In the last weeks of 2023, with momentum building in the House for a Pell Grant expansion that would require new funding, lawmakers on the Education and Workforce Committee turned to the student loan program to craft a funding mechanism, known as a “pay-for.” To offset the cost of expanding the Pell Grant so that it could be used for programs less than fifteen weeks in length, the Bipartisan Workforce Pell Act would create a new rule prohibiting institutions with lavish endowments from disbursing federal student loans, effective this year.

Critics of the pay-for have rightly raised alarms that the rule could lead to lower enrollment of low-income students and students of color at highly selective institutions. All the while, another fundamental question has gone under the radar: as a matter of accounting, is this pay-for actually a pay-for?

A closer look suggests that the specific qualities of wealthy institutions’ graduates buck wider trends in the student loan program, altering the conventional math of what would be saved by eliminating student loan access for students at those institutions.

- While the Saving on a Valuable Education (SAVE) plan provides benefits to low- and very-low-income student loan borrowers, some higher-income borrowers in the plan will pay back more than they borrowed, netting positive revenue for the government. Evidence suggests this positive return may disproportionately come from borrowers who attend wealthy, highly selective institutions, many of which are proposed to be cut out of the student loan program.

- Eight years from entry, a typical student from one of the thirty-seven institutions subject to the endowment tax earns nearly double ($77,200) what a typical student from other U.S. institutions earn at the same point in time ($40,200).

- At 77.3 percent of undergraduate programs at endowment tax institutions, the typical borrower is likely to pay more if they enroll in SAVE, as compared to the standard ten-year repayment plan, four years after completion. When comparing SAVE to extended repayment plans, 60.3 percent of graduate-level programs at endowment tax institutions see the typical borrower paying more on SAVE early in their careers.

- If net savings will come from the rule change, the driver will likely be the Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) program. Lawmakers should weigh heavily the implications of the policy change for the public service sector.

As a result, the current pay-for provision may fruitlessly add complexity to the student loan program and set gravely concerning precedents for the future.

Student Loans in the SAVE Paradigm

When lawmakers in Congress considered the budgetary upside of cutting future student loans, the Biden administration’s new student loan repayment plan loomed large. The Saving on a Valuable Education (SAVE) plan, launched in 2023, is the most generous repayment plan in the history of federal student loan programs.

- Under SAVE, a student’s income determines their monthly payment, with more income than ever protected to ensure students need not sacrifice basic needs to pay their monthly student loan bill. Starting in 2024, a student on the SAVE plan can expect to pay only 5 to 10 percent of their discretionary income on their monthly student loan bill.

- If they pay that monthly amount, any remaining interest will be waived, reducing the risk of ever-growing balances.

- After a certain number of years of timely required payments, the remainder of a student’s loan is forgiven, a defense against the threat of a lifetime sentence of student debt.

The benefits of the SAVE plan for borrowers have rightly been touted by the White House and the U.S. Department of Education: for example, the average borrower will find their total payments per dollar drop by 40 percent, and more than a million borrowers per year will qualify for $0 payments under SAVE who would not have qualified under REPAYE, the predecessor to SAVE.

In its evaluation of the Bipartisan Workforce Pell Act’s effects on government spending, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) reports that it expects borrowers to enroll in SAVE, thus increasing the cost of the student loan program. As a result, the CBO expects that the disbursement of student loans would be a net cost to the federal government over the next ten years.

But at the same time, not all borrowers will receive such generous benefits under SAVE. Student loan borrowers who enjoy steady, high incomes may be required to pay more on their monthly bill after opting into SAVE. Some borrowers have expressed disappointment on social media upon finding that their monthly student loan obligation has gone up, as compared to their pre-pandemic amounts: generally, these are borrowers who are economically better today than they were when the student loan repayment pause began in March 2020.

The benefits of SAVE may not ultimately reach a student loan borrower in a high-earning career, except perhaps for a few years early on. Once the borrower has moved into mid-level jobs in a lucrative field, indexing their monthly payment to income will bring their payment above what it would be under the standard repayment plan. When the borrower pays that monthly amount, they pay interest, and thus there is no unpaid interest for the SAVE plan to waive. Assuming there is no lapse in their payment, they will likely finish paying their loan before the SAVE plan’s cancellation benefit would take effect.

The Department of Education’s analysis has found that the borrowers with the highest projected lifetime earnings would see their total payments per dollar borrowed fall only 5 percent compared to the REPAYE plan, versus 83 percent for those at the opposite end of the lifetime earnings spectrum. In the long-run, the federal government likely nets positive revenue on a high-earning borrower’s debt, even if they enroll in SAVE.

If average incomes weren’t any higher for the graduates of one type of institution versus others, then excluding any group of colleges from the student loan program would likely save the federal government money in the long term. However, if there is any category of institutions whose borrowers would have sufficiently high incomes to receive no benefits under SAVE, it’s well-resourced, selective colleges, the same ones Congress proposes to exclude from the student loan program.

The Endowment Tax Institutions

The Bipartisan Workforce Pell Act eliminates future student loan eligibility for institutions subject to an excise tax on investment income for private colleges, first enacted in 2017. The IRS does not publish the list of institutions that pay this tax every year, but an educated guess can be made based on public data. (See Table 1.)

Table 1

| PROJECTED LIST OF INSTITUTIONS SUBJECT TO THE ENDOWMENT TAX AND THEIR ENDOWMENT PER FULL-TIME-EQUIVALENT (FTE) STUDENT |

