Now, more than two years after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, workers, academics, and policymakers alike are still figuring out its full implications on the U.S. labor market. Going forward, understanding what changes occurred, which ones are temporary and which are permanent, and what the labor market will look like in the years ahead will be of great importance for the well-being of U.S. families and the broader economy.

Dubbed by many observers not as a recession but as a “shecession,”1 the COVID-19 pandemic’s effects on U.S. society and the economy—including school closures,2 child care disruptions,3 shifting caregiving responsibilities,4 and massive layoffs in the service and hospitality sectors,5 among others—have been disproportionately borne by women. Intersecting oppressions, including structural and ongoing racism, mean the impacts are felt even more by Black, Latina, and immigrant women. While the personal effects of these challenges have been clear from the start, the ways in which they translate to the labor market, families’ economic security, and the economic recovery are areas for further study.

For example, a new working paper6 by Harvard University’s Claudia Goldin finds that, contrary to some expectations, women overall did not significantly exit the labor force or reduce their work relative to men during the COVID-19 pandemic. The COVID-19 recession was a “shecession,” Goldin finds, not because women fared much worse than men in aggregate employment or labor force participation, but because women were more affected relative to past recessions, which traditionally spared women-led sectors of the economy to a greater degree. While many women remained in the workforce over the past two years, the added stress of the pandemic, caregiving responsibilities, household duties, and remote schooling—piled on top of regular employment—disproportionately took a toll on women’s well-being and mental health.7

Of course, aggregate data do not speak to the varied labor market experiences of working women across the United States. Workers of color,8 parents,9 and other caregivers, workers with lower educational attainment,10 those relying on part-time employment, and those employed in certain occupations faced worse labor market outcomes than the aggregate or averages suggest. The mechanisms that contributed to these disparities require continued study both to better understand them and to help craft an appropriate policy response.

The Century Foundation and the Washington Center for Equitable Growth co-hosted the Women’s Racial and Economic Justice Roundtable, bringing together more than forty leading policy experts and academics to share data, identify key research questions, and discuss promising strategies for future studies.

To provide further clarity on the U.S. labor market for women in the pandemic era, The Century Foundation and the Washington Center for Equitable Growth co-hosted the Women’s Racial and Economic Justice Roundtable, bringing together more than forty leading policy experts and academics to share data, identify key research questions, and discuss promising strategies for future studies. This report summarizes the key themes and research questions identified at this roundtable, as well as key recommendations for researchers that came out of the event.

How Caregiving Responsibilities Impact Labor Market Decisions and Well-Being for Women and Their Families

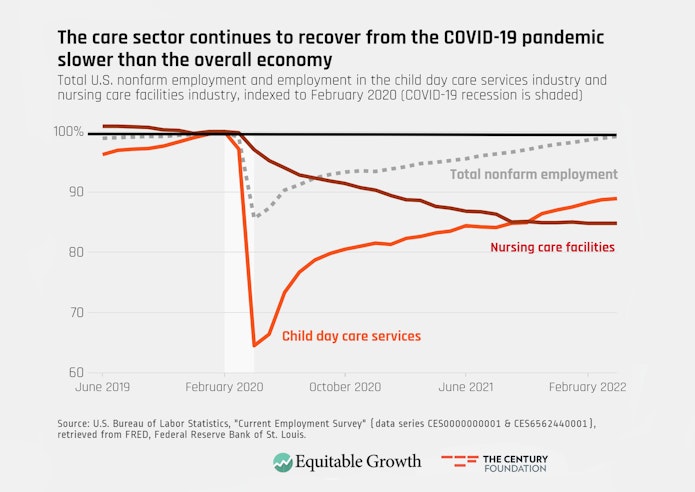

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, preexisting fault lines in the U.S. child care market—long plagued by a lack of public investment, leading to high prices, limited access, and low wages—fully ruptured. In the early months of the crisis, lockdowns and stay-at-home orders temporarily shuttered some care providers to slow the initial spread of the virus; some never reopened.11 As the pandemic dragged on, families were forced to make difficult choices around their child care needs amid public health and safety concerns. Today, employment in the child care sector remains roughly 12 percent below pre-pandemic levels, exacerbating the preexisting capacity crunch for families seeking child care.12

