These are dark times for labor. The Republican majority that now controls all levels of the federal government has made it clear that they plan on rolling back labor and employment protections, while also not funding and enforcing the currently existing laws. Judicial conservatives have regained their fifth vote on the Supreme Court and a new case challenging the constitutionality of public sector fair share agreements is at the Court’s footsteps.1 House conservatives have introduced a national right-to-work amendment to the National Labor Relations Act of 1935 (NLRA), and other restrictions on union activity are likely to be moved in the House.2 All of this will come at a time when the power and reach of organized labor is at historic lows.

Today, less than 11 percent of workers in America are members of a union, including 6.4 percent of private sector workers and 34.4 percent of public sector workers.3 The dramatic drop in union representation since the 1950s, when over a third of the workforce was unionized, has resulted in stunning income inequality, wage stagnation, continued wage discrimination against women, tens of millions of Americans working for sub-poverty-level wages, and widespread gaps in basic health, retirement, and family leave benefits.4

Traditionally, the courts have not been kind to labor. From the very beginning of our nation’s history, the earliest union efforts were treated by conservative jurists as criminal conspiracies and interferences with employers’ property and contract rights and with Congress’ responsibility to regulate interstate commerce. Unions spent the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries decrying “judge-made law” and seeking, essentially, to get the government and courts out of labor disputes.

For a brief time this worked. The Norris-LaGuardia Act of 1932 sought to prevent the federal courts’ military from enjoining or interfering in union protest activity, and many states passed similar laws to keep their courts and police out of the fray. The NLRA made it the official policy of the United States to encourage the practice of collective bargaining. The Act established a federal agency, the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), that would certify the existence of a union at a workplace and sanction employers who refused to deal with a bona fide union.

Much of the thrust of mid-century labor law was to encourage a private system of jurisprudence: contract negotiations, arbitration and the occasional industrial warfare of strikes, boycotts (and, later, lockouts). Though unions point proudly at the legislative and regulatory successes they have achieved since the 19th century, they retain a vestigial bias against legislating and litigating our rights and benefits.

Unfortunately, labor rights have been gutted by bad court decisions and worse legislative action. The courts pretty quickly waved away legal job protections for striking workers (particularly for those who engage in what had been unions’ greatest strategic weapon in the 1930’s: the sit-down strike), have granted employers wide “free speech” latitude to conduct campaigns of terror to break their employees’ resolve to form unions and have removed large categories of workers from protection under the Act.

Pro-union labor law reform has been largely unachievable since the passage of the NLRA in 1935, and Congress has instead twice amended the NLRA to severely restrict unions’ ability to engage in solidarity activism in the form of boycotts and sympathy strikes, to protect and enforce union shop agreements and to enhance employers’ rights to fight back against their workers’ demands for a better quality of work life. In more recent years, Congress has severely underfunded the NLRB, cutting agency staff and essentially giving employers wider latitude to break the law with impunity.

Simply put, unions are hampered by rules that would never be applied to corporations, or to any other form of political activism.

Simply put, unions are hampered by rules that would never be applied to corporations, or to any other form of political activism. One of the root causes of this injustice was a conscious decision by the framers of the NLRA to root its constitutional authority in the Commerce clause—not in the First Amendment right of free speech and assembly, nor in the Thirteenth Amendment right to be free from “involuntary servitude.”

As Rutgers law professor James Gray Pope has detailed, tying the NLRA to the Commerce clause was a conscious, “pragmatic” decision of progressive lawyers to reject a half-century of a rights-based campaign for labor law waged by the American Federation of Labor.5

The decision is not just a historical footnote. It has the perverse effect of judging worker rights—which are human rights concerns—within the frame of impact on business, to the exclusion of free speech and other considerations. The last half-century has demonstrated that, in such a framework, the courts will tend to have more sympathy for business interests.

Labor rights are rooted in fundamental constitutional rights—from First Amendment freedoms of speech and association to Fifth Amendment protections from unlawful takings to Thirteenth Amendment freedoms from involuntary servitude. However, there has grown a trend whereby labor’s foes have perversely used these constitutional rights against labor. This is seen most often in the push for so-called “right-to-work,” that prevents unions from collecting fair-share fees to cover the expenses germane to collective bargaining.

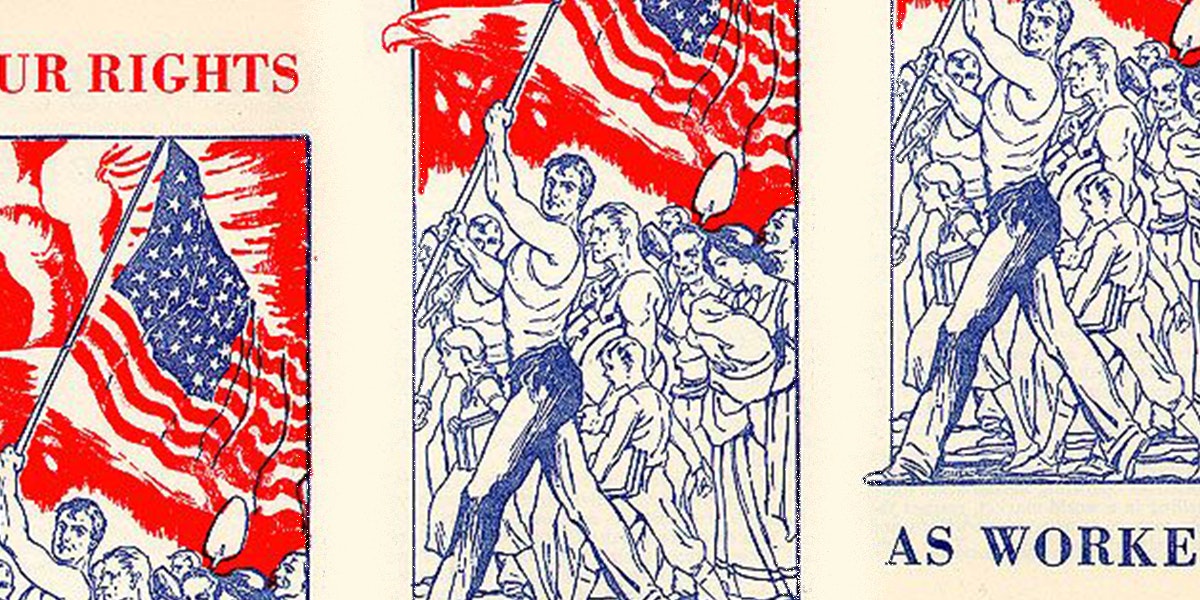

It is the time for unions and their allies to return to the rights-based rhetoric and constitutional legal strategies that preceded the passage of the National Labor Relations Act and the development of our current labor law regime. The rights of working people to unite, to protest, to withhold their labor, to boycott unfair businesses, and to demand change in all areas of business and society precede and transcend individual labor statutes. Our rights are fundamentally rooted in the Bill of Rights and the Reconstruction amendments. Where the labor law regime, through statute or judicial fiat, restrict our constitutional rights, it should be resisted and challenged as such.

