Executive Summary

This report, jointly authored by The Century Foundation, the National Employment Law Project, and Philadelphia Legal Assistance, presents the findings of an intensive study of state efforts to modernize their unemployment insurance (UI) benefit systems. This is the first report to detail how UI modernization has altered the customer experience. It offers lessons drawn from state modernization efforts and recommends user-friendly design and implementation methods to help states succeed in future projects.

While the need for better systems was apparent even before the COVID-19 pandemic struck, that crisis has illuminated the challenges with the existing UI infrastructure. This report includes specific recommendations that can inform the federal and state response to the unprecedented volume of unemployment claims during the pandemic, as well as ideas for longer-term reforms.

What Is Benefits Modernization?

Benefits modernization is the process of moving the administration of unemployment benefits from legacy mainframe systems to a modern application technology that supports web-based services. Many of these mainframe systems were programmed with COBOL, a long-outdated computer language. A few states began to upgrade their systems in the early 2000s, with the pace picking up after targeted federal funds were made available to support modernization in 2009.

Unfortunately, many of the initial modernization projects encountered significant problems. Some were abandoned altogether, while others were poorly implemented. Too often, workers paid the price through inaccessible systems, delayed payments, and even false fraud accusations. The COVID-19 pandemic, which led to an unprecedented spike in unemployment claims, has further exposed weaknesses in these systems.

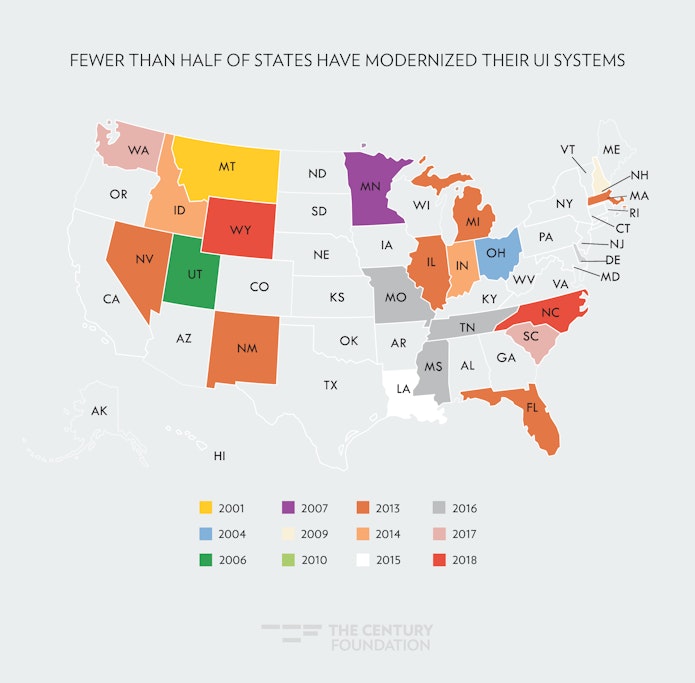

To date, fewer than half of states have modernized their unemployment benefits systems. Several have plans to modernize or are already in the midst of modernizing. The guidance in this report is meant for them, as well as for modernized states that are looking to improve their systems.

Research Methods

The findings and recommendations in this report are grounded in interviews with officials from more than a dozen states and in-depth case studies of modernization in Maine, Minnesota, and Washington, conducted from October 2018 to January 2020. The case studies involved many hours of in-person discussions with agency leadership and staff, focus groups with unemployed workers, and interviews with legal services organizations, union officials, and other stakeholders.

The report provides lessons for states no matter which pathway to modernization they choose. In fact, the three states featured in the case studies took notably different approaches. Minnesota was one of the first to modernize in 2007, and while it used a private vendor, the code remains the property of the state agency. Washington contracted directly for a proprietary commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) system which rolled out in 2017. Maine also modernized in 2017, but as part of a consortium, meaning that it shares system and maintenance expenses with two other states (Mississippi and Rhode Island).

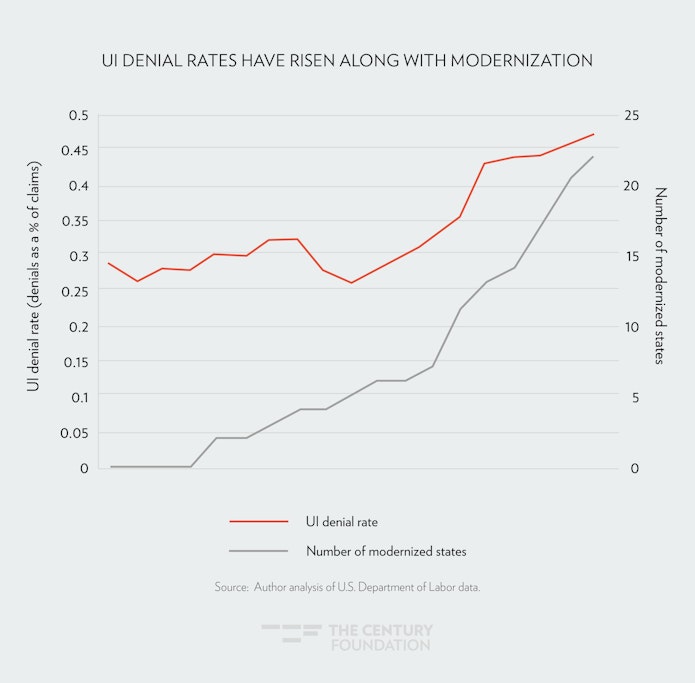

To complement the interviews and case studies, this report presents new data analysis, suggesting that while timeliness in processing claims and paying benefits improved in many states after they modernized, denial rates went up for workers seeking benefits and the quality of decisions declined.

The report also examines the growing use of artificial intelligence and predictive analytics in unemployment insurance. It concludes that, while some of these tools can improve operations and potentially help workers better understand program requirements, major concerns about fairness, accuracy, and due process remain.

Recommendations

The single strongest recommendation in this report is for states to place their customers at the center of a modernization project, from start to finish. The biggest mistake states made was failing to involve their customers—workers and employers—at critical junctures in the modernization process. This led to systems touted as convenient and accessible, but which claimants often found challenging and unintuitive. Customer-centered design and user experience (UX) testing are widely accepted best practices in the private sector, and should be a core part of any UI modernization effort.

At the planning stage:

- setting a realistic timetable and to avoid rushing implementation;

- embedding talented agency staff in a modernization effort and getting their buy-in every step of the way;

- asking customers what they need;

- being willing to revamp the agency’s business processes along with the technology; and

- identifying key conditions up front in an RFP (for agencies using outside vendors).

At the design stage:

- getting user feedback from a broad range of stakeholders;

- allowing plenty of “sandbox” time for agency staff; and

- building in a set of key features that will help customers and reduce the burden on agency staff.

At the implementation stage:

- not going live in the November–March period, when seasonal claims rise;

- considering rolling out pieces of a new system in stages;

- training and supporting staff on an ongoing basis;

- staffing up call centers and deploying additional staff to career centers;

- having a robust community engagement plan;

- expecting bugs and having a process in place to fix them; and

- providing for ongoing feedback from customers and front-line staff.

The pandemic has revealed how critically important unemployment insurance is to workers, their families, and the broader economy. By following the steps outlined in this report, states can build stronger unemployment systems that deliver the services and benefits their customers need.

What States Can Do Right Now

The release of this report coincides with the emergence of one of the greatest challenges the unemployment insurance system has ever faced: the COVID-19 pandemic. More than 10 percent of the workforce filed initial claims for unemployment in a three-week period in March and April, and job losses continued to rise thereafter.

State systems have been overwhelmed by the basic task of accepting claims, and workers are frustrated. Luckily, there are immediate steps states can take to improve access, even within outdated systems. Some states are already moving to implement these reforms, and others should follow their lead as quickly as possible.

