Me llamo Josefina. Sí, it was a requirement to select an alter-ego of sorts for my high-school Spanish class. I chose the name from a list of other common Spanish names, like María and José.

Josefina had a good ring to it, and it followed me throughout my high school Spanish career, from freshman through junior year. I chose this name, but I was unconsciously confused and bothered. Jazmín, the direct Spanish equivalent of my true name, could have worked just fine. Instead, for every class assignment, dialogue and proyecto, I became Josefina.

Jasmine in Geometry, but Josefina in Spanish class. Jasmine in AP Biology, but Josefina in la clase de español. I could be myself in World History, but I was required to adopt my alternate, supposedly Latina personality when I crossed the threshold of Señora’s classroom.

I figured this was just how things go in a foreign language (now world language) class. I accepted it, and Spanish was still my favorite subject in school. The teacher was upbeat and I had always wanted to learn another language, so I soaked everything all in. Ultimately, I responded to my teacher and other classmates of Juans, Carloses, and Isabelas with acceptance and conformity as Josefina.

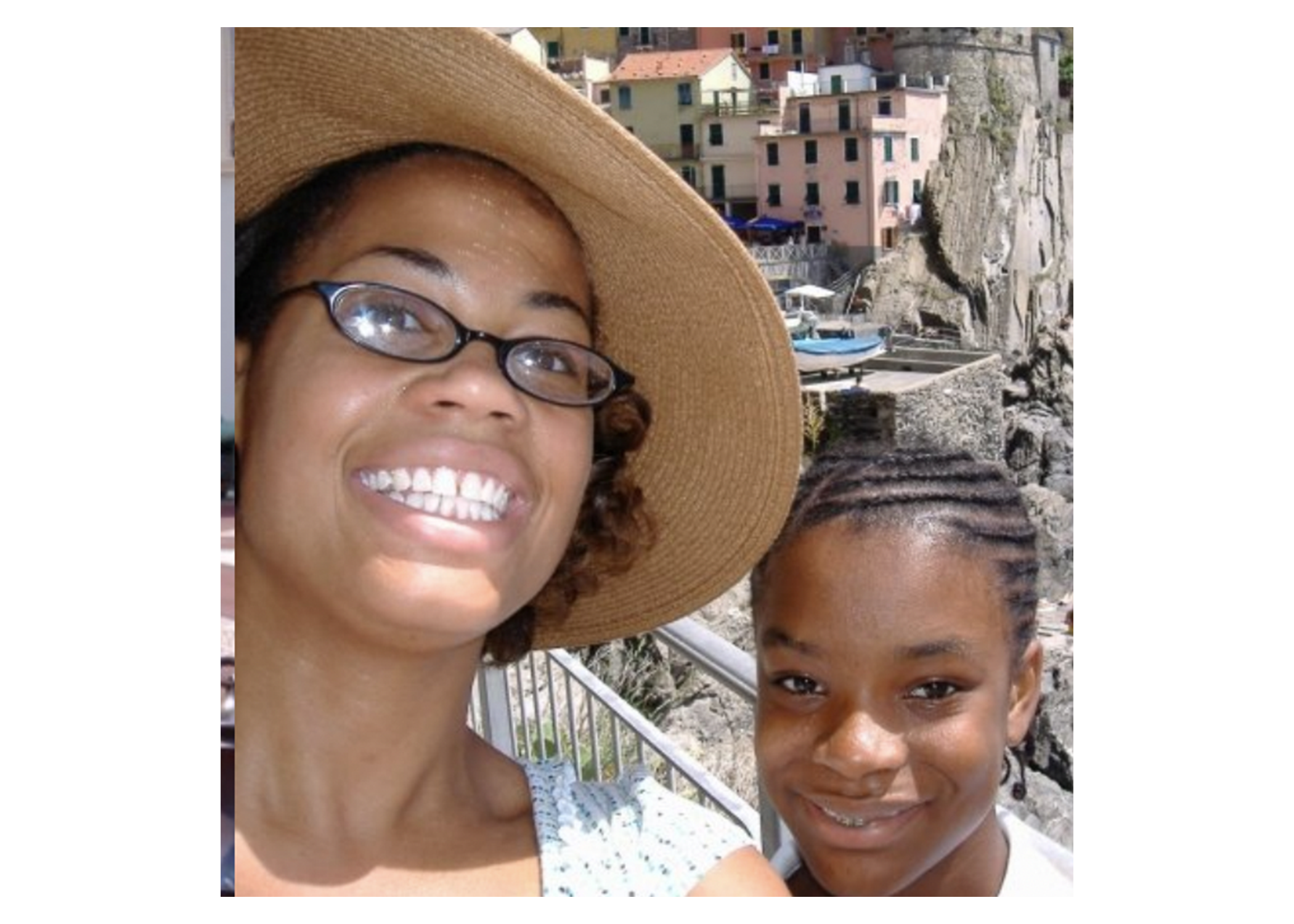

Principal Jasmine Brann (then high school teacher) and student at Cinque Terre in Italy. Summer 2007 on an international student tour she led. Source: Jasmine Brann.

