It is surprising that one of the most successful and powerful social movements in the nation’s history—the labor movement—has not launched a coherent, large-scale digital organizing strategy to recruit a new generation of workers.1 This is true even though the nation’s commercial and political campaigns have used digital marketing for years with remarkable success. And this is true even though the labor movement has a significant brag—union members earn significantly higher wages, have more job stability, and better access to critical health and leave benefits.

While some direct-organizing efforts, such as Fight for $15, have had success in using digital issue campaigns to achieve better wages,2 hard-fought initiatives seeking to unionize the workplace more broadly in the private sector, such as OUR Walmart, did not succeed in adding a significant number of new union members.3

This inability to increase the ranks of unionized workers is part of a long-term trend. For decades, the labor movement has been in decline, stymied by labor laws too weak to restrain employer abuses and undermined by the fracturing of the workplace by employers who seek to shed any obligations to their workers (think Uber drivers). As a result, only 6 percent of private sector workers now belong to labor unions, and the number of new organizing drives continues to decline.4

There are reasons to hope that this trend could be slowed—or even reverse itself—if the labor movement changed its business model to digitally market directly to millions of workers who want more clout in the workplace. A prime target for such digital marketing campaigns are the nation’s millennial workers. Millennials are now the largest generation in the labor force, as of 20165—and 68 percent of them support labor unions.6 And overall, recent polls show that nearly half of workers say that they would join a union, if they could.7

The Challenge

Labor organizers currently face significant challenges in increasing labor density across the country, mostly because of the high cost of traditional labor organizing and especially for smaller bargaining units. Today’s unions continue to operate much the same way they did seventy-five years ago, relying primarily on a “retail” model, in which professional organizers work intensely with each workplace, hoping to convince a majority of workers to join the union. This retail model is resource-intensive, however, and so when union organizers do their cost-benefit analysis, they typically will target creating larger bargaining units rather than small ones.

What the labor movement needs today—short of sweeping new federal legislation to reform our labor laws—is a way to improve the economics of winning new, dues-paying members, thereby allowing unions to more easily organize bargaining units of all sizes, and especially smaller ones. It needs a business model that allows its organizers to reach out to potential union members where they are—including those in high-success, small bargaining units—in a cost effective way.

The key to this strategy is to directly empower workers to self-initiate organizing drives both large and small through a digital platform—one that not only provides workers with the information they need to begin an organization drive, but also walks them through the steps needed to win recognition, including getting coworkers’ signatures and filing paperwork at the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB). Furthermore, this new platform should be promoted through modern, digital marketing campaigns. Not only would such a strategy lower the cost of organizing by putting self-help organizing tools directly in the hands of millions of workers, but it would also allow unions to reach into workplaces that were once considered too geographically remote or too small to be cost-effective for traditional organizing drives.

For example, bargaining units of twenty-four or fewer employees are 11.6 percent more likely to win a union election than larger groups, and these employees consistently demonstrated more cohesion in their vote in support of the union.

This report begins with a brief look at the challenges that today’s workers face in forming a union, including the overall downward trend in the number of elections for union representation. It continues with an analysis of NLRB data that shows precisely where unionization is the most likely to succeed—in workplaces where employees coalesce into smaller bargaining units. For example, bargaining units of twenty-four or fewer employees are 11.6 percent more likely to win a union election than larger groups, and these employees consistently demonstrated more cohesion in their vote in support of the union.

The report then makes the case for reaching these workers through a digital marketing strategy, including by outlining the key features that a digital platform for organizing should have.

The Workers Who Want to Organize—and the Challenges of Organizing Them

Today, tens of millions of employees are seeing their economic condition decline, including an unprecedented squeeze of their checkbooks, courtesy of flat wages and escalating costs of housing, health care, and college. Stunning wealth inequality, with the richest 1 percent of families now owning 38.6 percent of America’s wealth (twice as much as the bottom 90 percent), is becoming normalized.8 Top-wage earners now make over five times the amount of low-wage earners, the largest gap in forty years.9 During the past few years, even as productivity and employment increased, wages for workers remained flat.10 Commentators Jacob Hacker and Paul Pierson have attributed rising inequality to lower unionization rates,11 and one study estimates that up to one-third of income inequality for men can be attributed to the decline in unions, and up to one-fifth for women.12

There are workers trying to buck this economic trend. Hidden away in the backwater of the NLRB website is a kind of honor roll of employees fighting for a more powerful voice at work to win better wages and benefits by petitioning the NLRB to be represented by a labor union.13

While the public’s attention is typically focused on large, high-stakes labor organizing drives—such as the 2014 UAW battle at the Volkswagen plant in Chattanooga, Tennessee,14 or the more recent effort by thousands of production and maintenance workers at a Nissan auto plant in Canton, Mississippi15—most successful organizing drives involve significantly fewer employees (a median size of twenty-six) and rarely receive media attention.16

For example, recent petitions filed with the National Labor Relations Board over the past year or so include fifteen employees at the Loews Hollywood Hotel, California, including maintenance engineers and painters, or the twenty-seven pyrotechnical workers at Disneyland Resorts, California, who put on their fireworks displays each day. Recent petitions also include some fifty cooks, waiters, servers, dishwashers, and table cleaners at the Saltus River Grill, in Beaufort, South Carolina, or the dozens of legal assistants, law clerks, staff attorneys, and paralegals and the Immigrant Defenders Law Center in Los Angeles, California.

The Century Foundation report “Virtual Labor Organizing” showed how the ability of employees to join a labor union is the single largest unclaimed legal right to additional personal wealth in the United States today, establishing the strong correlation between union participation and higher earnings. For example, median earnings for a two-income, union family are $400 a week more than that of a non-union family. That adds up to more than a half million dollars in additional wealth over a lifetime.17 Extending that financial clout to more households is critical to combating wealth inequality and restoring the middle class.

Median earnings for a two-income, union family are $400 a week more than that of a non-union family.