Michigan is a good example of a state that has turned around a poorly engineered system into one that is serving workers well during the pandemic. While the original system had been modernized, the new system was designed with a faulty algorithm that inaccurately flagged workers for fraud and cut off benefits at every decision point. A new governor appointed a claimant representative to head the agency, and less than a year later, the system faced the massive challenge posed by the COVID-19 outbreak. The new leadership identified places in the system that placed an unnecessary hold on benefits and turned off those chokepoints. As a result, the agency became the second-fastest in new benefit processing among the ten states with the largest numbers of claims,1 and one of the first states to stand up the new Pandemic Unemployment Assistance benefit and the Pandemic Unemployment Compensation benefit authorized by the CARES Act.

Our recommendations for what states can do now come from our study of best practices at the state level. While states are unlikely to be able to fully replace their UI systems in the midst of this crisis, they can and must improve their technology. Here are six key areas for immediate improvement.

First, unemployed workers need 24/7 access to online and mobile services. We live in a country where you can shop online at any hour of the day. Filing for unemployment shouldn’t be restricted to nine to five on weekdays.

Second, unemployment websites and applications must be mobile-optimized. More people have mobile phones than desktop or laptop computers, and public access to computers has vanished in an era of social distancing. Low-wage workers and workers of color are particularly likely to rely on their phones for Internet access. While more than 80 percent of white adults report owning a desktop or laptop, fewer than 60 percent of Black and Latinx adults do. States must also allow workers and employers to email documents or upload them from their phones.

Third, states should update their password reset protocols. In some states, workers must be mailed a new password; in others, staff cannot process claims because they are busy answering phone calls about password resets. Technology exists for states to implement secure password reset protocols that do not require action by the agency, which saves time for everyone.

Fourth, states can use call-back and chat technology to deal with the unprecedented volume. These short-term fixes could become part of a permanent solution. “Call back” systems return a worker’s phone call instead of making them wait on hold. Chat-bots, live chats, and thought bubbles can define terms and answer simple questions for workers filing online.

Fifth, states should adopt a triage business model. Many of the questions coming into the call centers relate to passwords or claim status. Using a triage model, states can quickly train staff to handle this part of the volume, and leave more challenging questions to more experienced staff.

Finally, civil rights laws require that states translate their websites and applications into Spanish and other commonly spoken languages. Right now, an unemployed worker with limited English skills may have no choice but to file an application over the phone with an interpreter. With so many seeking help, workers may never get through on the phone or can get stuck on hold for hours. Translating online materials would not only ensure equal access, but also be more efficient.

Even if these measures take a number of weeks or months to implement, the investment would be well worth it. The employment crisis triggered by the pandemic has highlighted gaping holes in accessing unemployment, but it has also created an opportunity. We can build twenty-first-century systems nimble enough to handle disasters and designed to meet the needs of customers who are depending on access to unemployment insurance in this traumatic time.

Introduction

Unemployment insurance (UI) is the nation’s primary social program for jobless workers and their families. The federal–state UI program was established by the Social Security Act of 1935, providing critical income support for workers contending with a national unemployment rate of approximately 30 percent during the Great Depression. More recently, UI was credited with reducing poverty, empowering workers, and stabilizing the economy during the Great Recession.2 The benefits available through these programs keep workers economically stable during periods of job loss, often meaning the difference between losing access to vital job search resources like a phone or a car, or basic necessities like a roof over one’s head and food on the table.

While the research for this report was conducted before the COVID-19 crisis erupted, the current economic crisis has put into sharp focus the need for strong unemployment systems. Between March 14 and April 25, 30 million Americans—one-fifth of the workforce that is covered by unemployment insurance programs—filed an initial application for unemployment benefits. These workers experienced overwhelmed phone lines and websites, and most importantly, excruciating delays in receiving benefits. As the crisis erupted in March, only 14 percent of the 11.7 million jobless workers who filed claims received a UI payment. A recent survey revealed that for every ten workers who were able to file for unemployment insurance, three to four additional workers tried to apply but could not get through UI systems to make a claim, and two additional people did not try because it was too difficult.3

This report explains efforts by states to modernize unemployment benefits systems—many of which still to this day rely on 1980s technologies such as mainframe computers running on COBOL programming language—and explores ways for these new systems to realize their potential to be more customer-friendly and scalable to challenges like the ones states face today. In looking at challenges and best practices among states, we also identify actions states can take right now, even before modernization, to improve the experience of workers and the performance of UI systems.

Most importantly, as states and the federal government look to rebuild the backbone of this crucial safety net anew, our report suggests a new customer-driven approach geared to meet the needs of jobless workers reaching out for help during the long economic recovery ahead and future economic crises. As those new systems are built, the practical realities of workers’ lives must be kept front and center. Our analysis finds, for example, that states that modernized their benefits systems were more likely to deny benefits because they have imposed more stringent online verification of work search activities that workers struggle to navigate. While these rules have been temporarily eased in many states during the COVID-19 crisis, they could become a major factor as the economy opens up.

While a few states began to modernize in the early 2000s, this trend picked up around the time of the Great Recession, as states began looking for technological improvements that could streamline business processes, reduce costs, and provide better security and privacy protocols for the massive amount of data maintained by the UI system. These UI benefit modernization projects involved moving state unemployment benefits and appeals systems from a “legacy” mainframe-based system to an application technology that supports web-based services. They gained significant traction as states received targeted federal funds in 2009. These upgrades were necessary for security; one state secretary of labor described the mainframe system as held together by “bubblegum and duct tape.”4 The upgraded systems also offered customers the potential for more convenient online filing, notification of claims progress, and appeal filing.

Some early modernization efforts were unsuccessful. As of 2016, 26 percent of projects had failed and been discarded; 38 percent were past due, over budget, or lacking critical features and requirements; and 13 percent were still in progress. System failures can have disastrous human consequences. UI systems that are poorly planned and lack critical user testing limit claimants’ ability to access benefits, and sometimes cut them off from benefits entirely. Many states experienced significant lock-out issues when claimants had no easy way to reset their online account passwords.5 Florida cut off all points of access to its system for anyone not using the online tools, creating significant barriers for workers with language access, computer literacy, or broadband access issues. Systems that incorporated automated decision-making processes generated tens of thousands of incorrect fraud determinations that put workers into massive debt, drove them to bankruptcy, and cut off future access to unemployment benefits.6

However, the last few years have shown great improvement by states, with more states implementing full systems while at the same time controlling costs. Some states learned from past challenges and made improvements in time for challenges presented by COVID-19.

This report is the first to detail how UI modernization has altered claimant experiences. It shares the findings from interviews with officials from more than a dozen states and in-depth case studies of modernization in Maine, Minnesota, and Washington. It also analyzes publicly available UI data to run a comparative analysis of state UI programs at various stages of modernization. The report then draws on those interviews, case studies, and data analysis to present a set of recommendations for states to follow in their modernization projects.

States that have modernized acknowledge that the process is challenging and never perfect, but many have sought to learn from these experiences to build user-centric systems with positive outcomes for workers. Our hope is that this report will aid all states in doing so.

The Role of Unemployment Insurance

UI serves several key policy goals. Most obviously, it provides income stabilization for individuals who are involuntarily unemployed through a cash benefit. This stabilization extends to the local economy generally, but is critically important during times of economic downturn. The UI system also promotes attachment to the workforce and provides job search assistance and standards to prevent workers from accepting new work that is not suitable to their skills and to avoid downward pressure on wages.

Generally, during periods of recession, Congress has acted to temporarily extend benefits for workers after they exhaust their standard twenty-six weeks of state UI. During the Great Recession, state and federal UI payments totaled over $600 billion, keeping 11 million workers above the poverty line.7 Economists Alan Blinder and Mark Zandi examined the effect these payments made in the recovery, and found that every dollar in benefits paid generated $1.61 in local economic development.8 Similarly, the CARES Act of 2020 added thirteen weeks of benefits, temporarily increased payouts by $600 per week, and expanded eligibility to new categories of workers, delivering an estimated $250 billion in support to workers and the broader economy.