| Institution |

$ per FTE |

Institution |

$ per FTE |

Institution |

$ per FTE |

| Princeton University |

$4,067,983 |

Wellesley College |

$1,196,665 |

Northwestern University |

$693,590 |

| Yale University |

$2,868,064 |

Dartmouth College |

$1,192,981 |

Bryn Mawr College |

$683,139 |

| Stanford University |

$2,139,952 |

Smith College |

$997,170 |

Duke University |

$673,013 |

| MIT |

$2,090,222 |

Berea College |

$991,921 |

Emory University |

$670,300 |

| Harvard University |

$2,013,622 |

Rice University |

$982,185 |

Davidson College |

$667,026 |

| Amherst College |

$1,685,364 |

Baylor College of Medicine |

$945,133 |

Trinity University |

$646,743 |

| Swarthmore College |

$1,650,659 |

Medical College of Wisconsin |

$934,963 |

Hamilton College |

$622,529 |

| Williams College |

$1,607,993 |

Washington & Lee University |

$894,509 |

Earlham College |

$600,306 |

| Pomona College |

$1,563,312 |

University of Richmond |

$867,110 |

Brown University |

$594,046 |

| Caltech |

$1,516,479 |

University of Pennsylvania |

$839,077 |

Berry College |

$544,101 |

| Grinnell College |

$1,437,742 |

Claremont McKenna |

$805,832 |

Carleton College |

$535,077 |

| University of Notre Dame |

$1,292,237 |

Washington University (St. Louis) |

$794,728 |

|

|

| Bowdoin College |

$1,269,647 |

Vanderbilt University |

$787,384 |

|

|

| Source: Author’s analysis of data from National Association of College and University Business Officers (NACUBO) and Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS). See technical notes for details. |

Together, these thirty-seven institutions awarded $1.5 billion in student loans in the 2022–23 award year, or 1.8 percent of all student loan dollars nationwide that year. Of this $1.5 billion, $119 million are undergraduate loans, $133 million are Parent PLUS loans, and $1.2 billion are graduate loans.

Students who attend these institutions will enjoy lifelong name-brand recognition defined by exclusivity: at the undergraduate level, these institutions had a combined acceptance rate of 8.4 percent in 2022. Graduates of these institutions, perhaps unsurprisingly, report earnings well above the average. Eight years after entry, a typical student from an endowment tax institution earns nearly double ($77,900) what a typical student from other U.S. institutions earns at the same point ($40,200). While endowment tax institutions make up 0.9 percent of all U.S. colleges and universities in the College Scorecard database, they comprise 20 of the top 150 institutions (13.3 percent) by median earnings eight years after entry.

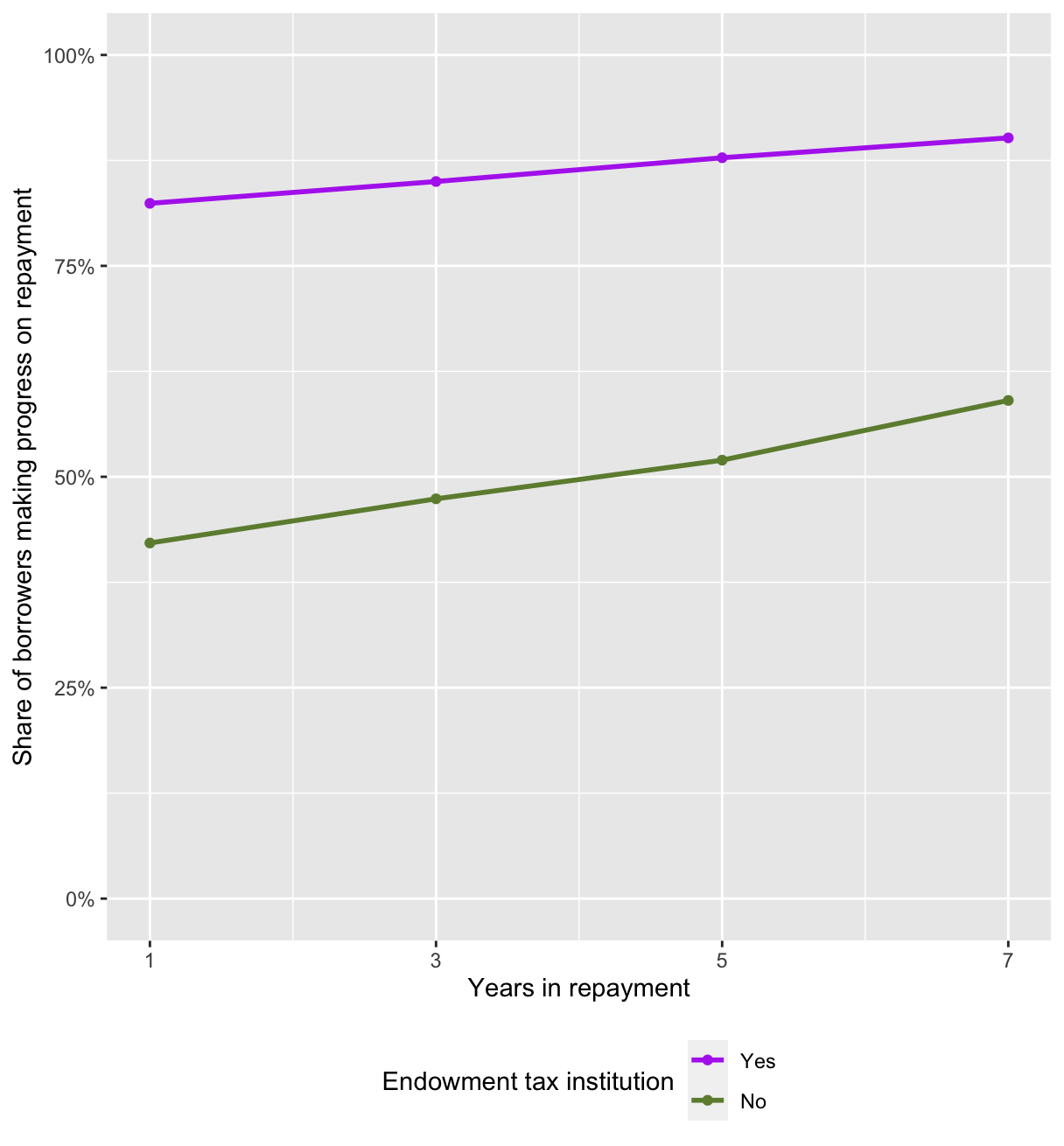

The endowment tax institutions also demonstrate that higher incomes translate to greater success repaying student loans. When examining the share of borrowers who are not in default and whose loan balances have declined since entering repayment, the endowment tax institutions far exceed other U.S. institutions: for example, 85.0 percent of endowment tax institutions’ borrowers make progress paying down their balances three years into repayment, compared to 51.2 percent for borrowers from other institutions. (See Figure 1)

Figure 1: STUDENT LOAN REPAYMENT RATE BY YEARS IN REPAYMENT, ENDOWMENT TAX INSTITUTIONS VERSUS ALL OTHER U.S. INSTITUTIONS

Source: Author’s analysis of data from the College Scorecard. See technical notes for details.

