Investing in student leadership is essential. Students are the first and most courageous actors in major social movements, and have been on the forefront of change from the fights against Scott Walker in Wisconsin to the fossil fuel divestment movement. Student organizing, as well as the skills and networks that students build while organizing on campus, provide a testing and breeding ground for the leadership of the progressive movement. Moreover, student loans, disproportionately burdening low-income students and students of color, are a major barrier for an entire generation of diverse youth leaders who would otherwise work for progressive organizations.

Despite such barriers, student training and organizing programs are underfunded and often first to be cut when foundation endowments drop during economic downturns. Even in the best of times, analysis shows that progressive youth organizations still have 60 percent fewer staff than right-wing student organizations.

The answer to funding the gap in leadership development must be more comprehensive than asking the same big donors to donate more from the same advocacy budgets. While this approach has led to an increase in youth funding over the past fifteen years, this strategy has not achieved the scale required to turn the tide on crucial issues.

Part of the solution must be that youth organizations pursue proven, scalable small and middle donor programs, as their counterparts on the right have mastered.1 Part of it may be member benefits or other forms of scalable revenue. But the most successful businesses have demonstrated that competing in existing, known spaces for revenue is not enough to drive continuous growth over time. Instead, what is required is a blue ocean strategy.

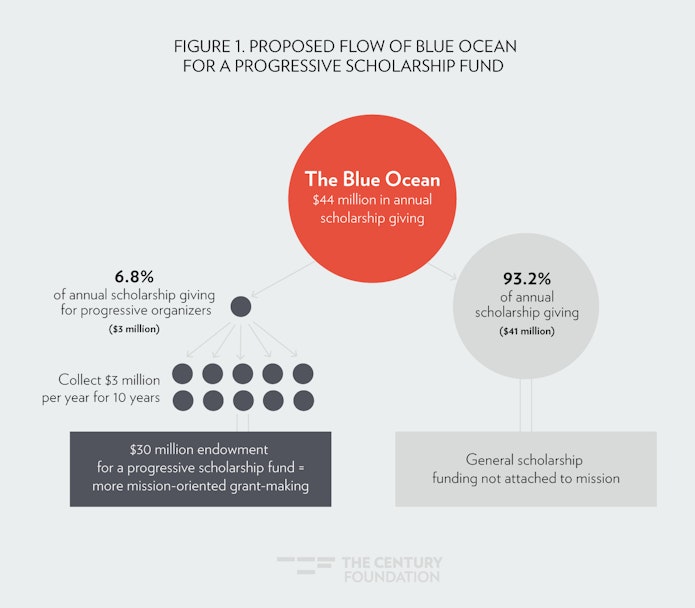

Over one hundred U.S. foundations that give generously to progressive causes have the opportunity to focus the $44 million that they give in college scholarships each year on student leaders who are the next generation of champions of the very progressive causes that these foundations fund. This amount is greater than or equal to the total annual funding for progressive youth community organizing in five of the eight years between 2006 and 2013. If $3 million (about 7 percent) of this scholarship funding was given directly to emerging progressive youth leaders, progressive foundations could use their existing scholarship funds to create an unmatched funding stream to build a diverse pipeline of progressive leaders (see Figure 1). Such a program could help reopen the pipeline to nonprofit progressive jobs for economically and racially diverse students, provide needed funding for leadership development, and build a vast network of progressive students running and winning campaigns.

This report presents new research on a subset of foundations that already both give to social justice causes and separately give to scholarships. We surveyed a universe of 687 prospective progressive foundations compiled via the Foundation Center, and found 120 mission-driven foundations that both meet the criteria of a social justice mission and also have a consistent scholarship giving function. Using the Foundation Directory Online database we analyzed their tax documentation (Form 990s), annual financial reports, and websites to estimate annual scholarship giving. An online survey was distributed and surveys by phone were conducted for some foundations with no specific scholarship amount on the Foundation Center website.

The 120 foundations were selected based on stated commitments to social justice, economic justice, the environment, and human rights, according to the Foundation Directory Online database. Individual donors, foundations with more than $10 million in annual scholarship giving, and general education funds were excluded from the analysis. Community foundations were also largely excluded, unless funds were explicitly given to progressive oriented scholarships. Annual scholarship amounts were determined from the most recent financial documents available for each foundation, from fiscal years 2012–2015. Considering that $3.1 billion was allocated to social justice grantmaking in 20112 by one thousand large foundations, a smaller per annum allocation of general scholarship funds to a progressive scholarship fund is a cost-effective way for foundations to leverage their missions.

Our research found a major opportunity. Social justice foundations are giving $44 million to scholarships, but this giving is not directly advancing the grant making mission of the foundations. If the foundations were to direct a portion of those scholarships to strategic talent development, they would amplify their programmatic grants. Figure 1 illustrates how a $3 million per year commitment to this project could create a $30 million endowment for organizing scholarships that would create a pipeline of social change organizers.

Structured correctly, a progressive scholarship program could be created that would cost-effectively recruit and pay for the college tuition for the best rising civic leaders entering college, cover their living expenses, provide paid internships and fellowships to build skills and valuable career networks, and offer advocacy training and paid work study to enable students to work on actual campaigns with local and national organizations.

Pooling funds into one cross-foundation scholarship program could reduce the overhead spent by foundations on the selection of scholarship recipients by streamlining recruitment using local volunteers and predictive analytics, amplify foundation funds by supporting efforts to raise small donor income for additional scholarships, and multiply the impact of foundation giving by enlisting scholarship recipients in campaigns aligned with the missions of the foundations.

