Foreword

After decades in the political wilderness, school integration seems poised to make a serious comeback as an education reform strategy.

Sixty-two years ago, Brown v. Board of Education held that separate schools for black and white students are inherently unequal. Fifty years ago, the evidence in the congressionally authorized Coleman Report put a twist on Brown, suggesting that socioeconomic school integration could increase academic achievement more than any other school strategy. But when racial school desegregation began to be seriously pursued in the early 1970s, the implementation was often clumsy. Federal judges ordered school children to travel across town to attend schools to achieve racial balance, giving parents no say in the matter. Families rebelled.

And so for years, we have been stuck with a tragic paradox: building on Coleman’s findings, a growing body of research produced a social science consensus that school integration—by race and by socioeconomic status—is good for children. Simultaneously, an equally durable political consensus developed holding that nothing can be done to achieve it.

Layered on top of political concerns was a new legal challenge. The Supreme Court, once a strong supporter of school desegregation, grew increasingly skeptical of government programs that use race in decision-making. In a 2007 ruling, the Roberts Court struck down voluntary school desegregation efforts in Louisville and Seattle. To some, the decision seemed to spell the end to school desegregation.

Today, however, school integration—using new, more legally and politically palatable approaches—is getting a second look as an educational reform strategy.

For one thing, policymakers and scholars across the political spectrum are beginning to realize that ignoring the social science research on the negative effects of concentrated school poverty is not working to close large achievement gaps between races and economic groups. Diane Ravitch and Michelle Rhee—who represent opposite ends of our polarized debates over education reform—have both recently advocated new measures to promote school integration to raise the achievement of disadvantaged students.

What can give integration real political momentum, however, are not the documented benefits to low-income students, but the emerging recognition that middle- and upper-class students benefit in diverse classrooms.

As Amy Stuart Wells, Lauren Fox, and Diana Cordova-Cobo of Teachers College Columbia vividly demonstrate in this important new report, “the benefits of school diversity run in all directions.” There is increasing evidence that “diversity makes us smarter,” a finding that selective colleges long ago embraced and increasing numbers of young parents are coming to appreciate at the K–12 level. The authors write: “researchers have documented that students’ exposure to other students who are different from themselves and the novel ideas and challenges that such exposure brings leads to improved cognitive skills, including critical thinking and problem solving.”

Apart from the cognitive benefits, there are additional reasons increasing numbers of middle-class families now want to send their children to diverse schools. Middle-class and white Millennials realize that their children are growing up in a very different country, demographically, than previous generations. For the first time since the founding of the republic, a majority of public school K–12 pupils in the United States are students of color.

Students can learn better how to navigate adulthood in an increasingly diverse society—a skill that employers value—if they attend diverse schools. Ninety-six percent of major employers, Wells, Fox, and Cordova-Cobo note, say it is “important” that employees be “comfortable working with colleagues, customers, and/or clients from diverse cultural backgrounds.”

Adding to the political momentum behind integration are changes in the choices middle-class families are making in where to live. In previous generations, when poor urban areas were often surrounded by wealthy white suburbs, achieving school integration was logistically challenging and involved long bus rides that were unpopular with families.

Today, however, many middle-class Millennials say they find suburban life sterile and prefer walkable communities. One poll, the authors note, found that 77 percent of Millennials expressed a preference for urban life. This development raises new possibilities for integrated schooling.

Adding further to the political and legal sustainability of integration is the emergence of new policies that rely on choice and incentives rather than compulsory busing, and that use socioeconomic rather than racial indicators as the primary basis for integration.

New policies rarely rely on compulsory busing of the type used in 1970s, the authors point out. They note, for example, that more than forty interdistrict magnet schools have been created in the Hartford, Connecticut region to serve 16,000 students in schools with distinctive pedagogical or thematic approaches that are filled through voluntary choice.

New policies that emphasize socioeconomic status avoid the legal impediments to using race, and connect to Coleman’s research findings, replicated in subsequent studies, that the socioeconomic status of classmates is a critical driver of student achievement.

When The Century Foundation (TCF) commissioned me to write a book about socioeconomic school integration in 1996, just two districts in the nation, educating about 30,000 students, were pursuing such policies. Today, as TCF’s Halley Potter and Kimberly Quick demonstrate in a new paper, “A New Wave of School Integration,” the number of districts and charter school chains using socioeconomic status as a factor in student assignment has risen to ninety-one. Located in thirty-two states, both red and blue, these districts educate some 4 million students.

One particularly innovative example can be found in New York State, where the commissioner of education (now acting U.S. secretary of education) John King created a socioeconomic integration pilot program to turn around struggling schools. Rather than firing teachers or bringing in charter school operators, as is common in many school turnaround efforts, King’s innovative program seeks to invigorate schools with a broad cross section of students.

New policies—emphasizing choice and socioeconomic status—are proving popular among a new generation of parents. Wells, Fox and Cordova-Cobo point, for example, to a remarkable change in attitudes in Louisville, Kentucky. In the early 1970s, compulsory busing for racial desegregation was opposed by 98 percent of parent. By 2011, a choice-based system emphasizing socioeconomic alongside racial integration was supported by 89 percent of parents.

With leadership, such success stories can be replicated to help us move, at long last, beyond separate and unequal to something far better for all American students.

Introduction

A growing number of parents, university officials, and employers want our elementary and secondary schools to better prepare students for our increasingly racially and ethnically diverse society and the global economy. But for reasons we cannot explain, the demands of this large segment of Americans have yet to resonate with most of our federal, state, or local policymakers. Instead, over the past forty years, these policy makers have completely ignored issues of racial segregation while focusing almost exclusively on high-stakes accountability, even as our schools have become increasingly segregated and unequal.

This report argues that, as our K–12 student population becomes more racially and ethnically diverse, the time is right for our political leaders to pay more attention to the evidence, intuition, and common sense that supports the importance of racially and ethnically diverse educational settings to prepare the next generation. It highlights in particular the large body of research that demonstrates the important educational benefits—cognitive, social, and emotional—for all students who interact with classmates from different backgrounds, cultures, and orientations to the world. This research legitimizes the intuition of millions of Americans who recognize that, as the nation becomes more racially and ethnically complex, our schools should reflect that diversity and tap into the benefits of these more diverse schools to better educate all our students for the twenty-first century.

The advocates of racially integrated schools understand that much of the recent racial tension and unrest in this nation—from Ferguson to Baltimore to Staten Island—may well have been avoided if more children had attended schools that taught them to address implicit biases related to racial, ethnic, and cultural differences. This report supports this argument beyond any reasonable doubt.

Why the Emphasis on the Educational Benefits of Diversity Now?

The call for more attention to intense racial segregation in our nation’s schools and communities is coming from parents, educators, and employers who are realigning their priorities and understandings in light of our increasingly global economy and the rapid changes in our nation’s demographics and migration patterns.1 For the first time, the K–12 student population in the United States is less than 50 percent white, non-Hispanic. Meanwhile, in many of our major metropolitan areas, we see large-scale migration patterns, as more black, Hispanic, and Asian families move to the suburbs and more whites return to “gentrifying” urban neighborhoods. In both contexts, de facto diverse communities are forming, if only temporarily, before patterns of racial segregation re-emerge.2 These recent developments suggest we are at a critical moment in history—at a juncture between a future of more racial unrest and a future of racial healing when our society can become less divided and more equal. It is also clear from our history that absent strong leadership at the federal, state, and local level to sustain diverse neighborhoods and schools, it is likely we will recreate high levels of racial segregation in both urban and suburban contexts.3

In this report, we review the research and reasons why, in the field of education in particular, policy makers should listen to the growing demand for more diverse public schools. Drawing on the research from both higher education and K–12 education, we demonstrate that there are important educational benefits to learning in environments with peers who grew up on the other side of the racial divide in this country. Indeed, in recent years, most of this research on the “educational benefits of diversity” has been conducted in colleges and universities and then put forth as powerful evidence to support affirmative action in higher education.

