Maryland is one of the most diverse states in the nation,1 with a pre-K–12 school system that serves nearly a million students and employs over 60,000 teachers.2 Yet while Maryland’s student population is increasingly diverse, the state’s public schools remain highly segregated—both within and across its twenty-four districts. This racial segregation in education is accompanied by a lack of diversity in Maryland’s teaching workforce.

As of 2022, over 70 percent of teachers in Maryland are white, whereas less than 40 percent of its student population is white.3 Comparatively, 18.8 percent of Maryland’s teachers are Black, compared to 33.2 percent of its students; and only 4.2 percent of the state’s teachers are Hispanic/Latino, compared to 21 percent of its students. This lack of diversity among educators works to deepen existing opportunity gaps, experienced disproportionately by low-income communities of color. Research shows that increased teacher diversity fosters cultural competency across faculty, improves students’ academic achievement and self-perception, and increases the likelihood of college enrollment.4 In school systems that lack diversity among educators, such benefits are withheld largely from students of color who, even when composing the majority of the school population, are less likely to see them represented in the classroom or in school leadership.5

Fortunately, Maryland has paid growing attention to the need for workforce diversification in recent years.6 In 2021, the state passed The Blueprint for Maryland’s Future, a bill that intends to transform its education infrastructure, including improving the quality and diversity of teachers entering schools.7

Educator preparation programs (EPPs) are pivotal actors in the state’s efforts to strengthen its educator workforce. EPPs, also referred to as teacher preparation programs (TPPs), are designed to help undergraduate and graduate students gain their professional teaching license. EPPs range in duration from two years (typically alternative programs for degree holders) to four to five years (for undergraduate and/or dual master’s degree programs).

Unfortunately, over the past decade, enrollment in Maryland’s EPPs has decreased by a third, and completion rates have declined by almost the same amount.8 Continuing drops in EPP enrollment and completion contribute to a growing number of teaching vacancies, exacerbate inequity felt most acutely by schools serving low-income students of color, and intensify disparities in teacher diversity, as fewer candidate teachers of color enter or complete their programs.9

Nevertheless, change is afoot. Maryland’s school districts are beginning to take much needed action not only to increase the presence of qualified teachers that match the diversity of their students, but also to support them as they engage with their students. While numerous actions are being taken across the state, this report focuses primarily on the role of school districts and EPPs in promoting workforce diversity.10 These institutions are well-positioned to transform the quality of teachers and culture of teaching as the sites where teachers build their professional foundation.

This report looks at Maryland’s approaches to creating an inclusive, integrated teaching workforce in order to derive lessons for other states and school districts. First, the report explores historical and legislative precedent in Maryland to paint the landscape that state school districts and EPPs operate within. Next, the report discusses three actions to advance workforce diversity and teacher supports, using examples from district-level initiatives across Maryland. Lastly, the report outlines the costs of insufficient teacher diversity as a caution to districts that do not adequately pursue and support diversity among their teaching workforce.

A History of Teacher Segregation and Displacement

To understand how and why Maryland’s teacher workforce failed to diversify along with its student population, it’s necessary to retrace how legislation and public policy eliminated many teachers of color from the workforce, and—along with other factors, such as economic and cultural trends and barriers—has kept them out.

The curious thing is, Maryland used to have a significant number of teachers of color. Over a century ago, educators like Emma L. Grason Miller taught with passionate vigor and an intense understanding of education’s value, particularly for Black students.11 Raised in Baltimore before moving to Chestertown, Miller established a school to educate Kent County’s Black youth. In 1911, the Hampton Institute graduate would go on to become the county’s first supervisor of “colored” schools while motivating her community to see the need for improved education beyond the sixth grade standard. Her efforts were crucial to the construction of the first “colored” high school, Henry Highland Garnet School, in 1916.12 Countless Black educators like Miller prioritized the growth of their communities during segregation and, despite immense challenges, persevered to bring transformative education to many.

Decades before the U.S. Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education declared state-sanctioned segregation unconstitutional in 1954, Maryland and nine other dual-system states offered tuition scholarships for Black students to attend out-of-state universities. In 1937, the Maryland Commission on Scholarships for Negroes was created.13 The state allotted $220,000 (equivalent to $3.7 million today) over the course of more than two decades “for the purpose of securing for such negros, without additional cost, educational facilities equal to those afforded White students.”14

Black graduate students who could not find desired coursework at colleges that accepted Black applicants, such as Morgan State or Prince Anne (now, University of Maryland Eastern Shore)—despite said coursework being offered at the University of Maryland, a segregated university—used their scholarships to earn professional degrees at top-ranked universities such as Columbia University, the University of Chicago, and Harvard University. Many earned their credentials and returned home to be principals and teachers at all-Black schools. Well-respected and highly qualified, generations of Black educators empowered their students and communities in Maryland through fierce leadership and a devout commitment to education excellence.

While the Brown decision was a win for desegregationists as it outlawed explicit racial segregation in schools, there were some negative consequences. One was that the Black educator workforce was decimated by the closure of all-Black schools, as well as by racially discriminatory firings and demotions. Had Emma L. Grason Miller, who passed in 1951, lived to see Brown’s ruling implemented, she may have been one of the nation’s 38,000 Black teachers forced out of the profession she dedicated her life to.15

Throughout the mid- to late-twentieth century, school integration nationwide was intentionally undermined through racist policy and violence toward Black and Hispanic communities. For instance, four months after the Baltimore School Board unanimously voted to end school segregation in June 1964, ten Black students at Southern High School (now Digital Harbor High School) faced an estimated 500 rioters calling for an end to integration.16 Epithets from white protesters outside occurred in tandem with racism from white school staff.17 Similar violence occurred at Gwynns Falls Park Junior High School, with police only responding after a Black parent, Clarence Mitchell, began a one-man counter protest.18

Even more, numerous all-Black schools were closed following the Brown decision, leading to a reorganization of Black educators. For instance, in 1955, Montgomery County announced a closure of four “substandard” all-Black schools, reassigning teachers and administrators to twelve previously all-white schools.19 In certain districts, like Harford County, Black educators were told they had to return to school to learn how to teach white students.20 Erroneous perceptions of Black inferiority further fueled massive resistance from white parents and district administrators, which greatly hindered efforts to hire Black educators, let alone educators of other races. Though Black educators throughout the state organized rigorously to end workplace discrimination, the slow pace of district action limited the potential to curtail teacher displacement and discrimination.

Today, teacher displacement in Maryland can appear less explicit, but it remains devastating to the composition of the workforce. Barriers to the profession are embedded within entrance criteria, standardized certification exams, and constrained financial aid opportunities.21 Research finds Black and Hispanic teacher candidates perform disproportionately worse than their white peers on licensure exams.22 Every retake incurs an additional cost to candidates of color—who are also more likely to not retake the exam after failing the first time.23 The additional salary disparity for teachers—84 cents on the dollar in Maryland—only further disincentives entry to the profession.24 Taken together, history brings us to a place where fewer people of color can afford to become teachers, even if they feel called to serve in schools.