The “Blue Ocean” strategy,3 developed by professors Renee Mauborgne and W. Chan Kim, emphasizes a need for organizations to innovate the goods and services they offer in order to create new markets for their products. In this case, student activism, leadership development, and impact through activism have been the product or service pitched to foundations and major donors. Unfortunately, there are far more student and youth organizations on the left, with far less money going into them, than on the right.

This report, which is the second in a series that The Century Foundation4 is issuing about how to solve the business model problem for organizing, we look at an entirely different funding space for student activism—scholarships—through which progressive foundations and donors give far more money each year. We posit that by combining student activist development with scholarships, work study, and paid internships, a new offering can be provided to donors—allowing foundations to continue to fund scholarships while more closely aligning those scholarship programs with their progressive agendas.

The Opportunity

Foundations: Leveraging Resources to Meet Their Missions

With scholarship programs for progressive organizers, foundations have the opportunity to leverage their assets more efficiently to meet their missions. Those foundations that already give generously to progressive causes have another opportunity to bolster the progressive movement via scholarship programs that develop the next generation of movement leaders. Our analysis suggests that about $44 million per year that foundations give in college scholarships could be routed to scholarships for progressive organizers at the college level.

The scholarship model itself provides benefits to progressive foundations already contributing to scholarship funds. By redirecting a portion of their scholarship funding to a progressive scholarship fund, they are cost-effectively contributing to a fund that can advance their mission while providing scholarship money to those students who need it most. It is also an entirely new stream of funding that would involve less competition with other foundations looking to make an impact (Kim and Mauborgne’s Blue Ocean strategy). This novel use of foundation funding could also encourage further small donor donations to participating foundations, increasing their operating income.

If 10 percent of the 44 million was rerouted to progressive youth leaders, foundations could direct a portion of the money they already spend on college scholarships to advance their own progressive missions more effectively. Foundations could contribute funds initially and then evaluate the impact of their contributions by gauging the development of students as leaders and the progress of campaigns. Since leadership development movement-building takes time, foundations could evaluate the success of the program after three years. If satisfied with their impact, they could then contribute to the scholarship fund endowment on a more permanent basis.

As explained below, working class students and students of color face significant barriers to finding jobs in the public interest, as mounting student debt and decreased opportunities for organizing deter students from seeking careers in nonprofit organizing. Many colleges and universities are already a hotbed for progressive organizing. Therefore, scholarships to college students with the explicit intention of supporting organizers on the left are a very safe investment. The challenge is to leverage the hotbeds that already exist to bolster social movements beyond the university level, or to expand to other universities with less of an affinity for organizing.

Such an expansion offers foundations with progressive focuses a unique opportunity to advance their missions. Many advantages exist to reopening such a pipeline, including developing leaders for careers in the progressive movement in the future (perhaps even within the very foundations supporting the fund), bolstering social movements in the present with experienced student organizers, and creating a diverse group of students who will bring creativity and expertise to existing campaigns.

The pooling of funds into one cross-foundation scholarship fund would help to improve cost-effectiveness while reducing overhead attributable to recruiting scholarship recipients. Local volunteers and organizations in partnership with the scholarship fund could handle recruitment and the enlistment of scholarship recipients into local, regional, and national campaigns in line with the missions of the foundations that fund the scholarships. Foundations would simply need to contribute funds to the scholarship programs in partnership with the ground work (such as training, programming, and leadership development) that would be handled by local and national organizations.

Environmental justice, labor and alt-labor, and racial justice organizers could all benefit from support from a singular fund that facilitates an intersectional approach to progressive organizing.

The benefit of one large scholarship fund for progressive organizers at the college level also brings the potential for communication and collaboration between social movements; environmental justice, labor and alt-labor, and racial justice organizers could all benefit from support from a singular fund that facilitates an intersectional approach to progressive organizing.5 Combine this with an explicit focus on promoting diversity in organizing, and the potential for creating a cross-sectional progressive movement in the United States (via a pooled scholarship fund) becomes an achievable goal for foundations in the medium-to-long term.

Ultimately, a scholarship fund built on this model serves two concrete purposes for participating foundations, one mission-oriented and the other monetary-based. Firstly, it allows foundations to allocate money in a unique way to meet their missions. Secondly, it is a novel use of funding that would encourage small donor contributions from those interested in funding these scholarship programs, thereby increasing the revenues of foundations.

Guidelines for Programs Funded by the Progressive Scholarship Fund

A concrete blueprint for the program would need to be tested with a pilot program, with significant input and participation from all stakeholders involved. However, some general principles—such as a focus on leadership development, skills acquisition, networking and involvement in campaigns—can serve as an overarching blueprint that can be taken up by foundations, organizers and students involved in the scholarship fund.

With a pooled scholarship fund directed by progressive foundations, various programs could be supported for students to develop as progressive civic leaders. The general structure would include programs that recruit and pay for the college tuition of the best rising civic leaders in high school, entering college or displaying potential in college (since much politicization and involvement begins in college), cover living expenses, provide paid internships and assistantships to build networks and skills, and provide work-study assistance for students to gain experience in real local and national campaigns. An application process could assist in placing students with scholarships in activist circles that align with their interests, or have the potential to develop their organizing skills.

A program supported by the fund could be geared toward various progressive social movements, but could also include a holistic approach to organizing that counters the “siloing” of movements, which often undermines the power of progressive movements in aggregate. This is especially important in the current political climate.6 Programs could continue to have specific movement focuses led by local and national organizations currently organizing in progressive spaces, but the pooled fund could also facilitate communication between different programs to develop new strategies, tactics, and best practices.

Leadership development, whereby students in the scholarship programs are trained to perform leadership roles in organizations and activist movements, is the primary goal of the scholarship program. Recruiting and training the progressive movement’s next generation of civic leaders would begin in earnest via targeted leadership development and direct involvement in campaigns.