While the rewards of unionizing are great, for workers, the path to obtaining them can be a difficult one to follow. Workers who want to be represented by a union must take the first step of filing a petition for an election with the NLRB, and the petition must demonstrate that they have the support of at least 30 percent of the workers in the proposed bargaining unit. This initial support can be demonstrated by the signing of cards, or even by employees sending emails expressing their consent.18 Defining bargaining unit membership can be challenging, too, as the employees must demonstrate that the unit they seek to create has a “community of interest”—such as being comprised of service delivery drivers for a wholesaler. The concept is somewhat flexible, in that the unit does not have to include only workers that have the exact same job—it just needs to include workers that are logically placed together. Once an election has been scheduled for this unit, workers can only win collective bargaining rights if a majority of them in the bargaining unit vote for the union.

Navigating through the complicated process of unionization is easier if you’ve done it before, which is the reason for labor’s retail model: skilled organizers know the rules, know how and when to file paperwork, and know what type of resistance employers may put up, and when. But this model has a weakness in that it is only cost-effective in forming larger bargaining units, typically in high population centers, and cannot reach a lot of workers out there who want to unionize.

Aggregating the information on individual petitions filed with the NLRB over the past decade shows where the retail model is weakest. Not surprisingly, geographically, unionization is centered around the coasts and the heartland, with sparse representation in the Great Plains and the South (see Map 1). Beyond the problem of pure enrollment numbers, this lack of geographical diversity presents another significant problem for the labor movement: some states lack the critical mass of unionized workers not only to promote union membership at their workplace, but also to advance worker rights in Congress and state legislatures.

Map 1. Size and Location of Union Election Petitions Filed with the NLRB, 2007–18

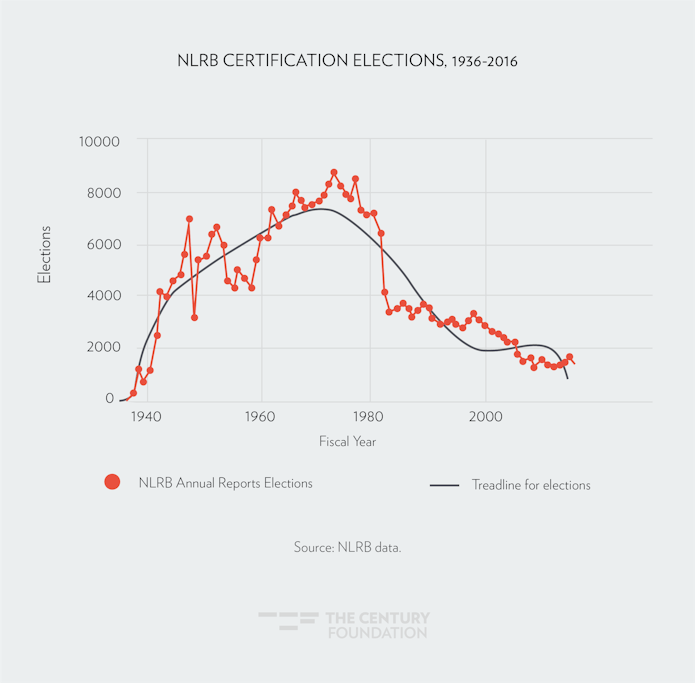

Table 1 indicates the number of representative petitions filed by labor unions is reaching all-time lows. In fiscal year 2018, only 1,597 petitions were filed with the NLRB, the fewest number of petitions filed in over seventy-five years (see Table 1 and Figure 1). Furthermore, over the past decade, the number of petitions filed with the board has averaged 2,200 per year—less than half the average number for the previous decade. The zenith of union activity was in the mid-1970s, with some some 9,000 elections certified; the number in 2018 was about less than one-tenth that high water mark, however, with only 790 successful union elections. This is consistent with long-term trends in labor, including a precipitous drop in election certifications seen in the 1980s, following President Reagan’s firing of striking air traffic controllers and the decertification of their union in 1981.

Table 1

| NLRB Election Petitions, 2008-18 | ||||||

| Petitions Filed | Elections Held | Won by Union | Lost by Union | Petitions Dismissed | Petitions Withdrawn | |

| FY08 | 2,418 | 1,614 | 1,028 | 586 | 48 | 784 |

| FY09 | 2,082 | 1,335 | 915 | 420 | 46 | 657 |

| FY10 | 2,380 | 1,571 | 1,036 | 535 | 37 | 725 |

| FY11 | 2,108 | 1,398 | 935 | 463 | 43 | 667 |

| FY12 | 1,974 | 1,348 | 868 | 480 | 38 | 597 |

| FY13 | 1,986 | 1,330 | 852 | 478 | 27 | 607 |

| FY14 | 2,053 | 1,407 | 952 | 440 | 24 | 586 |

| FY15 | 2,198 | 1,574 | 1,120 | 480 | 39 | 663 |

| FY16 | 2,029 | 1,396 | 1,014 | 401 | 38 | 610 |

| FY17 | 1,854 | 1,366 | 940 | 375 | 29 | 493 |

| FY18 | 1,597 | 1,120 | 790 | 330 | 17 | 386 |

| Source: NLRB data. | ||||||

Figure 1 shows a longer trends of union elections, showing the dramatic declines over the past forty years.

Figure 1

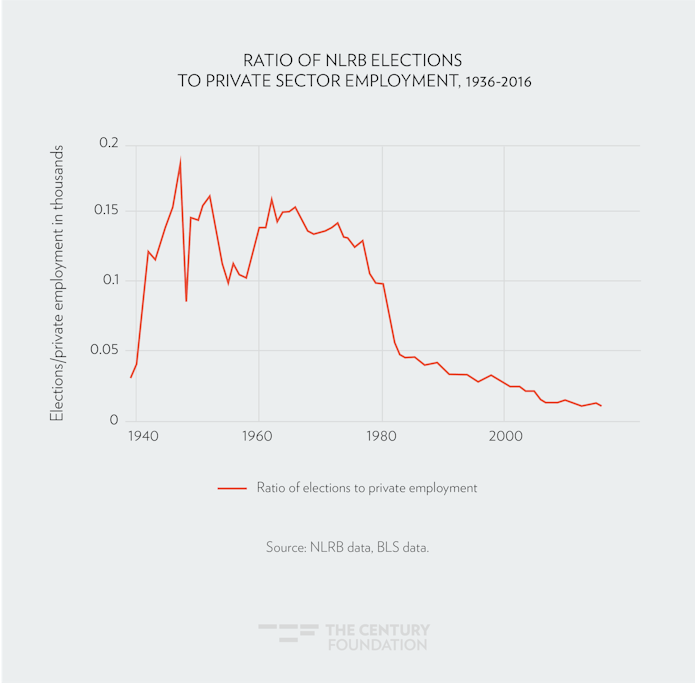

As Figure 2 shows, the ratio of NLRB elections to private sector employment has declined steadily since the late 1970s, and is now at its lowest level in history.

