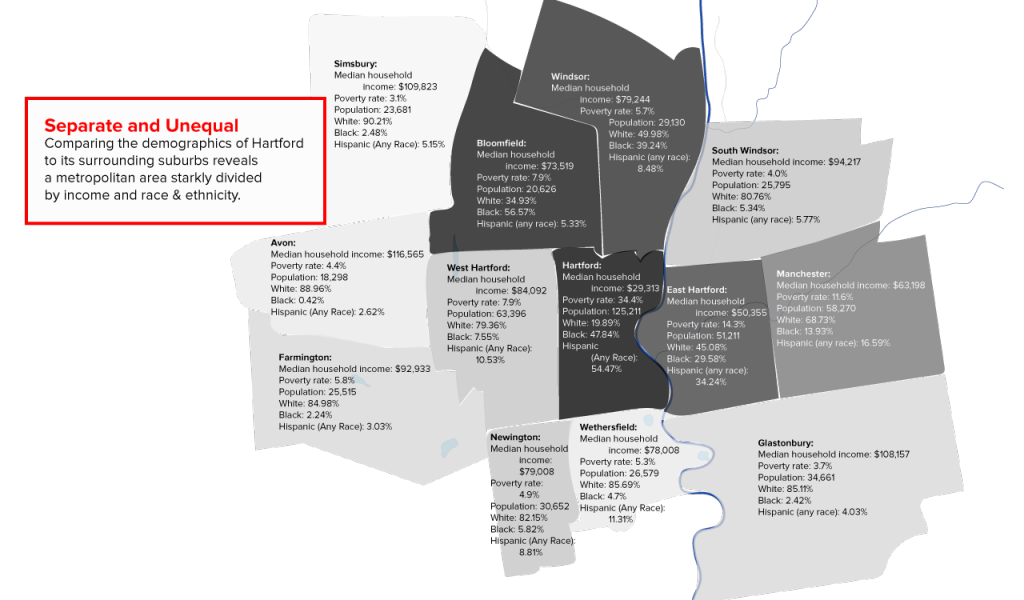

Hartford, CT, a high-poverty, majority-minority city of over 125,000 residents, is surrounded by several affluent, predominantly white suburbs. While the poverty rate in the city is 34.4 percent, the combined poverty rate of the surrounding counties is only 12.1 percent. Hartford is the fourth poorest city with over 100,000 residents in the country; in contrast, greater Hartford has the nation’s seventh highest median income. Hartford’s median household income ($29,313), percentage of owner occupied homes (23.6 percent), and median home value ($163,600) are each significantly lower than in the surrounding areas; respectively, these county statistics are $65,499, 65.1 percent, and $238,600. The unemployment rate in the city is nearly double the rate in the surrounding counties, at a startling 12.2 percent. Demographically, the city is approximately 15.9 percent white, 38.3 percent black, 43.6 percent Hispanic, with a median age of 30. In contrast, the surrounding areas are much whiter and older, with a white population of nearly 65 percent and a median age of 40.1 About 15 percent of Hartford’s residents have a bachelor’s degree or higher.

Hartford School District serves students from pre-kindergarten through the twelfth grade in sixty-eight schools. In the 2013–2014 academic year, it enrolled 21,820 students, with a per pupil expenditure of $16,735.2 Like the city itself, the school district is majority black and Hispanic—31.3 percent of its students are black; 49.9 percent, Hispanic. Nearly 85 percent of children attending district schools are eligible for free or reduced-price meals, and 16.9 percent of them are English language learners.3 These statistics include the demographic information of the suburban students who attend public school in the city, meaning that both the poverty rate and rate of racial isolation in Hartford Public Schools would be significantly greater save for its efforts in desegregation.

To help remedy the inequities between the city and surrounding counties, Hartford Public Schools operates an interdistrict magnet program that seeks to provide a wider range of educational opportunities to both Hartford and suburban families. Alongside this interdistrict magnet program that attracts suburban students into the city, Hartford’s open choice policy allows city children to attend schools in more than thirty surrounding school districts. This two-way desegregation plan has made Hartford a model for effective school integration in a high-poverty, high-minority district.

