The number of students enrolled in public charter schools has steadily grown since the inception of the charter model in the 1990s, and now accounts for 6 percent of the total number of students enrolled in public schools across the country.1 This statistic alone demonstrates the important role that charter schools play in the delivery of public education in the forty-four states and the District of Columbia that have adopted charter school laws.2 Over this period of growth, however, the charter school model has been the subject of heated controversy, including whether they equitably serve all students regardless of race, class, sex, disability, or first language.

Charter schools are publicly funded, voluntary enrollment schools created through a legislatively defined process that binds the school to the provisions of a performance contract in exchange for relief from compliance with a specified set of state statutes and regulations.3 While some charter schools have raised legal questions about the extent of their “publicness”4 and state laws often do not explicitly declare that charter schools are public, this report adopts the definition used in federal law that charter schools are a specialized form of public school,5 and therefore must ensure that they serve all segments of the public that funds them.6 In short, charter schools should only have a place in our public educational landscape if they further the public policy goal of advancing equal educational opportunity.7

Ensuring nondiscriminatory access to charter schools is both a mandate8 and challenge9 for those who authorize and operate them. Research has long documented that charter schools serve more homogeneous student populations.10 In particular, concern has been raised about charter schools enrolling smaller proportions of children with disabilities11 and the extent to which charter schools serve students requiring special instructional attention because their first language is not English.12 Still, researchers have also documented the existence of “intentionally diverse” charter schools that consider equity and access as defining characteristics for their educational approach.13

While the charter model continues to spark controversies,14 these debates should not distract policymakers from ensuring that charter schools serve all students equitably, and that policymaking should be guided by three assumptions:

- charter schools will be part of our public educational system for the foreseeable future;

- charter schools are neither inherently good, nor inherently bad; and

- charter schools should be employed to further goals of equal educational opportunity.15

This report employs those guiding assumptions to address the ways in which charter school policy can intentionally focus on equity. In other words, policymakers can only achieve educational equity for all children if they prioritize equitable access in all educational programming, including charter school policy. Accordingly, the report is divided into four sections. First, it reviews the charter school authorization cycle and the ways charter schools vary from state to state, all of which may impact charter schools’ ability to attract, retain, and equitably serve a diverse student body. Next, it examines the findings of research about charter schools in relation to various groups of students as well as research on funding and charter schools’ effects on traditional school districts. The third section discusses the challenges and opportunities that attend an intentional focus on equity in charter schools, and the fourth and final section argues for a comprehensive set of recommendations that address planning, oversight, and complaint procedures at all governmental levels to ensure that charter schools foster equitable practices for all children.

How Charter Schools Vary

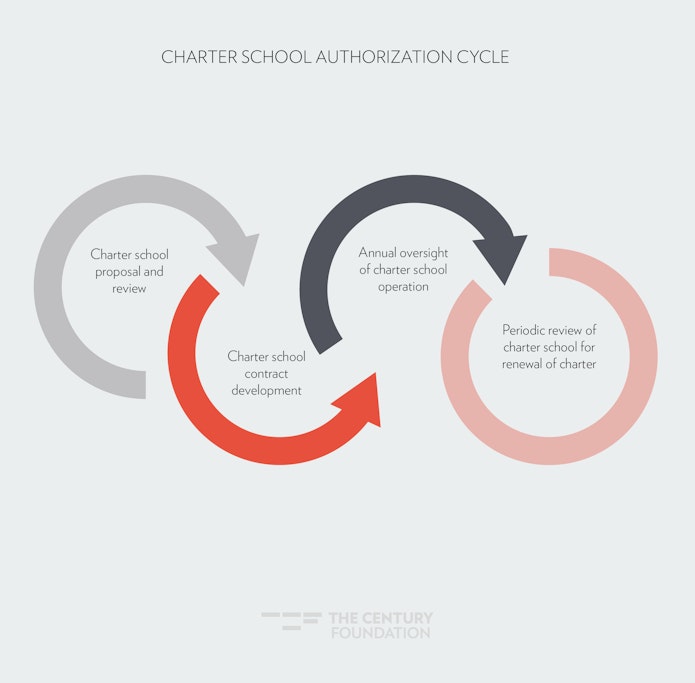

In order to understand the ways in which charters vary, and the import of that variance, it is first necessary to briefly review the stages in the cycle of a charter school, common to all states16 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

All states recognize and empower entities to act as charter school authorizers, which may be state or local agencies, independent boards, institutes of higher education, or some form of nongovernmental, nonprofit organization. It is these charter school authorizers that are responsible for reviewing proposals for charter schools and granting or denying their applications. For those schools with accepted applications, the next step in the process is the negotiation and development of the charter school contract (the charter itself). This performance contract defines the relationship between the authorizer and operator and establishes the standards to which the school will be held. Once agreement is reached on a charter contract, the school may begin operation, with the authorizer being responsible for oversight of the school and ensuring the school complies with the terms of the contract. Finally, at a time specified in the term of the charter contract, the authorizer must determine whether the school’s performance merits a renewal of the contract, or not. A school that is not renewed loses its authorization to operate as a public charter school.17

As this brief description illustrates, three entities have particular importance in the establishment of charter schools and therefore in ensuring that charter schools are intentional about equity. First, the state legislature defines precisely what the term “charter school” means in that state and enacts provisions that control the process in its entirety—from the elements that must be included in a proposal to the causes or reasons a charter school may have its charter revoked or non-renewed. Second, the charter school authorizer has the primary role of determining which schools will exist as charter schools and then holding those schools accountable to the performance contract. Finally, those who operate charter schools must comply with the standards set by the state and the authorizer.

Beyond these basics, charter schools vary considerably from state to state; charter schools are, in fact, creatures of the legislature that fashioned them. States vary with regard to how many charter schools may exist, what rules and regulations schools must adhere to and those from which they are exempted from compliance, whether private schools may convert to public charter schools, whether schools may deliver instruction online, whether teachers must be certified, and whether schools may adopt admissions criteria.18 For the purposes of this analysis, one of the most consequential variances may be found in the entities granted the authority to charter—both in number and type.19 While some states confine that authority to specially appointed boards or agencies established for that purpose or to local school districts, other states grant authority more expansively and permit universities and nonprofit organizations to grant charters. In addition to how many and which entities may serve as charter school authorizers, states also vary with respect to the scope of each authorizer’s authority. For example, some states limit authorizers to a specified geographic region or a certain number of schools. In contrast, an authorizer with unlimited geographic scope may approve a school anywhere—even if local school authorities or voters object to the school.20 The ability of an authorizer to understand local needs or adequately oversee the operation of a school geographically distant could impact the quality of that oversight. Likewise, authorizers with large portfolios of charter schools to manage may be challenged to obtain the capacity necessary to attend to each school’s operation.21 In addition, multiple authorizers permit charter school applicants to “shop” for an authorizer. On the other hand, proponents of charter schools may argue that statewide authorizers with large portfolios could bring more consistency to the application process and may also have more time, expertise, and resources to devote to becoming high-quality authorizers.