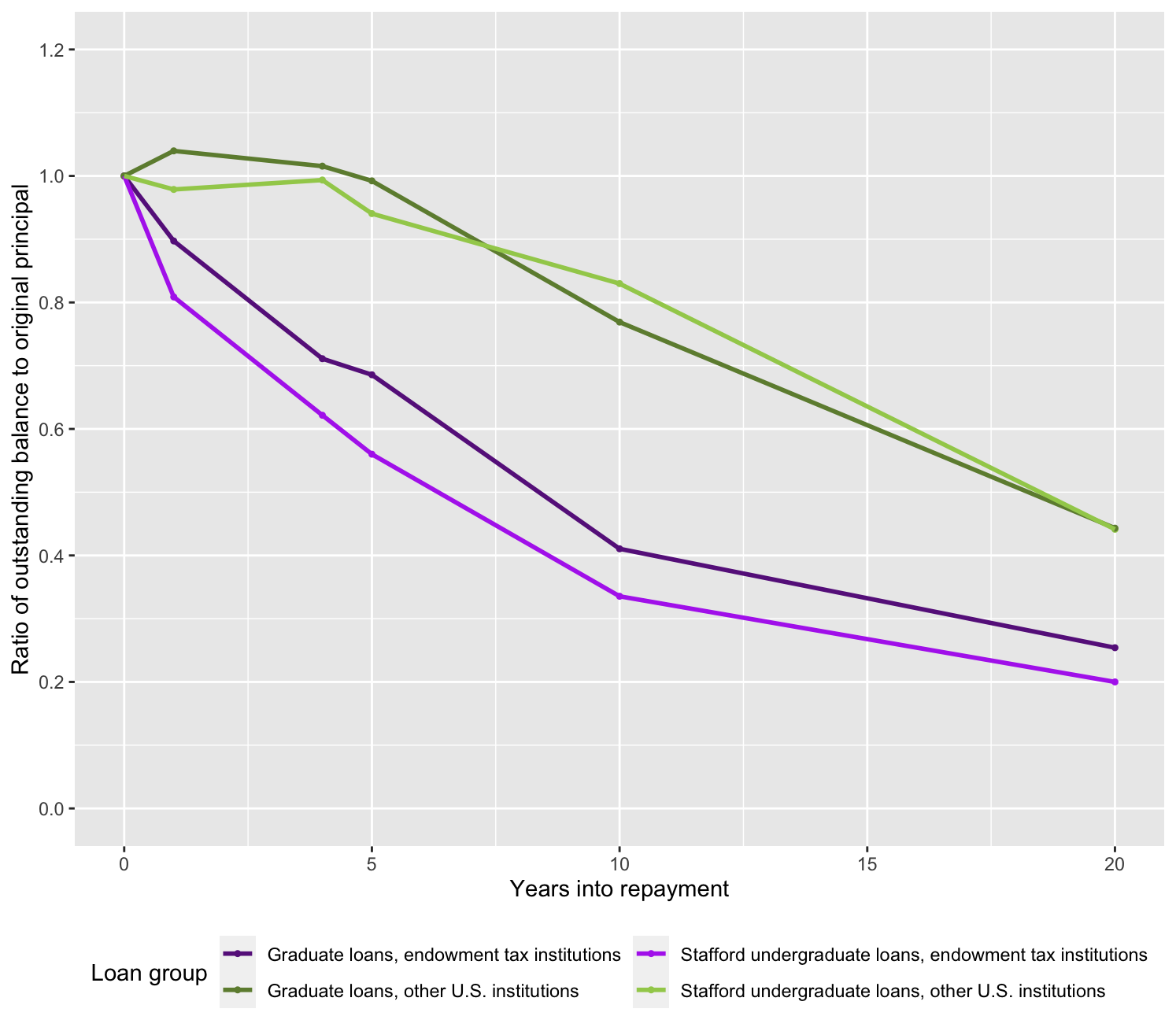

Similarly, borrowers from endowment tax institutions have sizably lower balances relative to their principal several years into repayment, as compared to borrowers from other U.S. institutions. When we measure the balances of borrower cohorts who have been in repayment for five, ten, and twenty years against their original principal, endowment tax institutions consistently show more favorable repayment ratios than other U.S. institutions. (See Figure 2.) For example, ten years into repayment, Stafford undergraduate loan borrowers from endowment tax institutions have only 33 percent of their original balance remaining, versus 83 percent for all other U.S. institutions. The same pattern holds for graduate loan borrowers, by a 41 percent to 77 percent margin.

FIGURE 2: RATIOS OF OUTSTANDING BALANCE TO ORIGINAL PRINCIPAL, ENDOWMENT TAX INSTITUTIONS VERSUS ALL OTHER U.S. INSTITUTIONS.

Source: Author’s analysis of data from the College Scorecard. See technical notes for details.

One exception is Parent PLUS loans: ten years from the start of repayment, there is almost no gap between cohorts of Parent PLUS borrowers whose children attended an endowment tax institution and those whose children attended other U.S. institutions. However, Parent PLUS loans are generally ineligible for income-driven repayment plans, including SAVE, and there are almost no cancellation options available to Parent PLUS borrowers. Because of these restrictions, the government can safely plan to receive more from Parent PLUS loans than it lends, and the Congressional Budget Office estimates that the federal government’s negative subsidy cost (that is, positive net revenue) for Parent PLUS loans is nearly 30 percent.

The Parent PLUS program’s positive net revenue for the government may be one reason the Bipartisan Workforce Pell Act retains endowment tax institutions’ federal student loan eligibility for the parents of dependent undergraduates, but only for those who are not eligible for the Pell Grant. While this would focus the student loan program at endowment tax institutions on the families from which it can expect the most net revenue, the rule change would signal that the federal government is more willing to preserve some lending options for higher-income families but not low-income families, setting a concerning precedent that counters the spirit of equal opportunity in the federal student loan program.

