finds that there are another 10.4 million workers still suffering from the unemployment downturn as of June including 4.4 million individuals who have dropped out of the labor force altogether.17

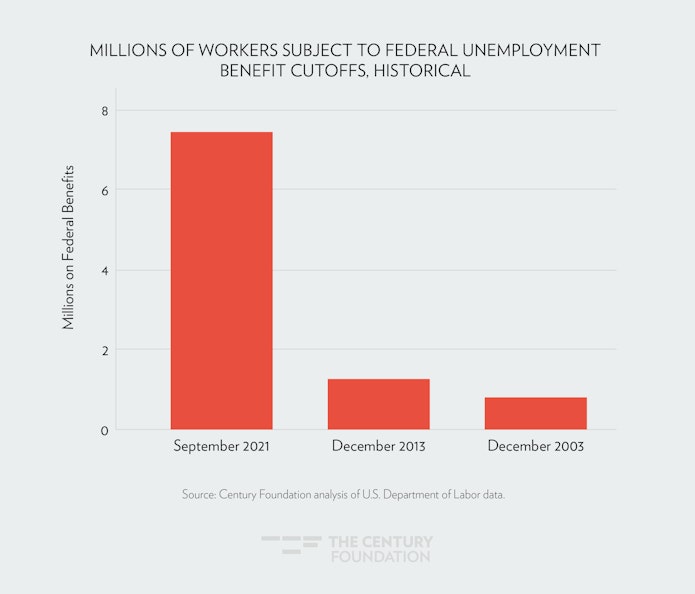

The current elevated level of unemployment claims provide the most compelling evidence of why today’s economic conditions require continued federal unemployment benefits. Figure 3 compares the number of workers projected to be cut off from federal unemployment benefits in September to the previous two times when Congress let extensions expire. In December 2013, there were just 1.3 million workers remaining on Emergency Unemployment Compensation—one sixth of the current total of workers impacted by the looming cutoff of PEUC and PUA. The EUC program was subject to the same withering criticism that it was “paying people not to work,” because it offered ninety-nine weeks of benefits.18 Yet, Congress passed a bipartisan extension of these programs in December 2012, when there were only 2.1 million workers on the program—far fewer than will be cut off this coming Labor Day.19 Similarly, President George W. Bush averted suffering in the far milder recession that started in 2001 by signing a law putting in place the continuation of Temporary Extended Unemployment Compensation when there were only 777,000 workers remaining on benefits in December 2002 and there were still just 820,000 on benefits when was phased out in December 2003.20 The stark gap between the current situation and these recent historical examples makes the current silence of federal policymakers difficult to understand.

Figure 3

Unemployment Benefits Are Not Holding Back the Labor Market Recovery

Concerns about the negative impact of unemployment benefits on unemployed workers’ motivation to find jobs have been a feature of policy debates for decades, with conservatives routinely complaining that unemployment benefits are paying people to not work. These longstanding arguments have come into the forefront as the opening of state economies and the progress in the vaccination program have led to a major increase in the number of job openings nationwide, and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce called for an end to enhanced unemployment benefits due to the relatively slow April jobs report.21

Concerns about a Drag on Job Seeking Have Been Largely Exaggerated

Job growth has bounced back tremendously, with the economy adding 850,000 jobs in June, which was the best report since last August and stood out as the third-best month of job growth compared to pre-COVID times going back to 1938, when data began to be collected.22 While there was major anxiety from the slower than expected net job growth in April 2021 and an increase in unfilled job openings in April as well, the growth in unfilled job openings had stopped cold by May, and the payroll numbers reflected the process of return to work by June.23 This is part of a natural process that is to be expected. The situation is similar to the experience at an airport when multiple planes let out and shuttle busses queue at the terminal to bring passengers to their destinations—there are lots of seats available, but it takes time for them to get filled up. Millions of workers lost jobs over the past year and a half and many of them were laid off from businesses that permanently closed due to the pandemic. As most job seekers have personally experienced, it can take weeks, even months, to search for a job, and during the pandemic, that is further complicated for many workers whose search for work only became realistic once the vaccine became available and the economy was able to begin to open.