Care challenges amid the pandemic were not restricted to parents with children. Half of adults caring for a parent or other loved ones faced disruptions in their normal caregiving arrangements due to the pandemic.13 Women and caregivers of color were more likely to face such disruptions, which were associated with higher levels of mental health challenges and job losses.14

Despite these well-documented challenges, further research is needed on how these care responsibilities impacted women’s labor force participation, including work hours, job quality, and overall economic stability, and how that impact varied by racial demographics, family structure, education level, and other characteristics. Roundtable participants suggested that these insights could best be provided by longitudinal or long-term research on this topic. For example, research by roundtable participant Misty Heggeness and others at the Minneapolis Federal Reserve documents how mothers of school-aged children fared similarly to fathers at the start of the pandemic—tenuously balancing work, remote schooling, and child care—but as the pandemic dragged on, mothers who worked remotely were less likely to be actively working, compared to fathers.15 Such trends would be invisible with research restricted to shorter time-horizons.

Insufficient Data and Imprecise Research on Women of Color Obscures the Current State of the Labor Market

As with past downturns, the COVID-19 recession has been particularly harmful for workers of color, due to a combination of sector-specific job losses in leisure and hospitality early in the pandemic, preexisting inequalities that make economic shocks more difficult for people of color to weather, and systemically racist practices that impede access to income support programs.16 As of April 2022, the seasonally adjusted unemployment rates for Black women (5 percent) and Latina women (3.8 percent) were well above the 2.8 percent rate for White women.

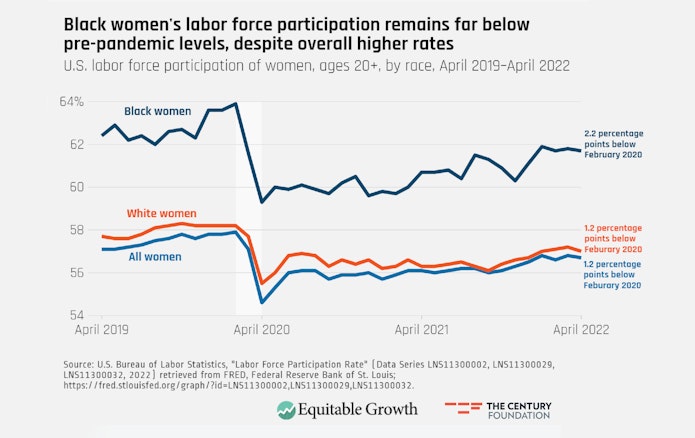

Other data points suggest a more complicated story—at least initially. Black women, and particularly Black mothers, for example, historically have had a consistently higher labor force participation rate than White mothers. Part of the reason for this difference is clear: policy choices, current laws, and related factors ensure that Black women have needed to work as a matter of economic necessity. A persistent racial wealth gap born from the legacy of slavery and systemic racism, coupled with the fact that two-thirds of Black mothers are the sole or primary breadwinner of their household, compared to only one-third of White mothers, yield greater paid labor among Black women.17 Yet despite having an overall higher labor force participation rate, Black women’s labor force participation is down 2.2 percentage points from February 2020, compared to 1.2 percentage points for White women. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

A lack of data on workers of color may be obscuring any remaining challenges in the pandemic labor market that would illuminate people’s lived experiences. Such data limitations include the mismatch of data sets that look at relevant variables and a lack of longitudinal data that would follow the same individuals over time to understand how they have fared in the crisis brought on by the pandemic. Roundtable participants stressed the importance of the careful selection of employment outcomes, longitudinal research, and nontraditional data sources to overcome gaps in data for policymakers and researchers to accurately understand the nuances of the labor market experiences of women of color.