History of Integration Efforts in Hartford

Hartford’s contemporary push for school integration began with the 1996 Connecticut Supreme Court ruling in Sheff v. O’Neill. The lead petitioner, a Hartford fourth grader, filed a lawsuit through his parents, calling attention to the vast inequities between Hartford’s underresourced, majority-minority schools, and suburban schools that had predominantly white student populations. Seeking to ensure an equitable and integrated education to both urban and suburban children, the Connecticut Supreme Court ruled 4–3 for Sheff, determining that separation of suburban and Hartford students violated the education and equal protection clauses of the state constitution. The state was now obligated to remedy that division by finding ways to promote school desegregation.4 Significantly, while the U.S. Constitution’s prohibits only de jure segregation, the Sheff court ruled that the Connecticut constitution also prohibits de facto segregation—segregation not directly tied to intentional government conduct.

Despite the significance of the ruling, the case did not set specific goals or timetables, and the Sheff plaintiffs felt were forced to return to court twice to demand compliance. Both parties reached a legal settlement in 2003, setting a four year timetable and calling initially for at least 30 percent of Hartford minority students to be able to learn in reduced-isolation settings, or schools where minorities constituted less than three-quarters of the student body. This settlement also outlined ways to potentially reduce racial and economic isolation: interdistrict magnet schools, which enroll students from Hartford and suburban districts; and the open choice program, which allows students to transfer to a school in another district. The settlement also helped establish interdistrict cooperative programs such as after-school or summer programs designed to increase achievement while further reducing isolation. The parties negotiated a second settlement in 2008. The settlement set two new benchmarks. First, at least 80 percent of Hartford minority students wishing to attend reduced isolation schools would be accommodated. Secondly, a percentage of minority students from Hartford would be enrolled in a reduced isolation school; the target goals of the court order placed that number at 41 percent.5

In response to the 1996 Sheff decision, the state legislature devised a voluntary system of magnet schools and school choice transfer options that would be available options for both Hartford and suburban residents. Today, more than 45 percent of Hartford’s Black and Latino K–12 students attend schools in reduced-isolation settings. As recently as 2002, only an estimated 10 percent of black and Latino students could make this claim.6

Stories of School Integration

View the profiles of school districts and charter schools pursuing socio-economic integration.The Future of Brown Is Multiracial

How My Family’s Immigration Story Connects to Integration

New York City Public Schools: Small Steps in the Biggest District

Chicago Public Schools: Ensuring Diversity in Selective Enrollment and Magnet Schools

Hartford Public Schools: Striving for Equity through Interdistrict Programs

Stamford Public Schools: From Desegregated Schools to Integrated Classrooms

Dallas Independent School District: Integration as Innovation

Jefferson County Public Schools: From Legal Enforcement to Ongoing Commitment

Eden Prairie Public Schools: Adapting to Demographic Change in the Suburbs

Champaign Schools: Fighting the Opportunity Gap

Current Plan

Students in the Greater Hartford area can choose to participate in a variety of integration programs, including but not limited to open choice, or reverse choice, in which suburban public school children can apply to attend non-magnets in Hartford. The region’s most substantial option, interdistrict magnet schools—about forty-five in total—offer a specialized theme, focus, or pedagogy within the public school system.7 These schools are operated by a variety of partners. About half are operated by Hartford Public Schools, and most of the others are operated by the Capitol Region Education Council (CREC), a separate organization that serves thirty-five member districts in the Greater Hartford area. Magnet schools are funded through a combination of state grants, contributions from local boards of education, federal grants, and tuition paid by sending districts and towns. The Regional School Choice Office (RSCO), oversees the system and ensures that both Hartford and suburban families have access to integrated schools through a lottery system for magnet school admissions.8 Although RSCO seeks to accommodate as many children and families as possible through the magnet program, it cannot guarantee a seat to every pre-K–12 family that wants one. The lottery system is designed to meet a lofty goal: to have at least 47.5 percent of students enrolled in reduced racial isolation schools (defined as less than 75 percent minority enrollment).9

While race or income are not weighted factors in Hartford’s “blind,” computer-based lottery, the extreme racial and economic stratification of the Greater Hartford area renders the suburban-urban divide a reasonable proxy for creating socioeconomic and racial diversity. Most Sheff magnet schools are 50-50 city-suburban enrollment by design, which helps ensure both racial and economic integration. By recruiting children from the much more affluent areas, the Hartford School Choice Office is typically able to successfully enroll a threshold of non-minority students to the district-run interdistrict magnet schools to remain in compliance with Sheff directives. Conversely, those interdistrict magnet schools located in outlying suburban areas intentionally recruit students from both Hartford and suburban districts. This process of recruitment, however, is targeted, evidence-based, and well-funded. In 2015, the Hartford School Choice Office spent $350,000 in marketing campaigns alone, not to mention significant time and personnel resources.10 Interdistrict magnet schools or participating school districts receive state grants if they choose to provide transportation to out-of-district students, and the district where the school is located is obligated to provide transportation to its resident students. According to reporting by the Connecticut Mirror, the state has spent around $1.4 billion to build and renovate magnet schools over the past ten years, and spends about $150 million to operate these schools each year.11

