More than 14 million workers across the United States—carpenters, steelworkers, nurses, teachers, truck drivers, and many others—are union members, but rarely does one read how unions have improved workers’ jobs and lives.

There are plenty of stories about weeks-long strikes, hard-fought unionization drives, unions’ role in political campaigns, and unions fighting to raise the minimum wage. Perhaps it’s considered too prosaic, but there are hardly any stories that examine in depth how belonging to a union or joining a union has changed workers’ lives and improved things for their families.

This report takes a look at five workers—a construction worker, a barista, a charter school teacher, a forklift operator at a warehouse, and a hospital aide—and documents how belonging to a union has lifted those workers, has improved their pay and benefits, and given them a far stronger voice at work.

Laura Asher, Crane Operator

It was September 11, 2001, and Laura Asher was driving from her hometown in Indiana to her new college in upstate New York when she heard about the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center.

It was September 11, 2001, and Laura Asher was driving from her hometown in Indiana to her new college in upstate New York when she heard about the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center.

The following spring, as her freshman year was ending, she signed up for the Army National Guard—she was eager to serve her country, even if it meant leaving school. Besides, her father had warned her about accumulating a pile of college debt, and she realized that if she served in the military, the G.I. Bill would pay any future college tuition.

Asher, now age 38, served in Baghdad for a year as a combat medic during the Iraq War, working in ambulances and Medivac helicopters, often tending to the seriously wounded. After Baghdad, Asher returned to her hometown, Valparaiso, Indiana, and enrolled in courses to obtain certification to become a hospital aide. She became pregnant and gave birth to a son, raising him as a single mother because things didn’t work out between her and the father.

Being a mother persuaded her to quit the Army. “I had seen women in my unit, and their two-year-old children that they left didn’t even know who they were anymore.” As a single mother, Asher needed money, so instead of returning to college full-time, the former medic took a hospital job—as a phlebotomist, drawing blood and checking blood pressure. After three years at the hospital, her pay was $14 an hour, and her biggest headache was health insurance: she was paying $600 a month for premiums, $7,200 a year—one-fourth her annual income.

“Between health insurance and day care of $125 a week, there was no money for anything other than necessities like diapers and car insurance,” Asher said. “I wasn’t able to do the things you want to do for your children, like buying toys or going on vacation or going out to eat. I was just barely surviving.” The veteran moved back in with her parents, a humbling experience.

It was time to take a different path, she decided. So she pursued two opportunities—she applied for a union apprenticeship to become a crane operator, and she applied to nursing school, although she resented the prospect of having to relearn much of what she had learned to become a medic. Minutes after registering for nursing school, she was walking back to her car and received a phone call—it was good news, the International Union of Operating Engineers was calling to say she had been accepted into the union’s apprenticeship program to become a crane operator. “The [union’s] helmets to hardhats program was how I got in,” Asher said. She withdrew from nursing school, without ever attending.

There were twenty-two apprentices in her crane program; just two of them were women. “I had been in the Army. I know how to deal with this,” she said. “I love a challenge.”

As soon as she began that apprenticeship back in 2011—it was run by the Operating Engineers—she was paid $19 an hour, with her compensation increasing each of the apprenticeship’s four years. “Within eight months, I was able to move out of my parents’ house with my son, and into my own apartment,” Asher said. “I wasn’t just providing for him. We were thriving. It wasn’t just macaroni and cheese and driving a beater.”

Mother and son took a beach vacation in South Carolina; they went to Disney World. “We were doing well. That’s the dream.”

In her apprenticeship, which was conducted under close union supervision, Asher spent hundreds of hours learning how to operate different kinds of cranes: for road construction, building office towers, repairing factories, and more. “There’s an old saying in the Operating Engineers: you feel it in your fanny,” she said. Asher has operated cranes that are twenty stories high and has become so expert that she now teaches some apprenticeship classes.

“When I get into the seat and start operating, they recognize this is not some girl. She knows her shit. She is good at the machine,” Asher said proudly. “I hold myself to a high standard and will outwork any man.”