Fast forward to college, during which I studied abroad in Argentina and France. Years later, as a Spanish and French teacher myself, I vowed to avoid this practice of innocuous self-sabotage. It erased my identity and who I was. Me llamo Jasmine and I am Black, multilingual, and multidimensional.The friction I felt at navigating these multiple identities was just one example of how multilingual learning can be challenging for schools and students navigating complex intersections of racial, ethnic, and linguistic diversity. The United States’ halting efforts to offer bilingual instruction in public schools have not often included—let alone welcomed—African-American communities. I continue to see more and more evidence that students like me are being left out of the city’s bilingual and dual-language immersion (DLI) programs.

Naturally, as an educator, I care about the future of language learning access, especially for the Black community, which has been historically left out of enriching international linguistic and cultural experiences.

This is why I feel the need to tell my story. Exploring other languages and cultures has not only afforded me the opportunity to appreciate others and their mores, but my diverse experiences have also deepened my own sense of self-discovery and actualization. Naturally, as an educator, I care about the future of language learning access, especially for the Black community, which has been historically left out of enriching international linguistic and cultural experiences.

Access to Bilingual Learning Can Help Close Equity Gaps

This is a major challenge in Washington, D.C., a city I love and where I work, as well as in other communities across the country. I am the principal and lead learner of Shirley Chisholm Elementary, a Title I school which has hosted two primary instructional strands since 2005: Creative Arts in English and Dual Language Spanish Immersion.