Figure 2

To punctuate how significant the decline of union elections and unionization has been relative to the growing workforce, we ran some simple “what-if” calculations. Had the ratio of union elections to private sector non-union employment stayed constant at its peak in 1973, 19,234 more elections would have been held in 2016, in addition to the 1,663 elections actually recorded.19 To translate, had the unionization rate in the private sector remained at 24 percent, as it was in 1973, as opposed to 6 percent in 2017, a remarkable 30 million workers would be unionized instead of merely 8 million.20

Where Unionizing Is Easiest: Smaller Workplaces

According to our analysis of NLRB microdata on union representation elections from April 2007 to December 2018, we find that small units are more likely to win elections—and win them by wider margins. In the past decade, thousands of workers have been unionized in small shops.

Table 2 shows the number of workers who became unionized during the period of 2007–18, and the number of successful elections by union size. Most workers are unionized in shops with fewer than 250 workers—431,656 in total during our study period. This is nearly double the number of workers unionized in units with 250 or more workers (260,498). Overall, 63 percent of elections result in union representation.21

Table 2

| Workers Unionized and Number of Election Certifications, 2007–18, by Unit Size | ||

| Unit Size | Thousands of Workers Unionized | Number of Elections Won |

| 1–9 | 15,169 | 2,789 |

| 10–24 | 47,188 | 2,957 |

| 25–49 | 75,354 | 2,148 |

| 50–99 | 121,548 | 1,731 |

| 100–249 | 172,397 | 1,140 |

| Subtotal | 431,656 | 10,765 |

| 250+ | 260,498 | 496 |

| Total | 692,154 | 11,261 |

| Source: Author analysis of NLRB election data. | ||

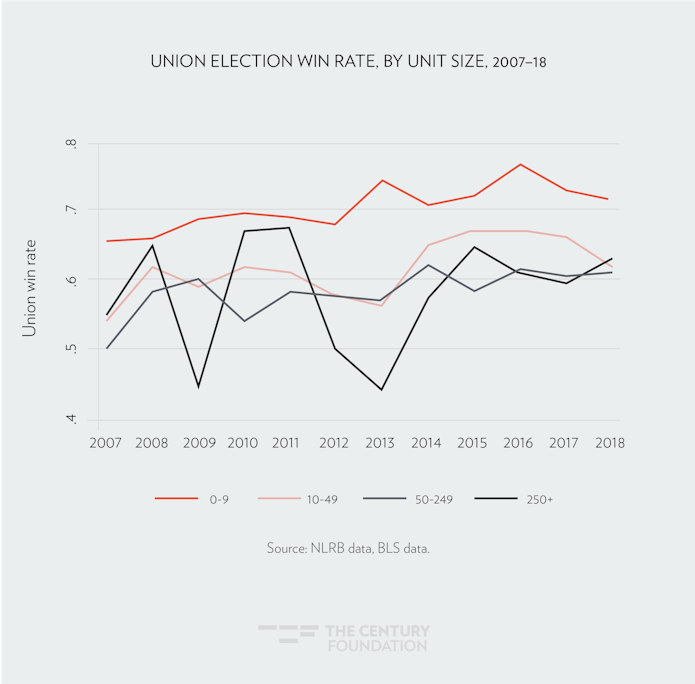

Smaller bargaining units also win a larger share of their NLRB union elections than their larger counterparts. For example, units with nine employees or under have a win rate of 70.6 percent compared with, say, bargaining units of 100–249 employees, which have a win rate of 56.8 percent. The outsized success of smaller units has been consistently true in recent years, as noted in Figure 3. While very large units (250+ employees) are sometimes more successful than midsize ones, their results are volatile, due to the relatively small number of elections of such scale.

Figure 3

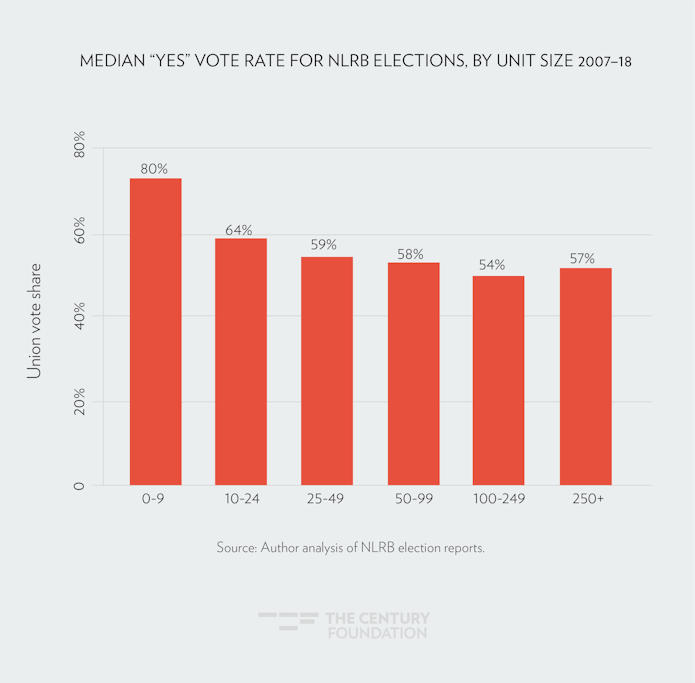

Figure 4 reports the median “yes” vote rate by establishment size. The data makes the relationship clearer: the smaller the unit, the larger share of the unit votes for a union. In the typical small-unit election, unions win 80 percent of the vote. Unions win nearly two-thirds of the vote among typical elections for units of 10–24 employees; this drops to under 60 percent for larger units.

Figure 4

It is noteworthy that, even though unions generally have more success with smaller bargaining units, the percentage of union density among smaller employers is much lower. As shown in Table 3, employers with under twenty-five employees have unionization rates under 5 percent, compared to an average of over 15 percent or more for employers with over 250 employees. It suggests there is a good deal of opportunity for unions and workers to increase density among smaller establishments.

