Editor’s note: In December 2020, TCF published an updated school integration inventory—the most comprehensive to date—which is available here.

Executive Summary

Students in racially and socioeconomically integrated schools experience academic, cognitive, and social benefits that are not available to students in racially isolated, high-poverty environments. A large body of research going back five decades underscores the improved experiences that integrated schools provide. And yet, more than sixty years after Brown v. Board of Education, American public schools are still highly segregated by both race and class. In fact, by most measures of integration, our public schools are worse off, since they are now even more racially segregated than they were in the 1970s, and economic segregation in schools has risen dramatically over the past two decades.

In this report, we highlight the work that school districts and charter schools across the country are doing to promote socioeconomic and racial integration by considering socioeconomic factors in student assignment policies.

Key findings of this report include:

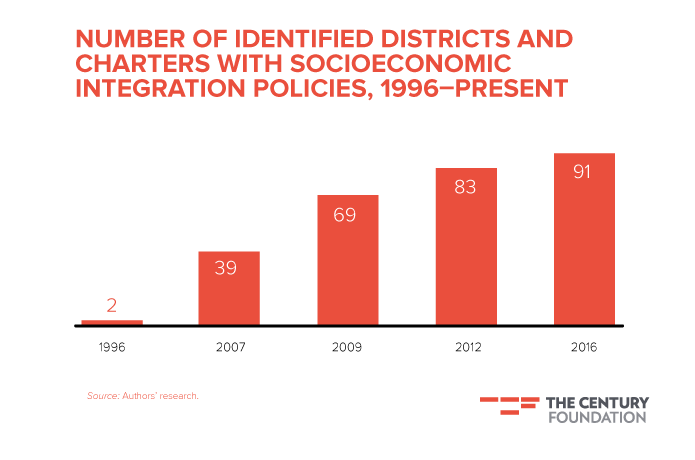

- Our research has identified a total of 91 districts and charter networks across the country that use socioeconomic status as a factor in student assignment. When The Century Foundation (TCF) first began supporting research on socioeconomic school integration in 1996, it could find only two districts that employed a conscious plan using socioeconomic factors to pursue integration. In 2007, when TCF began compiling a list of class-conscious districts, researchers identified roughly 40 districts that used student socioeconomic status in assignment procedures. Nine years later, TCF has found that figure has more than doubled, to 91, including 83 school districts and 8 charter schools or networks.

- The 91 school districts and charter schools with socioeconomic integration policies enroll over 4 million students. Roughly 8 percent of all public school students currently attend school districts or charter schools that use socioeconomic status as a factor in student assignment.

- The school districts and charter networks identified as employing socioeconomic integration are located in 32 different states. The states with the greatest number of districts and charters on the list are California, Florida, Iowa, New York, Minnesota, and North Carolina.

- The majority of districts and charters on the list have racially and socioeconomically diverse enrollments. All but 10 districts and charter schools on the list have no single racial or ethnic group comprising 70 percent or more of the student body. All but 17 of the districts and charters have rates of free or reduced price lunch eligibility that are less than 70 percent.

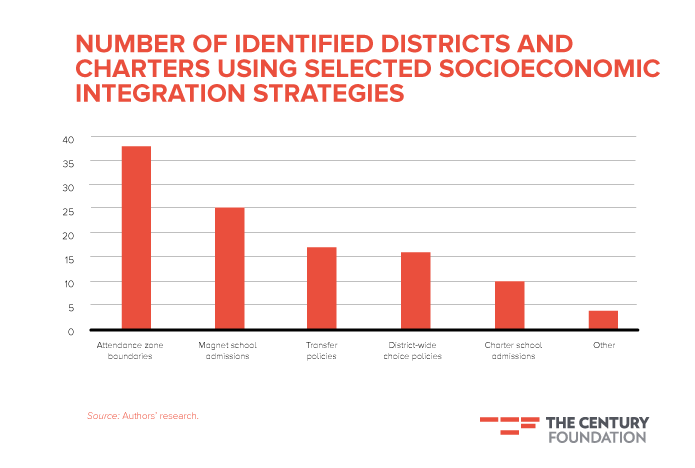

- The majority of the integration strategies observed fall into five main categories: attendance zone boundaries, district-wide choice policies, magnet school admissions, charter school admissions, and transfer policies. Some districts use a combination of methods. The most common strategy for promoting socioeconomic integration used by districts and charters on our list is redrawing school attendance boundaries, observed in 38 school districts; 25 districts include magnet schools that consider socioeconomic status in their admissions processes; 17 districts have transfer policies that consider socioeconomic status; 16 districts use some form of district-wide choice policies with explicit consideration of diversity in the design of these programs; and 10 charter networks and school districts have charter school lottery processes that consider socioeconomic status in order to promote diverse enrollment.

The push toward socioeconomic and racial integration is perhaps the most important challenge facing American public schools. Segregation impedes the ability of children to prepare for an increasingly diverse workforce; to function tolerantly and enthusiastically in a globalizing society; to lead, follow, and communicate with a wide variety of consumers, colleagues, and friends. The democratic principles of this nation are impossible to reach without universal access to a diverse, high quality, and engaging education.

The efforts of the districts and charters we identified provide hope in the continuing push for integration, demonstrating a variety of pathways for policymakers, education leaders, and community members to advance equity.

Introduction

More than sixty years after Brown v. Board of Education, American public schools are still highly segregated by both race and class. The signs of separate and unequal education are visible today in small and large ways. In Washington, D.C., a public school with 11 percent low-income students and one with 99 percent low-income students are located just a mile apart.1 In New York City, a metropolis with 4 million white people, a Latina high school student may have to wait until college to meet her first white classmates.2 In Pinellas County, one of the most affluent communities in Florida, a 2007 ordinance creating “neighborhood schools” dismantled decades of desegregation efforts and created a pocket of high-poverty, racially isolated, under-resourced schools that have become known as “failure factories.”3 Sadly, the examples of this persistent problem go on.

As Americans consider the consequences of an education system that increasingly sorts students by race and class, it is also important to recognize the efforts of school districts and charter schools that are attempting to find another path.

In New York City, for example, parents and advocates at half a dozen elementary schools successfully fought for new admissions lottery procedures to promote diversity.4 In Eden Prairie, Minnesota, a superintendent and a group of Somali refugee parents led the charge to create more equitable school boundaries.5 And in Rhode Island, the mayor of an affluent suburban town spearheaded legislation to create regionally integrated charter schools that would draw students from rich suburbs and struggling cities together in the same classrooms.6 These efforts, along with other examples from across the country, demonstrate that there are a variety of approaches available to policymakers, education leaders, and community members committed to advancing equity and integration.

The report begins with background on school segregation, and the remedying role that integration strategies based on socioeconomic status can play. Building on research that The Century Foundation (TCF) has released throughout the past decade, the report then presents our latest inventory of school districts and charter schools that are using socioeconomic integration strategies—outlining our methodology, examining the characteristics of the districts and charters included, and explaining the main types of integration methods encountered.

The efforts of these districts and charter schools range in size and strategy, but their stories all provide hope in the continuing push for integration and equity.

School Segregation Trends—and the Damage Caused

By most measures, our public schools are more racially segregated now than they were in the 1970s.7 Nationwide, more than one-third of all black and Latino students attend schools that are more than 90 percent non-white. For white students, these statistics are reversed: more than a third attend schools that are 90–100 percent white.8

Part of the reason for this surge in racial segregation is that American communities are increasingly stratified by social class. Research from TCF fellow Paul Jargowsky finds that while the percentage of American neighborhoods suffering from concentrated poverty dropped throughout the 1990s, this trend has reversed, having steadily risen since 2000.9 As a result, America’s public schools have also become more economically stratified. A 2014 study found that economic segregation between school districts rose roughly 20 percent from 1990 to 2010, while segregation between schools within a district also grew roughly 10 percent.10

Increasing socioeconomic and racial stratification of schools is also a result of changing education policies. As busing-based integration efforts largely ended in the early 1980s and courts began to severely limit districts’ ability to use racial and ethnic identifiers to achieve demographic balance, most communities gradually returned to so-called neighborhood schools that tether school attendance zones to real estate. Today, many higher income families who have purchased high-property-value homes in certain districts feel as if their child deserves to attend the school that they shopped for through the housing market, regardless of the implications for children whose families cannot access those spaces.

