The United States has substantially scaled back its ambitions in Syria. Earlier this year, America cancelled its covert support for rebels fighting the regime of Bashar al-Assad.1 Washington is now only vaguely committed to a United Nations-sponsored process to resolve the conflict.

U.S. policy in Syria can now mostly be reduced to two lines of effort: the coalition military campaign against the self-proclaimed Islamic State, and, over the past several months, a diplomatic push for a “de-escalation” agreement covering Syria’s southwestern corner. The former effort is going swimmingly—the Islamic State’s de facto Syrian capital of Raqqa has fallen. The U.S.-led coalition has killed jihadists in the multiple, multiple thousands.

But the de-escalation agreement—one of America’s last good projects in Syria—is quietly endangered.

The southern de-escalation is one U.S. effort in Syria that has so far taken root and bloomed, even as the rest of the country’s war has been, for Washington, a policy desert. The local and geopolitical factors governing Syria’s southwest have permitted a ceasefire that has saved lives and, with work and luck, could become something more. But all that could collapse if, as scheduled, America’s covert support for southern rebels halts abruptly in December, and if Washington and its allies don’t start laying the groundwork for a political resolution in the south.

The de-escalation, a sort of more involved ceasefire, is the product of months of trilateral talks among the United States, Russia, and Jordan in Jordan’s capital Amman. The agreement has been embraced by the U.S. government at the highest level. After the Hamburg G20 summit in July, President Trump himself held it up as an example of successful U.S.-Russian cooperation.

But based on interviews in Amman with officials, rebels, humanitarians, journalists, and others, the agreement may be somewhat less than meets the eye—a set of tactical steps that don’t obviously translate into a way forward politically for Syria’s south. And the de-escalation also faces a more urgent threat, as the separate U.S. government decision to halt the covert provision of arms and salaries to southern rebels threatens to throw the south into chaos, de-escalation deal or no. Salaries for anti-Assad rebels stop in December; unless someone finds a new way to pay them, thousands of armed men are suddenly going to be in need of money and out of anyone’s effective control.

The mood in Amman is uneasy, clouded by uncertainty over U.S. intentions and commitment—even to a corner of Syria in which America has made a demonstrable investment and where it has a clear strategic interest. The southern de-escalation agreement has so far been a rare policy success for Washington in Syria. But without new action, U.S. diplomatic efforts may have been for nothing.

The Southern De-Escalation

U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson announced the “de-escalation” agreement covering Syria’s southwest on July 7.2 The deal was unveiled in the wake of Trump and Putin’s meeting at the G20 summit the same day, and followed months of discussions between U.S. and Russian officials.3 “We negotiated a ceasefire in parts of Syria which will save lives,” Trump tweeted several days later. “Now it is time to move forward in working constructively with Russia!”4

…We negotiated a ceasefire in parts of Syria which will save lives. Now it is time to move forward in working constructively with Russia!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) July 9, 2017

The agreement was part of a broader reorientation of U.S. policy in Syria towards the reduction or “de-escalation” of violence—unilaterally, if necessary—in Syria’s central civil war between the Assad regime and the mixed revolutionary-jihadist opposition). The shift is meant both to reduce civilian suffering and to provide a space for political progress towards ending the war—but also, at a minimum, to stop fueling the war towards no obvious end.