Table 3

| Percentage of Unionized Employees, by Establishment Size, April 2001 | |||||||

| All Firms | Unweighted tabulation of establishments (percentage) | Employee-weighted tabulation of establishments (percentage) | |||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

| Sample Size | % of Employees in a Union | % of Employees in a Union | |||||

| >0 | 0 to 50 | >50 | >0 | 0 to 50 | >50 | ||

| 21,854 | 6.53 | 2.83 | 3.61 | 20.85 | 10.33 | 10.33 | |

| By Establishment Size | |||||||

| <10 employees | 10,426 | 2.34 | 1.10 | 1.23 | 2.62 | 1.14 | 1.47 |

| 10 to 24 employees | 5,532 | 4.66 | 2.19 | 2.40 | 5.73 | 2.99 | 2.70 |

| 25 to 49 employees | 2,360 | 8.81 | 3.43 | 5.34 | 10.81 | 4.36 | 6.44 |

| 50 to 99 employees | 1,483 | 14.11 | 6.00 | 7.82 | 19.07 | 6.83 | 12.10 |

| 100 to 249 employees | 1,249 | 20.78 | 7.13 | 12.89 | 23.53 | 7.34 | 15.92 |

| 250 + employees | 779 | 31.50 | 15.53 | 15.79 | 38.25 | 23.23 | 14.97 |

|

Note: There are 25 establishments for which it is possible to determine the presence of a union but not the percent of workers who are members. Because of this (and rounding), the second and third column of each panel (columns 3–4 and 6–7) may not sum to equal the first (columns 2 and 5). Source: Thomas, C. Buchmueller, John Dinardo, Robert G. Valletta, “Union Effects on Health Insurance Provision and Coverage in the United States,” National Bureau of Economic Research, February 2002, Table 2, https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Establishment-Union-Density-by-Establishment-Size-RWJF-Data_tbl3_5119479. |

|||||||

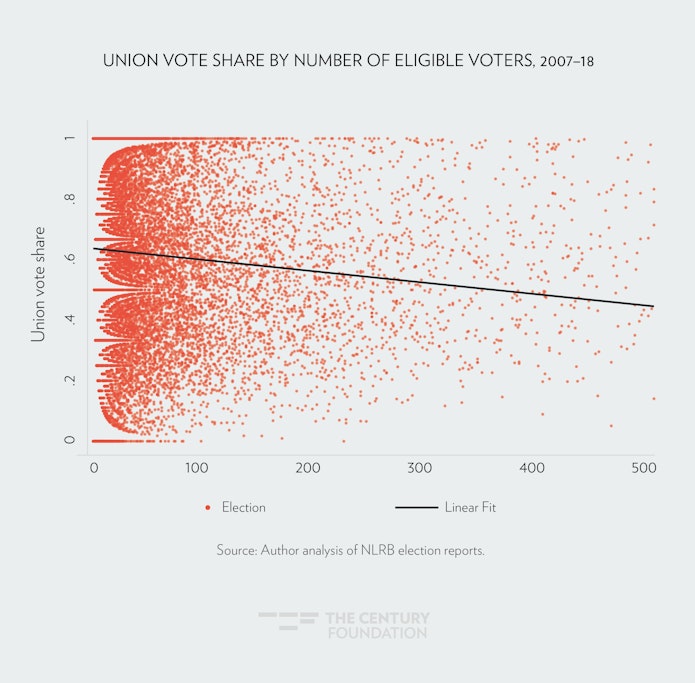

Figure 5 shows the relationship between the number of eligible voters and share of “yes” votes in the representation election. Each data point represents an NLRB union election where there were 1 to 500 eligible workers, from 2007 to 2018.22 The figure shows an inverse relationship between union vote shares and the number of eligible voters per election (a proxy for unit size).23

Figure 5

It should be noted that many factors can affect the outcome seen here. Differences between election characteristics—where the election happened, what NLRB regional office oversaw the election, when the election was held, and who the employer was—all can have an effect on the outcome of the election.

Through regression analysis, however, we can control for differences in employers, location, and date. Results show smaller bargaining units—those with twenty-four or fewer workers—are 11.6 percent more likely to win a union election than larger units.24

Smaller bargaining units—those with twenty-four or fewer workers—are 11.6 percent more likely to win a union election than larger units.

The higher rate of success for small bargaining units is an important data point for union strategy for building membership. Success may be higher because employees are more cohesive, and can more easily withstand employer pressure. Although there are often small bargaining units within larger employers, those at small establishments may face employers with less resources to resist an organizing drive, and there may be fewer legal issues, such as the composition of the unit, against which the employers could launch legal objections.

The biggest challenge for unions in prioritizing high-success but smaller bargaining units is the relative inefficiency of organizing them. The traditional strategy of sending in labor organizers to identify targets of opportunity, build an organizing committee, educate employees, and prepare for an election takes significant resources when organizing smaller bargaining units, despite their greater success rate.

The next section, however, suggests that sophisticated digital technology can be deployed to make organizing drives significantly more cost-effective, for small and large bargaining units alike. By empowering workers to do more of the initial organizing drive using a digital platform, and mass promoting this platform to a large number of employees through targeted digital marketing, unions can extend their reach into more workplaces across the country, both large and small.

Creating a New Business Model: Digital Organizing

As noted above, the current trajectory for labor union membership is downward, with declining election petitions and a declining share of workers who belong to union. But the labor movement’s higher success rate organizing smaller bargaining units suggest that two strategies could help reverse some of labor’s decline: a strategic direct marketing campaign to encourage, educate, inspire, and assist workers to join a union; and a state-of-the-art digital platform to allow workers moved by the digital campaign to take decisive action on their own.

The use of sophisticated digital technology in issue-oriented campaigns is not a new thing, and in fact, political campaigns are already exploding with new, landmark data mining tools—but unions have been late to the game in using advanced technology.25 The authors of a recent article in the Internet Policy Review carefully analyzed the rapid advance in digital political campaign tools and concluded that “electoral politics has now become fully integrated into a growing, global commercial digital media and marketing ecosystem that has already transformed how corporations market their products and influence consumers.”26 Sophisticated data mining and “significant breakthroughs in data-driven marketing techniques, such as cross-device targeting” allows campaigns to identify, engage and influence sympathetic voters. They can deliver very specific messaging across mobile devices, even launching “at specific times when they may be more receptive to a message.”