Socioeconomic and racial segregation have become related and often overlapping phenomena—a trend that the Civil Rights Project calls “double segregation.”11 Schools with mostly black and Latino students also tend to be overwhelmingly low-income.12 At the kindergarten level, for example, a majority of black and Latino students attend schools with more than 75 percent non-white classmates and high average poverty rates. However, most white kindergartners, even those from poor families, attend schools with mostly middle-class, white classmates.13 We see related patterns in housing: poor black and Hispanic families are more likely than poor white families to live in neighborhoods with the most extreme poverty.14

This stark segregation has profound negative implications for student outcomes. A large body of research going back five decades finds that students perform better academically in racially and socioeconomically integrated schools than in segregated ones. Students in integrated schools have been shown to have stronger test scores and increased college attendance rates compared to similar peers in more segregated schools.15 In the words of one 2010 review of fifty-nine rigorous studies on the relationship between a school’s socioeconomic and racial makeup and student outcomes in math, the social science evidence on the academic benefits of diverse schools is “consistent and unambiguous.”16 Furthermore, research shows that students in racially diverse schools have improved critical thinking skills and reduced prejudice, and they are more likely to live in integrated neighborhoods and hold jobs in integrated workplaces later in life.17 Students in racially segregated, high-poverty schools, however, face lower average academic achievement and miss out on these important civic benefits.

The Role for Socioeconomic Integration Strategies

The policy implication of the intertwined racial and economic segregation of public schools is that school integration strategies moving forward should address both racial and socioeconomic aspects of segregation. Historically, school integration efforts have focused on race, but for more than a decade, TCF has examined the role that socioeconomic considerations can play, not only in advancing integration but also in improving achievement.18 This study of school districts and charter networks that use socioeconomic status as one of the levers for achieving school integration is TCF’s most recent—and most ambitious—catalog of the progress being made in this area.

All of the districts and charters included in our study directly consider socioeconomic balance in at least some of their student assignment decisions. Some of the districts and charters studied also directly consider race. And many of the districts and charters have integration goals that include both racial and socioeconomic integration—even when socioeconomic status is the sole factor considered in student assignment.

Our reasons for focusing on socioeconomic integration strategies—whether used alone or in combination with racial integration approaches—are educational, legal, and practical. To begin with, socioeconomic integration is important in its own right for promoting educational achievement. In 1966, the federally commissioned Coleman Report found that the social composition of the student body was the most influential school factor for student achievement,19 and dozens of studies since then have yielded similar findings.20 As journalist Carl Chancellor and our colleague Richard Kahlenberg have noted, “African American children benefited from desegregation . . . not because there was a benefit associated with being in classrooms with white students per se, but because white students, on average, came from more economically and educationally advantaged backgrounds.”21

While the research on the important roles played by students’ own socioeconomic status and by the socioeconomic mix in a school is clear, socioeconomically driven educational inequities continue to grow. In the fifty years since the Coleman Report, the economic achievement gap has grown, even as racial achievement gaps have narrowed. Today, the gap in average test scores between rich and poor students (those in the ninetieth and tenth percentiles by income, respectively) is nearly twice the size of the gap between white and black students.22

Efforts to address racial and socioeconomic segregation using income as a targeting metric also have the advantage of avoiding the recent legal threats to race-based integration plans. The U.S. Supreme Court’s 2007 decision in Parents Involved in Community Schools vs. Seattle School District No. 1 limited options for voluntarily considering race in K–12 school integration policies, absent legal desegregation orders. Based on joint guidance from the U.S. Department of Justice and the U.S. Department of Education in response to the ruling, school districts may voluntarily adopt race-based integration strategies, using either generalized or individual student data, under certain circumstances. However, school districts are required first to consider whether workable race-neutral approaches exist for achieving their integration goals.23 In some cases, socioeconomic approaches will be sufficient to achieve racial integration benchmarks. Because of the intersections between race and class, socioeconomic integration at the K–12 level may also produce substantial racial integration, depending on the strength of the plan and the characteristics of the district.24 Furthermore, if districts do turn to race-based strategies, they will typically be required to consider socioeconomic factors as well.25

Of course, desegregation battles continue to be fought in the courts, addressing racial segregation head-on. In 2015, for example, families in Minnesota’s Twin Cities filed a new racial segregation suit against the state, twenty years after a similar suit was filed; a federal appeals court pushed for a stronger integration plan in a case dating back to 1965 to desegregate schools in Cleveland, Mississippi; and a new settlement was reached in Connecticut’s major state desegregation case Sheff v. O’Neill, first filed in 1989.26 But, as these recent examples show, the legal path to desegregation is a long one.

If we are to make meaningful strides toward increased school integration—by both race and social class—we need policymakers and communities to adopt voluntary integration plans alongside ongoing desegregation litigation. Thus, we believe that socioeconomic strategies will be important practical solutions for school districts or charter schools considering integration policies now or in the near future.

Creating an Inventory of Socioeconomic Integration Policies

We identified ninety-one school districts and charter schools or networks that have implemented socioeconomic integration strategies. The school districts and charter schools employing these strategies educate roughly 4 million students in all. In this section, we begin by describing our methodology for collecting information on integration strategies used by districts and charters. We then offer an overall portrait of the number, size, location, and demographics of the different districts and charters on the list. Finally, we describe the major types of integration strategies we identified and discuss the different measures of socioeconomic status being used.

Because there is no standard definition of what constitutes a socioeconomic integration policy, nor a centralized source for information on such policies, we describe in depth below our criteria for deciding which districts and charter schools to include, our sources for information on integration policies, and the legal limitations of our work.

Criteria for Inclusion

In constructing our list, we chose to focus on districts and charter networks that have established policies or practices accounting for some measure of socioeconomic status in student school assignment. While the intent behind these actions is to create demographically balanced school buildings, our research does not focus on whether balance was truly achieved. That question is an important topic for future research but beyond the scope of this report. Rather, this inventory acknowledges those districts who have taken meaningful steps, of whatever size, toward socioeconomic integration.

For the most part, the integration policies on our list are intradistrict in nature: controlled by a single school district or charter school network, and limited to the geographic and population boundaries of one district. Although intradistrict integration is the most popular mode of operation, many geographic regions find that the strongest barriers to integration by race and class are found between, rather than within, districts. Indeed, nationwide, more than 80 percent of racial segregation in public schools occurs between rather than within school districts.27 In response to this challenge, some interdistrict integration plans do exist, in which students can cross district lines in order to balance school demography, and we have included these plans when they consider socioeconomic factors.28 Although, by definition, interdistrict agreements involve several participating school districts, our list only includes the major urban district involved in an agreement, as a much smaller number of students in suburban districts are affected.

Furthermore, very few of the districts in our list apply socioeconomic integration methods to every school in the district. Efforts range in scope and size. We chose to include any districts that account for socioeconomic status in at least a portion of the school assignment and admissions procedures.

We also chose to include only districts or charters where integration strategies are currently affecting student assignment in some way—either through present policies or sufficiently recent rezoning efforts.29 Districts or charters that have had socioeconomic integration plans in the past, but no longer adhere to these policies, are not included.

Sources and Verification of Information

As in previous TCF reports looking at districts that use socioeconomic class to integrate their schools—such as those released in 2007, 2009, and 201230—we followed a similar process, constructing our lists from a combination of Internet and news searches, leads from integration advocates and other researchers, and past inquiries from districts seeking information to establish or sustain their own programs.