Estimating SAVE Plan Benefits for Student Loan Borrowers at Endowment Tax Institutions

Data on previous cohorts of borrowers show that borrowers from endowment tax institutions are likely to successfully pay down their loan balance, most likely a function of relatively successful career trajectories. However, a key question is whether the introduction of the SAVE plan changes the math so strongly that the net positive revenue these loans previously would provide the government would now become a loss.

While publicly available datasets are not sufficient to project the lifetime payments for every student who borrows a loan from an endowment tax institution, the available data are sufficient to examine a simpler question: several years after their program, would the typical borrower from an endowment tax institution pay less per month under SAVE than if they were on a standard repayment plan? If they do not pay less, that borrower would likely pay full interest regardless of what repayment plan they are on, meaning the government is receiving a positive return on the borrower’s loan, at least at that point in time.

In recent years, the College Scorecard has published detailed data on the earnings of students who received federal student aid, including median earnings of graduates who are working and not enrolled, four years after completing their program. Assuming a family size of one, we can enter this earnings amount into the SAVE plan formula for monthly payments and compare this amount to the median monthly amount under a standard ten-year repayment plan, a data point that is also provided for every program.

Undergraduates

At 77.3 percent of undergraduate programs at endowment tax institutions, the typical borrower is likely to pay more if they enroll in SAVE, as compared to the standard ten-year repayment plan, four years after completing. (See Table 2.) This compares to just 28.5 percent of comparable undergraduate programs at other institutions not subject to the endowment tax.

TABLE 2

|

COUNT OF UNDERGRADUATE PROGRAMS BY GREATER OR LESSER MONTHLY PAYMENT UNDER SAVE

|

|

Early in their careers, would the typical graduate of the program pay more per month under SAVE, or the standard ten-year plan? |

| Pay more under SAVE |

Pay more under standard |

| Undergraduate programs at endowment tax institutions |

194 programs (77.3%) |

57 programs (22.7%) |

| Undergraduate programs at other U.S. institutions |

7,866 programs (28.4%) |

19,746 programs (71.5%) |

| Source: Author’s analysis of data from the College Scorecard. See technical notes for details. |

The typical undergraduate from an endowment tax institution would pay $434 per month on their student loans on SAVE, which is more than double the median monthly payment for these borrowers under a standard repayment plan ($194). By comparison, the typical undergraduate from another U.S. institution would see their monthly payment fall from $249 to $181 under SAVE.

By enrolling in SAVE, the average bachelor’s degree recipient from an endowment tax institution would likely put themselves on track to pay off their loans faster, reducing the likelihood that SAVE would cancel any of their loans. They are also unlikely to see any interest waived under SAVE exceed interest that they pay over the life of their loan. While this analysis only looks at one snapshot in time—earnings four years after completion—it can be assumed that their earnings would only increase thereafter. Similarly, there is no reason to assume that borrowers’ earnings one, two, and three years after completion are vastly lower than earnings four years from completion.

Graduate Students

For all programs, whether undergraduate or graduate level, the College Scorecard reports monthly payments on a standard ten-year plan. However, many graduate loan amounts are quite large, and even successful early-career doctors and lawyers will struggle to repay $150,000 in loans over just ten years. Borrowers with federal student loan principals surpassing $30,000 often opt for extended repayment, which is similar to the standard repayment plan but spans a longer period of time.

After adjusting for borrowers with more than $30,000 in debt likely enrolling in extended repayment plans, the results continue to show a split between programs from endowment tax tax institutions and others. (See Table 3.) Graduates from an estimated 60.3 percent of graduate-level programs at endowment tax institutions may not qualify for SAVE plan benefits due to high incomes, according to this point-in-time analysis. By contrast, the share is 42.3 percent at all other U.S. institutions.

Table 3

|

COUNT OF GRADUATE PROGRAMS BY GREATER OR LESSER MONTHLY PAYMENT UNDER SAVE

|

|

Early in their careers, would the typical graduate of the program pay more per month under SAVE, or a standard/extended repayment plan? |

| Pay more under SAVE |

Pay less under SAVE |

| Graduate programs at endowment tax institutions |

88 programs (60.3%) |

58 programs (39.7%) |

| Graduate programs at other U.S. institutions |

2,714 programs (42.3%) |

3,696 programs (57.7%) |

| Source: Author’s analysis of data from the College Scorecard. See technical notes for details. |

The typical graduate from a graduate-level program at an endowment tax institution would pay $1,088 per month on their student loans on SAVE, which is 49 percent higher than the median monthly payment for these borrowers under a standard or extended repayment plan ($731). By comparison, the typical graduate from a graduate-level program at another U.S. institution would see their monthly payment fall from $520 to $498 under SAVE.

Even with increases to the benefits for borrowers through SAVE, there is some evidence that graduate student loan borrowers from endowment tax institutions are more likely to earn incomes high enough to preclude SAVE plan benefits, and thus are more likely to paying the federal government more money in interest than they would see canceled at the end of their repayment period.

Accounting for Cancelation under SAVE

An important caveat to both the undergraduate and graduate loan analyses presented above is the potential impact of forgiveness under SAVE. For a borrower with a starting balance of $12,000 or less, SAVE will cancel the remaining balance of their loans after ten years of timely minimum payments. As a borrower’s starting balance amount rises, more years of payments are needed before forgiveness takes effect, reaching a cap of twenty years for undergraduate-only borrowers and twenty-five years for others.

In theory, a relatively small number of borrowers could rack up significant forgiveness and have an outsized impact on whether, as a whole, endowment tax institutions’ student loans are a budgetary net-plus or a budgetary net-minus for the federal government. These borrowers would need to have persistently low incomes to qualify for forgiveness, and to the extent there is a minority of very-low-income borrowers from endowment tax institutions, they are not reflected in the median earnings measures used above.

Compared to the median, the twenty-fifth percentile of earnings is a better indicator of the lower tail of earnings: for each institution, it is the value of earnings separating the bottom-quarter from the top three-quarters. The College Scorecard reports the twenty-fifth percentile of earnings for students eight years after they had entered. Those values can be compared to the threshold of 225 percent of the federal poverty guideline, as a reference point for what level of income would trigger $0 payments under SAVE for a single borrower without dependents.