Almost every region in the United States is struggling with improving teacher diversity. To progress toward integration, policymakers should consider how they would define a representative workforce, and how that definition should influence policy priorities.

How Diversity Is Measured Matters

Teacher diversity can be measured in numerous ways.25 Most commonly, the difference between the share of teachers and the share of students for a given racial/ethnic group are measured and expressed as a teacher–student diversity gap. While helpful to a certain extent, gap measures are not as useful when comparing diversity across localities.

For instance, let’s say there are two districts. In District A, 0 percent of teachers are Hispanic and 20 percent of students are Hispanic, while in District B, 60 percent of teachers are Hispanic and 80 percent of students are Hispanic. In this scenario, both districts would have a diversity gap of 20 percentage points, signaling they have a similar lack of diversity—but in reality, District A arguably has a far more serious problem than District B.

To capture diversity and its absence more accurately, districts can use the Teacher–Student Parity Index, which divides the percentage of teachers for a given racial identity by the percentage of students with that same identity.26 A group with perfect parity has an index of 1, meaning there is an equal proportion of teachers and students of a given racial/ethnic background. If the index is greater than 1, teachers of a given group are overrepresented relative to the proportion of students of the same group. If the index is below 1, said teachers are underrepresented relative to said students.

Returning to the example above, District A has a Hispanic Teacher–Student Parity Index of 0.0 while District B has an Index of 0.75. Through this measurement, we can determine that District A is much farther from parity and has a more urgent need to recruit teachers than District B to have a representative workforce relative to the student population.

