This piece was originally published by Next100, a startup think tank powered by The Century Foundation and created for—and by—the next generation of policy leaders.

Una versión de este artículo está disponible también en español aquí.

How do we get the COVID-19 pandemic under control so we can mitigate its harm and return to some sort of normalcy? Everyone in the federal government is ruminating on this question as they work to implement the CARES Act (the third COVID-19 emergency relief package), and consider what a “Phase 4” package should include.

Now imagine that you are dealing with this crisis while working in a minimum wage job without access to health insurance, losing your job because it’s not considered essential and it’s not something you can do from home, and not being able to tap into unemployment insurance. Or imagine that you continue working in your service sector or medical care job because you are an essential employee, you get sick and your family members do too, you lose your job because you can’t work, and don’t have access to unemployment insurance, all while being the primary provider for your family. Through it all, you don’t know where to turn, you are scared of a federal government that has threatened to detain and deport you, and you know that while the government passed a relief package to help people, none of that help has been extended to you or your family.

As community spread of the virus takes its toll, it is devastating working class neighborhoods. In New York City, neighborhoods with high numbers of Black and Brown residents have been hardest hit, including the immigrant enclaves of Central Queens. When data is disaggregated by race and ethnicity, it clearly shows that COVID-19 is having a disparate impact on Black and Latinx communities, not just in New York City, but across several states, including Louisiana, Michigan, North Carolina, and Illinois.

Unfortunately, it appears that mitigating the impact of this pandemic on the undocumented and mixed-status families who are especially vulnerable and facing the realities of exclusion is not of any special importance for our legislators. They need to adjust their priorities, and immediately: because these families deserve relief as much as everyone else, and because our nation’s well-being—medically as well as economically—is deeply dependent on theirs.

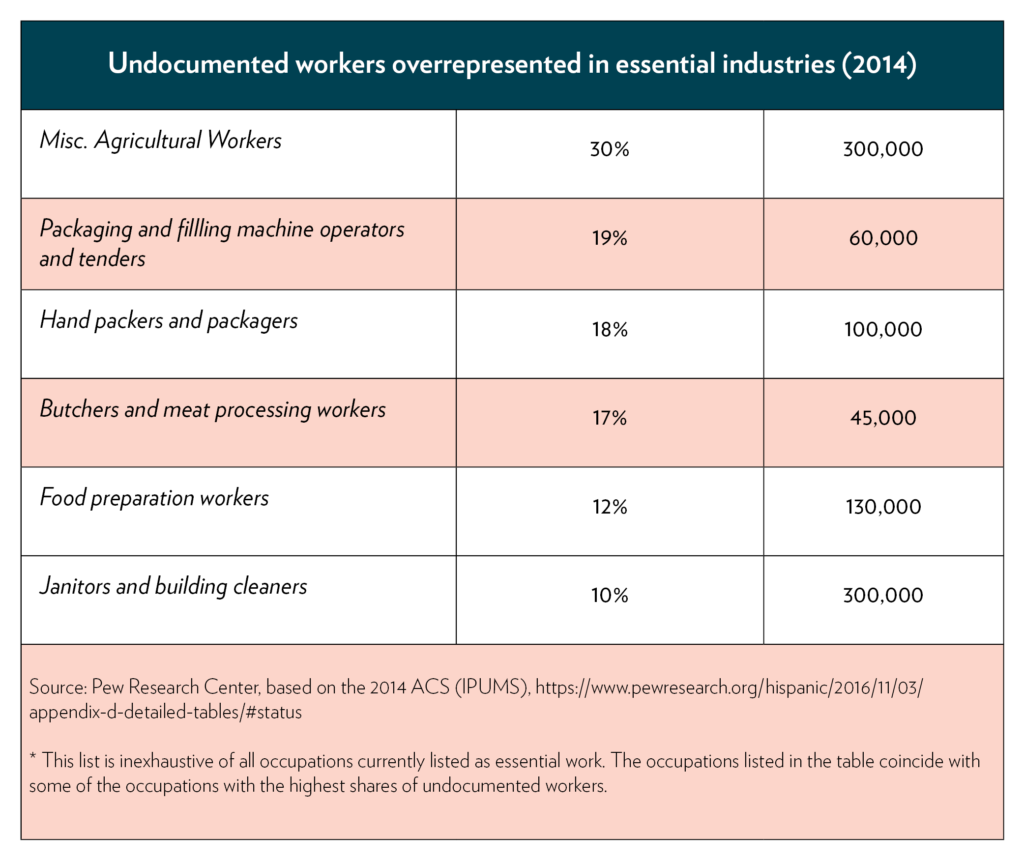

There are an estimated 11 million undocumented immigrants in this country. They make up about 5 percent of the workforce—one in twenty workers—and they are disproportionately represented in work that the government considers essential, including occupations in agriculture, food preparation, and food processing. Truly being concerned for the public health of the country means being concerned for these families too.