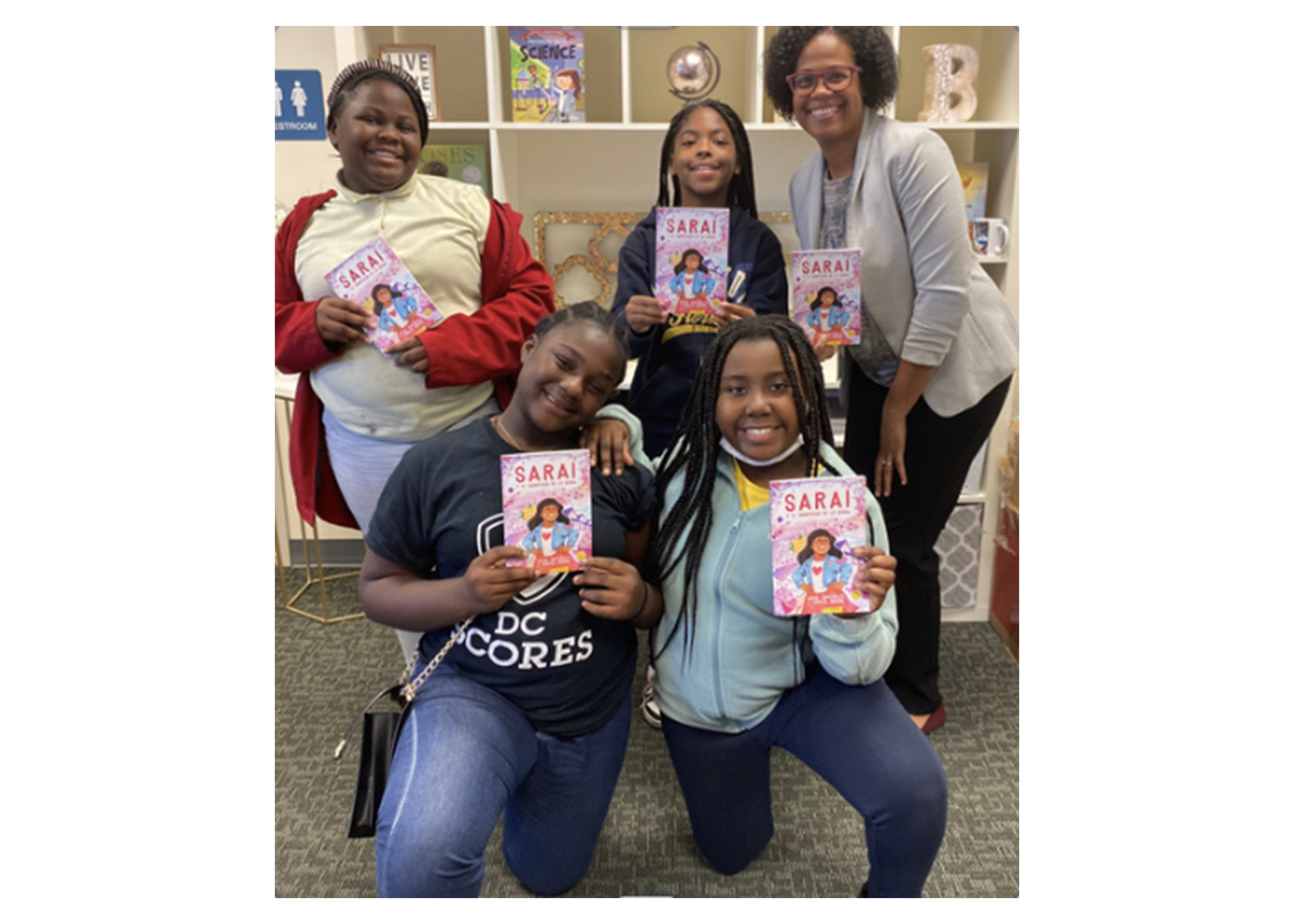

Principal Brann with fifth Graders in her Spanish lunch book club. Source: Jasmine Brann.

Recently, after years of community feedback and engagement, we completed the vision of integrating these two programs for the 2023–2024 school year, ensuring that all of our students—including the 62 percent of our students who are Black—have access both to world-class arts and bilingual instruction. Our unified Bilingual Arts program begins with our pre-school and pre-kindergarten classrooms and will phase up to fifth grade each year moving forward. Our neurodiverse learners also enjoy bilingual exposure within our innovative learning environment. Shirley Chisholm Elementary is proud to be a part of the efforts in U.S. public education to close pervasive opportunity and achievement gaps. High-quality language learning programs must be part of this pursuit. DLI programming has been associated with reductions in the achievement gap between English learners (ELs) and their native English-speaking counterparts across the country. According to the Center for Applied Linguistics (CAL), dual-language immersion programs offer an instructional model “in which the language goals are full bilingualism and biliteracy in English and a partner language, students study language arts and other academic content (math, science, social studies, arts) in both languages over the course of the program, the partner language is used for at least 50% of instruction at all grades, and the program lasts at least 5 years.”

Research heralds bilingualism as a fortifying cognitive measure, bestowing advantages like improved working memory, attention control, and decision-making abilities. Further, studies reliably show that bilingual instruction uniquely helps English learners learn English, succeed academically, and develop their emerging bilingual skills. If historically marginalized students gain access to programs that help them become bilingual, it may help remediate academic gaps in subjects like Math and Reading.