In her current job, Asher operates a crane at the giant Cleveland-Cliffs steel mill (formerly ArcelorMittal) just east of Gary, Indiana, moving materials and equipment to repair the super-hot ovens that produce coke, a fuel used to make steel. Thanks to the union’s contract, her take home pay is $44.25 an hour, just under $1,800 for a forty-hour week—and that $44.25 is after deductions for her health care premiums and pension.

Asher now owns a house on five acres in the country, a far cry from living with her parents. She leaves home at 4:15 a.m. and works from 5:30 to 2:30. She is usually home by 3:30, and is grateful that she can see most of her son, Colin’s, games. Now in seventh grade, Colin plays football, baseball, and basketball. “I’m his biggest fan,” she said.

“The union has changed my life and given me opportunities to better myself,” Asher said. “I have the ability to show my child what you can do in adversity. Through hard work and the opportunities that come along, you can be anything that you want, you can climb as high as you want. It’s beautiful. The example I’m setting for my son I hope will run down my line for generations to come.”

Gregory Swanson, English Teacher

Gregory Swanson is not your typical teacher. At age 51, he has shoulder-length hair and is known for high-fiving students. One of his school’s most popular teachers, he teaches five advanced placement English classes, all to seniors, at Benjamin Franklin High School in New Orleans.

Gregory Swanson is not your typical teacher. At age 51, he has shoulder-length hair and is known for high-fiving students. One of his school’s most popular teachers, he teaches five advanced placement English classes, all to seniors, at Benjamin Franklin High School in New Orleans.

To this day, Swanson remembers a tense exchange he had a decade ago when he applied to teach English at Benjamin Franklin, a magnet school widely considered New Orleans’ best high school. The school’s CEO told Swanson, “We have three equally qualified candidates, and we’re in a budget crunch, so would you be willing to work for this?” The school’s CEO slid a piece of paper to Swanson that had a low-ball salary number on it.

Swanson responded, “I’ll work for whatever is on the pay scale you have.” He hoped that, having taught for eleven years, he would be paid what the pay scale set for a teacher with eleven years’ experience.

“But he said, ‘I decide what you’ll make,’” Swanson recalled.

After Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans in 2005 and its schools were closed temporarily, the city’s school board fired all 4,300 public school teachers. That was widely seen as a move not just to save money, but to destroy the city’s teachers’ union. The city subsequently opened its public schools as nonunion charter schools.

Swanson took the job at Ben Franklin, but he’s still peeved about what happened with his salary. “There was no clarity or equity in the pay scale,” Swanson said. “He started me at the pay scale of a fourth-year teacher when I was an eleventh-year teacher. I think he did that more to women than to men.” Swanson said he accepted that low-ball salary because he badly needed a job. He had just moved back to the United States after teaching in Brazil.

“Back then, we had an absolutely terrible administration that wasn’t treating people well,” he said. The school’s CEO had fired a popular gym teacher who had coached Ben Franklin’s volleyball team to 500 wins. “They treated other teachers absolutely horribly, especially the beloved Latin teacher, Dr. Pierce,” Swanson said. “He was a wonderful man.”

Eager to improve matters, Swanson led a unionization drive that got 85 percent of the school’s teachers to sign a pro-union petition. With strong support from parents and students, the teachers pressured Ben Franklin’s board into recognizing the union, which is part of the American Federation of Teachers. Ben Franklin became the first New Orleans school, post-Katrina, to have a union contract.

The contract calls for teachers to be paid according to their years of experience. For Swanson, that meant a raise of about $8,000, nearly 20 percent. “It was a huge change for us, having some transparency around pay,” he said.

“The vibe of the school had been really negative,” he added. “I really feel that having a voice in the school has made a big difference. Having some fairness in how we’re treated and having some job security also make a real difference.”

