In 2014, the Islamic State swept across large swaths of Iraq and Syria, soon emerging as the obligatory lede for every article about the Middle East and its history. Western commentators were quick to denounce the group’s radical theology and penchant for beheading. But they had little to say about its surprisingly mainstream take on the origin of modern Middle Eastern borders.

With the release of a propaganda video documenting the physical destruction of the Syrian–Iraqi border, then another titled “The End of Sykes–Picot,” the Islamic State added its voice to an ideologically diverse chorus placing the 1916 Sykes–Picot agreement at the root of all the region’s problems.1 The first video shows a bulldozer crashing through a sand berm, while a voiceover declares an end to the divisive and artificial national borders imposed by foreign oppressors. The second shows the demolition of a border checkpoint and promises more to come.

If no one particularly liked the Islamic State’s response to these borders, many shared its assessment of them. Despite their disagreements, commentators ranging from Jon Stewart to John Bolton, not to mention Joe Biden, also argued that the Middle East was a mess because it was divided into artificial countries by arbitrary lines in the sand.2 In an area still reeling from the consequences of Western imperialism, a secret World War I agreement between the British and French, as represented by the mustachioed Mark Sykes and the even-more-mustachioed François Georges-Picot, served as the perfect moment of original sin.

But the story that colonial borders are the source of all problems in the Middle East masks the true history behind the region’s constant conflicts. The world is full of examples of borders that cut across languages, cultures, and religions—creating countries that are perfectly peaceful. If many Middle Eastern states appear different—torn apart by conflicts along ethnoreligious lines—it is not because of the way their colonial and postcolonial regimes drew borders. Rather, it is because of the way those regimes tied citizenship rights to ethnic and religious identity. With more inclusive models of citizenship and stronger democratic norms, minorities would have less reason to fear being caught on the wrong side of political lines. Likewise, many of today’s Middle Eastern borders have proven so divisive because conflict has rendered them militarized and impassible. Democratic states at peace with their neighbors tend to have borders that are easy to cross, making life better for populations on both sides.

This report dives into archives and maps from the Ottoman period through the end of World War I to show that there was never any way to make Middle Eastern borders conform to the contours of ethnoreligious communities. Indeed, neatly segregated populations were no more a possibility in the Middle East than in any other region. Examining and understanding this history—and discarding the “bad borders” myth—is an important step toward realizing that inclusive citizenship remains the most reliable path to peace and stability. Fantasies of segregation, population transfer, and redrawn borders—whether the Islamic State’s or Donald Trump’s—will only ever contribute to more bloodshed and misery.

Drawing Borders, Making States

Not surprisingly, many people who criticized the Sykes–Picot borders also had a preferred alternative. If the region’s current configuration of states was made up, why not replace it with something better? Amidst the upheaval and violence of the Iraq war and the Arab Spring, a number of local leaders put forward, albeit less violently than the Islamic State, new political projects of their own. Meanwhile, Western publications took a newfound interest in imaginative remappings of the region. Would civil wars in Iraq and Syria end with the emergence of a Kurdistan, a Sunnistan, and—maybe we could have been more imaginative with the names—an Alewitestan?3

Over the subsequent years, a small army of academics gradually pushed back against the myth of Sykes–Picot.4 Some pointed out that the current borders of the Middle East bear at best an imperfect resemblance to the lines drawn by Sykes and Picot. Moreover, while the French and British clearly played a decisive role, they were not drawing new states on a blank canvas. Today’s borders also reflect the influence of some long-standing cultural and geographic regions, as well as the diplomatic and military efforts of actors on the ground. Historian Sam Dolbee has further noted that the process of cynically manipulative imperial border-drawing in the region didn’t actually begin with Europeans—it was also a feature of nineteenth-century Ottoman statecraft.5

Yet despite these efforts, elements of the myth live on. In popular discussion, there remains the lingering sense that Middle Eastern borders, and by extension the states they enclose, are somehow “artificial.” While not always made explicit, the implication is that this differentiates them from other more “real” states in places like Europe.

Middle Eastern borders were artificial, of course, but no more so than their European counterparts. If Winston Churchill supposedly drew the modern boundaries of Iraq with the stroke of a pen, he also drew the current border between France and Germany over the course of two world wars. There was no magic map that showed where the French people stopped and the Germans started—just a continent that finally got tired of fighting about it after a century or so. Blaming today’s ethno-political clashes on colonial borders tacitly accepts the logic of ethnonationalism, and accepts that segregating humans by identity is the best way to reduce or eliminate conflict. This assumption has served as the justification for partition, ethnic cleansing, and even genocide, in Europe and the Middle East alike.

Even academics who reject this logic and view all states as artificial are still susceptible to a slightly different version of the Sykes–Picot myth, focused on the critique of borders themselves. For these nostalgic historians, the tragedy is that Europeans, and the ideology of nationalism they brought with them, destroyed a once-united political, economic, and cultural space by dividing it up into modern states.6 In fact, the Western imperialists who created the modern Middle East were more attuned to the dangers of dividing societies than we might like to think. Rather than being reckless ideologues who carelessly cut up communities, they often worked to mitigate the disruption their new borders created.

Focusing too closely on where the French and British drew borders risks ignoring the more salient fact that they were drawing them in the first place. More often than not, the truly divisive aspects of colonial rule happened within borders. Moreover, the Sykes–Picot fixation confuses cause and effect. Not surprisingly, the Middle Eastern states that were strong enough to resist or mitigate European imperialism were also the ones that proved most successful in drawing their own borders and building more stable, prosperous societies. When we fail to recognize this, it becomes all too easy to imagine well-meaning foreign interventions as the solution to the malign ones of an earlier era.

Seen from today, the making of Middle Eastern borders is not a tidy morality play about the ideologically driven failures of our predecessors. Rather, it’s an excruciating and unsatisfying lesson in the impossibility of the whole endeavor. There’s no right way to draw borders, just a lot of bad ways, followed by the enduring question of what to do about them.

Put simply, the problem isn’t borders. It’s the political models that turn borders into impermeable barriers of ethnic, religious, and political exclusion.

Ottoman Origins

So, what did the map of the Middle East look like before World War I? It depends on which map you look at. The simplest ones just show everything that was under Ottoman control—a territory stretching from Istanbul down through Egypt and across to the Persian border—as one solid color.7 It was all, after all, Ottoman.

Some more detailed maps divided things according to the Ottoman government’s own administrative regions. The boundaries and significance of these vilayets changed substantially over time, but most were smaller than modern countries. Then, up until the nineteenth century, a lot of European maps divided the whole area into a confounding combination of territories based on a mix of geography, history, and ethnicity.

Source: Robert Wilkinson, “Turkey in Asia,” Wilkinson’s General Atlas of the World, Quarters, Empires, Kingdoms, States &c. (London, 1794), David Rumsey Map Collection, https://www.davidrumsey.com/luna/servlet/detail/RUMSEY~8~1~241776~5512732.

Consider this fairly typical British map from 1794, “Drawn from the most respectable Authorities.” It divides “Turkey in Asia” into Anatolia, Roum, Armenia or Turcomania, Karaman, Algezira, Kurdistan, Syria, and Irak Arabi. As names go, these are all over the place. Geographic regions like Syria sit alongside ethnic regions like Kurdistan, while others, like Irak Arabi, combine the two. Anatolia is an ancient Greek geographic term, referring to the rising sun. Roum refers to the historic presence of the Romans, just as Karaman refers to the historic territory of the Karaman dynasty. Algezira, meaning “island” in Arabic, is a geographic term for the island-like region between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. And as for “Armenia or Turcomania,” well, there were both Armenians and Turcomans living there.

Some of these terms would turn up again as the name of modern states, although usually covering a distinctly different territory. Others wouldn’t. Turcomania, sadly, is nowhere to be found today. So, while these maps suggest that regions like Iraq or Syria aren’t completely new, one would still be hard pressed to predict any modern borders by looking at them.

Subsequently, in the course of the nineteenth century, ideas about nationalism spread across the globe. As a result, political leaders and mapmakers took a newfound interest in pinning down people’s language, religion, and cultural identity. Broad geographic regions wouldn’t do anymore. It was now important to know who was Armenian, who was Turcoman, and which specific villages they each lived in.

An exhaustive academic literature catalogues what a catastrophe this whole endeavor turned into.8 Looking at maps from the time, though, one can get a pretty good sense of what was going to go wrong. The first problem was figuring out what categories to put people into. The second problem was matching these still-contested categories with any conceivable set of borders.

Just looking at the keys on nineteenth-century ethnographic maps, one can see how many different, completely contradictory ways individuals could be identified. Some cartographers, for example, focused on religious divides, consistently putting Christians and Muslims in separate categories. Others prioritized language, separating speakers of Greek, Turkish, and Arabic. When these categories overlapped, things were relatively simple. But often they didn’t. Was it better to make a country out of Muslims who spoke different languages or Arabs who practiced different religions? For many people, say Greek-speaking Muslims in Crete, or Turkish-speaking Christians in Karaman, the difference between these two approaches would come to define their future.

Was it better to make a country out of Muslims who spoke different languages or Arabs who practiced different religions? For many people, say Greek-speaking Muslims in Crete, or Turkish-speaking Christians in Karaman, the difference between these two approaches would come to define their future.

Making matters more complicated, many maps divided people based not only on religion or language—categories that are still all too familiar today—but also by lifestyle: nomadic versus settled. Some drew a distinction between “Turks,” who farmed or lived in cities, and “Turcomans” who travelled on horseback tending to their animals. Farther south, a similar divide sometimes appeared between “Syrians,” living along the coast, and “Arabs” or “Bedouins” living nomadically in the desert.

