This testimony was prepared for a hearing of the House Education and Workforce Committee, Subcommittee on Workforce Protections, held on February 16, 2017. The testimony was prepared in advance of the hearing, before the subsequent withdrawal of labor secretary nominee Andrew Puzder.

Good morning, Chairman Byrne, Ranking Member Takano, and other members of the Committee. Thank you for the opportunity to speak to the Committee today about the changing nature of the economy and the need to modernize the protections under the Fair Labor Standards Act. I am a Senior Fellow at the Century Foundation, an independent nonpartisan think tank with offices in Washington and New York City.

The Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) of 1938 provides a basic floor on fair treatment for workers in the U.S. economy. It has led to, among other things, a federal minimum wage of $7.25 per hour, and the right to time-and-a-half pay for work beyond forty hours per week, as well as improvements in child labor law. I am pleased to have this opportunity to discuss the changing nature of the economy and some key policy changes that could increase the effectiveness of the Act.

- For decades, Americans have been afflicted by stagnating wages and a rise in low-wage work—and corporations not workers have enjoyed the fruits of the current economic recovery. The Fair Labor Standards Act could be a powerful lever against wage stagnation—if Congress were to significantly increase the minimum wage, eliminate the sub-minimum wage for tipped workers, and strengthen overtime protections for the middle class.

- The twenty-first century has accelerated changes to the structure of work that have left workers’ wages more vulnerable to theft than ever before, and the Department of Labor needs to pair aggressive targeted enforcement with thoughtful policy guidance on issues like misclassification and joint employment.

- The Fair Labor Standards Act is already able to respond to a variety of flexible arrangements, like telework and the gig economy. Fair scheduling laws are one example of a concrete policy that would allow workers to more effectively balance work and family.

1. America Needs—and Deserves—a Raise

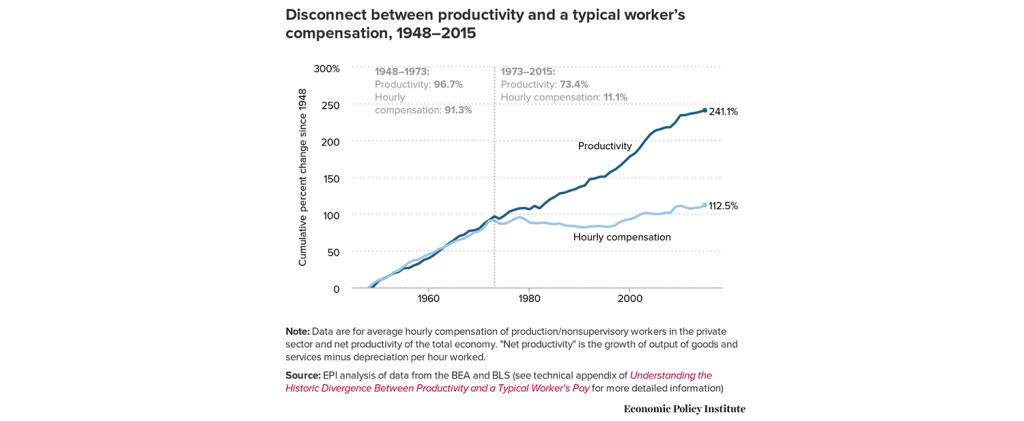

The topic of today’s hearing could not be more timely. Americans need—and deserve—a raise. Over the past four decades, workers have increased their productivity by 73.4 percent.1 During that same time, hourly compensation of working families has only increased by 11.1 percent.2 The average worker makes only $17.86 per hour, which, controlling for inflation, is only modestly better than his counterpart’s pay four decades ago, despite decades of economic growth and tremendous advances in the use of technology in the workplace.3 Furthermore, it is corporations, not working families, who have enjoyed the fruits of the recent economic recovery. For example, from 2000 to 2015, the share of corporate income going to wages sharply declined, from 82.3 percent to 75.5 percent.4 The result has been tremendous gains for the top 1 percent of Americans at the expense of middle and low-wage earners. This is a continuation of a long-term trend: from 1980 to 2014, the pre-tax income of the bottom 50 percent of working-age adults actually declined, while the top 1 percent alone captured 36 percent of all income growth.5