Maintaining the federal–state UI program is a macroeconomic balancing act. During periods of economic growth, UI agencies build up their trust funds to prepare to stabilize the workforce and economy during periods of economic recession. However, while the level of funding in a state’s UI trust fund is an important indicator of a state’s recession readiness, just as important—perhaps even more so—is a state’s ability to make benefits available to workers accurately, efficiently, and in a timely manner during a recession. As we evaluate the effect of modernizing IT systems, it is critical that we recognize access to benefits as an important countercyclical tool.

Who Does the System Serve?

UI systems have two primary customers: workers and employers. While worker benefits are the most visible part of the system, employers also interact with the UI system from both a tax and a benefit perspective.

While every state operates its program differently, in general, employers are charged for UI benefits based on their former employees’ experience with the system. This taxation system is referred to as “experience rating.” State UI taxes (assessed per the State Unemployment Tax Act, or SUTA) are levied on whatever the state sets as a Taxable Wage Base—which can vary from the first $7,000 of income to the first $46,800 each worker earns. The UI tax structure gives employers an interest in whether or not workers receive benefits, as benefit receipt can put employers on the hook for higher taxes. Employers are also included in initial investigations into benefit eligibility, receive notices about eligibility determinations, appeal determinations, and often participate in administrative hearings that address the reason a worker is unemployed.

Workers have historically been assessed for eligibility on two bases: financial eligibility and separation eligibility. Financial eligibility is based on how much money a worker earned during the qualifying base period and how often they earned money. Separation eligibility addresses why the worker is unemployed—that is, whether they left their job for a qualifying reason, such as through a layoff, a discharge without cause, or quitting for good reason.

Workers also have continuing eligibility requirements that require them to file weekly or biweekly certifications to receive benefits in which they must report any earnings, show they are able to work, and inform the state they are still unemployed. Additionally, workers’ continuing eligibility may be challenged based on their availability for work and effort made to find suitable employment. In order to interact with the system, workers must file initial claims, communicate with the agency representatives, file continuing claims, receive notices about eligibility, appeal determinations, and participate in administrative hearings.

The states are obligated under federal law to serve customers in a manner that also ensures due process. Specifically, the Social Security Act of 1935, which created the UI program, requires that the states provide for “methods of administration . . . reasonably calculated to insure the full payment of compensation “when due” and for a “fair hearing.”9 These provisions necessitate fair but also rapid and accurate administration of the program so that workers are able to receive benefits within a few weeks of losing work. Failing to conform to these requirements can trigger the loss of a tax credit to employers (per the Federal Unemployment Tax Act, or FUTA) of 5.4 percent of the first $7,000 in worker pay. The U.S. Department of Labor’s Employment and Training Administration (ETA) plays a critical role enforcing these federal safeguards and ensuring compliance by the states.

Racial Equity Implications of the UI System

The evidence suggests that institutional racism plays a significant role not only in unemployment but also in access to UI systems. If we look at the racial equity implications of modernizing UI systems, we see a compelling reason to center the experiences of Black and brown workers.

Higher Unemployment Rates

Black and Latinx workers face labor market obstacles and exclusions due to hiring discrimination rates that have remained unchanged over the past twenty-five years.10 The unemployment rate for Black workers across almost every level of education has remained double that of white workers for nearly forty years.11 And in the ten largest majority-Black cities, the unemployment rate of Black residents was 3.9 to 10.8 percent higher than that of white residents.12

Lower UI Benefits

Despite facing higher rates of unemployment, evidence shows that Black and Latinx workers do not receive UI benefits at the same rate as white workers. In 2010, following the Great Recession, non-Latinx Black unemployed workers had the lowest rates of receiving UI benefits at only 23.8 percent, compared to 33.2 percent of non-Latinx white unemployed workers; meanwhile, only 29.2 percent of Latinx unemployed workers received benefits.13 Between April 27 and May 10, 2020, over 71.5 percent of Black unemployed women did not receive unemployment benefits, compared to just 54 percent for white unemployed women.

Racial Wealth Gap

Applying for unemployment insurance during normal times can be a complicated and arduous process; add in a built-in waiting week policy in many states, and workers are often left struggling with a gap in income. With somewhere from half to 74 percent of all workers reporting they live paycheck to paycheck, a wait for a UI check—or no check at all—can be painful.14 This is particularly true if a worker doesn’t have wealth to fall back on. Being able to wait for unemployment benefits is a luxury afforded to those with savings and wealth; and unsurprisingly, this nation’s racial inequities have created a racial wealth gap.

America’s laws and policies have deprived people of color of an equitable share of the nation’s wealth. The typical net worth of a white family is nearly ten times that of a Black family and seven times that of a Latinx family.15 And more than 25 percent of Black households have zero or negative wealth, compared to less than 10 percent of white households.16 Without wealth to fall back on, workers of color are even more harmed by inefficient and ineffective systems.

Racial Wage Gap

Racial wage gaps mean lower earnings, resulting in smaller UI benefits. Black men earn just 73 cents—and Latinx men earn just 69 cents—for every dollar earned by a white man.17 And while the overall gender wage gap means that for every dollar earned by a white man, the average white woman just makes 79 cents, women of color earn even less: 62 cents for Black women, 57 cents for Native American women, and 54 cents for Latinx women.18

Digital and Mobile Divide

How people access information regarding and apply for unemployment benefits is also impacted by race. More people have mobile phones than desktop or laptop computers,19 and unemployment websites and applications that are not mobile-responsive disproportionately place a burden on workers of color. Twenty-five percent of Latinx and 23 percent of Black adults, compared to just 12 percent of white adults, are entirely smartphone dependent and do not use broadband at home.20 While more than 80 percent of white adults report owning a desktop or laptop, fewer than 60 percent of Black and Latinx adults do.21 And when it comes to job searches, 55 percent of Black and Latinx workers, compared to just 37 percent of white, use their smartphone to get information about a job; and when applying for jobs, Black and Latinx workers are more than twice as likely than white workers to apply for a job using their mobile device.22 Ensuring all workers can navigate the UI system requires access to mobile-friendly programs.

Biased Algorithms

According to the research institute Data & Society, “algorithms can be incredibly complicated and can create surprising new forms of risk, bias, and harm.”23 Algorithmic systems can have bias in multiple places, including biases introduced through data input or by the algorithm creator.24 One of the problems with algorithmic systems is that they often make decisions that result in different outcomes based on protected attributes, including race, even if these attributes are not formally entered into the decision-making process.25 For example, evidence shows a racial impact in medical algorithms that ignore social determinants of health or result in Black people needing to be sicker than white people before being offered additional medical help.26 Without external auditing systems that assess how the data is processed, these biases are allowed to go unchecked.27

Due to the layers of institutional racism faced by Black, Indigenous, and workers of color, we must work alongside worker leaders and organizations to create a racially just, inclusive, and truly accessible unemployment insurance system. A modernized unemployment insurance system should center the experiences of workers of color and collect data on race and ethnicity, to ensure states are adequately meeting the needs of all workers.

Administrative Funding

Critical to the viability of state UI programs is access to adequate funding for administration of the tax, benefits, and appeals systems. The federal government funds the administration of the state UI programs, including eligibility determinations, tax collections from employers, and the appeals process. State systems have been chronically underfunded, and the resulting search for efficient technology solutions is one of the principal motivators behind benefit modernization projects.