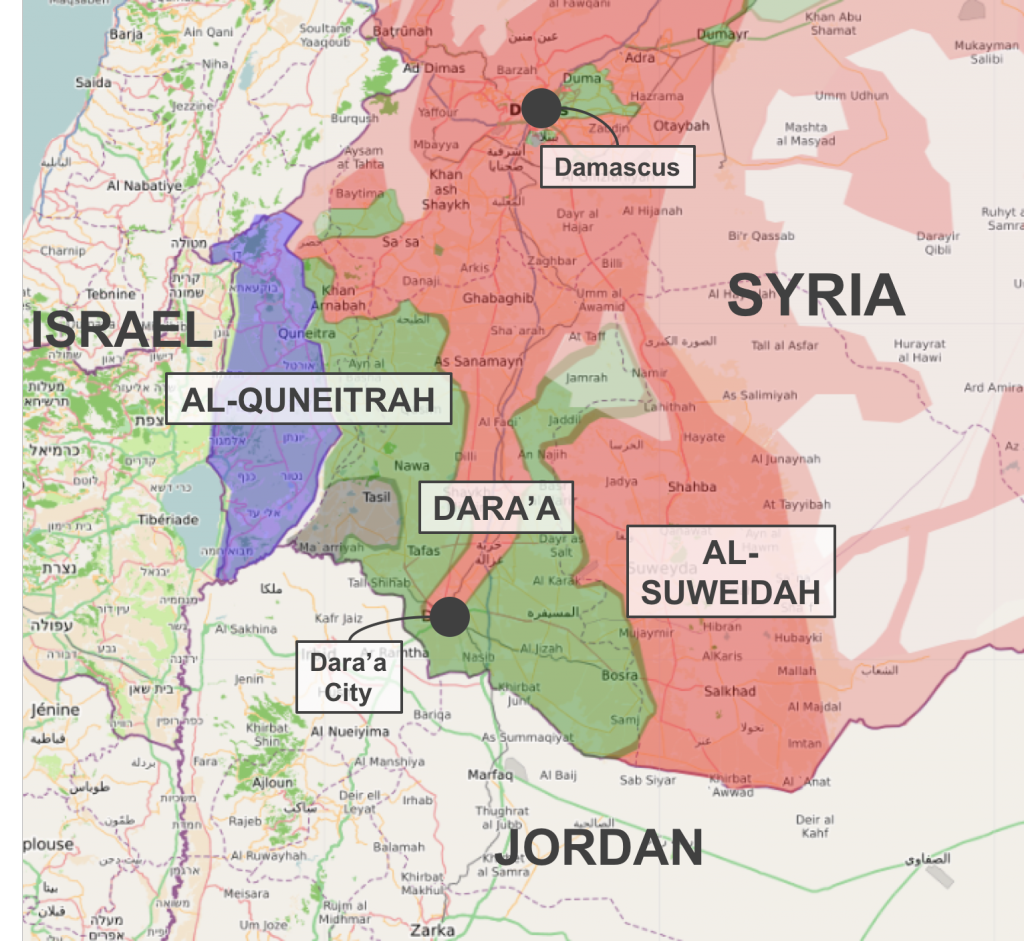

U.S. diplomats had previously tried and failed to secure nationwide ceasefires in Syria, but this time, they focused narrowly on the southwestern provinces of Dara’a and al-Quneitra, which seemed uniquely auspicious. The United States and Jordan could exercise more effective control over rebels in the south—as opposed to Syria’s more unruly, Islamist- and jihadist-dominated north—and the south had been kept relatively quiet since 2015. The United States has an especially compelling interest in the south, whose security and stability is of vital importance for neighboring countries and U.S. allies Israel and Jordan. Both countries also have positive relationships with Russia, making their national security a matter of shared great-power interest, and both have been keen to find a way to keep the Assad regime’s Iranian-backed militia allies away from their borders.

The July 7 de-escalation agreement was not born fully formed, and since July, talks between the deal’s sponsors have continued in Amman. At the time of the July announcement, they had settled on a ceasefire along an agreed-upon line of contact. That ceasefire went into effect on July 9 and has mostly held until now.