While state legislatures may relieve charter schools from compliance with state rules that bind other public schools, they have no authority to exempt charter schools from compliance with federal laws.

As noted earlier, charter schools also vary with regard to which portions of state law the school must follow and which do not apply. One important factor to keep in mind, however, is that while state legislatures may relieve charter schools from compliance with state rules that bind other public schools, they have no authority to exempt charter schools from compliance with federal laws. Charter schools are fully bound by the nondiscrimination provisions of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act (race, color, or national origin), Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 (sex), Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 (disability), the Americans with Disabilities Act (disability), and the Equal Educational Opportunities Act (race, color, sex, or national origin).22 In addition to these federal laws that prohibit discrimination, charter schools must also comply with the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) and the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), both of which bind states to complex rules and regulations as a condition of federal financial support to ensure that all students have available a free appropriate public education.23 IDEA and ESSA also both include requirements that public schools, including charter schools, collect and report data to state authorities regarding student performance and the use of suspension and expulsion.

Trends across Charter Schools

What, then, does research suggest about charter schools’ record of serving all types of students? And how does the operation of charter schools affect the resources available to students in traditional public schools? This section reviews the research on charter school enrollment with respect to different student characteristics—race, language and national origin, socioeconomic status, and disability—as well as studies on the effects of charter school funding on the resources available to all public schools and students.

Race

In the aggregate, it would appear that charter schools have more equal proportions of white, black, and Hispanic students than traditional public schools. The racial composition of charter schools was 33 percent white, 27 percent black, and 32 percent Hispanic (school year 2015–16)24 while the racial composition of traditional public schools was 59 percent white, 17 percent black, and 19 percent Hispanic.25

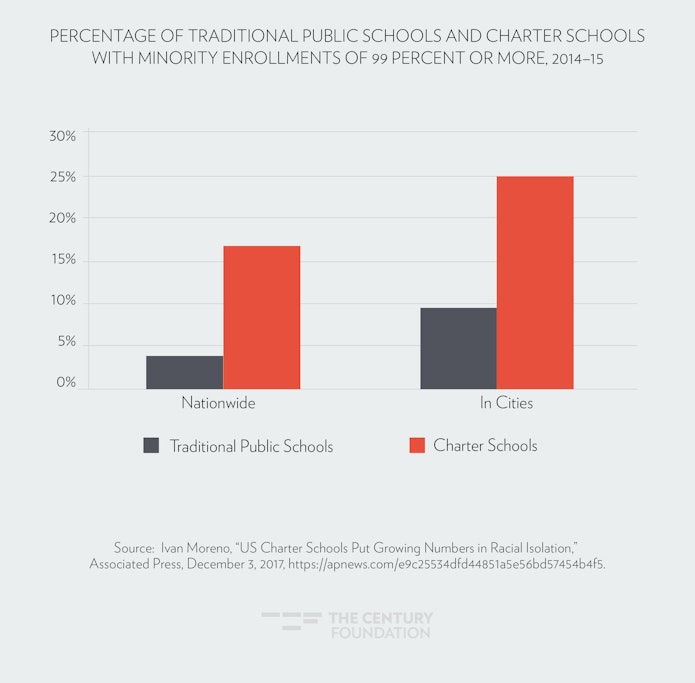

However, at the school level, charter schools tend to have higher concentrations of black and Hispanic students than white students. For instance, in the 2015–16 school year, a lower percentage of charter schools had more than 50 percent white enrollment than traditional public schools (34 percent to 58 percent). By contrast, a higher percentage of charter schools had 50 percent black enrollment than traditional public schools (23 percent to 9 percent), and a higher percentage of charter schools had 50 percent or more Hispanic enrollment than traditional public schools (25 percent to 16 percent). Furthermore, an analysis of national enrollment data conducted by the Associated Press found that in the 2014–15 school year, more than 1,000 out of 6,747 charter schools were 99 percent minority.26 As Figure 2 shows, while 4 percent of traditional public schools had minority enrollments of at least 99 percent, 17 percent of charter schools reached this percentage. In cities, where most charter schools are found, 25 percent of charter schools were 99 percent minority, as compared to only 10 percent of traditional public schools.27 Some of this variation may stem from the specific neighborhood locations of charter schools, but if so, that raises additional policy questions about where charter schools choose and are approved to open.

Figure 2

An examination of charter school enrollment conducted by the Brookings Institute revealed that charter schools tend to have higher racial imbalances than traditional public schools, particularly with respect to black students. In fact, “[t]he proportion of outliers among charter schools, in terms of white, black and Hispanic representation [were] about 11, 19, and 2 percentage points higher, respectively, than for traditional public schools.”28 Although the paucity of charters in most districts means they are unlikely to affect the racial composition of other schools in the host district,29 large urban districts with a high concentration of charter schools may feel the effects of charter school enrollment practices. Some state policymakers have enacted provisions to address the racial composition of charter schools, but current jurisprudence on the use of individual racial characteristics in admissions decisions suggests that in practice the provisions act more as aspirational targets, rather than consequential goals that the charter school reflects the racial demographics of the broader community.30 It is important to recognize, however, that a variety of race-conscious and race-neutral strategies are still available for states, charter school authorizers, and charter school operators that value racial integration and desire to realize the intent of these provisions.31

Language and National Origin

The concerns raised about the populations served by charter schools also apply to issues of national origin when it is associated with children whose first language is other than English and therefore require schools to take “affirmative steps” to ensure language learning needs are met.32 In the 2013–14 school year, there were 4.7 million students classified as English Language Learners (ELLs). This number constituted 9.3 percent of the public-school population.33 By contrast, there are no national data disaggregating enrollment of ELL students in charter schools. Charter school advocates proclaim that charter schools are serving English Language Learner (ELL) students while critics maintain that ELL students are underrepresented in charter schools. Congress asked the Government Accountability Office (GAO) to resolve this debate, but the agency could not complete its assignment because of unreliability or insufficiency of the data provided to the U.S. Department of Education.34 Researchers have begun to address this question at the state and local levels, with varying results.35