This report will outline the below ten rights which, together, constitute Labor’s Bill of Rights:

- The Right to Free Speech

- The Right to Self Defense and Mutual Aid

- The Right to Strike

- The Right to Organize Free from Unreasonable Search and Seizure

- The Freedom From Taking Away Union Fees

- The Right to Not Be Locked Out for Exercising Labor Rights

- The Right to a Job

- Freedom from Cruel and Unusual Regulation

- The Right to Make Demands and Bargain Freely

- Powers Not Exercised by Unions Are Reserved to Workers Who Act in Concert

Labor’s First Right: The Right to Free Speech

Over the course of a few weeks in 1949, ten unionized technicians at the Jefferson Standard Broadcasting Company distributed handbills criticizing their employer. The workers were in the middle of protracted negotiations and had been without a contract for some time. The Charlotte, North Carolina company was one of the first television broadcasters in the country. The handbills criticized the company’s substandard technical equipment and lack of local programming, and charged that Jefferson Standard considered Charlotte a “second class city.”6

They were swiftly fired. The workers filed an unfair labor practice charge at the NLRB, arguing that they were participating in what they considered to be legally protected concerted activity to advance their contract campaign. The NLRB disagreed, and ruled that the technicians’ actions were not protected, because they were not obviously and explicitly connected to the union contract campaign. Upon appeal, the U.S. Supreme Court issued Labor Board v. Electrical Workers (Jefferson Standard)—one of the most anti-free speech decisions in the realm of labor law that thundered, “there is no more elemental cause for discharge of an employee than disloyalty to his employer,”7 henceforth known as the Jefferson Standard dictum.

Interpretation of Jefferson Standard has for decades led to a hash of confusing and contradictory NLRB and appellate court decisions, which continue to chill the rights of workers to speak out about their workplace.8 The idea that union activists can be fired for making what employers consider “disloyal” statements about their employer seriously undermines organizing campaigns, and is used as a tactic by union-busting firms to delay and derail legitimate organizing activities.

In Jefferson Standard, an arm of the federal government (the NLRB) declined to enforce workers’ statutory protections based on the content of those workers’ speech. Such a decision in any other realm would not pass constitutional muster; it should not in the workplace, either.

This truth should be self-evident, despite how contradictory it is to so much current labor law: working people do not shed their free speech rights simply because they desire to join together as a labor union.

How to Restore This Right

To restore this right, unions and their allies must raise more First Amendment challenges to the labor law regime. Unions, worker centers, individual workers, and law firms could—and should—challenge any governmental restriction on workers’ pure and simple words. If a flyer, tweet, or online post, in and of itself, is challenged by a government agency to violate the Taft-Hartley Act, a state labor law, or some obscure and ill-considered court decision, mounting a First Amendment challenge must become a primary strategic consideration.

Ironically, one area of labor law where the courts often consider free speech in the realm of labor is with regard to the employer’s speech rights.9 For instance, the Supreme Court has taken free speech into consideration in carving out an employer’s right to conduct captive-audience meetings. Employers use these mandatory meetings—held in all-staff, small-group, or one-on-one formats—to “educate” employees about the disadvantages of unionization, but they are really designed to confuse and intimidate employees into voting against union representation.

In a 2009 study, 10 Kate Bronfenbrenner, director of research at Cornell University’s School of Industrial and Labor Relations, found that nine out of ten employers utilize captive-audience meetings to fight union organizing drives. Employers threaten to cut wages and benefits in 47 percent of documented cases, and to go out of business entirely in a staggering 57 percent of cases. Unions win only 43 percent of certification elections when employers run captive-audience meetings (as opposed to an overall win rate of 55 percent).11 No wonder union avoidance consultants consider it “management’s most important weapon in a campaign.”12

A fair application of the First Amendment would embrace the principle of “equal time” in mandatory presentations about the pros and cons of voting for a union in an election conducted by a government agency. For the government to grant employers a right to force employees to attend a “vote no” presentation, but grant no such right to “vote yes” advocates to respond to the lies, half-truths, and threats that are presented is an obvious and shameful violation of workers’ First Amendment rights.

A group of 106 leading labor scholars, led by Southern Methodist University law professor Charles Morris and Marquette University law professor Paul Secunda, have filed a rulemaking petition at the NLRB to re-establish an equal time rule (which was the NLRB standard for a brief time in the 1950s). This petition is a good start, but unions should press the matter further, into the courts to establish a clear constitutional right to be free from the one-sidedness of captive-audience meetings.13

Challenging the one-sided approach to captive-audience meetings at the NLRB and in the courts will serve to highlight the unfairness that workers face when trying to organize a union, and could lead to more even-handed union elections, more consistent with the purposes of the NLRA.

Labor’s Second Right: The Right to Self Defense and Mutual Aid

On a hot summer day in 1996, a sixteen-year-old tomato picker named Edgar in Immokalee County, Florida, was beaten bloody by a straw boss when he had the nerve to take a water break.14 The bloodied shirt that Edgar had worn came to represent the abuse these workers faced, as organizers literally waved it at a rally to galvanize the Coalition of Immokalee Workers (CIW) to stand up against the privations of nonunion farm work. The shirt became a symbol of their resistance.

The CIW movement eventually led to nationwide boycotts against fast food restaurants such as Taco Bell and McDonalds, who purchased the Immokalee-grown tomatoes in bulk, at “bargain basement prices.”15 The boycotts were only lifted when those companies agreed to purchase tomatoes exclusively from growers who followed a list of rules that had been established by the Coalition, which included access to drinking water, tents for shade, health and safety committees, and a one-penny-per-pound pay increase for the workers.

The CIW campaign of rallies and boycotts was a success, and has clearly raised the working and living standards for the Immokalee workers. It should serve as a model for other labor organizations, except for the fact that, under the National Labor Relations Act, it would be illegal for a union to carry out such a campaign.

Labor’s core principal and best defense is the practice of solidarity. One of the oldest slogans in the labor movement, coined by the Knights of Labor shortly after the Civil War, is “An injury to one is the concern of all.” Unions are organized on this principle.

Yet, our labor law has long prohibited such concerted activities, ignoring that working people have a right to self-defense when it comes to protecting and improving their working conditions. The current labor law regime makes it illegal for unions and workers to extend solidarity in the form of strikes and boycotts beyond the organizational boundaries of their immediate employer, and punishes transgressions with crippling fines and injunctions. American labor law essentially requires union members to cross other workers’ picket lines, or face punishment.

Imagine a truck driver refusing to make a delivery to a grocery store where the workers were on strike. Imagine grocery store workers refusing to stock a brand of cookies on the shelves, because the cookie company shut down a unionized factory and shipped those jobs overseas. Imagine workers at an industrial laundry facility refusing to clean bed sheets that come from a hotel where the workers are locked out, or a hotel’s room attendants refusing to make beds with linen that comes from a facility that is involved in a labor dispute.

Such solidarity activism is an essential component of trade unionism. It is carried out by unions around the world. Workers who are organized at such strategic positions in the economy would have the power to help nonunion workers get organized and recognized, and be a strong bulwark against union-busting and off-shoring.

The potential power of such solidarity actions is obvious—which is why it is currently illegal. And unlike much of the program required to reverse anti-union judicial activism and establish labor’s rights, recognizing the right to self defense and mutual aid faces the high hurdle of reversing two amendments that Congress has made to the National Labor Relations Act to restrict workers’ freedom to make common cause.

The 1947 Taft-Hartley amendments made it an Unfair Labor Practice (ULP) for union members to boycott or picket a “secondary” employer—that is, a company that they do not work directly for, but who has significant or even essential business dealings with their employer, with whom they do have a contractual dispute. The 1959 Landrum-Griffin amendments tightened those restrictions further, and even made it illegal for a union and an employer to agree to contract language that frees members to choose not to touch “hot cargo” (products of another company where there is a labor dispute).

Legislative prohibitions on solidarity activism treat workers and consumers as if they are competing interest groups (rather than two halves of the same person), and then exploit the frustration of consumers from becoming embroiled in industrial disputes over which they feel they have no obvious decision-making power. But corporations engage in secondary disputes all the time, without penalty. How many television consumers have seen entire channels blacked out, replaced with the name and number of a corporate CEO to call and complain to, simply because the cable provider did not want to pay the rate increase from the corporate owners of the blacked out network? Cable companies have mastered the art of the secondary boycott, using their strategic position to leave television consumers in the dark, as they have few alternatives to their local cable providers. Why is the use of the secondary boycott legal when employed by media companies, but illegal when exercised in solidarity by workers?