“What we don’t want to do is create the sense that this ceasefire is it and we’re done and now we move on to some other parts of Syria,” a senior State Department official said at the time, briefing the press on background. “It is this ceasefire that sets in place the basis for ongoing discussions about how that is solidified and made durable in southwest Syria.”5

The course of the negotiations and the exact terms of the de-escalation agreement are extremely closely held. I’ve learned, however, that the agreement has now been fleshed out from the initial ceasefire and halt to aerial bombing to include a more defined map—complete with zones behind the primary line of contact meant to be free of “non-Syrian” forces, in this case Iranian-backed militias—as well as the establishment of a joint ceasefire monitoring cell in Amman. According to a diplomatic source familiar with the negotiations, though, the agreement has yet to be formalized in an official memorandum and could still evolve.6

Now talks have leapfrogged to reopening the Nasib border crossing that connects Dara’a province with Jordan.7 The opening of the crossing would allow for the resumption of commercial shipping between Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, and the Gulf beyond and help rejuvenate Jordan’s ailing economy. But talks have made little apparent headway, as they’ve gotten hung up on practical questions of how to share administration of the crossing and on unpalatable symbolic concessions—what flags to fly overhead, and how the reopening of the crossing for use by Damascus can be anything other than a blow to the morale and legitimacy of local rebels.8

The reopening of a border crossing is not an actual political vision for Syria’s rebel-held southwest, or for how it will relate to a central Syrian state controlled by the Assad regime.

But the reopening of a border crossing is not an actual political vision for Syria’s rebel-held southwest, or for how it will relate to a central Syrian state controlled by the Assad regime. The de-escalation agreement does not entail a political roadmap for the south, beyond a vague commitment to a negotiated political solution to the war—something that is, fairly evidently, not forthcoming.9

“The premise of the negotiations about the de-escalation area has not been to negotiate a political arrangement between these two parts [i.e., the opposition-held south and Damascus],” said a Western diplomat who agreed to speak on condition of anonymity. “The premise of de-escalation has been getting calm on an enduring basis.”10

But what comes next? That the negotiations have progressed this far, and through thorny issues including the extent of Iranian-backed militia presence, is an accomplishment. And the ceasefire has resulted in a tangible, life-saving reduction in violence,11 although some violations have persisted—the regime has continued to push on the rural town Beit Jinn, west of Damascus12, for example, which is technically covered by the de-escalation.

But suppose the Nasib issue can be resolved and the ceasefire made perfect—what then? No one I spoke to in Amman seemed to know, and it made them nervous.

And in the meantime, there are more immediate threats to the de-escalation—or really, one big threat.

December Looms

The December cutoff for U.S. support seemed to be basically common knowledge among contacts in Amman, including officials, rebels, and even people involved in civilian humanitarian and stabilization assistance. December had big, still-unknown implications for all of them.

Most of southern Syria’s rebels have been coordinated and supplied with arms and ammunition, salaries, and logistical support through a joint intelligence cell in Jordan called the Military Operations Command (MOC). The MOC has included—in roughly descending order of relevance—the United States, Jordan, the United Kingdom, the United Arab Emirates, and Saudi Arabia, as well as several other allied states in an observer capacity. Rebel factions linked to the MOC have collectively been branded the “Southern Front.”

When the end of the CIA program was first announced in July, I was told that the program would continue in southern Syria in some modified form.13 That proved to be incorrect. Others in Amman told me they had also expected some carveout for the south, if only to buttress the de-escalation. Also incorrect. Pending some change in course, covert U.S. support in the south comes to a hard stop in December.

At least some other countries in the MOC are expected to follow the U.S. lead and pull their support, unwilling to go on without America’s political cover, although the final count of who is in and who is out remains unclear. Jordan itself has traditionally played a supervisory and coordinating role, and it is seen as incapable of providing extensive material support.

The Southern Front was formed in February 2014 from roughly fifty local factions, but it was always more of a brand than one coherent entity. With few imminent external threats from either the regime or—as in Syria’s rebel north—a single predatory jihadist faction, the Southern Front’s factions joined up in ad hoc operations rooms for specific battles, but didn’t need to consolidate or establish a unitary command. Even when factions ostensibly merged, the MOC’s support to the individual commanders of those pre-merger factions continued unchanged. “There were never any real mergers in the Southern Front. They were basically alliances, or mergers that were imaginary, on paper,” said Ghazi Abbas, external representative for al-Quneitra faction the Furqan Brigades.

