In July, the nation witnessed political commentaries and tweets about saving the “Suburban Housewives of America,” but just who are these housewives? What voices speak for this group? What are their racial and economic backgrounds? As this national conversation pointed out, the answers to questions about who is included in this group—and importantly, who is kept out—are greatly determined by public policy.

While it is true that America’s suburbs are experiencing a racial and ethnic transformation, through which “suburban housewives” now comprise more working women of color, there is still a long way to go for these neighborhoods to be fully inclusive of low-wage Black and Latinx single mothers. As it turns out, America’s neighborhoods are still overwhelmingly racially segregated, with codified racist policies that confine Black, Latinx, and Indigenous people to under-resourced residential areas. Additionally and unsurprisingly, with local policies such as exclusionary zoning that racially and economically segregate our neighborhoods, the public schools that serve those neighborhoods are racially and economically segregated as well. In fact, America’s public schools are more segregated now than at any other time in the past half-century.

Parents of color, especially if they are low-wage workers, struggle daily with finding good schools for their children because it also requires navigating a housing system that was originally designed to keep them from living in affluent, predominantly White neighborhoods. How can these parents send their children to high-performing, well-resourced schools if they can’t find a place to live in the neighborhoods that these schools serve?

Parents of color, especially if they are low-wage workers, struggle daily with finding good schools for their children because it also requires navigating a housing system that was originally designed to keep them from living in affluent, predominantly white neighborhoods.

One successful solution to dismantling housing segregation is nonprofit housing mobility programs, such as the one offered in Fairfax County, Virginia, by Good Shepherd, the organization highlighted in this report. As part of a series of reports by The Century Foundation, my colleague, Richard Kahlenberg, and I interviewed residents of Good Shepherd to humanize the predominantly Black mothers who seek housing assistance. These mothers are often rendered invisible in current conversations of housing segregation. Centering these women also means centering the high-performing schools that these women could not access when they lived in their former neighborhoods.

This report highlights the captivating stories of two mothers who sought the best education for their children, against tremendous odds: Ms. Zulaika Hosten, a mother who endured domestic abuse and homelessness so that her eleven-year-old son, Robert, could be afforded a great education in Fairfax County Public Schools, and Ms. Charlotte Johnson,1 a mother of three who was formerly homeless, yet eventually was able to obtain affordable housing and to enroll her son in a high-performing school. The three takeaways from this report are: (1) for some mothers, particularly low-wage mothers of color, there are many obstacles in their way, particularly the lack of affordable housing in residential areas that are served by good schools; (2) in some counties, such as Fairfax, there are affordable housing and inclusionary zoning policies that help low-wage families, such as those led by Ms. Hosten and Ms. Johnson, access good school systems; and (3) for low-wage mothers, there are exceptional nonprofit programs, such as Good Shepherd, that can help them navigate the tricky landscape in order to obtain affordable housing in residential areas served by good schools.

The report first will explore the journeys of Ms. Hosten and Ms. Johnson, and then will provide background on affordable housing and education in Fairfax County Public Schools, as well as key insights from the interviews that reinforce why housing policy is school policy.

Ms. Zulaika Hosten’s Story

On February 5, 2020, researchers at The Century Foundation interviewed Ms. Zulaika Hosten on her housing and school experiences. Ms. Hosten is a thirty-year-old African-American woman and single mother, originally from Brooklyn, New York. She is a full time medical assistant and nursing student. Ms. Hosten lived in New York until her son, Robert, was five years old. Robert spent his early years at a lower-performing school in Washington Heights, Manhattan, where Ms. Hosten was dissatisfied with the school quality—prompting her move to Fairfax County, Virginia, where she herself had been educated. At the school in Washington Heights, only 34 percent of students met state standards on the state English test and 40 percent met the state standards for math.2 The school in Washington Heights was also racially and economically segregated: 80 percent of students were Hispanic or Latinx, 14 percent were Black, 4 percent were White, and 1 percent were Asian,3 and 93 percent of students were from low-income families.4 Ms. Hosten emphasized that, “I knew that if I took him [Robert] to a suburban area that he would have a better education.”5

