The United Nations Security Council is expected to decide this week on whether to renew its legal mandate for Syria’s cross-border humanitarian response. The Security Council vote has the potential to remake the life-saving humanitarian architecture that has been built around the country’s years-long civil war.

The Security Council’s decision may also—despite efforts by backers of renewal to cast it as a purely humanitarian measure—have real political significance. Since 2014, the Security Council has sanctioned cross-border aid without the consent of the Syrian regime of Bashar al-Assad, a powerful symbol of Syria’s disintegration and broken sovereignty. The re-centering of the international humanitarian response in Damascus would be another step towards restoring the Assad regime’s international legitimacy and effective political control.

If the Security Council ends this humanitarian framework, it will be another symbolic victory for the Assad regime. But it will also complicate and endanger the humanitarian aid that millions of Syrians rely on—and with which the regime is likely to interfere if it can reassert its hold on aid delivery. It was the regime’s intransigence and abuse that originally prompted the United Nations to suspend the normal rules of state sovereignty. Now, with no real improvement in its conduct, the regime is poised to claw back control over aid to populations it considers hostiles and enemies of the state.

Humanitarians are just hoping to continue providing aid to millions inside Syria, and to keep their own principles mostly intact.

“We’re afraid of getting sucked into a political and diplomatic conversation we have very little control of, and being forced to pronounce ourselves in favor of non-humanitarian compromises,” one humanitarian source told me. 1 Like more than a dozen other humanitarians and donor-country diplomats, he spoke to me on condition of anonymity because of the sensitivity of the upcoming vote and so as not to threaten his organization’s continued work.

Since July 2014, United Nations Security Council resolution 2165 and its various successor resolutions have enabled the delivery of assistance to millions in areas unreachable from Damascus. UNSCR 2165’s mandate has allowed UN agencies to provide assistance themselves and to play a key coordinating role in the broader response, as well as lending international legitimacy to cross-border work by local and international non-governmental organizations (NGOs). But 2165 has only been renewed in year-long installments, and the current mandate expires on January 10. A Security Council vote to renew the resolution is, as of this writing, expected to be held on Tuesday, December 19.

Renewal essentially depends on the vote of permanent member of the Security Council and Assad-regime ally Russia, and no one has a really reliable sense of what Russia wants. In advance of the vote, Russia has taken a critical line on renewal, complaining about aid diversion and the measure’s violation of Syrian sovereignty. “This mechanism cannot be maintained in its current form,” Russia’s UN envoy said last month.2

Most expect that 2165 will be renewed—this time. But even an extension is likely to be only a temporary reprieve, sources told me: a conditional renewal for six months or a year before the resolution is allowed to expire totally. And no one knows for sure. It remains possible that Russia will just veto a renewal outright, leaving humanitarians scrambling to reorganize the response before January 11.

The humanitarians and donors involved in the cross-border response are swimming against a current that runs, inexorably, towards Damascus.

Either way, the humanitarians and donors involved in the cross-border response are swimming against a current that runs, inexorably, towards Damascus. For millions of Syrians caught in that vortex, cross-border assistance provided under UNSCR 2165 has been, in the words of a top UN relief official, a “lifeline.”3

“These [relief] organizations will be going, at some point, back to the origin,” a humanitarian told me. “Cross-border will die. What concerns me is the way it will die.”4

The Genesis of the UN Cross-Border Response

The Security Council passed UNSCR 2165 in July 2014. The resolution was an expression of international frustration with the Assad regime’s obstruction of aid to besieged and other insurgent-held areas. It came after an earlier resolution aimed at opening up humanitarian access had been ignored.5

The original Security Council resolution authorized UN agencies and their implementing partners to provide cross-border assistance “with notification to the Syrian authorities”—not advance permission from Damascus.6 It permitted the use of four official border crossings, “in addition to those already in use.” That latter clause arguably legitimated the use of unofficial border points such as Fish Khabour, the sole operational crossing to Syria’s northeast.7 The resolution also mandated the creation of a monitoring mechanism for cross-border UN assistance.