Socioeconomic Status

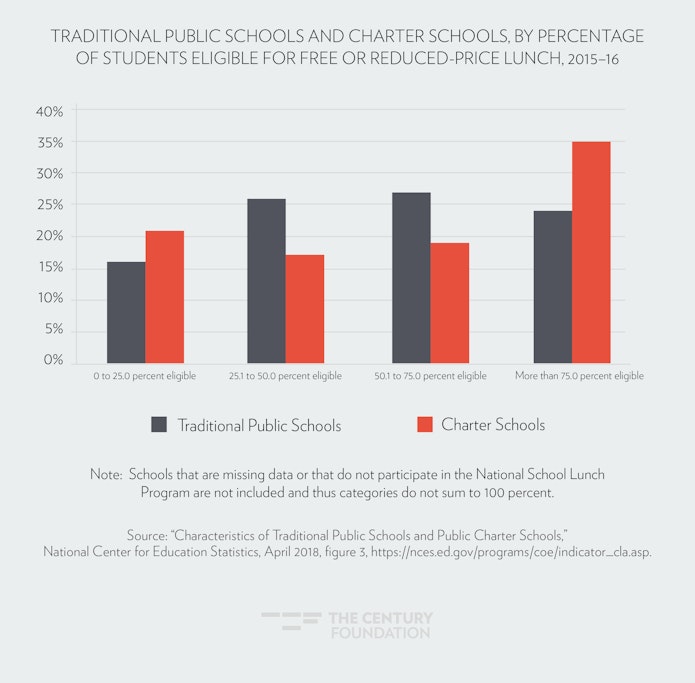

Concentration of students in charter schools according to socioeconomic status has also raised concern. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, charter schools are more likely than traditional public schools to be high-poverty schools (more than 75 percent eligible for free or reduced priced lunch, or FRPL) or low-poverty schools (up to 25 percent eligible for FRPL). In the 2015–16 school year, 35 percent of charter schools and 24 percent of traditional public schools were high-poverty schools; 21 percent of charter schools and 16 percent of traditional public schools were low-poverty schools.36 Conversely, there were higher percentages of traditional public schools in the middle-poverty categories (25 percent–50 percent FRPL and 50 percent–75 percent FRPL) than charter schools.37 In traditional public schools, the percentages were 26 percent and 27 percent, respectively. In charter schools, the corresponding percentages were 17 percent and 19 percent.38(See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

Disability

Researchers have also directed attention to the number of children with disabilities served by charter schools. A 2012 study by the federal Government Accountability Office found that charter schools served markedly fewer children with disabilities and fewer children with low prevalence disabilities and complex learning needs.39 The agency recommended “that the Secretary of Education take measures to help charter schools recognize practices that may affect enrollment of students with disabilities by updating existing guidance and conducting additional fact finding and research to identify factors affecting enrollment levels of [children with disabilities] in charter schools.”40 In a subsequent study using 2013–14 data, charter schools enrolled a lower percentage of students with disabilities under IDEA than did traditional public schools (10.6 percent for charter schools, versus 12.5 percent for traditional public schools).41 Charter schools and traditional public schools enrolled almost the same percentage of students who qualified for Section 504 services (1.9 percent versus 1.8 percent).42 Because of the way eligibility is determined under each law, the distinction between the two groups serves as a crude indicator of the severity of children’s disabilities served in each type of school. Children with mental or physical impairments that substantially limit a major life activity are eligible for protection from discrimination under Section 504.43 Accordingly, traditional public and charter schools need to provide reasonable modifications to address the needs arising from their disability, which may or may not include special education. In order to be eligible under IDEA, the child’s disability must adversely affect educational performance such that special education is needed to appropriately serve the needs associated with the disability.44 In other words, by definition, children eligible under IDEA usually have more extensive instructional needs than do those eligible only under Section 504.

The percentage of students with disabilities in charter schools also differed with respect to legal status under the IDEA. About 54 percent of charter schools were their own local education agency (LEA—the entity identified under IDEA as responsible to ensure a free appropriate public education), while 46 percent of charter schools were part of an LEA (typically a traditional school district). Charter schools that operated as their own LEA had a higher percentage of students with disabilities (11.5 percent) than charter schools that were part of an LEA (9.7 percent). These numbers were still below the enrollment percentage of students with disabilities in traditional public schools (12.5 percent).45

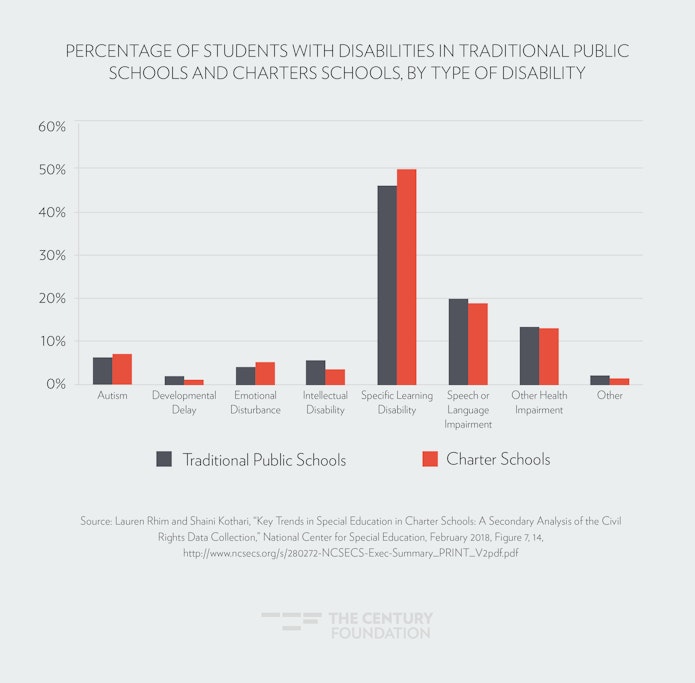

The percentages of students with disabilities also differed in terms of disability categories. (See figure 4.) For instance, charter schools served a higher percentage of students with specific learning disabilities (49.5 percent for charter schools, versus 46 percent for traditional public schools), autism (7.2 percent versus 6.5 percent) and emotional disturbance (5.1 percent versus 4.1 percent) than traditional public schools.46 Conversely, charter schools enrolled lower percentages of students with developmental delays (0.9 percent versus 2.1 percent) and intellectual disabilities (3.6 percent versus 5.9 percent).47 Charter schools that were part of an LEA enrolled a significantly larger percentage of students with speech or language impairments (21.4 percent) than charter schools that were their own LEA (17.9 percent). By contrast, charter schools that operated as their own LEA had a significantly higher percentage of students with emotional disturbance (6.1 percent versus 3.1 percent).48

Figure 4

Funding

Two issues around funding are also important in any consideration of charter schools and equity: (1) the effects of charter schools on traditional public school districts, and (2) the fiscal practices of charter schools. Supporters of charter school expansion have claimed that it poses little to no harm on the school districts in which they are located. Bruce Baker summarizes the argument in the following manner:

The logic goes, if charter schools serve typical students drawn from the host district’s population, and receive the same or less in public subsidy per pupil to educate these children, then the per pupil amount of resources left behind for children in district schools either remains the same or increases. Thus, charter expansion causes no harm (and in fact yields benefits) to children remaining in district schools.49

According to Baker, this reasoning is faulty because it fails to account for “the structure of operating costs and dynamics of expenditure reduction.”50

Gordon Lafer expands on the impact that charter schools can pose on traditional school districts. Because charter schools attract students from multiple schools in a district, the number of students who transfer out of an individual school may be insufficient to trigger significant cost reductions. In addition, other costs, including building maintenance, running cafeterias, and maintaining digital technologies, are not changed by modest enrollment declines.51

Even if policymakers adopt the position that all families should be able to choose their child’s school and school choice is valued for its own sake, policymakers must take care that the manner in which charter schools are created and funded does not subvert state constitutional guarantees to public education.