Ms. Hosten was confident in this statement based on her personal experience of attending a few years at an elementary school in Fairfax County. Her mother sent her to Manassas, Virginia to live with her grandmother just so she could attend Fairfax County Public Schools, well known as a high-performing district. Ms. Hosten noticed the stark differences in school quality in Fairfax County compared to the school in New York City. For example, in Fairfax County, the student–teacher ratios are lower, and in Ms. Hosten’s words, “the curriculum is more in-depth.”6

Ms. Charlotte Johnson’s Story

The Century Foundation also interviewed Ms. Charlotte Johnson about her housing and school experiences. Ms. Johnson is an African-American single mother originally from Richmond, Virginia. She is a registered nurse who cares for people in their homes and in the hospital. She is currently studying to become a licensed practical nurse (LPN). She is the mother of three sons, and while she was living in Prince William County, she was able to enroll her youngest son, Justin, in Hylton High School. Ms. Johnson now lives in more stable and suitable housing in Fairfax County, thanks to the Good Shepherd program, but she chose to keep Gregory enrolled at Hylton High School, rather than transfer him to another school for his final year.7 Hylton High School was almost an hour away from Ms. Johnson’s’s home in Fairfax County by car, but she continued to make the trip because she truly appreciated what was on the other end: a great high school in the Prince William County Public School system. (Were she able to move to Fairfax County earlier, she may have felt more comfortable having Gregory transfer to a school there.)

The Century Foundation chose to interview Ms. Johnson based on her unique experience of making it off of the waiting list to receive affordable housing. Ms. Johnson has a success story, but unfortunately, as my colleague highlighted in a report on the experience of Ms. Williams, hundreds and thousands of low-wage mothers are not fortunate enough to have this success story, and do not make it off the waiting list, leaving them confined to segregated neighborhoods and unsatisfactory schools.

Academic and Demographic Background on Prince William County Public Schools

Ms. Johnson was initially drawn to Prince William County for the excellence of its schools. Prince William County Schools comprise the second-largest school system in Virginia, and the thirty-fifth largest in the United States.8 The school system has over 90,000 students and is fairly diverse. Approximately 36 percent of students are Hispanic, 20 percent are Black, 30 percent are White, 9 percent are Asian, and 6 percent are multiracial. Additionally, approximately 26 percent of students are English language learners.9

At Hylton, the school in Prince William County that Ms. Johnson’s son Justin attended, 88 percent of students are proficient in reading, 82 percent in Algebra I, and 97 percent in geography. The school is racially and economically diverse as well: 38 percent of students are Hispanic, 27 percent are Black, 19 percent are White, 8 percent are Asian, 7 percent are biracial, and 43 percent of students come from low-income families.10

Compared to Richmond City Public Schools, where Ms. Johnson previously resided, school quality in Prince William County typically prevails. Richmond Public Schools have a graduation rate of 75 percent,11 while Prince William County touts a graduation rate of 92 percent.12 In contrast to the diversity in Prince William County, Richmond City Public Schools are predominantly segregated, with 75 percent of students being African-American, 9 percent White, and 1 percent Asian. As of 2015, 75 percent of students were eligible for free and reduced price lunch.13 The school rating website Niche gave Richmond City Public Schools a D+ as overall grade,14 compared to Prince William County Schools, which received a B+.15

Academic and Demographic Background on Fairfax County Public Schools

It is not hard to understand why both Ms. Hosten and Ms. Johnson were drawn to Fairfax County (even though Ms. Johnson eventually chose not to have her son transfer to a Fairfax County school). The Fairfax County Public School system, where Ms. Hosten’s son attends school, has 188,000 students, placing it as the tenth-largest school system in the nation, and the largest in Virginia.16 Schools in Fairfax County are generally known to be high performing: approximately 92 percent of students graduate on time, and more than 92 percent plan to pursue an education after high school. This is higher than the national graduation rate for high school students (85 percent).17 Fairfax County high schools are recognized as being the most challenging in the United States, with the graduating class of 2019 including 254 National Merit Scholarship semifinalists.18 Additionally, Fairfax County is on track to provide laptops to all students in the third grade and above by 2023. All high school students received a laptop in the 2019–20 school year. The stated rationale behind providing students with a laptop is to foster critical thinking skills, communication, and collaboration among students.19

Fairfax County high schools are recognized as being the most challenging in the United States, with the graduating class of 2019 including 254 National Merit Scholarship semifinalists.