UNSCR 2165 also allowed notification-only cross-line assistance—that is, across conflict lines from regime-held areas to opposition-held areas—but no aid agencies ultimately acted on that permission.

UN agencies have used the 2165 mandate to deliver cross-border assistance from Jordan, Turkey, and Iraq to sections of Syria that have fallen out of central state control. Under the UN mechanism, UN-supported humanitarian cargoes are inspected and sealed before crossing into the country, and some NGOs also use the UN’s cross-border logistics capacity. UN agencies have also partnered with local Syrian and international NGOs to provide cross-border aid, funding them through sub-grants. And the UN has played a key leadership and coordination role in the broader cross-border response, establishing a “Whole of Syria” architecture and a set of “clusters” to coordinate relief actors.

UN-supplied aid is only a fraction of the cross-border aid response. Cross-border aid predated UNSCR 2165, and it also includes humanitarian assistance from NGOs, relief from Gulf charities, and Western-funded “stabilization” assistance for civil society, basic services, and governance. Much of this is sustained remotely through cash transfers, or enters Syria as commercial cargo and is not checked by the UN monitoring mechanism.

But UN assistance is nonetheless vital. According to the UN Secretary-General’s most recent reporting, in October the UN delivered food aid to more than 797,700 people via cross-border convoys.8 This is in addition to other UN assistance and the systemic impact of the UN’s coordination role on the broader cross-border relief effort, which supports millions. Cross-border beneficiaries were reached consistently—not intermittently, as with cross-line assistance from Damascus. According to the most recent Security Council briefing by UN humanitarian chief Mark Lowcock, on average, just over a quarter of beneficiaries included in bi-monthly access plans actually received cross-line aid, as the government declined to allow UN convoys to proceed.9 Lowcock said in an October briefing that, on average, only 10 percent of people in besieged opposition-held areas were reached with UN assistance each month this year. Key items, including medical supplies, are regularly removed from aid convoys.10

“Our experience with cross-line operations from within Syria,” Lowcock said in October, “leads us to believe that it would be impossible to reach those people in a sustained manner from within Syria.”

“The renewal of the resolution is essential to save lives,” he reiterated last month.

The nonrenewal of UNSCR 2165 would put a halt to UN cross-border assistance and have a larger systemic impact on the cross-border response, including on the international legitimacy and acceptability of cross-border aid generally.

Security Council Maneuvering

Humanitarians told me that as late as this summer, no one was worried about the renewal of UNSCR 2165. By this fall, though, it had become a major concern and a preoccupation of humanitarians and donors—albeit a quiet one.

There has been a conscious collective effort to avoid bringing too much public attention to 2165, even as, privately, it has been the talk of the aid community.11 Backers of renewal have mostly avoided activist-y letters or public statements, and instead relied on closed-door meetings and advocacy in New York.

“We’re trying to keep a lid on this,” one humanitarian told me. “By upping the attention, we give Russia leverage we don’t want them to have.”12

Humanitarians have even avoided creating formal contingency plans, the existence of which might signal their readiness to yield on “technical rollover”—un-amended, year-long renewal. “Plan A is a technical rollover,” said the same humanitarian, speaking last month. “Our line is that there is no Plan B.”13

The Security Council’s three permanent Western members—the United States, Britain, and France, the “P3”—favor technical rollover, as do many non-permanent members. The Syrian government, unsurprisingly, is against it. The Syrians claim that most cross-border assistance ends up in the hands of “terrorist groups” and that these crossings are used to arm militants.14

But the swing vote, the only one that really matters, is Russia. Last December, Russia voted for the passage of UNSCR 2332, the latest renewal of 2165. But that vote came after a bruising fight in the Security Council over Aleppo, whose rebel-held eastern neighborhoods were collapsing,15 and Russia might have had its fill of international reprobation. In 2017, Russia just repeatedly vetoed attempts to renew the internationally sanctioned mechanism to investigate chemical weapons attacks in Syria—a sign that Moscow may be done caring about global outrage.16