Leadership development in programs funded by the scholarships would need to follow general principles that are conducive to developing the next generation of progressive civic leaders. Research of Sierra Club chapters’ internal leadership development structure by Marshall Ganz and others shows that organizations with committed activists who consistently build organizational capacity (leadership development, recruitment) generate “increased organizational effectiveness across outcomes.”7

Several broad principles can be gleaned from this research. For one is learning-by-doing, which is an essential piece of the proposed program. Enhancing the skills of students funded by the scholarships simultaneously develops their leadership skills while building the organizational capacity of the groups they work with in work-studies or internships. Developing skills in recruitment, building, and leading organizing campaigns, public policy analysis, and power analysis are all essential to the success of students who would be in the program.

Training sessions can instruct students in the basics of organizing; the inclusion of such sessions would enable them to apply their skills concretely through the organizations they are partnered with via organizing campaigns. Theory and practice will be equally emphasized in the program, with the connection between the two informed by concrete experiences in activism. Autonomy of local movements and organizations will be respected here, as they can broadly agree to the principles outlined in the scholarship fund, but take on the responsibility of training and developing student-organizers.

Mentorship and networking can maximize the effectiveness of leadership development. Experienced organizers in participating activist organizations can mentor students while connecting them with movements on the national level. They can also have the foresight to place student-organizers into public interest nonprofits after their graduation, re-opening the progressive pipeline.8

Such an approach to leadership development that rests on local organizations involved with the scholarship fund will serve multiple purposes. These organizations would be able to build their organizational capacity, bolstering their ability to build and win campaigns. The organic and action-oriented training of students would also allow them to apply skills gained in more classroom-oriented training sessions.

Students are often the vanguard of many social movements. As such, it is imperative programs funded by the scholarship fund focus on the development of these young leaders and their immersion into the activist organizations in which they are placed. Marshall Ganz describes community organizing as the development of “leaders that can mobilize people to confront and build political power.”9 Students have been a part of this dynamic for decades.

Students: Movement Leaders

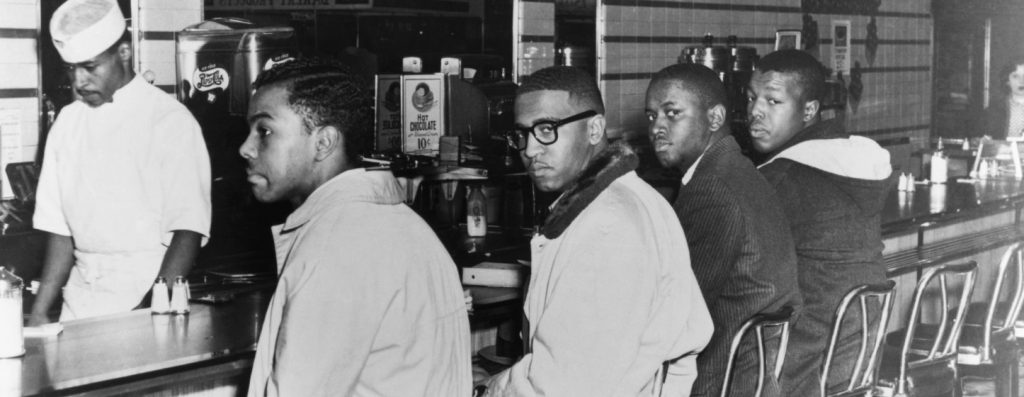

Students are often the first to act, and most likely to courageously lead, in social movements. Indeed, most of the major movements of the 1960s and early 1970s in the United States—civil rights, welfare rights, and the anti-war movements—were predominantly born out of student organizations.10 From the movement in Wisconsin against Scott Walker11 to the leadership of high school DREAMers12 to the civil rights13 and climate movements,14 students have played key roles. While they have often had financial support and mentorship from trained staff at major organizations, students have often acted first and with the greatest courage to transform our society.

The lunch counter sit-ins were started on February 1, 1960 by four African-American students who sat down at Woolworth’s lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina to order a cup of coffee. The result of their courage—and that of the hundreds of students who mobilized in the subsequent days—resulted in Woolworth’s counters being desegregated. The victory inspired kneel-ins at churches, read-ins at libraries, wade-ins at public pools and beaches, and walk-ins in theaters. Students led, stood, and sat in on the front lines of the efforts to accelerate desegregation.15

Claudette Colvin was a fifteen-year-old when she refused to give up her seat on a Montgomery Bus, nine months before Rosa Parks. She was one of the four defendants in the case that went to the Supreme Court that struck down segregation.16,17

John Lewis, a seminary student, was one of the first thirteen freedom riders. When the freedom riders buses were burned, the Congress on Racial Equality, at that point led by adults, called it quits, Diane Nash, who founded the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), organized a group of ten students to risk their lives and continue the rides, forcing the Kennedy Administration to intervene in favor of desegregation.18

Students made apartheid an issue in the public’s mind when, in 1984, they convinced fifty-three colleges and universities to divest from companies doing business in South Africa. By 1987, that number grew to 128, and by 1988 the number had reached 155 colleges and universities.19 Cities and states followed suit, and finally Congress moved to tax companies supporting the apartheid regime.20

In 2000, the Global Climate Coalition (GCC), the leading industry coalition spreading misinformation about global warming science, largely collapsed after losing almost all of its corporate members. Pulitzer Prize winning author Ross Gelbspan wrote: “The defeat of the Global Climate Coalition reflects, among other things, a student divestiture campaign which urged universities to divest their holdings in companies that belonged to the GCC.”21

Racial justice organizing has drawn strength from the dynamism of student organizers in college. From Black Lives Matter22 to the direct action tactics at Mizzou,23 students’ creativity has been essential to challenging individual and structural racism on campus and throughout the United States. What is more, these movements have set a great example for activists on the left looking to develop a comprehensive political platform.24

Recently, the labor movement has also been emboldened by the actions of students, both as community members standing in solidarity with workers and as workers themselves. National organizations like United Students Against Sweatshops (USAS)25 and the Student Labor Action Project (SLAP)26 are initiatives designed to engage students in the labor movement with chapters on the college level.