This year, as the U.S. Supreme Court considers affirmative action once again in the Fisher v. University of Texas4 case (Fisher II), it is an important moment to consider how those arguments translate into the K–12 educational context. In fact, researchers, policy makers, and educators in K–12 were, once upon a time, much more focused on the problem of racial segregation than they have been in recent decades. This shift in focus is due in large part, we argue, to the changing policy context in elementary and secondary education over the last several decades—away from school desegregation policy and toward a focus on outcomes and accountability in racially, ethnically, and socioeconomically segregated settings. In fact, the emphasis in K–12 education on narrow student achievement measures has moved the entire field away from examining cultural issues related to race, ethnicity, and the social and emotional development of children.5 Given the demographic and attitudinal changes discussed above, now is the time to refocus the K–12 agenda on issues of racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic integration and the educational benefits that accrue from students learning from each other in diverse schools and classrooms. We use the term racial “integration” and not “desegregation” to convey that we mean something more than merely moving students to balance racial enrollments. When we discuss the research evidence on the educational benefits of diversity, we are talking about a more meaningful form of racial and ethnic integration, leading to greater mutual respect, understanding, and empathy across racial lines.6

This report provides an overview of the forces within the K–12 educational system—demographic, educational, and political—that could help move our public school system into the twenty-first century on issues of racial/ethnic diversity and the educational benefits of teaching and learning in diverse schools and classrooms. While we do not deny the many factors working against the creation and sustainability of more diverse schools and classrooms, we believe that K–12 researchers, policy makers, and parents should pay more attention to the arguments put forth in higher education court cases regarding the educational benefits to all students. Furthermore, we argue that there already exists a body of research in K–12 education that similarly supports an argument in favor of the educational benefits of diversity, but that unlike the higher education research, it has been largely ignored in recent years.

In light of recent events of racial profiling, police shootings, campus unrest, and the rise of a movement that sadly seeks to remind us of the self-evident fact that “Black Lives Matter,” such interracial respect, understanding, and empathy is what we should all strive for in our increasingly diverse society. There is no institution better suited to touch the lives of millions of members of the next generation than our public schools. This report will give voice to the millions who can envision this future for K–12 education and help us get there.

Evidence on the Educational Benefits of Diversity

Tracing the history of public policies to create racially diverse schools and universities in America—most notably school desegregation in K–12 and affirmative action in higher education—from the mid-twentieth through the early twenty-first century, we see important distinctions between these two educational sectors. These distinctions help us explain why, at a time of increasing racial and ethnic diversity in the school age and young adult population in the United States, the policies of K–12 and higher education seem so completely disconnected regarding how to address these demographics changes.

We argue that particularly in the last twenty-five years, the higher education and K–12 paths have drifted apart on the issues of campus, school, and classroom level diversity (see Figure 1). This difference is grounded in at least two key factors:

1. The Research-Jurisprudence Alliance in Higher Education. An alliance of the higher education jurisprudence on affirmative action, and the higher education research on the educational benefits of diversity has strengthened colleges and universities’ commitment to racially diverse student bodies and educational settings in which students learn from each other across cultural boundaries.

In the K–12 arena, on the other hand, the jurisprudence and the research alliances around school desegregation policy have focused less on the educational benefits of diverse classrooms in which students can learn from classmates with different backgrounds and perspectives and more on the potentially beneficial “outcomes” of racially balanced or “desegregated” public schools as measured by test scores, graduation rates, and the like. These benefits are real and substantial, but this focus on student outcomes almost exclusively as the central measure of equal educational opportunity, has, in the long run, led to less emphasis on the educational experiences of students in racially diverse schools and classroom, and thus, fewer efforts to support integration efforts.

2. The Recent Policy Context of K–12 Education. There are several political reasons for the distinctions between higher education and K–12 education, not the least of which is the heavy-handed, test-based accountability system that has been implemented in the K–12 system over the last twenty-five years. In this era of what some have referred to as “neo-Plessyism”—an emphasis on “separate but equal”—in K–12 education, the policy focus has been on educating all students to high standards and closing achievement gaps as measured by standardized tests wherever they are, in racially isolated schools or not. In fact, many policy makers on both sides of the aisle believe the standards and accountability movement should assure that all students have access to a challenging curriculum, no matter what the racial make-up of their classmates may be.7

This policy context, coupled with the place-based nature of K–12 education amid severe residential segregation, highly fragmented school districts, and the limitations on interdistrict desegregation remedies after the 1974 Supreme Court decision in Milliken v. Bradley,8 add up to a public educational system that is simultaneously becoming increasingly diverse in terms of its student population and increasingly segregated and unequal.9

Figure 1.

In other words, in the past few decades, prominent higher educational leaders, lawyers, and researchers have worked together to support race-conscious admissions policies, allowing college campuses to remain more racially and culturally diverse than most of the public schools their students attended prior to attending college. Meanwhile, college admissions offices and campus tour guides consistently cite the diversity of the student body as a major asset that enhances the learning of all students in higher education. While our colleges and universities still have much work to do to make their campuses more diverse and more welcoming to students of all racial, ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds, at least there has been institutional support for race-conscious admissions policies, which is a sharp contrast to the policy focus in K–12 education for the past twenty-five years. The question then becomes: How might K–12 educational policy makers and researchers play a role in bridging the higher education-K–12 divide on these issues?

Takeaways from the Higher Education Research on the Educational Benefits of Diversity for K–12 Educational Policy and

Since the Regents of the University of California v. Bakke10 Supreme Court ruling in 1978, federal judges’ understanding of the societal value of racially, ethnically, and culturally diverse university campuses has been strongly influenced by social science research on the positive relationship between student learning and exposure to peers of different backgrounds.11 This research continues to inform jurisprudence and public policy on affirmative action in higher education.12

Thus, in recent years, when federal judges have been less likely to support remedial arguments for affirmative action in higher education,13 the research on the “educational benefits of diversity” has become even more central to legal arguments put forth by universities whose race-conscious affirmative action policies are being challenged by white plaintiffs. These arguments are couched in a First Amendment argument about the rights of universities to define their educational settings, an argument put forth by university leaders and grounded in social science research.14 For instance, in an amicus brief filed in the Fisher II (2015) case this fall, a group of highly selective institutions, including Brown, Columbia, Princeton, Stanford, and Yale Universities, strongly supported race-conscious admissions policies intended to make their student bodies more racially and ethnically diverse.

Buttressing these arguments on the part of the universities is a growing body of evidence demonstrating several key academic and social outcomes related to student diversity on college campuses. The central takeaway from this scholarship is that students who attend colleges and universities with more racially and ethnically diverse student bodies are said to be exposed to a wider array of experiences, outlooks, and ideas that can potentially enhance the education of all students.15 In fact, the majority of amicus briefs filed in the Fisher II case prior to oral arguments before the U.S. Supreme Court support, bolster, and enhance prior research findings demonstrating the educational benefits of racially and ethnically diverse college campuses.16 Below we present key quotes and highlights from these briefs, organized into the most positive outcomes for all students on diverse campuses:

Enhanced Learning Outcomes for Students in Diverse Educational Contexts

Several amicus briefs in the Fisher II case underscore that research more strongly than ever supports the benefits of college diversity and demonstrates that exposure to diversity enhances critical thinking and problem-solving ability, while also improving several other attributes related to academic success, including student satisfaction and motivation, general knowledge, and intellectual self-confidence.17 One brief states “a diverse student population creates a richer learning environment because students learn most from those who have very different life experiences from theirs.”18