While all public school systems must adjust to the normal fluctuations of student enrollment from families moving into and out of the school district, unchecked charter school policy may introduce a new level of unpredictability into the calculations made to account for enrollment swings and the budgetary responses to those changes. In addition, even if policymakers adopt the position that all families should be able to choose their child’s school and school choice is valued for its own sake, policymakers must take care that the manner in which charter schools are created and funded does not subvert state constitutional guarantees to public education. Derek Black cautions that states may run afoul of such state constitutional limits if the systems created “systematically advantage choice programs over public education” or have the “practical effect” of “imped[ing] educational opportunities in public schools.”52 As he explains, “Education clauses in state constitutions obligate the state to provide adequate and equitable public schools. Any state policy that deprives students of access to those opportunities is therefore unconstitutional.”53

The expansion of charter schools should be of particular concern to minority school districts, many of which are already underfunded. A study conducted by David Arsen and colleagues on the reasons that school districts got into financial trouble in Michigan lends credence to this concern.54 This study found that districts with high concentrations of black students had “large and striking” declines in fund balances.55 Arsen and colleagues further found that these high-concentration districts were “much more likely to be subject to intense charter school penetration, to lose students to inner-district school choice, and to have higher concentrations of students with disabilities.”56 With respect to charter penetration, the negative effects on school district finances increased as the percentage of charter school students rose from 5 percent to 25 percent of resident students.57

A recent news report from California illustrates the potential effect funding a charter school may have on a school district.58 The Olive Grove Charter School applied to the Santa Ynez High School District for authorization, but was denied. The charter school appealed to the California Department of Education, which overrode the denial and ordered the school district to sponsor the charter school. As a result, the school district must now provide financial support to the charter school. The superintendent explained the impact on the already financially strapped district. “This decision by the Department of Education could be crippling, and the ripple effects will be massive. We are already facing a $750,000 structural deficit this year, so adding an additional $700,000 with potentially more in the coming years will ruin us.”59 Requiring that authorizers consider the financial impact of a charter school on the school district in which it is to be located would help to avoid similar situations.

Another issue related to charter school funding is the matter of the fiscal health of charter schools. Research suggests that financial difficulties is one of the most common reasons for charter school closure.60 In fact, a recent study of Arizona charter schools concluded that 10 percent of the schools studied were in “significant financial distress” such that closure was imminent, with an additional 10 percent at risk for closure.61 Given that charter schools are concentrated in urban areas and as such these schools tend to serve our most vulnerable students, the disruption caused by school closures exacerbates rather than ameliorates concerns for equitable access to high quality education for our urban centers.62 Mandating that charter schools employ appropriate approaches to financial management ensures that the public funds invested are spent for the educational purposes for which they were intended.63

Challenges and Opportunities for Advancing Equity

As the foregoing review illustrates, charter schools that serve diverse student populations and achieve equitable educational opportunities for all enrolled do not happen by chance. Simply put, equity requires intention. To be fair, that maxim is also true in traditional public school settings. In fact, if the history of public education has taught us anything, it is that achieving equal educational opportunity is difficult and made even more so when problems are allowed to form and fester. The charter school process provides the opportunity to attend to issues of equitable access and performance from the inception of the school. As such, equitable access must be a design principle throughout the charter school authorization cycle.64 Equity should be baked into the charter school proposal process, the charter school contract, the annual oversight of charter school performance, and the periodic consideration of charter renewal (see Figure 1).

Moreover, delivery of equitable educational programs in charter schools requires policymakers’ explicit attention at multiple levels. That is, structuring intentional equity needs parallel commitments from federal officials, state officials, and charter school authorizers. If all policy is a codification of values,65 then the value of equal educational opportunity should be apparent in charter school policy at all three levels. Congress and the U.S. Department of Education have roles to define federal policy, clarify that charter schools are no less accountable for equitable access, and provide oversight to states to ensure that both planning and oversight include measures specific to charter school operation. State legislatures play a primary role by ensuring that the statutes that enable charter schools explicitly address equity throughout. Finally, authorizers must be on the forefront to guarantee that charter schools respect “[t]he rights of all students to enjoy equitable access to the schools of their choice, to receive appropriate services, and to be treated fairly” while also protecting “[t]he public interest in ensuring that publicly funded programs are accountable, transparent, well governed, efficient, and effectively administered.”66

Numerous charter schools across the country have been able to accomplish this goal.67 In fact, the National Education Policy Center recently recognized Broome Street Academy Charter High School (New York City) and Health Sciences High and Middle College Charter School (San Diego, California) as two of six Gold Recognition recipients for their Schools of Opportunity Project.68 This project “recognizes high schools that have demonstrated an extraordinary commitment to equity and excellence by giving all students the opportunity to succeed.”69 Broome Street increased academic supports for all students and changed discipline policies to focus on restorative justice and avoid exclusionary practices. Health Science Charter School accomplishes its goals by a dedication to inclusive practices and heterogeneous classes. While these schools are exemplars, they are not alone. A study of thirteen charter schools in two cities found that “intentionally diverse” charter schools employed three conscious recruitment strategies: (1) targeted recruitment of minority communities, (2) local decisions to maximize diversity, and (3) using existing networks and word-of-mouth to recruit a broad pool of applicants.70 School staff uniformly championed equitable practices and purposefully sought to leverage the advantages of a diverse population for all learners.

Recommendations to Address Equity and Opportunity

To achieve the goal of intentional equity, we recommend a comprehensive suite of actions aimed at leveraging actions at the federal, state, and authorizer levels. These recommendations are organized into three approaches: (1) planning; (2) oversight; and (3) complaint procedures. Addressing each of these facets of charter school operation ensures that all involved are mindful about equity throughout the charter school authorization cycle and take specific explicit action to address the difficulties documented by research and associated with leaving issues of equity and access to happenstance. (We briefly review each approach here, followed by recommendations for each approach. An appendix is provided that collects recommendations for all three approaches.).71

Planning

Each charter school authorization should be recognized as a significant investment of public dollars—one that may even be shielded from voter input if the authorizer is not a publicly elected board. As such, it is essential that any investment be supported by adequate planning to ensure a wise use of public monies. Planning provisions should employ both incentives and mandates as means to accomplish the goal of equal educational opportunity. For example, the federal government provides financial support for charter schools through its Charter Schools Program.72 We suggest that the federal government adopt funding priorities for that program that set priorities for grant awards for those applicants that clearly describe their strategies to serve a diverse set of learners. To complement that incentive, we recommend that the U.S. Department of Education require states to include descriptions of their charter school programs and the measures in place to ensure equity as part of the state plans required under both IDEA and ESSA. As a part of those plans, states should clarify that all federal and state nondiscrimination standards apply to all charter school authorizers. Some federal mandates only apply to those entities that receive federal financial assistance, referred to as “recipients” in those laws (for example, Title VI, Title IX, Section 504). If states permit entities that do not receive federal funds to authorize charter schools, they should require those authorizers to comply with the standards set forth in those federal laws regardless of whether the authorizer would typically be considered a “recipient” of federal funds.