Successful campaigns have included supporting Resident Assistants contract negotiations, unionizing Peer Mentors27 at the University of Massachusetts Amherst,28 and helping dining workers get a fair contract with their employers.29 Another prominent example of this student-labor activism was at Harvard, where students have provided support for and solidarity with striking dining workers;30 a deal was reached after pressure on the university to meet workers’ demands31 Faculty and graduate student unions have also been supported by students. Following the NLRB ruling in late August 2016 that upheld graduate students’ right to unionize at private universities, graduate students are directly involved in unionization efforts with undergraduate students in a supporting role.32 The lockout of faculty at Long Island University-Brooklyn in September 2016 was met with student and faculty protests that eventually led to a re-opening of classes and a contract agreement between the faculty and the university.33 Faculty at fourteen campuses in Pennsylvania struck in October of the same year over contract negotiations, with support from students on the picket line.34

In 2011, the protests against Governor Walker’s attack on the collective bargaining rights of Wisconsin public sector workers was an example of the potential for student involvement in the labor movement. Students from the University of Wisconsin flooded the halls of the Wisconsin Capitol Building, occupying it for two weeks in late February and continuing demonstrations throughout the spring. Student actions on Valentine’s Day included a hundreds-strong march to the Capitol Building to deliver thousands of Valentine’s cards criticizing Governor Walker’s anti-union budget proposal.35 Dynamic and creative direct action led by students galvanized other members of the community, leading up to the occupation of the Capitol Building, where students and members of the community demonstrated with workers and labor groups.36 The sort of community-based unionism on display at the Wisconsin protests demonstrates the strategic importance of group collaboration; student involvement was essential to the demonstrations.37

Students play important roles in these movements, whether as direct organizers or as community members acting in solidarity with other groups. They provide creativity, resources, and a reliable base to many social movements. Students also have broader opportunities for politicization and outlets to act on that politicization, including existing organizations and connections made on college campuses. That is, the college and university environment provides tools for activism and connection that are not always available outside of the purview of higher education. Sociological research suggests that campus-based social networks increase the likelihood of student protests at universities. Recruitment and mobilization is facilitated by the close interaction of students on campuses.38 Indeed, new recruits that go on to become recruiters for student organizing perpetuate the politicization process, making students a reliable bloc for organizing. When these organizations are plugged into broader social movements and community stakeholders, their potential for action increases. Student activism is also more likely to be present on campuses with a culture and history of activism.39 This likely contributed to the outpouring of student support from UW Madison’s student body during the Wisconsin protests.

Movements that engage students early on in social justice organizing and progressive leadership are stronger and can go on to influence those students’ career paths. Students are indispensable parts of many social movements and often become professional organizers in the future when they are engaged. While many consider careers in the public interest and in various community-oriented nonprofits, significant impediments are in place for many students, particularly students of color and working class students. Financial support and funding are essential for social movements and student organizers alike. Developing student organizers to bolster social movements and developing professional organizers are equally valued objectives for the scholarship program we envision.

The Problem

Dearth of Funding for Leadership Development of Student and Youth Advocates

The markets closed on September 11, 2001, and stayed closed until September 17, the longest shutdown since the Great Depression. On the day the market reopened, the Dow Jones dropped 7.1 percent in value, setting the record for the biggest decline in one trading day. By week’s end, the Dow was down by 12 percent, representing a $1.4 trillion loss in capital and investments in just five days. Foundations, corporations, and donors responded to the atrocities of 9/11 and their resultant philanthropic budgets in three ways: generously giving $1.1 billion to support the rebuilding efforts after 9/11, continuing to fund core grantees as much as possible, and pulling back from lower priority grantees.

The lower priority grantees for environmental funders were organizations that provided the essential student volunteers for national environmental campaigns and that served as a crucial training ground for environmental and progressive leaders. Foundation and major donor funding for these groups dropped from about $5 million per year to $1 million per year. The leading networks, Free the Planet! and EnviroCitizen, closed their doors soon thereafter.

The Foundation Center recently added a new code for tracking community organizing grants. Initial data compiled for this paper by the National Council on Responsive Philanthropy demonstrates that youth organizations experienced a similar drastic reduction in foundation funding during the Great Recession, much like they did during the downturn post-9/11.

The fortune of unions similarly impact funding for youth leadership development and organizing programs. Union Summer, the AFL-CIO’s eight-week summer training program for college students, was closed when several unions left the AFL-CIO. The program has been restarted, but declining revenue from the AFL-CIO’s affinity credit card program as well as a flattening of dues has put significant budget pressure on student organizing and leadership development programs such as Union Summer.40

The consequences of these changes could be significant. Budget pressure could potentially cut off a major leadership pipeline in the labor movement. If closed, an entire generation of young organizers could be cut off from involvement in a labor movement that needs broad-based support, now more than ever. Funding that is more reliable and less susceptible to market shocks is necessary to keep these pipelines open, especially when they are developing student organizers by involving them in cutting edge organizing campaigns.