Another brief argues that researchers have documented that students’ exposure to other students who are different from themselves and the novel ideas and challenges that such exposure brings leads to improved cognitive skills, including critical thinking and problem-solving.19 In addition, there is evidence that college students who experience positive interactions with students from different racial backgrounds results in more open minds and engaging classroom conversations. And improved learning actually occurs in these classrooms because abstract concepts are tied directly to concrete examples drawn from a range of experiences.20

Beyond the ways that diversity helps all higher education students, there are benefits for “nonminority” white students specifically, as well as students of color. For instance, the American Psychological Association’s brief reviewed evidence that the “negative effects associated with insufficient racial diversity extend to members of nonminority groups,” most notably the persistence of implicit bias toward members of minority racial groups that interferes with the educational process. Recent events across the country concerning policing and campus unrest have raised more awareness of implicit, subconscious biases and how they can produce discriminatory behavior. Indeed, the APA’s brief notes that implicit biases can also disrupt cognitive functioning for members of both the majority and minority, as well-intentioned students exert significant mental effort “in order to combat the expression of stereotypes and negative attitudes that are often activated automatically and unintentionally.”21 Efforts to manage negative thoughts inhibit mental capacity by occupying the brain’s executive function and depleting cognitive resources related to attention and control.22 Proactive efforts to increase campus diversity can significantly reduce this implicit bias and its detrimental effects.23 White students in particular benefit from racially and ethnically diverse learning contexts in that the presence of students of color stimulates an increase in the complexity with which students—especially white students—approach a given issue. When white students are in racially homogeneous groups, no such cognitive stimulation occurs. Research shows that “the mere inclusion of different perspectives, and especially divergent ones, in any course of discussion leads to the kind of learning outcomes (for example, critical thinking, perspective-taking) that educators, regardless of field, are interested in.”24

Diversity benefits that are more specific to the academic benefits of students of color include the decreased risk of experiencing stereotyping and discrimination, which can otherwise undermine black, Latino, and Asian students’ academic achievement on less diverse college campuses. “Isolation, subordination, and negative stereotyping are commonplace in settings where minority numbers are especially low and the norms and behaviors of majority groups dominate.”25 These experiences become less prevalent and less detrimental to black, Latino, and Asian students when campuses are more diverse and minority students are not tokens, thereby enhancing their learning experience and outcomes.

Increased Intercultural and Cross-Racial Knowledge, Understanding, and Empathy

In addition to the robust social science evidence on the positive relationship between student body diversity and academic outcomes, there is a similarly impressive body of research supporting the correlation between campus and classroom diversity and an enhanced ability of students to exhibit interracial understanding, empathy, and an ability to live with and learn from people of diverse backgrounds. The amicus brief filed by Brown and other elite universities in the Fisher II case highlights that “diversity encourages students to question their assumptions, to understand that wisdom may be found in unexpected voices, and to gain an appreciation of the complexity of today’s world.”26 Other research includes analyses of how racially diverse educational settings are effective in reducing prejudice, by promoting greater contact between students of different races—both informally and in classroom settings—and by encouraging relationships and friendships across group lines.27

The takeaway for policy makers in the K–12 education context is that there is extensive and solid evidence that intergroup contact and cross-racial interaction improves interracial attitudes toward an entire group and reduces prejudice and the implicit biases discussed above.28 Indeed, as we discuss below, research on these issues in K–12 education with similar findings was, at one time, far more central to policy debates in elementary and secondary education.

Better Preparation for Employment in the Global Economy

Throughout the recent briefs in the Fisher II case, and building on an already rich body of social science evidence amassed for this and prior affirmative action cases, university officials and business leaders argue that diverse college campuses and classrooms prepare students for life, work, and leadership in a more global economy by fostering leaders who are creative, collaborative, and able to navigate deftly in dynamic, multicultural environments.29

A brief filed by nearly half of the Fortune 100 companies, including Apple, Johnson & Johnson, and Starbucks, argued that to succeed in a global economy, they must hire highly trained employees of all races, religions, cultures, and economic backgrounds. They noted that it is also critical that “all of their university-trained employees” enter the workforce with experience in sharing ideas, experiences, viewpoints, and approaches with diverse groups of people. In fact, such cross-cultural skills are a “business and economic imperative,” given that they must operate in national and global economies that are increasingly diverse. A workforce trained in a diverse environment is critical to their business success. Such college graduates, companies argue, provide more creative approaches to problem-solving by integrating different perspectives and moving beyond linear, conventional thinking. Employees are:

better equipped to understand a wider variety of consumer needs, including needs specific to particular groups, and thus to develop products and services that appeal to a variety of consumers and to market those offerings in appealing ways; they are better able to work productively with business partners, employees, and clients in the United States and around the world; and they are likely to generate a more positive work environment by decreasing incidents of discrimination and stereotyping.30

Diverse educational environments also enhance students’ leadership skills, among other skills that are helpful when working in racially, ethnically, and culturally diverse workplaces. A longitudinal study found that the more often first-year college students are exposed to diverse educational settings, the greater their “gains in leadership skills, psychological well-being, intellectual engagement, and intercultural effectiveness.”31 Indeed, the APA brief argues, in addition to obvious academic pursuits, colleges and universities also prepare students to be effective economic and political leaders on local, national, and global levels. “Effective leadership begins with prejudice reduction.”32

Increased “Democratic Outcomes,” including Engagement in Political Issues and Participation in Democratic Processes

And finally, students’ experiences in diverse classrooms can provide the kind of cross-cultural dialogue that prepares them for citizenship in a multifaceted society.33 Students develop improved civic attitudes toward democratic participation, civic behaviors such as participating in community activities, and intentions to participate in civic activities resulting from diverse learning experiences. One meta-analysis synthesized twenty-seven studies on the effects of diversity on civic engagement and concluded that college diversity experiences are, in fact, positively related to increased civic engagement.

The four findings listed above are the most robust, but there is additional evidence of other positive results that flow from creating racially, ethnically, and culturally diverse learning environments for students. Research clearly and strongly supports a legal or policy argument in favor of greater student diversity on college campuses as a mechanism to potentially enhance the educational experiences of all students.34 And this is not solely the conclusion of those who study higher education. Drawing on decades of research from organizational scientists, psychologists, sociologists, economists, and demographers, an article in Scientific American argues that diversity even enhances creativity and actually encourages the search for novel information and perspectives, leading to better decision making and problem solving. Therefore, diversity can improve the bottom line of companies and lead to unfettered discoveries and breakthrough innovations. “Even simply being exposed to diversity can change the way you think.”35

Moving from Whether to How

As the list of benefits of diversity in higher education and in the workplace continue to accrue, diversity on college campuses is seen not just as an end in and of itself, but rather an educational process. In fact, some research in higher education has shifted away from questions about whether students benefit from diverse learning environments in their post-secondary institutions to questions about how universities can foster the best conditions to maximize that impact.36

Hopefully, the question of how universities and their faculty can support the development of these educational benefits in classrooms and assignments will foster an examination of the level and nature of student engagement in the learning process. For instance, diverse student bodies in higher education classrooms are more likely to produce the above-noted outcomes when group discussions in classrooms are focused on an issue with generally different racial viewpoints—for example, the death penalty.37 Indeed, students benefit the most from racially and ethnically diverse campuses—inside and outside the classroom—when a set of mutually supportive and reinforcing experiences occur.38 These research findings should help inform higher education officials when they consider and address the type of student frustration and campus unrest we have witnessed at the University of Missouri, Yale, and Princeton in recent months. This shifts discourse from an emphasis on what students know to an additional focus on whether they know how to think and, more importantly, whether they are acquiring the skills needed to live and work in the twenty-first century. A twenty-first century education, it’s argued, is best accomplished through intentional educational practices that are integrated in nature, provide experiences that challenge students’ own embedded world views, and encourage application of knowledge to contemporary problems.39

These new developments in higher educational research on how to foster the educational benefits of diversity are still evolving and in many ways actually pick up where the K–12 research left off in the 1990s, during which the policy focus for elementary and secondary education shifted away from issues of racial and ethnic diversity. In the following section we consider the evidence—old and new—within the K–12 research literature that we argue can be more tightly connected to and inspired by the important higher education work on diversity and learning.