In addition to federal mandates and incentives, we suggest that states establish parallel incentives and mandates to ensure that charter school aspirants plan for equity. For example, states could incentivize equity by giving priority to applications that respond to a request for proposals that address identified goals related to concerns revealed in an analysis of state data (for example, innovative programs to address concerns for language learning programs). At the same time, states could also create new requirements for charter schools by adopting a set of rebuttable legal presumptions as a matter of state law. A rebuttable legal presumption can be analogized to a default setting on a computer. Like a default setting that operates as matter of course unless changed, a rebuttable legal presumption declares an action invalid (or valid) unless sufficient evidence is provided to rebut that presupposition—to suggest the maxim should not apply in a particular instance. As we explained in 2012:

[W]e recommend state legislators adopt a series of rebuttable legal presumptions that trigger greater scrutiny and greater accountability to ensure that each charter school advances educational opportunity. Suggested language for these presumptions appears in the accompanying separate model code, but the intent is the same for all; to declare that some types of schools are presumptively adverse to public policy and therefore may not bear the imprimatur of the state as a public charter school without substantial justification to ensure non-discriminatory intent, effect, or both. In each instance, the presumption could be overcome if evidence could be marshaled to document how the school is actually consistent with and not counter to equal educational opportunity. Moreover, that evidence could include documentation of parental satisfaction, although this alone would be insufficient to show an advancement of the equity goals of charter policies. This requirement is consistent with the non-discriminatory language in federal law (Title VI, Title IX, the EEOA, Section 504, the ADA, the IDEA and the [ESSA]). Likewise, requiring justification replicates the standard to which courts would hold any program alleged to be discriminatory. Requiring such justifications whenever a charter contract is initiated and renewed ensures that charter schools operate in a manner consistent the principles of equal protection.73

To address some of the fiscal issues associated with charter schools, we suggest two approaches: (1) the articulation of a clear financial plan, and (2) a statutory requirement that authorizers consider the fiscal impact of the charter school on the school district in which the school will be located.

Of course, the planning requirements written into federal and state law would have to be enforced by charter school authorizers. Therefore, authorizers should be required to hold charter school aspirants to a clear set of standards for both proposals and charter contracts. Those provisions should not only declare that equitable access is a goal, but also detail how that goal will be accomplished, including student recruitment, acquisition of appropriate staff, development of curriculum and special services, adoption of policies, and communication with parents. Authorizers should also be required to enforce the rebuttable presumptions adopted in state law. Authorizers’ approach to all of the above should be clearly articulated in a plan provided to the state for approval.

Recommendations for achieving intentional equity through planning provisions include:

Federal Level

- Congress should set priority for federal charter school funding that requires attention to equity.

- Congress should require states, as part of ESSA and IDEA state plan approvals, to detail how charter schools will further equity and avoid exacerbating inequities.

State Level

- States should set approval and funding priorities for charter schools that address equitable outcomes.

- States should amend charter school laws/regulations to state explicitly that all charter schools are public schools and are bound by all state and federal nondiscrimination requirements.

- States should explicitly state that all charter school authorizers are bound by all state and federal nondiscrimination requirements as a condition of exercising their chartering authority, regardless of “recipient” status.

- States should require authorizers, as a matter of their oversight throughout the charter school lifecycle, to provide a plan to demonstrate how they will ensure that the charter schools in their purview promote equitable outcomes.

- States should set charter proposal standards that require charter school aspirants to plan explicitly for special student populations, including children with disabilities and children whose first language is not English.

- States should adopt charter school proposal standards that require charter school aspirants to explain how the proposed school would address local patterns of student performance and discipline.

- States should require, as an element of proposal review, that charter school authorizers consider the fiscal impact of a charter school on the school district in which is the school proposes to be located.

- States should explicitly allow or not prohibit charter schools to consider diversity-related factors (such as socioeconomic status or educational risk factors) in their lottery to encourage integration.

- States should establish rebuttable presumptions related to nondiscriminatory operation, including admissions standards, curricular expectations, data collection, and data reporting.

- States should prohibit charter schools from requiring mandatory parent volunteer hours.

- States should include requirements and funding for transportation of charter school students that are similar to those that apply to district students.

- States should require charter schools to participate in the federal free and reduced price lunch program (or to provide a comparable free meals program).

Authorizer Level

- Authorizers should establish protocols for proposal review that prioritize equal educational opportunity.

- Authorizers should consider the development and articulation of requests for proposals to address directly local problems of practice related to equitable student opportunities and performance.

- Authorizers should require clear articulation of how a school’s selected curricular approach will foster equal educational opportunity, including the peer-reviewed research that supports the curricular choices proposed.

- Authorizers should require that proposals detail the precise ways the charter school will recruit a diverse student body.

- Authorizers should require that proposals include a clear articulation of discipline standards.

- Authorizers should require clear articulation of how language learning needs of children whose first language is not English will be met, including program development, program evaluation, acquiring appropriate staff expertise, and provision of staff development.

- Authorizers should require clear articulation of how the learning needs of children with disabilities will be met, including program development, program evaluation, acquiring appropriate staff expertise, and provision of staff development.

- Authorizers should set clear data sharing requirements as part of the charter school contract that includes academic performance, attendance, in-school and out-of-school suspension, expulsion, and student attrition.

- Authorizers should require as part of the charter school contract that a checklist of standards must be met prior to recruitment of students, including health and safety, appropriate staffing (including access to special education services), publication of a student/parent handbook, and admission procedures.

- Authorizers should ask charter applicants for detailed planning regarding how they will disseminate information to prospective students and parents, including efforts to reach families with diverse racial, ethnic, linguistic, and socioeconomic backgrounds and students with disabilities.

- Authorizers should require as part of the charter school contract that all school fees are reasonable and comply with state standards and none serve as a barrier to serving a diverse student body.

- Authorizers should require as part of the charter school contract that any subcontracts with for-profit education management organizations (EMOs) and nonprofit charter management organizations (CMOs) be reviewed and approved to ensure funds are spent in reasonable ways (for example, staffing, facilities rent, and so on).