Fairfax County Public Schools are fairly diverse. Families in Fairfax County are generally middle class to upper-middle class, and well-educated. The county’s median household income of $103,010 is one of the highest in the nation, and is higher than the state’s median of $60,674 and approximately double the national median of $50,046.20 Among students enrolled, 28 percent are eligible for free and reduced price lunch,21 approximately 39 percent are White, 26 percent are Hispanic, 20 percent are Asian, 10 percent are Black, 5.5 percent are Multiracial, and less than 1 percent of students are American Indian or Native Hawaiian.22

Fairfax County is a highly appealing area for families seeking a high-performing and reputable school district. Fortunately, Fairfax County has generally been on the right side of history in providing affordable housing, so many families who may not be as affluent may access their schools.

A Brief History of Affordable Housing in Fairfax County

Fairfax County was progressive in passing the nation’s first inclusionary zoning ordinance in 1971. The original ordinance in Fairfax County had a mandatory requirement that, in multifamily zones, 15 percent of all units in multifamily projects with more than fifty units be set aside to households earning between 60 percent and 80 percent of the area median income (AMI) in the Washington, D.C. metropolitan area. However, the Virginia Supreme Court overturned this ordinance in 1973, on the basis that the county did not provide just compensation for the production of affordable housing.23 Additionally, Virginia is a “Dillon Rule”24 state, meaning that local government authority applies only to the rights explicitly given to it by the state legislature and state constitution. Fairfax County needed state legislative permission to adopt the original ordinance, and it had not obtained approval.25 Through advocacy and lobbying efforts from a Fairfax-based coalition called Affordable Housing Opportunity Means Everyone (AHOME), Virginia eventually passed an amendment that permits local jurisdictions to pass inclusionary zoning ordinances in 1989.26

The ordinance currently in effect was approved in 1990, when the County Board of Supervisors established the Affordable Dwelling Unit program. The Affordable Dwelling Unit program provides affordable housing options for low- and moderate-income households across Fairfax County. In Fairfax County, the program is managed by The Fairfax County Redevelopment and Housing Authority (FCRHA), with requirements of both for-sale and rental properties to set aside a share of units for households earning between 50 percent and 70 percent of the Washington, D.C. metropolitan AMI. This particular ordinance does not include housing development in five areas of the county: the town of Clifton, the city of Falls Church, the city of Fairfax, the town of Herdon, and Vienna. The local municipal governments in this area have the authority to make zoning decisions.27 In return for providing these affordable units, the developer receives a “density bonus,” is given in return,28 which may include expedited approvals or increased density allowances.29 The U.S. Housing and Urban Development has observed that inclusionary zoning has emerged as a proven strategy to address the lack of affordable housing with the potential for creating socially and economically diverse communities.30

Barriers to Affordable Housing That Remain in Fairfax County

Despite Fairfax County’s progressive history, efforts to promote affordable housing are not always embraced by its residents, and there is still much work to be done.31 For example, while neighboring (and slightly smaller) Montgomery County produces a range of 77 to more than 1,200 affordable housing units annually, Fairfax County only manages to produce a range of 18 to 375 units per year. The difference in ranges reflects the opportunities that each county has for housing production due to zoning.32

Despite Fairfax County’s progressive history, efforts to promote affordable housing are not always embraced by its residents, and there is still much work to be done.