Administrative grants are tied to the amount of unemployment insurance claims paid out by the state and therefore drop when there are improvements in the economy and declines in UI recipiency. As a result, federal grants for the administration of unemployment insurance declined by 30 percent from 1999 to 2019 on an inflation-adjusted basis.28

These funding levels during this period were barely enough for states to manage the basic staff needed to operate their UI programs, let alone upgrade and maintain unemployment insurance technology. The approximately $2 billion in annual federal funds available to states before the COVID-19 crisis left state UI programs with threadbare staffs that struggled to address the sudden and major surge of claims. In particular, states lacked flexible technology that could quickly incorporate law changes, bandwidth to process claims, and enough trained staff to ramp up call center and adjudication operations that require interactions with claimants. While the federal government provided an additional $2 billion in state UI administrative funding under the Families First Coronavirus Response Act, which is allowing the states to increase staffing and pursue short-term technology improvements to respond to COVID claims, the “boom and bust” cycle of federal funding is inconsistent with the needs of the states for stable levels of funding to sustain their UI programs.

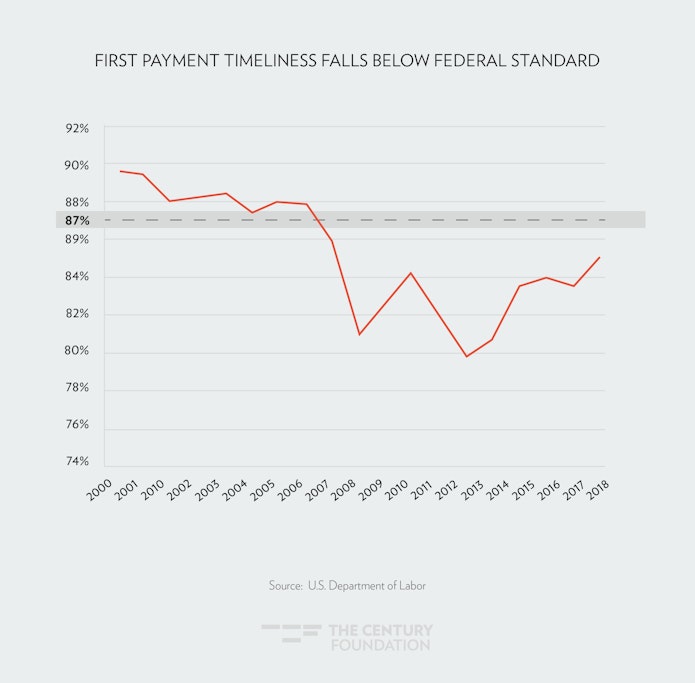

Federal regulations stipulate that states should deliver a first payment to at least 87 percent of eligible applicants within fourteen or twenty-one days from their initial claim for benefits (the difference is that those states with a waiting week are given 21 days to make a payment).29 The national average of first payment timeliness dropped below the national standard in 2008, which was understandable, given that the surge of unemployment in the early years of the Great Recession came before states got more administrative dollars from the formula. However, timeliness did not recover, even when UI claims fell to their lowest level in fifty years. Throughout our interviews, state officials consistently complained about having to juggle staffing to meet all their requirements, including taking claims, and cited low administrative funding as a reason for driving more claimants to online initial applications.

FIGURE 1

As a result, states have been forced to look for supplemental funding. Between 2007 and 2016, the National Association of State Workforce Agencies reported a 115 percent national increase in state supplemental spending for UI administration. As of 2017, seventeen states and territories reported the use of a state administrative tax to supplement administrative costs; nine states reported using general revenue, while twelve states said they used other sources for administrative funding.30The federal government has periodically, but not consistently, provided additional funding that has supported benefits modernization projects, as discussed further below (see “The Federal Role”).

Benefit Modernization: Where Are We Now?

Since the early 2000s, states have been working toward upgrading their UI technology. Driven by concerns about data security and privacy, administrative costs, and efficiency, states have tried a variety of methods to either wholesale replace their systems or gradually improve their components. Most have done so through contracts with private vendors, sometimes as part of a consortium, where system and maintenance expenses are shared across a group of states, but the product itself is customized to some degree to each participating state’s needs. At least one state, Idaho, handled its modernization project entirely in house.31 Consortium models hold the potential to generate even more financial savings if other states join the consortium later, but states still have to navigate governance issues.

For many years, modernization projects trended in the red—encountering significant cost overruns and schedule delays, with several states actually pulling their projects. As noted in the introduction to this report, as of 2016, 26 percent of projects had failed and been discarded; 38 percent were past due, over budget, or lacking critical features and requirements; and 13 percent were still in progress.32 However, the past few years have shown great improvement, with more states implementing final systems while controlling costs.

As of 2019, twenty-two states had completed modernization projects for their UI benefits systems and twenty-one states completed modernization projects for their UI tax collection systems (sixteen states have completed both). Thirteen states reported having UI modernization projects in development,33 including two—Ohio and Montana—that are re-modernizing after an early 2000s implementation.

figure 2

TABLE 1

| States That Modernized Their UI Systems, By Year | |

| Montana | 2001 |

| Ohio | 2004 |

| Utah | 2006 |

| Minnesota | 2007 |

| New Hampshire | 2009 |

| Illinois | 2010 |

| Nevada | 2013 |

| New Mexico | 2013 |

| Michigan | 2013 |

| Massachusetts | 2013 |

| Florida | 2013 |

| Indiana | 2014 |

| Idaho | 2014 |

| Louisiana | 2015 |

| Tennessee | 2016 |

| Mississippi | 2016 |

| Missouri | 2016 |

| Washington | 2017 |

| South Carolina | 2017 |

| Maine | 2017 |

| Wyoming | 2018 |

| North Carolina | 2018 |

| Source: NASWA Information Technology Support Center & Author’s analysis | |

The completed modernization projects have encountered significant problems, including numerous delays, issues with testing, data conversion errors between legacy and new systems, data loss and security issues, and poor training of staff who interact with claimants. For example, Massachusetts’ modernized system, built by Deloitte, was $6 million over budget and, after rolling out two years late, was riddled by implementation problems.34 Call center wait times doubled, and there were 100–300 claimant complaints per week, owing in large part to a major increase in system-generated questionnaires to claimants, which delayed claims processing.35

While Tennessee’s system was developed by a different vendor, Geographic Unemployment Solutions, they experienced some of the same problems as Massachusetts: the system auto-generated numerous non-critical questions about applications that had to be cleared by staff, and the backlog for responding to user questions about claims stretched to eighty-two days after the system was rolled out in May 2016. Data conversion problems between the legacy and new system caused delays in payments, all during an implementation that a legislative audit later concluded was rushed.36

In several other states, implementation has been rushed to meet external deadlines, leading to situations like that in Maine and Washington (described in depth in the case studies) where the state’s system was not ready for a surge of claimant questions, glitches caused the system to go down after launch, and repeat problems with core elements like passwords could not be solved.37

Florida’s CONNECT system was riddled with timeliness and accuracy problems when it launched, including more than 400,000 claims documents that were stuck in an “unidentified” queue and unable to be processed.38 The implementation of the new system coincided with a new requirement that claimants report five employer contacts per week, which could only be reported online through the new system. As described in a previous NELP report, “the number of workers disqualified because DEO [the Florida Department of Economic Opportunity] found they were not ‘able and available for work’ or not ‘actively seeking work’ more than doubled in the year following the launch of CONNECT, even though weekly claims declined by 20 percent in that same year.”39 The U.S. Department of Labor Civil Rights Division found that this aspect of the system had a discriminatory effect on Limited English Proficient claimants who struggled the most.40 New Mexico’s modernization implementation also faced a civil rights complaint from a legal service organization based on multiple language access problems, including an elderly Spanish-speaking farm worker who was told he could file online in a site that was only in English.41

The U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) has issued guidance advising states to move away from phone-based work-search verification and instead move to online collection of work search activities through a case management system.42 But as was demonstrated in Florida, verifying details of job-seeking efforts (such as details of job applications submitted) online can be a hurdle for many claimants who have difficulty navigating online systems, like those with limited English proficiency.