The article concludes:

Political databases hold records on almost 200 million eligible American voters. Each record contains hundreds if not thousands of fields derived from voter rolls, donor and response data, campaign web data, and consumer and other data obtained from data brokers, all of which is combined into a giant assemblage made possible by fast computers, speedy network connections, cheap data storage, and ample financial and technical resources.27

Digital marketing would allow unions to directly contact millions of current employees to provide them with information about joining a union, and the tools to take decisive action on their own. Algorithms and targeting tools proven effective in commercial and political campaigns could be deployed to find and assist employees who are willing to take action to help organize the workplace. For example, the use of big data analytics now can use “lookalike modeling” to create profiles of existing union members (perhaps based on income, culture, religion, age, religion, political beliefs, other interests), and then identify similar workers are not in a union, yet who might be good prospects for joining one. Programmatic advertising similar to that now used for political campaigns can then reach people with these profiles through automated forms of ad buying and placement on digital media.

What if an algorithm that could identify the ten Beto O’Rourke volunteers who also work in retail stores in El Paso, and could invite them all to a meet-up to discuss launching a campaign for better wages, or an organizing drive?What if a worker used “low pay” as a search term, and in response, contact information for five union locals popped up, along with a link to a digital organizing tool? What if low-wage individuals working in the food service or retail sector received ads promoting union membership on Facebook and Instagram, instead of promotions hawking high interest credit cards?

While leveraging big data has raised privacy concerns, the truth is that today it is already an essential part of the playbook deployed by our nation’s most powerful corporations. Workers are already targets of big data, in ways that run counter to their interests: employers are currently using big data in all aspects of employment, including hiring, on-the job monitoring, and productivity and wellness tracking. This use of big data in the workplace—what has been called the “datafication of employment” in a recent TCF report28—is increasingly tilting the playing field in favor of employers. The report—citing a study by Deloitte29—notes that 71 percent of companies now prioritize “people analytics” and HR data for recruitment and workforce management.

If the labor movement wants to survive and thrive in this environment, it cannot cede ground in the big data game. It must deploy digital marketing techniques now being used by powerful commercial and political players, or it will fail. Here are five reasons why the arrival of a digital organizing platform—backed up with targeted marketing—has the potential to be successful.

- Digital technology is ready-made to mobilize younger workers. Younger workers—including strongly pro-union millennials—have grown up using online tools to navigate their lives, and probably would more readily embrace a digital tool for organizing. A recent blog post by the California Labor Federation entitled “Millennials and the Unions: A Match Made in Heaven” notes opportunities millennials bring to revitalizing the labor movement.30 Millennials strongly support unions as a cohort, and some three-quarters of new union members are under the age of thirty-five.31

- Digital technology may be especially effective in organizing small- and medium-size bargaining units. Smaller groups of employees have fewer challenges in organically organizing and communicating among themselves; in staying united in the face of employer opposition; and, as documented above, are generally more successful in winning elections. Organization drives by smaller groups of employees may face fewer legal challenges by employers, such as disputes regarding the nature of the bargaining unit.33

- Peer-to-peer interaction is more likely to rebuild cultural acceptance of unions in the workplace. Although it is true that opinion polls suggest majority support for labor unions, the truth is that most private sector workers have little direct experience with union shops, union members, or union organizers. Organic action by rank-and-file workers, promoted on social media and cultivated through a digital platform, has the potential to win over workplaces that on-the-ground union organizers traditionally have not been able reach, and to build the grassroots power that is essential for a revival of the labor movement.

- Some employers may react better to organic efforts by employees to organize a workplace. In union campaigns, some employers use the argument that employees are acting at the behest of outsiders, such as “big labor” or “outside organizers,” who they claim do not have the employees’ interests at heart. Organic organizing makes it clear from the start that the employees are initiating the organizing drive and advocating for better working conditions on their own behalf, even if they later bring in a union to help execute their organizing efforts.

Today, most employers may not view the possibility of unionization as a likelihood, because so few establishments are organized. If employers understood that employees have access to a powerful, new tool to assist in the launching of organizing, they may be more sensitive to employee concerns far in advance of such a drive. This could induce may employers early on to self-initiate better benefits and working conditions to avoid future organization drives.

The Platforms That Exist—and the One That Should Be Built

Despite the advance of digital technology that has revolutionized consumer purchasing, social media, health care, transportation, entertainment, learning, news, and scientific research, there are no user-friendly, specialized digital technologies available to help workers to launch an organizing campaign on their own and see it through to the recognition of their union.34

The only existing digital labor organizing tool that comes even close is an online election petition, sponsored by the NLRB itself.35 Buried in the back pages of the NLRB website, it allows employees to start a union petition by answering fifteen online questions for basic information. These questions include the nature and location of their employer, a description and number of employees in the proposed bargaining unit, whether the employees are affiliated with a union, whether there is a strike or picketing underway, and whether the employees are asking for a mail-in or in-person election.Although beginning a labor organizing campaign has been made to seem an arduous task, mostly because of the abusive legal tactics of employers, the actual mechanics of filling out a union petition are fairly straightforward. Most smaller groups of employees could fill this form out in fifteen minutes or less.

The only existing digital labor organizing tool that comes even close is an online election petition, sponsored by the NLRB itself.

The NLRB’s online platform, however, is deeply flawed. It lacks the interactive/real-time assistance features of most rudimentary online tools or apps, does not support features for employees to speak with each other, and has never even been promoted to the public by the NLRB or by the labor community. As noted in TCF’s report, “Virtual Labor Organizing,” a well-designed platform would provide an “interactive, step-by-step process so that employees know what to expect at each stage, and how to handle hurdles that may arise.”36

There are many reasons that labor unions have been slow to adopt and integrate new technology in organizing. Some union locals often lack resources and expertise to deploy new technology. Also, there is skepticism among professional organizers whether digital tools can ever be the primary way in which workers initiate and carry out organizing drives, even for smaller bargaining units. As one organizer explains, people are not moved by online communications alone, they require face to face communications to win them over: “When you look someone in the eyes and ask them to be with you, that’s when they say yes.”37 Even beyond the confidence and team-building support a professional organizer brings to a campaign, labor officials will point out that in the face of efforts by employers to sabotage employee organizing drives through retaliatory actions, misstatements, intimidation, threats, abuse of NLRB procedures, and filibustering on first contracts—efforts that have been well-documented for decades—workers need access to experienced organizers and aggressive legal support to combat repeated employer roadblocks.