In April 2022, for example, employment for Hispanic or Latina women ages 20 and up was just slightly higher than its pre-pandemic level in absolute terms—11,839,000 employed women, compared to 11,831,000 in February 2020—but this number obscures the relative within-group experience of these women in the pandemic labor market.18 While higher total employment is certainly a boon for the economy, these figures do not consider the population growth that occurred during the pandemic, and this statistic overstates the recovery for Hispanic women and Latinas. The employment-to-population ratio—the ratio of the current civilian labor force against the total working age population—for this group of women workers, for instance, has fallen from 59.1 percent to 56.8 percent over that same period.19

Likewise, the lack of accessible longitudinal data that include detail on care responsibilities and labor market outcomes makes it difficult to conduct research to understand how the care shock of the early pandemic subsequently shaped people’s employment.

Finally, data on racial and ethnic groups that have relatively smaller populations in the United States, including American Indians and Alaska Natives, are not always collected consistently or in large enough samples for scholars to conduct empirical research that reflects population levels due to lack of statistical significance.20 The monthly Employment Situation Summary published by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics only recently began publishing data that includes American Indians and Alaska Natives, but these data are not seasonally adjusted due to small sample sizes, so it is difficult to interpret month-over-month variation.

Do Declines in “Pink Collar” Jobs Stem From Lower Worker Supply or Employer Demand?

The unique nature of the COVID-19 recession resulted in atypical patterns of job loss, compared to prior recessions. Industries that were once more recession-resistant couldn’t avoid the economic challenges arising from reduced public demand for in-person services, temporary business closures, and the swift and deep recession. During the Great Recession of 2007–2009, for example, construction and durable goods manufacturing—two sectors employing primarily men—suffered the worst losses amid the housing market crisis. During the COVID-19 recession, on the other hand, leisure and hospitality, health and educational services, and retail—sectors that more often employ women, also known as “pink collar” jobs—faced the deepest declines.21

Not all of these jobs have returned. Even though care needs within families do not follow business cycles, many care-sector jobs remain below their pre-pandemic levels. Some of these industries employing primarily women, such as nursing care, are still losing jobs, while others, such as child care, are well below their pre-pandemic levels—even as the rest of the labor market is nearing a full recovery. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Roundtable participants discussed some reasons why this might be the case. A common public narrative is that these job openings and losses stem from lower labor supply, or a “worker shortage,” in which workers are unwilling to return to jobs in these sectors due to issues of low pay, poor job quality, or other opportunities. At the roundtable, however, participants explored a different explanation: perhaps these sectors have reduced their labor demand in ways economists have not observed in past recessions.

In previous recessions, heavily impacted industries often experienced a realignment of their labor supply needs as low-productivity firms exited the market, business practices and processes were reconfigured to reduce labor costs, and employees exited the labor force or delayed entry to the labor market. Among those industries heavily burdened by the Great Recession, for example, manufacturing never returned to pre-2007 employment levels, and construction had only just recovered when the COVID-19 recession hit.

Meanwhile, the industries most impacted by the COVID-19 recession have faced no such long-term depression from past recessions but face unique challenges in their rebound, including the persistent public health crisis and inherent market failures that threaten their stability.22

While job openings in heavily impacted sectors are currently high, this trend does not rule out the potential that the pandemic induced a shift in labor demand.23 Indeed, roundtable participants predicted more demand-driven reductions in sectors that employ more women than public discourse suggests and stressed the need for closer investigation of this topic. Attendees recommended that researchers employ empirical techniques such as probability models on the likelihood of working and mixed-methods research that includes both in-depth, qualitative surveys and broad population surveys as potential means for exploring this topic and understanding the supply- and demand-side factors that shape current labor market outcomes.24

The Fiscal Policy Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic May Be Exacerbating Racial and Gender Gaps in the Labor Market

The sudden onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 required a quick and robust policy response. While this policy response surely blunted the impact of the pandemic on the economy, preexisting deficiencies in income support programs and unintended flaws in new pandemic-specific programs may have resulted in an unequal recovery for women, and particularly women of color.