The K–12 Educational Research on School Desegregation Outcomes

A robust body of research related to K–12 school desegregation and its positive outcomes was developed following the success of federal courts and officials in implementing more than three hundred school desegregation plans in the 1970s and 1980s. This included an examination of both the short- and long-term outcomes of attending racially and socioeconomically integrated schools. The main focus of most of this research, however, has been on the short-term academic performance (measured primarily by test scores) of students attending racially diverse versus racially segregated schools. Many studies have examined the impact of school desegregation on the achievement of African American students; some have also measured outcomes on other racial/ethnic groups. An examination of issues related to the “educational benefits of diversity” has included looking at the relationship between attending a desegregated public school and students’ social and civic engagement, inter-group relations, emotional well-being, and life course trajectories.40

Closing the Achievement Gap

The bulk of the K–12 educational research on the impact of school racial and socioeconomic composition on measurable academic outcomes documents that attending racially segregated, high-poverty schools has a strong negative association with students’ academic achievement (often measured through grade-level reading and math test scores).41 Attending racially diverse schools is beneficial to all students and is associated with smaller test score gaps between students of different racial backgrounds, not because white student achievement declined, but rather that black and/or Hispanic student achievement increased.42 In fact, the racial achievement gap in K–12 education closed more rapidly during the peak years of school desegregation than they have overall during the more recent era in which desegregation policies were dismantled and replaced by accountability policies.43

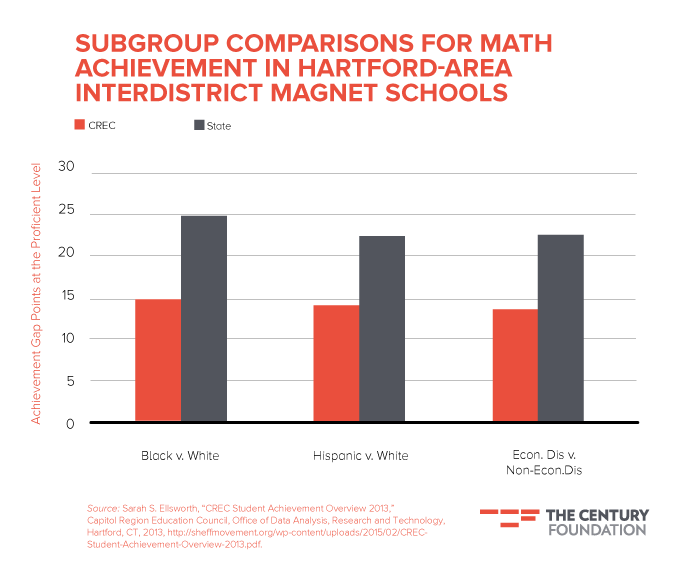

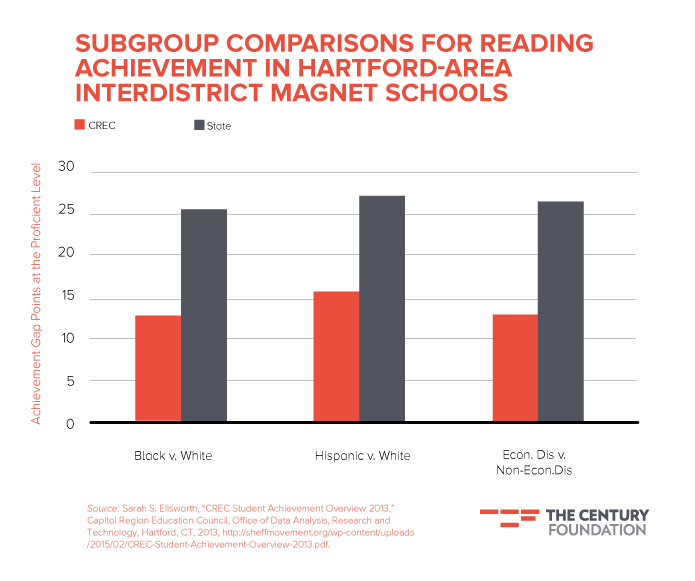

We see this in a local context in Hartford, Connecticut, where racially diverse interdistrict magnet schools were created by the Capital Region Education Council (CREC) in the greater Hartford area. As Figures 2 and 3 illustrate, these “CREC interdistrict magnet schools,” which draw black and Latino students from the city of Hartford and white students from the suburbs, are closing the achievement gap between students of different racial and ethnic backgrounds. Indeed, 2013 state reading test scores in CREC regional magnet schools showed that the gap between black and white and between Latino and white students was eliminated in the third grade. The same was true between Latino and white students’ scores in fifth grade reading. Additionally, by tenth grade the gap in scores between students from low-income families and other students shrunk to just under 5 percentage points in reading in interdistrict magnet schools, compared to 28 percentage points at the state level. Taken together, the achievement gaps between students of different races in these regional, interdistrict magnet schools are significantly smaller than the state overall.44

Figure 2.

Figure 3.

While there are a handful of studies that challenge the link between school desegregation policy and positive academic outcomes, they represent only a small slice of the literature.45 As we argue below, it is highly likely that any less-than-positive short-term academic outcomes of desegregation reported are related to complex issues of implementation and a lack of attention, particularly in the early years of school desegregation, to students’ overall experiences within schools.

Furthermore, these positive academic outcomes, particularly the closing of the achievement gap, make sense given that integrating schools leads to more equitable access to important resources such as structural facilities, highly qualified teachers, challenging courses, private and public funding, and social and cultural capital.46

Other research has examined academic outcomes of racially segregated and diverse schooling that are closely tied to students’ post-secondary careers and college trajectories. The gap in SAT scores between black and white students is larger in segregated districts, and one study showed that change from complete segregation to complete integration in a district would reduce as much as one quarter of the SAT score disparity.47

For one thing, the educational expectations from school staff and performance of students who attend racially integrated schools are significantly higher than those of staff and students from racially segregated schools.48 This also means that students themselves hold higher educational aspirations than their peers who attend racially segregated schools.49 Further, dropout rates are significantly higher for students in segregated, high-poverty schools.50 During the height of desegregation in the 1970s and 1980s, dropout rates decreased for minority students, and the greatest decline in dropout rates occurred in districts with the greatest reductions in school segregation.51 More recently, the interdistrict magnet programs in Hartford, on average, recorded far higher graduation rates than even some of the more affluent suburban districts in the region. This can be largely connected to an overall improved school climate in racially integrated schools.52 These schools not only have lower levels of violence and social disorder than segregated schools,53 but they are also more likely to have stable staffs composed of highly qualified teachers—the single most important resource for academic achievement.54

Additional Benefits, Including Learning Outcomes and Interracial Understanding for All Students

The findings on the racial achievement gap are particularly notable given that school desegregation policy was too often implemented without much attention to students’ day-to-day experiences within racially mixed schools. There has been no distinction drawn as to how different student outcomes were related to the various ways in which students experienced desegregation in their schools and communities.55 Most early research said nothing about the local context of desegregation or how students’ experiences within racially diverse schools were shaped by the actions and attitudes of educators. Thus, the degree to which all students were treated equally or had teachers with high expectations for them was not a factor, despite the impact of such factors on student achievement data. Further, this early literature failed to calculate the prevalence of segregation within individual schools via tracking, or the extent to which black and white students were exposed to the same curriculum.56 Despite this lack of focus on what happens within diverse schools, the outcome data in K–12—as with higher education—still demonstrates that diverse educational experiences lead to positive learning outcomes and better intergroup relationships. A growing body of research suggests that the benefits of K–12 school diversity indeed flow in all directions—to white and middle-class students as well as to minority and low-income pupils. For instance, we know that diverse classrooms, in which students learn cooperatively alongside those whose perspectives and backgrounds are different from their own, are beneficial to all students, including middle-class white students, because they promote creativity, motivation, deeper learning, critical thinking, and problem-solving skills.57 These skills that students gain from diverse learning environments are in line with what policy-makers say should be among the primary focuses of K–12 education.58 They are also skills that are highly desired by employers.59