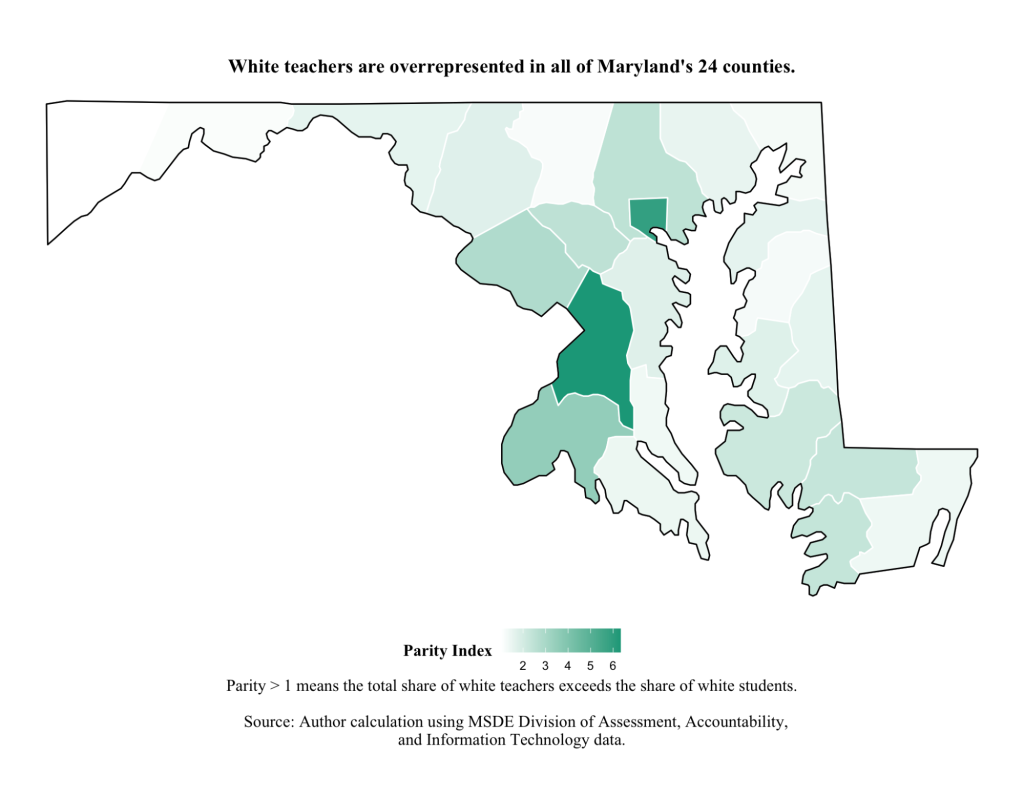

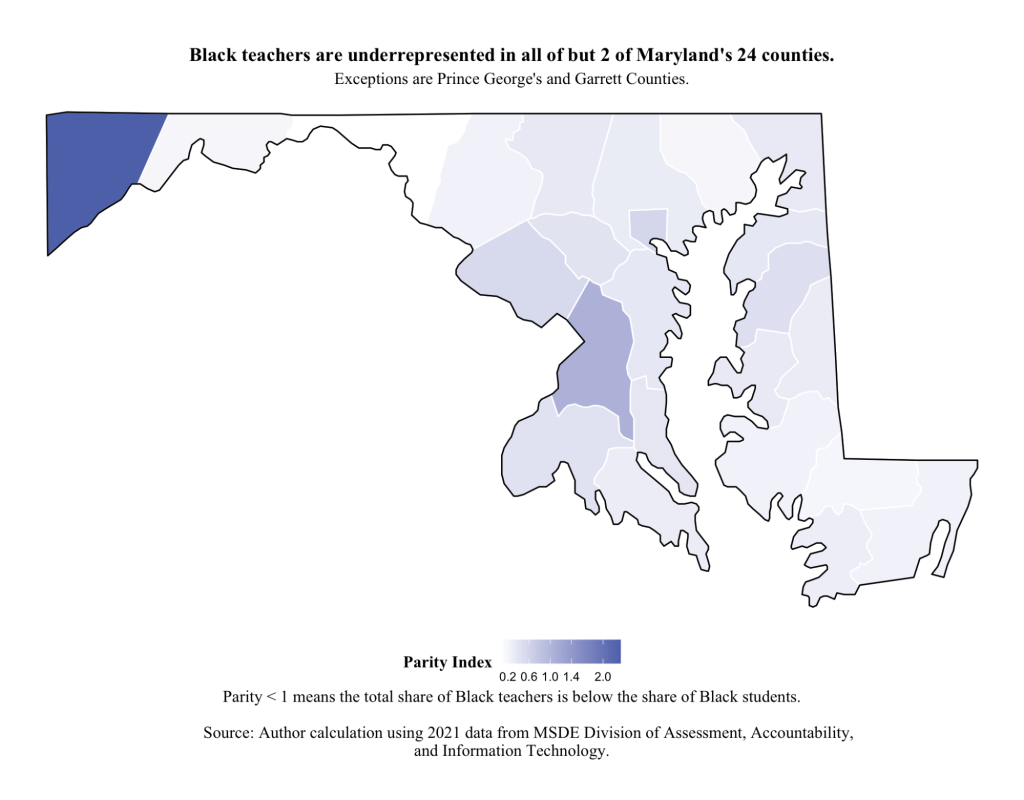

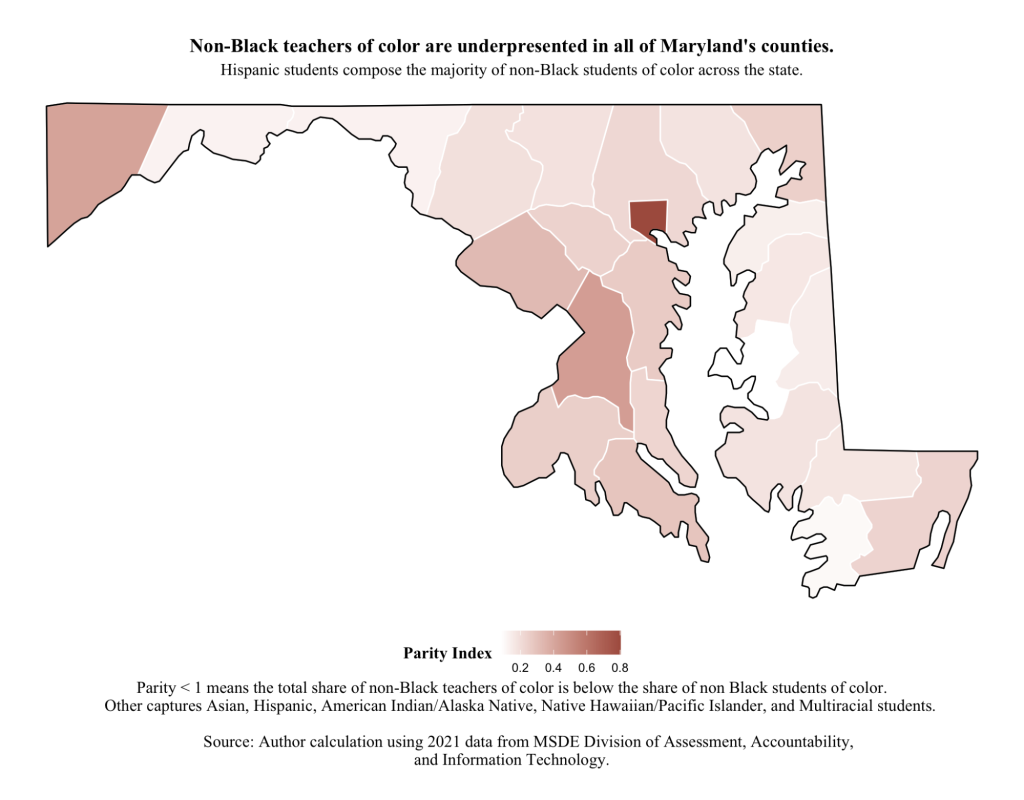

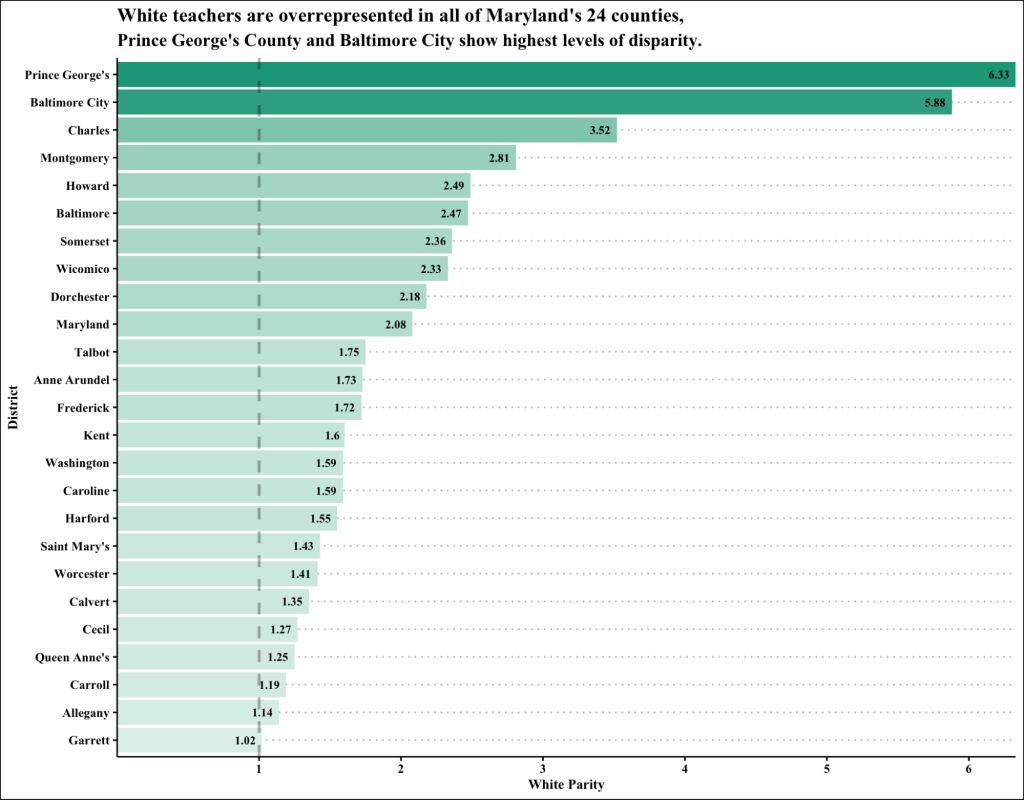

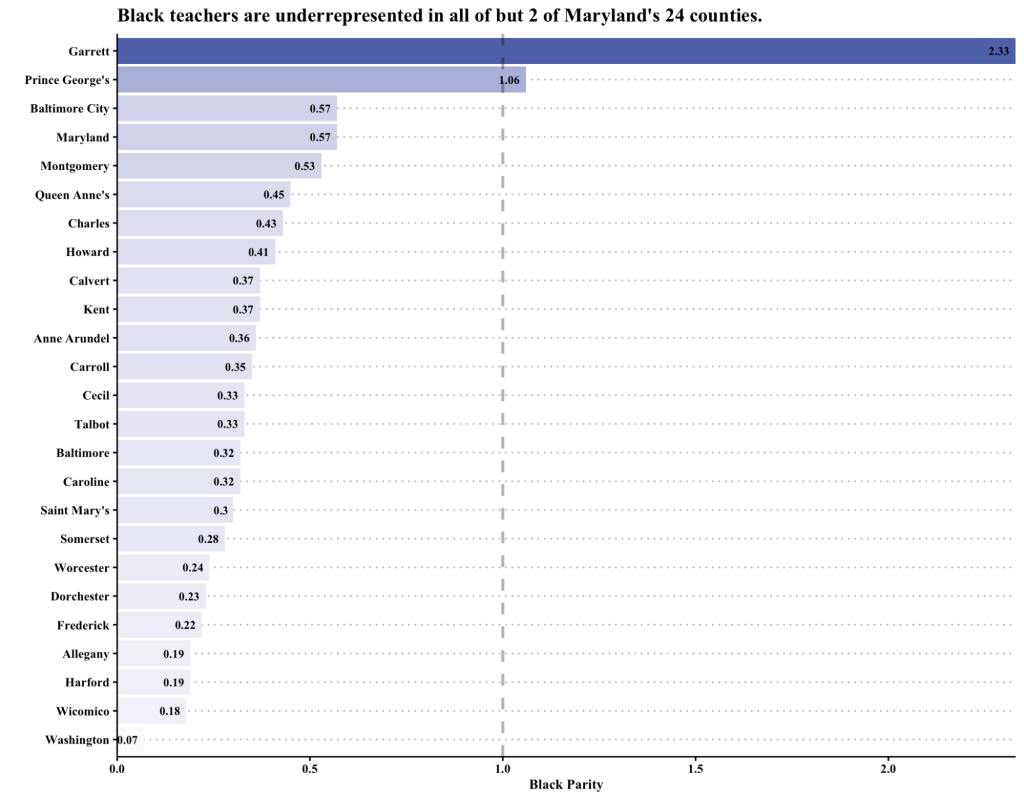

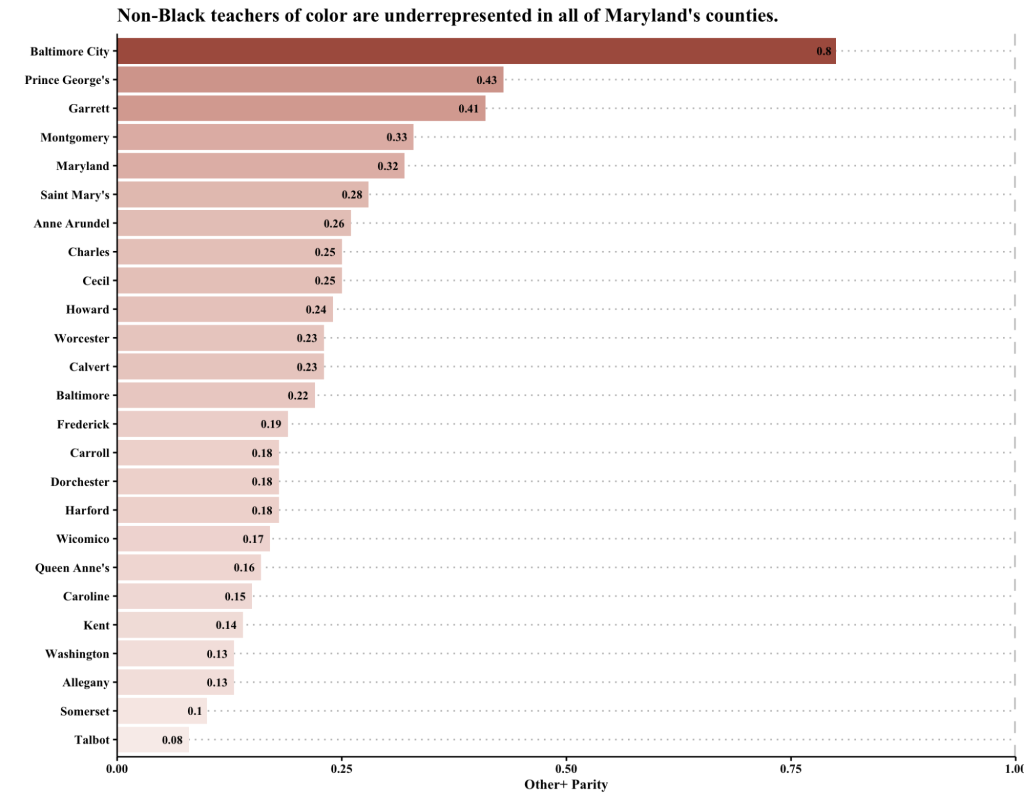

In examining Maryland, the research for this report finds that white teachers are overrepresented relative to white students in all twenty-four counties (see Figure 1). Black teachers are underrepresented in all but two counties (Prince George’s and Garrett County; see Figure 2). Analysis for teachers of other racial/ethnic groups in the state is difficult, because the state data groups all such teachers into the “Other +” category. This categorization makes it challenging to accurately capture statewide differences in diversity for any of these identities. Nevertheless, analysis using this “Other +” designation alone signals that Maryland’s workforce diversity for these teacher groups has not kept up to pace with student diversity.

Figure 1: White Teahcer–Student Parity Index

Figure 2: Black Teacher–Student Parity Index

Figure 3: Other+ Teacher–Student Parity Index

It is worth noting that achieving demographic parity alone does not translate to meaningful integration. If districts are to avoid replicating historic harms, districts should make deliberate investments not only in achieving diversity of teachers entering the workforce, but also in transforming the quality of their preparation. Thankfully, Maryland has begun this transformation through its recent landmark legislation, The Blueprint for Maryland’s Future.

Maryland’s Blueprint to Foster and Sustain Teacher Diversity

In 2021, Maryland passed House Bill 1300, The Blueprint for Maryland’s Future (The Blueprint). This legislation included substantial initiatives intended to improve the quality of the state’s education system. The Blueprint is organized around five “pillars,” the second of which is intended to create a high quality, diverse workforce.27