The Changing Economy is Pressing Down Wages

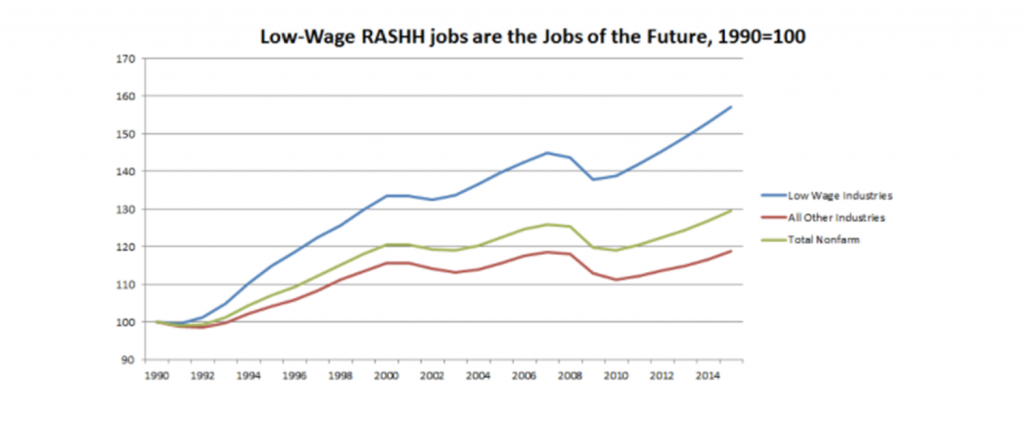

There are numerous factors to blame for America’s stagnating wages. For example, the share of Americans employed in well-paid manufacturing jobs has declined from 22 percent of all jobs in 1976 to 8.5 percent in 2016.6 In manufacturing’s place, the American economy has been characterized by fast growing RASHH (Retail, Administrative and Waste Services, Social Assistance, Hospitality, and Low-wage Health Care) industries that pay under $15 per hour and offer less than thirty hours per week. At the same time, the sharp decline in unionization of the private-sector workforce has contributed to the hollowing-out of middle class jobs.7 Technological change has curtailed the employment prospects of the majority of American workers who have less than a college degree, and the growth of artificial intelligence technologies is bringing new threats to mainstays of the middle-class, such as trucking.8

Inflation and Lack of Congressional Action Have Kept Wages Back

The erosion of the core standards of the Fair Labor Standards Act has facilitated the growth of low-wage jobs and the erosion of the middle class. Congress last voted to increase the minimum wage a decade ago, with the full increase from $5.15 to $7.25 going into effect in 2009.9 At its peak in 1968, the minimum wage represented 54 percent of the average wage of non-supervisory workers, while today it is just a third.10 If the minimum wage had kept up with the rise in prices that wage earners face, it would stand at $10.53—meaning that the minimum wage has lost nearly 45 percent of its purchasing power since its peak level.11 More seriously, the minimum wage for tipped workers is just $2.13 per hour, and has not been raised since 1991.12

A similar pattern of neglect has weakened the Fair Labor Standards Act guarantee of time-and-a-half pay for work beyond forty hours per week. The salary threshold determines which workers are guaranteed overtime pay, and cannot be exempted as executive, administrative, or professional employees. The threshold was set at $250 per week from 1975, until it was raised by the Bush Administration in 2004 to $455 per week. Still, the number of workers protected by the salary threshold has declined from 12.6 million workers in 1979 to 3.5 million in 2014—impacting middle-class workers who have been particularly hard hit by paycheck stagnation.13

The Fissured Economy

These wage trends have been worsened by economic trends that have led to more insecure work, including the fissuring of the workplace, employee misclassification, the growth of the gig economy, and erratic scheduling. The twentieth-century economy was dominated by large firms who used a traditional employment relationship to control every aspect of production. The twenty-first-century management model only entails the firm retaining only the most central aspect of its identity, and outsourcing all other functions. Mechanisms for firms to contract out their workforce needs are becoming increasingly complex, to the point that an average hotel now consists of employees of different contractors responsible for seemingly core functions, such as front desk staff and maid service.14