In addition, there is a pedagogical value inherent in having multiple vantage points represented in classrooms to help all students think critically about their own views and to develop greater tolerance for different ways of understanding issues. It allows for positive academic outcomes for all students exposed to these diverse viewpoints.60 Much of the research on higher education cited before applies to the elementary and secondary educational context. For instance, evidence on how the persistence of implicit bias toward members of minority racial groups can interfere with the educational process by disrupting cognitive functioning for members of both the majority and minority could certainly apply to elementary and secondary students as well.61 Also, the finding that efforts to increase university campus diversity can significantly reduce implicit bias and its detrimental effects would no doubt apply to K–12 schools and would carry over to apply to students experiences in higher education.62

Similarly, since white students in particular have been shown to benefit from racially and ethnically diverse learning contexts because the presence of students of color stimulates an increase in the complexity with which white students approach a given issue through the inclusion of different and divergent perspectives, this would most likely hold true if tested in a high school, discussion-based classroom. In short, the better overall learning outcomes that take place in diverse classrooms—for example, critical thinking, perspective-taking—would no doubt apply in high schools as well.63 If Phillips is right in her conclusion64 that diversity makes us smarter, why wouldn’t it also make us smarter earlier, starting in elementary school and certainly in high school as well?

In fact, in a prior era of American history, when hundreds of school districts were implementing school desegregation policies, there had been a focus, albeit small, on “intergroup contact” in K–12 public schools. It showed that while racial segregation and isolation can perpetuate racial fear, prejudice, and stereotypes, intergroup contact and critical cross-racial dialogue can help to ameliorate these problems.65 More recently, attention has pointed to the role that diverse schools play in preparing students to live in a multicultural society—particularly in terms of promoting interracial understanding and comfort, friendship building, and fostering civic and democratic engagement.66 Further, a longitudinal study on the link between K–12 and post-secondary exposure to diverse learning environments showed that the positive relationship between diversity in higher education and outcomes related to satisfaction, well-being, and racial attitudes are stronger among students who had already had more experiences with diverse learning environments before college.67

This suggests a strong and powerful link between K–12 and higher education experiences when it comes to students’ educational benefits of attending diverse schools. Still, as with the higher education research, we need to more fully explore not only the what of K–12 school diversity, but also the how—how do elementary and secondary school educators create classrooms that facilitate the development of these educational benefits of diversity for all students? To answer this critical question, we need to look at yet another body of K–12 research from the desegregation era and beyond.

How Public Schools Can Help Foster the Educational Benefit of Diversity

Perhaps the ultimate irony of the current lack of focus on the educational benefits of diversity within racially and ethnically diverse public schools is that prior to the rise of the accountability movement in K–12 education, there had been an intentional focus on multicultural education that explored curricular improvements and teaching issues within racially diverse schools. Much like higher education’s shift in focus from questions of “why” to “how” university faculty can foster the educational benefits of diversity within racially and ethnically diverse classrooms, the K–12 research on school desegregation had also started to shift focus from student outcomes to exploring within-school segregation and the curriculum and teaching issues related to racially and ethnically diverse schools.68 It was trying to understand the “how” as well.

Intergroup Relations

Indeed, by the late 1970s and early 1980s, a small cadre of researchers was going inside of schools and trying to understand the “how and why” aspects of student experiences in desegregated schools. Much of this work focused on how students interacted across racial and ethnic groups—what is commonly called “intergroup” relations—and was conducted primarily by sociologists, social psychologists, and anthropologists. They raised important issues about how school desegregation policies should be implemented to create successful desegregated schools.69 They also helped to illustrate the so-called second-generation issues of school desegregation; that is, the process of placing African American students in low-level classes separated from their white peers. This research was also methodologically distinct—consisting mainly of qualitative, in-depth case studies that focused on the process of school desegregation and the context in which it unfolded.70

Through looking at students’ intergroup relations and how educators could create conditions that would foster intergroup understanding, the research stressed the importance of the equalization of academic status between students across racial groups in a manner that enabled students to learn from each other and thus experience the educational benefits of diversity.71

Perhaps the most prolific of the researchers on intergroup relations was Elizabeth Cohen,72 who examined the experiences of students within desegregated schools and how educators could create learning conditions that would foster intergroup understanding and an equalization of academic status (often otherwise correlated with racial background). Like the most recent work in higher education and efforts to understand “how” to achieve the educational benefits of diversity, Cohen focused on pedagogical practices that enabled students to learn from each other.73 In keeping with the need for a more contextual approach to studying school desegregation, Cohen wrote:

The more I have studied the desegregated situation, the more I have come to understand that what happens to children inside a particular desegregated school is a product of changing socio-historical forces which brought that particular school to the “desegregated” state, a product of the status and power relations of minority to majority in the society and community, as well as a product of social and structural forces within the school.74

Understanding these status and power relations outside of schools and how they permeated the classroom walls was central to Cohen’s efforts to construct learning experiences for students in which these external forces of differential status were minimized as much as possible. Psychologist Gordon Allport long ago described a “contact hypothesis” in his 1954 book The Nature of Prejudice, in which he argued that racial and other forms of prejudice can be reduced through equal-status contact of members of one or more racial/ethnic groups in the pursuit of common goals.75 The “equal-status” and “common goals” aspect of this hypothesis are central to the sort of intergroup contact that can facilitate fundamental changes in the way students make sense of each other and question stereotypes they may have heard from adults and peers. Public schools, therefore, are the natural setting in which such contact can occur. Few other institutions have the potential to bring students together across racial, ethnic, and social class lines to facilitate active learning to reduce prejudice. Much of this later school desegregation research helped to illustrate many of the problems associated with implementing school desegregation, including within-school “resegregation” via tracking and grouping. It highlighted very complex issues related to teachers’ attitudes and beliefs about the ability of black students to succeed, as well as their willingness to talk about race as a salient issue within their schools and classrooms. There was a need to illustrate this complexity of desegregation and teaching in racially diverse classes, the day-to-day experiences of students in racially mixed schools, and a greater focus on the “sociocultural” dimensions of schooling as students are coming together across racial/ethnic lines, often for the first time. Teachers were found to have inconsistent views about African American students’ potential to learn and conform to the dominant school culture.76 In another study of a desegregated middle school, it was actually taboo for faculty or students to talk about race, as if it did not shape the daily experiences of students.77

Other intergroup relations studies focused more on the psychological impact of school desegregation on students, particularly African American students. They tend to be inconclusive, because they imply a relationship between the particular conditions established within racially mixed schools and the ways in which children come to see themselves vis-a-vis students of other racial groups.78 Like the research on student achievement, studies examining students’ self-esteem and/or racial attitudes suffered from the same central problem; They generally lacked contextual data to help explain how different students were experiencing school desegregation in different schools and how that influenced the way in which they understood themselves and others. Tracking and ability grouping in desegregated schools often perpetuated within-school segregation across race and class lines. Again, identified as second-generation desegregation issues, this was starting to be addressed in schools across the country and drawing more attention from researchers by the 1990s and early 2000s. In examining the impact of tracking within racially diverse schools, qualitative researchers emphasized the importance of social and cultural factors such as how teachers perceived students’ academic ability, who was considered popular or good looking, and whose perspective, background, and experiences were most valued in classroom discussions. Despite educators’ pronouncements to be “colorblind” and to treat all students equally, differential treatment according to race was the norm, even when different-race students had the same prior achievement and social-class backgrounds.79 Today we call such differential treatment by educators or police officers “implicit bias.”80

Woven throughout this within-school segregation/desegregation literature was a deepening emphasis on the critical need for racially diverse schools and classrooms to address sociocultural issues related to whose knowledge, understanding, and meaning is valued in academic settings. Overall, there had been a lack of attention paid in older “outcomes-focused” desegregation research to what happened inside of schools and classrooms, especially as it related to the dignity of students of color.81 Interestingly, insights and deeper understandings of how to create meaningful and more equal intergroup relations within racially diverse public schools were being written at the same time as the jurisprudence related to school desegregation was being reversed, and levels of racial segregation within schools and whole school districts were increasing.82 While this particular literature did include many appropriate and well-placed criticisms of what was and was not happening pedagogically within these racially and ethnically diverse classrooms, it did not offer many suggestions regarding the appropriate pedagogy for these classes. That came from yet another body of related work in the area of multicultural education.