While some skepticism is warranted about the prospects of remotely empowering employees to begin and advance their own organizing drive, there already are examples where organizers have used social media and other digital tools as part of their efforts to help workers run issue campaigns against employers. The landmark Fight for $15 campaign, for example, smartly used social media to push for higher wages in the fast food industry. Coworker.org has a powerful online platform for workers running issue campaigns, and its winning feature is that it empowers groups of workers to select and launch an issues campaign without approval or mediation from Coworker. The Coworker initiative even integrates other social media platforms for maximum impact, and effectively uses online advocacy petitions, information sharing, and protest actions.38 While some employees have used the Coworker platform to help collect signatures for an NLRB petition—such as Capital Bikeshare in Washington, D.C.—it is not designed to transform issue campaigns into union organizing drives.39

There are online tools for organizing—such as Broadstripes and NationBuilder—that are helpful for mapping out the workplace and keeping track of employee contacts and supporters, but they are tools built for professional organizers, not rank-and-file workers to launch a petition drive.40 Some employee groups have launched Facebook groups, which have some level of protection for members because comments are limited to group members. For example, delivery employees at Instacart organized a “no delivery day” through Facebook over wages, and flight attendants keep updated on contracts and work rules of various airlines through a Facebook group.41

While these digital efforts and platforms are helping to empower workers, none of them are primarily designed for employees to initiate and carry forward an organizing drive primarily on their own, from beginning to end.

While these digital efforts and platforms are helping to empower workers, none of them are primarily designed for employees to initiate and carry forward an organizing drive primarily on their own, from beginning to end—which means that the vast majority of workplaces that want to organize still are unable to cross the finish line without substantial assistance from a professional organizer. What is needed is a tool that can extend the reach of labor into workplaces where current organizing efforts have been unable to reach.

The essential element for this new tool is a step-by-step process that ultimately allows willing employees to take formal action, filing for an election or seeking voluntary recognition from the employer. Its overall purpose is to empower, simplify, and demystify the federal legal right of employees to consider and then vote on whether to join a union.

In terms of the key attributes for an online organizing platform, it should be able to:

- Help workers find a union local. The platform should have at the very least an easy to search list of union locals in the area that could assist the employees in an organizing drive and then affiliate with the employees, complete with information for online and direct contact.

- Provide interactive help in starting an organizing effort. The platform should have interactive tools that provide additional information on key topics, such as how to lawfully engage with other employees, how to educate employees about joining a union, how an election is conducted by the NLRB, how to ask for voluntary recognition, and how to respond to any unlawful activities of the employer. Unions frequently provide this standard advice on their websites, but it requires that workers know how to find it; the digital world is now filled with interactive tools that can provide more refined, situation-specific guidance.

- Drive employees to formally request a union election when ready. At its basic level, an organizing drive is simply a push to have to have an election for workers to vote on whether they want to join a union. The platform should have as a central feature the ability to trigger the election stage quickly, once there appears to be sufficient support. To encourage this outcome, the platform should have the capability to fill out and submitting the NLRB petition form as well as collecting the necessary signatures from interested coworkers.

- Enable workers to complete the process on their own, yet provide assistance if needed. The platform should be designed to help employees advance as far in the initial organizing campaign that they feel comfortable with. That is the only way to make the organizing process more efficient for unions, and bring organizing efforts to scale. However, employees facing abusive employer conduct must be able to access online and direct call assistance. Platform tools could also have lists of volunteers at nearby unionized shops who are willing to share experiences, and give advice.

- Facilitate communications with fellow employees. The platform should link to existing tools to communicate with other employees, depending on the level of confidentiality desired. While legal rulings have permitted employees to use work email systems to communicate on union issues, the Trump administration–controlled board may modify that right.42

Conclusion

There is no doubt that revitalizing the labor movement with advanced digital tools is a significant challenge. Decades of aggressive union-busting tactics by businesses has significantly raised the friction and risk for workers who want to organize their workplace. The report by the House Education and Labor Committee that accompanied the House passage of the Employee Free Choice Act in 2007 carefully documented this sustained and relentless assault on worker rights:

For more than 70 years, workers’ freedom to organize and collectively bargain has depended upon the effectiveness of the NLRA. Today, the NLRA is ineffective, and American workers’ freedom to organize and collectively bargain is in peril everyday as a result. The numbers are staggering. Every 23 minutes, a worker is fired or otherwise discriminated against because of his or her union activity. According to NLRB Annual Reports between 1993 and 2003, an average of 22,633 workers per year received back pay from their employers. In 2005, this number hit 31,358.8 A recent study by the Center for Economic and Policy Research found that, in 2005, workers engaged in pro-union activism ‘‘faced almost a 20 percent chance of being fired during a union-election campaign.’’ The number of workers awarded back pay by the NLRB also reveals a worsening trend. The NLRB provides backpay to workers who are illegally fired, laid off, demoted, suspended, denied work, or otherwise discriminated against because of their union activity. In 1969 a little over 6,000 workers received backpay because of illegal employer actions. That number has risen by 500 percent although the percentage of the private sector workforce that is unionized has declined over the same time period from nearly 30 percent to just 7.4 percent. In the 1970s, 1-in-100 pro-union workers actively involved in an organizing drive was fired. Today, that number has doubled to about 1-in-53. The anti-union activities of employers have become far more sophisticated and brazen in recent history. Today, 25 percent of employers illegally fire at least one worker for union activity during an organizing campaign. Additionally, 75 percent of employers facing a union organizing drive hire anti-union consultants. During an organizing drive, 78 percent of employers force their employees to attend one-on-one meetings against the union with supervisors, while 92 percent force employees to attend mandatory, captive audience anti-union meetings. More than half of all employers facing an organizing drive threaten to close all or part of their plants.43

Many of the first, brave wave of workers to launch digital organizing drives will face fierce employer resistance, and maybe even initial skepticism from some coworkers. Some workers will end up putting their jobs on the line, and some will need legal and moral support to fight unlawful discrimination or retaliation. It is a painful truth that, historically, the success of the nation’s labor movement, like the civil rights movement, only prevailed through the courageous and hard-fought—and sometimes deadly—sacrifice of many heroic workers and advocates.