Oversight

The second series of recommendations all revolve around adequate oversight of charter school operation to ensure that plans are implemented and goals achieved. To that end, we recommend that the federal government require the collection of attrition data. In other words, a comprehensive approach to the oversight of schools that by definition only enroll students on a voluntary basis must consider why parents and families leave. An example best illustrates this issue. Suppose, for example, that a family becomes unhappy with a school because of exclusionary disciplinary standards that fall more heavily on students of color. Parents in this predicament have two broad choices—stay and try to change the practices, or leave for a school that employs different approaches. Without attrition data, authorizers, state officials, and federal officials may never understand the role alleged discriminatory practices had on parents’ choices. In fact, to truly attend to this issue, attrition data should be collected for all available publicly funded choices (public school, charter school, neighboring public school through open enrollment, or private school that participates in a voucher program, education savings account, or tax credit scholarship). Regular collection and review of attrition data will help to uncover potential problems and ensure equitable practices.

We also recommend a sequence of actions that authorizers should take as part of their oversight responsibilities, both on an annual basis and whenever considering renewal of an expiring charter. These provisions mandate that authorizers consider student demographics and service provision as part of any charter school performance review. Finally, we believe that comprehensive oversight demands that state officials have the authority to review the activities of charter school authorities and take action, if necessary. In the same way that charter schools can have their charters revoked for inadequate performance, states should be able to revoke the authority to charter from any authorizer that fails to fulfil its obligation to provide adequate oversight to the charter schools under its supervision.

Recommendations for achieving intentional equity through charter school oversight provisions include:

Federal Level

- The U.S. Department of Education should require states to provide charter school attrition data in addition to data on performance and discipline, and should monitor the same as a part of its regular oversight of state use of federal funds.

- The U.S. Department of Education should clarify that “cell size” (the number of students in a group) cannot be used to avoid collecting or reporting data to the state, or from the state to the federal government, and that states must regularly consider how they will ensure that schools that serve small populations of student subgroups are appropriately serving those populations.

State Level

- States should review authorizers for performance on oversight responsibilities related to equitable provision of educational opportunities (clear statements regarding proposal requirements, clear statements regarding charter contract development, regular oversight protocols, and clear expression of equitable standards in renewal and revocation standards).

- States should revoke authorizer authority for any entity that does not adequately collect and review data or appropriately monitor the charter schools in their portfolio for equitable student treatment.

- States should periodically conduct research to determine parental reasons for charter school selection and withdrawal.

Authorizer Level

- Authorizers should collect and review annual data on academic performance, student discipline, student attrition, staff expertise, and staff attrition.

- Authorizers should ensure that schools “backfill” to enroll new students when students leave.

- Authorizers should review annual budgets to ensure that charter school expenditures are reasonable and direct the majority of resources directly to teaching and learning.

- Authorizers should periodically review charter school websites, policies, and student/parent handbooks to ensure appropriate attention to equitable practices and outcomes.

- Authorizers should consider student demographics in relation to the area from which students are recruited as part of renewal and revocation considerations.

- Authorizers should require, as an element of annual oversight, any charter school with a homogeneous student population to provide an explanation for the result and develop a plan to attract a more diverse student body.

- Authorizers should enforce rebuttable presumptions for charter school nonrenewal for any charter school serving a student body with significantly different racial demographics and that is unable to provide adequate justification for continuance in relation to equal educational opportunity.

- Authorizers should enforce rebuttable presumptions for charter school nonrenewal for any charter school that is serving significantly fewer children with disabilities and children learning English and that is unable to provide adequate justification for continuance in relation to equal educational opportunity.

Complaint Procedures

Finally, we endorse steps designed to bolster and clarify complaint procedures. In a case from 1947, the U.S. Supreme Court declared that “a right without a remedy is no right at all.”74 That phrase recognizes that rights must be enforced for them to be more than hollow promises. To that end, we suggest attention to complaint procedures to ensure comprehensive and effective enforcement of standards of equitable access. These provisions require both the creation and publication of clear processes for complaint if a charter school or a charter school authorizer neglects its duty of nondiscrimination. However, it should also be noted that the system we advocate relies more heavily on planning and oversight. In our view, done correctly, complaint procedures should serve as a failsafe that is necessary only in the event that planning and oversight are unsuccessful in engineering the equitable access we believe must be the hallmark of all public education options.

Recommendations for achieving intentional equity through charter school complaint provisions include:

Federal Level

- The U.S. Department of Education should develop and provide clear guidelines to parents of children enrolled in charter schools regarding their rights and the options available to them for dispute resolution.

- The U.S. Department of Education should require states to collect and report data to the federal agency regarding complaints received about charter schools alleging discriminatory treatment, policies, or practices.

- The U.S. Department of Education should establish a rule that any charter school operator, charter school chain, or charter school management organization found by state or federal educational authorities or a charter school authorizer to have violated state or federal discrimination standards or that engaged in behaviors that resulted in the revocation or nonrenewal of a charter for a cause related to equal education opportunity is ineligible for federal charter school grants for a minimum of five years

State Level

- States should establish a complaint procedure to allow for investigation of any allegation that a charter school authorizer does not adequately oversee charter school operation.

- States should require parents to complete a charter school withdrawal form that provides a reason for withdrawing to ensure appropriate oversight of equitable practices.

- States should require authorizers to investigate allegations of discriminatory treatment or practices as a motivation for parents withdrawing a child from a charter school.

- States should establish a rule that any charter school operator, charter school chain, or charter school management organization found by state or federal educational authorities or a charter school authorizer to have violated state or federal discrimination standards or that engaged in behaviors that resulted in the revocation or nonrenewal of a charter for a cause related to equal education opportunity is ineligible for a charter from any state authorizer for a minimum of five years.

Authorizer Level

- Authorizers must establish complaint resolution procedures related to any state and federal nondiscrimination standards.

- Authorizers should ensure that each charter school has adopted and published policies regarding how and with what agency parents may file complaints.

Conclusion

Charter schools can and should play a role in realizing our longstanding national commitment to equal educational opportunity. Doing so will require dedication and attention from policymakers at all levels and throughout each stage of the charter school authorization cycle and with a particular focus on planning, oversight, and complaint procedures as a comprehensive strategy to achieve intentional equity.

Download the Appendix

Notes

- “Public Charter School Enrollment,” National Center for Education Statistics, March 2018, https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_cgb.asp.

- “School choice. School choice in America dashboard,” EdChoice.org, accessed September 22, 2018, https://www.edchoice.org/school-choice/school-choice-in-america.

- Preston C. Green III and Julie F. Mead, Charter Schools and the Law: Establishing New Legal Relationships (Norwood, MA: Christophe-Gordon Publishers, 2004), 1.

- Preston Green, Bruce Baker, and Joseph Oluwole, “Having it both ways: How charter schools try to obtain funding of public schools and the autonomy of private schools,” Emory Law Journal 63, no. 2, (2013): 303–39.

- 20 U.S.C. §7221i (2015).

- Catherine E. Lhamon, “Dear Colleague Letter on Charter Schools’ Legal Obligations under Federal Civil Rights Law,” United States Department of Education, Office for Civil Rights, May 14, 2014, https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/letters/colleague-201405-charter.pdf.

- Julie F. Mead and Preston C. Green, “Chartering Equity: Using Charter School Legislation and Policy to Advance Equal Educational Opportunity,” National Education Policy Center, 2012, http://nepc.colorado.edu/publication/chartering-equity.