Therefore, at the heart of a movement to restore the right to solidarity activism must be an equal protection argument. If corporations—which, I am told, are persons—get to enjoy an economic right that many people, in the form of unions, are denied, then that is a violation of working people’s and unions’ Fourteenth Amendment rights.

How to Restore This Right

One place to start in regaining labor’s right to self-defense is the excessive restrictions on so-called signal picketing. Signal picketing is accomplished through demonstrations that involve hand billing and unique visual protests, such as giant inflatable rats. Signal picketing is meant to call out and embarrass unfair employers, but is not an explicit call for a boycott. Signal picketing should be protected free speech activity—except the courts have drawn on bad stereotypes of labor shake-downs, ruling that when unions engage in this sort of educational picketing, they are signalling that anyone crossing the line will face physical harm.

The twenty-first-century reality, however, is that informational picketing is as likely to be carried out by members of a worker center such as CIW, student labor activists, Jobs with Justice chapters,16 or any other interested community activist—none of whom are union staff or even union members—than by a union covertly picketing for recognition. Furthermore, too few people in this country have grown up in union households where they were admonished to never cross a picket line, so, to whom is this a signal, and what is it telling them to do? Whatever fantasies previous justices had about the physical threats implied in an informational picket are clearly a relic. The current reality is that a ban on signal picketing is a clear violation of workers’ First and Fourteenth Amendment rights.

The physical act of picketing is clearly a demonstration of free speech. So, building upon a First Amendment affirmation of the legality of informational picketing, why is it constrained by bad law and judicial fiat when it is for union recognition? And, while courts in the post-NLRA era have ruled that the exercise of speech and economic pressure can act as constraints on commerce and therefore can be restricted, there is also a comparable amount of prior time and case law in which unions argued that the Thirteenth Amendment’s protections from “involuntary servitude” justified collective worker action against the dictates of large corporations.

It is worth noting that the sponsor of the NLRA, Senator Robert Wagner, in justifying his bill, said that “We are forced to recognize the futility of pretending that there is equality of freedom when a single workman, with only his job between his family and ruin, sits down to draw a contract of employment with a representative of a tremendous organization having thousands of workers at its call.”17 Unfortunately, as Rutgers law professor James Gray Pope details,18 Wagner rooted his law in the Commerce Clause and, once the Supreme Court upheld it, unions virtually abandoned the Thirteenth Amendment as labor law. The time is ripe for unions to return to this amendment as a justification of speech plus economic pressure.

University of Texas law professor Julius Getman writes extensively on the courts’ free speech double standard.19 Noxious hate groups such as the Ku Klux Klan and Westboro Baptist Church have seen their picketing and boycotts vigorously defended by the courts, while unions, judged instead by the impact on commerce, have had even purely political boycotts enjoined.20

Getman reminds readers that the International Longshoremen’s Association protested the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan by refusing to load or unload cargo meant for Soviet ports. Even though there was no material gain for the union, and companies and workers in foreign lands do not fit the NLRA’s intended definition of “employers” and “employees,” the boycott was enjoined.

But that was four decades ago, and the Supreme Court has spent the time between in an uneven expansion of the First Amendment—all on the side of business interests. Bold unions, particularly at the ports, could push the envelope with more politically motivated boycotts and push back on sanctions by arguing that the NLRB does not have jurisdiction over a dispute with a foreign government and that the workers have a free speech right to engage in the boycott. With democracy imperiled in countries like Turkey and Brazil (to name just two), and, with it, workers’ rights and protections, there are no shortage of opportunities for global solidarity and free speech.

Labor’s Third Right: The Right to Strike

On a cloudy afternoon in April of 2006, Roger Toussaint led a procession of union members across the Brooklyn Bridge. Toussaint—the president of Transport Workers Union Local 100 and an immigrant from Trinidad and Tobago—was walking to surrender himself to the authorities to serve a ten-day jail sentence. His crime? He led the largely black and Latino union membership in a strike against New York City’s transportation authority the previous winter, in violation of New York’s draconian Taylor Law.21

For engaging in the sixty-hour strike that shut down the city’s subway and bus system, TWU Local 100 was fined $2.5 million in 2005. On top of Toussaint’s jail time, the courts suspended the union’s ability to collect dues money for a year, and each individual striker was fined two days pay for every day on strike. Such draconian punishments are rare outside the world of labor law. How did this ever pass constitutional muster?

A century and a half ago, our nation was rent by a bloody civil war, centered on the issue of treating labor like property. Well over half a million Americans lost their lives in battle over perhaps country’s greatest sin: slavery and the privilege of property rights over human rights.

When the smoke cleared, the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution seemingly settled the matter in stark and definitive terms: “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” (Emphasis added.) To this day, it remains the only section of the Constitution that expressly limits the power of individuals over each other. It is labor law explicitly codified in our nation’s governing document.

The Reconstruction Amendments, of which the Thirteenth was a part, were radical restatements of the concept of human freedom, but anti-labor jurists of the post-Reconstruction period reinterpreted them to fit within the common law framework of “at will” employment; freedom from involuntary servitude was, to them, merely the freedom to quit the job entirely.

Union activists following Reconstruction vociferously disagreed. “For decades,” writes James Gray Pope, “workers and unions had resisted injunctions, nullified antistrike laws, and sought legislation under the banner of the Thirteenth Amendment.”22 Leaders of the American Federation of Labor, he writes, tried in vain to have the constitutional authority of the NLRA rooted in Article XIII Section 2’s positive assertion of Congress’ “power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.”

As has been noted, these efforts failed. As a result, labor’s basic civil rights are judged based upon their impact on commercial activity. Labor must assert the existence of a constitutional right to strike that transcends the current state of labor legislation.

How to Restore This Right

Public sector antistrike legislation seems like a logical starting point for establishing that workers have a constitutional right to strike, because it is an example where the employer (government) also makes and enforces the law; thus, the employer has the ability to compel its workers to keep working, subjecting employees who defy its order to financial penalties and jail time. The framers of the Thirteenth Amendment would likely have viewed that as “involuntary servitude.”

Perhaps the best first cases are in instances where public sector employees are compelled to work without compensation. For example, case law has developed from New York’s Taylor Law that says that workers cannot engage in concerted actions to refuse to perform voluntary duties, such as chaperoning prom, if they had regularly volunteered prior to a contract dispute. And in Detroit, schoolteachers have been told that the district will run out of money to pay them for days they have already worked, but at the same time, they will be breaking the law if they do not continue to work for no pay.23 This command to work for free or go to jail is the very embodiment of involuntary servitude.

The right to strike must also include the right to return to the job when the strike is over. That was the clear intent of the National Labor Relations Act, which protected workers who engaged in concerted union activity from “discrimination in regard to hire or tenure of employment or any term or condition of employment,” and further declared, “Nothing in the Act should be interpreted to interfere with or impede or diminish in any way the right to strike.” And so, one important goal for restoring the right to strike must be reversing the flimsily considered 1938 Supreme Court precedent, NLRB vs. MacKay Radio,24 which granted employers the right to permanently replace striking workers.

For reasons that are not articulated in MacKay Radio, the Court ignored the plain language of the NLRA to declare that an employer has a:

[R]ight to protect and continue his business by supplying places left vacant by strikers. And he is not bound to discharge those hired to fill the places of strikers, upon the election of the latter to resume their employment in order to create places for them.