In the final analysis, the only way to really fight massive employer resistance to union organizing is to normalize union membership using powerful countermeasures. There must be massive, locally initiated organizing actions spreading across the country like wildfire. As scholar and former organizer Jane McAlevey has observed, “only true organic leaders can lead their coworkers in high risk action.”44 Winning elections at the workplace is a confidence game. It is a psychological contest with high stakes, because it seeks to disrupt the balance of power at work. Scale and community reaction are likely to be the determining factors in its success. Like the powerful progress of the #MeToo movement, launched to counter the nation’s devastating failure to address discrimination, abuse, and sexual assault, we can also send the message that it is simply not okay to abuse workers who are just exercising their lawful right to organize a union. Digital platforms—backed by a targeted, massive, direct marketing campaign and legal support—can challenge pernicious, abusive treatment of workers.

Workers across the country need more leverage at work to win fairer wages, benefits, and working conditions. This report demonstrates that smaller groups of workers seeking unionization have higher rates of success. New digital tools and marketing, geared initially toward smaller bargaining units, may be a cost effective way to build union membership, but such a strategy must be tested for effectiveness.

A new generation is called upon to reclaim the worker voice. Millennials, perhaps more fearless in asserting their rights at work, more supportive of the labor union mission, and more comfortable with using powerful, new digital communications and social networks, may be the “match made in heaven” to rewrite existing norms and to insist on more respect and dignity at work.

They should be given all the support that the labor movement and its allies can muster, starting with a well-designed, sophisticated digital organizing strategy worthy of the challenge they face.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Mike Cassidy and Michael McCormack for their extensive help in collecting and analyzing data on the impact of collective bargaining unit size for this report.

Please see the downloadable PDF for appendix.

Notes

- See, for example, Jack Milroy, “The list makes us strong. Why unions need a digital strategy,” Medium, April 29, 2016, https://medium.com/@jack_milroy/the-list-makes-us-strong-why-unions-need-a-digital-strategy-42291213298a.

- Tom Liacas, “Fight for $15: Directed-network campaigning in action,” Mob Lab, September 8, 2016, https://mobilisationlab.org/fight-for-15-directed-network-campaigning-in-action/.

- Rick Wartzman, “American Workers Try to Organize—One Click at a Time,” Forbes, February 16, 2016, fortune.com/2016/02/16/workers-group-our-walmart-use-tech-to-organize/; David Moberg, “The Union Behind the Biggest Campaign Against Walmart in History May Be Throwing in the Towel. Why?” In These Times, August 11, 2015, inthesetimes.com/article/18271/which-way-our-walmart; Peter Olney, “Where Did the OUR Walmart Campaign Go Wrong?” In These Times, December 14, 2015, inthesetimes.com/working/entry/18692/our-walmart-union-ufcw-black-friday.

- See, for example, Mark Zuckerman, Richard D. Kahlenberg, and Moshe Marvit, “Virtual Labor Organizing: Could Technology Help Reduce Income Inequality?” The Century Foundation, June 9, 2015, https://tcf.org/content/report/virtual-labor-organizing/.

- Richard Fry, “Millennials are the largest generation in the U.S. labor force,” Pew Research Center, April 11, 2018, https://www.google.com/amp/www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/04/11/millennials-largest-generation-us-labor-force/%3Famp%3D1.

- “Millennials and Unions: A Match Made in Heaven,” California Labor Federation, June 25, 2018, https://calaborfed.org/millennials-and-unions-a-match-made-in-heaven/.

- “A Growing Number of Americans Want to Join a Union,” PBS NewsHour, September 3, 2018, https://www.google.com/amp/s/www.pbs.org/newshour/amp/nation/a-growing-number-of-americans-want-to-join-a-union.

- Federal Reserve Bulletin, Evidence From Survey of Consumer Changes in Finances: U.S Family Finances from 2013 to 2016, https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/scf17.pdf

- Sho Chandra and Jordan Yadoo, “U.S. Wage Disparity Took Another Turn for the Worse Last Year,” Bloomberg, January 26, 2017, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-01-26/u-s-wage-disparity-took-another-turn-for-the-worse-last-year.

- Real Earnings, September 2017,” U.S Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, October 13, 2017, https://www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/realer_10132017.pdf.

- Hacker, Jacob S. and Paul Pierson. 2010. Winner-Take-All Politics: How Washington Made the Rich Richer— And Turned Its Back on the Middle Class (New York: Simon and Schuster).

- Bruce Western and Jake Rosenfeld, “Unions, Norms, and the Rise in U.S. Wage Inequality,” American Sociological Review 76, no. 4 (2011): 513, http://www.asanet.org/sites/default/files/savvy/images/journals/docs/pdf/asr/WesternandRosenfeld.pdf.

- See the NLRB website for recent petitions filed: https://www.nlrb.gov/news-outreach/graphs-data/recent-filings?f[0]=ct%3AR.

- Lydia DePillis “Auto union loses historic election at Volkswagen plant in Tennessee,” Washington Post, February 14, 2014, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2014/02/14/united-auto-workers-lose-historic-election-at-chattanooga-volkswagen-plant/.

- Noam Scheiber, “Nissan Workers in Mississippi Reject Union Bid by U.A.W.,” New York Times, August 5, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/05/business/nissan-united-auto-workers-union.html.

- “Median Size of Bargaining Units, FY 09 to FY 18,” NRLB, https://www.nlrb.gov/news-outreach/graphs-data/petitions-and-elections/median-size-bargaining-units-elections.

- Mark Zuckerman, Richard D. Kahlenberg, and Moshe Marvit, “Virtual Labor Organizing: Could Technology Help Reduce Income Inequality?” The Century Foundation, June 9, 2015, https://tcf.org/content/report/virtual-labor-organizing/.