The DOL guidance on work search is one aspect of the department’s focus on “program integrity;” that is, reducing the incidence of payments made in error. There have been several supplemental federal appropriations related to program integrity, which have been used to fund modernized systems featuring new models to detect improper payments and assess fraud. In one such instance gone badly awry, the state of Michigan used an automatic determination process that falsely charged more than 20,000 claimants with improperly collecting unemployment benefits (such as by both working and collecting UI benefits).43

This report intends to help modernizing states learn from the challenges these early-adopting states faced. It is clear from the research done for this report that UI modernization is maturing, with several states joining forces in consortia in an attempt to reduce the costs of development and maintenance of their system. Moreover, states are benefiting from products that have been developed by vendors specifically for UI and that have been road-tested in these early applications, and can be deployed more smoothly. Still other states have designed their own unemployment insurance technology systems, and, as in the case of Idaho, are making their technologies and expertise available to other states. Taken together, these advances put the UI system in position to improve the outcomes of UI modernization, both among those states that have yet to modernize and who are looking to improve their systems. At the same time, it is important to learn from the ways that COVID-19 pandemic has tested and stressed these systems, and how states have responded.

The Federal Role

While each state UI agency is responsible for its own benefit modernization project, the federal government plays a critical role in funding the projects and oversight to ensure compliance with the legal safeguards requiring fair and timely processing of benefits. Congress has also played a monitoring role, assisted by research provided by the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), which issued a series of reports addressing the severe staffing, phone claims system, and IT challenges that compromised access to benefits during the Great Recession.44

Funding

Federal funds have been critical to many benefit modernization projects. During the Great Recession, Congress authorized the release of federal trust fund dollars (called “Reed Act” distributions, which are based on each state’s share of FUTA revenues) to the states to stabilize the solvency of their state trust funds, expand benefits, and support UI administration. In 2009, as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, Congress passed the UI Modernization Act, which created an incentive program for the states to expand UI benefits for low-wage and part-time workers, many of whom are women, while also helping the states make critical investments in IT, staffing, and other UI administration needs. From 2009 to 2011, 39 states claimed about $4.5 billion in incentives to improve UI systems, including improving technology.45

In addition, in recent years, DOL has made varying amounts of supplemental funding available to support state consortia and state IT needs. However, that funding has been limited and typically comes with a number of strings attached, such as mandates that the systems are designed to identify UI overpayments and assurances that the projects would be completed with other sources of funding, if necessary to cover the full cost.

Oversight

DOL’s Employment and Training Administration (ETA) has set some standards in response to the growing reliance of states on technology to process UI benefits. Of particular significance, in 2015, ETA and DOL’s Civil Rights Center issued state guidance entitled “State Responsibilities for Ensuring Access to Unemployment Insurance Benefits,”46 which relied on the federal UI and civil rights laws to clarify where technology can compound problems of access to UI benefits facing many unemployed workers. On May 11, 2020, DOL updated this 2015 guidance in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, pointing out to states the requirement that they translate vital written, oral, and electronic information into languages spoken by a significant portion of the eligible or affected population, as defined by Department of Justice guidelines.47 Moreover, states must provide access to people with disabilities, including online enrollment systems that incorporate modern accessibility standards for deaf, blind, and otherwise disabled applicants.

This comprehensive interpretation of federal law provides a template for states to ensure full and fair access to benefits when modernizing their IT systems. The federal guidance clarifies that the “use of a website or web-based technology as the sole or primary way for individuals to obtain information about UI benefits or to file UI claims may have the effect of denying or limited access to members of protected groups in violation of Federal nondiscrimination law.”48 It goes on to caution that the state UI agencies “must also take reasonable steps to ensure that, if technology or other issues discussed in this [guidance] interfere with claimants’ access, they have established alternative methods of access, such as telephonic and/or in-person options.”49

On a separate track, in 2018, DOL rolled out a “pre-implementation planning checklist” for states to follow, which candidly recognizes that “recent efforts by states in launching new IT systems have resulted in unexpected disruptions in service to customers, delays in payment of benefits, and the creation of processing delays.” 50Before going “live” with a new UI benefit or tax IT system, the states are required to submit a report to DOL indicating that they have reviewed and addressed each element of the checklist,51 which covers all phases of the process, including functionality and testing of the system, customer access and usability, policies and procedures, implementation preparation, call center operations readiness, vendor support, communications, training and other core functions and activities.52

The checklist was developed with the assistance of the Information Technology Support Center (ITSC), which is operated by the national organization of state UI and workforce agency administrators (called the National Association of State Workforce Agencies, or NASWA). ITSC also provides UI IT modernization resources online and other services funded by DOL grants, which are available only to NASWA members. ITSC also provides consulting services at the initial planning phases of a state’s UI IT project.

To date, only a limited number of states have launched new systems that require submission of the planning documents. ITSC is not responsible for reviewing the pre-implementation planning documents to evaluate their compliance with the checklist. And given its limited resources and expertise in UI IT planning and implementation, ETA is likely to defer to the judgement of the states in evaluating the planning documents.

Recommendations for States

This section presents our full list of recommendations to states on how to plan, design, and implement a UI benefits modernization project. These recommendations are grounded in interviews with officials from more than a dozen states; in-depth case studies of UI modernization projects in Maine, Minnesota, and Washington; and analysis of data on UI system performance from all fifty states. (See the remainder of this report for these materials.) This list of recommendations presents:

- best practices, as identified in our interviews and case studies of state UI modernization projects;

- lessons learned about missteps to avoid; and

- best practices from beyond UI, looking at both the public and private sectors.

These recommendations will be most applicable to states that have not yet modernized, or who are in the midst of modernization. However, they may also be helpful to states that have already modernized but are looking to improve their systems.

We recognize that state UI agencies operate with limited human, financial, and technological resources. Nonetheless, we believe the recommendations presented here are achievable even within those constraints, particularly if federal funds are available to bolster state efforts.

We have structured our recommendations to follow each of the three major stages of modernization: planning, design, and implementation. Our single strongest recommendation is to place customers at the center of the project, from start to finish. The biggest mistake we saw states make was failing to involve workers at critical junctures in the modernization process. This led to systems touted as convenient and accessible, but which claimants often found challenging and unintuitive. Customer-centered design and user experience (UX) testing are widely accepted best practices in the private sector, and should be a core part of any UI modernization effort.

Stage 1: Planning

Recommendation 1.1. Set a realistic timetable. Many state officials interviewed for this project said they regretted allowing too little time and having to rush implementation. Allow ample time for planning and design, including user testing and refinement, before you roll out a new system.

Recommendation 1.2. Get buy-in from agency staff. Modernization projects demand full commitment and cooperation across all agency divisions. It may be challenging to divert talented staff away from their daily responsibilities, but to succeed, you have to embed them in the modernization effort and get their buy-in every step of the way. Experienced staff can draw on their institutional knowledge to inform operational change management. Staff with coding experience can help ease the data migration from legacy systems. Seek their input early, to inform your RFP (if you are using an outside vendor) and make sure you don’t omit anything critical.

Recommendation 1.3. Ask customers what they need. As part of your initial needs assessment, reach out to unemployed workers and employers, and ask them what they would like to see in a modernized UI system. Agency staff will provide valuable input, but there is no substitute for going straight to your customers.

Recommendation 1.4. Be willing to revamp your business process. As you plan your modernization project, don’t be held back by your current business process. Assume it can and will change, rather than designing your new system around processes that may no longer make sense in a new environment.

Recommendation 1.5. Identify key conditions in your RFP. If you are using an outside vendor, making these three conditions clear in your RFP will help you negotiate a contract that sets you up for success.

1.5.1. Retain control of the go-live date. You don’t want to be rushed by a vendor into rolling out a new system before you are confident that you are ready.

1.5.2. Allow for extensive usability testing by your staff and customers. Some vendors only test out a product with their own software engineers, a narrow approach known as user acceptance testing (UAT). Make sure you have the opportunity for broader user experience (UX) testing, to gather input from workers and employers in your state.