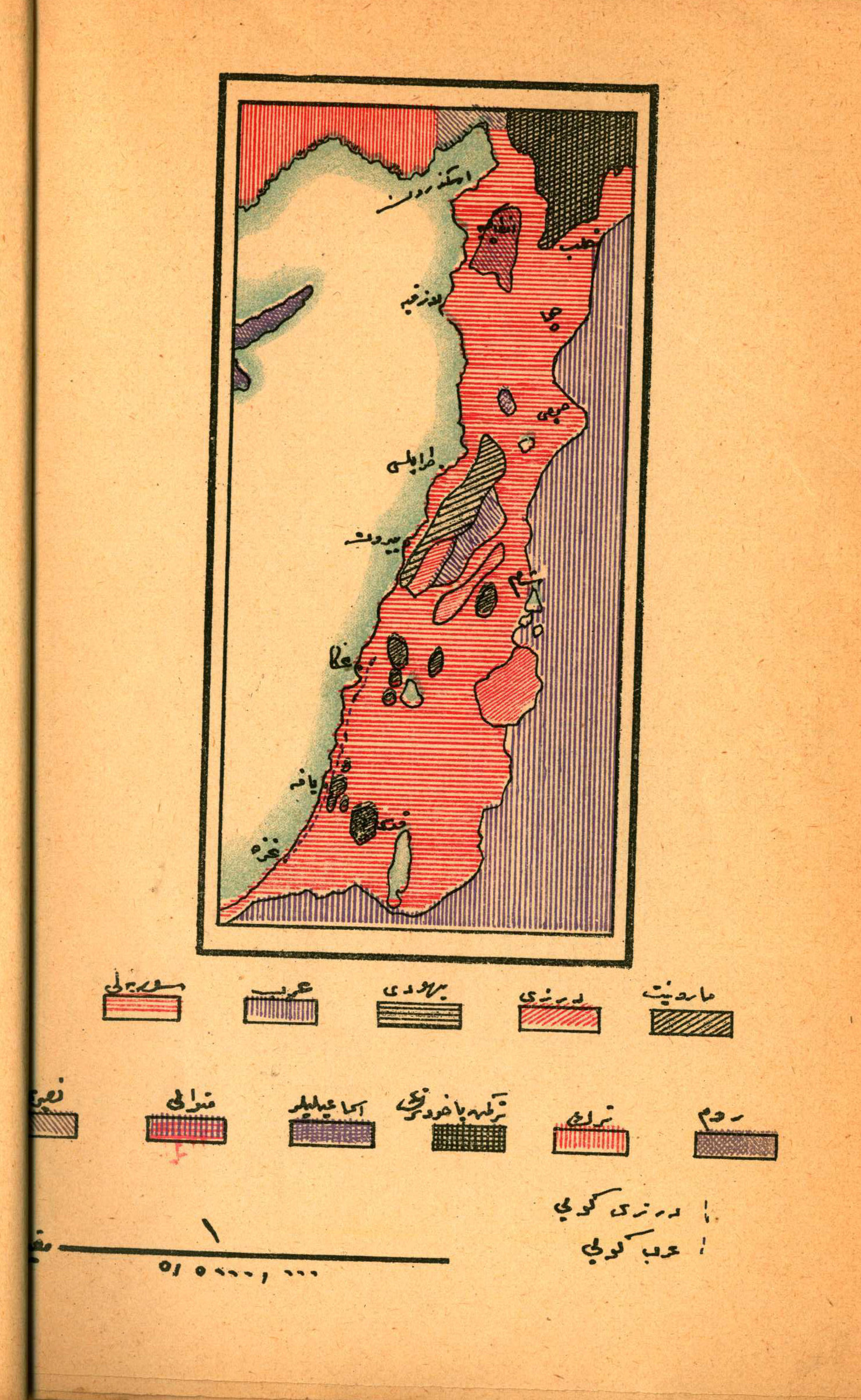

The bigger problem, though, was that whatever set of categories one chose, the results were never well suited to making coherent modern states. Consider this 1915 Ottoman map of the Levant.

https://farm6.staticflickr.com/5452/9881561535_8c0cc1feed_o.jpg.

Here, the range of different categories—mixing religion, sect, language, and lifestyle—is on full display, as well as the intricate breakdown of where people lived. Maps of the whole Middle East simply magnify the problem. Indeed, many also feature wide areas with overlapping colors where different groups of people lived side by side.

At the heart of the Sykes–Picot myth is the claim that when Europeans created new countries in the aftermath of the Ottomans’ defeat, they did so with arbitrary or cynically drawn borders that ignored the region’s real racial and religious divides. The implication is that if they’d been more attentive to these fault lines, they would have created more authentic, and, by extension, stable states. There was, to be clear, all sorts of cynicism in what actually happened. But there were also some individuals who recognized, and earnestly struggled to reconcile, the competing territorial demands of the region’s residents. In retrospect, it’s hard to imagine their proposals would have turned out any better.

The rest of this report explores how the map of the modern Middle East eventually emerged from the region’s complex nineteenth-century geography. Before moving on, though, feel free to pause for a minute, look at the map above, and come up with your own proposal.

A Multiplicity of Maps

Slowly during the course of the nineteenth century, then quickly during the course of World War I, the political collapse of the Ottoman Empire went from a remote possibility to a reality.9 As the empire’s survival grew increasingly unlikely, plans for what would replace it multiplied. The result is a story of conflicting, often wildly excessive ambitions clashing at a moment when everything seemed up for grabs. Some of these plans were more plausible than others, and some of them—not always the same ones—proved more successful. But almost all of them came with a map.

In 1915, on the eve of their amphibious invasion of Gallipoli, the British printed celebratory silk handkerchiefs showing their planned march to Constantinople.10 In one corner, the words “Well Done” were inscribed next to the New Zealand flag. In another, a Turkish flag with a Union Jack in its upper left quadrant appeared alongside the banner “Eclipse of the Star and Crescent.” There’s no evidence anyone had actually prepared a flag like this for a future Ottoman colony, but the general intent was clear.

As it happened, the victory handkerchiefs were premature. After eight months, Ottoman forces finally repulsed the Allied assault, saving Constantinople and indirectly launching Mel Gibson’s career. But British aspirations remained as lofty as ever. In the spring of 1916, they sought to soothe tensions with their French allies by reaching a secret agreement about the postwar division of the Middle East.

As seen on the infamous Sykes–Picot map, both countries awarded themselves direct control over areas in which they had particular strategic and economic interests.11 France had commercial ties to the Levant, and had long cultivated the region’s Christians. Britain intended to secure trade and communication routes to India through the Suez Canal and the Persian Gulf. To the extent that the Sykes–Picot plan made an attempt to account for the local ethnic, religious, or cultural groups, or their ideas about the future, it offered a vague promise to create one or several Arab states—under French and British influence, of course.

As with so many secret agreements, the real issue with Sykes–Picot was never the specifics that were agreed on but the nature of the agreement itself. In retrospect, the focus on how the British and French divided up the Middle East risks distracting from the more salient fact that they were colonizing it in the first place. Inevitably, the real impact of European colonialism would be felt after the war, when the British and French very publicly sought to overrule the wishes of the region’s inhabitants.

In retrospect, the focus on how the British and French divided up the Middle East risks distracting from the more salient fact that they were colonizing it in the first place.

It was only in 1920, after defeating the Ottoman Empire, that the European powers set about creating many of the states that exist today. In April, they met in San Remo to divide the area they had conquered during the war into the mandates of Syria, Mesopotamia, and Palestine. Later that summer, they met in Sevres, a Swiss town best known for its porcelain, to divide the remaining part of the Ottoman Empire. The arrangement they reached gave Britain, France, and Italy pieces of Ottoman territory, ceded part of the Aegean coast to Greece, and created an Armenian state in the northeast. Turks, for their part, were left with a small state around present-day Ankara.