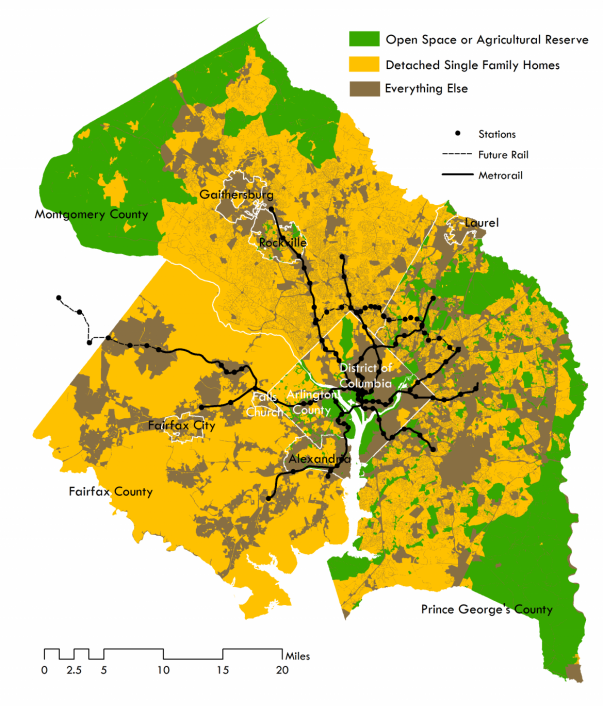

Fairfax County has a significantly higher percentage of residential areas zoned for single families. While single-family zoning is often touted as “protecting the character” of neighborhoods from denser development, it has recently—and deservedly—come under fire33 because it not only works against housing affordability, but also promotes racist and socioeconomic housing discrimination as well as accelerates climate change. Racist stereotypes often employed in arguments in support of single-family zoning that low-income African-American, White, and Latinx families will move into these areas, drive home values down, and bring criminality. As of 2018, 77 percent of housing lots in Fairfax County were zoned for single-family, detached houses, the highest for any jurisdiction in the Washington Metropolitan Area.34 Fairfax City comes second in the region, with 54 percent zoned as single family, and Montgomery County third, with 48 percent of homes zoned as single family.35

Map 1. Residential Zoning in the Washington, D.C. Region

Impacts of Affordable Housing on Residents in Fairfax County

Racially, ethnically, and economically diverse households have benefited from the inclusionary zoning ordinance in Fairfax County. Between 1993 and 2000, 41 percent of Fairfax’s inclusionary housing participants were Asian, 26 percent were White, 23 percent were Black, and 9 percent were Latinx.36 The average income of families that purchased a home was $34,742. Single-parent households accounted for almost 25 percent of purchasers, while 15 percent of purchasers had previously lived in public housing or were recipients of a Section 8 housing voucher. Studies on Fairfax’s inclusionary zoning ordinance have found that it has promoted racial and economic integration throughout the county.37

Fairfax was seeking to more than double the funding for its affordable housing loan program, with the new budget proposing more than $45.7 million for affordable38 development.39 If the proposed increase to the loan program was approved, Fairfax would have offered more funding to affordable housing developers annually than any other county in Northern Virginia.40 Unfortunately, due to competing priorities amid the COVID-19 pandemic, the $23 million that was earmarked for creating and retaining affordable housing in Fairfax County was cut from the budget.

Impact of Good Shepherd Housing

Housed in Alexandria, Virginia, Good Shepherd Housing is a nonprofit that has served the housing needs of Northern Virginia families and individuals for more than forty years.41 Their mission is “to reduce homelessness, increase community support, and promote self-sufficiency.”42 Of the households Good Shepherd helps, 83 percent are families with children, and they provide stable housing among other services for more than 1,000 working-class families annually. 43

Residents seeking housing through Good Shepherd can apply online to be accepted, and the program also receives referrals from housing shelters that assist survivors of domestic abuse, and New Hope Housing Inc., a nonprofit that assists homeless individuals. Through Good Shepherd, residents can access affordable housing, paying a subsidized version of market-pay rent. People typically apply to Good Shepherd when they cannot afford market rate rent.44 Good Shepherd’s residents must meet income requirements, and only 30 percent of the residents’ income should go toward rent. Currently, subsidized rent for a one-bedroom apartment is $1,000, a two-bedroom is $1,200, and a three bedroom is $1,300.45