Recommendations for Expanding Relief to Undocumented Individuals (and Their Families) during the COVID-19 Pandemic

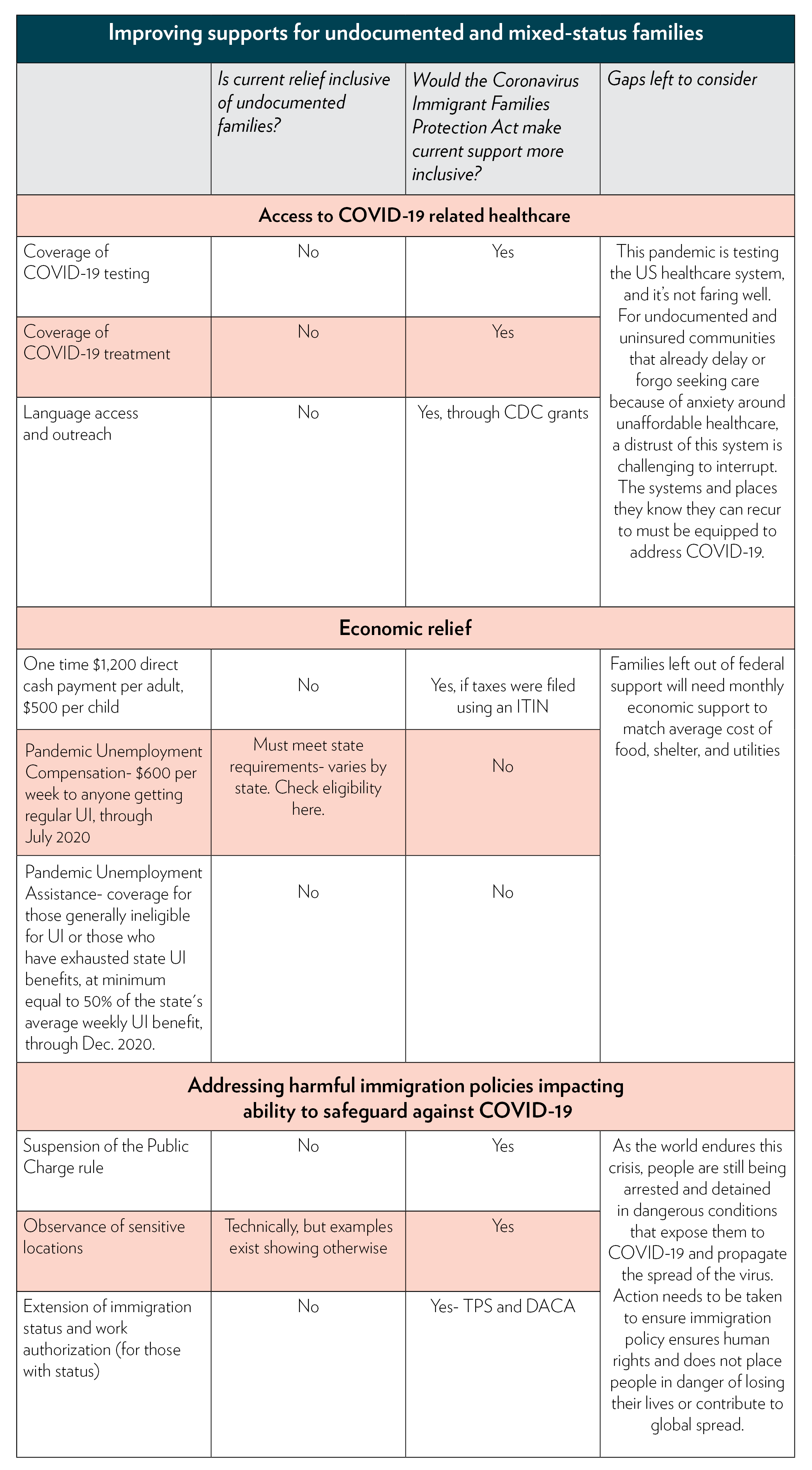

We are all concerned about how we will fare given the uncertainty surrounding the current moment; some people, however, face more precarity during this crisis than others. Some of the gaps that existed in caring for subsets of the population that are especially vulnerable to the pandemic were addressed in the CARES Act, such as unemployment assistance to help working families deal with economic hardship and increased medical funding to test for and treat the virus. Unfortunately, while the third emergency package promoted by House Speaker Pelosi was inclusive of undocumented and mixed-status families, those provisions did not make it into the CARES Act. In the end, for undocumented and mixed-status families in particular, very little was done.

Many policymakers know these exclusions are unacceptable, as evidenced by the introduction of the Coronavirus Immigrant Families Protection Act (CIFPA) on April 3rd, 2020. The bill was introduced in the House of Representatives by Representatives Raúl M. Grijalva (D-AZ), Judy Chu (D-CA), and Lou Correa (D-CA); and by Senators Mazie Hirono (D-HI) and Kamala Harris (D-CA) in the Senate. The bill calls for important measures addressing the exclusion of many immigrant families by the CARES Act, including: increasing access to COVID-19-related care for everyone by appropriating $100 million to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) for grants to improve language access and public outreach around COVID-19 in immigrant communities; expanding Medicaid coverage for COVID-19-related services, including testing, treatment, and vaccines to everyone, regardless of immigration status; allowing immigrants to access relief funds with an Individual Taxpayer Identification Number (ITIN); and modifying current immigration policies that deter immigrants from seeking health care, including suspending the implementation of the public charge rule and suspending immigration enforcement actions in and en-route to sensitive locations throughout the COVID-19 emergency and for sixty days after. The Federal Immigrant Release for Safety and Security Together (FIRST) Act was introduced in Congress by Senator Cory Booker (D-NJ) and Representative Pramila Jayapal (D-WA) on April 13, 2020. The bill calls for a release of certain individuals from detention centers, a review of additional immigration files to determine if additional individuals not covered under the provided definitions should continue being detained, a limitation on interior enforcement, access to hygienic products as well as telephone and video communications, and a process for redetention of individuals after the national emergency related to COVID-19 has ended.

The passage of this legislation would be an important step forward in truly prioritizing our collective well-being. Here’s why each measure is critical, and some additional steps that should be taken to support immigrant communities.

The Need to Increase Access to COVID-19-Related Care for Everyone, Regardless of Immigration Status

Because most undocumented immigrants need to keep working during the pandemic—and are likely to continue working, given the type of work they do—it is likely that many of them will come in contact with the virus. And yet to date, many immigrants are unable to access testing and treatment—despite the impact that the virus will have on them and their communities.

