Luzia has been singing her whole life. She began writing music at the age of 8, when she lived in Angola. Looking back, she describes her first songs as “silly.” Now, after just two years in Maine, Luzia has begun performing in major competitions and events across the country, including in Washington, D.C. as part of a multinational girls chorus group.

“By singing [in English at school], I get to learn new vocabulary words, and [I found] a place to feel seen.”

Chorus has been hugely influential in Luzia’s experience in schools here. It’s allowed her to strengthen her voice, see the country, learn English, and find belonging. To this point, she told me, “I had a talent coming in [to the United States], but I didn’t speak English yet. By singing [in English at school], I get to learn new vocabulary words, and [I found] a place to feel seen.”

Westbrook Schools: “The Best Education For All—For Life”

Luzia moved to the United States two years ago. First, she enrolled in the Freeport School District, just north of Portland. She didn’t speak any English, and she was nervous and scared, but she remembers office staff helping her get clothes and supplies for school. There weren’t that many multilingual learners (MLs) in her school, but she found a teacher who spoke Portuguese, her native language, and a small clique of Angolan peers for the 2022–23 school year.

The next year, her family found more affordable housing in Westbrook—west of downtown Portland—and she enrolled in ninth grade at Westbrook High School for the 2023–24 school year. She immediately encountered nice teachers and several other immigrant students learning English. She says she was nervous starting all over again, but her incipient community made her feel “safe and comfortable.”

Westbrook Public Schools has the third-largest ML population of any Maine school district, falling just behind Portland and Lewiston. Indeed, as of September 2024, 22 percent of its student population consists of students classified as MLs. What’s more, Westbrook’s ML population has doubled since 2017. And its dedication to these newcomers does justice to the district’s motto: “The Best Education For All—For Life.”

Fortunately, Westbrook has not experienced the same loss and/or shortage of certified English for Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL) teachers to match its growing ML population in the past few years that other districts have felt. Instead, the district has retained its teaching workforce and been able to hire additional ML teachers as the number of identified MLs has grown, employing twenty ML teachers and six paraprofessionals this 2024–25 school year. Altogether, Westbrook has been able to establish about a 25:1 ML student-to-certified teacher ratio.

At Westbrook High School, one in five students are MLs. This marks a significant shift from its beginnings: it remains the only high school in the district, but when it opened in the 1950s, it was a community school serving an almost completely white student body. Seven decades later, Westbrook’s students speak eighteen different languages—the most common are Arabic, Portuguese, Spanish, and French—and represent twenty-seven birth countries. The majority, however, come from Angola, Iraq, and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

This is what makes Westbrook special. Indeed, a teacher reflected on why he came to Westbrook High when considering his different employment options within the Portland metro area: “[The ability to] work with immigrant multilingual learners is what brings us to Westbrook. [It’s a] great opportunity and a gift.”