Impact on Integration and Student Outcomes

Hartford Public Schools, a school district with an extremely disadvantaged student population, provides a greater range of educational opportunities to its students than any other district in their region. Its regional magnet schools offer far more racially and economically integrated student bodies than nearly every other non-magnet school in the region, save one. Several researchers and at least one of the magnet school operators report strong academic outcomes for students enrolled in interdistrict programs.

Expansion of Access to Desegregated Schools

Since most school segregation today happens across—rather than within—school districts, Hartford’s use of interdistrict desegregation programs helps to maximize the proportion of students with access to diverse school buildings. Because of this, the percentages of Hartford students who attend reduced racial isolation schools has increased from only 11 percent prior to the revised Sheff agreement in 2007, to a projected 45.5 percent in 2016.12 In 2014, 9,558 of Hartford’s 21,458 minority students were able to attend schools in these more integrated settings. More than 17,000 students in the Hartford region attend magnet schools; another 2,000 participate in the open choice program. CREC (an organization that works with member districts to run many of the Hartford region’s magnet programs) has itself expanded from 3,600 students in 2008, to 6,300 students in 2012. The overall enrollment in their schools is close to one-third white, one-third black, and one-third Latino.

Elevated Achievement and Better Social-Emotional Outcomes

According to researchers at UCLA’s Civil Rights Project, Hartford’s regional magnet schools boast very high levels of achievement and a greatly diminished white-Latino student achievement gap in several subjects and grade levels. Within each racial group, the students from poor backgrounds perform substantially above the statewide average for low-income students, and the longer an individual student has remained in magnet schools, the more substantial his or her gains seem to be.13 For example, while stubborn racial and socioeconomic achievement gaps persist within CREC schools, the achievement of student racial and socioeconomic subgroups far exceed state averages, and the score gaps between those students and their white or more affluent peers are notably more narrow.14 CREC schools saw these encouraging outcomes even though their schools have a higher percentage of poor students than the state average.

This more recent data bears out the findings in a pair of peer-reviewed 2009 studies from Connecticut that sought to discover both the true integrative effect of magnet schools and their impacts on student achievement. Controlling for the possibility for selection bias, or the concept that children from families who opt-in to schools of choice are fundamentally different from children from families who do not, researchers looked at magnet school lottery winners and losers and discovered that attendance at a magnet high school had positive math and reading achievement outcomes for central city students.15

A second study by the same researchers, again controlling for both selection bias and past educational experiences, revealed a number of positive social-emotional developments for all students in Hartford’s interdistrict magnets. Students in these desegregated environments reported greater levels of peer support for academic achievement, more encouragement and support for college attainment, and lower rates of truancy and absenteeism. Both white and minority students were more likely to feel connected to peers of other races, to report having multiple friends of different racial and ethnic backgrounds, and to express stronger interests in and understanding of multiculturalism.16

Next Steps

The popularity of Hartford’s interdistrict magnet program also presents one of its greatest challenges: figuring out how to simultaneously attract enough affluent suburban families into the program to sustain its integrative effects while maximizing magnet school access to marginalized urban children who are most in need of it.

Inclusion of More Hartford Families

Demand for admission into the Hartford region’s interdistrict magnet schools far outpaces supply. Bruce Douglas, former executive director of CREC, told the Huffington Post that in this academic year, there were 20,000 applicants for 2,000 seats in CREC schools.17 This pattern seems to expand throughout the Hartford interdistrict magnet network. Simultaneously, as more black and Latino families begin to move out of city proper into surrounding districts, Hartford officials seeking to find more affluent white families to balance Hartford schools are forced to venture further and further into the county to recruit. All of this leads to a program that—while its intentions and ultimate effects are to help bolster achievement and opportunity for marginalized kids—does so by actively seeking the approval, enthusiasm, and attendance of richer, whiter families.