Student Debt Is Blocking the Pipeline for Diverse Leadership

In September 2015, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau stated that “a growing body of evidence suggests that rising levels of student loan indebtedness may also have had spillover effects on other segments of the economy… inhibiting borrowers from pursuing careers as healthcare providers and educators in underserved communities, or as entrepreneurs.”41 Entry-level nonprofit employees’ salaries are in the same range as those of educators and healthcare workers.

Student debt affects students of color and low-income students the most. A recent study by Demos showed that associate’s degree borrowing has spiked particularly among black students over the past decade, that black and Latino students are dropping out with debt at higher rates than white students.42

The impacts of student loan debt on society and the people affected are profound. One of the many impacts of student loan debt on progressive nonprofits could be the systematic blocking of an entire generation of diverse emerging leaders accessing the progressive leadership pipeline. An article in The Journal of Public Economics from 2011 by Jesse Rothschild (a professor of economics at UC Berkeley) and Cecilia Elena Rouse (professor of economics and public affairs at the Woodrow Wilson School at Princeton) used a natural experiment to find the causal link between student debt and employment outcomes. The authors find that student debt causes graduating students to choose occupations with higher salaries, while “decreasing the probability that students choose low-paid public interest jobs.”43

While Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) programs exist, they only apply to employees of 501(c)(3) organizations who’ve worked at qualifying organizations for ten years.44 Labor unions, 501(c)(4)s, and political organizations are excluded. While leadership development programs can be easily funded with 501(c)(3) dollars, it would be unwise to steer progressive top talent into the one type of organization not allowed political speech.

This barrier can have a substantial impact on the movement itself. It could limit the membership of public interest nonprofit groups that are doing progressive organizing. This is especially concerning if it limits the ability of working class students and students of color from participating in the very organizations whose missions are to empower these groups.

For example, the labor movement and alt-labor groups would be at a disadvantage if they cannot recruit and develop leaders from students with a working class background; lived experience combined with training and leadership development are key to a strong movement. The labor movement also needs young activists in its ranks to maintain vitality over time and further institutionalizes social justice and community unionism into its practices.45 Programs like Union Summer46 and the examples from the labor movement in the previous section demonstrate that young organizers will be invaluable in developing labor’s strategy for the 21st century economy. If structural barriers exist that prevent diversity from reaching these progressive organizations, those organizations face a problematic contradiction of trying to empower groups that are not represented in their organizations.

Conservatives Remain Focused on Students and Campuses

On August 23, 1971, two months prior to being nominated to serve on the Supreme Court of the United States, Lewis F. Powell, Jr. mailed a confidential memorandum to his friend at the Chamber of Commerce. The memo, titled “Attack on American Free Enterprise System”—and eventually known as “the Powell Memorandum—outlined ways in which business should defend and counterattack against a “broad attack” from “disquieting voices,” such as Ralph Nader. He argued that “there is reason to believe that the campus is the single most dynamic source” of the attack.47

Enter the Koch Brothers. Charles Koch, in his speech “Anti Capitalism and Business” at George Mason University in 1974, cited the Powell Memorandum in his discussion of his funding strategies with campuses:

“[W]e have supported the very institutions from which the attack on free markets emanate. Although much of our support has been involuntary through taxes, we have also contributed voluntarily to colleges and universities on the erroneous assumption that this assistance benefits businesses and the free enterprise system, even though these institutions encourage extreme hostility to American business. We should cease financing our own destruction and follow the counsel of David Packard, former Deputy Secretary of Defense, by supporting only those programs, departments or schools that ‘contribute in some way to our individual companies or to the general welfare of our free enterprise system.’”48

In recent years, between 2005 and 2014, the Charles Koch Foundation spent $109.7 million on 361 distinct campuses, according to IRS filings from Koch’s nonprofit foundations.49 The grants from the foundation are to promote libertarian policy, and in some cases, give the Kochs the authority to veto the hiring of professors that they fund.50 The Kochs devoted some $30 million to George Mason University alone, much of going to the Mercatus Center, a resolute anti-regulatory think tank with connections to the similarly conservative economics department. The Institute for Human Studies was also bankrolled by the Kochs. Jane Mayer51 writes:

“The IHS was founded by F. A. “Baldy” Harper, a free-market fundamentalist who… had written essays for The Freeman, calling taxes “theft,” welfare “immoral,” and labor unions “slavery” and opposing court-ordered remedies to racial segregation… Anxious at one point that the war of ideas was proceeding too slowly, Charles [Koch] reportedly demanded better metrics with which to monitor students’ political views…applicants’ essays had to be run through computers in order to count the number of times they mentioned the free-market icons Ayn Rand and Milton Friedman. Students were tested at the beginning and the end of each week for ideological improvement.”

The Kochs weren’t alone. Four other major foundations generously funded universities to implement or go beyond the recommendations of the Powell Memorandum: the Scaife Foundation, the John M. Olin Foundation, the Bradley Foundation, and the Adolph Coors Foundation.52

In addition to funding universities directly, these foundations have bankrolled a sprawling youth movement. According to the Center for American Progress, between 1999 and 2003, right-wing foundations granted nearly $173 million to the top eleven conservative youth leadership organizations. The same analysis demonstrated that in 2012, conservative youth organizations had 60 percent more staff than progressive youth organizations as well as more diversified fundraising programs. In addition, conservative youth organizations mostly offer paid internship and fellowship opportunities, while few progressive organizations can or do offer the same opportunities.53

The Solution

Blue Oceans: New Strategic Thinking

A “Blue Ocean” strategy emphasizes the need for organizations to add new attributes to their programs in order to create new funding spaces and sustain rapid growth. Under a Blue Ocean strategy, an organization’s ability to remain a top-tier player depends more upon its degree of innovation than the traditional notion of head-to-head competition. A Blue Ocean strategy is driven by the process of maintaining high-value, inexpensive elements of an organization’s current offerings, stripping out low-value expensive components, and adding innovative high-value offerings; thus, creating a product that is in great demand but is not stuck in its old market; it can tap several markets where the older offering was not competing before.