For only three endowment tax institutions (out of thirty-five) does the twenty-fifth percentile of earnings fall below the threshold. (See Table 4.) By contrast, three quarters of the nation’s other institutions see their twenty-fifth percentile of earnings fall below the threshold. In other words, the prevalence of very-low-income borrowers from endowment tax institutions is far lower compared to other U.S. institutions.

Table 4

| COUNT OF INSTITUTIONS BY TWENTY-FIFTH PERCENTILE OF EARNINGS, RELATIVE TO 225 PERCENT OF FPL. |

|

Is a student at the twenty-fifth percentile by earnings under 225 percent of FPL, eight years after entering? (Assuming household of one) |

| Yes |

No |

| Endowment tax institutions |

3 institutions (8.6%) |

32 institutions (91.4%) |

| Other U.S. institutions |

3,032 institutions (75.2%) |

999 institutions (24.8%) |

| Source: Author’s analysis of data from the College Scorecard. See technical notes for details. |

In addition, a graduate who starts off lower-income does not necessarily stay lower-income. According to longitudinal data of 2008 bachelor’s degree earners, one third of graduates from a very selective four-year institution who were in the bottom quartile by income in 2012 had moved out of the bottom quartile by 2018. Moreover, one sixth had moved into the top half by income by 2018.

Together, these findings suggest that relatively few borrowers from endowment tax institutions will likely see large reductions in their monthly payments, and those who do, at any single point in time, are not guaranteed to remain in that low-income range.

No doubt, many student loan borrowers from endowment tax institutions will qualify for cancellation under SAVE, and for some it will amount to a large share of their principal. However, there is reason to think that the interest from other borrowers may still outweigh the sum of canceled loans. If each of four students borrows $10,000 at 6 percent interest and one of them sees the whole balance canceled, never paying a dollar, the lender will still recoup the full value that was lent so long as the other three pay full interest. Even while SAVE relieves the debt burden of the lowest-income borrowers, we have found evidence–at least for endowment tax institutions–that many borrowers will pay interest and not have balances to be canceled by SAVE at the end of the loan period.

Loans Forgiven through PSLF

The other major pathway to cancellation, separate from the SAVE plan, is Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF). Created in 2007, the program cancels remaining balances for Direct Loan borrowers after 120 payments and full-time employment for a qualifying employer over the same period.

Even those who do not enroll in SAVE could see forgiveness through the PSLF program, potentially adding up to a large amount of debt the government would forgive. Eliminating endowment tax institutions’ eligibility to disburse federal student loans would reduce the amount expected to be canceled through PSLF. From survey data, we can learn the following:

- About one-third of bachelor’s earners from very selective institutions worked for a potentially PSLF-eligible employer four years after graduation: 6 percent at the school where they attended, 13 percent at a nonprofit organization, 13 percent at a local, state, or federal agency, and 2 percent in the military.

- Of early Millennials who worked full-time in a potentially PSLF-eligible industry (such as education or health care) any year between 2010 and 2019, one-third worked full-time in a potentially PSLF-eligible industry for all of 2010 to 2019.

- Some evidence also suggests students from endowment tax institutions are less likely than other colleges’ graduates to go into public service. Ivy League institutions’ own surveys of recent graduates’ employment show that, on average, just 21.4 percent of their students go on to work in education, health care, or government, compared to 31.8 percent of all U.S. workers aged 22–25 with bachelor’s degrees. By comparison, the fields of finance, consulting, and technology receive 49.7 percent of recent Ivy League graduates, versus 14.7 percent in the young college-educated workforce.

Together, these findings suggest one out of every nine graduates of selective institutions could be eligible for PSLF, although this may be an overestimate for endowment tax institutions if the trends for Ivy League BA earners hold for the graduates of endowment tax institutions broadly. In the absence of more data, we can only make ballpark estimates.

The Biden administration has made a concerted effort to expand access to the PSLF program. In May 2021, the program had forgiven just $697 million for 9,790 borrowers; two years later, it had forgiven $46.8 billion for 670,264 borrowers, with an average balance of nearly $70,000. Until the dust settles, it is difficult to project now how many new student loans from endowment tax institutions would qualify for PSLF and how sizable the amount would be, given the rapid changes in forgiveness totals.

However, if PSLF is likely to cancel debt for graduates of endowment tax institutions, the cancellation is likely to be concentrated at the graduate level. Most of these institutions’ undergraduate borrowers are likely to see no savings under SAVE, potentially leaving no remaining balance after ten years. By contrast, longer repayment terms for graduate loans leave more to be canceled even after ten years of timely, full payments, but those amounts are difficult to project.

The Drawbacks of Congress’s Proposed Rule, in Dollars and Sense

The CBO estimates that roughly $1.7 billion would be saved over the next decade through the student loan provision of the Bipartisan Workforce Pell Act. The CBO reports that the savings primarily come from graduate student borrowers enrolling in income-driven repayment, which is consistent with the analysis here. However, the CBO’s analysis does not appear to account for the fact that endowment tax institutions are outliers when it comes to earnings after graduation.

The total savings estimated by the CBO potentially overstates the amount of money the federal government “loses” on these loans, and for many loans from endowment tax institutions, the elimination of student loan eligibility will in fact lose the federal government more money than it would save. Meanwhile, the private loan industry would reap profits on loans to many students attending elite universities who would otherwise participate in the federal student loan program.

If net savings do result from the rule change, the driver will likely be forgiveness through PSLF. Based on strong earnings data explored here, endowment tax institutions may be able to communicate the value of enrolling to most prospective students even without the availability of the SAVE plan, but the lack of PSLF eligibility would loom large over students considering a program in education, medicine, or law.

For a service-minded student considering such a program at an endowment tax institution, three outcomes are possible. They may enroll at a similar institution under the endowment tax threshold, not significantly changing the ledger for their student loan. Secondly, they may take their talents to another field of work, which, in the aggregate, hurts already-strained vital workforces of teachers, nurses, and other public sector jobs. Thirdly, if students at endowment tax institutions in public service careers do not change their decisions, the government will save money from their ineligibility for PSLF; however, out of all the graduates of Harvard, Yale, and other endowment tax institutions to be saving money from, the greatest savings would likely come from those sacrificing lucrative careers to serve American communities.