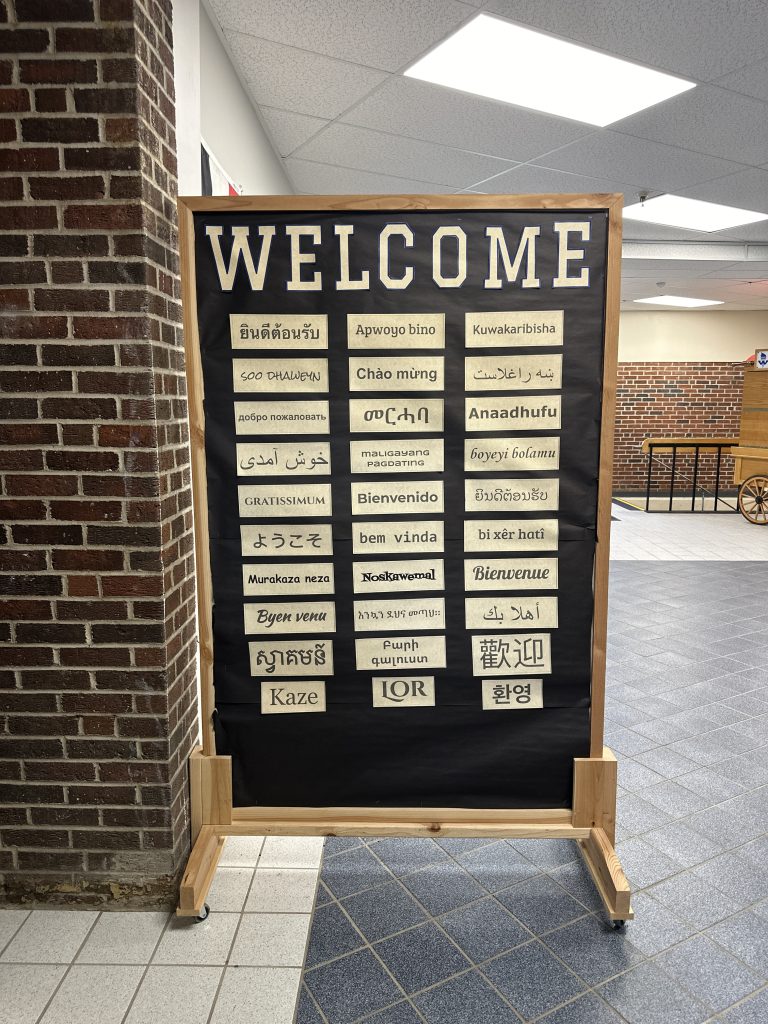

CAPTION: A multilingual board welcomes students and families at the entrance of Westbrook High School. Credit: Alejandra Vázquez Baur

The rich diversity of the Westbrook community is palpable to visitors from their first step into the building. A big board positioned at the entrance welcomes students and families in thirty languages. All school signage—from bathroom signposts, class rules, and even the “trash and recycling here” notes—is translated into French, Spanish, Portuguese, and Arabic. The library is stocked with books in these languages as well. Colorful posters for Arabic School, Spanish and Portuguese Club, and the Student Civil Rights Collective decorate the hallway walls. “Halal School Meals” reads one sign, reminding students that halal food options are available and emphasizing the importance of halal school meal accommodations for Muslim students. These signs and others underscore the intention to cultivate a school community where students can trust that their cultures are welcome and respected.

“All Hands on Deck” with Westbrook’s Newcomers

When I visited the district this fall, I spoke with several teachers at Westbrook High who work with newcomers. Each mentioned significant programmatic support from school and district leadership in serving their students. For instance, the district provides “sheltered newcomer” classes, where newly arrived students with gaps in education and low English proficiency can receive more of their instruction within content-based courses separate from their non-newcomer peers as they continue to gain their English proficiency. Ms. Bethany Magdziarz uses this model in her Algebra I class, where a paraprofessional works with students with significant gaps in math instruction while she builds vocabulary and content knowledge with the rest of the class. All students in the class have arrived within the past year. Ms. Magdziarz has been at Westbrook for several years and is known as the “newcomer math” teacher. Mr. Haider Almukhtar, a paraprofessional from Iraq, has worked with Westbrook’s newcomers for over a decade.

For students who have gained sufficient English language proficiency in the sheltered classes, Westbrook recently launched a co-teaching model to ensure newcomers receive the support they need while they transition and integrate into mainstream core content classes with non-ML peers. One example I observed is a co-taught English III class. Mr. Caleb Taylor is the subject lead, and he has taught high school English for nine years. Ms. Amanda Martemucci-MacDonald has been teaching for twelve years and is certified to differentiate English and Literature instruction for multilingual learners. They collaborate in planning lessons that center diverse perspectives and are relevant to students’ interests and backgrounds.

While the co-teaching model is new for Westbrook, it creates more opportunities for MLs to develop English proficiency in classes with their peers. This might be contributing to the school’s successful language assessment scores. Last year, 70 percent of their identified MLs demonstrated measurable growth in their overall English proficiency—which measures speaking, listening, reading, and writing—and six students met the state’s exit criteria for the ML identification.

I have visited many schools in which the teachers and social workers care deeply about their newcomers, but where there is little or no support for this population and their needs from leadership. The support from the school’s administration sets Westbrook apart. Three co-principals lead the school. While Principal Patrick Colgan manages MLs and the Seal of Biliteracy program, all three recognize that newcomers are not a monolithic group, and their needs can only be met when they collaborate across their lanes. As Principal Cari Shardella described it, they have lanes to ease decision-making, but ultimately it’s an “all hands on deck” mentality that gets things done.

School leadership’s collaboration helps bolster translation and interpretation services, establish key community organization partnerships, and connect families to critical physical, dental, and mental health supports in culturally responsive and sustaining ways, regardless of citizenship status.