One of Kim and Mauborgne’s prime examples of a Blue Ocean strategy in their book54 was Cirque du Soleil. As they explained, circuses historically had a set of low cost, high value features, such as acrobatics (high value) and tents (high value, low cost). They had increasingly controversial, high cost elements as well (animals). Cirque du Soleil stripped out the animal component, kept the tent as a low-cost venue, and significantly invested in the acrobatics, adding on additional theatrical elements. These theatrical elements resulted in Cirque du Soleil existing in a new market space, occupying part of the circus market, part of theater’s market, and attracting entirely new consumers as well. Cirque du Soleil was able to charge theater prices (more expensive) while costing less than a circus (lower cost), creating a new, highly profitable space in which there was no competition.

In contrast to pursuing a Blue Ocean fundraising strategy, most nonprofit organizations compete for funds in known, competitive fundraising spaces where financial returns decrease as competition grows. Traditional fundraising and even member benefits like the AFL-CIO’s credit card offering all eventually decline as competition from nonprofit or for-profit corporations grows. These spaces, which can include direct mail, email, conventional canvass programs, member benefits, earned revenue, or foundation fundraising, are often characterized by cut-throat competition, like a feeding frenzy in a shark tank (a so-called “red ocean”).

A Blue Ocean fundraising strategy, in comparison, would involve offering unique, higher-value programs to donors to tap into entirely new funding markets, such as combining the mission related benefits of training leaders with scholarships, both of which foundations currently fund.

Scholarships: The $44 Million Dollar Blue Ocean

Amidst the reality that the right is out-raising progressive student groups, the instability of funding for youth on the left, and the crisis in the pipeline for diverse emerging leaders for the nonprofit progressive sector, there is an untapped blue ocean of opportunity for developing the next generation of diverse, progressive civic leaders.

The Progressive Pipeline Scholarship Fund

But independent and uncoordinated activity by individual [foundations], as important as this is, will not be sufficient. Strength lies in organization, in careful long-range planning and implementation, in consistency of action over an indefinite period of years, in the scale of financing available only through joint effort, and in the political power available only through united action and national organizations.

–Lewis J. Powell, The Powell Memorandum

In order to explore the hypothesis that scholarships can be one of the major Blue Ocean strategies for the progressive nonprofit sector, we compiled nonprofit foundations with a history of progressive grant making to estimate the dollar value of annual scholarship giving. Using the Foundation Directory Online database, 120 foundations with stated commitments to social justice, economic justice, the environment and human rights were included in the study. We analyzed tax documentation (Form 990s), annual reports, and websites to estimate annual scholarship giving. The annual scholarship giving was determined from the most recently available Form 990s for each foundation (ranging from fiscal years 2012–15). General education funds, and individual donors were not included in the estimates. Community foundations were largely excluded as well. We found that these foundations contributed about $44 million to scholarships for various students and programs.

Community foundations (twenty-five of the total 120 foundations analyzed) were conservatively estimated, as these foundations have separate funds managed by individual donors that can direct money according to their interests. The only scholarship funds at community foundations that were explicitly devoted to our issue areas were included in the estimate.

For private and corporate foundations, we summed the total scholarship dollars spent if the scholarships were controlled entirely by that foundation and the foundation had a progressive mission.

In total, these 120 foundations surveyed contributed an annual $44 million in scholarships to various students and programs. This dollar amount can be considered the Blue Ocean that is, in some years, equal to or greater than the total funding for community organizing of youth. Each of these foundations had stated commitments to our interest areas on their website or on the Foundation Directory Online database. Some of the scholarships that were disbursed by these foundations were to scholarships with an explicit social justice focus, but many were to scholarship funding without explicit social justice requirements.

It should be noted that this dollar estimate is the maximum estimate of the market for organizer scholarship funds from these foundations, but this does not include major donors, middle donors, or small donors. We also believe that more resources are available at the community foundation level and through other Donor Advised Funds.

Since our estimate includes the total amount of money that the foundations donate in scholarships each year, the $44 million figure is an approximation of the per year total pool of money available for reallocation to scholarships for progressive organizers from foundations. Only a small fraction of the estimated scholarship amount is necessary to fund a progressive organizing scholarship program of the scope envisioned in this paper ($3 million a year to build towards a $30 million endowment over ten years). As such, the dollar amount should be seen as a proof of concept, not a concrete estimate of the money that would be directly allocated to the fund.

This dollar amount may be the Blue Ocean that progressive youth organizing needs. If a fraction of these foundations were to target their scholarships to fund tuition, expenses, internships, fellowships, and work-study opportunities through which students work on progressive campaigns, these scholarships could enable foundations to leverage their current giving to have a greater impact on the issues facing society today.

While it is out of the scope of this paper to outline the plan for the redirection of scholarship funds, progressive should heed the advice of Lewis Powell over forty years ago, who argued that funds are best be deployed in an orchestrated way. In this case, a new scholarship strategy should achieve the following:

- Tap the vast wealth of knowledge that foundations have developed in running scholarship programs;

- Reduce redundant overhead by joining forces to recruit and select students and administer scholarship funds; and

- Tap into existing programs at colleges, in student networks, and with advocacy organizations for training and real world experience in campaigns, internships, and fellowships to provide students with the skills and connections needed to be positions for jobs after graduation.