Economic Studies Confirm That the Disincentive of Unemployment Benefits Is Limited

Throughout the pandemic, economic studies have found little meaningful impact of extra unemployment pay on employment. Yale scholars concluded that the initial $600 extra in aid did little to dampen job-finding, and a detailed review by the J.P. Morgan Institute found no uptick in job-finding24 when all additional federal unemployment assistance was eliminated between September and December.25

There’s no evidence that the early cutoff of unemployment benefits has led to an increase in hiring in those states. Economist Arin Dube analyzed the most recent Census Bureau data and found that 2.2 percent of adults in these states stopped receiving benefits, but the percentage of workers in these states that were employed actually declined by 1.4 percent. Similarly, Peter Ganong of the University of Chicago analyzed the June state employment report and found no statistical difference in the change in payrolls between May and June in states that had cut off aid and states that did not.26 Finally, economist Aaron Sojourner found that state unemployment claims27 were already decreasing in cutoff states before they made the announcement, and since the announcements, rates of decline have been equal between those states that had announced cutoffs and those who had not. Even Goldman Sachs economists found no clear evidence that the cutting off of federal benefits led to significantly more hiring.28

The Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco produced an important study that found that the $300 additional benefits could potentially reduce job finding in a way so that “about seven out of 28 unemployed individuals receive job offers that they would normally accept [each month] but one of the seven decides to decline the offer due to the availability of the extra $300 per week in UI payments.”29 The real issue is that, in either scenario, twenty-one workers are still without a job and need support; removing all unemployment benefits torpedoes the wellbeing of those twenty-one workers simply to encourage that one additional worker to accept a job.

Extending Benefits Did Not Worsen Unemployment during the Great Recession

The critical issue now is not whether to add the $300 benefit, but whether to keep unemployment benefits going at all. The experience of the Great Recession—when benefits could last as long as ninety-nine weeks in some states but far shorter in others—provided researchers with fertile ground to test whether extensions of benefits could negatively impact job finding. A detailed economic study of metropolitan areas that crossed state lines found that employment did not grow more slowly among residents in counties offering more in unemployment benefits.30

The Problem Is the Quality and Diversity of Job Openings, Not the Quantity

As in other recoveries, the jobs added in the early stages of recovery from the pandemic have been those at the low end, as restaurants and other service sector businesses reopened and hired workers at low wages and with limited benefits. The Economic Policy Institute’s Elise Gould found that there are more job openings in the accommodation and food services sector than there are workers laid off from that sector.31 Indeed, the UC Berkeley Food Labor Research Center found that many workers had left the restaurant sector due to concerns about pay and safety during the pandemic.32 However, better paid sectors such as information, education, arts and entertainment, and real estate have had more unemployed workers than job openings. One of the goals of unemployment benefits is to enable workers to have the chance to search for a suitable job at good pay, rather than be forced into jobs that don’t utilize their skills and become a dead end. This goal is especially valuable at a time when workers remain deeply concerned about contracting COVID-19, which is an especially valid concern in regions where vaccination rates are low and even vaccinated people are at risk.

The End of Unemployment Benefits Will Actually Slow Economic Growth

Unemployment benefits are still pumping over $6 billion per week into the economy.33 With the cutoff of additional benefits, that number will crash down to $1 billion per week. Unemployment benefits have one of the highest multiplier effects (a return of $1.61 for every $1 spent) of any form of government spending, and the end of this stimulus will slow the progress of the economy returning to its pre-pandemic trajectory.34 Personal income fell by 27 percent in the second quarter, after increasing 63 percent in the first quarter, leading to GDP growth that was strong but nonetheless fell short of Wall Street projections.35

The Delta Variant Is Complicating the Recovery

After dropping down below 10,000 earlier in the month, the new COVID-19 case count surged to nearly 125,000 in a single day by the end of July. While most prognistactors are not convinced that Delta variant will stop the forward momentum of the economy, it does complicate the jobs recovery.36 New indoor mask mandates in places such as Los Angeles and fears of infection may curb the resurgence in service sector demand and the need for workers, and the global struggle to contend with a more contagious variant continues to complicate global supply chains and the U.S. businesses that rely on them.37 Moreover, the Delta variant will contribute to legitimate fears among the unemployed that they will not be safe returning to work until the vaccination drive has reached a larger share of the populace. The resurgence of COVID-19 through this variant means that the United States certainly won’t be past the danger of COVID-19 by fall, but still will be ending key pandemic unemployment benefit programs by then.

Policy Recommendations

As the pandemic unemployment benefits cliff approaches, there are several things that can be done at the federal and state levels to ensure a softer landing for the 7.5 million workers currently facing the cutoff of all federal unemployment insurance benefits.