- Catherine E. Lhamon, “Dear Colleague Letter on Charter Schools’ Legal Obligations under Federal Civil Rights Law,” United States Department of Education, Office for Civil Rights, May 14, 2014, https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/letters/colleague-201405-charter.pdf.

- Julie F. Mead and Suzanne E. Eckes, “How School Privatization Opens the Door for Discrimination,” National Education Policy Center, 2018, http://nepc.colorado.edu/publication/privatization.

- Huriya Jabbar, and Terri S. Wilson, “What is diverse enough? How ‘intentionally diverse’ charter schools recruit and retain students,” Education Policy Analysis Archives 26, no. 165 (2018), http://dx.doi.org/10.14507/epaa.26.3883.

- “Charter Schools: Additional Federal Attention Needed to Protect Access for Children with Disabilities,” Government Accountability Office, June 2012, https://www.gao.gov/assets/600/591435.pdf.

- “Education Needs to Further Examine Data Collection on English Language Learners in Charter Schools,” Government Accountability Office, August 2013, https://www.gao.gov/assets/660/655930.pdf.

- Ibid.; Richard Kahlenberg and Halley Potter, “Diverse charter schools: Can racial and socioeconomic integration promote better outcomes for students?” The Century Foundation, 2012, https://www.issuelab.org/resources/12746/12746.pdf; Halley Potter and Kimberly Quick, “Diverse-by-design charter schools,” The Century Foundation, May 15, 2018, https://tcf.org/content/report/diverse-design-charter-schools/.

- Chester E. Finn, Bruno V. Manno, and Gregg Vanourek, Charter Schools in Action: Renewing Public Education (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000); Joe Nathan, Charter Schools: Creating Hope and Opportunity for American Education (San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass, 1996); Roslyn Arlin Mickelson, Martha Bottia, and Stephanie Southworth, “School Choice and Segregation by Race, Class, and Achievement,” Education Policy Research Unit, March 2008, https://nepc.colorado.edu/sites/default/files/CHOICE-08-Mickelson-FINAL-EG043008.pdf; Erica Frankenberg, Genevieve Siegel-Hawley, and Jia Wang, “Choice without Equity: Charter School Segregation and the Need for Civil Rights Standards,” The Civil Rights Project/Proyecto Derechos Civiles at UCLA, https://www.civilrightsproject.ucla.edu/research/k-12-education/integration-and-diversity/choice-without-equity-2009-report/frankenberg-choices-without-equity-2010.pdf; Diane Ravitch, Reign of Error: The Hoax of the Privatization Movement and the Danger to America’s Public Schools (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2013).

- Julie F. Mead and Preston C. Green, “Chartering Equity: Using Charter School Legislation and Policy to Advance Equal Educational Opportunity” National Education Policy Center, 2012, http://nepc.colorado.edu/publication/chartering-equity.

- Julie F. Mead, “Devilish details: Exploring features of charter school statutes that blur the public/private Distinction,” Harvard Journal on Legislation 40, no. 2, (2003): 349–94.

- “Authorizing Basics,” National Association of Charter School Authorizers, accessed January 13, 2019, https://www.qualitycharters.org/authorizingmatters/basics/.

- Julie F. Mead, “Devilish details: Exploring features of charter school statutes that blur the public/private Distinction,” Harvard Journal on Legislation 40, no. 2, (2003): 349–94.

- “How do states authorize charter schools? Methods differ greatly study finds,” PewTrusts.Org., December 16, 2015, https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2015/12/16/how-do-states-authorize-charter-schools-methods-differ-greatly-study-finds.

- See, for example, Raiza Giorgi and Victoria Martinez, “SYHS fears insolvency over payments to Olive Grove Charter School,” Santa Ynez Valley Star, January 13, 2019, http://www.santaynezvalleystar.com/syhs-fears-insolvency-over-payments-to-olive-grove-charter-school/.

- For a discussion of the principles and standards recommended by the National Association of Charter School Authorizers, see “Principles and Standards for Quality Charter School Authorizing,” National Association of Charter School Authorizers, September 2018, https://www.qualitycharters.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/NACSA-Principles-and-Standards-2018-Edition.pdf.

- Catherine E. Lhamon, “Dear Colleague Letter on Charter Schools’ Legal Obligations under Federal Civil Rights Law,” United States Department of Education, Office for Civil Rights, May 14, 2014, https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/letters/colleague-201405-charter.pdf.

- Julie F. Mead and Suzanne E. Eckes, “How School Privatization Opens the Door for Discrimination,” National Education Policy Center, 2018, http://nepc.colorado.edu/publication/privatization.

- “Characteristics of Traditional Public Schools and Public Charter Schools,” National Center for Education Statistics, April 2018, https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_cla.asp.

- “Public Charter School Enrollment,” National Center for Education Statistics, March 2018, https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_cgb.asp.

- Ivan Moreno, “US Charter Schools Put Growing Numbers in Racial Isolation,” Associated Press, December 3, 2017, https://apnews.com/e9c25534dfd44851a5e56bd57454b4f5.

- “Characteristics of Traditional Public Schools and Public Charter Schools,” National Center for Education Statistics, April 2018, https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_cla.asp.

- Grover J. Whitehurst, Richard V. Reeves, Nathan Joo, and Edward Rodrigue, “Balancing Act. Schools, Neighborhoods, and Racial Imbalance,” Brookings Institution, November 2017, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/es_20171120_schoolsegregation.pdf.

- Roslyn Arlin Mickelson, Martha Bottia, and Stephanie Southworth, “School Choice and Segregation by Race, Class, and Achievement,” Education Policy Research Unit, March 2008, https://nepc.colorado.edu/sites/default/files/CHOICE-08-Mickelson-FINAL-EG043008.pdf.

- Joseph Oluwole and Preston Green, “Charter Schools: Racial Balancing Provisions and Parents Involved,” Arkansas Law Review 61 (2008): 1–52.

- See National Coalition on School Diversity, “Resource Collection: School Integration after Parents Involved,” https://school-diversity.org/postpicsresources/.

- Julie F. Mead and Suzanne E. Eckes, “How School Privatization Opens the Door for Discrimination,” National Education Policy Center, 2018, http://nepc.colorado.edu/publication/privatization.

- “Status and Trends in the Education of Racial and Ethnic Groups,” National Center for Education Statistics, July 2017, https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2017/2017051.pdf.

- “Education Needs to Further Examine Data Collection on English Language Learners in Charter Schools,” Government Accountability Office, August 2013, https://www.gao.gov/assets/660/655930.pdf.

- Peggy Garcia and P. Zitali Morales, “Exploring Quality Programs for English Language Learners in Charter Schools: A Framework to Guide Future Research,” Education Policy Analysis 24, no. 53 (May 2016), http://dx.doi.org/10.14507/epaa.24.1739.