Other than the information TCF previously collected, there is very limited data on school districts that employ socioeconomic integration strategies—or racial integration strategies, for that matter. This gap is likely due to the difficulty in locating good sources. Information on court-ordered and voluntary integration plans—our list contains both—is not stored in a central location. Education journalists Rachel Cohen and Nikole Hannah-Jones both discuss the frustrating process of determining which districts remain under federal desegregation orders. Hannah-Jones estimates that there are roughly 300 school districts with active desegregation orders, yet many school districts “do not know the status of their desegregation orders, have never read them, or erroneously believe that orders have ended.” Hannah-Jones later explains that federal courts and regulatory agencies are sometimes as disorganized as the districts that they oversee, not always aware of the desegregation orders that remain on court dockets and not consistently monitoring or enforcing those districts that should legally remain under supervision.31 Cohen attributes this not only to poor record keeping and “a lack of consistent court oversight,” but to unclear legal understandings of what it means to be “unitary”—the designation currently given to districts once they meet certain desegregation criteria, which only arose in 1991, well after many districts had previously been released from federal desegregation orders without meeting that standard.32

Erica Frankenberg, an assistant professor of education policy at Pennsylvania State University, encountered similar challenges when attempting to construct a list of districts pursuing voluntary integration. Policies pertaining to integration efforts proved difficult to locate; many policies are not accessible online, and districts modify, augment, or rescind policies with some regularity.33

A large component of our own research process involved contacting each of the districts and charter networks for which we had evidence of socioeconomic integration. After asking for review of (and if necessary, corrections or additions to) our information, about 40 percent of the contacted districts responded to our inquiries; several were eager to speak with us in great detail about their policies and our research, while others were more conservative with the information they provided. The overwhelming majority of the school officials with whom we spoke were either superintendents, charter school directors, deputy superintendents, or enrollment managers. In cases where we did not receive a response from contacted officials, we included the districts or charters on the list if we were satisfied with evidence in the public record that they had implemented a socioeconomic integration strategy.

During the research process, our interactions with many district officials revealed that socioeconomic school integration is still often a fragile political issue, limiting administrators’ desire to publicly discuss the existence and success of assignment plans or other programs that promote integration. The term integration itself—once a powerful call for social justice in our school system that was often met by an equally powerful backlash—continues to elicit strong emotions, ones that find their most powerful influence in school board politics. Because school board members are typically elected, they are understandably sensitive to the desires and concerns of voters who benefit from and promote segregated systems. This rather prevalent mindset likely explains why specific information about assignment plans that disrupt this pattern is often inaccessible online or in public record, and why many officials are hesitant about providing details of their plans. Furthermore, some district and charter leaders may believe it is in the best interest of their integration strategies to operate under the radar rather than attract attention that may subject them to renewed scrutiny. We believe, however, that we cannot make progress on integration as a nation without understanding the efforts currently underway and providing that information as a resource to others.

The determination of whether or not a district should be included on the list was made based on information gathered through direct contact with districts and publicly verifiable information. Because of this process required such labor-intensive validation, it is possible that there are districts that consider class factors in student assignment that are not represented on our list. We welcome any new information from anyone reviewing this document.

Socioeconomic Integration Policies by the Numbers

When TCF first began supporting research on socioeconomic school integration in 1996, we found only two districts (La Crosse School District in Wisconsin and McKinney Independent School District in Texas) that employed a conscious plan using socioeconomic factors to pursue integration. In 2007, when TCF first began compiling a list of class conscious districts, researchers identified roughly 40 districts that used student socioeconomic status in assignment procedures. Nine years later, our research has identified a total of 91 districts and charter networks (see Figure 1) that employ such policies and procedures. The districts and charters range in size from recently founded Compass Charter School in Brooklyn, with just over 100 students, to Chicago Public Schools, with nearly 400,000 students. In total, 4,005,862 students currently attend school districts or charter schools that use socioeconomic status as an assignment factor—representing roughly 8 percent of total public school enrollment.34 These students attend a total of 6,546 schools.

Figure 1.

TCF’s inventory of integration-seeking schools and districts has changed in a few notable ways since its inception. The most recent previous list, released in 2012, contained 80 districts and charters, which together enrolled 3,978,587 students. Our expanded list of 91 districts and charters enrolling over 4 million students demonstrates a steady rise in popularity in socioeconomic integration programs. Most of the school districts that adopted plans in 2013 or later were in larger, more metropolitan centers, such as Denver, Newark, Nashville, St. Paul, and the District of Columbia, among others. Notably, the large school district of Wake County, North Carolina returned to our list after progressives won a political fight and replaced an anti-integration school board with more sympathetic leadership; a new policy aimed at minimizing concentrations of poverty in Wake County schools was established in 2013.35 At the same time, some districts, such as Seattle Public Schools, that formerly had socioeconomic integration plans dropped their efforts. After Seattle Public Schools’ racial integration program was struck down by the U.S. Supreme Court in 2007, the district made some efforts to consider socioeconomic factors when drawing school assignment boundaries, but since abandoned those efforts in subsequent redistricting.36 However, in general, the vector is pointing in the direction of progress, as we identified in our study more new districts and charters with socioeconomic integration plans than districts that have abandoned efforts.

Our list consists mostly of school districts; however, of the 91 entries in our list, 6 are individual charter schools or charter school networks. (Charter schools are public schools of choice operated by private entities rather than by traditional public school boards.) Because charters are allowed increased flexibility in curriculum and admissions procedures, and because charters typically accept students from multiple school zones or neighborhoods, they are well positioned—in theory—to facilitate student integration through weighted lottery systems and targeted outreach.

The school districts and charter networks employing socioeconomic integration that we identified are located in 32 different states (see Figure 2). The most represented states are located throughout the continental United States and maintain different political orientations. They are: California (12), Florida (10), Iowa (7), New York (6), Minnesota (6), and North Carolina (5).

Figure 2.

Locations of Identified Districts and Charters with Socioeconomic Integration Policies

Source: Authors’ research.

Demographics of Districts and Charters with Socioeconomic Integration Plans

Our sample of students enrolled in districts and charters with integration programs is slightly more racially diverse than national averages. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, in the 2012–13 school year (the most recent year of data available), 51 percent of all students enrolled in public schools were non-Hispanic white, 16 percent black, 24 percent Hispanic, 5 percent Asian/Pacific Islander, 1 percent American Indian, and 3 percent two or more races or other. Across the population of all students enrolled in districts and charters in our inventory, there was no clear racial majority: 32 percent of the students were white, 26 percent were black, 31 percent were Hispanic, 6 percent were Asian/Pacific Islander, less than 1 percent were American Indian, and about 5 percent were two or more races or other.37

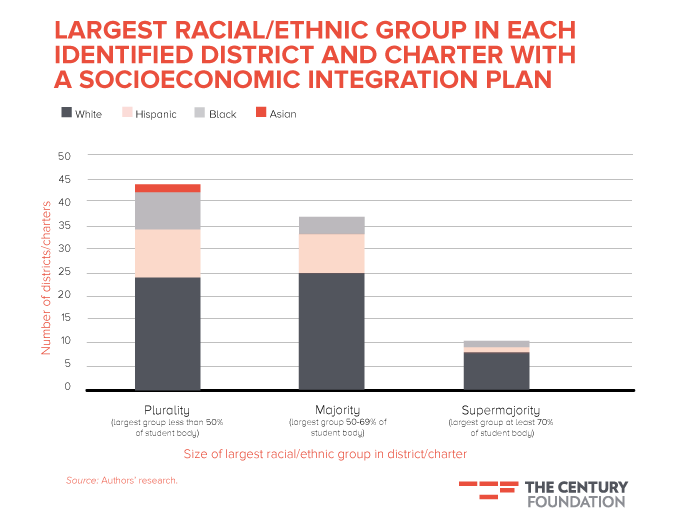

In most of the identified districts and charters, white students are the largest racial group in the school system. Thirty-three of the 91 districts and charters are majority white, and an additional 24 districts have student populations where whites are a plurality. Five districts are majority black, and black students comprise a plurality in another 8 districts. Hispanic children constitute a clear majority in 9 districts and a plurality in 10 others, while Asian students formed a plurality in an additional 2 school districts (see Figure 3).

Figure 3

Social scientists and education researchers sometimes use enrollment at or above 70 percent of a single racial or ethnic group as a threshold for measuring racial isolation. At this high level of racial homogeneity, research has shown that it becomes increasingly difficult for minority children to achieve a sense of belonging, and it is more challenging to encourage tolerance and cross-racial friendships among all students.38 Based on this measure, 81 of the 91 districts and charter schools on our list are racially diverse, with no single racial or ethnic group comprising 70 percent or more of the student body. Of the 10 districts that have a racial supermajority of at least 70 percent enrollment, 8 are predominantly white, 1 is predominantly Hispanic, and 1 is predominantly black.