This situation is not aided by what seems to be wavering political enthusiasm for magnet school funding in a state with budget challenges. While the Connecticut state legislature protected funding for Hartford’s magnet schools due to intense demand, it placed a moratorium on all other future magnet school construction in 2009. Recently, however, a bill signed by the governor in July 2016 allocates tens of millions of dollars to magnet school construction projects in the Hartford region.18 These additional funds will likely help open up seats for more low-income Hartford city students in new schools with improved, state-of-the-art facilities and creative themes or pedagogies. But in order to persist as reduced isolation schools, Hartford and regional school officials must continue rigorous marketing research and recruitment in the suburbs, while further incentivizing suburban districts to accept greater numbers of Hartford city students through the region’s Open Choice program.

This profile is part of The Century Foundation’s Stories of School Integration series.

Notes

- Hartford, Connecticut, CERC town profile 2016, CT Data Collaborative, https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/cerc-pdfs/hartford.pdf

- “Hartford School District,” District Profile and Performance Report for School Year 2013-2014, http://edsight.ct.gov/Output/District/HighSchool/0640011_201314.pdf.

- Ibid.

- Brigit Rioual, “Sheff v. O’Neill Settlements Target Educational Segregation in Hartford,” Connecticut History, http://connecticuthistory.org/sheff-v-oneill-settlements-target-educational-segregation-in-hartford/.

- Ibid; Gary Orfield and Jongyeon Ee, Connecticut School Integration: Moving Forward As The Northeast Retreat, report, The Civil Rights Project, UCLA, April 2015, https://civilrightsproject.ucla.edu/research/k-12-education/integration-and-diversity/connecticut-school-integration-moving-forward-as-the-northeast-retreats/orfield-ee-connecticut-school-integration-2015.pdf.

- Tim Kennedy, “Hartford: Integrating Schools In A Segregated Place,” One Day Magazine, June 14, 2016, https://www.teachforamerica.org/one-day-magazine/hartford-integrating-schools-segregated-place.

- “School Integration in CT,” Sheff Movement, 2014, http://www.sheffmovement.org/school-integration-in-ct/.

- “Interdistrict Magnet Schools,” Connecticut State Department of Education, April 29, 2016, http://www.sde.ct.gov/sde/cwp/view.asp?a=2681&q=335098.

- Gary Orfield and Jongyeon Ee, Connecticut School Integration: Moving Forward As The Northeast Retreat, report, The Civil Rights Project, UCLA, April 2015, https://civilrightsproject.ucla.edu/research/k-12-education/integration-and-diversity/connecticut-school-integration-moving-forward-as-the-northeast-retreats/orfield-ee-connecticut-school-integration-2015.pdf.

- “How This Small Office is Working To Desegregate Hartford Public Schools,” ThinkProgress, October 26, 2015, http://thinkprogress.org/how-this-small-office-is-working-to-desegregate-hartford-public-schools-7f87ff14ee2#.excraghcx.

- Jacqueline Rabe Thomas, “A Stalemate in Desegregating Hartford Schools,” Connecticut Mirror, June 10, 2016, http://ctmirror.org/2016/06/10/a-stalemate-in-desegregating-hartford-schools/.

- Gary Orfield and Jongyeon Ee, Connecticut School Integration: Moving Forward As The Northeast Retreat, report, The Civil Rights Project, UCLA, April 2015, https://civilrightsproject.ucla.edu/research/k-12-education/integration-and-diversity/connecticut-school-integration-moving-forward-as-the-northeast-retreats/orfield-ee-connecticut-school-integration-2015.pdf.

- Ibid.

- Sarah S. Ellsworth, “CREC Student Achievement Overview 2013,” Capital Region Education Council Office of Data Analysis, Research and Technology, 2013.

- Casey D. Cobb, Robert Bifulco, and Courtney Bell, “Evaluation of Connecticut’s Interdistrict Magnet Schools,” Center for Education Policy Analysis, University of Connecticut, January 2009, https://assets.documentcloud.org/documents/1390103/cepa-evaluation-of-connecticuts-inter-district.pdf.

- Genevieve Siegel-Hawley and Erica Frankenberg, “Magnet School Student Outcomes: What The Research Says, issue brief, National Coalition on School Diversity (October 2011).

- Rebecca Klein, “Connecticut Makes Rare Progress On School Segregation As America Moves Backwards,” The Huffington Post, May 15, 2015, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2015/05/15/connecticut-school-desegregation_n_7269750.html.

- Jacqueline Rabe Thomas, “A Stalemate in Desegregating Hartford Schools,” Connecticut Mirror, June 10, 2016, http://ctmirror.org/2016/06/10/a-stalemate-in-desegregating-hartford-schools/.