To achieve this aim, the Blueprint included a nearly $48 million investment in “Grow Your Own Staff” grants allowing districts to develop pathways to teaching, such as residencies and apprenticeships.28 This funding was awarded as single, noncompetitive grants. Through this bill, Maryland and its districts espoused a commitment to recruiting and preparing a more diverse teaching force.

The Blueprint calls for, among other objectives, altering and enhancing requirements for teacher training practicums and preparation programs. These statutes aim to elevate the state’s education system and attract more high-quality teachers from various backgrounds. EPPs are crucial partners in achieving this goal, as §1-303(2)(ii) of Maryland’s education code now outlines:29

Teacher preparation programs in the State’s postsecondary institutions that are rigorous and prepare teacher candidates to have the knowledge, skills, and competencies needed to improve student performance and to teach all students successfully regardless of the student’s economic background, race, ethnicity, and learning ability or disability.

Before the Blueprint, in 2019, the state addressed some barriers to EPP enrollment by amending its certification requirements. In lieu of a basic skills assessment, candidates could be admitted if they have a 3.0 GPA. This policy change initially only applied to candidates enrolling in traditional EPPs (that is, undergraduate students) operated by local universities and colleges. However, as of July 2022, the policy has expanded to candidates seeking Resident Teacher Certificates. Said candidates are typically degree-holders seeking licensure. The examination criteria remains in place for conditionally certified teachers (who are disproportionately Black), but the state did approve a renewal extension, allowing these teachers to renew their certification more than once.