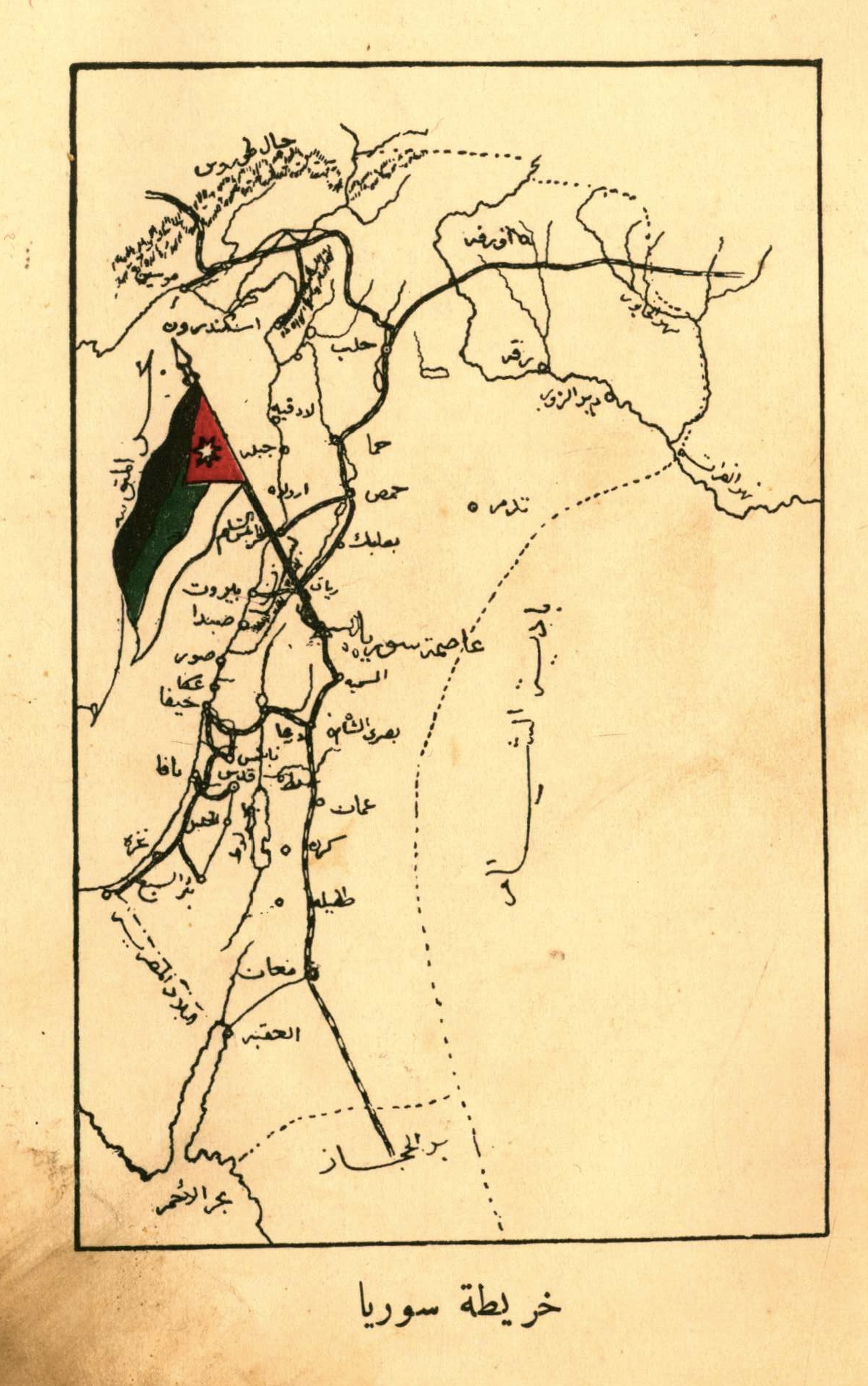

In fact, the British and French had organized these conferences in response to rival plans that were already being drawn up by those with a more direct stake in the matter.12 In the summer of 1919, representatives from across the Levant convened in Damascus and issued a proclamation calling for an independent constitutional monarchy. The monarch would be Prince Faisal, of Lawrence of Arabia fame, who had led the British-backed Arab revolt against the Ottoman Empire. And the borders, as seen below, would stretch from the Taurus Mountains in the north to the Khabur River in the east and down to the Gulf of Akaba.

Then, in early 1920, members of the last elected Ottoman parliament met east of Ankara and officially proclaimed their “National Pact.”13 In it, they declared that all Ottoman territories with a Turkish majority that were under the control of the Ottoman army at the end of World War I constituted “the homeland of the Turkish nation.” They further declared that territories with an Arab majority should be allowed to vote on whether they wanted to be a part of this homeland.

Resisting Colonization

The divergent fates of these two political projects lie at the heart of understanding the Sykes–Picot myth. In Turkey, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk reorganized the remnants of the Ottoman army and, after several years of desperate fighting, drove out the foreign armies seeking to enforce the Treaty of Sevres. By 1922, having defeated French, Greek, and Armenian forces, Atatürk’s forces threatened to march against the British, who were occupying Istanbul and the straits. The British backed down. After several months of negotiations, the result was the new Treaty of Lausanne, which recognized Turkish independence in almost all the territory claimed by the National Pact.

In Syria, by contrast, the plans of Faisal and the Syrian National Congress quickly fell afoul of French colonial ambitions.14 In late 1919, the British, honoring their agreement with the French, withdrew from the northern part of the Levant. Instead of accepting French authority, however, the congress in Damascus formally declared the Arab Kingdom of Syria, making Faisal king and appointing a government. The French rejected this, subsequently citing the mandate they had been awarded at San Remo. Damascus, in turn, rejected the San Remo agreement. Ultimately, the French resolved this impasse by issuing an ultimatum, then sending an army from Beirut to enforce it. The Arab Kingdom of Syria’s newly appointed minister of war, Yusuf al-Azma, led a heroic but ultimately futile effort to stop the French at the Battle of Maysalun in 1920. Al-Azma was killed in the fighting, and the French proceeded to dissolve the Arab Kingdom.

As this history shows, Europeans were certainly happy to impose their preferred borders whenever they could get away with it. But the failure of Sevres showed that sometimes they couldn’t. When European statesmen tried to redraw the map of Anatolia, their efforts were forcefully defeated. In the Middle East, by contrast, Europeans succeeded in imposing borders because they had the military power to prevail over the people resisting them.

In other words, the fixation on Sykes–Picot confuses the cause-and-effect relationship between European-drawn borders and Middle Eastern instability. The regions that ended up with borders imposed by Europe tended to be those already too weak or disorganized to successfully resist colonial occupation. Turkey didn’t become wealthier and more democratic than Syria or Iraq because it had the good fortune to get the right borders. Rather, the factors that enabled Turkey to defy European plans and draw its own borders—including an army and economic infrastructure inherited from the Ottoman Empire—were some of the same ones that enabled Turkey to build a strong, centralized, European-style nation-state.

The idea of Europeans drawing lines on an empty map also distracts from the extent to which local visions sometimes clashed, and the way these clashes helped the Europeans consolidate their rule. There was, for example, a sizable overlap between the borders claimed by the Turkish National Pact and those claimed by the Arab Kingdom—a wide swath along what is now the Turkish–Syrian border whose inhabitants spoke a mix of Turkish or Arabic.15 So long as both groups saw the French as the main obstacle to achieving their aims, this wasn’t a problem. At moments, leaders of the Turkish and Arab movements even expressed interest in cooperating with each other in the face of a common enemy. But the territorial dispute never disappeared. In the late 1930s, Turkey ultimately struck a deal with France to hand over the contested area of Alexandretta, which is now the Turkish province of Hatay. Turkish nationalists were ecstatic over the region’s “return” to the motherland, while Syrian nationalists were furious over its loss and the French betrayal.16 The result was a running source of Turkish–Syrian tension whose consequences are still playing out today.

But back to the 1920s. After abandoning Faisal to the French in Syria, the British decided to make him king of their new Mesopotamian mandate, where they had just suppressed a nationalist revolt. As part of efforts to consolidate Faisal’s rule, the mandate was renamed “Iraq,” a historic Arabic geographic term that largely corresponded with the Ottoman provinces of Baghdad and Basra. The outstanding question, though, was whether this new political entity should also include the Ottoman province of Mosul, which was simultaneously claimed by the Turkish government and a nascent Kurdish independence movement.

Here, Faisal, the British government, and the recent nationalist rebels were all on the same page. Not surprisingly, they all preferred the more expansive set borders for their new state. As described by historian Sarah Pursley, “nationalist poets in Baghdad and Basra waxed lyrical about Mosul as the ‘Jewel of Iraq.’” The prime minister “asserted that Mosul was the ‘head’ of the ‘body’ of the Iraqi nation,” and Faisal insisted it was “a life or death matter for our beloved country.”17 To secure Iraqi acquiescence to their rule, the British promised to help ensure that Iraq’s claim prevailed over Turkey when the matter was brought before the League of Nations. And where France ultimately disappointed the people of Syria by surrendering Hatay, Britain came through for Iraq.

And this, perhaps, is the ultimate irony of Sykes–Picot. Iraq has been repeatedly described as an artificial British creation, welding together a diverse group of Sunnis, Shia, and Kurds who wanted nothing to do with each other. Yet the British were never more popular than when they helped ensure that the Kurds in Mosul would be welded onto the rest of the country.

In Syria, by contrast, France did initially try to split the region into smaller statelets.18 The French created territories for the Alawites, the Druze, and the Turks, as well as two more centered around the cities of Damascus and Aleppo. Syrian nationalists correctly saw this as a cynical strategy of divide and conquer. In fact, Syrian resistance to this division was one of the sparks for the Great Revolt of 1925. In the words of an anti-French pamphlet published on the eve of the uprising, “The imperialists have stolen what is yours. They have laid hands on the very sources of your wealth and raised barriers and divided your indivisible homeland. They have separated the nation into religious sects and states. . . . To arms!”19 In the end, the French relented. While they defeated the rebellion and maintained their hold on Syria for another two decades, they eventually abandoned their plan for subdividing the region.

Of course, to the dismay of those who envisioned a unified Syrian homeland, one French-imposed division did prove more popular and enduring: Lebanon. Unlike the other states the French had proposed, Lebanon had a longer history of autonomy, going back to 1861. It also had a substantial population of Maronite Christians who did not want to be part of a larger Syrian state that was predominantly Muslim. Many Maronites welcomed the French mandate, and sought to use French intervention in the region to advance their own national goals. In cooperation with Maronite leaders, the French government created a Lebanese state that extended beyond the heavily Maronite areas of Mount Lebanon to include the Mediterranean coast and also the Beqaa Valley farther inland. This gave France’s Maronite allies a more viable territory, with ports to facilitate trade and a fertile region to grow grain. Yet these expanded borders also gave the new state a substantial non-Christian population. Their subsequent conflict with the Maronite-dominated political order would lead to the Lebanese Civil War.

Watching civil wars consume Iraq and Syria over the past two decades, some commentators suggested that partitioning these “artificial” countries into more “authentic” parts might help stabilize them. But no one was more resistant to these proposals than the leaders of Iraq and Syria. In 2017, the government of Baghdad acted decisively to crush a Kurdish declaration of independence. And in Syria, Bashar al-Assad’s successors appear just as committed as he was to violently maintaining a unified state. A century on, the real borders remain the ones that prevail through force of arms.

The King–Crane Conundrum

But was there a better way? What if instead of secret agreements, imperial plotting, and nationalist warfare, a group of enlightened, impartial observers could sit down and map out the best possible borders in consultation with everyone affected?

In 1919, President Woodrow Wilson wanted to try. Disgusted by the self-interested European diplomacy he saw at Versailles, Wilson dispatched a fact-finding commission to the Middle East.20 Its objective was to determine the true wishes of the region’s inhabitants and help implement Wilson’s vision of self-determination. The team was led by an Oberlin theologian named Henry King and a Chicago plumbing parts heir named Charles Crane, a pair who presumably had the requisite combination of Biblical knowledge and business acumen to understand the region. After spending three weeks interviewing religious and community leaders in Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, and southern Turkey, the two men and their assistants issued a lengthy report. It detailed the range of views they had heard and proposed the ideal territorial dispensation for the region.