Federal Policy Created the Cliff, Federal Policy Can Fix it

The sudden cliff in unemployment benefits is a result of several policy flaws. First, there are no effective mechanisms for unemployment benefits to fulfill their role as an economic stabilizer by automatically triggering more generous benefits when times get worse. The Federal–State Extended Benefits Program is supposed to play this role, but because it relies on state funding, most states don’t fully participate in a program to provide longer benefits when the total unemployment rises.38 As a result, Congress was forced to rely on temporary pandemic programs with multiple arbitrary dates that took up much of Washington’s attention at the end of 2020 and again in March. Moreover, Congress’s effort to patch up the limited eligibility of traditional benefits with PUA forced states to rapidly roll out new application technologies that were vulnerable to fraud. Finally, Congress in 2020 could only ask states to implement a PUC program that paid out a flat amount because states could not feasibly adjust benefit formulas without delaying the payment of aid by months. These problems illustrate the need for a comprehensive permanent reform of unemployment that includes automatic triggers and requirements for more generous benefits. Moreover, Congress should enact a permanent Jobseeker’s Allowance. This idea, first proposed by Georgetown University, The Center for American Progress, and the National Employment Law Project in 2016 would provide a lower tier of federally funded unemployment assistance to those who do not qualify for traditional unemployment benefits.39 All of these ideas have been embraced by leading advocacy organizations, were part of a discussion draft circulated by Senators Ron Wyden and Michael Bennett, and most were discussed in the FY 2022 Biden administration budget. The expected budget reconciliation plan to enact President Biden’s American Families Plan provides a critical opportunity to move in the direction of permanent unemployment insurance reform so as not to leave the workforce in the situation of facing a drastic cutoff of assistance.

On July 29, the Biden administration called on Congress to extend the eviction moratorium just two days before it expired, which wasn’t enough time to prevent the chaos the looming expiration caused.40 While there may not currently be political will to continue pandemic unemployment benefit programs, the pressure may grow as a similar deadline approaches. Congress and the Biden administration should start planning now and consider various options for a temporary renewal of some or all of the pandemic unemployment programs until the end of the year, when a far greater share of workers should be able to find work, vaccinations will have reached their goal in more states, and the impact of the Delta variant will be better understood and the economy will be able to respond accordingly.

States, with the Help of the U.S. Department of Labor, Should Be Prepared to Help Those with Expiring Benefits

Whether or not federal benefits are extended, there are several steps that states can take to ensure their unemployed workers have a softer landing when their federal unemployment benefits expire:

- Targeted aid to the unemployed. The U.S. Department of Labor should work closely with states to manage the flow of information and available assistance to the record number of unemployed losing benefits. The Department of Labor should urge states and local entities to find novel ways to provide financial assistance to exhaustees, through the use of WIOA needs-related payments or state additional benefits for those who opt for retraining, or by using state and local relief to provide additional unemployment benefits or other forms of cash assistance. For example, fiscal relief can be used for the payment of unemployment benefits and could make it easier for high unemployment states to continue participating in the EB program once 100 percent federal funding is removed. Moreover, states should be directed by the Department of Labor to require American Job Centers using Wagner-Peyser Act Employment Service (ES) and WIOA grant funds to contact individuals losing benefits, and for those unemployed without job prospects, they should be provided with staff-assisted job search and matching services to obtain suitable and quality job matches with employers seeking qualified workers. The cessation of federal unemployment assistance does not relieve the Department of Labor of its policy responsibility or the responsibility of states under their ES grants to provide statewide employment services to jobless workers seeking new work.

- Food stamps. States need to make sure that workers exhausting jobless benefits are connected to other forms of income support. For example, California’s Employment Development Department has already connected 85,000 Californians to SNAP benefits to help jobless workers and their families put food on the table.41 The end of unemployment benefits could make hundreds of thousands of individuals newly eligible for SNAP benefits—and/or eligible for a higher monthly allotment—due to their sharp drop in income. States should provide clear information to unemployment insurance exhaustees about how to apply for benefits, and wherever possible, should do proactive outreach themselves or with an intermediary organization such as Benefits Data Trust to get individuals started on SNAP applications as soon as possible after their unemployment benefits end (as was done in Pennsylvania in 2012). In addition, states should take full advantage of state flexibility to waive harsh rules that limit unemployed workers classified as Able-Bodied Adults Without Dependents (ABAWDs) to just three months of SNAP benefits in any three-year period.