While language learning can confer these sorts of cognitive “superpowers,” the United States has not historically made multilingualism a priority. Fully 78 percent of the U.S. population speaks only English as of 2019, and only one in five K–12 U.S. students were studying a language other than English. Enrollment in world language college and university courses has also declined 29.3 percent from 2009 to 2021. Meanwhile, multilingualism is normalized all around the world: more than half of the global population is bilingual or even multilingual.

Now, thanks to advocates and the work that U.S. Secretary of Education Dr. Miguel Cardona’s “Raise the Bar” initiative has done to champion the cause, there is a growing emphasis on the value and benefits of language learning. But a question remains: How do we ensure that all students—in particular, English-dominant Black students from all walks of life—also have equal access to this beneficial learning experience?

Washington, D.C.’s Dual Language Immersion Programs Are Not Equitably Accessible

My educational home base, Washington, D.C., is diverse in every sense. Unfortunately, its current school systems and services are equally riven with historical educational inequities and iniquities that compound socioeconomic inequality in the city. Frustratingly, these systemic resource gaps often align with racial identities.

Local leaders are trying to change this status quo. Washington, D.C. offers newly modernized schools across all wards of the city, all-expense-paid international student field trips, and many opportunities for families to exercise choice in determining their children’s education experiences.

Nonetheless, the city still has wide gaps in student outcomes and experiences, gaps which are linked closely to race, demography, and socioeconomic status. In particular, White students outperformed Black students on Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College Careers (PARCC) 2023 (Level 4+) by 58.3 percent in English Language Arts and 63.3 percent in Math. Furthermore, ELs’ proficiency rates are currently outpacing Black students by more than 5 percent in their Math performance, per Washington, D.C.’s 2023 summative assessment.

Figure 1

With only 4 percent of Washington, D.C.’s more than 58,000 Black students enrolled in some form of DLI programming, the Black student majority is severely misrepresented. In fact, Black students in D.C. are 6.3 times less likely to be enrolled in a dual-language immersion program than their peers from other backgrounds. Despite being the minority in Washington, D.C. schools, because of gentrification and other inequitable factors, White and Asian students are overrepresented as English-dominant students in DLI programs: they’re 1.9 and 1.7 times more likely to be enrolled in these specialized programs, respectively.

These demographics mark an equity crisis.

Washington, D.C. is presented with both an obvious problem and an opportunity as it relates to language learning opportunities for Black students, who make up the predominant student demographic (66 percent) in the city’s schools.

Despite being the minority in Washington, D.C. schools, because of gentrification and other inequitable factors, White and Asian students are overrepresented as English-dominant students in DLI programs.

Somehow, here, in a city as diverse and globally important as Washington, D.C., access to bilingualism has become uniquely scarce and disproportionately inaccessible for Black students, the District’s largest student group. Black students also need these twenty-first-century competencies and experiences to be prepared in school, business, relationships, and the internationally competitive workforce. Given the gap-closing potential of these dual-language immersion programs, this must be a new and central priority for local education leaders.

The History (and Future) of Dual Language Programs in D.C.

In 1971, D.C. Public Schools created an experimental program for schools in the District’s Spanish-speaking communities to support the growing number of Spanish-dominant students in accessing academic content successfully while validating their home language. Spanish-speaking families had immigrated to the United States and settled in Adams Morgan and Mt. Pleasant after the Civil War in El Salvador. By the 1980s, Escuela Oyster (now Oyster-Adams) was one of the few bilingual schools across the country funded with not only government support, but also parents and partners who believed in this holistic model. As research has validated their approach, these programs have only grown in number in Washington, D.C.—and across the nation as well. These programs provide a linguistically rich language immersion experience, and therefore they have proven a highly successful model in supporting ELs’ linguistic and academic development, as well as in supporting all students in becoming balanced bilingual and biliterate individuals. Nowadays, dual language schools have become very attractive to parents who see the value of having their children learn a language other than English at an early age.