While the MacKay doctrine would appear to benefit from stare decises (the legal principle “to stand by things decided”), the fact remains that the Court has not, in any case that cited MacKay, gone back and evaluated the facts and logic of the original case. As Julius Getman notes, “the Court in MacKay made no effort to justify its dictum. And it’s actual holding points in the other direction—namely, that an employer may not base reinstatement rights on participation in union activity.”25

How is giving employment preference to workers who did not engage in strike activity not an act of discrimination against the employees who did participate in protected concerted activity? And why does it follow that retaining permanent replacement workers after the strike is over is necessary to “protect and continue his business” when there are more experienced, veteran employees ready, willing, and able to work?

Of historical note to any judicial reconsideration of MacKay is that employers did not exercise this right en masse until 1983. That year, the Phelps-Dodge Corporation laid out the union-busting blueprint by bargaining their employees to impasse over drastic cuts in pay, benefits, and working conditions, forcing them out on strike, and then helping the permanent replacements to decertify the union twelve months later.26

Many thousands of union bargaining units have been decertified using a weaponized form of the MacKay doctrine since the 1980s, and I am not aware of any significant judicial evaluation of whether any case of union-busting was necessary to “protect and continue” of the businesses who have exploited this law.

MacKay should be challenged as a violation of workers’ First Amendment rights of free speech and assembly, Thirteenth Amendment protections against involuntary servitude, and Fourteenth Amendment guarantees of due process and equal protection. It should be challenged on the basis of legislative intent, and it should be challenged based upon the justification of the original decision as compared to its practical application by employers since 1983.

Of equal importance is returning to the broad prohibition against federal injunctions of labor strikes, pickets, and boycotts in the 1932 Norris-LaGuardia Act. This requires challenging the 1970 Boys Market vs. Retail Clerks Supreme Court decision as a violation of workers’ Thirteenth Amendment rights.

In that case, the Court decided to ignore Norris-LaGuardia’s sweeping ban on federal injunctions in cases where a union strikes in violation of a signed no-strike clause. This decision, charges legal scholar James B. Atleson, “while ostensibly grounded on neutral concerns for the integrity of state court jurisdiction and authority, in fact was based primarily on the Court’s value choice that there is no effective substitute for an immediate halt to a strike.”27

Many scholars agreed with the Court that the concerns that motivated the Norris-LaGuardia Act were no longer present since courts were no longer anti-union and unions were now strong and established. Moreover, standards now existed to protect against judicial abuses because the cases would involve breaches of written agreements.28

And sure enough, once the Supreme Court legitimized injunctions to enforce contract terms, soon courts found more kinds of strike actions to enjoin. If a contract deliberately does not contain a no-strike clause, courts may assume and enforce a no-strike principle if that contract includes a grievance and arbitration process. And where a contract has expired—or not yet been negotiated—courts may enjoin partial and intermittent strikes. And in this way, the labor injunction that Felix Frankfurter railed against in the early part of the twentieth century has crept back into practice as employers have no shortage of case law to cite when appealing to a judge to order a union to cease its protest.

Partial strikes (where workers in a handful of essential job titles or categories strike while the rest of their co-workers continue to report for work) and rolling, or intermittent, strikes (where workers may strike for one day—or even one hour—and then report back to work the next day only to briefly strike again a short time later) can be incredibly disruptive, and therefore powerful, union tactics, so business-friendly judges made them “illegal.”

The tendency of judges to place a heavy thumb on the scale for business and property when weighing the relative merits of a labor-management dispute is precisely why Congress passed the Norris-LaGuardia Act: to bar them from getting involved in the first place. As they did before the passage of Norris-LaGuardia, unions should routinely appeal, challenge, and oppose any judicial injunction against a job action as a violation of those workers’ Thirteenth Amendment protections against involuntary servitude.

Labor’s Fourth Right: Labor Organizing Efforts Should Be Free from Unreasonable Search and Seizure

On a Fall day in 2008, the figurative autumn of the presidential administration of George W. Bush, officials at the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) inked an organizing rights deal for employees of the global security firm G4S. These sorts of agreements are an essential tool for workers to freely and fairly choose whether or not to be represented by a union. This is doubly true for security workers who are statutorily barred from seeking a union certification election with the National Labor Relations Board, if they are joining a union that also represents non-guards.

The agreement was the culmination of a years-long campaign run by a global coalition of unions. Faced with a pressure campaign that transcended national boundaries, G4S zeroed on where they had the most power to undermine its general thrust: the U.S. legal system. Specifically, the company filed a civil lawsuit against SEIU under the Racketeering Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO).29

More and more organizing and counter-organizing occurs outside the context of traditional labor organizations, and outside the context of the NLRB.30 To be successful, many unions engage in what are called “comprehensive campaigns,” which may utilize legal and regulatory challenges aimed at creating liabilities for employers and interfering in complex business deals to augment worker activism.

Through statutes such as the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) or Title VII, courts can offer workers a better chance to remedy workplace violations. Current labor law reform legislation in Congress, such as the Employee Empowerment Act and WAGE Act, seek to expand workers’ access to courts for labor violations. But however much there is an advantage to access to the courts, they can also present a host of new problems.

Two major areas where court proceedings have been used against workers include the RICO Act to go after unions engaging in comprehensive campaigns, and a host of abusive litigation tactics against workers seeking to vindicate their workplace rights in court, particularly “strategic lawsuits against public participation” (SLAPP) suits.31 Both sets of tactics have the intended purposes of chilling organizing activities by those with superior access to resources, and both should be pushed back against.

If workers are to have meaningful workplace rights, they cannot be subject to RICO and SLAPP suits for exercising those rights.

These cases are almost always without merit, but they can tie up a tremendous amount of a union’s money and staff attention in getting them dismissed. Indeed, the G4S RICO suit was hardly the only one darkening the skies over SEIU at the time. The global solidarity campaign did eventually put enough pressure on G4S to bring them to the table with SEIU. But the equal pressure of the RICO suit gave the company a bargaining chip to get the union to settle for a deal that protected fewer workers than the union had sought to organize (and fewer, comparably, than their foreign counterparts). As one corporate attorney told the New York Times about their use of RICO suits to get settlements from the union, “When they settle it normally breaks the campaign.”32

Although the deal involved a commitment by G4S to withdraw the RICO suit, that proved to be an unnecessary concern. A federal judge moved to dismiss the meritless case just hours after it was already withdrawn.

The use of RICO suits against labor is not merely an expensive distraction; it also is “an attempt to revive a nineteenth century conception of unions as extortionate criminal conspiracies.”33 Recognizing that organized crime had become “a highly sophisticated, diversified, and widespread activity that annually drain[ed] billions of dollars from America’s economy by unlawful conduct and the illegal use of force, fraud, and corruption,” Congress passed RICO with the purpose of “seek[ing] the eradication of organized crime in the United States.”34 However, starting in the 1980s, employers began using civil RICO to attack labor. The purpose of such suits is often to destroy effective comprehensive campaigns.35

Employer use of RICO suits when unions are trying to organize a workplace using a corporate campaign treats legitimate organizing tactics as coercive or extortionate,36 and assigns a property value to the free speech and assembly of a civil rights organization. These suits not only expose unions and union officials to major liability, but also link unions with criminal activities. Anti-union groups such as the National Right to Work Committee then promote these suits to further that linkage, and preserve the notion that unions are criminal organizations.