These fissured arrangements have allowed firms to absolve themselves from employment law responsibilities, leaving workers vulnerable to exploitation, whether they are classified as independent contractors or as employees of contracting agencies. And these arrangements are on the rise. Business spending on outsourced services (defined as all services purchased by businesses except for telecommunications and finances) has risen from 7 percent of GDP in 1982 to 12 percent in 2006.15

Part of this surge in contracting out is the rise of a “1099 economy” of workers paid as independent contractors—often when they should be paid as and afforded the rights of employees. The Department of Labor (DOL) has found that between 10 percent and 30 percent of employers (depending on the state) misclassify part of their workforce as independent contractors, depriving them of basic employment rights. State studies have found as much as 60 percent of audited employees are misclassified.16 Misclassification impacts workers at every wage level in many different sectors, including construction, real estate, home care, trucking, and janitorial workers. Low-wage workers frequently accept pay as independent contractors (or get paid in cash) because that is the only way they can get work, not because they are genuinely in business for themselves.

The rise of the on-demand—or “gig”—economy has generated tremendous attention, (which today accounts for only 0.5 percent of the workforce), most popularly represented by services such as Uber and Lyft.17 While some of these firms effectively use new technology to dispatch drivers, there is nothing new about the concept of labor intermediaries that dispatch workers—and nothing that says those in the gig economy must get 1099s. Gig economy start-ups such as Managed by Q and Shyp actually classify their workforce as employees, rather than independent contractors, so they can provide “additional supervision, coaching, branded assets and training” to “ensure that each time a customer uses Shyp they have an incredible experience.”18 The innovation of the gig economy should be to facilitate the delivery of services, but all too often it has been used mostly to facilitate the expansion of platforms whose profits depend on avoiding playing by the rules facing more traditional employers.

The Changing Economy has Led to Rampant Violations of Wage and Hour Law

The fissuring of employment, the rise of misclassification, and scheduling abuses are just some of the factors that have led to a dramatic rise in wage and hour violations. A scientific sample conducted by researchers in three major cities found that 26 percent of all low-wage workers had minimum wage rights violated, and 76 percent of those who worked more than forty hours had their rights violated.19 Surveys of fast food enterprises have found that 90 percent of workers report at least one violation.20 Not surprisingly as violations have increased, so has FLSA litigation, with the Government Accountability Office reporting a 514 percent increase in the number of federal wage and hour cases filed from 1991 to 2012. 21

2. The Need to Modernize Fair Labor Standards Act Regulations

The economic headwinds facing workers and their families require reforms that both strengthen core elements of the law, bolster enforcement, and modernize the Department of Labor to new challenges caused by the fissuring of employment.

In this context, the nomination of Mr. Andrew Puzder for Secretary of Labor raises concerns about the future ability of the Department of Labor to implement much-needed wage and hour policies, and to pursue the types of strategic enforcement necessary to ensure that American workers will share in the prosperity that their labor generates. President Trump has chosen as chief enforcer of our nation’s employment laws someone from the ranks of an industry with one of highest rates of wage and hour violations, and someone who has pursued a business model often predicated on strict control of labor costs and cutting corners on employment laws. The Century Foundation’s research uncovered 1,082 substantiated violations of wage and hour laws since Mr. Puzder took control of Hardee’s and Carl’s Jr. restaurants (owned, operated and franchised by CKE Restaurants) in 2000, with workers refunded nearly $150,000 of back wages in those cases.22 From the start of the Obama administration, 60 percent of the CKE restaurants investigated had at least one violation—and the documented violations likely represent only a small share of the wage and hour infractions at CKE restaurants that Mr. Puzder would now be charged with rooting out. Indeed, there have been additional complaints by CKE Restaurants’ workers about working off the clock, debit card fees that cheated workers out of a minimum wage, and failing to pay overtime for on-call hours worked by general managers.