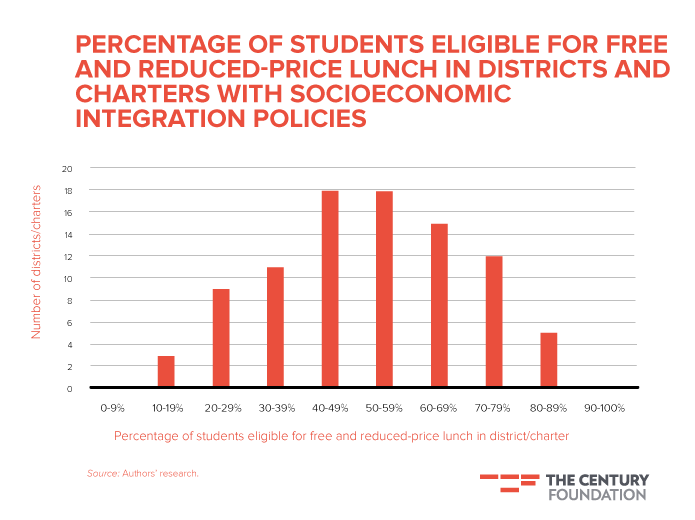

Poverty in schools remains a sizable problem, and the numbers of students eligible for the free or reduced price lunch program (the most commonly used indicator of low-income student status) continues to increase. Nationally, during the 2012–13 academic year, just over 50 percent of all public school students in the United States were eligible for the free or reduced price lunch program.39 As a whole, the districts and charters on our list had slightly higher levels of economic disadvantage. Fifty-nine percent of all students enrolled in the districts and charter schools in our inventory were eligible for free or reduced price lunch. The median enrollment of eligible students was 54 percent, and two-thirds of the districts and charters fell within a range of 30–69 percent eligible. The rate of free or reduced price lunch eligibility is at least 70 percent in seventeen of the districts in our inventory (see Figure 4).

Figure 4

In summary, the majority of districts and charters on our list have racially and socioeconomically diverse enrollment (defined here as having less than 70 percent of students from a single racial or ethnic group and less than 70 percent of students who are low-income).

In the school districts with high levels of poverty or racial homogeneity, however, merely balancing enrollment will still leave schools with low levels of racial diversity and high levels of poverty. Creating racially diverse, economically mixed schools in these districts typically requires using interdistrict enrollment strategies or focusing integration efforts on particular neighborhoods or schools with the greatest potential for reaching diversity goals. For example, Chicago Public Schools, where 86 percent of the students are eligible for free or reduced price lunch, limits its integration efforts to its selective high schools and magnet programs. Denver Public Schools, with 72 percent of students eligible for free or reduced-price lunch, targets its integration efforts on strategically placed geographic zones that include both low and high income neighborhoods. And Hartford Public Schools creates integrated school options for a student body that is 85 percent low-income through extensive interdistrict magnet school and transfer programs.

Methods of Integration

The districts that we identified as pursuing socioeconomic integration used a variety of different approaches, and some districts used a combination of methods. The majority of these strategies fell into five main categories: attendance zone boundaries, district-wide choice policies, magnet school admissions, charter school admissions, and transfer policies (see Figure 5). The first two categories—altering attendance zone boundaries or implementing district-wide choice policies—have the greatest potential to create integration in all or most schools across a district. However, the other three main approaches—factoring diversity into magnet school admissions, charter school admissions, or transfer policies—are also important steps in increasing integration and can be highly effective at the school level. Below we describe each of these socioeconomic integration methods.

Figure 5

Attendance Zone Boundaries

The most common strategy for promoting socioeconomic integration used by districts and charters on our list was redrawing school attendance boundaries. We identified thirty-eight school districts that have redrawn attendance boundaries with socioeconomic balance among schools as a factor. The oldest example that we found of a school district seeking socioeconomic integration is La Crosse School District in Wisconsin, which in 1979 moved the boundary line for its two high schools to increase socioeconomic balance.40

The reason that redrawing attendance zones is the most common method of socioeconomic integration on our list is likely because it most easily fits with existing enrollment protocols. School enrollment based on assigned zones is the reality in most school districts across the country. Nationwide, 82 percent of all children in public schools attend their assigned school (compared to just 18 percent attending a district, magnet, or charter schools as a result of choice).41 In addition, one of the benefits of this approach to integration is that it has the potential to affect all schools in the district—particularly if a school board adopts a resolution to make socioeconomic balance a consideration in all redistricting decisions moving forward.

However, there are also limitations and challenges to a boundary-based integration strategy. School boundaries usually need to be readjusted regularly as populations and demographics shift in response to housing patterns. School boundary decisions are also almost always politically contentious. Families frequently buy or rent homes with particular schools in mind and may object to changes in school assignment that they view as forced. The rezoning process can be challenging even when integration is not a consideration. Bringing questions about socioeconomic and racial integration into the conversation can unleash a host of parent concerns and anxieties.

In Eden Prairie, Minnesota, for example, the decision to redraw elementary school boundaries in order to create more racially and socioeconomically integrated schools in 2010 led to community backlash that culminated with the ousting of the superintendent who had led those efforts.42 But five years later, those boundaries remain in effect, and students are more evenly distributed by income.43 In 2010, the district’s neighborhood elementary schools ranged from 9.5 percent to 42.1 percent of students eligible for free and reduced-price lunch—a gap of 32.6 percentage points. As of 2015, this gap had shrunk by more than a third, with all neighborhood elementary schools falling between 20 percent and 40 percent of students eligible for free and reduced-price lunch.44

In other districts, encouraging socioeconomic integration through boundary reassignments has been a smoother process. The school board of McKinney Independent School District (MISD) outside Dallas, Texas, passed a policy back in 1995 that socioeconomic diversity should be a consideration in school zoning decisions, particularly at the middle and high school level. Twenty years and multiple rezoning processes later, the schools are relatively economically balanced at the middle and high school level. The rezoning process is never easy, but McKinney has kept its commitment to making socioeconomic integration part of these conversations. In a statement released in response to a recent high school rezoning process, the district admitted that not everyone would be satisfied with the outcome, but maintained a commitment to socioeconomic balance. “Changing schools is an emotional issue for all involved and is an inevitable issue to be addressed frequently in a growing school district like MISD,” the press release stated. “Our guiding principle is to provide the best and most equitable opportunities for all children.”45

District-wide Choice Policies

The other main approach for pursuing integration across all or many schools in a district, rather than redrawing attendance boundaries, is to shift enrollment to a choice-based policy, with explicit consideration of diversity in the design of the program. We identified sixteen school districts that use some form of district-wide choice policies that consider diversity.

Considering diversity a goal when designing a controlled choice program is important, since research shows that choice alone is usually not enough to produce integration, and in fact can actually increase school segregation.46 Districts with choice programs that effectively promote integration typically have clear diversity goals for student enrollment; devote resources to student recruitment and family engagement, particularly targeting low-income families and others who may have less access to information about schools through their social networks; monitor diversity during the school application phase and adjust recruitment strategies as needed; consider socioeconomic factors in the algorithm for assigning students to schools; and/or invest in new programming to attract students of different backgrounds to apply to schools that are currently less diverse.

In the most robust examples of these equitable choice programs, districts shift entirely away from student assignment based on geographic zones to a system in which all families rank their choices of schools from across the district (or within a certain geographic area, in larger districts). Schools implement magnet or themed programs, giving families a reason to select schools outside of their neighborhoods based on pedagogy or course offerings. Some families might still place the greatest priority on a school within walking distance, whereas others might be happy to travel for a STEM or Montessori program, for example. Students are then assigned to schools based on their preferences and an algorithm that ensures a relatively even distribution of students by socioeconomic status across all schools. Algorithms may weigh factors such as family income and parent educational attainment on an individual student basis or through geographic proxies based on a student’s neighborhood or home address.

This enrollment model, often known as “controlled choice,” was first implemented in Cambridge, Massachusetts, as a tool for racial integration in 1981, and has since been used to promote both racial and socioeconomic integration goals.47 Districts with controlled choice policies that weigh socioeconomic factors include Cambridge Public School District in Massachusetts; Champaign Unit 4 Schools in Illinois; St. Lucie Public School District, Lee County Public Schools, and Manatee County School District in Florida; Berkeley Unified School District in California; Montclair Public Schools in New Jersey; Rochester City School District and White Plains Public Schools in New York; and Jefferson County Public Schools in Kentucky.