The malicious prosecution of labor is not limited to RICO suits; it is also used in SLAPP suits. The term “SLAPP suits” stems from an influential study that resulted in a book and series of papers that sought to identify a growing trend where citizens and groups were being sued for engaging in a variety of political or other conduct.37 These activities were as diverse as circulating petitions for signatures to reporting police misconduct, with the purpose of the suits being to silence opponents and dissuade certain conduct.38

Whereas early SLAPP suits were most common in zoning and other land use disputes, their use by employers has been growing.39 Hallett provides an example of such suits that is becoming all-too common where in response to a lawsuit by temporary guest workers that alleged involuntary servitude, wage theft, and other employment law violations, the employer filed counterclaims for “defamation/libel, invasion of privacy, tortious interference with business relations, intentional infliction of emotional distress, abuse of process, and civil conspiracy.”40 These tactics are, in many respects a modern-day continuation of employers using the courts as a weapon against workers.41

Workers have some limited protections in the form of the anti-SLAPP suits passed by a variety of states, but Hallett proposes the creation of a labor organizing privilege that would shield communications made between workers in the context of organizing. But these do not offer robust protection against attacks using the courts because not all states have such statutes.42

Courts recognize the need to protect privileged communications between attorneys and clients, priests and penitents, physicians and patients, between spouses, and others. By placing communications in the privileged camp, they become free from the fear of SLAPP suits and other forms of intrusion. In determining whether a communication should be privileged, and exempt from disclosure, the test developed by legal scholar John Wigmore is usually applied. This test requires that:

- The communications must originate in a confidence that they will not be disclosed.

- This element of confidentiality must be essential to the full and satisfactory maintenance of the relation between the parties.

- The relation must be one which in the opinion of the community ought to be sedulously fostered.

- The injury that would inure to the relation by the disclosure of the communication must be greater than the benefit thereby gained for the correct disposal of litigation.43

Based on this test, some jurisdictions have recognized a privilege protecting communications with a union representative.44 Hallett goes one step further in arguing that the Wigmore test and other societal factors show that a labor organizing privilege should be recognized. Such a privilege “would be held by the worker and would protect communications concerning organizing or collective bargaining between two or more workers, or between workers and their representatives.”45 The courts have granted broad managerial discretion to the physical workspace, but labor should push back against intrusions and after-the-fact surveillance on worker communications.

How to Restore This Right

Section 7 of the NLRA protects workers rights to engage in “concerted activities for the purpose of collective bargaining or other mutual aid or protection,” and Section 8(a)(1) categorizes employer surveillance as an unfair labor practice.46 Unions could file Unfair Labor Practices against employers that file meritless RICO civil suits, and an activist NLRB could deem the practice to be a violation of the labor act and possibly go to court to enjoin RICO suits from interfering with workers’ federally protected rights.

To have an arm of the government joining with a union to get a meritless RICO suit dismissed would be quite powerful. Having such an ally in the proceedings could open a space for unions to argue that the twisted misuse of RICO is a violation of their First Amendment rights of free speech and assembly and of workers’ Thirteenth Amendment right to be free from involuntary servitude.

Labor’s Fifth Right: The Freedom From Taking Away Union Fees (or, The Right to Dues Processing)

Imagine, if you will, a situation where the federal government required a private organization to work on behalf of all people who so requested, while a state law gave individuals the right to not pay for the service. It is likely that the only organization that one can imagine living under such rules is a labor organization.

This is because the NLRA has been interpreted to require a union, as the exclusive bargaining agent of workers in a bargaining unit, to represent all workers equally. However, when a state passes a so-called “right-to-work” law, as permitted by the 1947 Taft-Hartley amendments to the NLRA, workers can choose to pay nothing for this representation. Such representation includes organizing, contract negotiation, contract administration, legal representation, and other work. Therefore unions are in a situation where federal labor law requires them to provide a valuable and resource-heavy set of services to all workers, while state law permits workers to choose not to pay any fees. This would be akin to a law that requires Major League Baseball to admit all fans, but does not require them to buy a ticket. No other type of organization in America suffers under such a rule.

Yet, for decades, unions have reserved their arguments against right-to-work to the legislatures and the ballot box, not the courts. But, aided by legal scholars and jurists, unions have now begun making a constitutional argument against right-to-work, and though this argument has conservative roots, it should be pursued in state and federal courts. The argument essentially states that by having a federal law (the NLRA) that requires unions to represent every employee in the bargaining unit equally, while also allowing states to pass laws that require unions to do so for free, the government is unconstitutionally taking the unions’ services.

The argument first arose in labor’s challenge to Indiana’s controversial 2012 right-to-work law. Although the federal Seventh Circuit ruled against labor in Sweeney vs. Pence, Judge Diane Wood (who is among the most respected Circuit Court judges, and has been shortlisted for the Supreme Court)47 made a broad argument that right-to-work laws, by their very natures, violate the U.S. Constitution’s prohibition.48 Challenging the near six-decade acceptance of the validity of right-to-work laws, Judge Wood wrote that the majority “is either incorrect or it lays bare an unconstitutional confiscation perpetuated by our current system of labor law.”49

Judge Wood explained persuasively that Section 14(b) of the NLRA, which has been read to permit state right-to-work laws, should be read as it was written, speaking only to “agreements requiring membership.”50 Agency fees, which are currently interpreted as prohibited under right-to-work laws, are paid in lieu of membership. They are equivalent to only the portion of dues that compensate for collective bargaining, contract administration, and grievance adjustment.

Judge Wood argues, rather persuasively, that such agency fees were precisely what are permitted under Section 14(b), because the contrary reading would require the court “to decide whether such a rule is permissible under the Takings Clause of the Fifth Amendment,”51 Judge Wood’s interpretation challenges the long-accepted idea that states can pass laws that limit unions’ abilities to collect full membership dues from members and partial agency fees from non-members. It challenges these laws on what she calls “the two most basic economic rights enjoyed in the United States . . . (1) that the government may not confiscate private property for public use without just compensation, and (2) that the takings power must be exercised for a public purpose, and so the government may not take the property of one private party for the sole purpose of transferring it to another private party, regardless of whether ‘just’ compensation is paid.”52

How to Restore This Right

Labor has followed this cue and filed cases in state courts in Wisconsin and West Virginia, challenging those states’ right-to-work laws. In one brought by the International Union of Operating Engineers, with Harvard Law professor Ben Sachs serving as counsel, the union brought forward Judge Diane Wood’s argument that right-to-work laws were both preempted and an unconstitutional taking. IUOE Local 370 v. Wasden, 2016 WL 6211272 (D. ID, 2016). The District Court judge rejected the union’s argument, expressly siding with the Circuit majorities in Sweeney. This case is currently on appeal to the Circuit. Federal challenges have also been filed in the Fourth and Ninth Circuits, against West Virginia’s and Idaho’s laws.

Given that so many of these laws have only been passed in recent years, and as a part of a coordinated partisan attack on unions because they help Democrats get elected, these cases may find judges sympathetic to additional free speech and equal protection arguments incorporated into these judicial appeals.

Labor should engage in a full education and public relations campaign to complement the lawsuits and expose the unfairness behind this long-standing rule. Labor opponents have long employed constitutional arguments to push right-to-work in the courts and legislatures. In her dissent, Judge Wood laid out a roadmap for labor to challenge such laws on constitutional grounds.

Labor’s Sixth Right: The Right to Not Be Locked Out for Exercising Labor Rights

On the morning of Monday, May 9, 2016, Honeywell Aerospace employees in South Bend, Indiana, and Green Island, New York found themselves locked out of their factories.53 Their United Auto Workers (UAW) collective bargaining agreement with the company had expired six days earlier and the union members had voted by a nine to one margin to reject the company’s “last, best and final” offer. While that offer did include modest wage increases, it also called for health insurance premiums to rise by 67 percent with deductibles increasing by $4,600 a year. It also gave management more authority to force employees to work overtime.

The union offered to continue to work under the old contract while negotiations were ongoing. But the company decided to put severe economic pressure on their unionized workforce to accept its terms. Salaried employees and temps, who had been brought in during the previous weeks to shadow the company’s workers and learn their jobs, would be keeping the assembly line going. The locked out union members, of course, immediately lost their income while bills continued to pile up.