- “Characteristics of Traditional Public Schools and Public Charter Schools,” National Center for Education Statistics, April 2018, https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_cla.asp.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- “Charter Schools: Additional Federal Attention Needed to Protect Access for Children with Disabilities,” Government Accountability Office, June 2012, https://www.gao.gov/assets/600/591435.pdf.

- Ibid.

- Lauren Rhim and Shaini Kothari, “Key Trends in Special Education in Charter Schools: A Secondary Analysis of the Civil Rights Data Collection,” National Center for Special Education, February 2018, http://static1.squarespace.com/static/52feb326e4b069fc72abb0c8/t/5a8d7e69419202fa34e8f459/1519222386373/280272+NCSECS+Full+Report_WEB.pdf.

- Ibid.

- 29 U.S.C. § 794 (2012); 34 C.F.R. § 104.3(j) (2014). Students protected under Section 504 are likewise protected under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) (42 U.S.C. §§ 12131–12134 (2012); 28 C.F.R. § 35.104 (2014)).

- (20 U.S.C. § 1401(3)(A) (2012); 34 C.F.R. § 300.9 (2014)).

- Lauren Rhim and Shaini Kothari, “Key Trends in Special Education in Charter Schools: A Secondary Analysis of the Civil Rights Data Collection,” National Center for Special Education, February 2018, http://static1.squarespace.com/static/52feb326e4b069fc72abb0c8/t/5a8d7e69419202fa34e8f459/1519222386373/280272+NCSECS+Full+Report_WEB.pdf.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Bruce D. Baker, “Exploring the Consequences of Charter School Expansion in U.S. Cities,” Economic Policy Institute, November 2016, https://www.epi.org/publication/exploring-the-consequences-of-charter-school-expansion-in-u-s-cities/.

- Ibid.

- Gordon Lafer, “Breaking Point: The Cost of Charter Schools in Public School Districts,” In the Public Interest, May 2018, https://www.inthepublicinterest.org/wp-content/uploads/ITPI_Breaking_Point_May2018FINAL.pdf.

- Derek Black, “Preferencing Educational Choice: The Constitutional Limits,” Cornell Law Review 103, no. 6 (2018): 1359–430.

- Ibid., p. 1359.

- David Arsen, Thomas A. DeLuca, Yongmei Ni, and Michael Bates, “Which Districts Get into Financial Trouble and Why: Michigan’s Story,” Education Policy Center at Michigan State University, Working Paper #51, November 2015, http://www.education.msu.edu/epc/library/papers/documents/WP51-Which-Districts-Get-Into-Financial-Trouble-Arsen.pdf.

- Ibid. at 9.

- Ibid., 19.

- Ibid., 20.

- Raiza Giorgi and Victoria Martinez, “SYHS fears insolvency over payments to Olive Grove Charter School,” Santa Ynez Valley Star, January 13, 2019, http://www.santaynezvalleystar.com/syhs-fears-insolvency-over-payments-to-olive-grove-charter-school/.

- Ibid.

- “Nationwide Audit of Oversight of Closed Charter Schools,” United States Department of Education, Office of Inspector General, September 28, 2018, https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/oig/auditreports/fy2018/a02m0011.pdf.

- “Red Flags: Overleveraged Debt,” Grand Canyon Institute, January 9, 2019, http://grandcanyoninstitute.org/red-flags-overleveraged-debt/.

- Preston Green, Bruce Baker, Joseph Oluwole, and Julie Mead, “Are We Heading toward a Charter School “Bubble”? Lessons from the Subprime Mortgage Crisis,” University of Richmond Law Review 50 (2016): 783–808, https://lawreview.richmond.edu/files/2016/03/Green-503.pdf.

- Bruce D. Baker, “Exploring the Consequences of Charter School Expansion in U.S. Cities,” Economic Policy Institute, November 2016, https://www.epi.org/publication/exploring-the-consequences-of-charter-school-expansion-in-u-s-cities/.

- Julie F. Mead and Preston C. Green, “Chartering Equity: Using Charter School Legislation and Policy to Advance Equal Educational Opportunity,” National Education Policy Center, 2012, http://nepc.colorado.edu/publication/chartering-equity.

- Julie F. Mead, “The Role of Law in Educational Policy Formation, Implementation and Research,” in Handbook of Education Policy Research, ed. Gary Sykes, Barbara Schneider, and David N. Plank (New York, NY: Routledge Publishers for the American Educational Research Association, Washington, D.C., 2009), 286–95.

- “Principles and Standards for Quality Charter School Authorizing,” National Association of Charter School Authorizers, September 2018, 6, https://www.qualitycharters.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/NACSA-Principles-and-Standards-2018-Edition.pdf.

- Richard. D. Kahlenberg and Halley Potter, A Smarter Charter: Finding What Works for Charter Schools and Public Education (New York: Teachers College Press, 2014); Richard Kahlenberg and Halley Potter, “Diverse charter schools: Can racial and socioeconomic integration promote better outcomes for students?” The Century Foundation, May 2012, https://www.issuelab.org/resources/12746/12746.pdf; Halley Potter and Kimberly Quick, “Diverse-by-design charter schools,” The Century Foundation, May 15, 2018, https://tcf.org/content/report/diverse-design-charter-schools/; Huriya Jabbar and Terri S. Wilson, “What is diverse enough? How ‘intentionally diverse’ charter schools recruit and retain students,” Education Policy Analysis Archives 26, no. 165 (2018), http://dx.doi.org/10.14507/epaa.26.3883.

- “2017 Recipients,” Schools of Opportunity, National Education Policy Center, accessed September 15, 2018, http://schoolsofopportunity.org/recipients/2017.

- “About Us,” Schools of Opportunity, National Education Policy Center, accessed September 15, 2018, http://schoolsofopportunity.org/.

- Huriya Jabbar and Terri S. Wilson, “What is diverse enough? How ‘intentionally diverse’ charter schools recruit and retain students,” Education Policy Analysis Archives 26, no. 165 (2018), http://dx.doi.org/10.14507/epaa.26.3883.

- These recommendations build on those we made in our earlier work, which also provides draft policy language for those interested. Julie F. Mead and Preston C. Green, “Chartering Equity: Using Charter School Legislation and Policy to Advance Equal Educational Opportunity,” National Education Policy Center, 2012, http://nepc.colorado.edu/publication/chartering-equity.

- “Expanding Opportunities through Quality Charter Schools Program (CSP) Grants to State Entities,” U.S. Department of Education, Office of Innovation and Improvement, accessed December 28, 2018, https://innovation.ed.gov/what-we-do/charter-schools/state-entities/.

- Julie F. Mead and Preston C. Green, “Chartering Equity: Using Charter School Legislation and Policy to Advance Equal Educational Opportunity,” National Education Policy Center, 2012, 16, http://nepc.colorado.edu/publication/chartering-equity.

- Angel v. Bullington, 330 U.S. 183, at 209 (1947).