In those first contract negotiations, the school surprisingly agreed to grant tenure to teachers after two years, making it the first New Orleans school to offer such job security post-Katrina. “We got tenure after two years, it was mind-boggling,” Swanson said. Teachers can still be fired, but only after due process procedures that can include an arbitration hearing.

Before the union, Swanson taught 150 students in multiple AP classes. “Now, in our most recent contract,” he explained, “they can’t give us more than 130 students to teach, and for each student above that, they have to pay you extra.”

That first contract gave teachers a prep period each day and called for teachers to elect their department chair. It also created a labor–management committee of three teachers and three administrators to solve problems together. “We teach this to new administrators: having the union is not combative—of course, contract negotiations are—because we work together. We can help you solve problems.”

Swanson has a message to teachers in New Orleans and beyond: “It’s worth the risk, it’s worth the fight to have a union,” he said. “Having a union makes the school better. Some schools have a terrible problem of turnover. Having a union reduces turnover. People want to work here because we have a union. You get more quality people.”

“It is unique what we’ve gotten here,” Swanson continued. “It sets a standard for what other schools in New Orleans can achieve in terms of getting voice, fairness, transparency, and job security.”

Madeleine Souza-Rivera, Barista

“I’ve been in food all my life,” said Madeleine Souza-Rivera, a 33-year-old California native. At age 16, she went to work at a Cold Stone Creamery in Fremont, her hometown, and after high school, she took a job at a bakery in Los Angeles. Next, she became a hostess at Outback Steakhouse, and later a barista back in Fremont.

“I’ve been in food all my life,” said Madeleine Souza-Rivera, a 33-year-old California native. At age 16, she went to work at a Cold Stone Creamery in Fremont, her hometown, and after high school, she took a job at a bakery in Los Angeles. Next, she became a hostess at Outback Steakhouse, and later a barista back in Fremont.

A friend’s father told her of a better-paying barista job at Google, and she leapt at the opportunity, taking a $14-an-hour job at a café inside Google’s headquarters. She liked the job, but there was a huge drawback—the health plan. After she gave birth to a son in 2018, her health premiums climbed to $800 per month, $9,600 a year—one-third of her take-home pay. “That hurt,” Souza-Rivera said. “I was happy where I worked, but I knew deep down it would be better if we had a union.”

One day in 2018, she heard a few coworkers discussing a union, and she was interested. She attended a meeting with union organizers and quickly became enthusiastic about having a union. “It was the sense of community,” she said. “It was the positive vibe.” Before long she was asking coworkers to sign cards backing a union, and that sometimes took convincing. “A lot of people when they hear ’union,’ they’re afraid that they’re going to get in trouble,” she said.

At the time, Souza-Rivera and some 2,300 baristas, cooks, dishwashers, and other food workers at Google worked not directly for Google, but for Compass Group, a contractor. Compass granted union recognition in December 2019 after the vast majority of workers signed cards saying they wanted to join Unite Here, the hotel and restaurant workers’ union. Once a union contract was signed, most workers received a 25 percent raise, usually ranging from $3.60 to $5 an hour.

“I was making $14 an hour, now I’m making $27 an hour,” Souza-Rivera said. Her pay has soared partly because of raises the union bargained for, partly because she was promoted to supervisor, and partly because Google and Compass increased pay to help with Silicon Valley’s high living costs. As a supervisor, Souza-Rivera now oversees a small team of baristas at her café, the Fresh Market Café, inside the Google complex in Sunnyvale.

“Now I pay nothing for health,” she said—probably her favorite part of the union contract. Moreover, she has a platinum health plan, better than her previous plan.

When Souza-Rivera first considered a union, her focus was on better pay and health coverage. “Pensions weren’t even a thought, and we ended up getting that,” she said. The union’s contract calls for Compass to contribute $3 per hour toward a pension, meaning $6,000 per year for a full-time worker. What’s more, the company matches 30 percent of employees’ 401(k) contributions. Not only that, because the Silicon Valley area is expensive to live in, Compass and Google—pushed by Unite Here—increased the housing and transportation subsidy to $400 a month.