Controlled choice has the advantage of being able to promote integration in schools across a district, with an enrollment strategy that remains effective even as demographics in a district shift. And giving families choice can help to create support for the program. In Champaign Unit 4 Schools in Illinois, for example, 80–90 percent of families typically receive their first choice school during the kindergarten enrollment process.48 Perhaps the biggest objection to a controlled choice approach to integration is that, under its purest form, families no longer have a guarantee that their child will be admitted to a specific school—and they cannot plan for that when choosing a home. But on the flipside, controlled choice allows students to stay in their school even if families move elsewhere in the district. Sibling preferences can also enhance the predictability of the student assignment process for families with multiple children. And the loss of this predictability comes in exchange for an increase in choice. Parents may not know when their child is four years old what school she will attend the following year, but they will have the flexibility to rank schools that they think will be best for her learning style and their family preferences—whether that be an arts elementary school a bus ride away or a dual language school across the street.

We also identified district-wide choice plans that fell short of the clear diversity goals and algorithms of controlled choice but which nonetheless have notable provisions to promote integration. San José Unified School District in California; Newark Public Schools in New Jersey; Eugene School District in Oregon; San Francisco Unified School District in California; St. Paul Public School District in Minnesota; and Denver Public Schools in Colorado all have options for choice-based enrollment across the district, sometimes in combination with neighborhood assignment, which include provisions to promote diversity in at least some schools.

Magnet School Admissions

A number of school districts also contain magnet schools that specifically consider socioeconomic diversity in admissions. Today, the term magnet school is used to describe a wide variety of schools with particular themes and choice-based admissions, drawing students from across a geographic area. Some magnet schools have selective admissions based on academic criteria or auditions, with the mission of bringing together the best and brightest students and no clear goals around diversity. But many more magnet schools are part of a different tradition based on desegregation rather than selectivity.

Starting in the late 1960s, school districts began creating magnet schools as tools for choice-based desegregation.49 Under this integrated magnet school model, new schools are created—or old schools are converted—to have distinct pedagogical or curricular themes designed to attract families to apply. These magnet schools strive to reach specific desegregation goals. And by picking themes that appeal to a broad range of families, enrolling students from across a district or multiple districts, and factoring diversity into the admissions lottery, magnet schools can enroll socioeconomically and racially integrated student bodies in school districts with high levels of segregation in neighborhood schools. Research on magnet schools with successful integration plans has shown strong academic outcomes for the students who win the chance in an admissions lottery to attend a socioeconomically and racially diverse magnet school.50

Because the term magnet school is now used to describe a wide variety of schools with particular themes and choice-based admissions, some of which may play no desegregating function, we have only considered those examples of magnet schools that explicitly consider socioeconomic diversity in admissions as examples of clear integration strategies to include in this list. We also did not include magnet schools that have diversity as part of their mission statement or that consider diversity in recruitment unless they also had clear admissions processes to support diverse enrollment. Research suggests that magnet models without admissions processes that prioritize diversity frequently do not create substantial increases in a school’s socioeconomic diversity.51

We identified twenty-five districts with magnet schools that consider socioeconomic status in their admissions processes. Some of these districts, such as Boulder Valley School District in Colorado, have just one magnet school with an admissions policy that considers socioeconomic status, whereas other districts, such as Duval County Public Schools in Florida, contain dozens of magnet schools with diversity-conscious admissions. In most cases, these magnet schools operate within a district, but some of the districts, such as Hartford Public Schools and New Haven Public Schools in Connecticut, operate interdistrict magnet schools enrolling students from urban and suburban districts.

Charter Schools Admissions

Charter schools—which are publicly funded but privately operated—typically have the freedom, like magnet schools, to adopt different educational approaches and enroll students from a geographic area larger than a typical neighborhood attendance zone. For these reasons, charter schools can also promote integration, if designed to do so. In A Smarter Charter: Finding What Works for Charter Schools and Public Education, Richard D. Kahlenberg and Halley Potter argue that the charter sector as a whole has had a segregating effect on public schools, but also highlight specific examples of charter schools that have successfully created integrated enrollment through clear diversity goals, recruitment strategies, and admissions processes.52

As with magnet schools, we cataloged only those charter schools that directly consider socioeconomic diversity in admissions. We identified six charter networks and two individual charter schools with lottery processes that consider socioeconomic status in order to promote diverse enrollment. We also identified two school districts—Santa Rosa City Schools in California and District of Columbia Public Schools in Washington, D.C.—that adopted centralized policies for charter school admissions to reserve seats for low-income or at-risk students in charter schools that otherwise had below-average enrollment of these groups.

It is worth noting that—again, as with magnet schools—some charter schools were left off the list because they do not directly consider diversity in admissions. These schools may still have integration as an intentional part of their mission, and may successfully enroll socioeconomically and racially diverse student bodies, using targeted recruitment, strategic location, and intentional program design to achieve integrated enrollment. In some cases, charter schools have to pursue these methods for the simple fact that they are not legally allowed to use a weighted lottery.53 While these charter schools are not included in this list, examples are profiled in A Smarter Charter, and more than two dozen charter schools and networks are currently members of the National Coalition of Diverse Charter Schools, a grassroots group formed in 2014.54

Transfer Policies

School districts with transfer policies that consider socioeconomic diversity generally give preference to school transfer requests that would increase the socioeconomic diversity of affected schools, or give a priority to economically disadvantaged students when reviewing transfer requests. As with magnet- and charter-based strategies, an integration approach based on transfer policies is not likely to promote integration in all schools across a district. However, policies to encourage integration goals through school transfers can provide an important check on open enrollment policies.

As of 2007, nearly every state had passed an open enrollment law allowing students to apply for interdistrict transfer; that is, between school districts. As of 2011, thirty-two states also had passed intradistrict transfer laws, allowing families to transfer to other schools within a district. And since 2001, all districts nationwide have been required under the federal No Child Left Behind Act to provide intradistrict transfer options for Title I students in failing schools.

Research shows, however, that transfer programs that do not explicitly pursue socioeconomic diversity actually wind up making matters worse. The majority of interdistrict transfers through open enrollment laws serve to increase school segregation, on average, because the students using this option tend to be relatively more advantaged students trg out of low-performing districts.55 Research on intradistrict transfers similarly finds that more-advantaged students are more likely to participate.56

We identified seventeen districts with transfer policies that consider socioeconomic status. Four of these districts have policies designed to increase socioeconomic integration in both inter- and intradistrict transfers, eight have policies applying to intradistrict transfers only, and five have policies addressing interdistrict transfers only.

Measures of Socioeconomic Status

When seeking to manage enrollment, one of the most important questions schools face is how to measure socioeconomic status. Districts and charters striving to create greater socioeconomic integration have to decide whether to look at individual student information, or rely on neighborhood-level data. They then must figure out whether they can simply use data that is already collected and available to them, or how they can collect additional information, if needed.

The majority of the districts and charter schools we identified used data on eligibility for the federal free and reduced-price lunch program—whether at the student, school, or neighborhood level—as the only or main marker for socioeconomic status. This is not surprising, as free and reduced-price lunch eligibility is the main measure of socioeconomic status used throughout education policy and research. Although a small number of districts have faced legal questions about the use of free and reduced-price lunch information in recent years, considering students’ eligibility for the federal school lunch program remains a tried and true method of factoring socioeconomic status into student assignment (see Box 1).