“The Southern Front is divided into cantons that answer to international parties,” Abbas told me. “The media says the Southern Front is the most organized. But in reality, it’s broken up, fragmented, and stripped of decision-making power.”14

“[The MOC’s members] support factions individually,” said Ibrahim al-Jebawi, founder and head of the Syrian Media Organization, a revolutionary media outlet linked with the Southern Front’s rebels. “They never tried to bring these factions together under one banner. And even if they brought them together under the so-called ‘Southern Front,’ every faction kept its emir, its commander, through whom support would be provided.”15

Still, even a relatively headless Southern Front has been a military force to be reckoned with—particularly on the defensive—and one the regime and its allies could not just run over. Dara’a’s provincial capital witnessed fierce fighting early this year as rebels attacked, they said, to pre-empt a regime offensive towards Nasib.16 After months of clashes, the battle ended in a rough stalemate.

Southern rebels’ military strength is part of the calculus of the south’s de-escalation. The withdrawal of U.S. and allied support threatens to change that math, sabotaging America’s own expressed intentions.

A halt to supplies of arms and ammunition seems to be less of a concern than the halt to fighters’ MOC-paid salaries. In Amman, I heard estimates of Southern Front’s manpower ranging from 10,000 to 37,000—whatever the real number, after December those fighters will need money to support themselves and their families.

“There are tens of thousands of fighters and families who are going to need gainful employment,” a Western diplomat told me. “The task is ensuring people have livelihoods—their ability to feed and clothe their families. That needs to be addressed.”17

Criminality, drug trafficking, and rebels’ mini-warlordism are already major sources of insecurity in the opposition-held south.18 The south’s supreme Dar al-Adl court has only limited writ, frustrated by uncooperative rebel factions or powerful local clans that protect their own. And rebels have so far proved incapable of effective security coordination, even to frustrate a wave of unclaimed IED assassinations of rebels, activists, and civil-society figures.19 “The Free Syrian Army isn’t capable of controlling things, because it’s itself the cause of this chaos,” said Ali al-Maf’alani, external representative for the south’s Free Lawyers’ Syndicate.20

Whatever problems the south now faces in terms of a breakdown of law and order, they seem likely to explode if the salaries are abruptly cut off and thousands of armed rebels suddenly need to do their own fund-raising.

But whatever problems the south now faces in terms of a breakdown of law and order, they seem likely to explode if the salaries are abruptly cut off and thousands of armed rebels suddenly need to do their own fund-raising. That’s in addition to myriad other concerns—rebels smuggling arms or drugs (or people) across the Jordanian border, selling their arms on to local jihadists or the Assad regime, or just defecting to one or the other outright. Jihadists are a more geographically and numerically limited force in southern Syria than in the north, but they are poised to capitalize on the disintegration of the Southern Front.21

The de-escalation agreement depends on the continued coherence and compliance of southern rebels. Exhausted rebels and their civilian constituencies have their own motivations to stick with the ceasefire, but the sudden halt in support and, with it, much of rebel backers’ leverage over local rebels will push the south in unpredictable, dangerous directions.

Someone needs to step in and pay these salaries—if not the United States, then another interested ally. The salaries can be relabeled or masked as something else, if necessary. Rebels can be called border guards, or a counter-jihadist force. The important thing is that if the money just stops in December, the south is set to go haywire.

No Certain Future

If the de-escalation survives December, the agreement’s political endpoint is still a mystery. Realistically, this is not something that can be put off until an imaginary national political settlement.

No party involved in the south, local or international, is interested in Syria’s partition or in the secession of southern Syria. But if Syria is to remain intact, then how the rebel south rejoins a Syrian whole matters. The south’s reintegration in the central Syrian state can play out in different ways—it can be orderly and negotiated, or it can be chaotic and bloody, with serious ramifications both for the area’s people and for their state backers.