“It’s awesome,” Souza-Rivera said about having a union.

The union contract also doubled the number of paid sick days workers receive to six a year. It further gave workers two weeks’ paid vacation in their first year, four weeks’ vacation after five years on the job, and six weeks after twenty years.

She praised the union’s role during the pandemic. “It kept me in the loop, I wasn’t left in the dark.” She said that, together, Compass, Google, and the union did a terrific job ensuring that workers would maintain their job security and continue being paid during the pandemic, even when Google’s offices, cafés, and cafeterias were closed.

One side benefit of her job was that Souza-Rivera met her husband-to-be, Francisco, at Google, where he was a dishwasher. She began working at Google one August and met Francisco another August, and that inspired them to name their son August. “We’re able to save money for him,” she said. “I don’t think we would have been able to unless we had free health care. Money gets put in his savings so when he’s old enough, he’ll be able to have something for himself.”

She talks excitedly about taking three-year-old August to union rallies. “I show him that we have a voice, letting him know he has a voice.” They have also taken August to Disneyland and Lake Tahoe—vacations she could hardly have dreamt of while paying $9,600 a year in health premiums.

As a union steward, the once-diffident Souza-Rivera often speaks to groups of workers to explain the details of their health plan. “The union really helped build up my confidence and trust in myself,” she said.

Souza-Rivera has heard the anti-union criticisms about how onerous union dues supposedly are. “The dues are nothing to me,” she said. “I don’t even notice it.” Asked how she sees the role of unions, Souza-Rivera responded: “A union is there to make sure that you’re not being walked all over and that you’re taken care of, to make sure that your job is one worth having, that you’re going to have good health care, to make sure you’re not treated badly.”

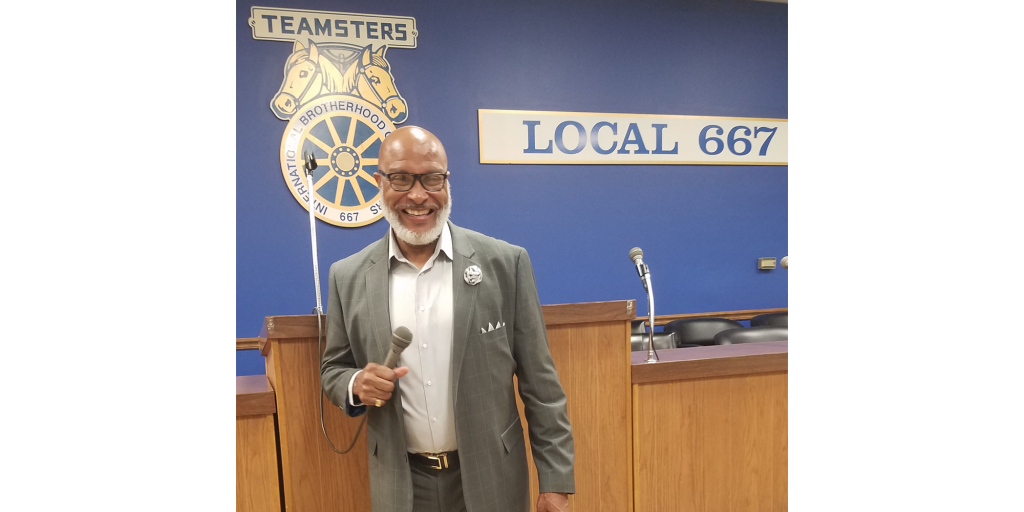

Donnell Jefferson, Warehouse Worker

Donnell Jefferson isn’t shy about boasting that as a unionized warehouse worker, he earns far more than workers at Amazon’s warehouses. “I’m at $29.30 an hour, and many of them are at $16 a hour,” said Jefferson, a 59-year-old forklift driver at a T-Force warehouse in Memphis. “Our pay is way above theirs.”

Donnell Jefferson isn’t shy about boasting that as a unionized warehouse worker, he earns far more than workers at Amazon’s warehouses. “I’m at $29.30 an hour, and many of them are at $16 a hour,” said Jefferson, a 59-year-old forklift driver at a T-Force warehouse in Memphis. “Our pay is way above theirs.”