Hallway bulletin board outside of PK3 classroom. Every PK3 and PK4 student now learns in the new Bilingual Arts program at Shirley Chisholm Elementary. Source: Carolina Molina (teacher) and Shakia Walker (assistant teacher).

Of the more than 200 public and public charter schools in Washington, D.C., just twenty-five have dual-language immersion programming (in Spanish, French, Mandarin, and/or Hebrew). Simply put, the limited supply of DLI programs cannot yet meet the demand and provide easy access for interested families and students.

Students of all walks of life and backgrounds should be provided a holistic, rigorous curriculum to help them grow and flourish. We must continue to advocate, and legislate, for equitable language learning opportunities for all students. This can be accomplished through comprehensive efforts and strategies within our communities. First, we must continue to learn more about global education and its value for all students. We should remain curious about international pedagogies and dual-language immersion programs’ potential for advancing equitable educational outcomes.

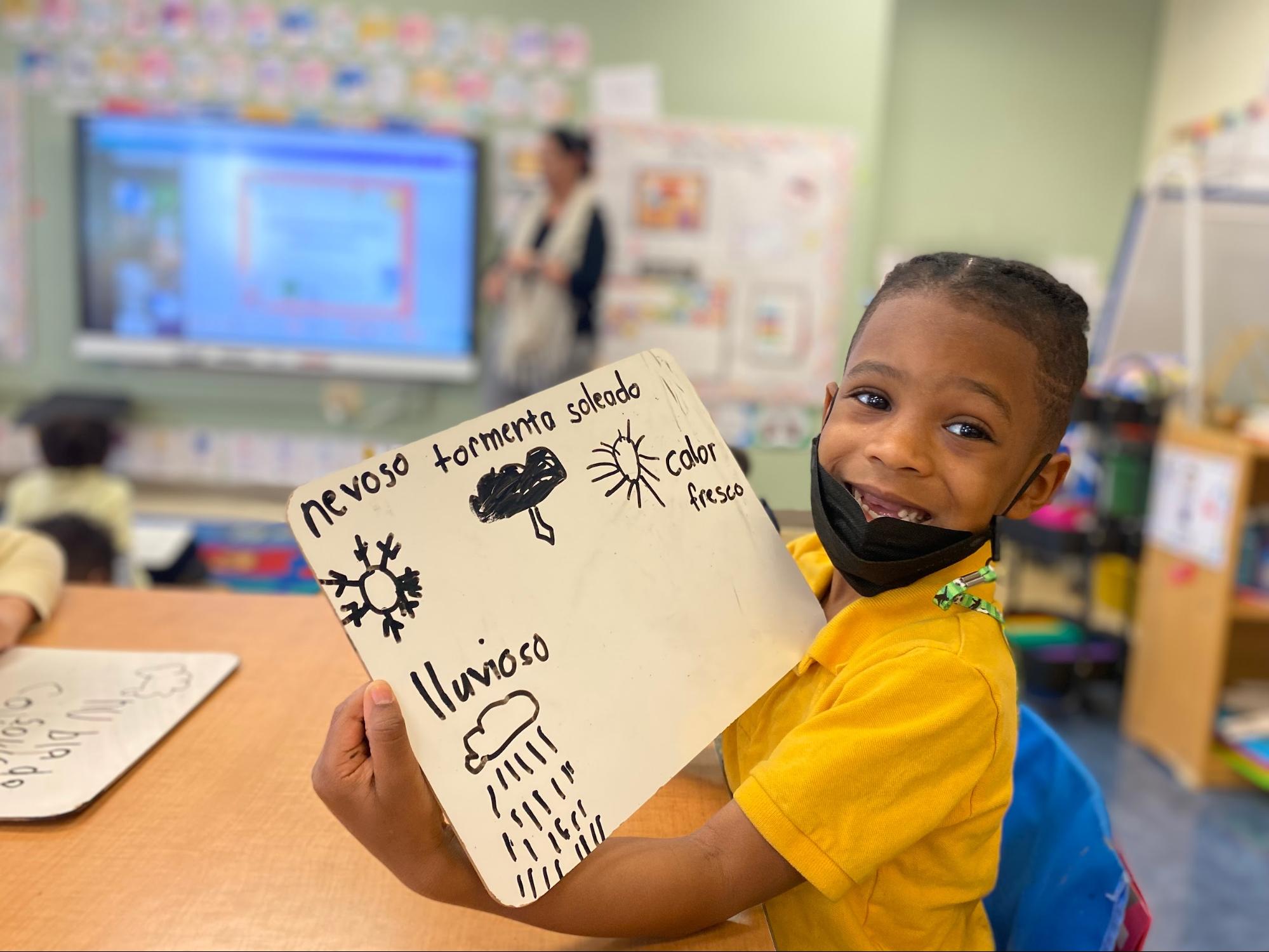

Kindergarten student, A.J., highlights his Spanish vocabulary and artistic skills. Source: Jasmine Brann

Second, we should increase our recruitment efforts to find more bilingual teachers—both internationally and by tapping our local talents. This will help us strengthen language learning programs so that we can focus on fortifying the structures that train and retain bilingual staff across multiple languages and cultures.

Because we can’t afford to wait, we have to simultaneously strive to reach our students who are so close, yet so far from opportunities due to economic circumstances. The District’s lottery preferences policy offering equitable access and designated seats for low-income students is a promising and transformative policy change. We are proud to have added this admissions preference for our school so that we can serve the beautiful, broad variety of learners in our neighborhood that much better.

Dual language immersion programming is a mode of high-quality language instruction intended to help students thrive in school and in life. Montessori, STEM, and other programmatic foundations can enrich students’ lives as well. So while language learning may not be the end-all, be-all, it definitely deserves more shine and attention at both the national and local level. And, as we consider illuminating who has access to these dual-language immersion programs and its critical importance as an integrative learning approach, let’s ensure Black students don’t get left in the shadows.