Through the pay-for provision of the Bipartisan Workforce Pell Act, it appears that Congress would create a backward effect of eliminating loans on which it is actually taking in revenue. Worse, the rule change could fruitlessly complicate a financial aid landscape that is already highly complex, and it could set the precedent that every time Congress needs more money for higher education it takes another bite out of the student loan program. The political convenience of the proposed must take a backseat to careful consideration of its long-term ramifications for students and families.

Technical notes on this analysis can be found here.

Tags: federal financial aid, Pell Grants, college affordability

Is Congress’s Pell Pay-For a Pay-For At All?

In the last weeks of 2023, with momentum building in the House for a Pell Grant expansion that would require new funding, lawmakers on the Education and Workforce Committee turned to the student loan program to craft a funding mechanism, known as a “pay-for.” To offset the cost of expanding the Pell Grant so that it could be used for programs less than fifteen weeks in length, the Bipartisan Workforce Pell Act would create a new rule prohibiting institutions with lavish endowments from disbursing federal student loans, effective this year.1

Critics of the pay-for have rightly raised alarms that the rule could lead to lower enrollment of low-income students and students of color at highly selective institutions. All the while, another fundamental question has gone under the radar: as a matter of accounting, is this pay-for actually a pay-for?

A closer look suggests that the specific qualities of wealthy institutions’ graduates buck wider trends in the student loan program, altering the conventional math of what would be saved by eliminating student loan access for students at those institutions.

As a result, the current pay-for provision may fruitlessly add complexity to the student loan program and set gravely concerning precedents for the future.

Student Loans in the SAVE Paradigm

When lawmakers in Congress considered the budgetary upside of cutting future student loans, the Biden administration’s new student loan repayment plan loomed large. The Saving on a Valuable Education (SAVE) plan, launched in 2023, is the most generous repayment plan in the history of federal student loan programs.

The benefits of the SAVE plan for borrowers have rightly been touted by the White House and the U.S. Department of Education: for example, the average borrower will find their total payments per dollar drop by 40 percent, and more than a million borrowers per year will qualify for $0 payments under SAVE who would not have qualified under REPAYE, the predecessor to SAVE.

In its evaluation of the Bipartisan Workforce Pell Act’s effects on government spending, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) reports that it expects borrowers to enroll in SAVE, thus increasing the cost of the student loan program. As a result, the CBO expects that the disbursement of student loans would be a net cost to the federal government over the next ten years.3

But at the same time, not all borrowers will receive such generous benefits under SAVE. Student loan borrowers who enjoy steady, high incomes may be required to pay more on their monthly bill after opting into SAVE. Some borrowers have expressed disappointment on social media upon finding that their monthly student loan obligation has gone up, as compared to their pre-pandemic amounts: generally, these are borrowers who are economically better today4 than they were when the student loan repayment pause began in March 2020.5

The benefits of SAVE may not ultimately reach a student loan borrower in a high-earning career, except perhaps for a few years early on. Once the borrower has moved into mid-level jobs in a lucrative field, indexing their monthly payment to income will bring their payment above what it would be under the standard repayment plan. When the borrower pays that monthly amount, they pay interest, and thus there is no unpaid interest for the SAVE plan to waive.6 Assuming there is no lapse in their payment, they will likely finish paying their loan before the SAVE plan’s cancellation benefit would take effect.

The Department of Education’s analysis has found that the borrowers with the highest projected lifetime earnings would see their total payments per dollar borrowed fall only 5 percent compared to the REPAYE plan, versus 83 percent for those at the opposite end of the lifetime earnings spectrum. In the long-run, the federal government likely nets positive revenue on a high-earning borrower’s debt, even if they enroll in SAVE.

If average incomes weren’t any higher for the graduates of one type of institution versus others, then excluding any group of colleges from the student loan program would likely save the federal government money in the long term. However, if there is any category of institutions whose borrowers would have sufficiently high incomes to receive no benefits under SAVE, it’s well-resourced, selective colleges, the same ones Congress proposes to exclude from the student loan program.

The Endowment Tax Institutions

The Bipartisan Workforce Pell Act eliminates future student loan eligibility for institutions subject to an excise tax on investment income for private colleges, first enacted in 2017.7 The IRS does not publish the list of institutions that pay this tax every year, but an educated guess can be made based on public data. (See Table 1.)

Table 1

Together, these thirty-seven institutions awarded $1.5 billion in student loans in the 2022–23 award year, or 1.8 percent of all student loan dollars nationwide that year. Of this $1.5 billion, $119 million are undergraduate loans, $133 million are Parent PLUS loans, and $1.2 billion are graduate loans.

Students who attend these institutions will enjoy lifelong name-brand recognition defined by exclusivity: at the undergraduate level, these institutions had a combined acceptance rate of 8.4 percent in 2022. Graduates of these institutions, perhaps unsurprisingly, report earnings well above the average. Eight years after entry, a typical student from an endowment tax institution earns nearly double ($77,900) what a typical student from other U.S. institutions earns at the same point ($40,200). While endowment tax institutions make up 0.9 percent of all U.S. colleges and universities in the College Scorecard database, they comprise 20 of the top 150 institutions (13.3 percent) by median earnings eight years after entry.

Sign up for updates.

The endowment tax institutions also demonstrate that higher incomes translate to greater success repaying student loans. When examining the share of borrowers who are not in default and whose loan balances have declined since entering repayment, the endowment tax institutions far exceed other U.S. institutions: for example, 85.0 percent of endowment tax institutions’ borrowers make progress paying down their balances three years into repayment, compared to 51.2 percent for borrowers from other institutions. (See Figure 1)

Figure 1: STUDENT LOAN REPAYMENT RATE BY YEARS IN REPAYMENT, ENDOWMENT TAX INSTITUTIONS VERSUS ALL OTHER U.S. INSTITUTIONS

Source: Author’s analysis of data from the College Scorecard. See technical notes for details.