The workers at Honeywell remained locked out for ten long months. Midway through the conflict, the company’s spokesman has said Honeywell “will resume negotiations whenever the union is ready to do so,” while undermining that claim by reiterating that the company had already given the union its “last, best and final offer.” In essence, the company is punishing the workers for organizing and collectively bargaining.

Labor lockouts—both full and partial—are a particularly egregious form of workers’ losing the right to direct the terms of their own labor. The lockout occurs when an employer, very much like Honeywell, locks out its workforce as a bargaining tactic to gain concessions from the workers. Partial lockouts occur when an employer locks out only a portion of the workforce, and in many instances, the Board has permitted such tactics,54 while severely restricting unions’ right to engage in partial strikes. The lockout has been long treated as the complement to the strike, with a strike constituting workers withholding their labor and a lockout being management withholding work. Though there is an appealing logic to this view of lockouts, it ignores the realities of labor and goals of labor law.

Labor lockouts occur in the context of bargaining a contract between the union and the employer. Often negotiations are still underway, and the union has agreed to work under the terms of the expiring or expired contract. The employer, however, decides to lock out the entire union in order to gain greater concessions. Though the NLRA’s central protection states that “Employees shall have the right to self-organization, to form, join, or assist labor organizations, to bargain collectively through representatives of their own choosing, and to engage in other concerted activities for the purpose of collective bargaining or other mutual aid or protection,”55 in this instance, the NLRB and courts have looked the other way when employers punish workers for engaging in those protected activities.

If workers have a right to form a union in order to bargain collectively, how can it be permitted to withhold work and compensation for engaging in collective bargaining and making negotiation demands?

If workers have a right to form a union in order to bargain collectively, how can it be permitted to withhold work and compensation for engaging in collective bargaining and making negotiation demands? Furthermore, workers have a fundamental right to strike.56 Indeed, strikes or the threat of strikes is among workers’ few powerful tools in collective bargaining. However, in order for the right to strike to be meaningful, workers must be able to control the terms of their work stoppages. When an employer preemptively, or otherwise, locks workers out, it robs those workers of their full rights to strike.

It also robs them of a more literal “right to work.” In her book, The Workplace Constitution, University of Pennsylvania law and history professor Sophia Z. Lee documents attempts by early civil rights activists to get the due process guarantees of the Fifth Amendment and the equal protection rights of the Fourteenth to apply to apply to the workplace.57 These activists argued that there was a constitutional right to work in whites-only jobs for black workers, and they argued that NLRB regulation of collective bargaining provided the requisite state action to put the issue in the courts. Similar arguments should be revived against the lockout.

The act of locking out workers as a result of forming a union or engaging in collective action is incompatible with these core protections of the Act. The employer’s right to lockout workers has expanded over the last several decades from a series of conservative Labor Boards and courts, and it is time for labor to start pushing back against this affront to workers’ fundamental rights.58

How to Restore This Right

Labor should begin pushing back against the use of the lockout by challenging them on their face. If an employer locks out workers for engaging in concerted activities, including organizing a union and making demands in the collective bargaining process, unions should file unfair labor practice charges arguing that the lockout violates section 8(a)1 by interfering with their members’ concerted activity and section 8(a)3 by discriminatorily withholding pay from workers who are merely engaging in union activity, and when the case gets to the courts, argue that the lockout deprives workers of their due process rights under the Fifth Amendment.

Labor’s Seventh Right: The Right to Your Job

Last June, Samuel was called in to his company’s human resources office. As he recounted to Forbes magazine, he had been employed with his company for five years, and had just received his fifth annual performance review in March, a mix of his usual “Excellent” and “Very Good” ratings in every category.

His manager for the previous two and a half years was out on sabbatical. Samuel had barely had any interaction with his new manager. In the meeting, Samuel was blindsided by an announcement that he was being let go, as part of a general shake up of the firm.59

This is not a particularly dramatic story (except, of course, for Samuel and his family), but it is a very common one. Without a union, most workers in this country labor under a judicial standard called “at will” employment. Essentially, “at will” employees have the freedom to quit their job at any time, and employers have the even greater power to fire employees at any time, for a good reason, a bad reason or no reason at all. As with so many other areas of labor and employment, the symmetry is a false one.

Without a union, most workers in this country labor under a judicial standard called “at will” employment.

The alternative to at-will employment is “just cause,” which is the principle that an employee cannot be fired unless it is for a good, or just, reason. Generally, this means that the infraction for which an employee is being terminated is serious enough to warrant losing her job and that the employee has been given clear feedback on her shortcomings and time and support to improve her performance.

This is very commonly negotiated into union contracts.

As union density has shrunk, labor’s enemies are increasingly able to portray the job protections that union members have won for themselves as a special right that non-union workers should be jealous of. This is particularly true in the self-styled education reform movement, which has put teacher tenure in the crosshairs.

A union-led push to expand just cause protections for all workers could give unions more mass appeal, by providing a big, visible campaign of unions pushing for universal rights that employers have sought to restrict as “special” ones.

The strange thing about the at-will doctrine is that Congress never voted on it. It is not a statute, nor is it found in the constitution. It is entirely judge-made law. Early on in our nation’s history, judges imported the at-will doctrine from English common law. This came as the industrial revolution was breaking up the traditional relationship between master craftsmen and their journeymen and apprentices, and ensured that the new class of capitalists had no obligations to displaced workers.

Here too, unions once made arguments that the “nor involuntary servitude” clause of the Thirteenth Amendment altered the imbalance of power in the common law, but judges resisted that interpretation. The workers who fought in the Revolutionary and Civil Wars certainly didn’t think they were fighting for a definition of liberty that is you can be fired at any time.

In some respects, this is the one right that may be most cleanly legislated. There is nothing stopping any state in the nation from adopting a law that simply states, “No one who works in this state may be terminated from employment by their employer except for just cause” and instantly nullify the at-will employment standard for everyone in the jurisdiction.

Call it a “Right To Your Job” law. It may be achieved by a majority vote of the state legislature, a ballot initiative, or an amendment to the state constitution. But those areas of the country where activists are successfully winning the $15 minimum wage, paid sick days and fairness in scheduling laws should consider adding just cause to their list of initiatives. Once there has been enough public education and organizing on the issue, it may well prove to be one that, like the minimum wage, draws more progressive voters to the polls in off-cycle elections.

How to Restore This Right

If that happens, judicial activism on this issue will arise in implementation. While some states might choose to legislate that termination disputes be submitted to a labor or employment board of some kind, others may leave it to lawsuits or private arbitration. Preserving the right to sue, as a matter of leverage, while pushing for a body of arbitration “case law” that parallels the voluminous labor-management case law in which many lawyers and union representatives are well-versed could keep many lawyers plenty busy.

Making the demand for just cause for all public and popular could open the door to litigation strategies to establish the right. The fact is that pure at-will status no longer exists. Civil rights statutes, whistleblower protection laws and the labor act itself already limit the ability of employers to terminate protected workers for bad or no cause. Googling a phrases like “I was fired for no reason” bring a host of links providing advice and law firms advocating for how to fight back. Most of that advice runs along the lines of trying to shoehorn an unexplained termination into one of the existing protections.

If the concept of just cause for all gets into the popular imagination, it’s not impossible to imagine employment lawyers incorporating constitutional arguments into their wrongful termination lawsuits that that just cause protections should be equally applied to all workers, and to some judges becoming sympathetic to their arguments.

The argument would be that laboring under the implied threat of termination at any time violates an employee’s Thirteenth amendment right to be free from involuntary servitude, and that by only extending job protections to certain “protected” classes of workers, the workers who do not currently enjoy just cause protections are being denied their Fourteenth amendment right to equal protection under the law.