Tags: dual language education, bilingual education

The Bilingual Glow-Up: Why More Black Students Need Access to Language Programs in D.C.

Me llamo Josefina. Sí, it was a requirement to select an alter-ego of sorts for my high-school Spanish class. I chose the name from a list of other common Spanish names, like María and José.

Josefina had a good ring to it, and it followed me throughout my high school Spanish career, from freshman through junior year. I chose this name, but I was unconsciously confused and bothered. Jazmín, the direct Spanish equivalent of my true name, could have worked just fine. Instead, for every class assignment, dialogue and proyecto, I became Josefina.

Jasmine in Geometry, but Josefina in Spanish class. Jasmine in AP Biology, but Josefina in la clase de español. I could be myself in World History, but I was required to adopt my alternate, supposedly Latina personality when I crossed the threshold of Señora’s classroom.

I figured this was just how things go in a foreign language (now world language) class. I accepted it, and Spanish was still my favorite subject in school. The teacher was upbeat and I had always wanted to learn another language, so I soaked everything all in. Ultimately, I responded to my teacher and other classmates of Juans, Carloses, and Isabelas with acceptance and conformity as Josefina.

Principal Jasmine Brann (then high school teacher) and student at Cinque Terre in Italy. Summer 2007 on an international student tour she led. Source: Jasmine Brann.

Fast forward to college, during which I studied abroad in Argentina and France. Years later, as a Spanish and French teacher myself, I vowed to avoid this practice of innocuous self-sabotage. It erased my identity and who I was. Me llamo Jasmine and I am Black, multilingual, and multidimensional.The friction I felt at navigating these multiple identities was just one example of how multilingual learning can be challenging for schools and students navigating complex intersections of racial, ethnic, and linguistic diversity. The United States’ halting efforts to offer bilingual instruction in public schools have not often included—let alone welcomed—African-American communities. I continue to see more and more evidence that students like me are being left out of the city’s bilingual and dual-language immersion (DLI) programs.

