Changes are on the horizon for Americans with pre-existing conditions under a Trump presidency. While Trump said he had only “concepts of a plan,” J.D. Vance stated on Meet the Press that the best approach to covering people is to “not have a one-size-fits-all approach that puts a lot of people into the same insurance pools, into the same risk pools.”

This likely translates into trying, again, to repeal the Affordable Care Act (ACA) provisions that mainstream people with pre-existing conditions into private health insurance.

Many of us have pre-existing conditions. They are generally defined as having a known health condition (or history of it) that requires costly treatment, including conditions over which you have no control. This can range from a congenital disability to asthma. An estimated 133 million people—roughly half of all nonelderly people—have a pre-existing condition.

The ACA, starting in 2014, prohibited private health insurers from discriminating against people with pre-existing conditions. Insurers must offer the same benefits, at the same rates, with no waiting periods or denials. The law included other policies to help spread the cost of people with pre-existing conditions.

Prior to the ACA, insurers in most states could lower their cost through pre-existing condition exclusions. Thirty-five states ran high-risk pools for individuals affected by these practices. Virtually all of these high-risk pools had strict eligibility limits, high premiums, and limits on coverage. An estimated 226,615 people were covered in them.

Some proponents of traditional high-risk pools argue that they were inadequately funded. Yet, the ACA funded a $5 billion, nationwide high-risk pool to help uninsured people with pre-existing conditions before its reforms kicked in. Called the Pre-existing Condition Insurance Program (PCIP), it charged market premiums, had no waiting period or benefit carve outs, and operated from August 2010 through 2013.

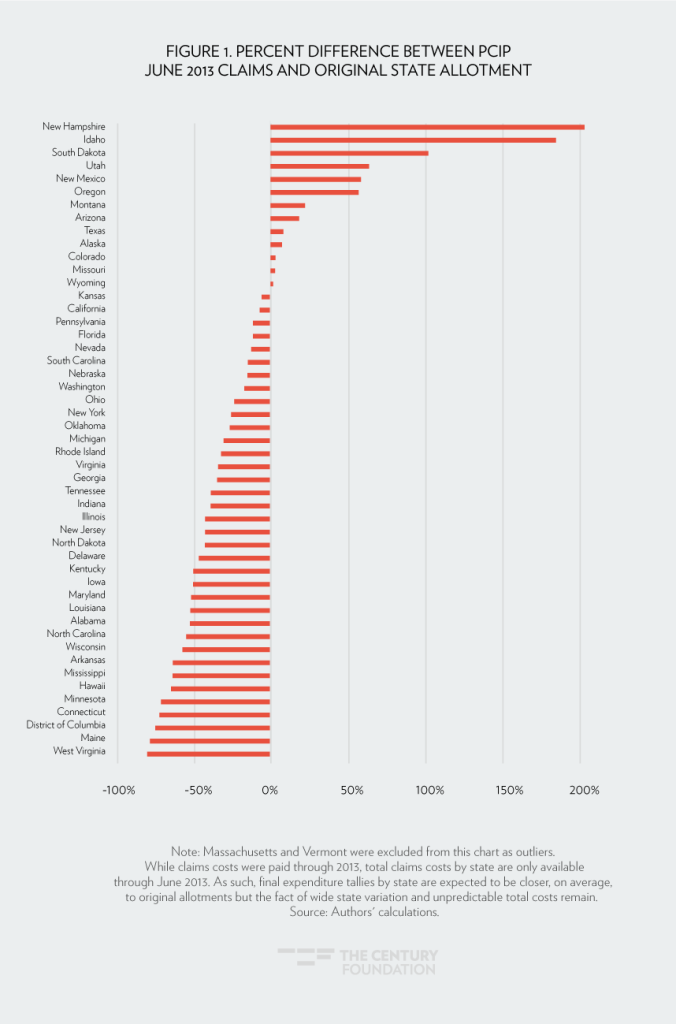

A Century Foundation report in 2017 assessed the performance of PCIP, concluding that its impact was limited. Despite helping about 135,000 people, it had fluctuating enrollment, was difficult to manage, and ultimately did little to lower premiums in the individual market. Actual spending was over twice as high as the pre-set allotment in one state, and was half of the pre-set allotments in seventeen other states. Even using the funding formula in the House Republican plan, allotments were plus or minus 20 percent different than actual spending in thirteen states (see Figure 1). Spending per enrollee also changed dramatically year over year, increasing or decreasing by more than 20 percent in twenty-four states. Predictable budgeting was impossible.