Jefferson, a member of the Teamsters, was working at T-Force’s predecessor company, Overnite Transportation, when he saw up close the ups and downs of unionism. A year after he began at Overnite, the Teamsters staged a grueling, sometimes violent three-year strike against Overnite, from 1999 to 2002, trying to get it to agree to a first union contract. The Teamsters lost that showdown, ending the strike without a contract.

United Parcel Service acquired Overnite in 2005, and Jefferson plunged into a new Teamsters’ effort to unionize Overnite, which was renamed UPS Freight. That effort was successful. Early this year, UPS Freight was acquired by T-Force.

“I was making $16 an hour, and when we got that first union contract, we got a $4 raise,” said Jefferson. “That was like getting an additional part-time job.”

“Our health benefits also changed. I was paying close to $300 a month for family health benefits,” said Jefferson, who has six children. “Now I pay close to $150.” That translates into savings of around $1,800 a year.

“It [the union] made a tremendous difference,” he said. “We were living at that time in a three-bedroom house. After we got that raise, we moved to a five-bedroom house. Once I got that raise, things changed. It keeps a smile on my wife’s face. She was happy, but it seems her smile has gotten bigger.”

Jefferson praises his health and drug benefits. “If I have to get any type of medication, I’m not going to pay anything over $3. I may pay 37 cents for some medicine. The ladies working at CVS say, ‘You’re lucky. I haven’t seen anyone who pays just 37 cents.’ I’m a diabetic, I pay like $2.50 for Metformin,” a diabetes medicine.

Jefferson recently volunteered to work on the Teamsters’ promised push to try to unionize Amazon warehouses. Jefferson has a young cousin who works at Amazon and often calls to ask him for a loan, causing Jefferson to ask why Amazon doesn’t pay its workers enough to live on. “As big as Amazon is, you would think they would allow the money to trickle down to the actual employees who are doing the work. It’s like Jeff Bezos and his buddies just want to keep the money to themselves and see how rich they can get. Someone did a study showing that if Bezos gave every Amazon employee $105,000 apiece, he’d have the same amount of money [overall wealth] as at the beginning of the pandemic.”

In Jefferson’s eyes, one of the biggest advantages of having a union is that it has assured better treatment from management. “Back in the day when we were Overnite, we didn’t have any say on anything. It was, ‘Do what we say or I’ll show you the door.’ Now that we’re unionized, we have a voice. If the company is not doing what they’re supposed to do, we have people to stop them.”

He recalled that a manager once sought to fire him, accusing him of talking about union matters for five minutes during work time. “The union came down to rectify things,” Jefferson said. “They said I was talking for only 30 seconds.” The union’s help, he said, kept him from getting fired.

Jefferson is no stranger to talking union. He grew up in Chicago, where his father worked at a unionized Nabisco factory. “He loved the union because he was very boisterous. They [the managers] would always be on him.”

Jefferson said that he, too, has had his share of nasty bosses. “We used to have a supervisor when we were Overnite who used to walk around with our time cards in his back pocket. He would tell us when we could or could not go home, regardless of whether we had an emergency. Some of the guys would come to work to pick up their check, they’d be dressed in a shirt with a collar, and he’d tell them that they had to break a load off a trailer before they got their check.”

“One reason we wanted a union,” Jefferson continued, “was we knew what time we had to be at work, but we never knew when we were going home. It could be eight hours, or they’d say we had to work sixteen hours.”

Now he has a work schedule that is more reliable and a job that is more rewarding.

Lorie Quinn, Hospital Housekeeper

Looking back, Lorie Quinn can now laugh about what happened at that anti-union meeting, where her hospital’s CEO told fifty or so workers that the hospital is one big family, that if you need something, just ask us, and that you’re not allowed to talk about the union at work.