Ms. Hosten and Ms. Johnson are both recipients of affordable housing through Good Shepherd and now live in Fairfax County. Ms. Hosten learned about Good Shepherd when living in transitional housing. At first, she was living in Bethany House, a shelter for victims of domestic violence, and they referred her to Christian Relief Services. Christian Relief Services helps residents become self-sufficient throughout a two-year period. At the end of the two-year period in February 2019, Ms. Hosten did some independent research and found out about Good Shepherd. She describes Good Shepherd and their staff as “angels and saving grace.” Fair housing nonprofits such as Good Shepherd have helped mothers like Ms. Hosten have housing stability and, consequently, access to high-performing schools.

The moving-in process for Ms. Hosten was challenging, but she is thankful to have had Ms. Aleisha Wilhite and Ms. Pamela Pinneros as her advocates and for being very responsive to her needs. For example, when Ms. Hosten first moved into her unit, the door appeared to have been kicked in, and as a domestic abuse survivor, Ms. Hosten emphasized that “I felt uncomfortable and sent pictures to Ms. Pinneros to prove why this was an issue for me and my son.” Thankfully, she received a new door, and Ms. Hosten underscores the importance of advocating for herself. Ms. Hosten emphasized that “everyone should be afforded the same opportunity, and to not be grateful for a housing service just because we are poor.” Similarly, Ms. Hosten describes Ms. Wilhite as an advocate, and Ms. Pinneros was “instrumental in getting the door secured.” Ms. Hosten comments that her involvement with Good Shepherd has been “a great experience. I am 100 percent happy and very satisfied.” Staffers at Good Shepherd were instrumental in the positive moving experience for Ms. Hosten.46

Ms. Hosten emphasized that “everyone should be afforded the same opportunity, and to not be grateful for a housing service just because we are poor.”

Similarly, Ms. Johnson had a positive experience with Good Shepherd Housing.47 Prior to Good Shepherd, Ms. Johnson was homeless. She searched for housing assistance programs through dialing 611 and 222 , which in Virginia are numbers for public information. She eventually learned about the Good Shepherd program, filled out the application, and was put on the waiting list. Ms. Johnson was persistent and it paid off. She called and sent emails every week, and was finally accepted in Good Shepherd.48 Ms. Johnson is a recipient of a federal Project-Based Voucher, which is based on income.49 Fairfax County also assists with paying for a portion of her rent, and Aleisha Wilhite commented that “the good thing about [Project-Based Voucher], is when you report a loss of income, Fairfax County pays for it during times such as COVID-19.”50 There also was a time when Ms. Johnson needed financial assistance to pay for summer school for her son, and Good Shepherd helped her.51

The Intersections of Housing and Education

For Ms. Hosten, Good Shepherd provided her with much more than a roof over her head—they broadened life’s opportunities for her son, Robert. For her, her son having access to Fairfax County Public Schools was a dream come true. At Franconia Elementary School, Ms. Hosten noticed the genuine investment the school made in its students, from the school’s principal to the guidance counselor, and she returned that same parental investment. The guidance counselor, for example, called Ms. Hosten provided progress reports on Robert’s performance in math at school, and arranged for Robert to receive extra tutorial service outside of the school.52

Franconia Elementary is high performing, with 83 percent of students proficient in math, and 85 percent of students proficient in reading. The school is also racially and socioeconomically diverse, with White students making up 38 percent of the enrollment, followed by Hispanic students at 22 percent, Black at 17 percent, Asian at 15 percent, multiracial at 7 percent, and with 16 percent of students eligible for free lunch.53 Ms. Hosten underscored that her son attended a racially segregated school when they lived in New York, and she compared the infrastructure of that school to “being in prison because there were bars on the windows.”54

When asked about the school’s funding, Ms. Hosten commented that “to say they have money would be an understatement.” For Ms. Hosten, Fairfax County is an exemplar in enriching the lives of students through after-school, summer, and STEM programs. She wished these forms of enrichment had been offered where she and her son lived previously.