Eligibility requirements and application hurdles resulted in lower rates of access and recipiency of unemployment insurance for women relative to men25 and Black workers relative to White workers.26 Meanwhile, small businesses, such as family child care homes and Black- and Hispanic-owned businesses, faced significant hurdles27 accessing the Paycheck Protection Program28 yet were disproportionately impacted by the pandemic.

Despite these issues, roundtable participants were quick to point out that many programs were successful in supporting public health and the economy throughout the pandemic in the United States. Federally funded emergency paid leave helped flatten the curve29 of COVID-19 cases, and the Child Tax Credit significantly reduced childhood poverty30 and alleviated food insecurity.31 And flexible funding from the American Rescue Plan helped pull the child care industry32 back from the brink of collapse and support more families in need of home- and community-based services for their older and disabled loved ones.

Still, the future of the federal policy response to the COVID-19 recession and longer-term social policy investments are uncertain. Emergency paid leave and the Child Tax Credit have been allowed to expire, along with many other pandemic-era policies that shored up families’ economic security. Funding for child care relief will soon run out as well.

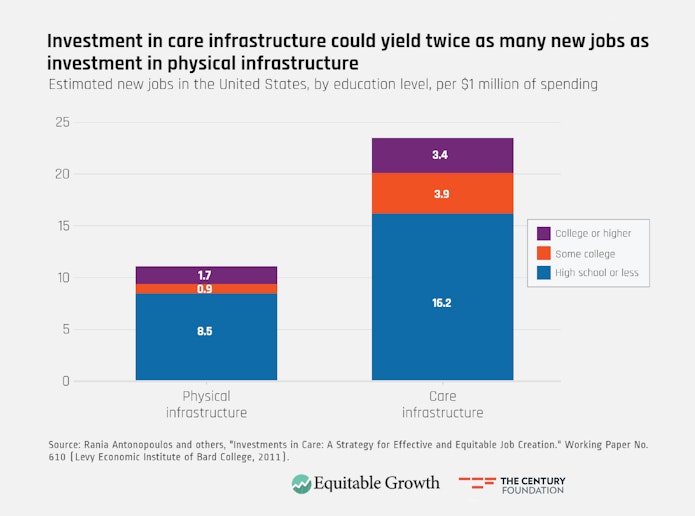

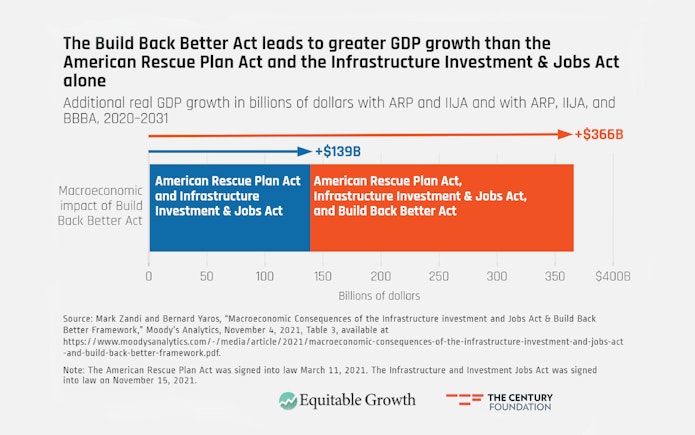

One factor contributing to the unevenness of the government’s policy response is that women have typically been segregated into historically undervalued occupations.33 While Congress was able to pass the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act,34 generating resources for industries such as construction and energy that employ more men, legislation that would invest in the economy by building a robust care infrastructure has stalled. These investments in the care economy, including child care and home health, would have benefited women more, while also generating more jobs and growing the economy more than physical infrastructure investments alone. (See Figures 3 and 4.)