1.5.3. Provide for tech support after the go-live date. Even the best-planned modernization project will not roll out perfectly. Require the vendor to train your staff in advance so they can handle issues as they arise and make changes to the system. In addition, make sure the vendor remains available to you after rollout without further costs.

Stage 2: The Design Process

Recommendation 2.1. Get user feedback from a broad range of stakeholders. Create ample opportunities throughout the design process for workers and employers to try out features of your system, and tell you what makes sense to them and what doesn’t. There are others who will use the system frequently and should be involved in testing as well. They include labor unions, legal aid organizations, community groups, and other social service agencies. Be sure to compensate members of the public for their time and transportation costs when you invite them to participate in focus groups or other consultations.

Pennsylvania and Massachusetts Listen to Stakeholders

Two states have now created mechanisms for stakeholder involvement and feedback in these projects. In 2017, Pennsylvania’s legislature created the “Benefit Modernization Advisory Committee” in the bill that provided funding for Pennsylvania’s new project.53 The small committee consists of employer, labor, technologist, and claimant representatives, along with three agency staff members who will use the new system. By law, the committee:

– meets at least quarterly with project and agency leadership;

– receives monthly updates on the project;

– monitors the implementation and deployment of the project, providing feedback and both formal and informal recommendations; and

– submits a yearly report of the project’s process and the committee’s project recommendations to the legislature.

In 2020, Massachusetts’ legislature created a similar advisory council in the funding mechanism for upgrades to the modernized system that was deployed in 2013, and includes the council in the bid selection process.54 The advisory council has similar responsibilities to Pennsylvania’s committee, but had broader stakeholder involvement, creates greater project transparency, and requires feedback from vulnerable communities:

[T]he advisory council shall solicit input on the criteria utilized for the selection of the bid evaluation from low-wage unemployed workers, people with disabilities who use assistive technology, community-based organizations that advocate for people with limited English proficiency, people of color, recipients of unemployment benefits and individuals with technological expertise in systems designed to maximize user accessibility and inclusiveness.55

Recommendation 2.2. Allow plenty of “sandbox” time for agency staff. Create both structured and unstructured opportunities for staff to experiment with features of the system as it is being developed and recommend improvements.

Recommendation 2.3. Build in key features that help customers and reduce the burden on agency staff. While the precise design of your system should be guided by the needs of your customers and staff, there are a set of features that we recommend building into any system (and writing into your vendor contract).

2.3.1. Create a substantive, accessible claimant portal. Customers should be able to access a portal where they can perform all essential tasks: filing an initial claim, continuing claim, or appeal; checking on the status of a claim or appeal; completing fact-finding questionnaires; uploading documents and evidence, and reviewing correspondence.

2.3.2. Go for a professional look. Your website should present your agency as the professional operation that it is. The interface should look like the private sector websites customers are used to encountering; if it doesn’t, customers may be less likely to trust it, resulting in higher call center volume and more paper applications.

2.3.3. Make your website mobile-optimized. More people have mobile phones than desktop or laptop computers. 56 Low-wage workers and workers of color are particularly likely to rely on their phones for Internet access.57While more than 80 percent of white adults report owning a desktop or laptop, fewer than 60 percent of Black and Latinx adults do. 58 Some states had already been planning to optimize their sites for mobile access before the COVID-19 pandemic struck; Connecticut, for example, quickly made that change afterwards. There’s no need to build an app; just make sure your website reformats automatically for mobile devices.

2.3.4. Design a sensible password reset process. At the start of the pandemic, a major source of delay in filing unemployment claims was the overwhelming number of people getting locked out of their accounts. Technology exists to implement secure password reset protocols that do not require the mailing of a new password or other action by agency staff. Using those protocols saves time and frustration for everyone.

2.3.5. Make online and mobile systems available 24/7. In an era when online commerce and banking happens at all hours, workers expect similar access to the UI system. Allowing claims to be filed at any time also reduces pressure on the system when demand surges, by spreading out the claims.

2.3.6. Automatically save incomplete applications, and provide a warning before timing out. Too many systems kick customers out before they have completed their claim. Auto-save can prevent them from having to start all over again if they leave their applications open on their screens for too long while searching for information. Providing a warning before a customer is timed out is an added safeguard, but doesn’t substitute for auto-save.

2.3.7. Allow customers to choose email or texting as a communications method. It is unrealistic to expect that customers will constantly log back into the system to check for updates. Push information out through email or text, and allow customers to choose which method works best for them. Minimize the use of mailed documents; if it is required by law, make that clear to customers.

2.3.8. Permit customers to email in or upload documents from a computer or mobile device. The system should be designed to allow photographs and scans of documents to be easily submitted. This is how mobile banking works; UI should be no different.

2.3.9. Avoid automated decision-making. Technology can streamline many aspects of UI, but allowing computers to make decisions is inconsistent with the requirements of due process. As a safeguard against AI-driven error, several of the states we studied required a staff member’s involvement before a claim could be denied.

2.3.10. Use plain language and smart questioning. Use simple, non-bureaucratic language. It may help to gather information from customers through a series of straightforward questions; a vendor we interviewed suggested thinking of the claims process as an interview, rather than a form to fill out. For example, many people use the terms “laid off” and “fired” interchangeably, so posing a series of simple questions about why they lost their job could provide better information and thus reduce errors.

2.3.11. Translate the application and other online materials into Spanish and other commonly spoken languages. Civil rights laws require translation of materials to ensure equal access. Translating materials also can save states money, by reducing demand for interpretive services at call centers. Washington provides an entirely Spanish-language version of its website and application, for example.

2.3.12. Minimize the paperwork burdens associated with work search. If your state directs claimants to register for worksearch on a state government website to search for a job, look for a way to integrate the two systems. Provide consistent guidance about what is required and avoid unduly burdening claimants. You want people spending their time looking for work, not assembling extensive documentation that your system lacks the capacity to review. Rely instead on the Reemployment Services and Eligibility Assessment (RESEA) program for verification, as needed.

2.3.13. Coordinate technology with other state agencies. If your state plans to move to a single sign-on system, make sure the password mechanism you create can be easily integrated into that new system. If your state handles appeals in a centralized manner, make sure UI claimants can tap into information about their appeals through the UI portal.

2.3.14. Provide a view-only option for non-UI staff. Workers often go to career centers and other public agencies seeking help with UI. Constituent services representatives in legislators’ offices also receive UI inquiries. Allowing public employees to log in and see what’s happening with a claim—but not to make changes that interfere with UI processing—is a best practice that Pennsylvania has adopted.

Designing a Modern Website

Websites today include a variety of features customers are used to seeing, all of which would

enhance the functioning of a UI website. They include:

– Chatbots (to answer frequently asked questions)

– Live chat (if you have the staff capacity)

– Calendaring

– Drop-down menus

– Progress bars (to track the steps in an application)

– Hover text (to pull up the definition of a term, for example)

– Select-all options (to file a batch appeal, for example)

– Expansive character limits for text fields

– Dark/dim versions

Stage 3: Implementation

Recommendation 3.1. Don’t go live during the busy season. It’s best to avoid the November–March period, so you are not struggling to adjust to a new system at a time when seasonal claims surge.

Recommendation 3.2. Consider rolling out pieces of the new system in stages. Going live with just one element, like the appeals process or Disaster Unemployment Assistance (DUA) claims, gives you a chance to see how the new system is working and make refinements, before everyone has to use it. Idaho and Washington have taken this approach.

Recommendation 3.3. Train and support your staff before going live, and on an ongoing basis. Modernization means making big changes, not only to your computer systems but likely to your business process as well. Your staff, including those on the front lines in call centers and career centers, should feel well prepared for those changes and supported throughout the transition. Maine and Wisconsin reported that call center locations that received the most practice with the new system were the best prepared for the rollout. Minnesota also provided guidance to its staff on how to respond in an empathetic manner to claimants struggling with their new system.