For Ms. Johnson, when asked about Hylton High School, she commented that Hylton High School is “very diverse, has great access to resources, and the parents are involved.” Ms. Johnson has an uplifting story of being one of the fortunate people who made it off of the waiting list and into suitable housing, and is very happy with the quality of schools.

Looking Forward

The stories of Ms. Hosten and Ms. Johnson are compelling, and are just two of the countless experiences of single mothers wanting the best education for their children. Too often, single mothers—particularly those who are Black and brown—are marginalized in society and assumed not to care about their child’s education. This is a part of a series to disrupt this narrative, and to place names to housing assistance programs that have directly benefited people.

Excitedly, the nation recently experienced a historic moment: the selection of the first Black and South Asian-American woman as a vice presidential nominee—Senator Kamala Harris. In the wake of the murder of Mr. George Floyd, the global protests for racial justice, and the selection of Senator Harris, the world has seen that the voices, brilliance, and experiences of Black women matter. Storytelling is just the beginning. To ensure more Black mothers like Ms. Hosten and Ms. Johnson have opportunities, dismantling single-family zoning policies must occur, along with blatant efforts to dismantle racism.

The education team at The Century Foundation graciously thanks Ms. Hosten and Ms. Johnson for speaking candidly when sharing their stories, as well as Ms. Aleisha Wilhite and Ms. Pamela Pinneros of Good Shepherd Housing. Their resilience is uncompromised, and shows that educators, advocates, and policymakers have much work to accomplish. The journey continues, and in the spirit of the late Congressman John Lewis, good trouble must be stirred until racial justice is obtained for all of humanity.

Notes

- This name is an alias to protect the privacy of the interviewee.

- “P.S. 028 Wright Brothers,” 2018–19 school year, New York Department of Education, https://tools.nycenet.edu/snapshot/2019/06M028/EMS/#INFO.

- Ibid.

- “PS 28 Wright Brothers,” Great Schools, https://www.greatschools.org/new-york/new-york/2112-Ps-28-Wright-Brothers/.

- Zulaika Hosten, telephone conversation with author, February 5, 2020.

- Ibid.

- Aleisha Wilhite, telephone conversation with author, April 20, 2020.

- “About Us,” Prince William County Public Schools, https://www.pwcs.edu/cms/One.aspx?portalId=340225&pageId=769123.

- Ibid.

- “C.D. Hylton High School,” Great Schools, https://www.greatschools.org/virginia/dale-city/1341-C.D.-Hylton-High-School/.

- “RPS Confronts Failing Graduation Rates Head-on,” Richmond Public Schools, https://www.rvaschools.net/site/default.aspx?PageType=3&DomainID=4&ModuleInstanceID=71&ViewID=6446EE88-D30C-497E-9316-3F8874B3E108&RenderLoc=0&FlexDataID=25176&PageID=1.

- “On-time Graduation Rate Surpasses State Average,” Prince William County Public Schools, http://www.pwcs.edu/news/2019-20_news/on-time_graduation_rate_surpasses_state_average.

- “A Publication of Richmond Public Schools,” Richmond Public Schools, http://web.richmond.k12.va.us/Portals/0/assets/HR/pdfs/CGCS21%20Recommendations/Appendix%20C%20-%20MARCH15HRBROCHURE_B.pdf.

- “Richmond City Public Schools,” Niche, https://www.niche.com/k12/d/richmond-city-public-schools-va/.

- “Prince William County Public Schools,” Niche, https://www.niche.com/k12/d/prince-william-county-public-schools-va/.

- “About Us,” Fairfax County Public Schools, https://www.fcps.edu/about-fcps.

- “Public High School Graduation Rates,” National Center for Education Statistics, May 2019, https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_coi.asp.

- “About Us,” Fairfax County Public Schools, https://www.fcps.edu/about-fcps.

- Debbie Truong, “Logging on to learn: All Fairfax County high schools students getting laptops,” Washington Post, August 11, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/education/logging-on-to-learn-all-fairfax-county-high-school-students-getting-laptops/2019/08/11/7fb69136-b953-11e9-a091-6a96e67d9cce_story.html.