Their collaboration helps bolster translation and interpretation services, establish key community organization partnerships, and connect families to critical physical, dental, and mental health supports in culturally responsive and sustaining ways, regardless of citizenship status. One notable example is ShifaME, which provides counseling for children and families in the district who have experienced trauma or severe stress associated with being a refugee, asylee, or immigrant.

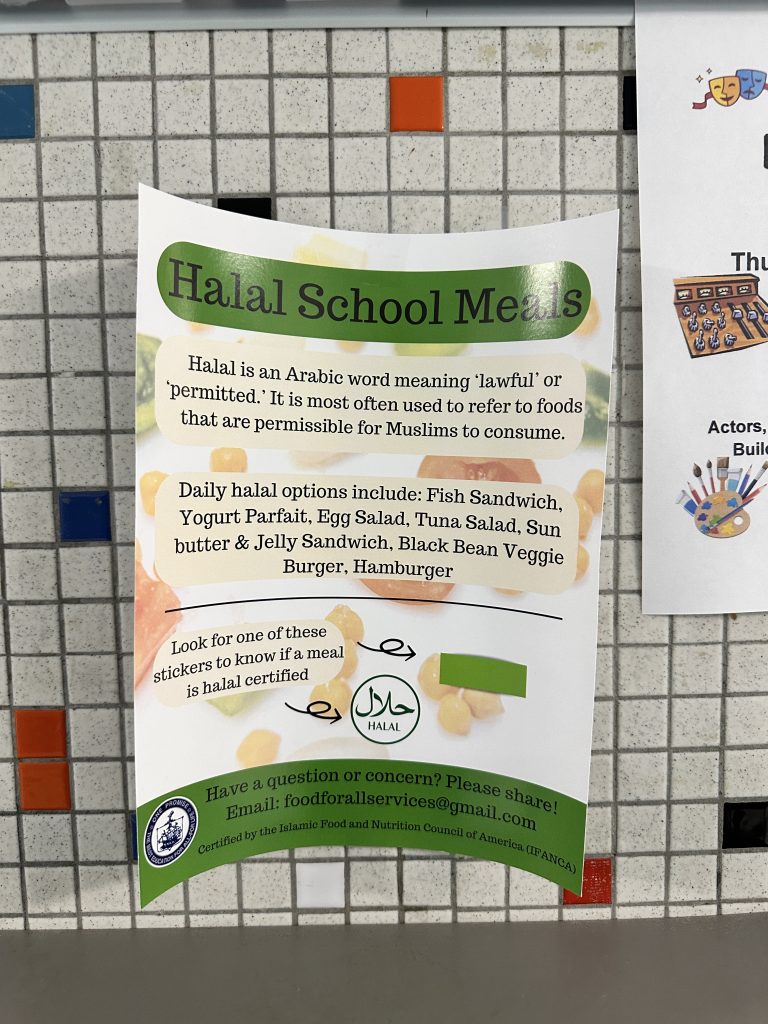

CAPTION: A sign at Westbrook High School describing halal-certified cafeteria options. Credit: Alejandra Vázquez Baur

Westbrook’s principals also mention the importance of supporting MLs in more informal ways. For example, family engagement and school-based activities take into account the many cultures represented at the school. Every year, students proudly wear traditional dress during Spirit Week. During Eid, the school community comes together to break fast with Muslim families. Over the years, a student-led Iftar dinner has grown from a small, eight-student affair to a school-supported event that serves over eighty people. The principals say that small efforts to build community-led cultural programming reduce ethnic-related conflicts in the school, and it has led to students sharing more about themselves with their peers and building more empathy throughout the community.

Critically, school leaders said that community partnerships and resources are relatively cheap and mutually beneficial. Students and families get what they need in an affordable and culturally and linguistically appropriate way, and these organizations gain direct access to hundreds of families who might not otherwise find them if not through the schools. Reflecting on the costs and benefits of these community investments, Principal Wendy Harvey said, “[These programs] can’t be add-ons. It has to be a core value of the school and community. Therefore, we have to re-organize what we have to meet the needs of our communities.”

Immigrants in Maine

According to the 2023 American Community Survey, 94 percent of Maine’s 1.4 million people speak only English at home, and 92 percent are white. Moreover, this predominantly white and English-speaking state’s population is also the oldest of any U.S. state, with a median age of 45.1. Until recently, Maine hasn’t seen particularly significant demographic changes, and isn’t often considered a “destination state” for newly arrived immigrants.