Medicaid Coverage of COVID-19 Treatment

Currently, only private insurance must cover the cost of treatment for COVID-19. However, passage of the CIFPA would ensure that Medicaid does the same, by classifying COVID-19 as an emergency medical condition. This would mean that uninsured individuals, including undocumented immigrants—45 percent of whom are uninsured—would have access to emergency Medicaid to help cover the cost of testing, evaluation, and treatment for coronavirus. Access to health insurance at this moment can be a difference between life and death, and hospitals need to know that they will be reimbursed for the care they provide, to decrease their likelihood of turning people away.

If the federal government fails to take the lead in passing the CIFPA, states can take action by following New York’s lead, where the state health department’s guidance ensures that undocumented New York residents are covered for COVID-19-related care by emergency Medicaid. Governors should not hesitate in demonstrating they care for the public health of their state by issuing updated Medicaid guidance that enables anyone, regardless of immigration status, to be eligible for COVID-19 testing and treatment.

CDC Grants to Improve Language Access and Public Outreach

Adequately responding to the pandemic in the United States requires a structured government response that includes everyone being sufficiently informed of what measures they can take to protect themselves and the people with whom they come in contact. This is a huge undertaking, given the amount of essential, and rapidly evolving, knowledge about COVID-19 and the vast diversity of the United States. Targeting funds to the CDC to ensure adequate and quick public outreach in multiple languages and formats will ensure English language proficiency, access to technology and the internet, or geography do not create barriers to access of information. The Coronavirus Immigrant Families Protections Act would ensure that COVID-19-related materials are translated into twelve additional languages, as outlined in FEMA’s language access plan: these include Arabic, Chinese, French, Haitian, Hindi, Japanese, Korean, Russian, Spanish, Tagalog, Urdu, and Vietnamese. Resources in these translations will be made available to the public within a week after being published in English. The act also calls for establishing an informational hotline available to the public in all of the languages outlined in the FEMA plan.

The Need to Increase Access to COVID-19-Related Economic Relief to Everyone, Regardless of Immigration Status

Undocumented individuals pour generously into the United States economy, including by paying taxes to support out social safety net. They contribute to Social Security and Medicare trust funds, helping ensure our vulnerable elderly population is taken care of, even as they are themselves excluded from the majority of federal benefit programs. Many undocumented immigrants, as well as other “non-resident and resident aliens,” file personal income taxes with an individual taxpayer identification number (ITIN). According to IRS data, 4.4 million ITIN filers paid $23.6 billion in total taxes in 2015, and over $5.5 billion in payroll and Medicare taxes alone. And yet the CARES Act excludes undocumented individuals from any of the economic support being provided to others, including the following:

- Undocumented immigrants are not eligible for unemployment insurance (UI), for which the CARES Act provides a generous (and critical) expansion.

- They are not eligible for the new Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) program created by the CARES Act, meant to fill some of the gaps in unemployment insurance by supporting self-employed workers.

- They are not eligible for the $1,200 direct cash payment to individuals, another new program. These exclusions from direct cash payments apply even if an immigrant paid their taxes using an ITIN. Moreover, these exclusions apply to U.S. citizens who are family members (including children) and/or married to individuals using ITINs. This could affect approximately 16.7 million individuals living in mixed-status households, including prohibiting eight million U.S. citizens, 5.9 million who are children, from accessing their direct cash payments.

It is unacceptable that Congress would allow the COVID-19 crisis to further aggravate social inequity and public health disparities by excluding any family from receiving the assistance they need to ensure they have safe and clean shelter and food to eat. The CIFPA addresses these dangerous flaws by ensuring that any adult who filed their taxes, whether with an ITIN or a social security number, will be included in the $1,200 direct cash payment. These individuals are taxpayers who contribute to and help uphold a safety net in the United States like any other taxpayer, and like everyone else, they should be supported at this unprecedented moment of crisis.

The Need to Delay or Modify Other Immigration Policies

The COVID-19 pandemic’s effects on the immigrant population have been dramatically worsened by the Trump administration’s harmful immigration policies. The following policies in the CIFPA won’t permanently solve those problems, but they will provide crucial relief from them during this crisis.

Suspension of the Public Charge Rule

U.S. Customs and Immigration Services (USCIS) has stated that any testing, treatment, or preventative care related to COVID-19 does not jeopardize anyone seeking to adjust their immigration status because it will not count as a public charge inadmissibility determination. That being said, it is important not to conflate the USCIS policy with increased accessibility or support for undocumented immigrants seeking testing and treatment for COVID-19. Undocumented immigrants were already ineligible for the benefits to which the public charge determination prohibits access. Furthermore, the chilling effect of the public charge rule, which went into effect at the end of February, has already caused many immigrants to pull out of the safety net programs they or their children were legally allowed to access. Therefore a USCIS announcement regarding public charge determinations is not enough to address the real fear undocumented immigrants may be facing when they seek care for COVID-19. If Congress actually cares to ensure everyone who needs medical care to address COVID-19 can do so, it should eliminate the confusion existing for many immigrant families by immediately suspending the public charge rule throughout the COVID-19 emergency.

Suspension of Immigration Enforcement at and en-route to Sensitive Locations, Including When Immigrants Are Seeking Health Care

People should also not be scared that they will be picked up by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) as they seek care. While guidance already exists around ICE respecting sensitive locations, this has not always been honored under the Trump administration. It is important that Congress get involved in increasing a sense of safety for undocumented immigrants during this pandemic. The CIFPA not only prohibits the secretary of homeland security from conducting enforcement action against individuals at established sensitive locations absent a judicial warrant, it also expands the definition of sensitive locations to include places providing emergency services, public assistance offices, and businesses providing essential services like grocery stores and pharmacies, among others.