Needless to say, the report was ignored. It was never released by the U.S. government, and the French and British moved ahead with their preferred plans at San Remo. Several years later, it was leaked to a U.S. magazine, which published it as a “suppressed official document.”21 The suggestion was that if American idealism had prevailed over European cynicism, the Middle East might have been saved.

Read today, the King–Crane report is still a striking document—though less for what it reveals about the Middle East as it might have been than as an illustration of the fundamental dilemmas involved in drawing, or not drawing, borders.22 Indeed, the report consistently concluded that people could best live together through complicated legal arrangements that prefigure more recent proposals for intercommunal coexistence.

Among other things, the authors concluded that dividing Iraq into ethnic enclaves was too absurd to merit discussion. Greeks and Turks could share one country because the “two races supplement each other.” The Muslims and Christians of Syria needed to learn to “get on together in some fashion” because “the whole lesson of modern social consciousness points to the necessity of understanding ‘the other half,’ as it can be understood only by close and living relations.”

But the commissioners also realized that simply lumping diverse ethnic or religious groups together in larger states could lead to bloody results. Their report proposed all sorts of ideas for tiered, overlapping mandates or binational federated states, ultimately endorsing a vision that could be considered either pre- or post-national, depending on one’s perspective. In addition to outlining several autonomous regions, they proposed that Constantinople become an international territory administered by the League of Nations, since “no one nation can be equal to the task” of controlling the city and its surrounding straits. The authors had been tasked with drawing borders, but when confronted by the dilemmas of implementing self-determination, they developed a more fluid approach to nationhood and identity.

“No doubt the quick mechanical solution of the problem of difficult relations is to split the people up into little independent fragments,” King and Crane wrote. “But to attempt complete separation only accentuates the differences and increases the antagonism.”

Disagreement among the region’s residents about their own future certainly helped the commission reach this conclusion. The commissioners traveled from city to city accepting petitions and taking testimony, compiling a rare record of Arab popular opinion from the period. This early polling exercise captured a wide range of views—some overlapping, some irreconcilable.

Roughly 80 percent of those interviewed favored the establishment of a “United Syria.” But rather than settling the question, this forced the commission to wrestle with what should happen to minorities. Many of the Christians living in this hypothetical future state, particularly those in the Mount Lebanon region, rejected “United Syria” in favor of an “Independent Greater Lebanon.”

The commissioners’ proposed solution was to grant Lebanon “a sufficient measure of local autonomy” so as not to “diminish the security of [its] inhabitants.” But in rejecting complete independence, they seemed to challenge the fundamental logic of self-determination: “Lebanon would be in a position to exert a stronger and more helpful influence if she were within the Syrian state, feeling its problems and needs and sharing all its life, instead of outside it, absorbed simply in her own narrow concerns.”

The broader conclusion King and Crane reached about human affairs was similarly at odds with the principle of self-determination, anticipating today’s ongoing debates about where the Middle East’s borders really belong. “No doubt the quick mechanical solution of the problem of difficult relations is to split the people up into little independent fragments,” they wrote. “But in general, to attempt complete separation only accentuates the differences and increases the antagonism.” Even when they conceded exceptions—for instance, in the “imperative and inevitable” separation of the Turks and Armenians given the Turks’ “terrible massacres” and “cruelties horrible beyond description”—King, Crane, and their team nonetheless concluded that “a separation . . . involves very difficult problems” and could easily backfire.23

One way King and Crane tried to square the circle was suggesting that some benevolent foreign power—perhaps the United States—oversee these new arrangements. At key points, the King–Crane proposal relied on the creation of European or American mandates to fudge different degrees of sovereignty and ensure minority rights in multinational states. Placing different mandates under the same mandatory power became an easy way to separate peoples while maintaining an administrative link between them: Syria and Mesopotamia, for instance, could both be under British supervision, while Turkey and Armenia could both be overseen by the United States.

Here, their thinking quickly came to resemble that of the cynical imperialists they sought to supplement. France and Britain repeatedly justified their rule in the region by claiming it was necessary to manage national differences and protect minority rights. Indeed, part of the reason the British and French felt so comfortable drawing “arbitrary” borders was that they believed they would remain in a position to manage relations across them. It was, in a sense, a more condescending, cynical, and self-serving version of the logic behind the League of Nations itself. As multinational states like the Austro-Hungarian Empire were divided into smaller national units, contemporary observers saw an increased need for supranational bodies to oversee relations between them.

Nomads, No Problem

Looking at how the King–Crane Commission wrestled with the concept of self-determination helps shed light on another version of the Sykes–Picot myth, one that remains popular among historians in particular. When the Islamic State released its video declaring the end of Sykes–Picot, few people realized that the border fortifications they so enthusiastically bulldozed were likely just a few decades old. In fact, the Iraqi–Syrian border was only delimited by a League of Nations commission in 1932, and it remained open for nomads to cross relatively freely until Iraqi–Syrian relations turned hostile in the 1980s.

Many liberal observers, from academics to reporters and memoirists, have all come to see the Middle East’s post-Ottoman borders as a particularly ugly embodiment of the way colonialism, nationalism, and the twentieth-century state all worked together to dismember a once-coherent space.24 Preexisting social ties were severed, trade networks were dismantled, and families were torn apart, all in the name of modernizing ideologies that refused to recognize the region’s interconnected reality. As a result, these new lines have come to symbolize the blind arrogance of those who reordered the region with so little regard for the lives they would ruin.

But it would be a mistake to assume that these borders sprung fully formed from the heads of the colonial officials and nationalist leaders who drew them, with barbed wire, checkpoints, and minefields inevitably following pens across the map. Moreover, it would be a mistake to assume that even in the heyday of nationalist thinking, politicians and diplomats were oblivious to the limitations of their own worldviews.

It is always tempting to blame today’s problems on the ideologically driven failure of our predecessors to anticipate them. The more damning possibility is that earlier generations of leaders or thinkers anticipated the challenges they faced quite clearly but still failed to find a lasting solution. Recognizing this doesn’t absolve our predecessors, but it can help us avoid their mistakes.

To a surprising extent, the political regimes that built the new borders of the Middle East after World War I acknowledged and tried to mitigate, if only for their own cynical reasons, the potential for disruption. In the 1920s and 1930s, many of the region’s borders were considerably more open than they are now. It was not merely the creation of borders that proved disruptive but, more crucially, the political tensions between governments on both sides that eventually led to their closure.

Consistently, borders drawn in the immediate aftermath of World War I took on a life of their own later in the twentieth century. Most of these lines were initially intended to be quite permeable. But political and military disputes gave them the fortified, disruptive character we associate with them today. Bad neighbors, it seems, make bad border regimes, and bad border regimes disrupt societies.

Among other things, the text of the Sykes–Picot agreement contained several clauses aimed at minimizing the impact of any new borders it created. Maintaining preexisting networks—of trade, at least—was important for imperial interests.25 Sykes and Picot agreed, for example, “that Alexandretta shall be a free port as regards the trade of the British Empire.” France was to be given similar rights in Haifa and, to further facilitate trade, there would “be no interior customs barriers between any of the above-mentioned areas.”

The League’s final report reveals the extent to which the diplomats who embodied the modern nation-state system also believed borders should be porous.

When the League of Nations was called on to adjudicate the dispute between Britain, Iraq, and Turkey over Mosul, it sent a commission to investigate the situation on the ground.26 The League’s final report helps reveal the extent to which the diplomats who embodied the modern nation-state system also believed borders could and should be porous. In making their cases to the League, both Britain and Turkey insisted that if the new Iraqi–Turkish border was drawn in the wrong place it would cause deep social and economic disruption. But if it was drawn in the right place, they insisted, these disruptions would be minimal and could be addressed with an attentive and responsible border regime.