Recommendation 3.4. Staff up your call centers and deploy staff to career centers before going live. Call center usage spikes dramatically when a new system is rolled out, as does the number of people seeking assistance with UI at career centers. Minnesota put additional staff on the phones and Maine placed staff at career centers before going live with the new system, to help manage the demand. If you don’t anticipate being able to answer calls without substantial delays, add a call-back option, as Washington did.

Recommendation 3.5. Have a robust community engagement plan. Your rollout shouldn’t catch the community by surprise. Reach out in advance to stakeholders, educate them about the new system, and ask them to help spread the word. Tap into the same group you asked for help in testing your system before rollout (see Recommendation 2.1, above).

Recommendation 3.6. Expect lots of bugs and have a clear process in place to fix them. If you run into major problems, hold the claims, as Maine did, rather than adjudicating them, as Michigan did. Putting claims on hold during a system malfunction prevents a lot of hardship for workers, and unnecessary workload for staff who process appeals and reversals.

Recommendation 3.7. Provide for ongoing feedback from your customers and front-line staff. Washington, for example, used customer surveys to inform its decisions about business process changes. New Mexico did a particularly thorough job with the usability surveys it sent to claimants and employers. Be sure to dig deeper than just asking customers for their overall level of satisfaction with the experience. Provide the opportunity for feedback at every stage, not just at the end of a transaction, by which point customers may have forgotten exactly what language they found confusing or where they got stuck. Create a mechanism for staff to provide suggestions for improvements as well, and follow up in a timely manner.

Initial Lessons from States

In the early stages of the research for this report, the authors communicated with UI agency officials from a diverse group of about twenty states, of which over a dozen agreed to be interviewed to share the lessons learned from their experience.59Specifically, the state officials were asked to share features of their modernized systems they are most proud of, and what they would do differently if they were just starting the process. Most of the states interviewed had completed the transition to modernized benefits processing, and the remaining states were fairly far along in their development.

Highlights from these initial interviews are presented below, structured to follow the three stages of a modernization process: planning, design, and implementation.

1. Planning Lessons from State Interviews

- Funding is key. As one state official emphatically put it, “FUNDING these projects is the greatest obstacle of all!” Many states relied primarily on the one-time large infusion of flexible “Reed Act” funding resulting from the 2009 Recovery Act, while others (e.g., Colorado, Utah, and Washington) accessed dedicated state funding or special tax assessments to support their programs. Some agencies have sought out a specific funding mechanism. For example, Pennsylvania currently has an employee-side tax, and at the UI agency’s request, the legislature directed some of the revenue from that tax to fund its current modernization effort.

- State consortia can be challenging to form, but useful. Most states reported serious challenges forming UI IT consortia due to restrictions on federal consortia funding for such consortia, changing priorities of state political leaders, and other factors. As a result, many UI IT modernization efforts were significantly delayed or altogether abandoned in some cases. However, some states have valued and benefited from the formation of consortia to share UI IT infrastructure, expertise, and costs (including the Mississippi/Maine consortium and the Idaho/Vermont/North Dakota consortium).

- Strong teams representing all functions should be involved in the planning process. Several states (e.g., Utah, Washington, Vermont) emphasized the importance of assembling strong teams that represent all the major functions of the agency to be involved in the planning, design, and implementation processes, and develop the expertise in the new systems. The team members should also play a central role providing the training of the system to front-line staff, both before the system is launched and on a continuous basis thereafter, while also regularly engaging the staff to solicit feedback on the system.

2. Design Lessons from State Interviews

- New internal staffing structures and business practices may be needed. Some states (e.g., Minnesota, New Mexico) emphasized the importance of creating internal staffing structures to more efficiently and effectively process and adjudicate UI claims. These “unified integrated” systems break down traditional agency staffing silos (e.g., creating separate units that handle initial UI claims, adjudications, and overpayments) and instead apply UI staff where they are most needed (e.g., responding by phone to resolve more complicated UI adjudication issues).

- Investments in internal IT systems and expertise can be valuable. Several of the states interviewed (e.g., Iowa, Utah, Minnesota, Washington) have worked with commercial off- the- shelf technologies, developed open-source technologies, or invested significantly to develop internal IT staffing and expertise in order to rely less on established vendors and provide greater flexibility to manage their UI IT systems.

- Data conversion should begin as early as possible. UI agency officials also recommended that states taking on new UI IT modernization efforts begin the process of data conversion from their legacy systems as early as possible and conduct extensive testing of the converted data.

- Too little usability testing was done. With some exceptions, such as usability studies in New Mexico, the interviews with UI officials clarified that there has been limited feedback solicited directly from workers or worker advocates to evaluate the usability of the new UI IT systems for all workers, but especially for the large proportion of unemployed workers whose first language is not English or who have limited computer literacy. Where outreach has been conducted, it has often taken place at the end of the planning and development process, when the opportunity to inform key decisions is more limited.

3. Implementation Lessons from State Interviews

- Rolling out new systems is challenging and can take a long time. As one state official put it, UI IT modernization is a “roller coaster” ride, fraught with funding, vendor, staffing, and automation challenges. Many of the states interviewed started the process in the early 2000s, and only recently launched their automated benefits systems. Several states also experienced challenging launches of their new systems, which required major adjustments. Accordingly, most UI agency officials strongly advised that states provide for extensive lead time and testing of the technology (e.g., Wyoming tested 1,800 cases with staff before they were put in a live environment), organize the staff to ensure that “all hands are on deck” while rolling out the new system, and perhaps most importantly, wait to launch the new system during low-volume periods (e.g., during the summer months when fewer people are applying for benefits).

- Modernization can improve UI access. Uniformly, state UI officials emphasized the significant role that new automated and IT reforms have played in improving communication with UI claimants, with twenty-four-hour access in many cases to a range of online services and direct access to information on the history and status of the individual’s claim. Indeed, the rate of online initial and continued claims filing has increased in most states that modernized. Some states (e.g., Colorado and Mississippi) have provided mobile-ready platforms, which helps workers in more rural communities that do not have reliable broadband access. New Mexico has also developed “personas” to help the platform accommodate particular groups of workers seeking to navigate the online claims systems by anticipating their needs and providing them with “pop ups” and other features that provide clarifying information. Several states (e.g., New Mexico and Mississippi) are also providing or developing “single service sign-on” systems, which allow workers to readily access not just UI benefits, but also job service and reemployment services.

- UI access “pain points” remain. Due to administrative funding limitations and other pressures, several states indicated that they are reducing access to phone-claims services, which have been critical to many workers who have more challenging claims or have experienced barriers to navigating online systems. Many states also reported that the new automated systems have generated a greater number of eligibility, disqualification, and overpayment issues, which often produce multiple unfavorable determinations that the claimant is required to respond to separately. Where possible, certain states have taken steps to intervene in a timely fashion in these cases, and at least one state (Vermont) has adopted a policy to merge these multiple determinations into a single notice and determination.

Case Study Findings

This section presents findings from detailed case studies of UI modernization in Maine, Minnesota, and Washington. All three states had completed UI IT modernization projects at the time of data collection. Their UI IT projects were generally regarded as successful in terms of current program outcomes or public response—though no modernization effort was without its unique challenges. They also represent states with different populations, economies, and labor forces, as shown in Table 1.

table 2

| Three Different Case Study States | |||

| Population | Unemployment Rate. 2018 | Major Industries | |

| Maine | 1.34 million (ranking 42nd in population nationwide) | 3.24% | Accommodation and Food Service; Retail Trade |

| Minnesota | 5.64 million (ranking 22nd in population nationwide) | 2.94% | Trade, Transportation and Utilities; Professional and Business Services; Manufacturing |

| Washington | 7.61 million (ranking 13th in population nationwide | 4.46% | Retail Trade; Manufacturing; Accommodation and Food Services |

| Source: U.S. Census Bureau July 2019 population estimates; Bureau of Labor Statistics Local Area Unemployment Statistics seasonally adjusted unemployment rate, 2018; Maine Center for Workforce Research and Information; Minnesota Employment and Economic Development; Washington State Employment Security Department. | |||

Maine, Minnesota, and Washington took different approaches to UI IT modernization. Minnesota was one of the earliest states to modernize their benefits system, which went live in 2007. Though the online platform—the Minnesota Unemployment Insurance (UI) Program—was created by private vendors BearingPoint and Deloitte, the code is the property of the state. Minnesota’s Department of Employment and Economic Development (DEED) maintains the code and shares it freely with other state agencies that request it. While building their online system, Minnesota’s UI agency was also engaged in updating their business practices. They accomplished this by reviewing call center management, scripts, and training, among other things.