- Rental assistance. Unemployment benefit recipients are eligible for federal rental assistance, for both back and forward rent for up to eighteen months. State rental assistance programs have been plagued by delays, but the end of unemployment benefits and the expiration of the eviction moratorium have raised the stakes for further improvements. States need to prioritize messaging about rental assistance to unemployment insurance exhaustees, and whenever possible, work with state and regional housing agencies to share information about rental assistance to the unemployment claimant population. Continued regional and state action to prevent evictions through local moratorium or rules that block evictions until rental assistance applications have been processed will be critical to the unemployed population.

- Health care. The American Rescue Plan Act took several steps to make health insurance more accessible during the COVID-19 pandemic, including those unemployed who lost healthy insurance. ARPA broadened eligibility for ACA Marketplace subsidies for individuals who previously did not qualify for subsidized health insurance, as well as enhancing existing subsidies for individuals with lower incomes. In addition, the Biden–Harris administration’s creation of a special enrollment period (SEP) has allowed over one million people to sign up for coverage so far. ARPA created new financial incentives for states to expand Medicaid as well, crucial to closing a coverage gap that disproportionately affects people of color. Some individuals may become newly eligible for Medicaid benefits when their unemployment benefits run out, and causes their family income to drop below the poverty threshold.

Conclusion

While the United States has spent record sums on unemployment benefits, the job is not done. Millions of workers remain out of work, and despite progress, the labor market is nowhere near its pre-COVID19 levels. Cutting off benefits by Labor Day will leave 7.5 million workers without critical assistance they need to keep themselves financially stable until they can find a new job. Imposing such deep hardship on families and the economy, is an unforced economic policy error that can and should be avoided.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Claudia Sahm, Rebecca Vallas, Anna Bernstein, and David Balducchi for contributions, Tom Stengle for continued data assistance, and Samantha Wing for research assistance.

Appendix

Appendix Table 1

| Workers Receiving Federal Unemployment Benefits at Cutoff, by State | ||||

| State | PEUC (Still Unemployed as of September 6) | PUA (Still Unemployed as of September 6) | Total | Can Move on State EB Benefits |

| Alabama | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Alaska | 4,797 | 6,545 | 11,341 | 4,065 |

| Arizona | 17,589 | 55,325 | 72,914 | |

| Arkansas | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| California | 989,229 | 1,069,408 | 2,058,637 | |

| Colorado | 58,035 | 15,971 | 74,006 | |

| Connecticut | 61,081 | 23,340 | 84,422 | 44,366 |

| Delaware | 5,851 | 3,280 | 9,131 | |

| District of Columbia | 2,841 | 9,082 | 11,923 | |

| Florida | 183,110 | 93,813 | 276,923 | |

| Georgia | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Hawaii | 30,816 | 25,815 | 56,631 | |

| Idaho | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Illinois | 235,343 | 110,450 | 345,793 | |

| Indiana | 45,144 | 127,208 | 172,352 | |

| Iowa | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Kansas | 10,957 | 4,888 | 15,846 | |

| Kentucky | 14,822 | 12,575 | 27,397 | |

| Louisiana | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Maine | 15,752 | 7,443 | 23,195 | |

| Maryland | 43,534 | 181,513 | 225,046 | |

| Massachusetts | 138,116 | 175,981 | 314,097 | |

| Michigan | 148,272 | 216,663 | 364,936 | |

| Minnesota | 49,600 | 23,250 | 72,850 | |

| Mississippi | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Missouri | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Montana | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Nebraska | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Nevada | 76,954 | 37,792 | 114,746 | |

| New Hampshire | 0 | 26 | 26 | |

| New Jersey | 133,391 | 259,253 | 392,644 | 105,916 |

| New Mexico | 21,524 | 23,138 | 44,662 | 15,558 |

| New York | 474,402 | 745,548 | 1,219,950 | |

| North Carolina | 77,133 | 55,106 | 132,239 | |

| North Dakota | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Ohio | 80,933 | 189,960 | 270,892 | |

| Oklahoma | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Oregon | 49,044 | 54,075 | 103,120 | |

| Pennsylvania | 179,317 | 311,143 | 490,460 | |

| Puerto Rico | 21,250 | 198,954 | 220,204 | |

| Rhode Island | 13,813 | 24,772 | 38,585 | |

| South Carolina | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| South Dakota | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Tennessee | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Texas | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Utah | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Vermont | 3,643 | 4,931 | 8,574 | |

| Virgin Islands | 486 | 79 | 565 | |

| Virginia | 61,248 | 42,851 | 104,099 | |

| Washington | 50,977 | 71,803 | 122,780 | |

| West Virginia | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Wisconsin | 23,950 | 8,951 | 32,901 | |

| Wyoming | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| US Total | 3,322,956 | 4,190,930 | 7,513,886 | 169,905 |

| Note: States in red have cutoff of all pandemic unemployment benefits. States in purple have cutoff the $300 from FPUC. Source: TCF Analysis of Labor Department Data. |

||||

Notes

- Coronavirus Economic Stabilization (CARES ACT), 15 U.S. Code Ch. 116 (2020), https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?path=/prelim@title15/chapter116&edition=prelim.