Similarly, borrowers from endowment tax institutions have sizably lower balances relative to their principal several years into repayment, as compared to borrowers from other U.S. institutions. When we measure the balances of borrower cohorts who have been in repayment for five, ten, and twenty years against their original principal, endowment tax institutions consistently show more favorable repayment ratios than other U.S. institutions. (See Figure 2.) For example, ten years into repayment, Stafford undergraduate loan borrowers from endowment tax institutions have only 33 percent of their original balance remaining, versus 83 percent for all other U.S. institutions. The same pattern holds for graduate loan borrowers, by a 41 percent to 77 percent margin.8

FIGURE 2: RATIOS OF OUTSTANDING BALANCE TO ORIGINAL PRINCIPAL, ENDOWMENT TAX INSTITUTIONS VERSUS ALL OTHER U.S. INSTITUTIONS.

Source: Author’s analysis of data from the College Scorecard. See technical notes for details.

One exception is Parent PLUS loans: ten years from the start of repayment, there is almost no gap between cohorts of Parent PLUS borrowers whose children attended an endowment tax institution and those whose children attended other U.S. institutions. However, Parent PLUS loans are generally ineligible for income-driven repayment plans, including SAVE, and there are almost no cancellation options available to Parent PLUS borrowers. Because of these restrictions, the government can safely plan to receive more from Parent PLUS loans than it lends, and the Congressional Budget Office estimates that the federal government’s negative subsidy cost (that is, positive net revenue) for Parent PLUS loans is nearly 30 percent.

The Parent PLUS program’s positive net revenue for the government may be one reason the Bipartisan Workforce Pell Act retains endowment tax institutions’ federal student loan eligibility for the parents of dependent undergraduates, but only for those who are not eligible for the Pell Grant. While this would focus the student loan program at endowment tax institutions on the families from which it can expect the most net revenue, the rule change would signal that the federal government is more willing to preserve some lending options for higher-income families but not low-income families, setting a concerning precedent that counters the spirit of equal opportunity in the federal student loan program.

Estimating SAVE Plan Benefits for Student Loan Borrowers at Endowment Tax Institutions

Data on previous cohorts of borrowers show that borrowers from endowment tax institutions are likely to successfully pay down their loan balance, most likely a function of relatively successful career trajectories. However, a key question is whether the introduction of the SAVE plan changes the math so strongly that the net positive revenue these loans previously would provide the government would now become a loss.

While publicly available datasets are not sufficient to project the lifetime payments for every student who borrows a loan from an endowment tax institution, the available data are sufficient to examine a simpler question: several years after their program, would the typical borrower from an endowment tax institution pay less per month under SAVE than if they were on a standard repayment plan? If they do not pay less, that borrower would likely pay full interest regardless of what repayment plan they are on, meaning the government is receiving a positive return on the borrower’s loan, at least at that point in time.

In recent years, the College Scorecard has published detailed data on the earnings of students who received federal student aid, including median earnings of graduates who are working and not enrolled, four years after completing their program. Assuming a family size of one,9 we can enter this earnings amount into the SAVE plan formula for monthly payments and compare this amount to the median monthly amount under a standard ten-year repayment plan, a data point that is also provided for every program.

Undergraduates

At 77.3 percent of undergraduate programs at endowment tax institutions, the typical borrower is likely to pay more if they enroll in SAVE, as compared to the standard ten-year repayment plan, four years after completing. (See Table 2.) This compares to just 28.5 percent of comparable undergraduate programs at other institutions not subject to the endowment tax.

TABLE 2

COUNT OF UNDERGRADUATE PROGRAMS BY GREATER OR LESSER MONTHLY PAYMENT UNDER SAVE

The typical undergraduate from an endowment tax institution would pay $434 per month on their student loans on SAVE, which is more than double the median monthly payment for these borrowers under a standard repayment plan ($194). By comparison, the typical undergraduate from another U.S. institution would see their monthly payment fall from $249 to $181 under SAVE.

By enrolling in SAVE, the average bachelor’s degree recipient from an endowment tax institution would likely put themselves on track to pay off their loans faster, reducing the likelihood that SAVE would cancel any of their loans. They are also unlikely to see any interest waived under SAVE exceed interest that they pay over the life of their loan. While this analysis only looks at one snapshot in time—earnings four years after completion—it can be assumed that their earnings would only increase thereafter.10 Similarly, there is no reason to assume that borrowers’ earnings one, two, and three years after completion are vastly lower than earnings four years from completion.

Graduate Students

For all programs, whether undergraduate or graduate level, the College Scorecard reports monthly payments on a standard ten-year plan. However, many graduate loan amounts are quite large, and even successful early-career doctors and lawyers will struggle to repay $150,000 in loans over just ten years. Borrowers with federal student loan principals surpassing $30,000 often opt for extended repayment, which is similar to the standard repayment plan but spans a longer period of time.

After adjusting for borrowers with more than $30,000 in debt likely enrolling in extended repayment plans, the results continue to show a split between programs from endowment tax tax institutions and others.11 (See Table 3.) Graduates from an estimated 60.3 percent of graduate-level programs at endowment tax institutions may not qualify for SAVE plan benefits due to high incomes, according to this point-in-time analysis. By contrast, the share is 42.3 percent at all other U.S. institutions.

Table 3

COUNT OF GRADUATE PROGRAMS BY GREATER OR LESSER MONTHLY PAYMENT UNDER SAVE

The typical graduate from a graduate-level program at an endowment tax institution would pay $1,088 per month on their student loans on SAVE, which is 49 percent higher than the median monthly payment for these borrowers under a standard or extended repayment plan ($731). By comparison, the typical graduate from a graduate-level program at another U.S. institution would see their monthly payment fall from $520 to $498 under SAVE.

Even with increases to the benefits for borrowers through SAVE, there is some evidence that graduate student loan borrowers from endowment tax institutions are more likely to earn incomes high enough to preclude SAVE plan benefits, and thus are more likely to paying the federal government more money in interest than they would see canceled at the end of their repayment period.

Accounting for Cancelation under SAVE

An important caveat to both the undergraduate and graduate loan analyses presented above is the potential impact of forgiveness under SAVE. For a borrower with a starting balance of $12,000 or less, SAVE will cancel the remaining balance of their loans after ten years of timely minimum payments. As a borrower’s starting balance amount rises, more years of payments are needed before forgiveness takes effect, reaching a cap of twenty years for undergraduate-only borrowers and twenty-five years for others.