Russia has signaled, in public and private, that it wants to see the end of UNSCR, at least as it currently exists. In a statement at the Security Council last month, Russia’s UN envoy Vassily Nebenzia made public complaints that Russia had already made privately about aid diversion and insufficient monitoring of cross-border assistance. He said that, thanks to talks sponsored by Russia in Kazakhstan’s capital Astana, the volume of cross-line convoys has increased. In addition, he stressed, 2165 violates Syrian sovereignty. The resolution “is an unprecedented and extreme measure that must now be reassessed,” Nebenzia said.17

Humanitarians are emphatic that “de-escalation” agreements, including those concluded in Astana, have not improved cross-line access. “The paradox is that cross-line access doesn’t really exist, and now we’re talking about stopping cross-border,” one told me.18 They also stress the robustness of the UN monitoring mechanism, on the border and at delivery points.

What exactly Russia wants in exchange for renewing 2165 is unclear. They have floated some amendments and trades in private, including discussion of a new monitoring mechanism. But if the mechanism concentrates on the border, it would seem set up to fail; it wouldn’t capture most non-UN NGO assistance, much of which is based on cash transfers into Syria and local procurement of goods.

Or Russia may just want to close out UNSCR 2165 and move forward. On December 11, Russian president Vladimir Putin visited Syria’s Hmeimim Airbase to declare victory in the fight over the Islamic State and order a partial withdrawal of Russian forces from Syria.19 Russia is trying to turn the international focus to Syria’s political process and post-war reconstruction. The expiration of 2165 would be a major symbolic step towards the international re-legitimization of the Assad regime and normalcy.

The Russian mission to the UN did not respond to a request for comment prior to publication.

Donor governments and humanitarians are working for UNSCR 2165’s renewal, but it’s not clear how they can affect Russia’s thinking. Even if Russia appears to negotiate, both sides may just be working towards a position Russia has already decided in advance.

As of this writing, the pro-renewal camp has deliberately avoided politicizing the debate over 2165. “We see this as a purely humanitarian mechanism that gets aid to the people who need it the quickest, and closest, and most effective way,” said one Western diplomat. “It’s not a political thing, from our perspective.”

“When the Council discusses this issue, it should be on the basis that it is a purely humanitarian tool,” he said.20

The most likely scenario at the time of this writing seems to be renewal of six months to a year with what could be considered a “sunset clause”—for example, a requirement that the UN Secretary-General report on how to improve the assistance monitoring mechanism, which would lay the groundwork for either a substantial revision of 2165 or its end. After this abbreviated renewal period, Russia could decline to renew again.

“I don’t believe it’s not going to be renewed. It would be too much of a headache for everyone,” said one humanitarian. “I think Russia is quite aware right now that cross-border intervention is serving their interests, although it threatens the territorial integrity of the Syrian government.

“They can live with it for a couple months,” she said. “But I don’t think it will be renewed past the summer.”21

Russia evidently wants UNSCR 2165 to conclude, but an alternative humanitarian mechanism doesn’t yet exist. The humanitarian community is unprepared for an abrupt end to 2165. Six or nine more months, though, might get them partway there.

“If 2165 is extended a couple months,” the same humanitarian told me, “that could give people a big kick in the ass to work out an alternative way to do operations.”22

After UNSCR 2165

Still, there are limits to how much relief agencies can adapt to the end of internationally sanctioned cross-border access.

The worst scenario is that UNSCR 2165 is abruptly vetoed this week and aid organizations are caught flat-footed. In that case, a humanitarian told me, “Plan B is not a plan—just a Titanic moment, where we have to distribute life vests. And I guess the UN will be the orchestra. Just keep playing.”23

But the termination of 2165 seems inevitable, either now or next year. Meanwhile, the reasons why the cross-border aid effort exists—and why a newly Damascus-centric response would be disastrous—will not change.

The Damascus relief hub does not have the capacity to compensate for the cross-border response, humanitarians told me. The main obstacle is access—specifically, the impenetrable Syrian government bureaucracy that humanitarians must navigate to secure permissions for cross-line aid convoys. This multi-layer authorization process has not been meaningfully reformed or relaxed, and no humanitarians I spoke to expected it to improve.