Extension of Immigration Status and Employment Authorization

The CIFPA also calls on the secretary of homeland security to automatically extend the immigration status and work authorization of anyone whose immigration status expired within thirty days of the act’s enactment, is set to expire within a year of enactment, or ninety days after the national COVID-19 emergency is rescinded. The extensions granted would coincide with the amount of time for which the immigration status and work authorization was initially granted. This measure means that no additional immigrants, including those with Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) status or temporary protected status (TPS), would lose their status amidst the COVID-19 emergency, thereby losing their work permits and being at risk of deportation. Such an action recognizes the integral role of immigrants to the COVID-19 response, and it would allow the approximately 700,000 recipients of DACA and 411,000 foreign nationals with TPS a sense of security that they can continue to provide for their families and support their communities.

Minimize the Populations Being Held in Dangerous ICE Detention Centers

The secretary of homeland security has not stopped Immigrations and Customs Enforcement from continuing to arrest and detain undocumented immigrants, all while the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) maintains crowded and unhygienic conditions at detention centers that were costing lives prior to COVID-19 and are especially dangerous given this pandemic. Amidst this public health crisis, the actions of DHS are endangering our public well-being. Undocumented immigrants, just like everyone else, need to be able to seek care when they are unwell and maintain social distancing and the hygiene recommendations established by the Centers for Disease Control. No one’s life should be placed at risk because of their immigration status. The FIRST Act seeks to put the following measures in place to protect lives:

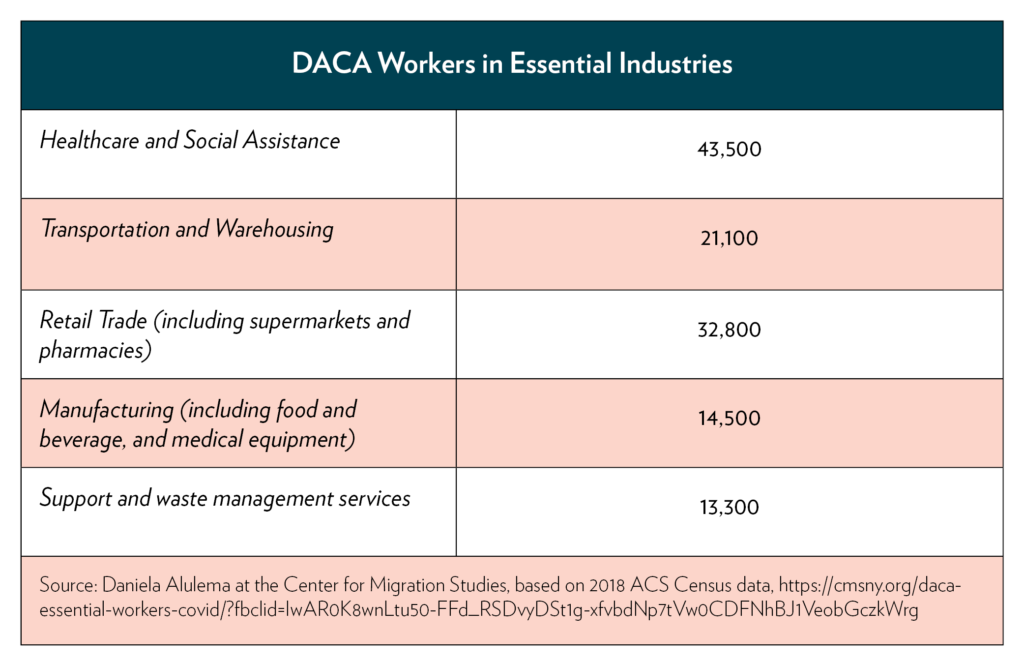

Delay the Decision on DACA

To further complicate things, the Supreme Court is expected to rule on what will happen with the DACA program and whether it will continue. This looming decision is weighing heavily on the well-being of DACA recipients, who comprise additional essential workers—including 43,500 working in health care and social assistance industries—who are putting their lives on the line to protect us. The Supreme Court should get out of the way of our national emergency response and DACA recipients’ ability to provide for their families by postponing their decision amidst this pandemic; and when they do rule, should allow the program to continue.

Legislation should also ensure the following:

Additional Funding for Community Health Centers and Community Health Workers

Community health centers (CHC) are important health care facilities that vulnerable populations should feel comfortable continuing to access, especially if the federal government does not advance on expanding eligibility for Medicaid to anyone seeking treatment for COVID-19. When undocumented immigrants seek affordable health care, they are generally directed to CHCs, which mainly focus on preventative and primary care. However, during this pandemic, CHCs are likely to face all the challenges that any hospital is currently seeing, including shortages of personal protective equipment for health care providers. They are also addressing additional challenges, including an increase in the provision of uncompensated care, primary care physician shortages, and decreased Medicaid funding; and short-term federal funding is slated to end in May 2020. As a first step, the CARES Act has provided $1.3 billion for CHCs for COVID-19 testing and treatment, as well as an increase of more than $2 billion for general services, to address the impending end of federal funding; but that is not enough. Congress must provide additional funding for CHCs to care for our most vulnerable populations.

Funding should also prioritize scaling up programs that have been successful in developing community health workers (CHWs), who serve as a bridge to ensure vulnerable populations have access to health and social services. CHWs are often recruited from the communities they work with, positioning them with access to hard-to-reach populations and helping ensure people are met with a deep sense of cultural understanding and trust. CHWs could help ensure that people who contract the virus connect with health providers virtually to receive the care they need at home and prevent reaching a critical condition. To address COVID-19, CHWs should be equipped with training on infection prevention and control, as well as the protective gear to keep themselves safe.