Looking back, Lorie Quinn can now laugh about what happened at that anti-union meeting, where her hospital’s CEO told fifty or so workers that the hospital is one big family, that if you need something, just ask us, and that you’re not allowed to talk about the union at work.

Quinn and two pro-union coworkers stood up and loudly interrupted, “That’s incorrect. That’s protected by law”—referring to talking about the union. “It was a really fun time to put the CEO in their place,” said Quinn, a hospital housekeeper who cleans intensive care units. “Before we started getting a union and getting a backbone, would you ever talk to the CEO like that?”

That meeting was in 2015, and not long after, housekeepers, cooks, certified nursing assistants, and other frontline workers at her hospital—PeaceHealth Sacred Heart Hospital in Eugene, Oregon—voted 524 to 367 to join the Service Employees International Union.

Quinn, an enthusiastic, talkative 53-year-old, said that the union won, notwithstanding the hospital’s big anti-union push, because workers were unhappy on so many levels. After three years at PeaceHealth, “I was still in the $10-not-quite-$11 range,” Quinn said. “You can’t live on that. You have to take two jobs.” Quinn, who worked a second job at a quilting shop, was appalled that so many PeaceHealth employees were on food stamps.

She complained that there was a lot of favoritism in how much workers were paid. “It’s all up to the manager what your wages were,” she said. “It wasn’t fair.” All too often, she quipped, “your raise was directly related to your bust size.”

The hospital’s health care plan was so expensive that many workers signed up instead for Oregon’s Obamacare plan. “Oh my God, they’re working for a hospital and they’re needing health insurance from the state,” she said. Quinn, who has two children and a disabled husband, said that her family health insurance premiums totaled about $2,400 a year before unionization, but have since dropped to half that with the union.

Many workers were angry that PeaceHealth often garnished employees’ wages for medical services they had received from the hospital. “This happened time after time,” Quinn said. “I was shocked that our employer was taking huge amounts out of their checks.”

Quinn said the hospital made it hard to schedule vacations—“you had to get people to cover for you.” She also pointed to problems with sick days—“you could only call out or be sick three times in a rolling six-month period.” For workers with children who often got sick, that rule often jeopardized their jobs.

Unionization brought big and welcome changes, Quinn said. She now earns $18.12 an hour, up around 70 percent since 2015. “Now we have a wage scale. We know we get two raises a year. We know what those are going to be and when they’re going to happen. Before it was just if management wanted to do it.” After the union was voted in, the hospital stopped garnishing employees’ wages and made it easier to take vacations and sick days.

Before unionization, Quinn wasn’t able to save money. Now, she said, “it’s amazing. I was able to get all my credit cards paid off”—some $1,500 in debt she had previously kept rolling over and paying high interest on. Not only that, she was able to save enough money to take a two-week vacation to Ireland.

“My main thing was wages. The second thing was respect from management. Before, you had to do whatever they said. You had to do it without having an opinion about it. . . . You couldn’t go to them and feel you’ve been listened to.”

Quinn has seen welcome changes on that front. She’s now a union representative on the hospital’s labor–management committee. “We have a meeting, and I’m not so much a housekeeper. I’m a union member. I’m treated like more of an equal.”

“It’s nice they listen to you. It’s nice they listen to workers down on the floor doing the work. It’s good they’re listening to what it means to be a worker.” Previously, she said, management had little idea how burdensome health care premiums were for $10-an-hour workers. One outgrowth of the hospital’s increased listening to workers, Quinn said, is that it has created a premium assistance program for workers who were paying a disproportionate amount of their income toward health premiums.

Quinn, who has studied up on workers’ rights, bridled when the CEO and other executives insisted that PeaceHealth’s employees couldn’t talk about the union. “If you can talk about your kids and football games at work, you can also talk about the union,” Quinn said. “Workers have rights. That’s something that many people don’t know, that you as a worker have a right to organize a union and talk about it at work.”

“I do have a voice,” Quinn continued. “I am learning what I can do and can’t do—and need to do. I’m encouraging my coworkers to be strong, too.”