Beyond his record, Mr. Puzder is a prolific public speaker and writer who has decried the overall impact of regulations on the economy as negative, and who spoke out against recent efforts to strengthen labor and employment laws. Every past Republican nominee for Secretary of Labor has pledged to Congress that they would uphold the unique mission of the Department of Labor to enforce the Fair Labor Standards Act, as well as the 180 other laws entrusted to the department’s staff. Past nominees include Ray Donovan, a construction executive and President Reagan’s first Labor Secretary, who said “Any good manager, regardless of the law, has to concern himself with safety.” For his part, Mr. Puzder has openly questioned the need for a federal minimum wage and the need to update overtime standards, and said specifically that he prefered robots over workers because “they’re always polite, they always upsell, they never take a vacation, they never show up late, there’s never a slip-and-fall, or an age, sex, or race discrimination case.” His overall view is that “more government is not the solution to every problem, it’s the problem to every solution.”23 It is unclear whether Puzder can bring the kind of balanced view required to lead an agency of committed civil servants dedicated to upholding employment laws.

The First Priority Is to Advance a Substantial Increase to the Minimum Wage

Changes in the economy, along with the decline in unionization and lagging bargaining power of low-wage workers, have made minimum wages a more important policy lever than ever before. A national wage of $12 per hour, phased in by 2020, would provide raises (averaging $2,300 per year) for 35 million workers. This type of minimum wage increase, or proposals to phase in a $15 wage several years later, would account for the gains in worker productivity, restore the power of the minimum wage to reduce inequality, and reinvigorate the economy at the lower-end of the wage scale.24 As part of these proposals the subminimum tipped wage should be eliminated (as done in 8 states), which will have the added benefit of eliminating costly litigation over the tip credit.

Despite stereotypes of minimum wage workers as young people starting in the labor force, two-thirds of those who would benefit from the increase are over the age of 25 and, on average, are the primary breadwinners in their families.25 Thirty-five percent of African-American workers would benefit, as would 38 percent of Hispanic workers, and 21 percent of white workers.26

Economic research has increasingly found that minimum-wage increases have little negative impact on employment, even among teenagers identified as most vulnerable in previous research and critics of increases.27 Minimum-wage increases save companies money through reductions in labor turnover and improvements in organizational efficiency, as documented in successful retailers who pay high wages and enjoy high productivity and high profits like Costco, QuikTrip, and Trader Joe’s.28 Detailed economic analysis of $15 minimum wages (already enacted in New York, California, and in cities in four other states) found that they could actually lead to a net gain in jobs as a result of increased productivity and greater spending power by low-wage workers.29

Sustain the Recent Modernization of Overtime Rules

The recent regulation promulgated to modernize overtime rules is both prudent and highly impactful. The new level of $921 per week was conservatively set, so that the bottom 40 percent of workers in the poorest parts of the nation would be guaranteed overtime pay. The increase would expand overtime rights for 4.2 million workers, and clarify them for an additional 8.9 million. 30 Before the federal court in the Northern District of Texas enjoined the rule, a diverse set of companies, including Walmart, had already begun to raise employers salaries to conform with the new rules—part of the $1.2 billion raise estimated to be triggered. It is hard to imagine another policy that could have as much of an impact for middle wage workers (earning $10 to $23 per hour). While there were grave concerns about the impact of the rule on certain sectors, like Higher Education, these have often overblown. In the case of higher education, many academic and administrative staff qualify for special exemptions, and only a small portion would be impacted.31 Increases in tuition won’t be necessary. For example, the National Institutes of Health agreed to raise its grant levels so postdoctoral fellows could be paid above the new threshold without additional cost to the institution.

The overtime rule has the added benefit of simplifying compliance. The increase in the salary test tells employers clearly which modest and low-pay salaried workers are guaranteed overtime—and would substantially reduce the number of workers who would need to be subjected to the more complicated duties test. The Bush Administration defended a proportionally larger increase in the salary test from $155 to week to $455 in 2004, with similar logic.