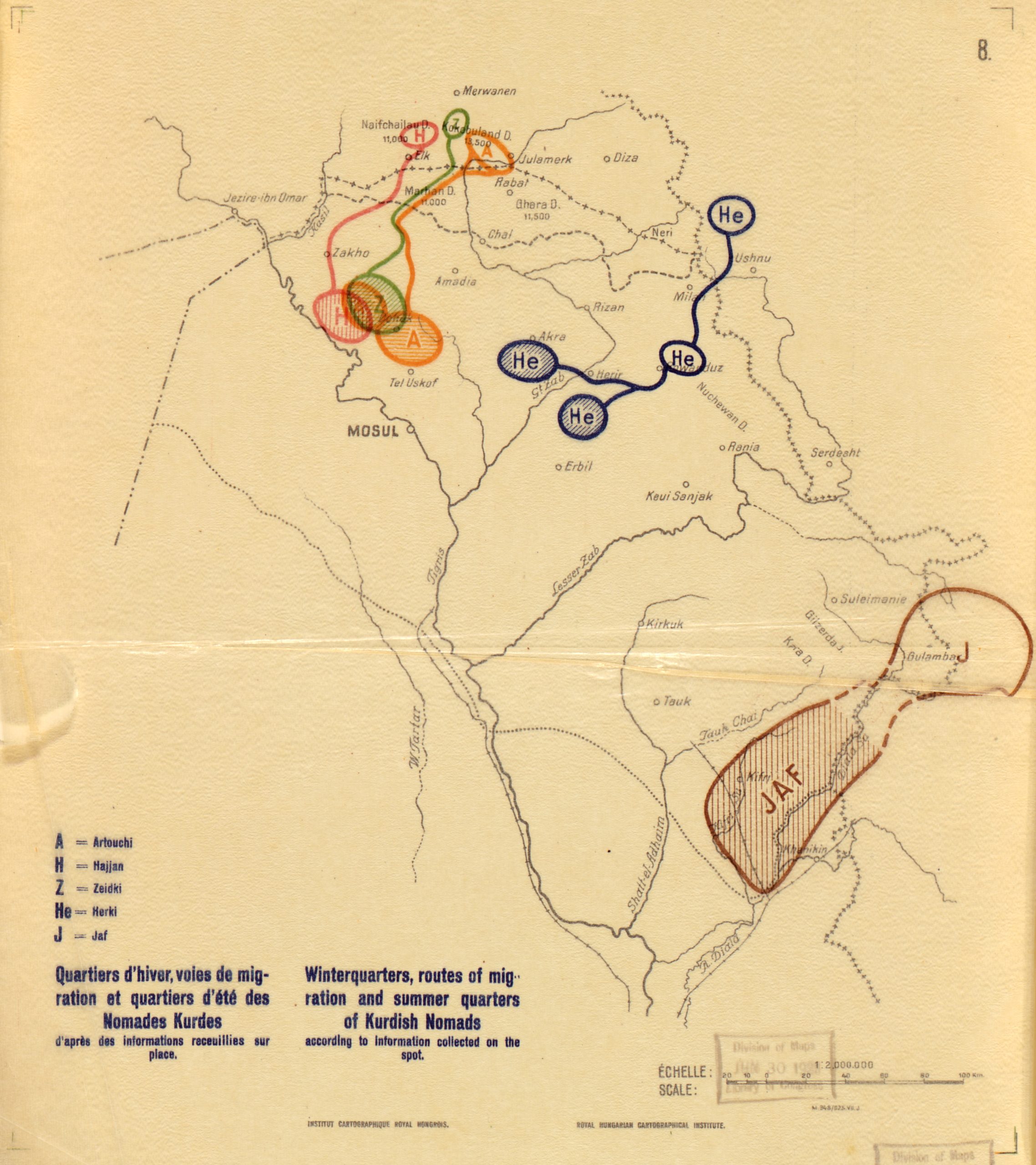

The League, for its part, seemed to think that whoever got Mosul and wherever the borders were drawn, the consequences would be manageable. As evidence, the League’s decision first cited an agreement already in place for the Persian frontier stipulating that “Turkish tribes which are accustomed to pass the summer in these valleys at the source of the Gadyr and Lavene will continue to enjoy the use of these pastures as heretofore.” (A later League report on Iraq and Syria also cites a seventeenth-century agreement between Norway and Sweden regarding nomadic migration in Lapland, with the caveat that camels and reindeer were somewhat different beasts.)27

Map of nomadic migration routes in northern Iraq prepared for the League of Nations. Source: “Winterquarters [sic], routes of migration, and summer quarters of Kurdish nomads” in “Question de la frontière entre la Turquie et l’Irak: rapport présenté au conseil par la commission constituée en vertu de la résolution du 30 septembre 1924,” Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/resource/g7611fm.gct00117/?sp=7&r=-0.664,-0.03,2.329,1.181,0.

After mapping the regular migration routes of the region’s nomads, the League concluded that “the statements of the British Government regarding the difficulty of tracing a frontier across territory over which the Bedouin roam in search of pasture is rather exaggerated.” Why? Because the British government’s own reports on Iraq showed that it had been possible to do so successfully “even on the Iraq–Syrian frontier.” The League was equally optimistic that provisions could be made to maintain trade ties wherever the border was drawn. “If the disputed territory is assigned to Iraq,” the report argued, “its inhabitants should be given full freedom of trade with Turkey and Syria.” To make this possible, “facilities should be afforded to the Turkish frontier towns to use the Mosul route for exporting their produce and importing manufactured articles.”

Even more telling is that, when it came to both trade and nomadic migration, the League assumed that political forces, not borders, would be the main factor in transforming traditional patterns of life. Forcible resettlement of nomads by both the Turkish and Iraqi states, they suggested, would curtail migration, while the construction of new railways and roads would transform economic patterns in the region. In other words, other aspects of the modern state would prove more disruptive than the borders that came with them.

In fact, when European imperial powers drew borders in the region, they consistently included provisions to accommodate the web of economic and social relationships these new lines would cut across. As Robert Fletcher concludes in his study of interwar borders, “Freedom of grazing and nomadic migration was written into all major boundary agreements in the 1920s.” Moreover, he argues, “These terms were assiduously observed by local frontier officials, even to the point of risking conflict with demands from the center.”28

The language in many of these agreements was standard and relatively expansive. The 1926 Anglo–French “good neighbor” agreement, for example, states:

All the inhabitants, whether settled or semi-nomadic, of both territories who at the date of the signature of this agreement enjoy grazing, watering or cultivation rights, or own land on the one or the other side of the frontier, shall continue to exercise their rights as in the past. They shall be entitled, for this purpose, to cross the frontier freely and without a passport and to transport, from one side to the other of the frontier, their animals and the natural increase thereof, their tools, their vehicles whatever the mode of traction, their implements, seeds and products of the soil or subsoil of their lands, without paying any customs duties or any dues for grazing or watering or any other tax on account of passing the frontier and entering the neighboring territory.29

As to how these agreements played out, it seems that, across the British–French frontier that divided Syria and Lebanon from Palestine, the impact of the new border was initially quite modest. One historian writes that “travel documents could be obtained at minimal cost from French administrators,” but “people mostly continued to cross . . . without papers.”30 Another historian describes Zionists freely crossing the border between French and British mandates in order to hike Mount Hermon.31 As of 1941, “these trips did not require cross border permits because the border was wide open and they never met a Lebanese or Syrian policeman.” Sometimes even the nominal requirement for documents was waived, such as with a provision declaring that “pilgrims making the annual pilgrimage to the Nabi Yusha marabout at the end of Ramadan shall be exempt from formalities of a passport or laissez-passer.”32

Subsequently, a series of political developments proved decisive in bringing this once-open border to a close. In 1938, the British built a fence to stop gunrunners, following the outbreak of the Arab revolt. Then, in 1941, they deployed the Transjordan Frontier Force to stop Jewish immigration to Palestine. Finally, in 1948, two and a half decades after its demarcation, the border closed more conclusively, taking on the impassable and militarized character it maintained ever since.33

The Turkish–Syrian border experienced a similar transformation.34 At first, it was relatively open until the intensifying conflict over Hatay caused both sides to gradually impose new restrictions. The initial agreement governing the Syrian–Turkish border included a host of clauses like those cited above allowing locals to cross. Moreover, a Turkish train line extending east to the city of Nusaybin crossed the border at several points, an arrangement whose legal and logistical challenges Ankara found relatively minor in comparison with the track’s technical limitations. But, in the 1930s, the French set up new border controls to try to prevent the infiltration of Turkish guerrillas seeking to wrest control of the province. Then, after annexing Hatay in 1938, the Turkish government imposed new tariffs and transport restrictions as part of a deliberate effort to sever the region’s ties with Syria and incorporate it into Turkey.

As the case of Hatay shows most clearly, it was often battles over borders, rather than the borders themselves, that damaged the lives of those living along them. Trying to redraw these lines all too often ends up compounding the damage they’ve done. The alternative is for states to change their approach to them.

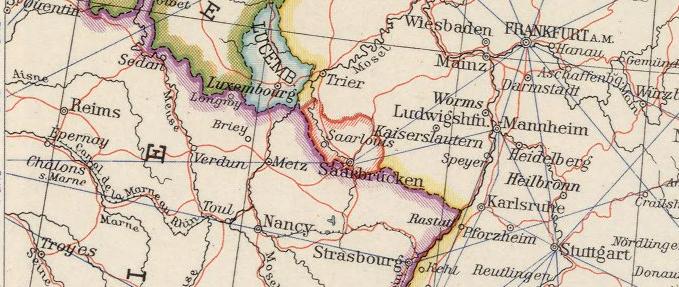

Meanwhile in Europe

Now might be as good a time as any to take a look at what was going on in Europe during the last century or two. Europe, of course, stands as the unspoken reference point in all discussions about Middle Eastern instability: the continent that got its borders right. Rather than the straight lines that mark off the Middle East, Europe’s borders look just squiggly enough, supposedly following natural features that conveniently correspond with the identities of the inhabitants.

Satirist Karl Sharro captured the difference nicely in a parody map that envisions Europeans drawing the borders of Europe the way they did in the Middle East.35 In his rendering, a series of straight lines cuts across the continent, chopping it into truncated geometric regions like the small, square Republic of London and the vaguely hexagonal Great Bavaria.

But you don’t have to delve very far back into European history before the contrast implied by all this cartography begins to break down. To see why, just dig up one of the old ethnographic maps that claimed to show Europe’s ethnic, racial, or linguistic geography. Then, imagine using it as a basis for modern-day borders. The results, as seen below, are far more reminiscent of Sharro’s parody map than the one we know today.

To start, ethnographers had differing ideas on how to parse even some of Europe’s most well-established states. Language learners could appreciate the appeal of lumping France, Italy, and Spain together into one giant kingdom, and the resulting World Cup team would certainly be formidable. Some maps, however, influenced by a range of outdated racial concepts, would also have divided France itself, minimizing, if nothing else, the number of cheeses Charles de Gaulle had to deal with.36

And then, whichever map you use, you get way too much Germany. Even by conservative estimates, large parts of Poland, Belgium, and the Czech Republic—not to mention all of Austria and the Netherlands—get swallowed up in some sort of greater German state. Suddenly, Europe’s real borders start looking an awful lot like the ones Europe fought several wars to prevent.

Things only get worse when you move farther east. The idea of joining together Serbs, Croats, and Slovenians into a South Slavic or “Yugoslav” state proved problematic enough in reality. Many ethnographic maps would have thrown in Bulgaria as well. Most of them would also have implicitly endorsed Putin’s imperialist aggression against Ukraine under an expansive definition of Russian national identity.

The irony, of course, is that Europe, past and present, is nothing if not a cautionary tale about the dangers of trying to make states correspond too closely with simplistic notions of national identity. Consider—very briefly—the Saar. As territories along the Franco–German border that don’t seem that exciting anymore but once caused a disproportionate amount of international conflict go, the Saar Basin is slightly more obscure than most. The Rhineland and the Ruhr, not to mention Alsace and Lorraine, get all the attention. But on interwar maps of Europe, the Territory of the Saar Basin stood out as a strange cartographic blip, one that mapmakers seemed slightly unsure what to do with.