Multicultural Education and Culturally Relevant Pedagogy: The Curriculum and Teaching Strand of Successful Diverse Schools

As sociologists and others were examining the structural issues of resegregation within racially diverse schools and trying to understand their impact on intergroup relations and students’ sense of marginalization in the 1980s and 1990s in particular, other researchers and educators were coming up with instructional strategies and curricula to address the sociocultural issues discussed above. Much of it falls under the broad umbrella of “multicultural education” and echoes the calls within the higher education literature for more focus on the “how” of the educational benefits of diversity in higher education.83

Perhaps the broadest definition of multicultural education comes from one of the best-known authors in this area, James Banks, who argued that its central goal is to “help all students to acquire the knowledge, attitudes, and skills needed to function effectively in a pluralistic democratic society and to interact, negotiate, and communicate with peoples from diverse groups in order to create a civic and moral community that works for the common good.”84

Framed around the changing demographics of this country and the backdrop of policies such as school desegregation that created more racially and culturally diverse schools and classrooms with a complex cultural make up, multicultural education was attuned to a wide range of issues, including the cultural orientations of students’ families and issues of linguistics. Broadly defined as a research agenda “to unpack the cultural variable” so that differentiating characteristics within cultures could be understood by educators teaching diverse groups of students,85 multicultural education and the exploration of cultural issues in schools analyzed students’ culture in terms of its variable influence on individuals, in contrast to approaches which assign an equal value to culture for all members of a group.“86 This kind of finer-grained analysis of cultural and community life allows educators to more clearly recognize the daily cultural life of the individual child and how it relates to their understanding of history, literature, science, and even math.”87

At the same time that multicultural education was emphasizing this “finer-grained analysis” of the cultural lives of individual students, it was also linked conceptually to an emphasis within curriculum and teaching on the societal implications of culturally diverse nations, with racially and ethnically diverse schools often seen as microcosms of that nation. These cultural issues connected more tightly to a look at the process of preparing teachers—particularly white teachers—to work in racially diverse schools as part of a larger effort to encourage white Americans to reconsider their “whiteness.”88 Pedagogical issues around cultural diversity in schools and classrooms also connect to issues of democracy and democratic learning.89 This multicultural education literature, itself an important body of work in K–12 education—echoed in the higher education literature cited above—on the democratic goals of education and how they relate to racial and ethnic diversity. Critical work on the democratic goals of education echoes not only the concept of multicultural education, but also issues of democracy and pedagogy on racially diverse college campuses.90 Indeed, there is a crucial connection between the discussion of controversial political issues among people with disparate views and the health of our democracy.91 Supporting the growing body of evidence on the educational benefits of diverse classrooms, researchers have found pedagogical value inherent in having multiple vantage points represented in classrooms, helping all students think critically about their own views and develop greater tolerance for different ways of understanding issues. Research documents positive academic outcomes for students exposed to these diverse viewpoints.92

Culturally Relevant Pedagogy

Meanwhile, multicultural education, much like the more qualitative research on desegregated schools and within-school segregation, has garnered less attention in recent years, as the larger policy context has shifted its gaze away from issues of racial and ethnic diversity toward accountability and narrowly defined student outcomes.93 Still, a newer area of research and scholarship that is related to, and to some extent rooted in, multicultural education has grown. Sometimes referred to as Culturally Relevant Pedagogy and sometimes as Culturally Respondent Pedagogy—or just CRP—it also considers how students’ home culture relates to their educational experiences in classrooms, maintaining that teachers need to be nonjudgmental and inclusive of the cultural backgrounds of all their students in order to be effective educators.94

Building on the groundwork of multicultural education research, CRP has also remained focused on the intersection between school and home-community cultures and how that intersection relates to the delivery of instruction in schools.95 But CRP has been more directly applied to the teaching and learning of African American students in contexts that are racially and ethnically homogeneous as opposed to diverse schools and classrooms. While CRP does focus on the importance of culture in schooling, it always focuses directly on race, in part, perhaps, because it is so often adapted in all-black, one-race schools and classrooms.

Another critique of CRP is that its more recent application is far from what was theorized early at its inception.96 Specifically, the superficial, decontextualized, and fragmented application of CRP—and multicultural education—has sometimes resulted in the marginalization of Asian American students due to their limited inclusion in curricular content.97 This is made worse by teachers who have had little training in culturally relevant pedagogy or content and therefore “reinforce a tokenized perspective of ‘minorities’ in this country through an emphasis on celebrations, contributions, food, and heroes.”98

There are thus new linkages developing between CRP and a broader understanding of how culture and race interact in the educational system.99 Multicultural education, and pedagogies that have evolved from it, have the potential to advance desegregation and racial/ethnic equality because, when they can address many of the social and cultural aspects of racially/ethnically diverse classrooms that previous noncurricular reforms have failed to tackle.100 There is much potential for a culturally relevant approach to help all students in racially and ethnically diverse public schools learn from each other in a manner that challenges their own assumptions and indeed makes them “smarter,” more creative, and more thoughtful.

In fact, some scholars have advocated for different pedagogical models since the inception of CRP that seek to address social and cultural factors in classrooms. Many of these models focus on the home-to-school connection as CRP does, while others expand on the application of even earlier concepts of critical pedagogy aimed at promoting concepts such as civic consciousness and identity formation.101 Furthermore, the concepts found in CRP and multicultural education can apply to specific content areas or contexts; for example, the importance of transitioning to reality pedagogy in urban science education when teaching students of color “that begins with student realities and functions to utilize the tools derived from an understanding of these realities to teach science.”102

Most recently, a reflection on the misuse of CRP has called for the rethinking of original theory and welcomes a shift to the theory of Culturally Sustaining Pedagogy, which aims to foster cultural pluralism as part of the goals of a democratic society.103 According to pedagogical theorist Gloria Ladson-Billings, culturally relevant pedagogy should include the multiplicities of identities and cultures that help formulate today’s youth culture. “Rather than focus singularly on one racial or ethnic group,” she writes, Culturally Sustaining Pedagogy “pushes us to consider the global identities that are emerging in the arts, literature, music, athletics, and film.”104

Clearly, there is much rich information, conceptualization, and understanding in the K–12 literature on teaching and learning as it relates to issues of race and ethnicity more broadly. The next step in utilizing these more culturally based understandings of schools and curricula is to apply this thinking to diverse schools and classrooms more specifically. Educators in schools across the country—some isolated in single classrooms and some working on a school-wide set of pedagogical reforms—are starting to grapple with these issues in racially and ethnically diverse classrooms. Some of these efforts are documented in studies of the de-tracking movement and the work on civics education noted above, but far more research on the “how” dimensions of these pedagogical efforts is needed.105

Demographic, Educational, and Political Forces Fostering the Benefits of Diversity within the K–12 Educational System

The fact that the educational benefits of racially and ethnically diverse campuses and classrooms has been a more central argument and defining theme of higher education jurisprudence, leadership, and research than it has in the area of K–12 research and policy is problematic, given the added attention generally to issues of teaching and learning in the K–12 literature. But as we highlight in Figure 1, there are several reasons why issues related to the educational benefits of diversity appear to have fallen off the K–12 research radar screen in the last twenty-five years. This includes, most notably, a highly fragmented and segregated K–12 educational system of entrenched between-district segregation that cannot be easily addressed after Milliken v. Bradley. Meanwhile, this fragmented and segregated educational system is governed by accountability and legal mandates that give no credence to the educational benefits of learning in diverse contexts. As noted above, several areas of research on the sociocultural issues related to teaching students of different racial and ethnic backgrounds that could help inform our understanding of the pedagogical approaches that foster educational benefits of diversity in the K–12 system are disconnected, often designed to address the needs of students in the racially segregated school system they attend.