Almost all enrollees in traditional EPPs use the GPA pathway, and this innovation has increased program enrollment. In comparison, alternative EPPs, which required enrollees to pass the basic skills assessment, lost 23 percent of their Black candidates during the 2019–20 academic year.30 Whether the expansion of the examination waiver to alternative EPPs will increase resident teachers similar to traditional EPP enrollment remains to be seen.

The above policy changes illustrate promising efforts to fill staff vacancies and increase access to high-quality, rigorous teaching training. However, they do not address the significant barriers hindering Maryland’s over 300 EPPs from supporting their candidates, particularly those of color, beyond enrollment to certification and licensure.

Addressing the educator diversity disparity in Maryland—as in the rest of the nation—requires multi-pronged initiatives that meet candidate educators of color where they are. For EPP programs to become rigorous, diverse institutions that fulfill the Blueprint’s aims, their models must embed supports that are responsive to the unique challenges faced by marginalized candidate teachers. To this end, this report will now explore how Maryland’s school districts and EPP providers are approaching the call to improve teacher diversity without compromising on training quality.

Lessons for School Districts and Educator Preparation Program Providers

This section explores three actions that localities can take (and many are taking) to shift greater support in service of workforce diversification. Pulled from efforts of districts in Maryland and current literature on effective pathways to increase college completion, EPP quality, and teacher (self-) efficacy, these lessons chart potential courses to greater diversity and education equity.

Commit to Explicit Diverse Recruitment and Completion Goals

Virtually every school district received a Grow Your Own Staff grant under the Maryland Leads grant initiative.31 A wide range of activities are approved under the grant, including expanding resident teacher programs, supporting teacher recruitment task forces, and providing tuition-free licensure coursework for teachers entering hard-to-staff disciplines. These initiatives were intended by their districts to deliver a range of expected impacts that reflect districts’ varying workforce development priorities. Of these impacts, fewer than 40 percent of Maryland’s districts set clear goals to increase staff diversity.

Because all twenty-four of Maryland’s districts lack adequate diversity, to actualize and maintain diversity, districts must work toward progressive benchmarks. Montgomery County, for instance, intends to increase the number of teachers of color by 3 percent over the next five years.32 As of 2021, 29 percent of the county’s teachers are non-white, whereas 75 percent of its students are those of color. Montgomery is the largest county in Maryland, with a sizable pool of potential teachers from diverse backgrounds. Yet its low target for increasing teacher diversity doesn’t take advantage of this pool and likely won’t bring significant changes to teacher–student parity.

Smaller school districts with high percentages of white teachers, such as Calvert County Public Schools, have set ambitious goals.33 Calvert, whose non-white teacher population was less than 10 percent in 2021, hoped to see a 50 percent increase in the diversity of its teaching staff by June 2023. Worcester County, whose non-white teacher population stood at 8.3 percent, plans to see a 20 percent increase in the number of teachers of color entering school administration by 2024.34 Though not as ambitious as Calvert’s, Worcester’s goal places necessary attention on the lack of diversity in school administration specifically. District-tailored approaches are crucial as each of Maryland’s districts is at a different stage in its educator integration journey. However, regardless of district size or stage, ambitious, time-bound goals and thoughtful planning are important because they increase the likelihood for accountability and deliberate resource allocation in service of workforce integration.

Nonetheless, for any of these districts’ actions to have their anticipated impact, EPPs must be ready to support an influx of teacher candidates from their entry all the way through graduation to certification. Fortunately, EPP providers will receive help on this front through the Maryland Educator Shortage Reduction Act of 2023, approved by Governor Wes Moore in May.35

The act, amongst other things, provides technical assistance to EPPs to seek and retain “highly qualified individuals, including individuals from groups historically underrepresented in the teaching profession.” It also provides teacher internship stipends and prioritizes publicizing scholarship availability to historically Black colleges and universities, students from underrepresented backgrounds, and support staff in public schools.

Even more, the act calls for EPPs to establish specific recruitment and retention goals, with the Maryland State Department of Education set to create an “Educator Recruitment, Retention, and Diversity Dashboard” by January 2025. A well-designed dashboard can create necessary transparency and provide accessible metrics about progress toward diversity. More critically, a dashboard enables policymakers and community members to identify schools most profoundly affected by scant teacher diversity. Thoughtful analytics should disaggregate racial data (that is, the “Other +” categorization) and could incorporate other markers of diversity like gender identity, sexual orientation, and bi-/multilingualism. As districts develop a deeper understanding of their levels of diversity, they become better equipped to allocate resources to teacher and teacher candidates with the greatest potential and/or need.

Notably, the act was amended to stop the creation of a statewide Grow Your Own Educator Scholarship Program, opting instead for a Teacher Development and Retention Fund for candidates who commit to serving in a high-needs school, grade-level, or content area. Calls for districts to grow their own educators are part of a growing trend for localized responses to address workforce vacancies and teacher quality. While a standalone, statewide Grow Your Own program does not yet exist in Maryland, many districts offer programs that embody the approach’s philosophy.

Grow Your Own Teachers, Regardless of EPP Pathway

Maryland offers over 300 traditional EPPs across twenty-three of its institutions of higher education (IHEs) and nine alternative EPPs. Traditional programs offer undergraduate (or joint-graduate) degrees in education across a variety of subjects. Alternative programs are typically one-year or two-year programs for individuals who already have a degree. Some are nationally known, such as Teach for America, while others are local residencies, such as the Alternative Certification for Effective Teachers (ACET) program in Montgomery County or the Maryland Accelerates program offered by Frostburg State University.36 Both pathways have faced declining enrollment and completion over the past decade, further exacerbating workforce diversity disparities and staff shortages.

It can be desirable to create a dichotomy between the value of traditional and alternative preparation programs in improving workforce diversity. However, to do so oversimplifies the nuanced circumstances and program models shaping the choices of teacher candidates. For instance, a “traditional” candidate may earn a bachelor’s degree (or minor) in education then pursue a two-year residency before committing to a teaching career. Or, an “alternative” candidate may desire to study a non-education-related discipline as an undergraduate before pursuing a one-year graduate teaching degree. Neither of these pathways should be valued more highly over the other. Furthermore, traditional and alternative EPPs are peer institutions who could learn a great deal by sharing strategies and positive system changes.

Although alternative EPPs are often more diverse than their traditional counterparts, there are not enough alternative programs to fill Maryland’s staffing vacancies. In 2021, only 15 percent of certificate eligible program completers were from alternative programs.37 Most teachers go the traditional route. Supporting this pathway by making traditional programs more accessible through robust financial support could also promote workforce diversity by ensuring that districts have a viable pathway for all interested candidates.