- See “What steps are required in order to file a petition with the NLRB to certify or decertify a union?” National Labor Relations Board, https://www.nlrb.gov/resources/faq/initial-processing/what-steps-are-required-order-file-petition-nlrb-certify-or.

- These estimates were calculated by multiplying the non-union private sector employment in 2016 by the election-to-employment ratio and the election-votes-to-employment ratio in 1973.

- BLS and unionstat data.

- Our data consists of 17,888 elections compiled from NLRB election reports. Our sample includes all cases closing from April 20, 2007 through December 31, 2018, for which election tally dates occurred after 2007. Re-run, run-off, and decertification /elections are excluded; cases lacking election type information (September 2017 to December 2018) are presumed to be initial non-decertification elections and are all included. Elections with union vote shares in excess of 100 percent or where vote counts exceed the number of eligible voters are excluded.

- To eliminate outliers, 501 workers was set as the maximum value: the unit size of the 99th percentile in the distribution was 501 workers.

- We see that many elections are clustered below the 200-worker mark, while the scattered elections among higher units appear more likely to fail. Smaller units also have packets of elections where the Union Yes ratio is at certain percentages. This is because with fewer workers in a unit, the Union Yes ratio can only take a discrete set of values. For example, a unit of three workers can only have four possible vote shares: 0 percent, 33.3 percent, 66.6 percent and 100 percent. This explains why many elections for small units cluster around certain values (0 percent and 100 percent for example), as well as the curved “humps” seen on the far left of the plot.

- See the appendix for regression results and a discussion of methodology.

- Kati Sipp, “The Internet vs. the Labor Movement: Why Unions Are Late-Comers to Digital Organizing,” New Labor Forum, April 2016, https://newlaborforum.cuny.edu/2016/04/30/internet-versus-the-labor-movement/.

- Jeff Chester and Kathryn C. Montgomery, “The role of digital marketing in political campaigns,” Internet Policy Review 6, no. 4 (2017), https://policyreview.info/articles/analysis/role-digital-marketing-political-campaigns.

- Jeff Chester and Kathryn C. Montgomery, “The role of digital marketing in political campaigns,” Internet Policy Review 6, no. 4 (2017), https://policyreview.info/articles/analysis/role-digital-marketing-political-campaigns.

- Sam Adler-Bell and Michelle Miller, “The Datafication of Employment: How Surveillance and Capitalism Are Shaping Workers’ Futures without Their Knowledge,” The Century Foundation, December 19, 2018, https://tcf.org/content/report/datafication-employment-surveillance-capitalism-shaping-workers-futures-without-knowledge/.

- Laurence Collins, David R Fineman, Akio Tsuchuda, “People analytics: Recalculating the route,” Deloitte 2017 Global Human Capital Trends, February 28, 2017, https://www2.deloitte.com/insights/us/en/focus/human-capital-trends/2017/people-analytics-in-hr.html.

- Alexandra Catsoulis, “Millennials and Unions: A Match Made in Heaven,” California Labor Federation, June 25, 2018, https://calaborfed.org/millennials-and-unions-a-match-made-in-heaven/.

- Center for Economic and Policy Research, January 2018, Union Membership 2018, page 7.

- See definition of a “community of interest” in “Basic Guide to the National Labor Relations Act General Principles of Law Under the Statute and Procedures of the National Labor Relations Board,” National Labor Relations Board, 1997, 13, https://www.nlrb.gov/sites/default/files/attachments/basic-page/node-3024/basicguide.pdf. [/note}

- Digital technology could substantially lower the cost of union organizing. Labor unions lack the resources to undertake a massive new effort to organize workplaces across the country. Under the traditional model, unions send organizers to help build support for a union, educating workers and intervening if there are employer violations such as retaliatory actions, coercion, or threats. A goal of digital technology is to lower the cost of organizing each workplace by empowering workers to do much of the early organizing themselves, by communicating with and winning the support of their coworkers, and by filing elections petitions. Unions could operate more efficiency if they can link up with groups of workers who already came to the decision to unionize, and who have already developed the solidarity required to see a union drive through to its conclusion. Indeed, many models of labor organizing involve creating an organizing committee before proceeding to an election or union drive.32“How to Organize,” Communications Workers of America, https://www.cwa-union.org/join-union/how-organize.

- Digital technologies have successfully been developed to assist with legal processes, such as Turbotax and LegalZoom, that are highly interactive with direct help for special problems.

- See the NLRB website, https://apps.nlrb.gov/chargeandpetition/#/questions/3.

- Mark Zuckerman, Richard D. Kahlenberg, and Moshe Marvit, “Virtual Labor Organizing: Could Technology Help Reduce Income Inequality?” The Century Foundation, June 9, 2015, https://tcf.org/content/report/virtual-labor-organizing/.

- #1u Digital Training: Online to Offline,” AFL-CIO Digital Strategies, June 24, 2013, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qOW0ixgrsYM.

- For example an employee at Comcast started a petition drive to get the company to take more decisive action against sexual harassment at the company, and collected over 4000 signatures.# Disney workers are using Coworker.org to urge the company to pass on a portion of its huge federal tax cut to boost employee wages, and technology workers from IBM and Oracle employees used Coworker to #promote more diversity and inclusive work policies.

- “Digital Workers, Digital Organizing,” ILR School, Cornell University, October 5, 2017, http://www.cornell.edu/video/digital-workers-digital-organizing-coworker-org.

- See their websites, http://www.broadstripes.com/ and https://nationbuilder.com/.

- Annalisa Nash Fernandez, “Facebook groups are the new workers’ unions,” Quartz, December 6, 2017, https://qz.com/1145658/facebook-groups-are-the-new-workers-unions/.

- Josh Eidelson, Hassan Kanu, and Mark Bergen, “Google Urged the U.S. to Limit Protection for Activist Workers,” Bloomberg, January 24, 2019, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-01-24/google-urged-the-u-s-to-limit-protection-for-activist-workers.

- Report of the U.S. House Education and Labor Committee, The Employee Free Choice Act of 2007, 100-23, https://www.congress.gov/110/crpt/hrpt23/CRPT-110hrpt23.pdf.

- Jane F. McAlevey, No Shortcuts: Organizing for Power in the New Guilded Age (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), 37.