Still, despite the many factors working against efforts to embrace and develop a parallel “educational benefits of diversity” argument in K–12 education, there are several counter forces influencing the public educational system that could eventually foster a movement to embrace this argument. In this section, we highlight the demographic, educational, and political forces that we think may have the potential to shift the system in that direction.

Demographic Forces: The Changing Population and Metro Migrations

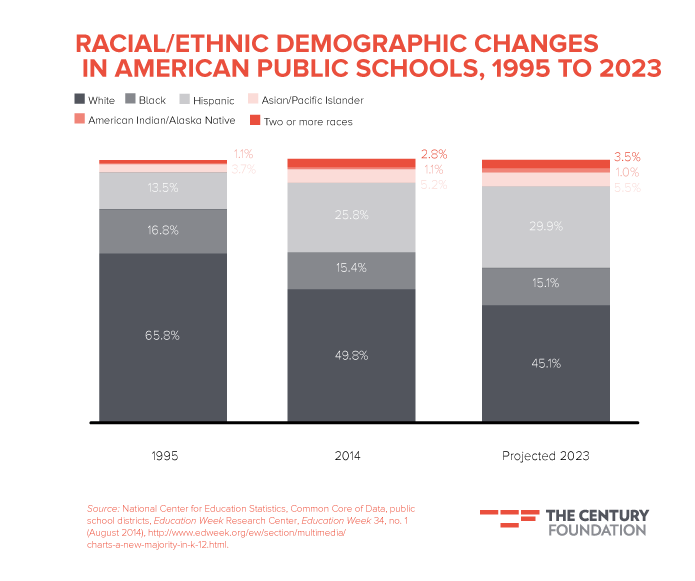

Much attention has been paid to the fact that the U.S. population overall is becoming more racially and ethnically diverse (see Figure 4). The media have pointed out repeatedly that by the middle of the twenty-first century, this country’s population overall will no longer be majority white, non-Hispanic. Even more notably, this transition is happening much more quickly amid our younger population. As of September 2014, for the first time in our nation’s history, white, non-Hispanic students no longer constitute a majority of the overall public school enrollment, according to the U.S. Department of Education. Rapid growth in the Hispanic and Asian populations, coupled with a black population that has remained constant and a decline in the percentage of whites, has led to a total K–12 enrollment of 49 percent white, 26 percent Hispanic, 15 percent black; and 5 percent Asian for the 2014–15 school year.106

Figure 4.

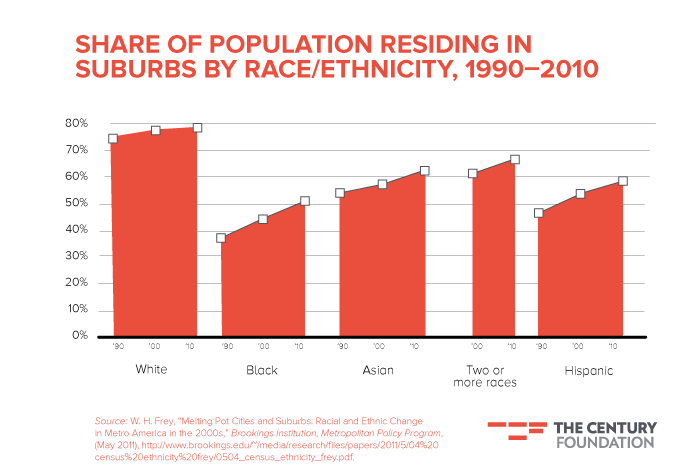

Coinciding with the changing racial makeup of the country and our public schools is a profound shift in who lives where. In many contexts, our post-World War II paradigm of all-white suburbs and cities as the places where blacks and Hispanics live has been turned on its head. For instance, we know that after World War II the government subsidized a movement of millions of white, middle-class families to the suburbs, and many cities became predominantly black and/or Latino.107 By 1980, 67 percent of blacks and 50 percent of Latinos, but only 24 percent of whites, lived in these city centers.108 At that time, only 23 percent of blacks lived in the suburbs. Black suburbanization rates were even lower—about 12–15 percent—in the Northeast.109

But these racialized housing patterns are in the midst of another epic shift. For the last twenty-five years, the first and second-ring suburbs of major cities have been at the forefront of the reversal of “white flight” from cities to suburbs. Beginning slowly in the 1980s and increasing in the 1990s and 2000s, when federal policies and regulations (or lack thereof) promoted home ownership among moderate-income families,110 growing numbers of black, Latino, and Asian families were moving to suburbs such as Ferguson, Missouri (see Figure 5). By 2000, nearly 40 percent of blacks were living in the suburbs. Suburbanization has also increased among immigrant families—mostly Latino and Asian—and by 2000, 48 percent of immigrants were residing in suburban areas.111

Figure 5.

In the 1990s, journalists and researchers were increasingly reporting on the growing number of distressed suburbs that were coming to resemble poor inner-city communities. For instance, from 1990 to 2000, while some newly developing suburbs experienced rapid growth in people and jobs, “many older suburbs experienced central-city-like challenges, including an aging infrastructure, inadequate housing stock, deteriorating schools and commercial corridors—and population decline.”112 In 2000, while suburbs were still more affluent than cities on average, certain cities were becoming less poor and their residents were more educated than their suburban counterparts.113 By 2008, an Atlantic Monthly article highlighted the impact of the sub-prime mortgage crisis on suburban communities experiencing high rates of foreclosures. But the author was quick to note that declining suburban neighborhoods did not begin with the mortgage crisis, and they would not end with it as more people with high incomes move into the cities.114

This leads to what is conceptualized in the current, post-2000 era, as the still- evolving period of metro migrations, which we refer to as “trading places,” with affluent whites moving back into cities and lower-income people of color moving to the suburbs—either by choice or via displacement in gentrifying city neighborhoods.115 This pattern has continued in the last decade, as black and recent-immigrant suburbanization has continued, and a growing number of upper-middle-class and relatively more affluent whites are moving back into urban centers.116

Lured by the convenience, excitement, and culture of city living, increasing numbers of highly skilled whites in so-called “global cities” such as New York and San Francisco have opted out of long daily commutes by living in nearby urban, and often gentrified, neighborhoods.117 City life, once considered by many whites as dangerous, dirty, and crowded, is now increasingly associated with excitement, fun, and convenience.118 Indeed, a recent poll found that 77 percent of Millennials expressed a preference for urban life.119 In her recent book, The End of the Suburbs, Leigh Gallagher of Fortune magazine notes that 2011 was the first year in decades that population growth in the cities outpaced that of the suburbs, and home builders now say their best markets are the urban, gentrifying neighborhoods.120 Cities and suburbs have experienced a “demographic inversion” as a result of their changing racial composition.121