Addressing the Inability to Self-Quarantine

For individuals in undocumented and mixed-status families living in overcrowded or multiple-family homes, getting sick poses a threat to the rest of the household and may result in housing insecurity, especially when there is no space to self-quarantine within the home and others in the home have to keep working. Just as partnerships are being developed between private hotels and motels, state and local governments, and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to address the vulnerability of the homeless population to COVID-19, these partnerships should take into consideration overcrowded conditions in homes and the presence of essential workers in the household. Intake forms could request information on a patient’s living conditions and connect people with necessary services in case returning home is not the safest option.

Monthly Relief

Everyone who has had their income reduced as a result of COVID-19, regardless of immigration status, should have access to monthly relief throughout this crisis to cover the cost of food, shelter, and utilities, and that relief should take into account the average cost of those basic necessities. If the government can provide subsidies ensuring corporations are taken care of, it can also develop a system that ensures the well-being of its people.

The Ripple Effect of Exclusion

The impact of exclusions from protections and relief during this pandemic extends well beyond the estimated 11 million undocumented people and their families. It also impacts all frontline responders who interact with and care for anyone in the community regardless of their own immigration status, including, but not limited to, health care workers, educators, and advocates. CHCs, schools, and nonprofit organizations are tasked with being at the frontlines of addressing the needs of vulnerable populations, including undocumented and mixed-status immigrant families.

Nonprofit organizations serving undocumented communities have quickly set up funds to support their communities, and have compiled lists of the resources available. For instance, to support access to health care for undocumented immigrants, United We Dream compiled a list of CHC resources by state. Organizations like Hola Carolina in North Carolina are ensuring quality resources regarding COVID-19 are available in Spanish. However, these resources are not able to meet the demands generated by a government that continues playing the politics of exclusion and division, even as it addresses this crisis.

Schools and districts throughout the country have attempted to quickly shift to virtual learning in an effort to continue to provide routine education for students and minimize interruptions to learning. They are doing this across vast inequities in education, some of which may be exacerbated through the technological solutions being used. They are also responding to the needs of their students and families regarding access to resources to address economic hardship. When the government fails to include undocumented and mixed-status families, what are these institutions supposed to tell these families? They’ve scrambled to look through and find applicable resources, where they have capacity; many schools in vulnerable communities that lack social work teams and parent coordinators may struggle with such a task.

Further, geography plays a tremendous role when it comes to the amount of resources available. Advocates in states like New York and California, which have robust existing infrastructure that includes immigrant rights and civil rights organizations that have been fighting on behalf of immigrants, are better able to mobilize for resources and policy that is inclusive of their undocumented community. The programs comprising the safety net for undocumented immigrants in the United States are all doing what they can, many operating at capacity or over it, and without a federal government response, the additional strain of this crisis may prove unbearable. It is precisely in this moment that the federal government has an obligation and opportunity to demonstrate it can pull together to take care of us all.

Recognizing and Supporting the Leadership We Need

This country has always depended on the labor contributions of the undocumented community, and right now, we are especially dependent on them and their well-being for our livelihood. Adequately surmounting the challenges at hand demands a collective response that examines our values and recognizes everyone’s humanity and how interconnected our well-being is. Leaders need to understand that by creating vulnerable populations through exclusion, they are weakening the collective fabric of society through the additional strain on everyone. This is visibly, physically true at this moment due to the current pandemic; but it is always true. To protect our communities, we have no option but to see the humanity of everyone regardless of immigration status. I can’t be okay if I know my neighbor isn’t protected. For those of us with the privilege of moving through this moment with a continued sense of security, we have to leverage our voices to demand that the government includes everyone in relief and protections. If the federal government continues to fail at doing so, we will have to be the leaders by developing and contributing to the structures that will allow us to care for one another and provide real relief through this crisis. That leadership is already being seen throughout the country—Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey and Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot have ensured that undocumented and mixed-status families are included and eligible for COVID-19 disaster relief in their cities. California established an assistance fund to support families left out of federal relief package because of immigration status, and San Francisco educators are standing in solidarity with undocumented families by pledging a percentage of their stimulus checks to them.

Nonprofit organizations including the New York State Youth Leadership Council, the UndocuBlack Network, Revolutionizing Asian American Immigrant Stories on the East Coast, the Betancourt Macias Family Scholarship Foundation, ImmSchools, and a collaboration of immigrant rights organizations in Washington, amongst others, have created their own funds as well. They need as much support as possible, and you can help by making a monetary donation.

header photo: Melanie Cervantes with Dignidad Rebelde.

Tags: covid-19, immigration

Our Undocumented Community Needs Support in Addressing COVID-19

This piece was originally published by Next100, a startup think tank powered by The Century Foundation and created for—and by—the next generation of policy leaders.

Una versión de este artículo está disponible también en español aquí.

How do we get the COVID-19 pandemic under control so we can mitigate its harm and return to some sort of normalcy? Everyone in the federal government is ruminating on this question as they work to implement the CARES Act (the third COVID-19 emergency relief package), and consider what a “Phase 4” package should include.

Now imagine that you are dealing with this crisis while working in a minimum wage job without access to health insurance, losing your job because it’s not considered essential and it’s not something you can do from home, and not being able to tap into unemployment insurance. Or imagine that you continue working in your service sector or medical care job because you are an essential employee, you get sick and your family members do too, you lose your job because you can’t work, and don’t have access to unemployment insurance, all while being the primary provider for your family. Through it all, you don’t know where to turn, you are scared of a federal government that has threatened to detain and deport you, and you know that while the government passed a relief package to help people, none of that help has been extended to you or your family.