This is why I feel the need to tell my story. Exploring other languages and cultures has not only afforded me the opportunity to appreciate others and their mores, but my diverse experiences have also deepened my own sense of self-discovery and actualization. Naturally, as an educator, I care about the future of language learning access, especially for the Black community, which has been historically left out of enriching international linguistic and cultural experiences.

Access to Bilingual Learning Can Help Close Equity Gaps

This is a major challenge in Washington, D.C., a city I love and where I work, as well as in other communities across the country. I am the principal and lead learner of Shirley Chisholm Elementary,1 a Title I school which has hosted two primary instructional strands since 2005: Creative Arts in English and Dual Language Spanish Immersion.

Principal Brann with fifth Graders in her Spanish lunch book club. Source: Jasmine Brann.

Recently, after years of community feedback and engagement, we completed the vision of integrating these two programs for the 2023–2024 school year, ensuring that all of our students—including the 62 percent of our students who are Black—have access both to world-class arts and bilingual instruction. Our unified Bilingual Arts program begins with our pre-school and pre-kindergarten classrooms and will phase up to fifth grade each year moving forward. Our neurodiverse learners also enjoy bilingual exposure within our innovative learning environment. Shirley Chisholm Elementary is proud to be a part of the efforts in U.S. public education to close pervasive opportunity and achievement gaps. High-quality language learning programs must be part of this pursuit. DLI programming has been associated with reductions in the achievement gap between English learners (ELs) and their native English-speaking counterparts across the country. According to the Center for Applied Linguistics (CAL), dual-language immersion programs offer an instructional model “in which the language goals are full bilingualism and biliteracy in English and a partner language, students study language arts and other academic content (math, science, social studies, arts) in both languages over the course of the program, the partner language is used for at least 50% of instruction at all grades, and the program lasts at least 5 years.”

Sign up for updates.

Research heralds bilingualism as a fortifying cognitive measure, bestowing advantages like improved working memory, attention control, and decision-making abilities. Further, studies reliably show that bilingual instruction uniquely helps English learners learn English, succeed academically, and develop their emerging bilingual skills. If historically marginalized students gain access to programs that help them become bilingual, it may help remediate academic gaps in subjects like Math and Reading.

While language learning can confer these sorts of cognitive “superpowers,” the United States has not historically made multilingualism a priority. Fully 78 percent of the U.S. population speaks only English as of 2019, and only one in five K–12 U.S. students were studying a language other than English. Enrollment in world language college and university courses has also declined 29.3 percent from 2009 to 2021. Meanwhile, multilingualism is normalized all around the world: more than half of the global population is bilingual or even multilingual.

Now, thanks to advocates and the work that U.S. Secretary of Education Dr. Miguel Cardona’s “Raise the Bar” initiative has done to champion the cause, there is a growing emphasis on the value and benefits of language learning. But a question remains: How do we ensure that all students—in particular, English-dominant Black students from all walks of life—also have equal access to this beneficial learning experience?

Washington, D.C.’s Dual Language Immersion Programs Are Not Equitably Accessible

My educational home base, Washington, D.C., is diverse in every sense. Unfortunately, its current school systems and services are equally riven with historical educational inequities and iniquities that compound socioeconomic inequality in the city. Frustratingly, these systemic resource gaps often align with racial identities.

Local leaders are trying to change this status quo. Washington, D.C. offers newly modernized schools across all wards of the city, all-expense-paid international student field trips, and many opportunities for families to exercise choice in determining their children’s education experiences.

Nonetheless, the city still has wide gaps in student outcomes and experiences, gaps which are linked closely to race, demography, and socioeconomic status. In particular, White students outperformed Black students on Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College Careers (PARCC) 2023 (Level 4+) by 58.3 percent in English Language Arts and 63.3 percent in Math. Furthermore, ELs’ proficiency rates are currently outpacing Black students by more than 5 percent in their Math performance, per Washington, D.C.’s 2023 summative assessment.