Labor’s Eighth Right: Freedom from Cruel and Unusual Regulation

On May 15, 2014, workers at a Staples warehouse in Georgia who were trying to organize a meeting were called in for a mandatory captive audience meeting led by one of the managers.60 In the meeting, the manager explains how Staples cares about its associates, and wants to work directly with them. He explained that “unions come between employers and employees.” And warned “Unions are a business that needs your money. Don’t be fooled: Unions are first and foremost a business.”61

To anyone who has listened to secret recordings of captive audience meetings, or viewed confidential speeches for employers to lead an anti-union campaign, the manager’s words seem strangely familiar.62 But to many workers who are forced to listen to these speeches, they don’t know that behind the speeches and literature is a vast “union avoidance” business that their employer has engaged to keep workers from exercising their rights to form a union. For over fifty-five years, the law has required employers to disclose when and who they hire to persuade employees concerning their labor rights, but for almost as long, employers have utilized an interpretive loophole that allows union-busters to remain in the shadows.

While the “union avoidance” industry is allowed to operate in the shadows, the exact opposite is true concerning union activity. If one wants to find out how much any union staffer makes, or how much she was reimbursed for mileage, one need only go to the website www.unionfacts.com. The site is not an investigative news source that cleverly finds inside information on unions. Rather, it is run by an anti-union group called the Center for Union Facts (established by Richard Berman, also known as “Dr. Evil”), and has been able to create their easily searchable database and whip up outrage against unions because labor organizations are required to make massive disclosures.

Whether for good or bad, labor unions are among the most regulated organizations in America. The Taft-Hartley of 1947 began limiting union structures and requiring anti-communist affidavits from union officials. Then, in 1959, the Labor Management Reporting and Disclosure Act (LMRDA) placed strict rules on who can serve as a union official, as well as strict reporting requirements. Unions have to submit to the Department of Labor each year data on income and expenditures, salaries, and a host of other internal documents. Furthermore, following court decisions concerning agency fees, unions must disclose strict accountings of how every dollar is spent in order to determine if it is a “chargeable” or “non-chargeable” expense.

On the employer side, the LMRDA required employers to file reports with the DOL when they hire anti-union consultants (often called “union busters). The theory behind this requirement is that workers have a right to know who is speaking to them when they are receiving information from their employers, and they have a right to know how much the employer is paying for its campaign against the union. However, a huge “advice” exemption has developed wherein a consultant who does not make actual contact with the workers, but only provides all the resources behind the scenes to run an anti-union campaign, is exempt from the law. It is estimated that employers in 71–87 percent of organizing drives hire one or more consultants, yet because of the massive loophole in the law, nationwide only 387 agreements were filed by employers and consultants.

A Department of Labor rule was scheduled to close this loophole, until a federal district court judge in Texas placed a nationwide injunction preventing the rule from going into effect.63 The ninety-page decision focused exclusively on the employer’s First Amendment right not to disclose their use of consultants. Though the title of the LMRDA sounds like it affects both labor and management, management has effectively been exempt from its reach.

How to Restore This Right

Labor law is constructed on the principle of a balance of power between the employer and employees. But, as in so many other areas, labor has it much harder in terms of the disclosures it is required to make. Disclosure requirements are often ineffective measures, but if they are to exist, there must be parity. Just as workers have a right to know the salaries of every person at the union, they should have a right to know the salaries of every executive and other employee at the company. And just as workers have a right to know detailed union expenditures so that they can know if money that might otherwise adhere to their benefit is being responsibly spent, they have a right to know corporate expenditures.

Though the Department of Labor’s recent persuader rule is currently in legal limbo, labor should continue to push for greater parity of disclosure between labor and management—a sort of equal protection, whose benefit would adhere to workers. Such disclosures would allow workers to highlight and target employer expenditures that are wasteful or against the long-term interests of the enterprise.

Labor’s Ninth Right: The Right to Make Demands and Bargain Freely

In 2012, the Chicago Teachers Union (CTU) won a major strike. They were motivated by a desire to prevent school closures, strengthen layoff and recall rights in the event of closures, get air conditioning in every classroom and repair crumbling buildings and to get student test scores removed from teacher evaluations. They struck, however, out of legal necessity, for more money. That’s because wages are a so-called “mandatory” subject of bargaining, and the other items were deemed by lawmakers to be “permissive.”

In fact, after the strike’s first week attorneys for Mayor Rahm Emanuel went to court seeking an injunction to force the teachers back to work because picketers had been talking more about air conditioning than about raises. Of course, the CTU operates under a public sector labor law, wherein employers are the law and craft the law to naturally more favorable to them.

Ironically, if Republicans revive the Friedrichs vs. CTA case, it would establish that every interaction a union has with its government employer is political speech, paving the way for unions to challenge restrictions like Illinois’ on unions’ bargaining demands as violations of the First amendment.

Still, public sector scope of bargaining is based upon a similar framework in the private sector, one that similarly distorts collective bargaining and restricts the free speech of union members.

The National Labor Relations Act’s directive to employers to bargain with certified union representatives “in good faith” over “wages, hours and other terms and conditions of employment” is as broad as it is vague. There is no statutory requirement to actually reach an agreement—only to meet and respond to proposals.

Legal assistance, in the form of Unfair Labor Practice charges, only comes into play when one party refuses to meet or refuses to respond to a bargaining proposal. “Bad faith” bargaining ULP’s can bring significant leverage as remedies include orders to meet more frequently, the furnishing of budgetary and other documentation to justify a bargaining position and orders to cease, or even reverse, any changes made prior to reaching agreement or impasse.

Unfortunately, the obligation to bargain in good faith has been drastically narrowed by the Supreme Court’s artificial invention of “mandatory” and “permissive” subjects of bargaining. “Permissive” subjects carry no legal obligation to bargain, and the Court has privileged “managerial decision, which lie at the core of entrepreneurial control”64 in this manner.

As a result, an employer has no duty to bargain over a decision to subcontract, outsource or downsize employment of union members. At best, unions can compel an employer to bargain over the impact of a decision already made. As a result, unions have little legal right to bargain to save jobs and only a little more to bargain for severance payments.

In their ambitious and groundbreaking survey of worker representation preferences, What Workers Want, Richard B. Freeman and Joel Rodgers concluded that workers want “more” from workplace representation:

[M]ore say in the workplace decisions that affect their lives, more employee involvement in their firms, more legal protection at the workplace, and more union representation.

But “most workers do not believe that, under current U.S. policies, they can get the additional input into workplace decisions that they want.”65

My interpretation of these findings is that workers want co-determination.

Teachers at charter schools vote to form unions to gain a say in textbook purchases, advanced placement offerings, student discipline and extracurricular activities. Nurses organize to gain a voice in staffing ratios, patient treatment regimens, how patients are billed and when they are discharged. Autoworkers bemoan the fact that their employers design and produce cars that leave them, as auto consumers, unenthusiastic.

Above all, workers want the ability to veto or amend management’s decisions to downsize, subcontract, automate or shift work overseas. One of the most powerful taunts that employers make in union-busting campaigns is, “The union can’t save your job.” It is perverse that the law restricts unions from being what workers want them to be, and that pro-business commentators then sneer at the low levels of new union win rates.

How to Restore This Right

The place to begin expanding the scope of bargaining is the public sector, where a combination of statute and judicial interference has created a third category of undemocratic bargaining subjects: those restricted from even being proposed. In New Jersey, teachers unions are prohibited from proposing contract language to reduce class sizes (which is only one of the most important issue to teachers!), and all unions are prohibited from patterning proposals on what other unions in the state have won. Wisconsin infamously reduced the scope of bargaining so severely that unions are legally prohibited from proposing anything other than a wage increase that does not exceed the rate of inflation.