Other proponents suggest a related model: “invisible high-risk pools” such as used in one Maine program. The Maine program allowed insurers to send the premiums and claims of enrollees with one of eight conditions—or for any other reason—to a special reinsurance pool for payment of high claims. This pool also received fees from all insurance plans and federal subsidies. However, in 2022, Maine replaced this form of reinsurance with traditional claims-based reinsurance that treats all people enrolled in the health plan the same because it was more effective. Out of eighteen states, including seven states with Republican majorities in their state legislatures, only Alaska has a reinsurance program based purely on health conditions.

In short, high-risk pools—state-based pools, PCIP, or the invisible high-risk pool—have failed to effectively and efficiently cover people with pre-existing conditions. This is because they are based on a flawed concept, not because of their specific designs. By definition, a pool exclusively made up of people with high risk has high premiums, little leverage to negotiate prices, and wide swings in cost. And this concept ignores the capricious nature of health: a person in the pool may have surgery one day and become low risk the next day—and a person outside of the pool may be low risk one day but be diagnosed with cancer the next.

So, when House Speaker Mike Johnson threatens “massive reform” of the ACA by taking “a blowtorch to the regulatory state,” people with pre-existing conditions, beware. No concept of high-risk pool will replace the protections in place today.

Tags: affordable care act, pre-existing conditions, health coverage

Trump Presidency Puts Americans with Pre-Existing Conditions at Risk. Again.

Changes are on the horizon for Americans with pre-existing conditions under a Trump presidency. While Trump said he had only “concepts of a plan,” J.D. Vance stated on Meet the Press that the best approach to covering people is to “not have a one-size-fits-all approach that puts a lot of people into the same insurance pools, into the same risk pools.”

This likely translates into trying, again, to repeal the Affordable Care Act (ACA) provisions that mainstream people with pre-existing conditions into private health insurance.

Many of us have pre-existing conditions. They are generally defined as having a known health condition (or history of it) that requires costly treatment, including conditions over which you have no control. This can range from a congenital disability to asthma. An estimated 133 million people—roughly half of all nonelderly people—have a pre-existing condition.

The ACA, starting in 2014, prohibited private health insurers from discriminating against people with pre-existing conditions. Insurers must offer the same benefits, at the same rates, with no waiting periods or denials. The law included other policies to help spread the cost of people with pre-existing conditions.

Prior to the ACA, insurers in most states could lower their cost through pre-existing condition exclusions. Thirty-five states ran high-risk pools for individuals affected by these practices. Virtually all of these high-risk pools had strict eligibility limits, high premiums, and limits on coverage. An estimated 226,615 people were covered in them.

Some proponents of traditional high-risk pools argue that they were inadequately funded. Yet, the ACA funded a $5 billion, nationwide high-risk pool to help uninsured people with pre-existing conditions before its reforms kicked in. Called the Pre-existing Condition Insurance Program (PCIP), it charged market premiums, had no waiting period or benefit carve outs, and operated from August 2010 through 2013.

A Century Foundation report in 2017 assessed the performance of PCIP, concluding that its impact was limited. Despite helping about 135,000 people, it had fluctuating enrollment, was difficult to manage, and ultimately did little to lower premiums in the individual market. Actual spending was over twice as high as the pre-set allotment in one state, and was half of the pre-set allotments in seventeen other states. Even using the funding formula in the House Republican plan, allotments were plus or minus 20 percent different than actual spending in thirteen states (see Figure 1). Spending per enrollee also changed dramatically year over year, increasing or decreasing by more than 20 percent in twenty-four states. Predictable budgeting was impossible.

Other proponents suggest a related model: “invisible high-risk pools” such as used in one Maine program. The Maine program allowed insurers to send the premiums and claims of enrollees with one of eight conditions—or for any other reason—to a special reinsurance pool for payment of high claims. This pool also received fees from all insurance plans and federal subsidies. However, in 2022, Maine replaced this form of reinsurance with traditional claims-based reinsurance that treats all people enrolled in the health plan the same because it was more effective. Out of eighteen states, including seven states with Republican majorities in their state legislatures, only Alaska has a reinsurance program based purely on health conditions.

In short, high-risk pools—state-based pools, PCIP, or the invisible high-risk pool—have failed to effectively and efficiently cover people with pre-existing conditions. This is because they are based on a flawed concept, not because of their specific designs. By definition, a pool exclusively made up of people with high risk has high premiums, little leverage to negotiate prices, and wide swings in cost. And this concept ignores the capricious nature of health: a person in the pool may have surgery one day and become low risk the next day—and a person outside of the pool may be low risk one day but be diagnosed with cancer the next.

So, when House Speaker Mike Johnson threatens “massive reform” of the ACA by taking “a blowtorch to the regulatory state,” people with pre-existing conditions, beware. No concept of high-risk pool will replace the protections in place today.

Tags: affordable care act, pre-existing conditions, health coverage