When the regime does okay cross-line convoys, it removes key items, caps relief quantities, and rounds down UN population estimates. Thus, even the limited numbers of successful relief convoys can be deceiving. “Access has become the metric of the success of the response,” said the same humanitarian, saying that just because convoy goes in doesn’t mean it’s delivered what’s most needed. “The convoy is counted as ‘reached.’ It’s a volumetric extrapolation.”24

A secondary obstacle is that many rebel-held areas are resistant to receiving aid via Damascus, which they see as having political strings attached. They are unfriendly in particular to the Syrian Arab Red Crescent, which is regarded as a political actor.

The cross-border and the cross-line response are complementary. “We’re trying to push the message that both [cross-border and cross-line] should continue,” said another humanitarian. “The worst-case scenario is that the resolution is not renewed, but there also isn’t more access from Damascus. It would be a disaster for this population.”25

“For us, cross-border is not preferred,” said another. “But we’re concerned about the lack of any other viable mechanism.”26

While nonrenewal of UNSCR 2165 would not be good, its precise impact is unclear. The ramifications for the UN seem mostly known. UN agencies will likely be obliged to base out of Damascus and halt cross-border activities. But for the broader cross-border response, there are a number of variables at work, including the respective reactions of NGOs, donors, and neighboring countries. How much will each of these parties be willing to flout Syrian sovereignty and law, particularly when the Syrian regime-state is making a comeback?

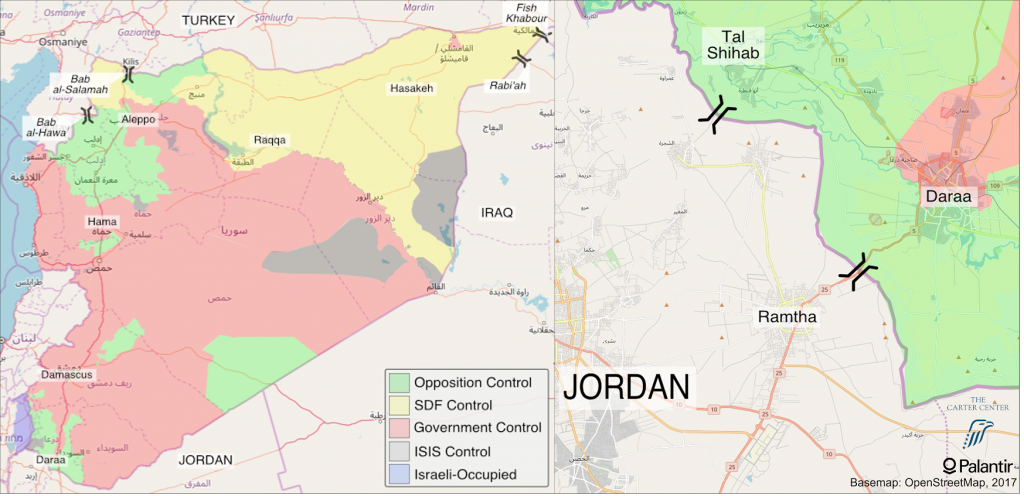

For example, the unofficial Tal Shihab crossing on Syria’s southern border with Jordan “is being used by [international NGOs] thanks to, let’s say, a flexible approach by the Jordanians,” said one humanitarian. “That’s a liberty that’s been agreed to by the Jordanians. The question is how much the Jordanians would like to maintain that unofficial border crossing and put themselves in what would probably be a confrontational stance with the Syrians.

“We’re not in 2013, 2014 anymore, when everyone was betting on Bashar’s regime falling down.”27

Many donor countries seem likely to continue their support for cross-border humanitarian assistance. And local and international NGOs could continue working, although they will likely be hit by the loss of UN funding for cross-border programming. Some organizations use the UN mechanisms at the official crossings and lack permissions to send relief through unofficial crossings, which will likely be strained by additional use. And without international legal legitimacy, these NGOs will be vulnerable. Their cross-border activities are illegal under Syrian law, so, for legal cover, they will depend on the goodwill of Syria’s neighbors and their appetite for violating Syrian sovereignty.