Those backers, to date, have not set up the south to successfully negotiate with Damascus. Deliberately or not, the United States and its allies have encouraged the internal fragmentation of the south, politically and administratively. They have directed their assistance directly to city- and town-level bodies, primarily the province’s more than seventy local administrative councils. Attempts to integrate the province at a regional, supra-local level have been frustrated or ignored. The Dara’a Provincial Council, for example, was long excluded from flows of international assistance because of Jordan’s discomfort with what it saw as the council’s links to the Muslim Brotherhood. The result is an atomized south—seventy-plus local entities held together by little real connective tissue.

The Syrian Media Organization’s Jebawi compared international support for civilian bodies to the MOC’s backing for the Southern Front. “States have relied on support for individuals, and small entities,” he told me. “They didn’t support hierarchical institutions.”22

Among the constraints the rebel south has faced is that it has tried, with its improvised administrative bodies, to approximate the traditional structures of the Syrian state, so as not to preclude their ultimate reintegration into a national government. There are fears that some unprecedented, specifically southern entity will contribute to the disintegration of the country.

“The less ambitious would say: This has worked so far. People get on with their lives, and things retain their labels in the national context,” said the same Western diplomat. “So, for example, you have a Provincial Council. Now the regime might not recognize it, but it’s not called something else—it’s not called ‘the Southern Council.’”23

“There were a number of attempts to produce a civilian leadership for the area,” said Jebawi. “But the obstacles were always fears that that would lead to secession.”24

The south needs a “Southern Council” of some sort: a credible, unitary leadership capable of negotiating opposite the regime.

But a divided south is not capable of speaking with one voice to the Assad regime. The south needs a “Southern Council” of some sort: a credible, unitary leadership capable of negotiating opposite the regime. Otherwise, the regime and its allies are going to pick off individual armed factions, towns, and clans one at a time.

“If you have seventy-plus entities of differing capabilities and constituencies and credibility, and without organization, you run a risk of the regime essentially—within the context of a calm situation—attempting incremental ‘reconciliation’ of these cantons,” said the anonymous diplomat. “So the task is to ensure that the overall opposition-held area is resilient to that attempt.”25

Cross-line trade and the continued provision of some government services from regime-held areas mean the regime has inroads into the rebel south, and rebels told me regime infiltration is real. The regime is already negotiating with representatives from some frontline towns,26 as are, according the Furqan Brigades’ Abbas, the Russians. The Russians “try to give the impression that they’re the guarantor, the king in the south,” he told me.27

The regime is primed to play on regionalism and local division to recapture the south piecemeal. “This is how the regime works,” Abbas said, sitting in an Amman apartment and gesturing to a square ashtray. “They deal with this side, and promise relief and detainees,” he said, pointing to one corner of the ashtray, before pointing to another corner—“so they can concentrate on this other side.”

The past year has seen various political-administrative initiatives to unify the south,28 but none seem to have gained much traction. Rebel backers need to just choose one leadership project and invest it with momentum and material support. Whether it’s some new project of regional integration or a move to genuinely empower the Dara’a Provincial Council in Nawa—the council held elections in March 2017,29 and under new president Ali Salkhadi it may be more palatable to the Jordanians—it doesn’t really matter. What matters is that the south is positioned to rejoin the Syrian state as a bloc, not as dozens of little, individually digestible pieces.

The answer is not linking the south with national-level opposition figures and bodies like Riyadh Hijab’s High Negotiating Committee, which have few real future prospects and which would entangle the south in the rest of the country’s unsolvable problems. The solution for the south is a southern one, and the south needs a single political champion to put opposite Damascus.

The alternative is the uncontrolled breakdown of the rebel south. That would be disastrous for southerners in human terms and, in strategic terms, for the interests of Washington and its regional allies.