Despite this, Maine’s immigrant and refugee populations have grown over the years. The population of foreign-born people in Maine—lovingly referred to as “New Mainers”—has grown 53.8 percent between 2000 and 2022, now making up 4.1 percent of the total population. This growth is prevalent in Maine’s schools, as well. Multilingual learners made up 4.2 percent of Maine’s student population in the 2023–24 school year, nearly mirroring the state proportion of foreign-born Mainers and demonstrating 15-percent growth from the previous school year. Notably, 61 percent of Maine’s MLs in that same school year were Black, making Maine home to one of the highest concentrations of MLs who are Black. These demographic shifts in Maine’s population over the last two decades have necessitated similar shifts in services and resources to support them across the state.

Charles Mugabe, director of migration at Maine Catholic Charities, has seen these shifts in his work. As the non-governmental organization in charge of administering the U.S. Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR)’s Maine programs (its replacement designee), it has long worked on the federal government’s behalf to support refugees in the state. However, as the asylee population has grown, the organization expanded its purview to include asylum seekers in all of their programming, including workforce placement and resettlement services for families in temporary housing or shelters. This has required new funding sources, tailored programming, and strong partnerships with community-based organizations and multiple agencies, including local districts like Westbrook. Luckily, New Mainers have a few allies in the Maine Department of Education (DOE).

Maine Education Department Invests in Immigrant and Refugee Stories

Driven by harmful and xenophobic rhetoric about immigrants during the 2016 presidential campaign, Portland resident Kirsten Cappy began collecting children’s and young adult books about the richness of the immigrant community. Shortly thereafter, she co-founded I’m Your Neighbor Books, a Maine-based non-profit organization that collects books that represent modern, non-European migrants and their new generations in order to diversify school and national dialogues that have predominantly centered early-twentieth-century European migration.

At first, she built relationships with Catholic Charities and Mano en Mano to distribute heritage-language books to children in those programs, to help bridge their arrival and the English schooling process. Then, the Maine Attorney General’s Office student civil rights group selected four I’m Your Neighbor books for their “books of the year” efforts, getting Kirsten and her team’s mission noticed by Maine government officials. Now, after several years cultivating a diverse collection of books in multiple languages, Kirsten and her team have secured a critical partnership with the Maine DOE.

In early September, the Maine DOE and I’m Your Neighbor Books unveiled the Welcoming Library: Pine Collection, a thoughtfully curated set of picture books shipped to each school administrative unit (SAU) across the state of Maine that reflect the diverse experiences of immigrant families and their children. Each book includes discussion questions to help educators facilitate impactful classroom conversations that grow students’ academic, social, and emotional skills and encourage racial literacy.

In addition, educators in every Maine SAU have access to Pine Professional Learning Modules: free professional development in which educators are prompted to reflect on and connect with their teaching practices, helping them create supportive and inclusive learning environments for all their students, especially refugees and immigrant-origin students.

Because of the state’s relatively small population size, an effort like this is easier to pilot. The Maine DOE used ESSER funds to develop and implement the modules, something they were able to do because of the wide flexibility provided to use those funds to support students most impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly students from marginalized groups.

When the program launched, Associate Commissioner of Public Education Megan Welter said, “As Maine welcomes more immigrant and New American families, it’s incredibly important that students see themselves and their families represented in the books in their school libraries. These books also encourage all students to create a welcoming environment and appreciate the incredible diversity in our communities and nation.”

As Welter’s statement indicates, while the project is designed to benefit New Mainers foremost, its potential impact on broader Maine is perhaps more important. By expanding this effort to every SAU in the state, Maine education leaders expose non-immigrant, U.S.-born students to the rich stories of their immigrant peers. Importantly, this offers all Mainers an opportunity to develop empathy for communities with experiences different from their own. Melanie Junkins, Pine Project lead from the Maine DOE, said that this is where the hard work of equity really takes place.

A Student Gives Back

Two months into her second year at Westbrook High School, Luzia is busy. Thanks to the robust programming available to her at school, she’s thriving in her classes, learning to write poetry, rehearsing with the girls chorus group, and preparing for basketball season. She says she feels more confident this year, and she’s excited to serve as an ambassador for newly arrived MLs.