- U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, “Expanding Housing Opportunities Through Inclusionary Zoning: Lessons From Two Counties,” December 2012, https://www.huduser.gov/portal/publications/HUD-496_new.pdf.

- Heather Long, “Hidden crisis: D.C.-area students owe nearly half a million in K-12 school lunch debt,” Washington Post, December 28, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2018/12/28/hidden-crisis-dc-area-students-owe-nearly-half-million-k-school-lunch-debt/?arc404=true.

- “About Us,” Fairfax County Public Schools, https://www.fcps.edu/about-fcps.

- “Expanding Housing Opportunities Through Inclusionary Zoning: Lessons From Two Counties,” U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, December 2012, https://www.huduser.gov/portal/publications/HUD-496_new.pdf.

- “Expanding Housing Opportunities Through Inclusionary Zoning: Lessons From Two Counties,” U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, December 2012, https://www.huduser.gov/portal/publications/HUD-496_new.pdf.

- “Expanding Housing Opportunities Through Inclusionary Zoning: Lessons From Two Counties,” U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, December 2012, https://www.huduser.gov/portal/publications/HUD-496_new.pdf.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- “Inclusionary Zoning: An Important Avenue to More Affordable Housing,” Virginia Poverty Law Center, January 30, 2018, https://vplc.org/inclusionary-zoning-an-important-avenue-to-more-affordable-housing/.

- “Expanding Housing Opportunities Through Inclusionary Zoning: Lessons From Two Counties,” U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, December 2012, https://www.huduser.gov/portal/publications/HUD-496_new.pdf.

- “Expanding Housing Opportunities Through Inclusionary Zoning: Lessons From Two Counties,” U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, December 2012, https://www.huduser.gov/portal/publications/HUD-496_new.pdf.

- Ibid.

- Kimberly Quick and Richard D. Kahlenberg, “Attacking the Black–White Opportunity Gap That Comes from Residential Segregation,” The Century Foundation, June 25, 2019, https://tcf.org/content/report/attacking-black-white-opportunity-gap-comes-residential-segregation/.

- Tracey Hadden Loh, “Where the Washington region is zoned for single-family homes: an update,” Greater Greater Washington, December 18, 2018, https://ggwash.org/view/70232/washington-region-single-family-zoning-an-update.

- Ibid.

- “Expanding Affordable Housing Through Inclusionary Zoning: Lessons from the Washington Metropolitan Area,” Brookings Institution Center on Urban and Metropolitan Policy, October 2001, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/inclusionary.pdf.

- Ibid.

- Antonio Olivo, “Fairfax County moves toward more austere budget amid coronavirus crisis,” Washington Post, May 5, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/virginia-politics/fairfax-county-moves-toward-more-austere-budget-amid-coronavirus-crisis/2020/05/05/b434dea6-8f0c-11ea-9e23-6914ee410a5f_story.html.

- Alex Koma, Fairfax County could soon massively ramp up its affordable housing spending,” Washington Business Journal, https://www.bizjournals.com/washington/news/2020/02/26/fairfax-county-could-soon-massively-ramp-up-its.html

- Ibid

- “About GSH,” Good Shepherd Housing, https://goodhousing.org/about-good-shepherd-housing/

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Aleisha Wilhite, telephone conversation with author, April 20, 2020.

- Aleisha Wilhite, telephone conversation with author, April 20, 2020.

- Zulaika Hosten, telephone conversation with author, February 5, 2020.

- Aleisha Wilhite, telephone conversation with author, April 20, 2020.

- Ms. Johnson, telephone conversation with author, April 8, 2020.

- Aleisha Wilhite, telephone conversation with author, April 20, 2020.

- Aleisha Wilhite, telephone conversation with author, April 20, 2020.

- Aleisha Wilhite, telephone conversation with author, April 20, 2020.

- Zulaika Hosten, telephone conversation with author, February 5, 2020.

- “Franconia Elementary School,” Public School Review, https://www.publicschoolreview.com/franconia-elementary-school-profile/22310.

- Zulaika Hosten, telephone conversation with author, February 5, 2020.