In addition, any successful program would need to apply best practices to examine how scholarship programs, tied to mentorship, team building, trainings, funding multiple students on each campus who support one another, and other techniques can increase the number of students who graduate and who remain active as agents of change through their studies and beyond.

What this potential Blue Ocean does represent is a ray of hope. A ray of hope that the pipeline to progressive leadership needs not remain shut to low income students and students of color. A ray of light that the essential role of developing the change agents of today and the next few decades will no longer be subject to the fluctuations of a market driven down by terrorist attacks or a broken banking system. A ray of hope that we can count on a future filled with more young leaders, who as history shows, are most often the courageous leaders who step forward and push society further toward justice than their elders thought, in the moment, was possible.

Notes

- “About Turning Point USA,” Turning Point USA, Accessed March 31, 2017, https://tpusa.com/aboutus/.

- “Key Facts on Social Justice Grantmaking” Foundation Center, Accessed April 12, 2017, http://foundationcenter.issuelab.org/resource/key_facts_on_social_justice_grantmaking_2011.

- Renee Mauborgne and W. Chan Kim, Blue Ocean Strategy: How to Create Uncontested Market Space and Make the Competition Irrelevant, Harvard Business Review Press, 2004.

- Shayna Strom, “Organizing’s Business Model Problem,” The Century Foundation, October 26, 2016, https://tcf.org/content/report/organizings-business-model-problem/.

- Jennifer Jihye Chun, George Lipsitz, and Young Shin, “Intersectionality as Social Movement Strategy: Asian Immigrant Women Advocates,” Signs 38 (2013):4, http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/669575.

- Natasha Geiling, “The environmental movement grapples with social justice under Trump,” ThinkProgress, December 23, 2016, https://thinkprogress.org/the-environmental-movement-grapples-with-social-justice-in-the-age-of-trump-d0cb863c7996.

- Kenneth Andrews, Marshall Ganz, Matthew Baggetta, Hahrie Han, and Chaeyoon Lim, “Leadership, Membership, and Voice: Civic Associations that Work,” American Journal of Sociology 115 (January 2010):4, http://scholar.harvard.edu/hahrie/files/AndrewsEtAl2010.pdf.

- David V. Day, “Leadership Development: A Review in Context,” Leadership Quarterly 11 (2001):(4, http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1048984300000618.

- Marshall Ganz and Toby Jenkins, “Building Community Cultural Leadership,” Cultural Organizing, August 5, 2013, Accessed March 31, 2017, http://culturalorganizing.org/tag/marshall-ganz/.

- Jo Freeman, “On the Origins of Social Movements,” in Waves of Protest: Social Movements Since the Sixties, ed. Jo Freeman and Victoria Johnson, (Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield, 1999), 7–24.

- Monica Davey and Steven Greenhouse, “Angry Demonstrations in Wisconsin as Cuts Loom,” New York Times, February 16, 2011, Accessed March 31, 2017, http://www.nytimes.com/2011/02/17/us/17wisconsin.html.

- Tara Fiorito, “Dreamers Unbound: Immigrant Youth Mobilizing,” New Labor Forum, January 19, 2015, http://newlaborforum.cuny.edu/2015/01/19/dreamers-unbound-immigrant-youth-mobilizing/.

- Carson, Clayborne, In Struggle: SNCC and the Black Awakening of the 1960s, Harvard University Press, 1981.

- Fossil Fuel Divestment Student Network, Accessed March 31, 2017, http://www.studentsdivest.org/.

- Sascha Cohen, “Why the Woolworth’s Sit-In Worked,” TIME, February 2, 2015, http://time.com/3691383/woolworths-sit-in-history/.

- Cassandra Spratling, “2 Other Bus Boycott Heroes Praise Parks’ Acclaim,” Chicago Tribune, November 16, 2005, http://articles.chicagotribune.com/2005-11-16/features/0511160360_1_rosa-parks-city-bus-bus-boycott.

- Costanza-Chock, Sasha, “Youth and Social Movements: Key lessons for allies,” SSRN, December 17, 2012, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2199531.

- Bausum, Ann. Freedom riders: John Lewis and Jim Zwerg on the front lines of the Civil Rights Movement. Recorded Books, 2008.

- Richard Knight, “Sanctions, Disinvestment, and U.S. Corporations in South Africa,” ed. Robert E. Edgar, Sanctioning Apartheid (Africa World Press, 1990), http://richardknight.homestead.com/files/uscorporations.htm.

- Ibid.

- Ross Gelbspan, “RIP: Global Climate Coalition (March, 200),” Industry Defections Decimate Global Climate Coalition, The Heat is Online, October 15, 2016, http://www.heatisonline.org/contentserver/objecthandlers/index.cfm?ID=4468&Method=Full.

- The Movement for Black Lives, “A Vision for Black Lives,” Accessed March 31, 2017, https://policy.m4bl.org/.

- Michael Pearson, “A Timeline of the University of Missouri Protests,” CNN, November 10, 2015, http://www.cnn.com/2015/11/09/us/missouri-protest-timeline/.

- The Movement for Black Lives, “Policy Platform,” Accessed March 31, 2017, https://policy.m4bl.org/platform/.

- United Students Against Sweatshops, “About,” Accessed March 31, 2017, http://usas.org/about/.

- Student Labor Action Project, “About,” Accessed March 31, 2017, http://studentlabor.org/about/.

- Dave Eisenstadter, “State Rules that Peer Mentors at UMass May Vote on Joining Resident Assistant Union,” Daily Hampshire Gazette, February 23, 2015, http://www.gazettenet.com/Archives/2015/02/UMassUnion-hg-022415.

- United Auto Workers Local 2322, “Resident Assistants, UMass Amherst,” Accessed March 31, 2017, https://uaw2322.org/ra/.