I asked her what she plans to say to new students when they first show up. She said she’ll repeat what her favorite teacher, Ms. Kelly Fernald, told her on her first day at Westbrook: “Don’t worry about anything. Everyone is supportive here. You’ll learn English, you’ll get to meet people, and [you’ll] become really comfortable.” She’s more than comfortable now: she’s a leader among her peers, and now that she’s found the nest she needed as an artist, she’s ready to spread her wings and take the country by storm.

Tags: English Language Learners, newcomer, national newcomer network, multilingualism

How Maine Schools are Welcoming “New Mainers”

Luzia1 has been singing her whole life. She began writing music at the age of 8, when she lived in Angola. Looking back, she describes her first songs as “silly.” Now, after just two years in Maine, Luzia has begun performing in major competitions and events across the country, including in Washington, D.C. as part of a multinational girls chorus group.

Chorus has been hugely influential in Luzia’s experience in schools here. It’s allowed her to strengthen her voice, see the country, learn English, and find belonging. To this point, she told me, “I had a talent coming in [to the United States], but I didn’t speak English yet. By singing [in English at school], I get to learn new vocabulary words, and [I found] a place to feel seen.”

Westbrook Schools: “The Best Education For All—For Life”

Luzia moved to the United States two years ago. First, she enrolled in the Freeport School District, just north of Portland. She didn’t speak any English, and she was nervous and scared, but she remembers office staff helping her get clothes and supplies for school. There weren’t that many multilingual learners (MLs) in her school, but she found a teacher who spoke Portuguese, her native language, and a small clique of Angolan peers for the 2022–23 school year.

The next year, her family found more affordable housing in Westbrook—west of downtown Portland—and she enrolled in ninth grade at Westbrook High School for the 2023–24 school year. She immediately encountered nice teachers and several other immigrant students learning English. She says she was nervous starting all over again, but her incipient community made her feel “safe and comfortable.”

Westbrook Public Schools has the third-largest ML population of any Maine school district,2 falling just behind Portland and Lewiston. Indeed, as of September 2024, 22 percent of its student population consists of students classified as MLs. What’s more, Westbrook’s ML population has doubled since 2017. And its dedication to these newcomers does justice to the district’s motto: “The Best Education For All—For Life.”

Fortunately, Westbrook has not experienced the same loss and/or shortage of certified English for Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL) teachers to match its growing ML population in the past few years that other districts have felt. Instead, the district has retained its teaching workforce and been able to hire additional ML teachers as the number of identified MLs has grown, employing twenty ML teachers and six paraprofessionals this 2024–25 school year. Altogether, Westbrook has been able to establish about a 25:1 ML student-to-certified teacher ratio.

At Westbrook High School, one in five students are MLs. This marks a significant shift from its beginnings: it remains the only high school in the district, but when it opened in the 1950s, it was a community school serving an almost completely white student body. Seven decades later, Westbrook’s students speak eighteen different languages—the most common are Arabic, Portuguese, Spanish, and French—and represent twenty-seven birth countries. The majority, however, come from Angola, Iraq, and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

This is what makes Westbrook special. Indeed, a teacher reflected on why he came to Westbrook High when considering his different employment options within the Portland metro area: “[The ability to] work with immigrant multilingual learners is what brings us to Westbrook. [It’s a] great opportunity and a gift.”

CAPTION: A multilingual board welcomes students and families at the entrance of Westbrook High School. Credit: Alejandra Vázquez Baur

The rich diversity of the Westbrook community is palpable to visitors from their first step into the building. A big board positioned at the entrance welcomes students and families in thirty languages. All school signage—from bathroom signposts, class rules, and even the “trash and recycling here” notes—is translated into French, Spanish, Portuguese, and Arabic. The library is stocked with books in these languages as well. Colorful posters for Arabic School, Spanish and Portuguese Club, and the Student Civil Rights Collective decorate the hallway walls. “Halal School Meals” reads one sign, reminding students that halal food options are available and emphasizing the importance of halal school meal accommodations for Muslim students. These signs and others underscore the intention to cultivate a school community where students can trust that their cultures are welcome and respected.