Both Turkey and Jordan seem to have recognized that the project of regime change in Syria, in which they participated, has failed. The two countries would both prefer cross-border aid to continue to avoid destabilizing these border areas and setting off new refugee flows, and Turkey has now occupied and taken more direct ownership of sections of Aleppo and Idlib. But Turkey, at least, has already cracked down on relief NGOs,28 and Jordan’s position on the Assad regime is ambiguous.29 If reduced cross-border access drove NGOs to, for example, rely more heavily on informal cash transfers to local partners and inside-Syria procurement of supplies, that might be enough to make either country nervous about money changing hands unaccountably and push them to run out more relief organizations. Their staff might be in danger of arrest or deportation.

The unofficial Fish Khabour crossing with Iraq poses its own challenges. It is the main artery of support for Syria’s northeast, which is now controlled by America’s local Kurdish partners in the military campaign against the Islamic State. Because Turkey has closed its border—it considers that Kurdish force a grave terrorist threat—relief and stabilization assistance runs through Fish Khabour. If the end of 2165 imperils NGOs’ ability to send in staff and supplies, that could in turn undermine U.S.-led post-Islamic State stabilization efforts.

The United States might have to make a special diplomatic effort to keep Fish Khabour open and to ensure that whatever Iraqi force is manning the crossing’s other side keeps traffic running. The Assad regime specifically objects to the use of Fish Khabour. In an October letter to the UN Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council, Syrian UN envoy Bashar al-Jaafari claimed that Fish Khabour is not covered by UNSCR 2165 and said its use violates Syrian sovereignty. Yet his letter omitted the “in addition to those already in use” clause that has been used to justify aid through Fish Khabour.30 The crossing figures into Syrian objections both to foreign occupation of Syrian territory and international support for allegedly separatist, non-state governance structures.

But all these reverberations will seemingly shake the relief effort regardless of Tuesday’s vote. UNSCR 2165 cannot last forever. The normal international order does not accommodate this sort of exceptional humanitarian measure. Eventually, the millions of Syrians in areas outside regime control will suffer—although, with luck, not yet.

“If we thought this was something durable, we were wrong,” a humanitarian told me. “It was always temporary.”31

Humanitarian Aid and Political Power

Relief organizations are already reorienting towards Damascus, humanitarians told me, and applying for registration to work under the Assad regime. They want to serve needy Syrians where they are; by now, most are living in areas of regime control.

But the regime has not somehow gotten more magnanimous or accommodating as its fortunes have improved. “The Syrian government has been getting more arrogant with NGOs,” said one humanitarian. “They say, if you want to operate from Damascus, you need to accept A, B, C, and D. Are we ready to accept?”32

“I doubt they’ll forgive, and I doubt they’ll forget. You will be marked,” another told me, discussing NGOs that had operated cross-border from Syria’s neighbors and that actually manage to register in Damascus.

“So you’ll have a tier of NGOs who have been in Damascus, and will get preferential treatment for access, and a tier in Damascus who will basically be procurement agencies for [the Syrian Arab Red Crescent],” he said. “Life will be fucking miserable, they’ll make them pay.”33

This return to Damascus will only further subvert humanitarians’ sacrosanct principles of humanity, neutrality, impartiality, and independence. For years, it has been debatable whether the Syrian aid response was “principled.” Some humanitarians maintain that when NGOs split between one cohort in Damascus and another operating cross-border from Syria’s neighbors and, arguably, chose sides in the country’s war, neutrality and impartiality were finished. But operating from Damascus under a revanchist Assad regime will mean a new level of compromise.

“Ultimately, what [Damascus wants] to achieve is total control of humanitarian action,” a humanitarian told me. “The principle of impartiality, they don’t know about that. They want to be sure assistance is delivered as a peace dividend, not based on needs.”34

The shift of the international humanitarian effort to Damascus is a reflection of the regime’s mounting strength and centrality, but it is also, in real terms, an integral part of that power dynamic.

The shift of the international humanitarian effort to Damascus is a reflection of the regime’s mounting strength and centrality, but it is also, in real terms, an integral part of that power dynamic. Humanitarians are not observers to the Syrian war, they are participants.

“We should be careful considering the Syrian government the final winner,” said another humanitarian. “If we think this is the future, the final outcome, we’re probably empowering this government.