- Avery Fürst, “Wait, that was SLAP?” The Massachusetts Daily Collegian, April 17, 2013. http://dailycollegian.com/2013/04/17/wait-that-was-slap/.

- Hannah Natanson, “Hundreds of Students Leave Class to Support HUDS Strike,” The Harvard Crimson, October 18, 2016, http://www.thecrimson.com/article/2016/10/18/huds-supporters-walk-out/.

- Katheleen Conti and Adam Vaccaro, “Harvard, striking dining hall workers make deal,” The Boston Globe, October 25, 2016, https://www.bostonglobe.com/business/2016/10/25/harvard-university-striking-dining-hall-workers-reach-agreement/g29IASHQz4ClwY0zT5QD7M/story.html.

- Colleen Flaherty, Colleen, “NLRB: Graduate Students at Private Universities May Unionize,” Inside Higher Ed, August 24, 2016, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2016/08/24/nlrb-says-graduate-students-private-universities-may-unionize.

- Jonah Engel Bromwich and Liz Robbins, “Faculty Lockout at L.I.U.-Brooklyn Ends With Contract Agreement,” New York Times, September 14, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/15/nyregion/faculty-lockout-at-liu-brooklyn-ends-with-contract-agreement.html?_r=0.

- Kasia Kovacs, “Faculty Strike at 14 Campuses,” Inside Higher Ed, October 20, 2016, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2016/10/20/disagreements-over-wages-and-health-care-cause-pennsylvania-faculty-members-strike.

- Deborah Ziff, “On Campus: UW-Madison students to Walker: “Don’t Break My ♥,” Wisconsin State Journal, February 14, 2011,

http://host.madison.com/wsj/news/local/education/on_campus/article_87a7eaa0-3853-11e0-bcc7-001cc4c002e0.html. - Duncan Meisel, “Case Study: Wisconsin Capitol Occupation,” Beautiful Trouble, http://beautifultrouble.org/case/wisconsin-capitol-occupation/.

- Jane Collins, “Theorizing Wisconsin’s 2011 Protests,” American Ethnologist 39 (February 2012):1, http://dces.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/30/2013/08/collins-wisconsin-protests.pdf.

- Nick Crossley, “Social Networks and Student Activism: on the Politicizing Effects of Campus Connections,” The Sociological Review 56 (2008):1, http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1467-954X.2008.00775.x/full.

- Nella,Van Dyke, “Hotbeds of Activism: Locations of Student Protest,” Social Problems 45 (May 1998):2, https://www.jstor.org/stable/3097244.

- Christian Sweeney, Deputy Organizing Director, AFL-CIO, Interview by Philip Radford. Washington, D.C., October 20, 2016.

- The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, “Student loan servicing Analysis of public input and recommendations for reform,” September 2015, http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201509_cfpb_student-loan-servicing-report.pdf.

- Mark Huelsman, “The Debt Divide: The Racial and Class Bias Behind the ‘New Normal’ of Student Borrowing,” Demos, May 19, 2015, http://www.demos.org/publication/debt-divide-racial-and-class-bias-behind-new-normal-student-borrowing.

- Jesse Rothstein and Cecilia Elena Rouse, “Constrained after College: Student Loans and Early-career Occupational Choices,” Journal of Public Economics 95 (2011): 1–2, 149-63. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2010.09.015. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0047272710001337.

- Mark Zuckerman, “Student Loan Borrower Relief Hiding in Plain Sight,” The Century Foundation, July 21, 2016, https://tcf.org/content/report/student-loan-borrower-relief-hiding-plain-sight/.

- Janice Fine, “Community unions and the revival of the American labor movement,” Politics & Society 33, no. 1 (2005): 153-199, http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0032329204272553.

- Nella Van Dyke, Marc Dixon and Helen Carlon, “Manufacturing Dissent: Labor Revitalization, Union Summer and Student Protest.” Social Forces 86, (2007): 1, 193-214, https://academic.oup.com/sf/article-abstract/86/1/193/2234937/Manufacturing-Dissent-Labor-Revitalization-Union.

- “Powell Memorandum: Attack on American Free Enterprise System,” Powell Archives, Washington and Lee University School of Law, August 23, 1971, http://law2.wlu.edu/deptimages/Powell%20Archives/PowellMemorandumPrinted.pdf.

- Charles Koch, “Anti Capitalism and Business” Speech to Institute for Humane Studies Board of Directors, 1974, https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/1302373-1974-charles-koch-ihs-speech-anti-capitalism-and.html.

- Connor Gibson and Lindsey Harris, “Koch Pollution on Campus, Academic Freedom Under Assault from Charles Koch’s $50 Million Campaign to Infiltrate Higher Education,” Greenpeace, accessed October 16, 2016. http://www.greenpeace.org/usa/global-warming/climate-deniers/koch-pollution-on-campus/.

- Scott Jaschik, “Who Controls a Grant?,” Inside Higher Ed, May 11, 2011, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2011/05/11/debate_at_florida_state_over_grants_from_koch_foundation_and_requirements_attached_to_funds.

- Jane Mayer, Dark money: The hidden history of the billionaires behind the rise of the radical right, Doubleday, 2016.

- Ibid.

- Anne Johnson and Tobin Van Ostern, “Comparing Conservative and Progressive Investment in America’s Youth,” Center for American Progress and Campus Progress, December 6, 2012, https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/democracy/reports/2012/12/06/47100/comparing-conservative-and-progressive-investment-in-americas-youth/.

- Renee Mauborgne and W. Chan Kim, Blue Ocean Strategy: How to Create Uncontested Market Space and Make the Competition Irrelevant, Harvard Business Review Press, 2004.