Rather than push a particular pathway, Maryland gives its districts’ autonomy to develop EPPs that best meet local needs, following the philosophy of Grow Your Own (GYO) programs. GYOs began as equity-centered initiatives to remove traditional entry barriers for candidate educators of color, particularly in urban communities.38 Their intent was to recruit students directly from the local community or staff currently in schools who can be trained as teachers. GYO teacher initiatives have risen in popularity, with organizations like New America providing insightful information on how to design, develop, and implement strong programs.39

Paraprofessionals (instructional aids, long-term substitutes) are well-positioned to benefit from GYO programs. Research finds paraprofessionals prepared through GYO programs have higher retention rates compared with teachers from traditional EPPs.40 Maryland’s paraprofessional workforce is slightly more diverse than its teaching workforce, suggesting a pool of diverse, dedicated teachers is currently waiting to be identified internally. Several districts have articulated plans to support licensure of current paraprofessionals, such as Somerset County’s Para-To-Teacher program and Wicomico County’s plan to provide tuition assistance and mentoring to paraprofessionals.41

Other GYOs target high school students with the hopes of motivating them to pursue education degrees in college. The Teacher Academy of Maryland (TAM), for instance, is a Career and Technology Education (CTE) program developed by Towson University in collaboration with the Maryland State Department of Education and the University System of Maryland.42 Students who successfully complete coursework between tenth and twelfth grade with a cumulative GPA of 3.0 and program portfolio are eligible to receive college credit and scholarships from a variety of institutions. In Maryland, counties such as Calvert, Dorchester, and Talbot are using their GYO Staff grant to recruit and provide financial aid to TAM students.43 Such efforts provide prospective teachers with a learning community, financial resources, and an accessible route to teach in their local area.

Whether districts recruit paraprofessionals, high schoolers, or career-changers, preparation programs should be designed to improve candidate teachers’ self-efficacy, strengthen their pedagogy, and prepare them to succeed on necessary certification exams. Close attention should be paid to the alignment between the daily work of teachers and curriculum taught to candidate teachers. Through greater alignment and professional support, EPP providers and districts give candidates their best shot at thriving as a teacher.

Provide Comprehensive, Teacher-Candidate-Centered Mentoring

Strong mentorship of new teachers by experienced licensed teachers is easy to take for granted, which makes it particularly precious. Research consistently reports that the strength of mentoring relationships and induction supports plays a critical role in retaining new teachers.44 Effective mentorship can foster a deep relationality that strengthens new teachers’ perception of their self-efficacy and belonging in the education workforce, increasing their likelihood of staying in the profession.

Following this logic, advising teacher candidates on the realities of their job is particularly important, especially as they start to balance coursework and certification prep with classroom responsibilities. Experimental research finds intensive advising can significantly increase students’ likelihood of earning their bachelor’s degree.45 While traditional advising models are usually in-person, virtual advising programs also offer retention and teacher self-efficacy benefits. Studies find positive effects of virtual advising with preservice music teachers and first-term preservice teachers.46 In either format, allocating resources to quality mentors programs for teacher candidates can be an effective first step to building a sustainable teaching pipeline.

For teachers of color specifically, their identities are often central to their teaching pedagogies, influencing not only their student–family interactions but also their relationships with colleagues. As such, connecting teacher candidates of color with experienced teachers of color who provide pedagogical and institutional know-how on a consistent basis can increase a candidate’s capacity to successfully navigate their coursework, job responsibilities, and professional goals.

In Maryland, the Building Our Network of Diversity (BOND) Project seeks to foster this precise kind of connection.47 The BOND Project is an initiative from Montgomery County Public Schools committed to advancing the recruitment, development, retention, and empowerment of male educators of color. The organization offers a series of programs, including the BOND Learning and Leadership Institute for Boys, which offers mentorship and fellowship to male students in fourth through twelfth grades.48 Male students of color get the opportunity to learn from men currently working in classrooms, opening their eyes to education as a viable career path.

Mentorship is already a required component of comprehensive induction programs in Maryland districts.49 Similar prioritization of thorough mentorship should be embedded within EPPs to lower the risk of candidates’ exiting the profession before they are even certified. Conversely, strong mentorship can help candidate teachers determine if teaching is the right profession for them and lower the odds of undedicated individuals entering classrooms.

At its core, education is a profession that thrives on collegiality and collaboration. When districts are proactive in fostering these healthy dynamics between their teacher candidates and teachers of record, they can reap the benefits of a workforce that feels well-supported and welcoming to all.

The Costs of Undervaluing Teacher Diversity and Integration

Students and teachers of color often shoulder the brunt of educational inequity. Nationwide, students and teachers of color are disproportionately concentrated in underinvested schools and districts that are racially and economically isolated.50 Black and Hispanic teachers are more likely to work in schools that serve higher populations of Black and Hispanic students. These schools often operate within segregated metropolitan districts with higher concentrations of impoverished families. Despite these metro areas having a more diverse teaching workforce relative to their suburban or rural counterparts, white teachers still compose over two-thirds of the workforce—particularly, white women.

Actively creating a more representative teaching workforce is vital to advancing educational equity. Students with greater exposure to same-race teachers benefit from a safer learning environment where they are less likely to be suspended, more likely to graduate, and have greater access to role models with an intimate knowledge of their culture.51 Reimagining the teaching profession to center diversity can further expand this access and save districts’ vital resources as their teachers feel better supported to meet the diverse needs of their students and their personal goals.

Greater diversity and integration in the teaching workforce saves districts money. District expenditures on separation, recruitment, hiring, and training are estimated to cost between $9,000 and $21,000 per teacher nationwide, depending on district size and student demographics (such as share of free/reduced price lunch eligible students).52 During the 2021–22 academic year, Maryland had over 1,600 teacher vacancies and statewide attrition stood at 10 percent. The state spends millions of additional dollars attempting to fill these gaps in human capital. This is funding that could otherwise go toward education innovations such as infrastructural improvements or updated curricular materials.53

Considering the complexity of workforce integration, not all costs are quantifiable. Teachers of color, particularly those early in their careers, can get caught in a double bind where they must navigate oppressive, racist hierarchies in schools that conflict with their personal commitments, whether it is a commitment to values like educational justice or practices like engaged pedagogy.54 The costs of restructuring this exclusionary system are as physical and psychological as they are fiscal. Accounting for these phenomena won’t fit neatly in a cost–benefit analysis, but acknowledging their impact greatly affects whether teachers of color feel their labor is seen, respected, and valued.

Looking Ahead

In brief, to revitalize teaching, districts will need to diversify their teacher workforce. In the past three decades, America has made slow growth in improving the racial composition of the teacher workforce. Maryland’s districts are making promising movements to accelerate the pace of this growth. Although results of the efforts shared in this report are still in the making, it is the increased investment in workforce diversity and development that signal positive change.