“There needs to be some reflection,” he continued. “Are we changing history with our actions? We’re probably not the biggest actor, but there are repercussions to what NGOs do.”35

In a country in which assistance is now a major part of the economy, aid flows mean economic and political power. A post-2165 Syria with a single relief hub in Damascus—as opposed to several, including ones in Gaziantep, Amman, and Deirik—is a Syria with a single center of political gravity, towards which all the country’s restive peripheral regions will find themselves drawn. The end of UNSCR 2165 and the reordering of the humanitarian response is another step towards the return of Syria as a single, integral country ruled by the regime from Damascus.

UNSCR 2165 was a suspension of the normal rules of an international system premised on state sovereignty and legitimacy. It couldn’t last.

That system broke down in Syria as the state and country fell apart. Now the regime-led Syrian state is reconstituting itself, and the walls of that system are being rebuilt around it. Inside, Syrians will be trapped.

Cover Photo: CHILDREN IN A MAKESHIFT SCHOOL IN DARA’A PROVINCE. SOURCE: UNICEF/ANONYMOUS.

Notes

- Humanitarian source, interview with the author, Beirut, Lebanon, November 2017.

- “Statement by Ambassador Vassily A. Nebenzia, Permanent Representative of the Russian Federation to the United Nations, at the Security Council on the humanitarian situation in Syria,” Permanent Mission of the Russian Federation to the United Nations, November 29, 2017, http://russiaun.ru/en/news/gsyr2911.

- “Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator, Mark Lowcock: Statement to the Security Council on the humanitarian situation in Syria, 30 October 2017,” UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, Reliefweb, October 30, 2017, https://reliefweb.int/report/syrian-arab-republic/under-secretary-general-humanitarian-affairs-and-emergency-relief-73.

- Humanitarian source, interview with the author, Beirut, Lebanon, November 2017.

- Rick Gladstone, “U.N. Council, in Unanimous Vote, Backs Aid Delivery to Syrians in Rebel Areas,” New York Times, July 14, 2014, https://www.nytimes.com/2014/07/15/world/middleeast/un-security-council-authorizes-strengthened-syria-aid.html.

- “With Millions of Syrians in Need, Security Council Adopts Resolution 2165 (2014) Directing Relief Delivery through More Border Crossings, across Conflict Lines,” United Nations, July 14, 2014, https://www.un.org/press/en/2014/sc11473.doc.htm.

- The four named official crossings are Dara’a/al-Ramtha, with Jordan; Bab al-Hawa/Cilvegözü and Bab al-Salamah/Öncüpınar, with Turkey; and al-Ya’roubiyyeh/Rabi’ah, with Iraq. Other unofficial crossings that were already in use include, in addition to Fish Khabour, the Tal Shihab crossing with Jordan.

- “Implementation of Security Council resolutions 2139 (2014), 2165 (2014), 2191 (2014), 2258 (2015) and 2332 (2016) – Report of the Secretary-General (S/2017/982),” UN Security Council, Reliefweb, November 16, 2017, https://reliefweb.int/report/syrian-arab-republic/implementation-security-council-resolutions-2139-2014-2165-2014-2191-19

- “Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator, Mark Lowcock: Statement to the Security Council on the humanitarian situation in Syria, 29 November 2017,” UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, Reliefweb, November 29, 2017, https://reliefweb.int/report/syrian-arab-republic/under-secretary-general-humanitarian-affairs-and-emergency-relief-74.

- “Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator, Mark Lowcock: Statement to the Security Council on the humanitarian situation in Syria, 30 October 2017,” UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs.

- For one of the few instances where the issue has broken into the public discussion, see Somini Sengupta, “Russia Balks at Cross-Border Humanitarian Aid in Syria,” New York Times, December 6, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/06/world/middleeast/syria-russia-humanitarian-aid.html.

- Humanitarian source, interview with the author, Beirut, Lebanon, November 2017.

- Ibid.