However, there are important and increasing limitations to using free and reduced-price lunch as a socioeconomic marker. Eligibility for the federal school lunch program is determined based solely on family income. Children from families earning up to 130 percent of the poverty line are eligible for free lunch, and those earning 130–185 percent of the federal poverty line are eligible for reduced-price lunch.57 Thus, free and reduced-price lunch eligibility is a blunt measure based on one factor only (family income), and it divides students into just two or three categories, depending on whether free versus reduced-price eligibility is disaggregated. In addition, the data is self-reported, and therefore not always accurate. One study found that 15 percent of school lunch applicants received benefits greater than their eligibility, while 7.5 percent received less than their actual eligibility.58 Research also shows that eligibility for high school students is typically underreported, due to the social stigma that develops around being perceived by peers as poor.59 Finally, individual students’ free and reduced-price lunch eligibility is becoming less available as more schools use the “Community Eligibility Provision” for providing free meals. In 2010, Congress approved a new process to allow whole schools or entire districts to qualify for free meals for all students by meeting a certain number of other criteria based on the percentage of students participating in other public assistance programs.60 In schools or districts using this option, families no longer have to fill out forms for the federal lunch program, meaning that eligibility for the program is no longer an available marker of individual students’ socioeconomic status or a useful measure of school poverty levels (since schools that might have before had 70 percent of students eligible will now show up as 100 percent eligible).61

For these reasons, the other measures of socioeconomic status that districts and charters have used are worth paying close attention to. Some districts, such as Chicago Public Schools, look at census data for neighborhoods, measuring factors such as educational attainment, household income, percentage of owner-occupied homes, percentage of single-parent homes, and percentage of households where a language besides English is spoken. A student’s neighborhood then serves as a proxy for measuring her socioeconomic status. Other districts and charters—such as District of Columbia Public Schools in Washington, D.C.; Guilford County Public School District in North Carolina; and Community Roots Charter School in New York—look at students’ eligibility for other public assistance programs including homeless or migrant programs, foster care, TANF and SNAP, public housing, and Head Start. And several interdistrict transfer, magnet, and charter school programs in areas with high levels of segregation among school districts use a student’s home district (suburban versus urban) as a proxy for socioeconomic status.

Some programs also look at student achievement when considering transfers, seeking to create a mix of student achievement levels within a school, or to give students in lower-achieving schools chances to move to higher-achieving schools. While not technically a measure of socioeconomic status, we have included these achievement-based measures in our inventory, since they target one of the key levers through which socioeconomic integration promotes student achievement—by encouraging positive peer effects when students from different socioeconomic backgrounds and different achievement levels learn side by side.

List of School Districts and Charter Schools with Integration Policies

*Plurality = largest group less than 50 percent of student body. Majority = largest group 50–69 percent of student body. Supermajority = largest group at least 70 percent of student body.

Click here for additional data and information on sources.

Conclusion

Public education serves a dual purpose: to academically prepare our children with the knowledge and skills to contribute to the workforce, and to provide children with the opportunity to develop socially and emotionally in ways that contribute to social cohesion. Diversity of both income and race is essential in order for public education to fulfill either of these goals. Segregation impedes the ability of children to prepare for an increasingly diverse workforce; to function tolerantly and enthusiastically in a globalizing society; to lead, follow, and communicate with a wide variety of consumers, colleagues, and friends. The democratic principles of this nation are impossible to reach without universal access to a diverse, high quality, and engaging education. More concretely, we know that integrated schools boost individual student achievement, as well as attract and retain stronger teachers.62 School integration—more than increased funding, leadership changes, and stringent teacher evaluations—is the most effective known educational innovation.

The list presented in this report represents districts and charters that maintain policies that have the potential to maximize academic achievement and social competency among their students. Far from a “one-size-fits-all” prescription, our research shows that the approaches schools take toward integration—and their results—can vary according to the strength of the program design, the rigor of socioeconomic measurements, and the preexisting demographics of the district.

As more researchers begin to recognize the necessity of school integration, we will likely discover more information about which types of integration methods pair best with districts that present different demographic profiles. And we still require more information before deciding which of the districts on our list should be considered success stories: in many cases, the districts’ efforts are only the beginning of what is needed to foster integration. Many of the districts on our list are continuing to tweak their own plans in order to achieve their desired results, and thus their current levels of socioeconomic integration may not fit with their ideal goal.

Moving forward, we need more research to address remaining questions: Which districts are successful, and in what ways do their sizes, population densities, and levels of homogeneity influence their methods of integration? Will the design of one plan have similarly positive results in a district with a different population? How have districts struggled to construct their plans, and what were the sources of their obstacles?

The data we have so far is hopeful. Some districts with longstanding programs, such as Cambridge Public School District with its controlled choice plan, have seen steadily rising scores on state and national tests, as well as elevated high school graduation rates.63 Cambridge’s schools also maintained their racial balance even after the district transitioned from a race-based to a class-based integration plan. These results align with the findings of numerous studies that decry policies that sustain concentrated poverty in schools and make a case for economically mixed spaces.64

At the same time, advocates and practitioners should be careful to shape the definition of “success” into one that encourages true equity, rather than one that simply accepts a single step of progress as the completion of a goal. We know, for example, that integrated schoolhouses do not guarantee diverse classrooms.65 Districts taking important steps to ensure that their school population reflects the diversity of the community must also combat the problems of racialized tracking, inequity in school discipline rates and practices, and financial barriers to extracurricular participation. The degree to which socioeconomic school integration encourages the integration of classrooms and academic programs remains unclear, and represents an opportunity for further research.

Integration is a social justice imperative, carrying with it a long history of experimentation. Post Brown v. Board of Education, the legal landscape for school integration has transitioned from active judicial intervention and oversight to limitations on the use of race as an assignment factor. Politically, efforts to integrate schools—and thus maximize fairness—have triumphed over massive resistance, anti-busing protests, and school board battles. Socioeconomic school integration is the next step in a storied history of demanding justice for all children, of seeking to fulfill the American promise that education can be a great equalizer in a society that remains highly stratified. To this end, we hope that this report encourages districts to build on their current efforts to diversify their schools, and to continue to establish policies that maintain the levels of diversity once they reach the ideal balance. Now is the time to capitalize on the movement’s momentum.

EDITOR’S NOTE: As of October 2016, TCF has identified a total of one hundred districts and charter networks across the country that now use socioeconomic status as a factor in student assignment.

Notes

-

- 1. Halley Potter, “What Can We Do about Segregation in D.C. Schools?” The Century Foundation, March 18, 2014,

http://www.tcf.org/work/education/detail/controlled-choice-balances-schools

-

- .

2. Chana Joffe and Ira Glass, “563: The Problem We All Live With—Part Two,” This American Life, podcast transcript, August 7, 2015, http://www.thisamericanlife.org/radio-archives/episode/563/transcript.

3. Cara Fitzpatrick, Lisa Gartner, and Michael LaForgia, “Failure Factories,” Tampa Bay Times, August 14, 2015, http://www.tampabay.com/projects/2015/investigations/pinellas-failure-factories/5-schools-segregation/.

4. Amy Zimmer, “7 Elementary Schools Will Try to Boost Student Diversity in Pilot Program,” DNAinfo New York, November 20, 2015, http://www.dnainfo.com/new-york/20151120/fort-greene/7-brooklyn-manhattan-schools-win-fight-for-diversity-based-admissions.

5. Greg Toppo and Paul Overberg, “Diversity in the Classroom: Sides Square Off in Minnesota,” USA TODAY, November 25, 2014, http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2014/11/25/minnesota-school-race-diversity/18919391/.

6. Michael Magee, “The Mayors’ Charter Schools: Innovation Facilitates Socioeconomic Integration and High Performance,” EducationNext 14, no. 1 (Winter 2014), http://educationnext.org/the-mayors-charter-schools/.

7. Gary Orfield and Erica Frankenberg, Brown at 60: Great Progress, a Long Retreat and an Uncertain Future (Berkeley, Calif.: The Civil Rights Project, University of California-Berkeley, May 15, 2014), http://civilrightsproject.ucla.edu/research/k-12-education/integration-and-diversity/brown-at-60-great-progress-a-long-retreat-and-an-uncertain-future/Brown-at-60-051814.pdf.

8. Calculated from Erica Frankenberg, Genevieve Siegel-Hawley, and Jia Wang, Choice without Equity (Berkeley, Calif.: The Civil Rights Project, University of California-Berkeley, January 2010), 28, table 4; 43, table 11; and 38, table 8, http://civilrightsproject.ucla.edu/research/k-12-education/integration-and-diversity/choice-without-equity-2009-report/frankenberg-choices-without-equity-2010.pdf.

9. Paul Jargowsky, Architecture of Segregation: Civil Unrest, the Concentration of Poverty, and Public Policy (New York: The Century Foundation, August 7, 2015), http://www.tcf.org/work//detail/new-data-reveals-huge-increases-in-concentrated-poverty-since-2000.

10. Ann Owens, “Growing Economic Segregation among School Districts and Schools,” The Brown Center Chalkboard, Brookings Institution, September 10, 2015, http://www.brookings.edu/blogs/brown-center-chalkboard/posts/2015/09/10-growing-economic-segregation-schools-owens.