Support Strategic Enforcement

The Department of Labor has limited resources, as the number of investigators actually declined by 14 percent from 1975 to 2004, even as the number of covered workplaces increased by 112 percent.32 The Department of Labor now has about 1,000 investigators to handle 7.3 million establishments. Targeted enforcement policies, focusing on industries where research has surfaced high levels of violations, is the only way for Department of Labor to utilize its resources to recover significant amounts of unpaid wages and to move industry practices. For example, a directed investigation of a fast food restaurant was found to decrease violations at other fast food restaurants in the same zip code by 33 percent.33

With the probability of a Department of Labor investigator engaging an individual employer so low, it is critical for the Department to be able to wield all of the tools in its arsenal (such as liquidated damages, litigations, hot goods, civil penalties) to deter other employers from stealing worker’s pay. Partnerships with community based organizations can help to identify violations and raise standards within industries with chronically high violations. The model of the Susan Harwood Grants to community groups around OSHA could be applied to expand the reach of Wage and Hour as well.

The Department of Labor has moved to a targeted enforcement strategy while maintaining the effectiveness of its investigations—remarkably achieving nearly the same percentage of investigations that find violations in its directed investigations (79 percent) than in ones where a worker actively lodges a complaint (82 percent).34 And because these investigations are in targeted sectors, they are more effective—the average amount recovered per investigation increased from $785 per worker in FY 2009 to $1,000 per worker in FY 2015.35 These efforts have led to $1.6 billion in back wages for more than 1.7 million workers in over 209,000 investigations.

Recent Guidance Has Clarified Rules for Employers and Employees

Strategic enforcement can be greatly assisted by guidance from the Department of Labor that becomes visible to employers, worker advocates, and employers. The rise in subcontracting, use of third-party administrators, franchising, and staffing firms have made it confusing about who is ultimately responsible for meeting wage and hour responsibilities. The Administrative Interpretation issued in 2016 clarifies existing policies and case law in which firms would be found to have a joint employment responsibility. The goal of such guidance is to ensure that entities that exert control over the working conditions of their subcontractors will be held liable for wage violations. There is much that franchisers can do to protect themselves and their subcontractors from wage violations. For example, the Department of Labor and Subway agreed to a voluntary program of compliance education and software-based flagging of possible violations.36

The Administrator’s Interpretation issued by the Department of Labor in 2015 on independent contractor misclassification has a similar educational goal in mind. It reiterated that FLSA uses a broad standard of whether an employer “suffers or permits” an individual to work for them, and that the courts have used a multi-factor economic realities test to determine whether an individual is in fact economically dependent on the employer. The goal of this Administrator’s Interpretation is to encourage employers to only treat individuals as independent contractors if they are truly in business for themselves. Too often, workers are misclassified as independent contractors based on one element (such as owning their own tools) when they are in fact in an employment relationship. The Administrator’s Interpretation was put in place to give employers numerous examples of such cases to avoid.

Responding to the Desire of Workers for Flexibility

A common point of debate is whether the Fair Labor Standards Act inhibits the flexibility of workers and employers. Nothing in the FLSA prevents any of the common examples of flexible work (working from home, working split shifts, doing piece work, or other forms of intermittent work) as long as these arrangements ensure that the worker is paid for their work, at least at the minimum wage, and with overtime pay for any hours over forty hours per week.37 Technology should make it easier than ever to track work hours using a myriad of available smart phone applications. The Department of Labor should clarify how the Fair Labor Standards Act applies to the use of smartphones and other forms of flexible work, and offer compliance assistance to employers.

In fact, workers today actually are craving stability in their schedule. A unique study found that hourly workers would actually take a 20 percent pay cut if they were guaranteed a set, 9-to-5 schedule; furthermore it found that a set schedule was worth more economically to hourly workers than added flexibility to work from home.38 Modifications to wage and hour policies would make life easier on hourly workers by providing, say, two weeks of advance notice of a worker’s schedule, and offering a modest economic disincentive to changes in worker’s schedules: one hour of premium pay to workers whose schedule is changed writhing twenty-four-hours notice, and one hour of reporting pay to workers who are sent home early for a shift.