Worth the Investment

The logic behind the southern de-escalation agreement and a specific U.S. focus on Syria’s southwest was and still is sound. The deal itself is worth pursuing, both because it has some chance of success on its own terms and because of how it intersects with compelling U.S. interests in the region. The agreement has some fairly evident vulnerabilities and weaknesses, but the ramifications of its collapse would be disastrous—a resumption of violence, destabilizing flows of refugees towards Jordan, and a new expansion of Iranian influence in Israel and Jordan’s backyard.

Shoring up the de-escalation will take work. Part of that work will be mental: American policymakers need to lean into a paradigm shift in America’s strategic outlook. They have to think less in terms of how to pit a rebel south against the Assad regime in an entirely hostile, adversarial dynamic, and more in terms of how to reorient U.S. involvement and America’s local partners towards a more sustainable relationship with Damascus. The objective is to earn the south some negotiated, limited autonomy under a regime-led state and satisfactorily maintain U.S. and allied influence. This sort of project will require some political sophistication, and maybe deference to Jordanian and Syrian partners who better understand how to navigate authoritarian politics. But at this point, this is the way to ensure the safety and well-being of the south’s residents and to ensure U.S. and allied equities.

Part of the work of saving the de-escalation is less theoretical—before December, someone needs to produce the money to pay rebel salaries. If the money stops and the south turns its guns inwards, maps and monitoring mechanisms negotiated in Amman won’t count for much.

And beyond that imminent December decision point, there is still an urgent need to define and lock in the politics of de-escalation, not just patch the ceasefire and open Nasib. The timetable on which America and its allies are working is not open-ended. The Assad regime will not indefinitely tolerate an insurgent-held enclave in a strategically vital corner of the country, even if it is now preoccupied on other fronts. And Russia will not be able to restrain the regime forever. The United States and its allies have to get ahead of that future regime offensive, while they still have the initiative.

America has washed its hands of most of Syria. But the southwest is at least one part of the country where America has some defined strategic interests and, with this de-escalation agreement, a half-plausible way of guaranteeing them. This de-escalation needs a proactive effort by the United States and its allies if it’s going to be saved—that effort seems worth it.

Notes

- Sam Heller, “America Had Already Lost Its Covert War in Syria—Now It’s Official,” The Century Foundation, July 21, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/america-already-lost-covert-war-syria-now-official/.

- “Press Briefing on the President’s Meetings at the G20 | July 7, 2017,” The White House, July 7, 2017, https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2017/07/07/press-briefing-presidents-meetings-g20-july-7-2017.

- “Background Briefing on the Ceasefire in Syria,” U.S. Department of State, July 7, 2017, https://www.state.gov/r/pa/prs/ps/2017/07/272433.htm.

- Donald Trump (@realDonaldTrump), Twitter, July 9, 2017, https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/884013689736769536.

- “Background Briefing on the Ceasefire in Syria,” U.S. Department of State.

- Diplomatic source familiar with the negotiations, author’s interview, 2017.

- Aron Lund, “Opening Soon: The Story of a Syrian-Jordanian Border Crossing,” The Century Foundation, September 7, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/opening-soon-story-syrian-jordanian-border-crossing/.

- Suleiman al-Khalidi, “Syrian rebels resist Jordan pressure to hand over border crossing,” Reuters, October 5, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-mideast-crisis-syria-jordan/syrian-rebels-resist-jordan-pressure-to-hand-over-border-crossing-idUSKBN1CA116.

- Sam Heller, “Geneva Peace Talks Won’t Solve Syria—So Why Have Them?” The Century Foundation, June 30, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/report/geneva-peace-talks-wont-solve-syria/.

- Western diplomat, author’s interview, 2017.

- Alaa Nassar, Waleed Khaled a-Noufal, Avery Edelman, “Daraa residents begin to repair homes as southern ceasefire holds,” SYRIA:direct, September 18, 2017, http://syriadirect.org/news/daraa-residents-begin-to-repair-homes-as-southern-syria-ceasefire-holds/.