11. Orfield and Frankenberg, Brown at 60.

12. Ibid., 16.

13. Emma García and Elaine Weiss, Segregation and Peers’ Characteristics in the 2010–2011 Kindergarten Class (Washington, D.C.: Economic Policy Institute and the Broader, Bolder Approach to Education, June 11, 2014), fig. C, http://www.epi.org/publication/segregation-and-peers-characteristics/.

14. Jargowsky, Architecture of Segregation.

15. Philip Tegeler, Roslyn Arlin Mickelson, and Martha Bottia, “What We Know about School Integration, College Attendance, and the Reduction of Poverty,” National Coalition on School Diversity, Issue Brief no. 4, October 2010, updated March 2011, http://www.school-diversity.org/pdf/DiversityResearchBriefNo4.pdf; Susan Eaton, “How the Racial and Socioeconomic Composition of Schools and Classrooms Contributes to Literacy, Behavioral Climate, Instructional Organization and High School Graduation Rates,” National Coalition on School Diversity, Issue Brief no 2, October 2010, updated March, 2011, http://www.school-diversity.org/pdf/DiversityResearchBriefNo2.pdf; and Susan Eaton, “School Racial and Economic Composition and Math and Science Achievement,” National Coalition on School Diversity, Issue Brief no. 1, October 2010, updated March 2011, http://www.school-diversity.org/pdf/DiversityResearchBriefNo1.pdf.

16. Roslyn Arlin Mickelson and Martha Bottia, “Integrated Education and Mathematics Outcomes: A Synthesis of Social Science Research,” North Carolina Law Review 87 (2010): 1043.

17. Anthony Lising Antonio, et al., “Effects of Racial Diversity on Complex Thinking in College Students,” Psychological Science 15 (2004): 507–10; Brief of 553 Social Scientists as Amici Curiae in Support of Respondents, Parents Involved v. Seattle School District, No. 05-908, and Meredith v. Jefferson County, No. 05-915 (2006); Patricia Marin, “The Educational Possibility of Multi-Racial/Multi-Ethnic College Classrooms,” in Does Diversity Make a Difference? Three Research Studies on Diversity in College Classrooms, ed. American Council on Education & American Association of University Professors (Washington, D.C.: ACE & AAUP, 2000): 61–68, http://www.aaup.org/NR/rdonlyres/97003B7B-055F-4318-B14A-5336321FB742/0/DIVREP.PDF; Rebecca Bigler and L.S. Liben, “A Developmental Intergroup Theory of Social Stereotypes and Prejudices,” Advances in Child Development and Behavior 34 (2006): 67; Thomas F. Pettigrew and Linda R. Tropp, “A Meta-Analytic Test of Intergroup Contact Theory,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 90, no. 5 (2006): 751–83; Kristie J. R. Phillips, Robert J. Rodosky, Marco A. Muñoz, and Elisabeth S. Larsen, “Integrated Schools, Integrated Futures? A Case Study of School Desegregation in Jefferson County, Kentucky,” in From the Courtroom to the Classroom: The Shifting Landscape of School Desegregation, ed. Claire E. Smrekar and Ellen B. Goldring (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Education Press, 2009), pp. 239–70; and Elizabeth Stearns, “Long-Term Correlates of High School Racial Composition: Perpetuation Theory Reexamined,” Teachers College Record 112 (2010): 1654–78.

18. See, e.g., Richard D. Kahlenberg, All Together Now: Creating Middle-Class Schools through Public School Choice (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 2001); Divided We Fail: Coming Together Through Public School Choice (New York: Century Press, 2002); Richard D. Kahlenberg, Rescuing Brown v. Board of Education (New York: The Century Foundation, 2007), https://production-tcf.imgix.net/assets/downloads/tcf-districtprofiles.pdf; Richard D. Kahlenberg, Turnaround Schools That Work: Moving Beyond Separate but Equal (New York: The Century Foundation, 2009), https://production-tcf.imgix.net/assets/downloads/tcf-turnaround.pdf; The Future of School Integration, ed. Richard D. Kahlenberg (New York: The Century Foundation, 2012), http://www.tcf.org/bookstore/detail/the-future-of-school-integration; Jeanne L. Reid and Sharon Lynn Kagan, A Better Start: Why Classroom Diversity Matters in Early Education (Washington, D.C., and New York: The Century Foundation and the Poverty & Race Research Action Council, April 2015), http://www.tcf.org/bookstore/detail/a-better-start; and Halley Potter, Charters without Borders: Using Inter-district Charter Schools as a Tool for Regional School Integration (New York: The Century Foundation, 2015), http://www.tcf.org/bookstore/detail/charters-without-borders.

19. James S. Coleman, et al., Equality of Educational Opportunity (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Office of Education/National Center for Education Statistics), 325, http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED012275.

20. Richard D. Kahlenberg, “From All Walks of Life: New Hope for School Integration,” American Educator (Winter 2012–13), 2–40, http://www.aft.org/sites/default/files/periodicals/Kahlenberg.pdf.

21. Carl Chancellor and Richard D. Kahlenberg, “The New Segregation,” Washington Monthly, November/December 2014, http://www.washingtonmonthly.com/magazine/novemberdecember_2014/features/the_new_segregation052709.php?page=all.

22. Sean F. Reardon, “The Widening Income Achievement Gap,” Educational Leadership 70, no. 8 (May 2013): 10–16, http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational-leadership/may13/vol70/num08/The-Widening-Income-Achievement-Gap.aspx.

23. Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District #1; and U.S. Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division, and U.S. Department of Education, Office for Civil Rights, “Guidance on the Voluntary Use of Race to Achieve Diversity and Avoid Racial Isolation in Elementary and Secondary Schools,” December 2, 2011, http://www2.ed.gov/ocr/docs/guidance-ese-201111.pdf.

24. Duncan Chaplin, “Estimating the Impact of Economic Integration of Schools on Racial Integration,” in Divided We Fail: Coming Together Through Public School Choice (New York: Century Press, 2002), 87–113. It should be noted, however, that socioeconomic integration does not guarantee racial integration. See Sean F. Reardon, John T. Yun, and Michal Kurlaender, “Implications of Income-Based School Assignment Policies for Racial School Segregation,” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 28, no. 1 (Spring 2006): 49–75; and Sean F. Reardon and Lori Rhodes, “The Effects of Socioeconomic School Integration Policies on Racial School Desegregation,” in Integrating Schools in a Changing Society: New Policies and Legal Options for a Multiracial Generation, eds. Erica Frankenberg and Elizabeth Debray (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011), 187–207.

25. The goal of this report is to provide a tool that will help policymakers, education leaders, researchers, and advocates understand the broad landscape of socioeconomic integration strategies currently in use—not to provide legal guidance about the adoption of particular strategies by particular districts or charters. We have summarized integration plans in lay terms. For example, we sometimes use phrases such as “admissions preference” or “increased weight” interchangeably, when they may have particular legal meanings depending on the context.

26. Brandt Williams, “Suit Alleges Policies Promote Twin Cities School Segregation,” MPR News, November 5, 2015, http://www.mprnews.org/story/2015/11/05/school-segregation-lawsuit; Associated Press, “Judge to Weigh Desegregation Options for Cleveland Schools,” Jackson Free Press, May 19, 2015, http://www.jacksonfreepress.com/news/2015/may/19/judge-weigh-desegregation-options-cleveland-school/; and Denisa R. Superville, “New Settlement Reached in Hartford, Conn., Desegregation Case,” Education Week, February 27, 2015, http://blogs.edweek.org/edweek/District_Dossier/2015/02/new_settlement_reached_in_hart.html.

27. Amy Stuart Wells, Bianca J. Baldridge, Jacquelyn Duran, Courtney Grzesikowski, Richard Lofton, Allison Roda, Miya Warner, and Terrenda White, Boundary Crossing for Diversity, Equity and Achievement: Inter-district School Desegregation and Educational Opportunity (Cambridge, Mass.: Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race and Justice, Harvard Law School, November 2009), 1, citing Charles T. Clotfelter, After Brown: The Rise and Retreat of School Desegregation (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2004).