The New York City metropolitan area represents a prime example of the most recent trading spaces phenomenon. The percentage of whites in Manhattan increased 28 percent between 2000 and 2006, while it declined in nearby suburban Nassau County. During the same six-year period, the Hispanic population declined by 2 percent in Manhattan, but increased by 20 percent in Nassau. This twenty-first century urban aristocracy—or “gentry”—is driving up home prices in select city neighborhoods, sometimes pushing lower-income residents—mostly black and Latino—into outlying urban and inner-ring suburban communities.122

Meanwhile, a growing number of American suburbs where more than half of the U.S. population—about 53 percent—still lives are increasingly diverse in terms of race, ethnicity, and culture, giving the suburbs a far more cosmopolitan feel than in the post-World War II era. In fact, today, in the fifty-largest metropolitan areas, 44 percent of residents live in racially and ethnically diverse suburbs, defined as between 20 and 60 percent non-white.123

Overall, these fluctuating metropolitan characteristics suggest that traditional paradigms of “cities” versus “suburbs” are rapidly evolving in ways that we cannot yet completely comprehend. Indeed, it is increasingly clear that contemporary urban and suburban communities each contain pockets of both poverty and affluence, often functioning as racially and ethnically distinct spaces. In fact, by 2005, one million more poor people lived in suburban compared to urban areas.124 While the rate of demographic change differs by context as well, there are moments of “de facto” racial/ethnic diversity in our cities and suburbs that are affecting more than just neighborhoods.

Urban and Suburban Public Schools amid Demographic Changes

This demographic “trading places” phenomenon, or the “great inversion,”125 has many implications not just for housing patterns and property values, but also the public schools in these transitioning communities. In Brooklyn, New York, for instance, a growing number of communities that were, only ten years ago, almost entirely minority and low-income are now becoming (or have already become) predominantly white and affluent. The families who had sent their children to the public schools in these communities for years are now being “displaced” from their neighborhoods and their public schools. Ironically, in in-depth interviews we are conducting, white gentrifiers state that one reason they moved into the city was to live in neighborhoods more diverse than the homogeneous suburbs where many grew up. Similarly, they note that they want their children to attend public schools with other children of different backgrounds.

Thus, while much of the focus of anti-displacement has been on housing policy, too little attention has been paid to school policies that affect who is being “displaced”—physically and academically—from schools as well. There is much hard work to be done at the school level to assure that all students enrolled have the opportunity to achieve to high levels. In public schools with a growing population of more affluent students, educators often seek assistance in meeting the needs of a wide range of students.

In the last decade, a small but growing body of literature has documented the impact of urban gentrification on the enrollment and culture in public schools.126 Still, most of it examines the gentrification process and its impact on public schools through the eyes of white, middle-, or upper-middle-class parents, and rarely does it examine deep pedagogical issues in schools related to a changing student body in which issues of race, class, power, and privilege are being lived, if not explored, in the classrooms.

There is also an emerging focus on the impact of changing demographics on suburban public schools.127 In our research on Long Island, for example, we studied inner-ring suburban schools that shifted demographically from having a more than 90 percent white, non-Hispanic student body in the 1990s to only 15 percent white, non-Hispanic by 2014. In other suburbs, further from the New York City boundary, the white, non-Hispanic population has stabilized at about 50 percent. In both contexts, educators and students are grappling with racial, ethnic, and cultural differences that many of them had not encountered before.

When we think of education policies and practices to support and sustain the increasingly diverse public schools in both urban and suburban contexts, it is clear that K–12 educators and educational researchers have much to learn from the higher education research on the educational benefits of diversity in efforts to both close racial and socioeconomic achievement gaps while helping all students succeed. And just as fair-housing advocacy has increasingly prioritized the stabilization and sustainability of diverse communities, education policy needs to follow suit. Unfortunately, too few policy makers see the need for such programs, even as a growing number of educators in diverse schools are clamoring for help to close those gaps and teach diverse groups of students.

The current mismatch between the policies and the needs of an increasingly racially and ethnically diverse society inspire us to fill the void with compelling success stories of public schools working toward a greater public good by tapping into the possibility of changing neighborhoods to teach children how to thrive in a society of racial and cultural differences. One of the schools we are studying in a gentrifying area is helping build more cross-racial understanding across the Hispanic and white parent groups by trying to assure more equal voice in the decision-making processes—everything from the kind of food and music available at the fund raisers to the mix of various field trips to cultural institutions. Another school, in a suburban school district, is trying to develop a new set of elementary school attendance zones, and/or moving toward a mini-controlled choice model to avoid the segregation of the growing Hispanic student population into one elementary school.

Schools and communities on the front lines of demographic change face significant obstacles to realizing the sort of educational benefits of diversity that can help us all understand and appreciate differences. Urban history suggests that when a racial group begins migrating to a new community, the existing population is likely either to be pushed out or to flee, setting into play a perpetual cycle of segregation and resegregation. At the heart of these cycles are public schools with educators who are rarely prepared to facilitate the “educational benefits” of a diverse student body—a concept supported by the higher education research and the federal courts.

Even in the most unstable and rapidly changing contexts, there are moments of “de facto school diversity” within demographically changing neighborhoods.128 In these spaces, higher education research on the educational benefits of diversity could be extremely helpful to assist educators in garnering the academic benefits of diverse schools and classrooms to help prepare all students for the twenty-first century. The most disadvantaged students are the most negatively impacted by such a failure.

Political Forces in Favor of More Racially and Ethnically Diverse Schools and Their Educational Benefits

As we noted above, the current policy context of K–12 education has dramatically shifted the focus away from issues of racially and ethnically diverse schools—both in terms of how to create them through race-conscious student assignment/school choice and in terms of teaching and learning within diverse schools.129 At the same time, however, mounting evidence suggests that accountability and school choice policies, premised on narrow definitions of school quality and absent interventions to support diversity, exacerbate racial and social-class segregation and inequality.130

Thus, as leaders in higher education have relied heavily on social science evidence to put forth a powerful legal and policy argument in support of the educational benefits of diverse campuses and classrooms, the policy priorities in K–12 public education have gone in the other direction, with a strong focus on narrow accountability measures within increasingly segregated schools. This K–12 policy emphasis is not only out of line with higher education’s priorities, but it is also extremely shortsighted and problematic given the demographic changes among younger generations, and the growing demand from both universities and employers for high school graduates with experiences in diverse contexts and the ability to cross cultural boundaries.

In this last section, we provide an overview of two key political forces—changing racial attitudes and the backlash against standardized tests as the central measure of “good” schools—that support a return in K–12 education policy focus to the issue of racial and ethnic diversity.

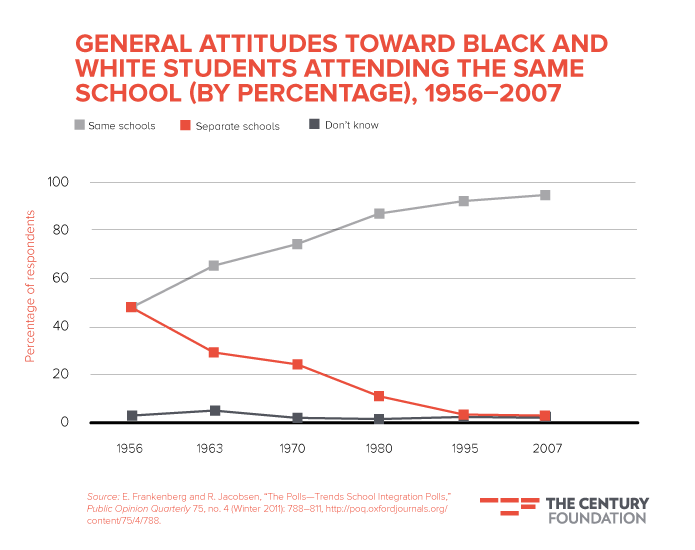

The Growing Demographic Diversity Reflected in Attitudes