Figure 1

With only 4 percent of Washington, D.C.’s more than 58,000 Black students enrolled in some form of DLI programming, the Black student majority is severely misrepresented. In fact, Black students in D.C. are 6.3 times less likely to be enrolled in a dual-language immersion program than their peers from other backgrounds. Despite being the minority in Washington, D.C. schools, because of gentrification and other inequitable factors, White and Asian students are overrepresented as English-dominant students in DLI programs: they’re 1.9 and 1.7 times more likely to be enrolled in these specialized programs, respectively.

These demographics mark an equity crisis.

Washington, D.C. is presented with both an obvious problem and an opportunity as it relates to language learning opportunities for Black students, who make up the predominant student demographic (66 percent) in the city’s schools.

Somehow, here, in a city as diverse and globally important as Washington, D.C., access to bilingualism has become uniquely scarce and disproportionately inaccessible for Black students, the District’s largest student group. Black students also need these twenty-first-century competencies and experiences to be prepared in school, business, relationships, and the internationally competitive workforce. Given the gap-closing potential of these dual-language immersion programs, this must be a new and central priority for local education leaders.

The History (and Future) of Dual Language Programs in D.C.

In 1971, D.C. Public Schools created an experimental program for schools in the District’s Spanish-speaking communities to support the growing number of Spanish-dominant students in accessing academic content successfully while validating their home language. Spanish-speaking families had immigrated to the United States and settled in Adams Morgan and Mt. Pleasant after the Civil War in El Salvador. By the 1980s, Escuela Oyster (now Oyster-Adams) was one of the few bilingual schools across the country funded with not only government support, but also parents and partners who believed in this holistic model. As research has validated their approach, these programs have only grown in number in Washington, D.C.—and across the nation as well. These programs provide a linguistically rich language immersion experience, and therefore they have proven a highly successful model in supporting ELs’ linguistic and academic development, as well as in supporting all students in becoming balanced bilingual and biliterate individuals. Nowadays, dual language schools have become very attractive to parents who see the value of having their children learn a language other than English at an early age.

Hallway bulletin board outside of PK3 classroom. Every PK3 and PK4 student now learns in the new Bilingual Arts program at Shirley Chisholm Elementary. Source: Carolina Molina (teacher) and Shakia Walker (assistant teacher).

Of the more than 200 public and public charter schools in Washington, D.C., just twenty-five have dual-language immersion programming (in Spanish, French, Mandarin, and/or Hebrew). Simply put, the limited supply of DLI programs cannot yet meet the demand and provide easy access for interested families and students.

Students of all walks of life and backgrounds should be provided a holistic, rigorous curriculum to help them grow and flourish. We must continue to advocate, and legislate, for equitable language learning opportunities for all students. This can be accomplished through comprehensive efforts and strategies within our communities. First, we must continue to learn more about global education and its value for all students. We should remain curious about international pedagogies and dual-language immersion programs’ potential for advancing equitable educational outcomes.

Kindergarten student, A.J., highlights his Spanish vocabulary and artistic skills. Source: Jasmine Brann

Second, we should increase our recruitment efforts to find more bilingual teachers—both internationally and by tapping our local talents. This will help us strengthen language learning programs so that we can focus on fortifying the structures that train and retain bilingual staff across multiple languages and cultures.

Because we can’t afford to wait, we have to simultaneously strive to reach our students who are so close, yet so far from opportunities due to economic circumstances. The District’s lottery preferences policy offering equitable access and designated seats for low-income students is a promising and transformative policy change. We are proud to have added this admissions preference for our school so that we can serve the beautiful, broad variety of learners in our neighborhood that much better.

Dual language immersion programming is a mode of high-quality language instruction intended to help students thrive in school and in life. Montessori, STEM, and other programmatic foundations can enrich students’ lives as well. So while language learning may not be the end-all, be-all, it definitely deserves more shine and attention at both the national and local level. And, as we consider illuminating who has access to these dual-language immersion programs and its critical importance as an integrative learning approach, let’s ensure Black students don’t get left in the shadows.

Notes

Tags: dual language education, bilingual education