A government employer using the force of law to restrict its employees’ rights of free speech to advocate for the working conditions they desire, and to use the force of law to dictate working conditions to its employees—particularly in Wisconsin where hard-fought work rules and compensation were instantly revoked—is vulnerable to constitutional challenges based upon the First, Thirteenth, and Fourteenth amendments.

For the private sector, ultimately the NLRB vs. Wooster Division of Borg-Warner precedent must be overturned. In this case, the Court ruled that the employer could not refuse to bargain over pay and benefits (now deemed “mandatory” subjects) until the union agreed to stage a ratification vote in the manner the employer demanded (a “permissive” subject, if ever there was one). While the initial thrust of Court opinion had a laudable goal, the NLRB and the Court could simply have declared the employer’s demands regarding union governance to be a violation of section 8(a)2’s prohibition on employer dominance of unions, and the refusal to deal with pay and benefits, in and of itself, to be “bad faith” bargaining.

Once judges begin tinkering with what kinds of demands are fair and which ones are foul, then the very process of collective bargaining becomes warped, in the words of legal scholar James B. Atleson, by “the assumption that certain rights are necessarily vested exclusively in management or are based upon an economic value judgment about the necessary locus of certain power.”66 These obvious class biases of favor management and hamper industrial democracy.

While there is some truth to Atleson’s observation that “a party needing Board assistance to compel bargaining over a particular matter is hardly in a position to achieve notable bargaining success,”67 written as it was in 1983, it misses two key points. First, the value of ULP’s as a point of leverage in comprehensive organizing campaigns is a more recent tool for unions, one of particular value in contract fights where the employer’s ultimate goal is to break the union. Second, the first union members who do seek to have a voice in matters at the “core of entrepreneurial control” (marketing, quality control, environmental impact, etc.) will see employers strongly resist, to the point of necessitating legal assistance to break the logjam.

Labor’s Tenth Right: Powers Not Exercised by Unions Are Reserved to Workers Who Act in Concert

Like many nonunion white-collar workers, Jacob Lewis was getting screwed. A technical writer for a healthcare software company called Epic Systems,68 Lewis was a salaried employee who worked long hours with no overtime compensation. He did some research and talked with his fellow technical writers, who decided that they were being improperly misclassified as exempt from overtime laws.

A little while earlier, on April 2, 2014, Epic Systems, sent an email to its workers that included an arbitration agreement that required workers to bring their employment claims through arbitration while waiving their rights to bring a class action case. Such arbitration agreements have become widespread following a pair of Supreme Court decisions in 2011 and 2013 that effectively held that they were permissible in most instances.

Lewis, however, brought his overtime claim as a class action in court, rather than proceeding individually in arbitration. The company sought to have Lewis’s case dismissed because the agreement required him to proceed solely through arbitration. The Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals, in a decision written by Judge Diane Wood, however held that the National Labor Relations Act prohibited such class action waivers because such legal actions are among the Section 7 rights protected by labor law. In doing so, the Seventh Circuit doubled down on the NLRB’s important precedent in D.R. Horton that first held that collective and class court actions are substantive rights protected by labor law.69

Labor law in America is unique among the nation’s laws because it protects collective rights rather than individual rights. The individual worker is protected only insofar as she is part of a group that acts for mutual aid or protection. Though the collective rights model has at times proven problematic in application, or has been significantly misunderstood by judges, it also contains significant unique advantages.

Class action waivers have wreaked havoc on consumer and employer rights, and until recent decisions that viewed them in light of rights protected by the NLRA, it looked as if there was no stopping them.70 Class actions, which protect the rights of groups have long been considered to be merely procedural rights, even though they are often the only means for many to receive meaningful relief. However, through the lens of collective labor law, the Seventh Circuit found that the right to a class action is a substantive right that cannot be abridged in the workplace. If it stands, this decision now protects workers who want to bring all manner of workplace actions, whether or not there are class action waivers in place.

If the NLRA can be used to strike down class action waivers in the employment context, workers should try to extend the law’s protections to the myriad other areas where they are pushed into isolation in the workplace.

Already, there have been some very good free speech cases arising from workers’ use of Facebook to complain about employment practices that affect them and their coworkers.71 Crucially, a worker’s social media advocacy must apply to an issue that affects more than just herself in order to be protected concerted activity. More crucially, a worker must know that she has recourse to the NLRB even if she is not organized into a union.

The NLRB attempted to enforce a rule that would have mandated all covered workplaces to post a sign about employees’ rights under the labor act, alongside minimum wage and other relevant laws. That action was enjoined by conservative circuit court decisions, and the NLRB declined to appeal to the Supreme Court in January of 2014. The next Democratic NLRB should revive the effort.

How to Restore This Right

Potentially, a more effective education campaign is within the labor movement’s power. There is no small amount of Netroots-style digital organizers and social justice organizations who are skilled and creative in the use of social media. A few relatively small financial grants could fund a significant campaign of memes and popular education aimed at teaching young workers that there is power—and protection—in working in concert with your fellow workers.

The campaign of judicial activism that I advocate will require an exponential increase in the number of unfair labor practices filed at the NLRB. Unorganized workers at non-union firms experience hair-raising abuse on a daily basis. Availing themselves of the workers’ law will open up interesting opportunities to expand all workers’ rights.

Conclusion

In 1984, labor law scholar James Gray Pope began calling attention to what he termed a “black hole” in First Amendment jurisprudence.72 The courts had long provided various types of speech different levels of protection, wherein political speech received the greatest protection, commercial speech received a medium level of protection, and obscene speech or “fighting words” received no protection. However, in this “hierarchy of first amendment values”73 (as the Supreme Court termed it), there existed a “black hole,” wherein speech that would normally receive intermediate protection because it is commercial or maximum protection because it is political “may be sucked into the black hole when spoken by labor unions or workers.”74

The courts’ interpretation of the Constitution has changed a great deal since 1984, when Pope first described the ladder straddling a black hole. The Commerce Clause of the Constitution, which serves as the grounding for the nation’s labor law, has been diminished, and the First Amendment has been unevenly expanded for largely anti-regulatory purposes. However, the black hole still exists for labor.

Labor organizations and workers have generally not been treated kindly by the courts. However, there are certain fundamental rights that adhere to workers and the organizations that they choose to represent them that should be challenged at the courts.

There remains some value connecting labor rights to the Commerce clause.

The “Findings and Policies” section of the 1935 National Labor Relations Act was written with this telling paragraph [Emphasis added]:

The inequality of bargaining power between employees who do not possess full freedom of association or actual liberty of contract and employers who are organized in the corporate or other forms of ownership association substantially burdens and affects the flow of commerce, and tends to aggravate recurrent business depressions, by depressing wage rates and the purchasing power of wage earners in industry and by preventing the stabilization of competitive wage rates and working conditions within and between industries.

Today, there is a growing recognition that the massive and nearly unprecedented inequality in our country and the economic recessions that occur more frequently and hit with greater severity is a direct result of the decline of union membership. As a result, there are more courts willing to restore and defend workers’ rights. This trend will obviously be blunted by at least four years of right-wing judicial appointments, but it is the long-haul trend that must be aimed for.

Today, there is a growing recognition that the massive and nearly unprecedented inequality in our country and the economic recessions that occur more frequently and hit with greater severity is a direct result of the decline of union membership.

Likewise, there is a lesson in the activist policymaking of the NLRB, under the direction of General Counsel Richard F. Griffin Jr. In recent years, the National Labor Relations Board has taken some actions to help better balance the unequal bargaining position of unions. For example, it has expanded the joint employer obligations of franchises, expanded organizing rights for graduate employees and temporary workers, curbed employers’ unmitigated right to permanently replace strikers and expanded “make whole” remedies for illegally fired activists.