- Andrew Stettner, Brian Galle and Elizabeth Pancotti, “Expert Q&A about the Unemployment Provisions of the American Rescue Plan,” The Century Foundation, March 10, 2021, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/questions-answers-unemployment-provisions-america-rescue-plan-act/.

- Aimee Picchi, “Arkansas becomes third state where court blocks cuts to unemployment aid,” CBS News, July 29, 2021, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/arkansas-enhanced-unemployment-benefits-restored-court-ruling/.

- Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, “All Employees, Total Nonfarm,” https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/PAYEMS, accessed August 3, 2021.

- Arkansas is omitted. A lawsuit has prevailed preliminarily but the fate is uncertain.

- “Employment Situation,” Bureau of Labor Statistics, https://www.bls.gov/news.release/empsit.toc.htm, accessed July 29, 2021.

- The Century Foundation, “Unemployment Insurance Data Dashboard,” https://tcf.org/content/data/unemployment-insurance-data-dashboard/, accessed July 29, 2021.

- “Management Report: Preliminary Information on Potential Racial and Ethnic Disparities in the Receipt of Unemployment Insurance Benefits during the COVID-19 Pandemic,” U.S. General Accountability Office, June 17, 2021, https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-21-599r.

- Bill Spriggs, “Black Unemployment Matters Just as Much as White Unemployment,” New York Times, July 19, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/19/opinion/black-unemployment-federal-reserve.html.

- Claire Ewing-Nelson and Jasmine Tucker, “Women Gained 314,000 Jobs in May, But Still Need 13 Straight Months of Growth to Recover Pandemic Losses,” National Women’s Law Center, June 2021, https://nwlc.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/May-Jobs-Day-Final_2.pdf.

- Andrew Stettner and Ellie Kaverman, “State Unilateral Action to Cut Off Federal Benefits: Workers Impacted and Benefits Lost,” The Century Foundation, July 29, 2021, https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1mYzTHhMUOWbW4vBGB0Ia1Vt14mCKSV8aF04ldfsk3HU/edit#gid=174506757.

- “Unemployment Insurance Weekly Claims,” U.S. Department of Labor, https://www.dol.gov/ui/data.pdf, accessed July 29, 2021.

- “Unemployment Insurance Data Dashboard-State Benefit Replacement Rate,” The Century Foundation, http://sautiafrica.org/test/TCF/UIDashboard.html.

- Senator Ron Wyden and Senator Michael Bennet, “Detailed Summary of the Unemployment Insurance Reform Discussion Draft,” Senate Finance Committee, April 14, 2021, https://www.finance.senate.gov/download/long-term-ui-reform-summary.

- Niv Ellis, “Democrats shift tone on unemployment benefits,” The Hill, June 16, 2021, https://thehill.com/policy/finance/558851-democrats-shift-tone-on-unemployment-benefits.

- “Employment Situation,” Bureau of Labor Statistics, https://www.bls.gov/news.release/empsit.toc.htm, accessed July 29, 2021.

- Daniel Perez, Twitter Post, July 2, 2021, https://twitter.com/Dannperr/status/1410973214386315266?s=20.

- “Incentives Not to Work,” Wall Street Journal, April 13, 2010, https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052702303828304575180243952375172.

- “Unemployment Insurance Weekly Claims,” U.S. Department of Labor, December 27, 2012, https://oui.doleta.gov/press/2012/122712.asp.

- “Unemployment Insurance Weekly Claims,” U.S. Department of Labor, December 26, 2002, https://oui.doleta.gov/press/2002/122602.html.

- Nicholas Reimann, “US Chamber Of Commerce Wants End To $300-a-Week Federal Unemployment Benefits—Blames It on Bad Jobs Report,” Forbes, May 7, 2021, https://www.forbes.com/sites/nicholasreimann/2021/05/07/us-chamber-of-commerce-wants-end-to-300-a-week-federal-unemployment-benefits-blames-it-on-bad-jobs-report/.