Additionally, workers need the ability to take paid time for the birth or adoption of a child, or when they or a family member are seriously ill. Compensatory time proposals such as the Workplace Flexibility Act fail that test. Under that proposal, employers would have the right to refuse a request for time off if it conflicts with business interests. Nothing in current law prevents employers from paying workers time-and-a-half for overtime and then giving them time off the next week as a reward for working extra hours, and thus comp time proposals represent a needless intervention by Congress.

Conclusion

In summary, in order for tens of millions of additional workers across the country to share in the nation’s economic prosperity, they need a boost in the minimum wage and overtime laws, a long-term commitment to strong enforcement of the wage and hour laws,new resources to root out misclassification that regularly cheats them out of wages, and a strong effort to apply the Fair Labor Standards Act to workers in the gig economy and other forms of twenty-first–century work.

Notes

- Economic Policy Institute, “The Productivity-Pay Gap,” August 2016, http://www.epi.org/productivity-pay- gap/.

- Ibid.

- Heidi Shierholz, “Remaining Challenges: Why So Many People Feel Forgotten in This Recovery,” Economic Policy Institute, February 9, 2017, go.epi.org/perkinspreview.

- Josh Bivens, “The Decline In Labor’s Share of Corporate Income Since 2000 Means $535 Billion Less for Workers,” Economic Policy Institute, September 10, 2015, http://www.epi.org/publication/the-decline-in-labors-share-of-corporate-income-since-2000-means-535-billion-less-for-workers/.

- Thomas Piketty, Emmanuel Saez, and Gabriel Zucman, “Economic Growth in the United States: A Tale of Two Countries,” Washington Center for Equitable Growth, December 6, 2016, http://equitablegrowth.org/research-analysis/economic-growth-in-the-united-states-a-tale-of-two-countries/.

- J. Bradford DeLong, “NAFTA and Other Trade Deals Have Not Gutted American Manufacturing—Period,” Vox, January 24, 2017, http://www.vox.com/the-big-idea/2017/1/24/14363148/trade-deals-nafta-wto-china-job-loss-trump;

- Richard Freeman, Eunice Han, Brendan Duke, and David Madland, “What Do Unions Do for the Middle Class?” Center for American Progress, January 13, 2016, https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/economy/reports/2016/01/13/128366/what-do-unions-do-for-the-middle-class/.

- Council on Economic Advisers, “Artificial Intelligence, Automation, And The Economy,” Whitehouse.gov, December 20, 2016, https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/whitehouse.gov/files/images/EMBARGOED%20AI%20Economy%20Report.pdf.

- U.S. Department of Labor, History of Federal Minimum Wage Rates Under the Fair Labor Standards Act, 1938 – 2009, https://www.dol.gov/whd/minwage/chart.htm.

- Craig Ewell, “Inflation and the Real Minimum Wage: A Fact Sheet,” Congressional Research Services, January 8, 2014, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R42973.pdf.

- Author’s calculation using the CPI-W series, available at https://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/surveymost?cw.

- Sylvia Allegretto and David Cooper, “Twenty-Three Years and Still Waiting for Change,” Economic Policy Institute, July 2014, http://www.epi.org/publication/waiting-for-change-tipped-minimum-wage/.

- Ross Eisenbrey, “Testimony Before the U.S. Senate Committee on Small Business and Entrepreneurship” May 11, 2016 http://www.epi.org/publication/testimony-raising-the-overtime-threshold-is-an-important-improvement-in-working-families-labor-standards/.

- David Weill, The Fissured Workplace, (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014.

- Yuskavage, Robert E., Erich H. Strassner, and Gabriel W. Medeiros, “Outsourcing and Imported Services in BEA’s Industry Accounts,” International Flows of Invisibles: Trade in Services and Intangibles in the Era of Globalization, eds. Marshall Reinsdorf and Matthew Slaughter (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008), 247–288.

- National Employment Law Project, Independent Contractor Misclassification Imposes Huge Costs on Workers and Federal and State Treasuries, July 2015.