“All Hands on Deck” with Westbrook’s Newcomers

When I visited the district this fall, I spoke with several teachers at Westbrook High who work with newcomers. Each mentioned significant programmatic support from school and district leadership in serving their students. For instance, the district provides “sheltered newcomer” classes, where newly arrived students with gaps in education and low English proficiency can receive more of their instruction within content-based courses separate from their non-newcomer peers as they continue to gain their English proficiency. Ms. Bethany Magdziarz uses this model in her Algebra I class, where a paraprofessional works with students with significant gaps in math instruction while she builds vocabulary and content knowledge with the rest of the class. All students in the class have arrived within the past year. Ms. Magdziarz has been at Westbrook for several years and is known as the “newcomer math” teacher. Mr. Haider Almukhtar, a paraprofessional from Iraq, has worked with Westbrook’s newcomers for over a decade.

For students who have gained sufficient English language proficiency in the sheltered classes, Westbrook recently launched a co-teaching model to ensure newcomers receive the support they need while they transition and integrate into mainstream core content classes with non-ML peers. One example I observed is a co-taught English III class. Mr. Caleb Taylor is the subject lead, and he has taught high school English for nine years. Ms. Amanda Martemucci-MacDonald has been teaching for twelve years and is certified to differentiate English and Literature instruction for multilingual learners. They collaborate in planning lessons that center diverse perspectives and are relevant to students’ interests and backgrounds.

While the co-teaching model is new for Westbrook, it creates more opportunities for MLs to develop English proficiency in classes with their peers. This might be contributing to the school’s successful language assessment scores. Last year, 70 percent of their identified MLs demonstrated measurable growth in their overall English proficiency—which measures speaking, listening, reading, and writing—and six students met the state’s exit criteria for the ML identification.

I have visited many schools in which the teachers and social workers care deeply about their newcomers, but where there is little or no support for this population and their needs from leadership. The support from the school’s administration sets Westbrook apart. Three co-principals lead the school. While Principal Patrick Colgan manages MLs and the Seal of Biliteracy program, all three recognize that newcomers are not a monolithic group, and their needs can only be met when they collaborate across their lanes. As Principal Cari Shardella described it, they have lanes to ease decision-making, but ultimately it’s an “all hands on deck” mentality that gets things done.

Their collaboration helps bolster translation and interpretation services, establish key community organization partnerships, and connect families to critical physical, dental, and mental health supports in culturally responsive and sustaining ways, regardless of citizenship status. One notable example is ShifaME, which provides counseling for children and families in the district who have experienced trauma or severe stress associated with being a refugee, asylee, or immigrant.

CAPTION: A sign at Westbrook High School describing halal-certified cafeteria options. Credit: Alejandra Vázquez Baur

Westbrook’s principals also mention the importance of supporting MLs in more informal ways. For example, family engagement and school-based activities take into account the many cultures represented at the school. Every year, students proudly wear traditional dress during Spirit Week. During Eid, the school community comes together to break fast with Muslim families. Over the years, a student-led Iftar dinner has grown from a small, eight-student affair to a school-supported event that serves over eighty people. The principals say that small efforts to build community-led cultural programming reduce ethnic-related conflicts in the school, and it has led to students sharing more about themselves with their peers and building more empathy throughout the community.

Critically, school leaders said that community partnerships and resources are relatively cheap and mutually beneficial. Students and families get what they need in an affordable and culturally and linguistically appropriate way, and these organizations gain direct access to hundreds of families who might not otherwise find them if not through the schools. Reflecting on the costs and benefits of these community investments, Principal Wendy Harvey said, “[These programs] can’t be add-ons. It has to be a core value of the school and community. Therefore, we have to re-organize what we have to meet the needs of our communities.”

Immigrants in Maine

According to the 2023 American Community Survey, 94 percent of Maine’s 1.4 million people speak only English at home, and 92 percent are white. Moreover, this predominantly white and English-speaking state’s population is also the oldest of any U.S. state, with a median age of 45.1. Until recently, Maine hasn’t seen particularly significant demographic changes, and isn’t often considered a “destination state” for newly arrived immigrants.

Despite this, Maine’s immigrant and refugee populations have grown over the years. The population of foreign-born people in Maine—lovingly referred to as “New Mainers”—has grown 53.8 percent between 2000 and 2022, now making up 4.1 percent of the total population. This growth is prevalent in Maine’s schools, as well. Multilingual learners made up 4.2 percent of Maine’s student population in the 2023–24 school year, nearly mirroring the state proportion of foreign-born Mainers and demonstrating 15-percent growth from the previous school year. Notably, 61 percent of Maine’s MLs in that same school year were Black, making Maine home to one of the highest concentrations of MLs who are Black. These demographic shifts in Maine’s population over the last two decades have necessitated similar shifts in services and resources to support them across the state.