Regardless of the state, creating inclusive schools that recruit and retain high-quality teachers of color requires districts to reject tokenism in favor of integration, and foster consciousness about the value of diverse educators. This process should begin in educator preparation programs but should continue throughout all stages of a teacher’s career. If teachers are to give their all for their students well-being, then districts and EPP providers must give their all to ensure teachers’ well-being.

It should go without saying that every child deserves a teacher who carries compassion for their identities and is well-equipped to meet their educational needs. Just the same, every teacher deserves respect and abundant support to meet their professional needs. Neither of these realities will come to fruition across Maryland—let alone the nation—without intentional efforts to transform the quality and diversity of the educator workforce.

Notes

- A. McCann, “Most and Least Diverse States in America,” WalletHub, 2021, https://wallethub.com/edu/most-least-diverse-states-in-america/38262.

- “Teachers & Certificated Staff,” Maryland State Education Association, 2020, https://marylandeducators.org/about-msea/teachers/.

- M. Choudhury, “MSDE Updates and Maryland’s Teacher Workforce: Supply, Demand, and Diversity,” Maryland State Department of Education, August 25, 2022, https://mgaleg.maryland.gov/meeting_material/2022/aib%20-%20133059203701707978%20-%20AIB%20Presentation%208.25.22.pdf.

- A. J. Egalite, B. Kisida, and M.A. Winters, “Representation in the classroom: The effect of own-race teachers on student achievement,” Economics of Education Review 45 (2015): 44–52, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2015.01.007.

- “Race and Ethnicity of Public School Teachers and Their Students,” National Center for Education Statistics, 2020, https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2020/2020103/index.asp.

- M. Choudhury, “Maryland’s Teacher Workforce: Supply, Demand, and Diversity,” Maryland State Department of Education, July 26, 2022, https://www.marylandpublicschools.org/stateboard/Documents/2022/0726/TabGBlueprintAndDataDeepDiveTeacherPipelineAndDiversity.pdf.

- “Blueprint for Maryland’s Future,” Maryland State Department of Education, https://blueprint.marylandpublicschools.org/.

- M. Choudhury, “Maryland’s Teacher Workforce: Supply, Demand, and Diversity,” Maryland State Department of Education, July 26, 2022, https://www.marylandpublicschools.org/stateboard/Documents/2022/0726/TabGBlueprintAndDataDeepDiveTeacherPipelineAndDiversity.pdf.

- K. deCourcy, “High and rising teacher vacancies coincide with a steep decline in the overall well-being of the teaching profession,” Economic Policy Institute, March 10, 2023, https://www.epi.org/blog/high-and-rising-teacher-vacancies-coincide-with-a-steep-decline-in-the-overall-well-being-of-the-teaching-profession/.

- Much of this report is an adaptation of the author’s graduate policy capstone on Maryland’s teacher diversity disparity.

- J. Dissette, “Mid-Shore History: The Hidden Truth of Emma L. Grason Miller with Karen Somerville,” The Chestertown Spy, August 8, 2022, https://chestertownspy.org/2022/08/08/mid-shore-history-the-hidden-truth-of-emma-l-grason-miller-with-karen-somerville/.

- J. Dissette, “H. H. Garnet School Honors Black Educator Emma L. Grason Miller,” The Chestertown Spy, December 19, 2022, https://chestertownspy.org/2022/12/19/h-h-garnet-school-honors-black-educator-emma-l-grason-miller/

- L. T. Fenwick, Jim Crow’s Pink Slip: The Untold Story of Black Principal and Teacher Leadership (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Education Press, 2022).

- “Session Laws, 1937,” Maryland State Archives, https://msa.maryland.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc2900/sc2908/000001/000412/html/am412–1071.html.

- J. Owens and J. Muñiz, “It’s Time to Right Historical Wrongs by Investing in Black Teachers,” New America, December 14, 2020, https://www.newamerica.org/education-policy/edcentral/its-time-to-right-historical-wrongs-by-investing-in-black-teachers/.

- R. Fields, “Brown vs. Board of Education: 50 Years Later,” Baltimore Sun, May 16, 2004, https://www.baltimoresun.com/news/bs-xpm-2004-05-16-0405140133-story.html.

- A. McDaniels, “When my mother-in-law helped desegregate Southern High School,” Baltimore Sun, September 10, 2020, https://www.baltimoresun.com/opinion/op-ed/bs-ed-op-0911-mother-in-law-desegregated-southern-high-school-20200910-4yiud62vanc4djh6elleokwg4y-story.html.

- Lee Sartain, Borders of Equality: The NAACP and the Baltimore Civil Rights Struggle, 1914–1970 (Jackson, Miss.: University of Mississippi Press, 2013.

- “Statement of C. Taylor Whittier, Superintendent of Schools, Montgomery County, MD,” Conference before the United States Commission on Civil Rights, March 21–22, 1960.

- “Shirley Rose: African American Teachers Deal With Official Racism,” Harford Civil Rights Project, 2016, https://harfordcivilrights.org/files/show/140.

- C. W. Case, R. J. Shive, K. Ingebretson, and V. M. Spiegel, “Minority Teacher Education: Recruitment and Retention Methods,” Journal of Teacher Education 39, no. 4 (1988): 54–57, https://doi.org/10.1177/002248718803900410; J. Torres, J. Santos, N. Peck, and L. Cortes, “Minority Teacher Recruitment, Development, and Retention,” The Education Alliance at Brown University, 2004, https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED484676.pdf.

- A. Cuenca, “Mis-Shaping The Teaching Force: An Analysis of Passing Rates of Indiana’s Teacher Candidates,” 2022, https://ceep.indiana.edu/education-policy/policy-reports/2022/ceep-report-22.a-mis-shaping-the-teaching-force.pdf

- “Driven by Data: Using Licensure Tests to Build a Strong, Diverse Teacher Workforce,” National Council on Teacher Quality, July 2021, https://www.nctq.org/publications/Driven-by-Data:-Using-Licensure-Tests-to-Build-a-Strong

- “Salaries,” Maryland State Education Association, https://marylandeducators.org/career-resources/salaries/.

- M. Hansen and D. Quintero, “4 ways to measure diversity among public school teachers,” Brookings Institution, November 17, 2017, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/brown-center-chalkboard/2017/11/17/four-ways-to-measure-diversity-among-public-school-teachers/.

- Ana Maria Villegas, Kathryn Strom, and Tamara Lucas, “Closing the Racial/Ethnic Gap Between Students of Color and Their Teachers: An Elusive Goal,” Equity and Excellence in Education 45, no. 2 (2012): 283–301, https://doi.org/10.1080/10665684.2012.656541.

- “Blueprint Pillar 2: High Quality and Diverse Teachers and Leaders,” Maryland State Department of Education, https://blueprint.marylandpublicschools.org/hqdtl/.

- “MSDE Awards More Than $169 Million to Local Education Agencies as Part of Maryland Leads Grant Program,” Maryland State Department of Education, June 28, 2022, https://news.maryland.gov/msde/msde-awards-more-than-169-million-to-local-education-agencies-as-part-of-maryland-leads-grant-program/.