Their confusion was understandable. Following the Treaty of Versailles, a small piece of the Saar River Valley, containing the towns of Saarlouis and Saarbrücken, was awarded to France as a League of Nations mandate.37 In this case, control would be in the hands of an international, five-person governing commission, and the territory would be allowed to vote on its final political status after fifteen years. In the meantime, the French government could exploit the region’s coal mines, thereby securing compensation for those in northern France destroyed by the retreating Germans.

As with the mandates of Iraq and Syria, this arrangement was an awkward attempt to reconcile political occupation with a nominal commitment to self-determination. In the words of one French author, “We must have the coal, and we must find some arrangement to get it without annexing the population.” Or more simply: “If we could only get the coal without the people.”38 The coal may have been fine with this arrangement. But, as in the Middle East, the local population of the Saar Basin was not particularly thrilled about French rule. And their cause was quickly championed by German nationalists who were already angry about the postwar settlement.

Among the many people vexed by this development was one Charles Homer Haskins.39 A medieval historian who had won Woodrow Wilson’s admiration at Johns Hopkins, Haskins was invited to serve as one of the president’s three principal advisors at Versailles. Where Henry King brought a theological knowledge of the Middle East, Haskins’ knowledge of Europe was reflected in such articles as “The Sicilian Translators of the Twelfth Century” and “Further Notes on Sicilian Translations of the Twelfth Century.” Armed with this knowledge, Haskins, like King, struggled to find a political arrangement that would keep everyone as happy as possible.

The result was the Saar Mandate, and it did not keep people happy. As the arrangement faced increasing criticism in the coming years, Haskins came to its defense. In a series of articles for Foreign Affairs, he explained the necessity of the mandate and praised the French administration. In a book titled Some Problems of the Peace Conference, he gamely reminded unhappy German residents of the Saar that “their participation in self-government is much greater than that of the inhabitants of the District of Columbia!” More optimistically, he noted that the Saar’s position was so enviable that some observers even predicted its residents would vote to maintain their anomalous mandate status. At which point, in the scanned University of Michigan copy of Haskins’ treatise available on Google Books, an anonymous reader has scrawled “Not So!!” then “Heil Hitler,” and then, for good measure, a swastika.40

As it turned out, the margin Nazi was more prescient than Haskins about how citizens of the Saar would vote: 90 percent ultimately opted for reunification with Germany in a 1935 plebiscite. But this triumph proved short-lived. A decade later, they were back under French control again. With the Allies occupying all of Germany after World War II, the French set up a new administration, this time called the Saar Protectorate. Amidst broader uncertainty over Germany’s postwar fate, the Saar Protectorate never featured as prominently on the map as its interwar predecessor. But it did briefly get its own soccer team. Saarland players racked up one international win against Norway before merging with West Germany in 1956.

What is the lesson of the Saar Basin’s short mid-century history? Maybe it’s that no matter how tiny a sliver of Germany you take, it can still field a competitive soccer squad. Or maybe it’s that no one likes mandates. And border drawing is an ugly business, whether in Europe or the Middle East.

From the horrors of World War II to the expulsion of twelve million Germans from Eastern Europe in its aftermath, state-making in Europe was anything but natural.

Indeed, as both the map above and the story of the Saar show, the process of making states in modern Europe was never simply a matter of drawing the right lines to match the preexisting ethnographic divisions. So why is it that today, most people in France identify as French rather than Breton or Provençal or German? Why is it that most people in Romania identify as Romanian rather than German or Hungarian?

To the extent that there is a stronger correspondence between borders and identity in Europe than in other parts of the world, it was the product of both brutally exclusionary and liberally inclusive policies over the last century. European states owe their current homogeneity, such as it is, to a mix of voluntary assimilation, forced assimilation, ethnic cleansing, and genocide. On the positive side, many of these states inculcated identification and loyalty by distributing rights and services to their citizens and allowing them to participate in democratic self-rule. On the coercive side, an earlier generation of teachers and military officers also beat recalcitrant students and conscripts who refused to speak their national tongue in the classroom or the barracks. And then there were the murders and deportations. From the horrors of World War II to the expulsion of twelve million Germans from Eastern Europe in its aftermath, state-making in Europe was anything but natural.

What’s more, at the very moment Europeans settled on the borders that exist today, they set about dismantling them. The creation of the European Union was, in a sense, Europe’s effort to apply at home the same observations that the King–Crane Commission and the League of Nations Mosul investigators had already reached in the Middle East. Borders work best when they’re porous. And more flexible alternatives to the nation-state system are needed to help people “get on together in some fashion.”

Much as many in the Middle East wax nostalgic for an earlier time when one could board a bus from Haifa to Beirut, postwar European integration was bolstered by nostalgia for the period of interconnectedness that existed before World War I. This was Stefan Zweig’s era of “no permits, no visas, nothing to give you trouble.”41 No one wanted to resurrect Zweig’s homeland, the Austro-Hungarian empire, just as few in the Middle East want to resurrect Ottoman or British rule. But the pre-national era was still offered as a romantic inspiration for constructing a post-national one. This was the context in which Otto von Habsburg, the last crown prince of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, could, in the early 2000s, end his career as the most senior member of the European Parliament.

So What Did Go Wrong?

Having come this far, it would be tempting to conclude that it wasn’t bad borders that destabilized the Middle East, and leave it at that. Maybe point out for good measure that things aren’t looking too hot for European democracies right now, either. But that seems too easy. Comparatively, Europe has had a very good run over the last half century, and still continues to. Whatever is happening in Belgium right now—and this author doesn’t claim to know—the country hasn’t descended into civil war yet. With this in mind, it’s worth looking beyond borders to understand why some states in the Middle East may have proved more stable than others.

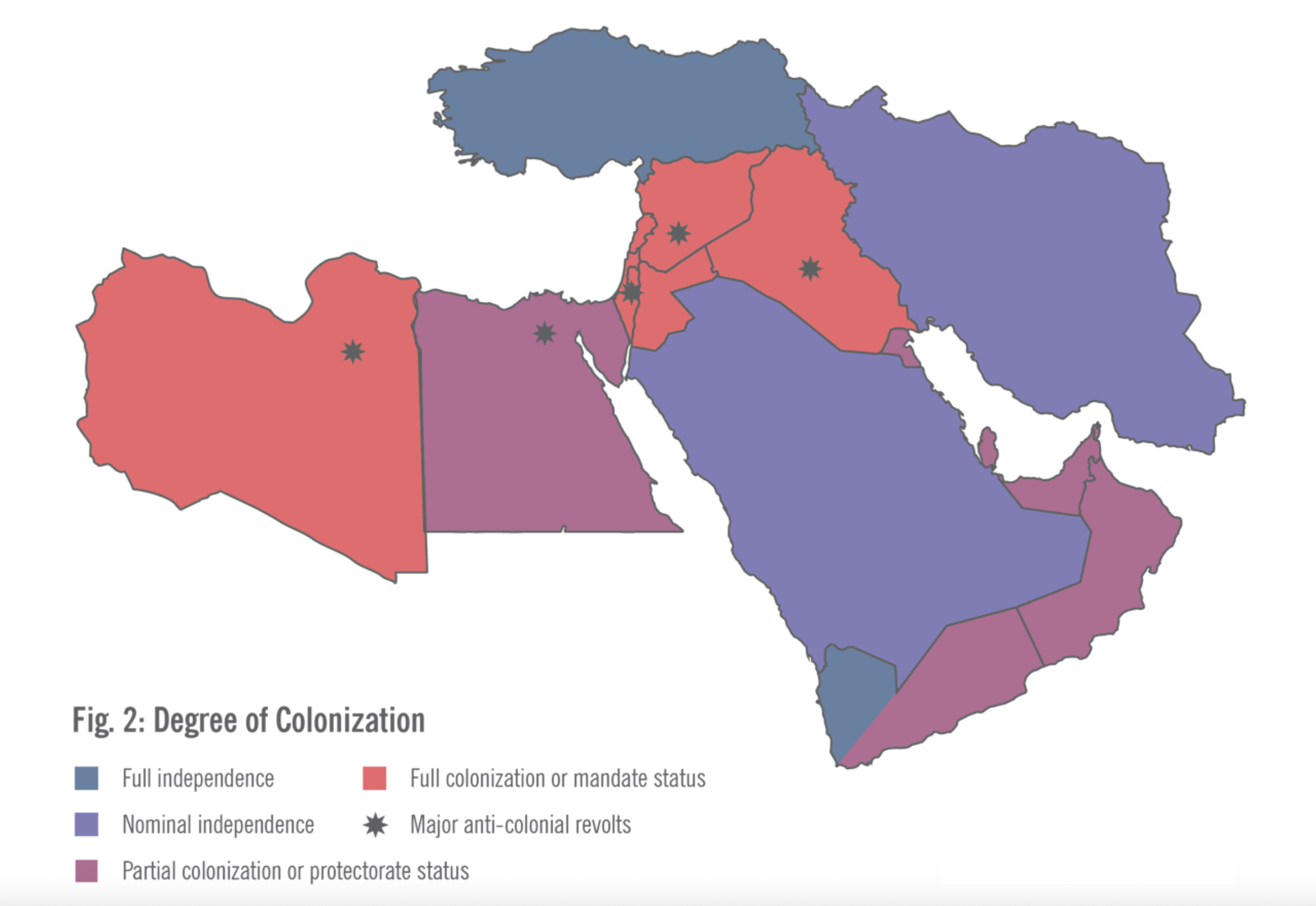

The story certainly seems to start with the fact that the political entities that existed before the start of the twentieth century have proved relatively more stable. It’s not that they were more real. Rather, as this report has shown, they had the resources to draw their own borders and escape the worst consequences of colonialism.