Washington interviewed several technology vendors for their project. After conducting extensive market research, Washington’s Employment Security Department (ESD) ultimately negotiated a contract with Fast Enterprises that obligated the vendor to provide ongoing system support and maintenance for its commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) product. Though agency employees reported that they have a lot of oversight over the system, it is a proprietary system owned by Fast Enterprises. Unlike Minnesota, Washington’s modernization project, which was rolled out in 2017, included no operational change management.

Maine is the only case study state that is part of a consortium, meaning that it shares system and maintenance expenses with two other states (Mississippi and Rhode Island). The Maine–Mississippi–Rhode Island consortium—ReEmployUSA—uses software developed by Tata Consulting Services (TCS), a subsidiary of the multinational conglomerate Tata Group. Maine’s personalized UI system is called ReEmployME and was rolled out in 2017. Maine made reviewing agency business processes a feature of its modernization project. The consortium owns the supporting code, though TCS provides ongoing application support.

table 3

| Case Study Modernization Projects At a Glance | |||

| UI IT Program | Vendor(s) | Project Duration | |

| Maine | ReEmployME (launched 2017) | Tata Counsulting Services (TCS) | 2016–2017 |

| Minnesota | Minnesota Unemployment Insurance (UI) Program (launched 2007) | BearingPoint, Deloitte | 2003–2007 |

| Washington | eServices (launched 2017) | Fast Enterprises | 2015–2017 |

The case studies presented in this section provide a description of our research methods as well as our findings on each state’s UI IT project and its successes and challenges, with attention given to how modernization has impacted claimants.

Minnesota

Minnesota’s UI agency (the Department of Employment and Economic Development, or DEED) takes pride in its business philosophy and quality of services. It was the first state to modernize both its UI tax collection and benefit payment systems. Before the COVID crisis, Minnesota was one of the few states that regularly met the federal trust fund solvency standard. Furthermore, Minnesota does well on official performance measurements set by the Department of Labor—in 2018, Minnesota’s recipiency rate was ranked fifth highest and their average weekly benefit amount ($462.61) was ranked third highest among all state UI programs. Both measurements improved following modernization. Minnesota has been a national leader, developing and maintaining IT and claims processing systems that have been shared widely with other states. They are one of the top states in major elements of administrative performance, such as first-payment timeliness, overpayments, nonmonetary time lapse, and nonmonetary quality, a fact they are proud of. The feedback provided in focus groups by worker advocates, summarized below, generated helpful recommendations to further improve upon the Minnesota system.

TABLE 4

|

Minnesota UI Indicators and Modernization |

||||||

| Indicator | Before Modernization | Just After Modernization | Now | |||

| 2006 | Rank | 2008 | Rank | 2018 | Rank | |

| Overpayment rate | 11.70% | 15 | 10.70% | 21 | 6.50% | 44 |

| Total denials as a percent of claims | 31.50% | 23 | 30.80% | 15 | 48% | 21 |

| Nonmonetary determination separation quality | 68.70% | 25 | 76.70% | 32 | 84.80% | 11 |

| First payment timeliness | 88.60% | 39 | 88.00% | 30 | 93.20% | 9 |

| Nonmonetary determination timeliness | 82.00% | 23 | 75.90% | 19 | 88.40% | 14 |

| Percent online claims (initial) | 16.00% | 3 | 30.40% | 12 | 87.90% | 15 |

| Note: Indicators that have declined since modernization are shaded dark gray. | ||||||

Planning in Minnesota

Minnesota began planning its Unemployment Insurance Technology Initiative Project (UITIP) in 2003. Prior to UITIP, unemployment insurance was a paper-based process. During interviews, agency officials indicated that evaluating business practices and eliminating system complexities were compatible project goals.

The hallmark of the modernization project was a triage system to better manage call center operations. Minnesota’s business reorganization was intended to ensure that the majority of claims were able to be efficiently processed with minimal staff time, leaving staff to spend time on claims with more difficult issues. Under the triage system, call center staff are trained to handle common issues while transferring any exceptional scenarios to a smaller group of subject matter experts (SMEs). Project leaders observed call center staff and analyzed existing datasets to identify successful practices that could be built into the online system. These operational adjustments helped reduce work backlogs and call center wait times. Even during the Great Recession, wait times were less than three minutes, on average.

Minnesota had one of the quickest modernization processes and was able to roll out its system after sixteen months. In retrospect, the agency believed that having the project run by UI experts, rather than technology experts, was critical to its success.

The code that powers Minnesota’s online UI system was developed by third-party vendors. It was purchased by the state so that they would have full intellectual control to make any necessary or desired modifications.

Stakeholder Feedback on Planning in Minnesota

- Stakeholders were not really consulted during the planning stages of the project. While

- Minnesota has an Unemployment Insurance Advisory Council, it had grown to over forty members around the time of modernization and was not engaged with the modernization project.

Design in Minnesota

Minnesota’s online application was designed with common scenarios in mind. Rules-based routing populates relevant questionnaires for applicants, expediting fact-finding stages. The system automatically detects and flags issues that require further fact-finding and generates relevant questionnaires for the applicant. The design approach from DEED was to “meet claimants where they are” rather than having to chase them down for information later. DEED reviewed prior claims data to determine the decision trees and drop-down options in the application and questionnaires. For weekly work search questions, DEED consulted with an outside academic to identify which questions actually cut to the heart of what it means to “search for work.”

The online self-service options available to claimants were completely new, since no online access was available prior to the project. At the time of our interview, the online system had a forty-five-minute “time-out” for initial applications, with limited autosave functionality. Claimants and employers, or employer representatives, are able to file claims as well as appeals online. They can also pick their hearing date and time, request interpretation, add witnesses, and add representatives. However, while prior to the UITIP, parties could file a single appeal that covered several issues, the new online appeals system requires a separate appeal for every issue. The system does not permit a party to select multiple issues to be addressed in a single appeal. While DEED still attempts to “batch” many of these appeals on the back end, that process is not automated and there is no way for parties to mark multiple appeals as “related” to ensure batching.

All credibility determinations are made by DEED staff, and no overpayment determinations are made without an actual person involved. The backend functionality “pushes” flagged issues to adjudicators, with the oldest issue flagged as top priority, to help streamline claim processing. Still, the system primarily relies on the ability of claimants to answer detailed questionnaires, which were written at a high literacy level.

The two-stage design project included user testing. During the first phase, the agency assembled focus groups composed of employer customers and third-party administrators. These user groups were shown prototypes of the self-service system and asked for feedback. The second phase invited employers, third-party administrators (TPAs), and current UI applicants to participate in focus group discussions. Feedback from the focus groups helped the agency make improvements to website navigation and wording prior to the official launch.60

Stakeholder Feedback on Design in Minnesota

- Hours were limited. Focus group participants were frustrated by the website’s limited service hours. While most Internet users expect 24/7 access to online services, Minnesota’s online UI system is only available from 6:00 AM to 6:00 PM, Monday through Friday. Claimants explained that they found this timeframe inconvenient, especially when they were also actively looking for work.