Figure 3

Figure 4

Roundtable participants suggested that while much is already known about the policies enacted or expanded during the pandemic, future research could shed light on how these policies impacted specific communities. At the root of many remaining research questions is the issue of data, including data on the distributional effects of the government’s fiscal policy response, the utilization of emergency paid leave, and the disbursement of Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security, or CARES, Act and American Rescue Plan Act funding. Beyond that, roundtable attendees agreed that researchers should highlight the experiences of those who are disproportionately impacted by the policy response but largely removed from the policymaking process, including, but not limited to, women of color, parents with young children, and immigrant workers.

Looking Forward

The economic story of the COVID-19 pandemic is still being written, but the health of the economy and economic equity for women and workers of color requires a nuanced understanding of the U.S. labor market today. Several things are clear: the COVID-19 recession impacted women, and particularly women of color, to a greater degree than past recessions; several industries that primarily employ women are still facing the economic fallout of the pandemic more than two years later; and the unique nature of the pandemic exacerbated caregiving challenging that primarily fall on women.

Still, important questions remain. How are child care and other caregiving duties translating to women’s labor market outcomes and personal well-being, including mental health? How much of lingering reductions in employment stem from labor demand as opposed to labor supply? What changes to the labor market are permanent, and which will revert to their pre-pandemic state? What are the short- and long-term impacts of the federal government’s uneven fiscal policy response?

Participants in the recent roundtable co-hosted by the Washington Center for Equitable Growth provided several key recommendations for researchers as they seek to answer these questions, including:

- conducting longitudinal and long-term research;

- cultivating nontraditional data sources to overcome gaps in data;

- using careful selection of data and measures to accurately understand the nuances of the labor market experiences of women of color;

- employing empirical techniques, such as probability models and mixed-methods research, to better understand factors that shape our current labor market outcomes; and

- engaging in research that highlights the experience of women disproportionately impacted by public policy but largely locked out of the policymaking process.

By convening leading academics, policy experts, and advocates for the Women’s Racial and Economic Justice Roundtable, we have begun to refine the research agenda on racial and gender equity in the pandemic-era labor market and stimulate new research that will inform equitable policy solutions. Such evidence-backed policies are essential to the recovery from the COVID-19 recession and to position U.S. workers and families to share in sustainable, broad-based economic growth.

Notes

- Alisha Haridasani Gupta, “Why Some Women Call This Recession a ‘Shecession,’” New York Times, May 9, 2020

(updated June 18, 2021), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/09/us/unemployment-coronavirus-women.html. - Titan Alon Matthias Doepke Jane Olmstead-Rumsey Michèle Tertilt, “The Impact Of Covid-19 On Gender Equality,” National Bureau Of Economic Research, April 2020, https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w26947/w26947.pdf.

- Sam Abbott, “Child care is essential for working parents, but is the industry ready and safe to reopen?” Washington Center for Equitable Growth, July 16, 2020, https://equitablegrowth.org/child-care-is-essential-for-working-parents-but-is-the-industry-ready-and-safe-to-reopen/.

- Yulya Truskinovsky, “Coronavirus disruptions in family caregiving highlight the importance of investments in U.S. care infrastructure and paid leave,” Washington Center for Equitable Growth, August 24, 2021, https://equitablegrowth.org/coronavirus-disruptions-in-family-caregiving-highlight-the-importance-of-investments-in-u-s-care-infrastructure-and-paid-leave/.

- Kate Bahn and Carmen Sanchez Cumming, “Most recent JOLTS release provides latest data on how the coronavirus recession is different from the Great Recession,” Washington Center for Equitable Growth, August 10, 2020, https://equitablegrowth.org/most-recent-jolts-release-provides-latest-data-on-how-the-coronavirus-recession-is-different-from-the-great-recession/.