As community spread of the virus takes its toll, it is devastating working class neighborhoods. In New York City, neighborhoods with high numbers of Black and Brown residents have been hardest hit, including the immigrant enclaves of Central Queens. When data is disaggregated by race and ethnicity, it clearly shows that COVID-19 is having a disparate impact on Black and Latinx communities, not just in New York City, but across several states, including Louisiana, Michigan, North Carolina, and Illinois.

Unfortunately, it appears that mitigating the impact of this pandemic on the undocumented and mixed-status families who are especially vulnerable and facing the realities of exclusion is not of any special importance for our legislators. They need to adjust their priorities, and immediately: because these families deserve relief as much as everyone else, and because our nation’s well-being—medically as well as economically—is deeply dependent on theirs.

There are an estimated 11 million undocumented immigrants in this country. They make up about 5 percent of the workforce—one in twenty workers—and they are disproportionately represented in work that the government considers essential, including occupations in agriculture, food preparation, and food processing. Truly being concerned for the public health of the country means being concerned for these families too.

Recommendations for Expanding Relief to Undocumented Individuals (and Their Families) during the COVID-19 Pandemic

We are all concerned about how we will fare given the uncertainty surrounding the current moment; some people, however, face more precarity during this crisis than others. Some of the gaps that existed in caring for subsets of the population that are especially vulnerable to the pandemic were addressed in the CARES Act, such as unemployment assistance to help working families deal with economic hardship and increased medical funding to test for and treat the virus. Unfortunately, while the third emergency package promoted by House Speaker Pelosi was inclusive of undocumented and mixed-status families, those provisions did not make it into the CARES Act. In the end, for undocumented and mixed-status families in particular, very little was done.

Many policymakers know these exclusions are unacceptable, as evidenced by the introduction of the Coronavirus Immigrant Families Protection Act (CIFPA) on April 3rd, 2020. The bill was introduced in the House of Representatives by Representatives Raúl M. Grijalva (D-AZ), Judy Chu (D-CA), and Lou Correa (D-CA); and by Senators Mazie Hirono (D-HI) and Kamala Harris (D-CA) in the Senate. The bill calls for important measures addressing the exclusion of many immigrant families by the CARES Act, including: increasing access to COVID-19-related care for everyone by appropriating $100 million to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) for grants to improve language access and public outreach around COVID-19 in immigrant communities; expanding Medicaid coverage for COVID-19-related services, including testing, treatment, and vaccines to everyone, regardless of immigration status; allowing immigrants to access relief funds with an Individual Taxpayer Identification Number (ITIN); and modifying current immigration policies that deter immigrants from seeking health care, including suspending the implementation of the public charge rule and suspending immigration enforcement actions in and en-route to sensitive locations throughout the COVID-19 emergency and for sixty days after. The Federal Immigrant Release for Safety and Security Together (FIRST) Act was introduced in Congress by Senator Cory Booker (D-NJ) and Representative Pramila Jayapal (D-WA) on April 13, 2020. The bill calls for a release of certain individuals from detention centers, a review of additional immigration files to determine if additional individuals not covered under the provided definitions should continue being detained, a limitation on interior enforcement, access to hygienic products as well as telephone and video communications, and a process for redetention of individuals after the national emergency related to COVID-19 has ended.

The passage of this legislation would be an important step forward in truly prioritizing our collective well-being. Here’s why each measure is critical, and some additional steps that should be taken to support immigrant communities.

Sign up for updates.

The Need to Increase Access to COVID-19-Related Care for Everyone, Regardless of Immigration Status

Because most undocumented immigrants need to keep working during the pandemic—and are likely to continue working, given the type of work they do—it is likely that many of them will come in contact with the virus. And yet to date, many immigrants are unable to access testing and treatment—despite the impact that the virus will have on them and their communities.

Medicaid Coverage of COVID-19 Treatment

Currently, only private insurance must cover the cost of treatment for COVID-19. However, passage of the CIFPA would ensure that Medicaid does the same, by classifying COVID-19 as an emergency medical condition. This would mean that uninsured individuals, including undocumented immigrants—45 percent of whom are uninsured—would have access to emergency Medicaid to help cover the cost of testing, evaluation, and treatment for coronavirus. Access to health insurance at this moment can be a difference between life and death, and hospitals need to know that they will be reimbursed for the care they provide, to decrease their likelihood of turning people away.

If the federal government fails to take the lead in passing the CIFPA, states can take action by following New York’s lead, where the state health department’s guidance ensures that undocumented New York residents are covered for COVID-19-related care by emergency Medicaid. Governors should not hesitate in demonstrating they care for the public health of their state by issuing updated Medicaid guidance that enables anyone, regardless of immigration status, to be eligible for COVID-19 testing and treatment.

CDC Grants to Improve Language Access and Public Outreach

Adequately responding to the pandemic in the United States requires a structured government response that includes everyone being sufficiently informed of what measures they can take to protect themselves and the people with whom they come in contact. This is a huge undertaking, given the amount of essential, and rapidly evolving, knowledge about COVID-19 and the vast diversity of the United States. Targeting funds to the CDC to ensure adequate and quick public outreach in multiple languages and formats will ensure English language proficiency, access to technology and the internet, or geography do not create barriers to access of information. The Coronavirus Immigrant Families Protections Act would ensure that COVID-19-related materials are translated into twelve additional languages, as outlined in FEMA’s language access plan: these include Arabic, Chinese, French, Haitian, Hindi, Japanese, Korean, Russian, Spanish, Tagalog, Urdu, and Vietnamese. Resources in these translations will be made available to the public within a week after being published in English. The act also calls for establishing an informational hotline available to the public in all of the languages outlined in the FEMA plan.