In theory, a relatively small number of borrowers could rack up significant forgiveness and have an outsized impact on whether, as a whole, endowment tax institutions’ student loans are a budgetary net-plus or a budgetary net-minus for the federal government. These borrowers would need to have persistently low incomes to qualify for forgiveness, and to the extent there is a minority of very-low-income borrowers from endowment tax institutions, they are not reflected in the median earnings measures used above.

Compared to the median, the twenty-fifth percentile of earnings is a better indicator of the lower tail of earnings: for each institution, it is the value of earnings separating the bottom-quarter from the top three-quarters. The College Scorecard reports the twenty-fifth percentile of earnings for students eight years after they had entered. Those values can be compared to the threshold of 225 percent of the federal poverty guideline, as a reference point for what level of income would trigger $0 payments under SAVE for a single borrower without dependents.12

For only three endowment tax institutions (out of thirty-five) does the twenty-fifth percentile of earnings fall below the threshold. (See Table 4.) By contrast, three quarters of the nation’s other institutions see their twenty-fifth percentile of earnings fall below the threshold. In other words, the prevalence of very-low-income borrowers from endowment tax institutions is far lower compared to other U.S. institutions.

Table 4

In addition, a graduate who starts off lower-income does not necessarily stay lower-income. According to longitudinal data of 2008 bachelor’s degree earners, one third of graduates from a very selective four-year institution who were in the bottom quartile by income in 2012 had moved out of the bottom quartile by 2018. Moreover, one sixth had moved into the top half by income by 2018.

Together, these findings suggest that relatively few borrowers from endowment tax institutions will likely see large reductions in their monthly payments, and those who do, at any single point in time, are not guaranteed to remain in that low-income range.

No doubt, many student loan borrowers from endowment tax institutions will qualify for cancellation under SAVE, and for some it will amount to a large share of their principal. However, there is reason to think that the interest from other borrowers may still outweigh the sum of canceled loans. If each of four students borrows $10,000 at 6 percent interest and one of them sees the whole balance canceled, never paying a dollar, the lender will still recoup the full value that was lent so long as the other three pay full interest.13 Even while SAVE relieves the debt burden of the lowest-income borrowers, we have found evidence–at least for endowment tax institutions–that many borrowers will pay interest and not have balances to be canceled by SAVE at the end of the loan period.

Loans Forgiven through PSLF

The other major pathway to cancellation, separate from the SAVE plan, is Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF).14 Created in 2007, the program cancels remaining balances for Direct Loan borrowers after 120 payments and full-time employment for a qualifying employer over the same period.

Even those who do not enroll in SAVE could see forgiveness through the PSLF program, potentially adding up to a large amount of debt the government would forgive. Eliminating endowment tax institutions’ eligibility to disburse federal student loans would reduce the amount expected to be canceled through PSLF. From survey data, we can learn the following:

Together, these findings suggest one out of every nine graduates of selective institutions could be eligible for PSLF, although this may be an overestimate for endowment tax institutions if the trends for Ivy League BA earners hold for the graduates of endowment tax institutions broadly. In the absence of more data, we can only make ballpark estimates.

The Biden administration has made a concerted effort to expand access to the PSLF program. In May 2021, the program had forgiven just $697 million for 9,790 borrowers; two years later, it had forgiven $46.8 billion for 670,264 borrowers, with an average balance of nearly $70,000. Until the dust settles, it is difficult to project now how many new student loans from endowment tax institutions would qualify for PSLF and how sizable the amount would be, given the rapid changes in forgiveness totals.

However, if PSLF is likely to cancel debt for graduates of endowment tax institutions, the cancellation is likely to be concentrated at the graduate level.15 Most of these institutions’ undergraduate borrowers are likely to see no savings under SAVE, potentially leaving no remaining balance after ten years. By contrast, longer repayment terms for graduate loans leave more to be canceled even after ten years of timely, full payments, but those amounts are difficult to project.

The Drawbacks of Congress’s Proposed Rule, in Dollars and Sense

The CBO estimates that roughly $1.7 billion would be saved over the next decade through the student loan provision of the Bipartisan Workforce Pell Act. The CBO reports that the savings primarily come from graduate student borrowers enrolling in income-driven repayment, which is consistent with the analysis here. However, the CBO’s analysis does not appear to account for the fact that endowment tax institutions are outliers when it comes to earnings after graduation.16

The total savings estimated by the CBO potentially overstates the amount of money the federal government “loses” on these loans, and for many loans from endowment tax institutions, the elimination of student loan eligibility will in fact lose the federal government more money than it would save. Meanwhile, the private loan industry would reap profits on loans to many students attending elite universities who would otherwise participate in the federal student loan program.

If net savings do result from the rule change, the driver will likely be forgiveness through PSLF. Based on strong earnings data explored here, endowment tax institutions may be able to communicate the value of enrolling to most prospective students even without the availability of the SAVE plan, but the lack of PSLF eligibility would loom large over students considering a program in education, medicine, or law.

For a service-minded student considering such a program at an endowment tax institution, three outcomes are possible. They may enroll at a similar institution under the endowment tax threshold, not significantly changing the ledger for their student loan. Secondly, they may take their talents to another field of work, which, in the aggregate, hurts already-strained vital workforces of teachers, nurses, and other public sector jobs. Thirdly, if students at endowment tax institutions in public service careers do not change their decisions, the government will save money from their ineligibility for PSLF; however, out of all the graduates of Harvard, Yale, and other endowment tax institutions to be saving money from, the greatest savings would likely come from those sacrificing lucrative careers to serve American communities.

Through the pay-for provision of the Bipartisan Workforce Pell Act, it appears that Congress would create a backward effect of eliminating loans on which it is actually taking in revenue. Worse, the rule change could fruitlessly complicate a financial aid landscape that is already highly complex, and it could set the precedent that every time Congress needs more money for higher education it takes another bite out of the student loan program. The political convenience of the proposed must take a backseat to careful consideration of its long-term ramifications for students and families.

Technical notes on this analysis can be found here.

Notes

Tags: federal financial aid, Pell Grants, college affordability