- Claudia Goldin, “Understanding The Economic Impact Of Covid-19 On Women,” National Bureau Of Economic Research, April 2022, https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w29974/w29974.pdf.

- Nina Vindegaard and Michael Eriksen Benros, “COVID-19 pandemic and mental health consequences: Systematic review of the current evidence,” Brain Behav Immun. October 2020, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7260522/.

- Kate Bahn and Carmen Sanchez Cumming, “Jobs report: a year into the coronavirus recession, employment losses have been greatest for Black women workers and Latinx workers,” Washington Center for Equitable Growth, March 5, 2021, https://equitablegrowth.org/jobs-report-a-year-into-the-coronavirus-recession-employment-losses-have-been-greatest-for-black-women-workers-and-latinx-workers/.

- Misty L. Heggeness, Jason Fields, Yazmin A. García Trejo And Anthony Schulzetenberg, “Tracking Job Losses for Mothers of School-Age Children During a Health Crisis,” United States Census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/03/moms-work-and-the-pandemic.html.

- Steven M. Fazzari and Ella Needler, “US Employment Inequality in the Great Recession and the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Institute for New Economic Thinking, March 31, 2021, https://www.ineteconomics.org/uploads/papers/WP_154-Fazzari-Needler-Emp.pdf.

- Sam Abbott, “The Child Care Economy,” Washington Center for Equitable Growth, September 15, 2021, https://equitablegrowth.org/research-paper/the-child-care-economy/.

- Carmen Sanchez Cumming and Kathryn Zickuhr, “February Jobs Day report: U.S. employment growth is still strong, but some care sector workers are being left behind,” Washington Center for Equitable Growth, March 4, 2022, https://equitablegrowth.org/february-jobs-day-report-u-s-employment-growth-is-still-strong-but-some-care-sector-workers-are-being-left-behind/.

- Yulya Truskinovsky, Jessica Finlay and Lindsay Kobayashi, “Caregiving in a Pandemic: COVID-19 and the Well-being of Family Caregivers 55+ in the U.S.” Washington Center for Equitable Growth, April 7, 2021, https://equitablegrowth.org/working-papers/caregiving-in-a-pandemic-covid-19-and-the-well-being-of-family-caregivers-55-in-the-u-s/.

- Yula Truskinovsky, “Coronavirus disruptions in family caregiving highlight the importance of investments in U.S. care infrastructure and paid leave,” Washington Center for Equitable Growth, August 24, 2021, https://equitablegrowth.org/coronavirus-disruptions-in-family-caregiving-highlight-the-importance-of-investments-in-u-s-care-infrastructure-and-paid-leave/.

- Misty Heggeness and Palak Suri, “Telework, Childcare, and Mothers’ Labor Supply,” Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, November 16, 2021, https://www.minneapolisfed.org/research/institute-working-papers/telework-childcare-and-mothers-labor-supply.

- Liz Hipple and Alix Gould-Werth, “Weak income support infrastructure harms U.S. workers and their families and constrains economic growth,” Washington Center for Equitable Growth, August 5, 2021, https://equitablegrowth.org/weak-income-support-infrastructure-harms-u-s-workers-and-their-families-and-constrains-economic-growth/.

- Sarah Jane Glynn, “ Breadwinning Mothers Are Critical to Families’ Economic Security,” Center for American Progress, March 29, 2021, https://www.americanprogress.org/article/breadwinning-mothers-critical-familys-economic-security/.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Employment Level – 20 Yrs. & over, Hispanic or Latino Women,” FRED/St. Louis Fed, April 2022, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?id=LNU02000035.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Employment Population Ratio – 20 and over, Hispanic or Latino Women,” FRED/St. Louis Fed, April 2022, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?id=LNU02300035.

- Gabriel R. Sanchez, Robert Maxim, and Raymond Foxworth, “The monthly jobs report ignores Native Americans. How are they faring economically?” Brookings, November 10, 2021, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/the-avenue/2021/11/10/the-monthly-jobs-report-ignores-native-americans-how-are-they-faring-economically/.