- “Al-Ghouta al-Gharbiyyah: Al-Mu’aridah Tasudd Hujoumen ala Beit Jinn (West Ghouta: Opposition Repels Attack on Beit Jinn),” al-Modon, October 6, 2017, https://goo.gl/bZfKPF.

- Heller, “America Had Already Lost Its Covert War in Syria—Now It’s Official.”

- Ghazi Abbas, Furqan Brigades, author’s interview, Amman, Jordan, September 2017.

- Ibrahim al-Jebawi, Syrian Media Organization, author’s interview, Amman, Jordan, September 2017.

- Waleed Khaled a-Noufal, Ahmad Yassin, Mohammed al-Falouji, and Maria Nelson, “Daraa city rebels launch preemptive battle to hold onto Jordan border crossing,” SYRIA:direct, February 13, 2017, http://test.syriadirect.org/news/daraa-city-rebels-launch-pre-emptive-battle-to-hold-onto-jordan-border-crossing/.

- Western diplomat, author’s interview, 2017.

- Muhammad Ibrahim, “Al-Mukhaddirat Turawwaj fi Dara’a wa-Intisharha Yafouq al-Qudrah al-Mukafihah (Drugs Being Sold in Dara’a, Their Spread Exceeds Ability to Combat Them),” Enab Baladi, August 21, 2016, https://www.enabbaladi.net/archives/98974; “Al-Mu’aridah Tulahiq Murawwiji al-Mukhaddirat fi Dara’a (Opposition Pursues Drug Dealers in Dara’a),” Enab Baladi, September 14, 2017, https://www.enabbaladi.net/archives/172833.

- “Harb ‘al-Khutout al-Khalfiyyah’ fi Dara’a Lam Tatawaqqaf (War of ‘Rear Lines’ in Dara’a Goes on),” Enab Baladi, September 17, 2017, https://www.enabbaladi.net/archives/173167. For one of the latest assassinations, see “Maqtal Masoul al-Quwwah al-Tanfiziyyah li-‘Dar al-Adl’ fi Dara’a (Head of Dar al-Adl Executive Force in Dara’a Killed),” Enab Baladi, October 9, 2017, https://www.enabbaladi.net/archives/177173.

- Ali al-Maf’alani, Free Lawyers’ Syndicate, author’s interview, Amman, Jordan, September 2017.

- Madeline Edwards, Waleed Khaled a-Noufal, and Alaa Nassar, “Why is an Islamic State affiliate quietly ruling unchallenged in a corner of Syria’s south?” SYRIA:direct, September 28, 2017, http://syriadirect.org/news/why-is-an-islamic-state-affiliate-quietly-ruling-unchallenged-in-a-corner-of-syria%E2%80%99s-south/; “Hakaza Raddit ‘Hayat Tahrir al-Sham’ ala Mithaq ‘al-Jabhah al-Junoubiyyah’ (This Is How Hayat Tahrir al-Sham Responded to the Southern Front’s Charter),” al-Modon, August 11, 2017, https://goo.gl/5SqiLX.

- Jebawi, author’s interview.

- Western diplomat, author’s interview.

- Jebawi, author’s interview.

- Western diplomat, author’s interview.

- “‘Takhfif al-Tawattur’ Yuharrik Ajalat al-Musalihat fi Dara’a (De-escalation Moves the Wheel of Reconciliations in Dara’a),” Enab Baladi, October 1, 2017, https://www.enabbaladi.net/archives/175648.

- Abbas, author’s interview.

- For one, see “Tashkil Hayah Idariyyah fil-Junoub al-Souri li-Idarat al-Mantaqah (Administrative Body Formed in Syrian South to Administer the Region),” Zaman al-Wasl, August 10, 2017, https://www.zamanalwsl.net/news/80811.html.

- “Dara’a Tantakhib Raisan Jadidan li-Majlis al-Muhafazah (Dara’a Elects New Head for Provincial Council),” Kulluna Shuraka, March 22, 2017, http://www.all4syria.info/Archive/397096.