- “Employment Situation June 2021,” Bureau of Labor Statistics, https://www.bls.gov/news.release/empsit.toc.htm, accessed July 29, 2021.

- Elise Gould, “Economic Indicators: JOLTS,” Economic Policy Institute, July 7, 2021, https://www.epi.org/indicators/jolts/.

- Joseph Altonji et al., “Employment Effects of Unemployment Insurance Generosity During the Pandemic,” Tobin Center for Economic Policy, July 14, 2020, https://tobin.yale.edu/sites/default/files/files/C-19%20Articles/CARES-UI_identification_vF(1).pdf.

- Fiona Greig, Daniel Sullivan, Peter Ganong, Pascal Noel, and Joseph Vavra, “When Unemployment Insurance Benefits are Rolled Back,” J.P. Morgan Institute, July 2021, https://www.jpmorganchase.com/institute/research/household-income-spending/when-unemployment-insurance-benefits-are-rolled-back/.

- Peter Ganong, Twitter Post, July 16, 2021, https://twitter.com/p_ganong/status/1416160296201334786?s=20.

- Aaron Sojourner, Twitter Post, July 27, 2021, https://twitter.com/aaronsojourner/status/1420118208825151499?s=20.

- Howard Schneider, “U.S. states ending federal unemployment benefit saw no clear job gains,” Reuters, July 21, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/world/us/us-states-ending-federal-unemployment-benefit-saw-no-clear-job-gains-2021-07-20/.

- Nicolas Petrosky-Nadeau and Robert G. Valletta, “UI Generosity and Job Acceptance: Effects of the 2020 CARES Act,” Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, Working Paper 2021-13, June 2021, https://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/working-papers/2021/13/.

- Christopher Boone, Arindajit Dube, Lucas Goodman and Ethan Kaplan, “Unemployment Insurance Generosity and Aggregate Employment,” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 13, no. 2 (May 2021), https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/pol.20160613.

- Elise Gould, “Economic Indicators: JOLTS,” Economic Policy Institute, July 7, 2021, https://www.epi.org/indicators/jolts/.

- “It’s a Wage Shortage, Not a Worker Shortage,” One Fair Wage and UC Berkeley Food Labor Research Center, May 2021, https://onefairwage.site/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/OFW_WageShortage_F.pdf.

- “Daily Treasury Statement,” U.S. Department of Treasury, https://fsapps.fiscal.treasury.gov/dts/issues accessed August 2, 2021.

- Mark Zandi, “Using Unemployment Insurance to Help Americans Get Back to Work: Creating Opportunities and Overcoming Challenges,” Testimony to the Senate Finance Committee, April 14, 2010, https://www.economy.com/mark-zandi/documents/Senate-Finance-Committee-Unemployment%20Insurance-041410.pdf.

- “Gross Domestic Product, Second Quarter 2021 (Advance Estimate),” Bureau of Economic Analysis, July 29, 2021, https://www.bea.gov/news/2021/gross-domestic-product-second-quarter-2021-advance-estimate-and-annual-update.

- Jeff Stein, “Delta variant poses major risk to Biden’s promises of swift economic comeback,” Washington Post, July 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/us-policy/2021/07/20/biden-delta-coronavirus-economy/.

- Louis Casiano and Keith Koffer, “Los Angeles County reimposing indoor mask requirement,” Fox News, July 15, 2021, https://www.foxnews.com/politics/los-angeles-county-reimposing-indoor-mask-requirement.

- Andrew Stettner, Rebecca Smith and Rick Mchugh, “Changing Workforce, Changing Economy,” National Employment Law Project, 2004, https://www.nelp.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/ChangingWorkforce.pdf.

- Rachel West, Indivar Dutta-Gupta, Kali Grant, Melissa Boteach, Claire McKenna, and Judy Conti, “Strengthening Unemployment Protections in America,” Center for American Progress, National Employment Law Project, and Georgetown Center on Poverty and Inequality, June 16, 2016, https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/poverty/reports/2016/06/16/138492/strengthening-unemployment-protections-in-america/.

- “Statement by White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki on Biden-Harris Administration Eviction Prevention Efforts,” The White House, July 29, 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/07/29/statement-by-white-house-press-secretary-jen-psaki-on-biden-harris-administration-eviction-prevention-efforts/.

- “Employment Development Department Issues Unemployment Insurance Update, Reminds Californians That Federal Extended Benefit Programs End September 6, 2021,” California Employment Development Department, News Release 21-45, July 30, 2021, https://edd.ca.gov/About_EDD/pdf/news-21-45.pdf.