Charles Mugabe, director of migration at Maine Catholic Charities, has seen these shifts in his work. As the non-governmental organization in charge of administering the U.S. Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR)’s Maine programs (its replacement designee), it has long worked on the federal government’s behalf to support refugees in the state. However, as the asylee population has grown, the organization expanded its purview to include asylum seekers in all of their programming, including workforce placement and resettlement services for families in temporary housing or shelters. This has required new funding sources, tailored programming, and strong partnerships with community-based organizations and multiple agencies, including local districts like Westbrook. Luckily, New Mainers have a few allies in the Maine Department of Education (DOE).

Maine Education Department Invests in Immigrant and Refugee Stories

Driven by harmful and xenophobic rhetoric about immigrants during the 2016 presidential campaign, Portland resident Kirsten Cappy began collecting children’s and young adult books about the richness of the immigrant community. Shortly thereafter, she co-founded I’m Your Neighbor Books, a Maine-based non-profit organization that collects books that represent modern, non-European migrants and their new generations in order to diversify school and national dialogues that have predominantly centered early-twentieth-century European migration.

At first, she built relationships with Catholic Charities and Mano en Mano to distribute heritage-language books to children in those programs, to help bridge their arrival and the English schooling process. Then, the Maine Attorney General’s Office student civil rights group selected four I’m Your Neighbor books for their “books of the year” efforts, getting Kirsten and her team’s mission noticed by Maine government officials. Now, after several years cultivating a diverse collection of books in multiple languages, Kirsten and her team have secured a critical partnership with the Maine DOE.

In early September, the Maine DOE and I’m Your Neighbor Books unveiled the Welcoming Library: Pine Collection, a thoughtfully curated set of picture books shipped to each school administrative unit (SAU) across the state of Maine that reflect the diverse experiences of immigrant families and their children. Each book includes discussion questions to help educators facilitate impactful classroom conversations that grow students’ academic, social, and emotional skills and encourage racial literacy.

In addition, educators in every Maine SAU have access to Pine Professional Learning Modules: free professional development in which educators are prompted to reflect on and connect with their teaching practices, helping them create supportive and inclusive learning environments for all their students, especially refugees and immigrant-origin students.

Because of the state’s relatively small population size, an effort like this is easier to pilot. The Maine DOE used ESSER funds to develop and implement the modules, something they were able to do because of the wide flexibility provided to use those funds to support students most impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly students from marginalized groups.

When the program launched, Associate Commissioner of Public Education Megan Welter said, “As Maine welcomes more immigrant and New American families, it’s incredibly important that students see themselves and their families represented in the books in their school libraries. These books also encourage all students to create a welcoming environment and appreciate the incredible diversity in our communities and nation.”

As Welter’s statement indicates, while the project is designed to benefit New Mainers foremost, its potential impact on broader Maine is perhaps more important. By expanding this effort to every SAU in the state, Maine education leaders expose non-immigrant, U.S.-born students to the rich stories of their immigrant peers. Importantly, this offers all Mainers an opportunity to develop empathy for communities with experiences different from their own. Melanie Junkins, Pine Project lead from the Maine DOE, said that this is where the hard work of equity really takes place.

A Student Gives Back

Two months into her second year at Westbrook High School, Luzia is busy. Thanks to the robust programming available to her at school, she’s thriving in her classes, learning to write poetry, rehearsing with the girls chorus group, and preparing for basketball season. She says she feels more confident this year, and she’s excited to serve as an ambassador for newly arrived MLs.

I asked her what she plans to say to new students when they first show up. She said she’ll repeat what her favorite teacher, Ms. Kelly Fernald, told her on her first day at Westbrook: “Don’t worry about anything. Everyone is supportive here. You’ll learn English, you’ll get to meet people, and [you’ll] become really comfortable.” She’s more than comfortable now: she’s a leader among her peers, and now that she’s found the nest she needed as an artist, she’s ready to spread her wings and take the country by storm.

Notes

Tags: English Language Learners, newcomer, national newcomer network, multilingualism