- Lawrence Katz and Alan Krueger, The Rise and Nature of Alternative Work Arrangements in the United States, 1995-2015, Harvard University http://scholar.harvard.edu/files/lkatz/files/katz_krueger_cws_v3.pdf?m=1459369766.

- Kevin Gibbon, “A Note from Shyp’s CEO,” July 1 2015, http://blog.shyp.com/shyp-ceo-note/.

- Annette Bernhardt et al. “Broken Laws, Unprotected Workers,” Center for Urban Economic Development, National Employment Law Project, UCLA Institute for Research on Labor and Employment, 2009 http://web.archive.org/web/20141102153212/http://www.nelp.org/page/-/brokenlaws/BrokenLawsReport2009.pdf?nocdn=1.

- Tiffany Hsu, “Nearly 90% of fast-food workers allege wage theft, survey finds,” April 1, 2014 http://articles.latimes.com/2014/apr/01/business/la-fi-mo-wage-theft-survey-fast-food-20140331 .

- Government Accountability Office, The Department of Labor Should Adopt a More Systematic Approach to Developing Its Guidance, “http://gao.gov/products/GAO-14-69.

- Michael McCormick and Simon Glenn-Gregg, “Mapping Andy Puzder’s Labor Violations,” The Century Foundation, January 12, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/facts/mapping-andy-puzders-labor-violations/.

- Andrew Stettner, “GOP Secretaries of Labor: Puzder Is a Break from the Past,” The Century Foundation, January 23, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/report/gop-secretaries-labor-puzder-break-past/.

- David Cooper, “Raising the Minimum Wage to $12 by 2020 Would Lift Wages for 35 Million American Workers,” Economic Policy Institute, July 2015, http://www.epi.org/publication/raising-the-minimum-wage-to-12-by-2020-would-lift-wages-for-35-million-american-workers/.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- John Schmitt, “Why Does the Minimum Wage Have No Discernible Effect on Employment,” Center for Economic Policy Research, February 2013, http://cepr.net/documents/publications/min-wage-2013-02.pdf.

- Zeynep Ton, The Good Jobs Strategy, (New York: New Harvest Books, 2014).

- Michael Reich, Sylvia Allegretto, Ken Jacobs, and Claire Montialoux, “The Effects of a $15 Minimum Wage in New York State,” Center on Wage and Employment Dynamics, March 2016, http://irle.berkeley.edu/files/2016/The-Effects-of-a-15-Minimum-Wage-in-New-York-State.pdf.

- U.S. Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Division, Overtime Final Rule, Summary of the Economic Impact Study, 2017, https://www.dol.gov/whd/overtime/final2016/overtimeFinalRule.pdf.

- U.S. Department of Labor, Overtime Final Rule and Higher Education, 2016 https://www.dol.gov/sites/default/files/overtime-highereducation.pdf

- Annette Bernhardt and Siobhán McGrath, “Trends in Wage and Hour Enforcement by the U.S. Department of Labor, 1975–2004,” Brennan Center for Justice at NYU School of Law, September 2005, http://www.nelp.org/content/uploads/2015/03/Trends-in-Wage-and-Hour-Enforcement.pdf.

- David Weil, “Improving Workplace Conditions through Strategic Enforcement,” U.S. Department of Labor Wage and Hour Division, May 2010, https://www.dol.gov/whd/resources/strategicEnforcement.pdf.

- Ibid.

- U.S. Department of Labor Wage and Hour Division, “Transition Documents,” November 2016, https://www.dol.gov/dol/foia/presidential-transition-docs/whd.pdf.

- Ben Penn, “Subway, DOL Compliance Deal a New Template for Franchises?” Daily Labor Report, August 2, 2016 , https://www.bna.com/subway-dol-compliance-n73014445701/.

- David Weil, “Flexibility and Fair Pay: You Can Have Them Both,” U.S. Department of Labor, February 18, 2016, https://web.archive.org/web/20160425095705/http:/blog.dol.gov/2016/02/18/flexibility-and-fair-pay-you-can-have-both/.

- Alexandre Mas and Amanda Pallais, “Valuing Alternative Work Arrangements,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper #22708, September 2016, http://www.nber.org/papers/w22708.