- Blueprint for Maryland’s Future—Implementation, MD. Stat. §1-303 (2020), https://mgaleg.maryland.gov/2020RS/bills/hb/hb1300f.pdf.

- M. Choudhury, “Maryland’s Teacher Workforce: Supply, Demand, and Diversity,” Maryland State Department of Education, July 26, 2022, https://www.marylandpublicschools.org/stateboard/Documents/2022/0726/TabGBlueprintAndDataDeepDiveTeacherPipelineAndDiversity.pdf.

- “The Maryland Leads Initiative,” Maryland State Department of Education, https://marylandpublicschools.org/about/Pages/MDLeads/index.aspx.

- “Maryland Leads LEA Summary—Montgomery County,” Maryland State Department of Education, 2022, https://marylandpublicschools.org/about/Documents/MDLeads/Montgomery%20County.pdf.

- “Maryland Leads LEA Summary—Calvert County,” Maryland State Department of Education, 2022, https://marylandpublicschools.org/about/Documents/MDLeads/Calvert%20County.pdf.

- “Maryland Leads LEA Summary—Worcester County,” Maryland State Department of Education, 2022, https://marylandpublicschools.org/about/Documents/MDLeads/Worcester%20County.pdf.

- Maryland Educator Shortage Reduction Act of 2023, MD. Stat. §627 (2023).

- “Alternative Certification for Effective Teachers (ACET),” Montgomery College, https://www.montgomerycollege.edu/academics/abeess/school-of-education/alternative-certification-effective-teachers.html; “Maryland Accelerates Program,” Frostburg State University, https://www.frostburg.edu/academics/colleges-and-departments/college-of-education/Maryland-Accelerates-Program/maryland-accelerates-program.php.

- M. Choudhury, “Maryland’s Teacher Workforce: Supply, Demand, and Diversity,” Maryland State Department of Education, July 26, 2022, https://www.marylandpublicschools.org/stateboard/Documents/2022/0726/TabGBlueprintAndDataDeepDiveTeacherPipelineAndDiversity.pdf.

- A. Valenzuela, “Grow Your Own Educator Programs: A Review of the Literature with an Emphasis on Equity-based Approaches Literature Review,” Intercultural Development Research Association, November 2017, https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED582731.pdf.

- “Grow Your Own Educators,” New America, https://www.newamerica.org/education-policy/grow-your-own-educators/.

- Conra D. Gist, Margarita Bianco, and Marvin Lynn, “Examining Grow Your Own Programs Across the Teacher Development Continuum: Mining Research on Teachers of Color and Nontraditional Educator Pipelines,” Journal of Teacher Education 70, no. 1 (2018): 13–25, https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487118787504.

- “Maryland Leads LEA Summary—Somerset County,” Maryland State Department of Education, 2022, https://marylandpublicschools.org/about/Documents/MDLeads/Somerset%20County.pdf; “Maryland Leads LEA Summary—Wicomico County,” Maryland State Department of Education, 2022, https://marylandpublicschools.org/about/Documents/MDLeads/Wicomico%20County.pdf.

- “Teacher Academy of Maryland,” Towson University, https://www.towson.edu/coe/centers/teacheracademy/.

- “Maryland Leads LEA Summary—Calvert County,” Maryland State Department of Education, 2022, https://marylandpublicschools.org/about/Documents/MDLeads/Calvert%20County.pdf; “Maryland Leads LEA Summary—Wicomico County,” Maryland State Department of Education, 2022, https://marylandpublicschools.org/about/Documents/MDLeads/Wicomico%20County.pdf.

- Richard M. Ingersoll and Michael Strong, “The Impact of Induction and Mentoring Programs for Beginning Teachers: A Critical Review of the Research,” Review of Educational Research 81, no. 2 (2011), 201–33, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23014368.

- Zach Sullivan, Benjamin L. Castleman, Gabrielle Lohner, Eric Bettinger, “College Advising at a National Scale: Experimental Evidence from the CollegePoint Initiative,” 2021, (EdWorkingPaper: 19-123), retrieved from Annenberg Institute at Brown University, https://doi.org/10.26300/s323-5g64.

- J. Reese, “An Exploration of Interactions between Virtual Mentors and Preservice Teachers,” Contributions to Music Education 42 (2017), 201–21, https://eric.ed.gov/?q=source%3a%22Contributions+to+Music+Education%22&ff1=eduPostsecondary+Education&ff2=subMusic+Teachers&id=EJ1141808; R. L. Cornu, “Peer mentoring: engaging pre‐service teachers in mentoring one another,” Mentoring and Tutoring: Partnership in Learning 13(3), (2005): 355–66, https://doi.org/10.1080/13611260500105592.

- “The Building Our Network of Diversity (BOND) Project,” Bond Educators, https://bondeducators.org/.

- “BOND Learning and Leadership Institute for Boys,” Bond Educators, https://bondeducators.org/bond-boys-leadership-institute/.

- Code of Maryland Regulations (COMAR)—Comprehensive Teacher Induction and Mentoring, Maryland State Department of Education, https://www.marylandpublicschools.org/about/Pages/DCAA/ProfessionalLearning/COMAR.aspx.

- K. Schaeffer, “America’s public school teachers are far less racially and ethnically diverse than their students,” Pew Research Center, December 10, 2021, https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2021/12/10/americas-public-school-teachers-are-far-less-racially-and-ethnically-diverse-than-their-students/.

- Matthew Shirrell, Travis J. Bristol, Tolani A. Britton, “The Effects of Student-Teacher Ethnoracial Matching on Exclusionary Discipline for Asian American, Black, and Latinx Students: Evidence From New York City,” Edworkingpapers.com, 2021, https://edworkingpapers.com/ai21-475; Seth Gershenson, Cassandra M. D. Hart, Joshua Hyman, Constance Lindsay, and Nicholas W. Papageorge, “The Long-Run Impacts of Same-Race Teachers,” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 25254, November 2018, Revised February 2021, https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w25254/w25254.pdf.

- “What’s the Cost of Teacher Turnover?” Learning Policy Institute, September 13, 2017, https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/product/the-cost-of-teacher-turnover.

- Suryani Dewa Ayu, Alejandra Vázquez Baur, and Jonathan Zabala, “How the U.S. Can Build More Equitable, Inclusive, and Welcoming Schools,” Next100, November 7, 2022, https://thenext100.org/how-the-u-s-can-build-more-equitable-inclusive-and-welcoming-schools/.

- Elizabeth Bettini, Christopher J. Cormier, Maalavika Ragunathan, and Kristabel Stark, “Navigating the Double Bind: A Systematic Literature Review of the Experiences of Novice Teachers of Color in K–12 Schools,” Review of Educational Research 92, no. 4 (2021), https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543211060873.