- Giuliana Scanni, “The Great Recession vs The Covid-19 Pandemic: Unemployment and Implications for Public Policy,” Bard, Spring 2021, https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1032&context=levy_ms.

- Sandra Black and Jesse Rothstein, “Public investments in social insurance, education, and child care can overcome market failures to promote family and economic well-being,” Washington Center for Equitable Growth, January 14, 2021, https://equitablegrowth.org/public-investments-in-social-insurance-education-and-child-care-can-overcome-market-failures-to-promote-family-and-economic-well-being/.

- Kathryn Zickuhr and Carmen Sanchez Cumming, “JOLTS Day Graphs: February 2022 Edition,” Washington Center for Equitable Growth, March 29, 2022, https://equitablegrowth.org/jolts-day-graphs-february-2022-edition/.

- Jasmine Tucker and Julie Vogtman, “Resilient but not Recovered: After Two Years of the COVID-19 Crisis, Women are Still Struggling, National Women’s Law Center, March 31, 2022, https://nwlc.org/resource/resilient-but-not-recovered-after-two-years-of-the-covid-19-crisis-women-are-still-struggling/.

- Eliza Forsythe and Hesong Yang, “Understanding Disparities in Unemployment Insurance Recipiency,” University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, November 12, 2021, https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/OASP/evaluation/pdf/University%20of%20Illinois%20-%20Final%20SDC%20Paper.pdf.

- Liz Hipple and Alix Gould-Werth, “Weak income support infrastructure harms U.S. workers and their families and constrains economic growth,” Washington Center for Equitable Growth, August 5, 2021, https://equitablegrowth.org/weak-income-support-infrastructure-harms-u-s-workers-and-their-families-and-constrains-economic-growth/.

- Marcus Baram, “‘That was it—silence’: As bailout funds evaporate, minority-owned businesses say they’ve been shut out,” Fast Company, Apri. 29, 2020, https://www.fastcompany.com/90498767/that-was-it-silence-as-bailout-funds-evaporate-minority-owned-businesses-say-theyve-been-shut-out.

- Amanda Fischer, “Did the Paycheck Protection Program work for small businesses across the United States?” Washington Center for Equitable Growth, July 15, 2020, https://equitablegrowth.org/did-the-paycheck-protection-program-work-for-small-businesses-across-the-united-states/.

- Washington Center for Equitable Growth, “Factsheet: New study shows that emergency paid sick leave reduced COVID-19 infections in the United States,” October 26, 2020, https://equitablegrowth.org/factsheet-new-study-shows-that-emergency-paid-sick-leave-reduced-covid-19-infections-in-the-united-states/.

- Gregory Acs and Kevin Werner, “How a Permanent Expansion of the Child Tax Credit Could Affect Poverty,” Urban Institute, July 29, 2021, https://www.urban.org/research/publication/how-permanent-expansion-child-tax-credit-could-affect-poverty.

- Zachary Parolin, Elizabeth Ananat, Sophie M. Collyer, Megan Curran and Christopher Wimer, “The Initial Effects of the Expanded Child Tax Credit on Material Hardship,” National Bureau of Economic Research, September 2021, https://www.nber.org/papers/w29285.

- Bryce Covert, “The American Rescue Plan’s Child Care Test Run,” The American Prospect, April 11, 2022, https://prospect.org/health/american-rescue-plans-child-care-test-run/

- Sarah Jane Glynn and Diana Boesch, “Bearing the Cost: How Overrepresentation In Undervalued Jobs Disadvantaged Women During the Pandemic,” U.S. Department of Labor, March 15, 2022, https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/WB/media/BearingTheCostReport.pdf.

- The White House, “President Biden’s Bipartisan Infrastructure Law,” Accessed May 20, 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/bipartisan-infrastructure-law/.