28. For more information on inter-district integration plans, see Halley Potter, Charters without Borders: Using Inter-district Charter Schools as a Tool for Regional School Integration (New York: The Century Foundation, 2015), http://www.tcf.org/bookstore/detail/charters-without-borders; and Kara S. Finnigan and Jennifer Jellison Holme, Regional Educational Equity Policies: Learning from Inter-district Integration Programs, Research Brief No. 9, National Coalition on School Diversity, September 2015, http://school-diversity.org/pdf/DiversityResearchBriefNo9.pdf.

29. We considered rezoning efforts to be sufficiently recent to affect current enrollment as long as we could not find evidence that they had been reversed by more recent rezoning decisions without socioeconomic considerations.

30. The Century Foundation’s previous lists of socioeconomic integration policies may be found in the following: Richard D. Kahlenberg, Rescuing Brown v. Board of Education (New York: The Century Foundation, 2007), 3–4, https://production-tcf.imgix.net/assets/downloads/tcf-districtprofiles.pdf; Richard D. Kahlenberg, Turnaround Schools That Work: Moving Beyond Separate but Equal (New York: The Century Foundation, 2009), Appendix, 20–21, https://production-tcf.imgix.net/assets/downloads/tcf-turnaround.pdf; and The Future of School Integration, ed. Richard D. Kahlenberg (New York: The Century Foundation, 2012), Appendix, 309–11, http://www.tcf.org/bookstore/detail/the-future-of-school-integration.

31. Nikole Hannah-Jones, “Lack of Order: The Erosion of a Once Great Force for Integration,” ProPublica, May 1, 2014, http://www.propublica.org/article/lack-of-order-the-erosion-of-a-once-great-force-for-integration.

32. Rachel Cohen, “School Choice and the Chaotic State of Racial Desegregation,” The American Prospect, September 15, 2015, http://prospect.org/article/school-choice-and-chaotic-state-racial-desegregation.

33. Erica Frankenberg, “Assessing the Status of School Desegregation Sixty Years after Brown,” Michigan State Law Review 677 (2014): 677–709.

34. U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Digest of Education Statistics 2014, March 2015, table 203.10, https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d14/tables/dt14_203.10.asp?current=yes.

35. See Sheneka M. Williams, “The Politics of Maintaining Balanced Schools: An Examination of Three Districts,” in The Future of School Integration, 256–82.

36. Justin Mayo, “6 Seattle Schools Have Become Whiter as New Assignment Plan Changes Racial Balance,” Seattle Times, August 21, 2012, http://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/education/6-seattle-schools-have-become-whiter-as-new-assignment-plan-changes-racial-balance/; and John Higgins, “Seattle School Board Oks Boundary Plan,” Seattle Times, November 21, 2013, http://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/education/seattle-school-board-oks-boundary-plan/.

37. U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, “Racial/Ethnic Enrollment in Public Schools,” The Condition of Education 2015, May 2015, http://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_cge.asp.

38. Richard D. Kahlenberg and Halley Potter, A Smarter Charter: Finding What Works for Charter Schools and Public Education (New York: Teachers College Press, 2014), 122; Madeleine F. Green, Minorities on Campus: A Handbook for Enhancing Diversity (Washington, D.C.: American Council on Education, 1989), 116; Jacinta S. Ma and Michal Kurlaender, “The Future of Race-Conscious Policies in K–12 Public Schools: Support from Recent Legal Opinions and Social Science Research,” in School Resegregation: Must the South Turn Back? ed. John Charles Boger and Gary Orfield (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005), 249; John B. McConahay, “Reducing racial Prejudice in Desegregated Schools,” in Effective School Desegregation: Equity, Quality, and Feasibility, ed. Willis D. Hawley (Beverly Hills, Calif.: Sage, 1981), 39; and Kevin G. Welner, “K–12 Race-Conscious Student Assignment Policies: Law, Social Science, and Diversity,” Review of Educational Research 76, no. 3 (2006): 349–82.

39. National Center for Education Statistics, Digest of Education Statistics 2014 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Education, 2014), Table 204.10, https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d14/tables/dt14_204.10.asp?current=yes.

40. Richard D. Kahlenberg, Rescuing Brown v. Board of Education (New York: The Century Foundation, 2007), 14–15, https://production-tcf.imgix.net/assets/downloads/tcf-districtprofiles.pdf.

41. Authors’ calculations based on National Center for Education Statistics, The Condition of Education 2009 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Education, 2009), 214–15, Table A-32-1, http://nces.ed.gov/pubs2009/2009081.pdf.

42. Greg Toppo and Paul Overberg, “Diversity in the Classroom: Sides Square Off in Minnesota,” USA TODAY, November 25, 2014, http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2014/11/25/minnesota-school-race-diversity/18919391/.

43. For past and current boundaries, see Institute on Race and Poverty, “Eden Prairie Schools Demographics and Attendance Boundaries,” http://www1.law.umn.edu/uploads/b5/d5/b5d5a92e04a7bc04854aeebf6a36a89f/40b-Eden_Prairie_school_trends_and_boundaries.pdf (accessed November 24, 2015); and Eden Prairie Schools, “School Boundaries,” http://www.edenpr.org/Page/1410 (accessed November 24, 2015).

44. Data from Institute on Race and Poverty, “Edent Prairie Schools Demographics and Attendance Boundaries”; and Minnesota Report Card, 2015 data, http://rc.education.state.mn.us/#mySchool/p–1.

45. McKinney Independent School District, “McKinney ISD 2014 High School Rezoning—FAQs,” Press Release, October 2013, http://www.mckinneyonline.com/October-2013/McKinney-ISD-2014-High-School-Rezoning-FAQs/index.php?cparticle=1&siarticle=0#artanc.

46. Priscilla Wohlstetter, Joanna Smith, and Caitlin C.Farrell, Choices and Challenges: Charter School Performance in Perspective (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Education Press, 2013), 126.

47. Charles Vert Willie, Ralph Edwards, and Michael J. Alves, Student Diversity, Choice and School Improvement (Westport, Conn.: Bergin and Garvey, 2002).

48. Champaign Unit 4 School District, “Update on Kindergarten Assignment Process,” April 24, 2012, http://www.champaignschools.org/news-room/article/3448.

49. Christine H. Rossell, “Magnet Schools: No Longer Famous, but Still Intact,” EducationNext 5, no. 2 (Spring 2005), http://educationnext.org/magnetschools/.

50. Robert Bifulco, Casey D. Cobb, and Courtney Bell, “Can Interdistrict Choice Boost Student Achievement? The Case of Connecticut’s Interdistrict Magnet School Program,” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 31, no. 4 (2009): 323–345; and Genevieve Siegel-Hawley and Erica Frankenberg, “Magnet School Student Outcomes: What the Research Says,” The National Coalition on School Diversity, Issue Brief no. 6, October 2011, http://www.school-diversity.org/pdf/DiversityResearchBriefNo6.pdf.

51. Julian Betts, Sami Kitmitto, Jesse Levin, Johannes Bos, and Marian Eaton, What Happens When Schools Become Magnet Schools? A Longitudinal Study of Diversity and Achievement, American Institutes for Research, May 2015, http://www.air.org/sites/default/files/downloads/report/Magnet-Schools-Diversity-and-Achievement-May-2015-rev.pdf.

52. Kahlenberg and Potter, A Smarter Charter.

53. See Halley Potter, Charters without Borders: Using Inter-district Charter Schools as a Tool for Regional School Integration (New York: The Century Foundation, 2015), http://www.tcf.org/bookstore/detail/charters-without-borders.

54. One of the authors (Halley Potter) is an adviser for the National Coalition of Diverse Charter Schools. See http://www.diversecharters.org/.

55. Jennifer Jellison Holme and Amy Stuart Wells, “School Choice beyond District Borders: Lessons for the Reauthorization of NCLB from Interdistrict Desegregation and Open Enrollment Plans,” in Improving on No Child Left Behind: Getting Education Reform Back on Track, ed. Richard D. Kahlenberg (New York: The Century Foundation Press, 2008), 156.

56. Kristie J. R. Phillips, Charles Hausman, and Elisabeth S. Larsen, “Students Who Choose and the Schools They Leave: Examining Participation in Intradistrict Transfers,” The Sociological Quarterly 53, no. 2 (2012): 264–94.

57. U.S. Department of Agriculture, “National School Lunch Program,” Fact Sheet, September 2013, http://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/NSLPFactSheet.pdf.