The Need to Increase Access to COVID-19-Related Economic Relief to Everyone, Regardless of Immigration Status

Undocumented individuals pour generously into the United States economy, including by paying taxes to support out social safety net. They contribute to Social Security and Medicare trust funds, helping ensure our vulnerable elderly population is taken care of, even as they are themselves excluded from the majority of federal benefit programs. Many undocumented immigrants, as well as other “non-resident and resident aliens,” file personal income taxes with an individual taxpayer identification number (ITIN). According to IRS data, 4.4 million ITIN filers paid $23.6 billion in total taxes in 2015, and over $5.5 billion in payroll and Medicare taxes alone. And yet the CARES Act excludes undocumented individuals from any of the economic support being provided to others, including the following:

It is unacceptable that Congress would allow the COVID-19 crisis to further aggravate social inequity and public health disparities by excluding any family from receiving the assistance they need to ensure they have safe and clean shelter and food to eat. The CIFPA addresses these dangerous flaws by ensuring that any adult who filed their taxes, whether with an ITIN or a social security number, will be included in the $1,200 direct cash payment. These individuals are taxpayers who contribute to and help uphold a safety net in the United States like any other taxpayer, and like everyone else, they should be supported at this unprecedented moment of crisis.

The Need to Delay or Modify Other Immigration Policies

The COVID-19 pandemic’s effects on the immigrant population have been dramatically worsened by the Trump administration’s harmful immigration policies. The following policies in the CIFPA won’t permanently solve those problems, but they will provide crucial relief from them during this crisis.

Suspension of the Public Charge Rule

U.S. Customs and Immigration Services (USCIS) has stated that any testing, treatment, or preventative care related to COVID-19 does not jeopardize anyone seeking to adjust their immigration status because it will not count as a public charge inadmissibility determination. That being said, it is important not to conflate the USCIS policy with increased accessibility or support for undocumented immigrants seeking testing and treatment for COVID-19. Undocumented immigrants were already ineligible for the benefits to which the public charge determination prohibits access. Furthermore, the chilling effect of the public charge rule, which went into effect at the end of February, has already caused many immigrants to pull out of the safety net programs they or their children were legally allowed to access. Therefore a USCIS announcement regarding public charge determinations is not enough to address the real fear undocumented immigrants may be facing when they seek care for COVID-19. If Congress actually cares to ensure everyone who needs medical care to address COVID-19 can do so, it should eliminate the confusion existing for many immigrant families by immediately suspending the public charge rule throughout the COVID-19 emergency.

Suspension of Immigration Enforcement at and en-route to Sensitive Locations, Including When Immigrants Are Seeking Health Care

People should also not be scared that they will be picked up by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) as they seek care. While guidance already exists around ICE respecting sensitive locations, this has not always been honored under the Trump administration. It is important that Congress get involved in increasing a sense of safety for undocumented immigrants during this pandemic. The CIFPA not only prohibits the secretary of homeland security from conducting enforcement action against individuals at established sensitive locations absent a judicial warrant, it also expands the definition of sensitive locations to include places providing emergency services, public assistance offices, and businesses providing essential services like grocery stores and pharmacies, among others.

Extension of Immigration Status and Employment Authorization

The CIFPA also calls on the secretary of homeland security to automatically extend the immigration status and work authorization of anyone whose immigration status expired within thirty days of the act’s enactment, is set to expire within a year of enactment, or ninety days after the national COVID-19 emergency is rescinded. The extensions granted would coincide with the amount of time for which the immigration status and work authorization was initially granted. This measure means that no additional immigrants, including those with Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) status or temporary protected status (TPS), would lose their status amidst the COVID-19 emergency, thereby losing their work permits and being at risk of deportation. Such an action recognizes the integral role of immigrants to the COVID-19 response, and it would allow the approximately 700,000 recipients of DACA and 411,000 foreign nationals with TPS a sense of security that they can continue to provide for their families and support their communities.

Minimize the Populations Being Held in Dangerous ICE Detention Centers

The secretary of homeland security has not stopped Immigrations and Customs Enforcement from continuing to arrest and detain undocumented immigrants, all while the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) maintains crowded and unhygienic conditions at detention centers that were costing lives prior to COVID-19 and are especially dangerous given this pandemic. Amidst this public health crisis, the actions of DHS are endangering our public well-being. Undocumented immigrants, just like everyone else, need to be able to seek care when they are unwell and maintain social distancing and the hygiene recommendations established by the Centers for Disease Control. No one’s life should be placed at risk because of their immigration status. The FIRST Act seeks to put the following measures in place to protect lives:

Delay the Decision on DACA

To further complicate things, the Supreme Court is expected to rule on what will happen with the DACA program and whether it will continue. This looming decision is weighing heavily on the well-being of DACA recipients, who comprise additional essential workers—including 43,500 working in health care and social assistance industries—who are putting their lives on the line to protect us. The Supreme Court should get out of the way of our national emergency response and DACA recipients’ ability to provide for their families by postponing their decision amidst this pandemic; and when they do rule, should allow the program to continue.