- “Munzer: Al-Hukouma al-Souriyyah Mustamirrah fi Isal al-Musa’idat al-Insaniyyah Raghm Khurouqat al-Irhabiyyin fi Manatiq Takhfif al-Tawattur (Munzer: Syrian Government Continues to Deliver Humanitarian Assistance Despite Terrorists’ Breaches in De-escalation Zones),” SANA, November 29, 2017, https://www.sana.sy/?p=668443.

- Sam Heller, “Aleppo’s Bitter Lessons,” The Century Foundation, January 27, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/report/aleppos-bitter-lessons/.

- Aron Lund, “Russia has finished off the UN’s Syria chemical attack probe. What now?” IRIN News, November 20, 2017, https://www.irinnews.org/analysis/2017/11/20/russia-has-finished-un-s-syria-chemical-attack-probe-what-now.

- “Statement by Ambassador Vassily A. Nebenzia, Permanent Representative of the Russian Federation to the United Nations, at the Security Council on the humanitarian situation in Syria,” Permanent Mission of the Russian Federation to the United Nations.

- Humanitarian source, author’s interview, Beirut, Lebanon, November 2017.

- “Vladimir Putin visited Khmeimim Air Base in Syria,” President of Russia, December 11, 2017, http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/56351.

- Western diplomat, author’s interview, phone call, November 2017.

- Humanitarian, author’s interview, phone call, November 2017.

- Ibid.

- Humanitarian source, author’s interview, Beirut, Lebanon, November 2017.

- Ibid.

- Humanitarian, author’s interview, phone call, November 2017.

- Humanitarian source, author’s interview, Beirut, Lebanon, November 2017.

- Humanitarian, author’s interview, phone call, November 2017.

- Sam Heller, “Turkish Crackdown on Humanitarians Threatens Aid to Syrians,” The Century Foundation, May 3, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/report/turkish-crackdown-humanitarians-threatens-aid-syrians/.

- Aron Lund, “Opening Soon: The Story of a Syrian-Jordanian Border Crossing,” The Century Foundation, September 7, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/opening-soon-story-syrian-jordanian-border-crossing/.

- Provided to author by humanitarian source, November 2017.

- Humanitarian, author’s interview, phone call, November 2017.

- Humanitarian, author’s interview, Beirut, Lebanon, November 2017.

- Humanitarian, author’s interview, Beirut, Lebanon, November 2017.

- Humanitarian, author’s interview, phone call, November 2017.

- Humanitarian, author’s interview, Beirut, Lebanon, November 2017.

![On 13 November 2016, children lie or sit on the ground writing in notebooks at a make-shift school in rural Dar'a in the Syrian Arab Republic. Despite the ongoing violence across the country, children and dedicated teachers are doing all they can to keep their education going. Some 1.7 million children are currently (Nov 2016) out of school in the Syrian Arab Republic. Schools across the Syrian Arab Republic continue to be destroyed and damaged. This year (2016) 84 attacks on schools have resulted in the deaths of 69 children. UNICEF has provided 3.2 million children with learning materials, such as school bags, stationary and text books.

In November 2016, there is no safe place for children to learn or play in Syria. Underground facilities including basements and even caves, are used to shelter children from a war they grew up knowing nothing else. Displaced families from different areas in rural Damascus and Dar’a sought refuge in tents in rural Dar’a. The make-shift school receives up to 80 children on a daily basis. They are grouped according to age and knowledge in four groups, where each of the four former teachers, displaced themselves, teaches them reading and writing in both Arabic and English and the principals of mathematics. “There is not a single space or even an extra tent that we could’ve used as a learning space,” says [NAME CHANGED] Muhammad, a teacher in this school. “So we had to clean this fodder collection centre and turn it to a school where almost 80 children come on a daily basis to learn reading and writing, both in Arabic and English, and the principals of mathematics,” Muhammad continues. The children are divided into four groups based on their knowledge and age. Each group is taught by one of the four former teachers, two male and two female teachers. “Children have to share notebooks because we severely lack the necessary education supplies. They rotate on using the only six desks available.” [NAME CHANGED] Mona, a](https://production-tcf.imgix.net/app/uploads/2017/12/18173029/UN0415342-e1513632700225.jpg?auto=format%2Ccompress&q=80&fit=crop&w=1200&h=600)