Turkey, Egypt, Iran, and, in a different way, the ruling dynasties of Kuwait, Qatar, Bahrain, Oman, and the United Arab Emirates, all, in one form or another, trace their current political structures back to the late nineteenth century. Consequently, they were more likely to have the resources to maintain some independence in the face of European imperialism, or at least negotiate a less disruptive form of colonial rule. Whatever problems these countries face today, they have been spared the degree of truly catastrophic violence that has recently beset Syria, Iraq, Libya, and Yemen.

Turkey, which inherited the strongest nineteenth-century state, was most successful in escaping colonialism. Egypt, which achieved de facto independence at the start of the nineteenth century, was a British protectorate for several decades. But it also became the first country in the Middle East to achieve nominal independence in 1922, under the same dynasty that had broken free from the Ottomans more than a century earlier. Iran, meanwhile, was divided into informal spheres of influence by the British and Russians in the late nineteenth century. But it avoided formal colonization and initially kept the Qajar dynasty (1789–1925) in power.

As a result, both Egypt and Iran had ruling institutions predating European colonial influence that subsequently remained in place. In both countries, local politics were, to a greater degree than elsewhere, allowed to continue, subject to external constraint and coercion. Meanwhile, the far smaller dynasties of the Persian Gulf became protectorates of the British Empire on mutually beneficial terms. This created symbiotic relationships in which the British provided military support and trade opportunities that left these regimes stronger and wealthier than they were before.

In contrast to these preexisting entities, countries such as Syria, Iraq, Libya, and Lebanon came into being in the early twentieth century complete with new borders and hastily formed governments set up by their colonial rulers. From the outset, these governments lacked the legitimacy of those indigenous rulers, who, however unwillingly, had come under the influence of colonial powers. Unsurprisingly, all of these countries beside Lebanon soon experienced widespread and violent anti-colonial rebellions.

The countries that came into being as mandates did not have the opportunity to shape their own borders. But, more importantly, imperial rule also prevented them from shaping their own populations in the good and bad ways European states had.

The mandate system proved an obstacle to ethnic cleansing—whether of the violent or legally orchestrated variety—as well as the creation of democratic political structures that could build an inclusive sense of identity among diverse populations. Instead, in trying to create and dominate new states with the minimum amount of money and manpower, colonial governments set up power structures that instrumentalized internal divisions. This enabled them to maintain the façade of an inclusive polity without building political institutions or shared identities that could endure after colonial rule ended. As a result, the experience of these mandates after their creation and within their borders is key to understanding the instability they continue to experience today.

Brutal violence also accompanied the formation of many other states that ultimately proved more cohesive. The difference is in how this violence intersected with other aspects of state-building.

The mandate-era states of Iraq and Syria were forged and maintained with violence.42 But in this they were not necessarily unique. Brutal violence also accompanied the formation of many other states that ultimately proved more cohesive. The difference is in how this violence intersected with other aspects of state-building. In the mandate context, the violence was implemented in a way that exacerbated preexisting divisions instead of suppressing or eliminating them.

Britain, for example, put down Iraq’s 1920 revolt with the help of extensive airpower, then dropped poison gas on Kurdish tribes who continued resisting. Syria’s 1925 revolt ended with French artillery shelling Damascus. But in both cases, colonial powers also triumphed by recruiting local allies along ethnic or tribal lines to fight on their side against the rebels. Not surprisingly, then, the result of these revolts, even when they were defeated, was to deepen social divisions within these countries and strip governing institutions of their legitimacy at the moment of their inception.

In Syria, for example, colonial authority made a concerted effort to recruit minorities, specifically Christians and Alawites, into the army. This did not, as the French officials had hoped, prevent the emergence of Arab or Syrian nationalism among these communities. But it did contribute to the continuing political relevance of Alawite identity within the state. Similarly, in Iraq, the British adopted a “tribal policy” that depended on the threat of aerial bombardment to win compliance from tribal leaders who were beyond Baghdad’s authority. Yet this undermined the legitimacy of the tribal leaders who cooperated with Britain, intensifying the internal divisions within tribes and between the tribes and the state.

At the same time, the mandates’ reliance on divisive forms of rule was not the whole story. Mandate authorities also prevented the kind of killing and deportation that countries like Turkey and Israel used to homogenize their populations in 1915, 1923, and 1948. The Armenian genocide, the Turkish–Greek population exchange, and the Nakba all reflect the kind of violent homogenization that occurred in European states, as well. If other Middle Eastern countries seem less cohesive than their European counterparts, part of the reason is that they experienced less ethnic cleansing early on.

A Winding Path Dependency

In retrospect, there is a clear path dependency in the ensuing history. The factors that left some states less stable at the outset of the century only created more problems with the passage of time. The bitter irony in both Syria and Iraq was that after achieving independence, both countries embarked on nation-building campaigns using the full coercive power of the state. In both cases, repressive Ba’athist regimes compensated for their late start and internal fissures by resorting to unusually draconian methods to preserve and enforce national unity. But in both cases, these methods proved counterproductive.

Observers have often noted that the Middle East’s long-standing monarchies appear significantly more stable than its republics. But this reading mistakes cause for effect. A century or so ago, every country in the region, except the French mandates of Syria and Lebanon, had a king. Libya and Iraq, along with Iran, Egypt, and Turkey, were all originally monarchies, at least until these monarchies proved too unstable to survive. In Turkey, Atatürk removed the sultan in 1922. In Egypt, the Free Officers overthrew King Faruq in 1952. In Iraq, Faisal’s family maintained its throne with British support until 1958, when Faisal’s grandson was overthrown and executed in a military coup. The Libyan monarchy fell to Muammar Qaddafi in 1969 and the shah of Iran fell a decade later. Perhaps, then, it’s more accurate to say that in unstable states the monarchies fell, while those in more stable countries were the only ones to survive.

Moreover, in the 1940s and 1950s, the endurance of monarchies was inseparable from Cold War politics.43 While American officials often had deep reservations about British colonialism, they quickly concluded that maintaining British influence was preferable to the risk of Soviet infiltration. As a result, pro-British rulers like the shah of Iran, Faisal II in Iraq, and King Farouk in Egypt became crucial elements of Anglo-American efforts to contain Soviet influence in the region.

When their monarchies fell, these countries moved away from their alliances with the West. Libya, too, followed a similar pattern after the fall of King Idris, who, despite his impeccable anti-colonial credentials, was tainted by his pro-Western political orientation. In Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and the Gulf, by contrast, pro-Western monarchies survived and kept their countries in the Western orbit throughout the Cold War.

In the ensuing decades, the countries that ended up on the Western side in the Cold War have largely fared better than those which sided with the Soviets. Why? First, the political challenges some states faced may have left them predisposed to both instability and seeking support from Moscow. At the outset of the Cold War, countries where both the rulers and the people were content with the status quo were more likely to side with the West.44 Thus, monarchies across the region that benefited from their relationship with the British stayed with the West, while Turkey, having secured its independence decades earlier, saw Western support as a way to defend it against the Soviet threat. Where these regimes maintained the consent, or at least obedience, of the societies they governed—as in Jordan, the Gulf states, or Turkey—this orientation remained. Conversely, in countries like Iraq, Syria, and Egypt, widespread popular resentment of the status quo and the regimes that enforced it both increased the likelihood of political instability and the appeal of the Soviet Union as an ally.

At the same time, many countries that stayed within the Western camp experienced follow-on benefits that contributed to their stability, while those that tried to leave often suffered as a result. The United States offered economic and technical aid to its allies far in excess of what the Soviet Union could provide. These allies were also integrated into the global economy, often quite successfully, while those that defied the West, such as Iran or Iraq, ended up hobbled by sanctions.

Western military support played an important role, as well. The British sent troops to prop up the Jordanian monarchy in 1958, while in 1961—three decades before Operation Desert Storm—British military intervention helped protect Kuwait from Iraqi invasion. Conversely, there could be violently destabilizing consequences for those that sought to escape the Western orbit. Notably, the United States supported coups against governments in both Syria and Iran that Washington feared would take their countries in a pro-Soviet direction.

Finally, there was an ideological dimension to these Cold War divisions. Washington was always happy to ignore the undemocratic practices of its allies in the Middle East. Still, the Ba’athist regimes in Syria and Iraq, as well as the Qaddafi regime in Libya, displayed a degree of totalitarian ambition and systematic brutality that set them apart from other regimes in the region. Saddam Hussein demonstrated that, as a source of ideological inspiration, Stalinism is not conducive to stability. And in 2003, Washington demonstrated, yet again, that Western intervention wasn’t, either.

No Secret Solutions

For all the remappings of the Middle East over the past decade, however aspirational or ominous, the region’s borders have remained, on paper at least, unchanged. Despite incredible violence, the supposedly artificial states that emerged at the start of the twentieth century have, in a fragmented or hollowed out form, endured. The alternative maps that appeared, whether printed by the Atlantic or the Islamic State, remain exercises in imagination. This might well change. But so long as the new maps are appearing as magazine covers or pixilated social media posts and the official ones are being printed by national governments, the territorial status quo, such as it is, seems safe.

Unfortunately, looking at the process through which today’s map came to be doesn’t offer any secret solutions for securing peace and ending civil wars. The point is not to bemoan missed opportunities or slip into alternate history. Nor is it to imagine that somehow the heir to the Ottoman throne could play the role of Otto von Hapsburg in a modern Middle Eastern EU. Absent European colonialism, the Arab world was still unlikely to pass directly from Ottoman rule to liberal post-nationalism. Historical forces worked against implementing more flexible alternatives to the nation-state system then, and they still do today.

But seeing the way people have clashed over borders or struggled with their contradictions can still offer some insights. Turkey, for example, has reaped the benefits of its victory over imperialism for the past century. But the specter of Sevres has also fueled a fixation with building a strong centralized state in which expressions of cultural diversity have been forcibly suppressed. One result is a decades-long war with Kurdish separatists, which soon spilled over into Iraq and Syria. Solving this conflict will ultimately require a new political model, one that can render battles over borders and national identity irrelevant.