Legislation should also ensure the following:

Additional Funding for Community Health Centers and Community Health Workers

Community health centers (CHC) are important health care facilities that vulnerable populations should feel comfortable continuing to access, especially if the federal government does not advance on expanding eligibility for Medicaid to anyone seeking treatment for COVID-19. When undocumented immigrants seek affordable health care, they are generally directed to CHCs, which mainly focus on preventative and primary care. However, during this pandemic, CHCs are likely to face all the challenges that any hospital is currently seeing, including shortages of personal protective equipment for health care providers. They are also addressing additional challenges, including an increase in the provision of uncompensated care, primary care physician shortages, and decreased Medicaid funding; and short-term federal funding is slated to end in May 2020. As a first step, the CARES Act has provided $1.3 billion for CHCs for COVID-19 testing and treatment, as well as an increase of more than $2 billion for general services, to address the impending end of federal funding; but that is not enough. Congress must provide additional funding for CHCs to care for our most vulnerable populations.

Funding should also prioritize scaling up programs that have been successful in developing community health workers (CHWs), who serve as a bridge to ensure vulnerable populations have access to health and social services. CHWs are often recruited from the communities they work with, positioning them with access to hard-to-reach populations and helping ensure people are met with a deep sense of cultural understanding and trust. CHWs could help ensure that people who contract the virus connect with health providers virtually to receive the care they need at home and prevent reaching a critical condition. To address COVID-19, CHWs should be equipped with training on infection prevention and control, as well as the protective gear to keep themselves safe.

Addressing the Inability to Self-Quarantine

For individuals in undocumented and mixed-status families living in overcrowded or multiple-family homes, getting sick poses a threat to the rest of the household and may result in housing insecurity, especially when there is no space to self-quarantine within the home and others in the home have to keep working. Just as partnerships are being developed between private hotels and motels, state and local governments, and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to address the vulnerability of the homeless population to COVID-19, these partnerships should take into consideration overcrowded conditions in homes and the presence of essential workers in the household. Intake forms could request information on a patient’s living conditions and connect people with necessary services in case returning home is not the safest option.

Monthly Relief

Everyone who has had their income reduced as a result of COVID-19, regardless of immigration status, should have access to monthly relief throughout this crisis to cover the cost of food, shelter, and utilities, and that relief should take into account the average cost of those basic necessities. If the government can provide subsidies ensuring corporations are taken care of, it can also develop a system that ensures the well-being of its people.

The Ripple Effect of Exclusion

The impact of exclusions from protections and relief during this pandemic extends well beyond the estimated 11 million undocumented people and their families. It also impacts all frontline responders who interact with and care for anyone in the community regardless of their own immigration status, including, but not limited to, health care workers, educators, and advocates. CHCs, schools, and nonprofit organizations are tasked with being at the frontlines of addressing the needs of vulnerable populations, including undocumented and mixed-status immigrant families.

Nonprofit organizations serving undocumented communities have quickly set up funds to support their communities, and have compiled lists of the resources available. For instance, to support access to health care for undocumented immigrants, United We Dream compiled a list of CHC resources by state. Organizations like Hola Carolina in North Carolina are ensuring quality resources regarding COVID-19 are available in Spanish. However, these resources are not able to meet the demands generated by a government that continues playing the politics of exclusion and division, even as it addresses this crisis.

Schools and districts throughout the country have attempted to quickly shift to virtual learning in an effort to continue to provide routine education for students and minimize interruptions to learning. They are doing this across vast inequities in education, some of which may be exacerbated through the technological solutions being used. They are also responding to the needs of their students and families regarding access to resources to address economic hardship. When the government fails to include undocumented and mixed-status families, what are these institutions supposed to tell these families? They’ve scrambled to look through and find applicable resources, where they have capacity; many schools in vulnerable communities that lack social work teams and parent coordinators may struggle with such a task.

Further, geography plays a tremendous role when it comes to the amount of resources available. Advocates in states like New York and California, which have robust existing infrastructure that includes immigrant rights and civil rights organizations that have been fighting on behalf of immigrants, are better able to mobilize for resources and policy that is inclusive of their undocumented community. The programs comprising the safety net for undocumented immigrants in the United States are all doing what they can, many operating at capacity or over it, and without a federal government response, the additional strain of this crisis may prove unbearable. It is precisely in this moment that the federal government has an obligation and opportunity to demonstrate it can pull together to take care of us all.

Recognizing and Supporting the Leadership We Need

This country has always depended on the labor contributions of the undocumented community, and right now, we are especially dependent on them and their well-being for our livelihood. Adequately surmounting the challenges at hand demands a collective response that examines our values and recognizes everyone’s humanity and how interconnected our well-being is. Leaders need to understand that by creating vulnerable populations through exclusion, they are weakening the collective fabric of society through the additional strain on everyone. This is visibly, physically true at this moment due to the current pandemic; but it is always true. To protect our communities, we have no option but to see the humanity of everyone regardless of immigration status. I can’t be okay if I know my neighbor isn’t protected. For those of us with the privilege of moving through this moment with a continued sense of security, we have to leverage our voices to demand that the government includes everyone in relief and protections. If the federal government continues to fail at doing so, we will have to be the leaders by developing and contributing to the structures that will allow us to care for one another and provide real relief through this crisis. That leadership is already being seen throughout the country—Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey and Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot have ensured that undocumented and mixed-status families are included and eligible for COVID-19 disaster relief in their cities. California established an assistance fund to support families left out of federal relief package because of immigration status, and San Francisco educators are standing in solidarity with undocumented families by pledging a percentage of their stimulus checks to them.

Nonprofit organizations including the New York State Youth Leadership Council, the UndocuBlack Network, Revolutionizing Asian American Immigrant Stories on the East Coast, the Betancourt Macias Family Scholarship Foundation, ImmSchools, and a collaboration of immigrant rights organizations in Washington, amongst others, have created their own funds as well. They need as much support as possible, and you can help by making a monetary donation.

header photo: Melanie Cervantes with Dignidad Rebelde.

Tags: covid-19, immigration