Looking back at the evolution of border regimes over the last century also shows that we can work to transcend them without completely eliminating them. We don’t need to change the lines on the map to mitigate their human toll, whether by making them easier to cross or by helping people secure rights within them.

This report is part of “Networks of Change: Reviving Governance and Citizenship in the Middle East,” a Century International project supported by the Carnegie Corporation of New York and the Open Society Foundations.

Header Image: Historical maps of the Levant. Source: Nicholas Danforth adapted from “Filastin risalesi,” Ottoman Military Publication, 1915 (author’s collection); Syria’s Independence Day, (Cairo: Taha Ibrahim and Yusuf Barladi Publishing House, 1920), author’s collection; and John Bartholomew and Son, Composite: Near East (London: The Times, 1922).

Notes

- “ISIS Celebrates Takeover of Nineveh Province, Says the ‘Sykes–Picot Borders’ Have Been Removed,” Middle East Media Research Institute, June 11, 2014, https://www.memri.org/jttm/isis-celebrates-takeover-nineveh-province-says-sykes-picot-borders-have-been-removed; “Video: Islamic State Media Branch Releases ‘The End of Sykes–Picot,’” Belfast Telegraph, July 1, 2014, https://www.belfasttelegraph.co.uk/video-news/video-islamic-state-media-branch-releases-the-end-of-sykes-picot/30397575.html.

- Undated segment of The Daily Show posted to YouTube by Rohin Sharma (@rohinksharma) on January 26, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?reload=9&v=dyxi0lqtGTQ; John R. Bolton, “To Defeat ISIS, Create a Sunni State” New York Times, November 24, 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/25/opinion/john-bolton-to-defeat-isis-create-a-sunni-state.html; Tim Arango, “With Iraq Mired in Turmoil, Some Call for Partitioning the Country,” New York Times, April 28, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/29/world/middleeast/with-iraq-mired-in-turmoil-some-call-for-partitioning-the-country.html.

- Robin Wright, “How 5 Countries Could Become 14,” New York Times, September 28, 2013, https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/interactive/2013/09/29/sunday-review/how-5-countries-could-become-14.html; Jeffrey Goldberg, “The New Map of the Middle East,” Atlantic, June 19, 2014, https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2014/06/the-new-map-of-the-middle-east/373080/; ames Gelvin, “Obsession with Sykes–Picot Says More About What We Think of Arabs than History,” The Conversation, May 12, 2016, https://theconversation.com/obsession-with-sykes-picot-says-more-about-what-we-think-of-arabs-than-history-58775.

- Steven Cook and Amr Leheta, “Don’t Blame Sykes–Picot for the Middle East’s Mess,” Foreign Policy, May 13, 2016, https://foreignpolicy.com/2016/05/13/sykes-picot-isnt-whats-wrong-with-the-modern-middle-east-100-years/.

- Samuel Dolbee, Locusts of Power: Borders, Empire, and Environment in the Modern Middle East (Cambridge University Press, 2023).

- Ussama Makdisi, “Cosmopolitan Ottomans,” Aeon, October 17, 2019, https://aeon.co/essays/ottoman-cosmopolitanism-and-the-myth-of-the-sectarian-middle-east; Joost Hiltermann, “The Middle East in Chaos: Of Orders and Borders,” International Crisis Group, May 25, 2018, https://www.crisisgroup.org/middle-east-north-africa/middle-east-chaos-orders-and-borders; Leon Hadar, “The Levant’s Lost Cosmopolitan Legacy,” American Conservative, August 26, 2025, https://www.theamericanconservative.com/the-levants-lost-cosmopolitan-legacy/.

- See, for example, the map accompanying William Miller’s The Ottoman Empire, 1801–1913 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1913).

- Ugur Umit Ungor, The Making of Modern Turkey: Nation and State in Eastern Anatolia, 1913–1950 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011); Ryan Gingeras, Sorrowful shores: violence, ethnicity and the end of the Ottoman Empire, 1912–1923 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009); İpek Yosmaoğlu, Blood Ties: Religion, Violence and the Politics of Nationhood in Ottoman Macedonia, 1878–1908 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2013); Anastasia N. Karakasidou, Fields of Wheat, Hills of Blood (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997).

- Eugene Rogan, The Fall of the Ottomans: The Great War in the Middle East, Basic Books, 2016; Ryan Gingeras, Fall of the Sultanate: The Great War and the End of the Ottoman Empire 1908-1922, Oxford University Press, 2016; M. Sükrü Hanioglu, A Brief History of the Late Ottoman Empire, Princeton University Press, 2010.

- On display at the İskenderun Naval Museum: https://farm8.staticflickr.com/7290/8731602620_b07be0c5c3_o.jpg.

- The Sykes–Picot Agreement, 1916, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/sykes.asp.

- Michael Provence, The Great Syrian Revolt And The Rise Of Arab Nationalism (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2005).

- Andrew Mango, Ataturk: The Biography of the Founder of Modern Turkey (New York: Abrams Press, 2002).

- Elizabeth Thompson, How the West Stole Democracy from the Arabs: The Syrian Congress of 1920 and the Destruction of its Historic Liberal-Islamic Alliance (New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2020).

- Michael Provence, The Last Ottoman Generation and the Making of the Modern Middle East (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2017).

- Sarah Shields, “Mosul, the Ottoman Legacy and the League of Nations,” International Journal of Contemporary Iraqi Studies 3, no. 2 (2009): 217–30.

- Sarah Pursley, Familiar Futures: Time, Selfhood, and Sovereignty in Iraq (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2019).

- Michael Provence, The Last Ottoman Generation and the Making of the Modern Middle East (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2017).

- Michael Provence, The Last Ottoman Generation and the Making of the Modern Middle East (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2017).

- Andrew Patrick, America’s Forgotten Middle East Initiative: The King–Crane Commission of 1919 (London: I. B. Tauris, 2015).

- “First Publication of the King–Crane Commission Report on the Near East,” Editor & Publisher, December 2, 1922.

- “Report of the American Section of the International Commission on Mandates in Turkey Paris,” Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States, Paris Peace Conference, 1919, Volume XII, Paris Peace Conf. 181.9102/9, August 28, 1919, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1919Parisv12/d380.

- “Report of the American Section of the International Commission on Mandates in Turkey Paris,” Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States, Paris Peace Conference, 1919, Volume XII, Paris Peace Conf. 181.9102/9, August 28, 1919, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1919Parisv12/d380.

- In addition to the works cited above, the online popularity of images such as the interwar Haifa–Beirut bus service testify, albeit somewhat anachronistically, to this nostalgia. See Joyce Karam (@Joyce_Karam), “A Haifa – Beirut bus service from 1920-1949. Things were not always as bitter and rough in Middle East,” Twitter (now X), September 27, 2018, https://x.com/Joyce_Karam/status/1045520294839021568.

- The Sykes–Picot Agreement, 1916, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/sykes.asp.

- “Question of the Frontier Between Turkey and Iraq,” report submitted to the League of Nations commission instituted by the council resolution of September 30, 1924.

- “Report of the Commission entrusted by the Council with the Study of the Frontier Between Syria and Iraq,” League of Nations, Geneva, September 10, 1932.

- Robert Fletcher, “Running the Corridor: Nomadic Societies and Imperial Rule in the Interwar Syrian Desert,” Past and Present 220, no. 1 (August 2013): 185–215.

- “Agreement Between Palestine and Syria and the Lebanon to Facilitate Good Neighborly Relations in Connection with Frontier Questions,” American Journal of International Law 21 , iss. S4: Supplement Official Documents (October 1927): 147–51.

- Cyrus Schayegh, “The Many Worlds of ‘Abud Yasin; Or, What Narcotics Trafficking in the Interwar Middle East Can Tell Us About Territorialization,” American Historical Review 116, iss. 2 (2011): 273–306.

- Asher Kaufman, Contested Frontiers in the Syria-Lebanon-Israel Region: Cartography, Sovereignty, and Conflict, (Washington, D. C.: Woodrow Wilson Center Press, 2013).

- “Agreement Between Palestine and Syria and the Lebanon to Facilitate Good Neighborly Relations in Connection with Frontier Questions,” American Journal of International Law 21 , iss. S4: Supplement Official Documents (October 1927): 147–51.

- “Agreement Between Palestine and Syria and the Lebanon to Facilitate Good Neighborly Relations in Connection with Frontier Questions,” American Journal of International Law 21 , iss. S4: Supplement Official Documents (October 1927): 147–51; Cyrus Schayegh, “The Many Worlds of ‘Abud Yasin; Or, What Narcotics Trafficking in the Interwar Middle East Can Tell Us About Territorialization,” American Historical Review 116, iss. 2 (2011): 273–306.

- Sarah Shields, “Mosul, the Ottoman Legacy and the League of Nations,” International Journal of Contemporary Iraqi Studies 3, no. 2 (2009): 217–30.

- Karl Sharro, “Our bold proposal to reshape Western Europe for a more stable and peaceful future. (Inspired by what Europe did elsewhere.),” Twitter (now X), April 28, 2017, https://x.com/KarlreMarks/status/857956492015788032.

- “How can you govern a country which has 246 varieties of cheese?” attributed to Charles de Gaulle, Ernest Mignon, Les Mots du Général Fayard, Paris, 1962.

- “Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States,” Paris Peace Conference, 1919, Volume XIII.

- Quoted in Charles Homer Haskins and Robert Howard Lord, Some Problems of the Peace Conference (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1920).

- Charles Homer Haskins and Robert Howard Lord, Some Problems of the Peace Conference (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1920).

- Charles Homer Haskins and Robert Howard Lord, Some Problems of the Peace Conference (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1920), p. 147, https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=iSYgAAAAMAAJ&pg=GBS.PA146&hl=en.

- Stefan Zweig, The World of Yesterday, (London: Pushkin Press, 2024).