After the October 2017 fall of Raqqa to U.S.-backed Kurdish and Arab guerrillas, the extremist group known as the Islamic State is finally crumbling. But victory came a cost: Raqqa lies in ruins, and so does much of northern Syria.1

At least one of the tools for reconstruction is within reach. An hour and a half’s drive from Raqqa lies one of the largest and most modern cement plants in the entire Middle East, opened less than a year before the war by the multinational construction giant LafargeHolcim. If production were to be resumed, the factory would be perfectly positioned to help rebuild bombed-out cities like Raqqa and Aleppo.

However, although the factory may well hold one of the keys to Syria’s future, it also has an unseemly past.

In December 2017, French prosecutors charged LafargeHolcim’s former CEO with terrorism financing, having learned that its forerunner Lafarge2 was reported to have paid millions of dollars to Syrian armed groups, including the terrorist-designated Islamic State.3

The strange story of how the world’s most hated extremist group allegedly ended up receiving payments from the world’s largest cement company is worth a closer look, not just for what it tells us about the way money fuels conflict, but also for what it can teach us about Syria’s war economy—a vast ecosystem of illicit profiteering, where the worst of enemies are also partners in business.

This work was supported, in part, by a research grant from The Harry Frank Guggenheim Foundation, and by the Carnegie Corporation of New York. It draws on interviews with Syrian and international experts, diplomats, fighters, and people involved with Lafarge’s operations in Syria, as well as on a wide range of written sources in English, Arabic, French, and Norwegian, including press coverage, company reports, memoirs, and social media.

Lafarge’s behavior, which is now under investigation in France and could result in criminal convictions, was far from exceptional for companies operating in civil-war Syria—or perhaps in any similar war zone.4 The need to consider opportunistic compromises, dubious deals, and under-the-table payoffs to criminal and violent actors to keep Lafarge’s factory in operation will therefore also be difficult to avoid for others hoping to operate in Syria’s fragmented politico-economic landscape.

The fact that President Bashar al-Assad’s government is now clearly dominant and the Syrian war seem to be moving toward a reconstruction stage will only exacerbate the problem.5 The fighting is far from over and the country remains divided, with rival armed actors ruling several peripheral areas. The most important one is the northern, Kurdish-controlled region propped up by the United States.

As long as these divisions remain in place, many humanitarian and commercial actors will be forced to work under two or more rival regimes, negotiating a path among militant actors who routinely prey on industry, trade, and relief operations. During the war, a new class of conflict traders has emerged to facilitate cross-line connections of this type. Though they hail from different backgrounds and areas, most retain strong links to Assad’s government. As reconstruction money starts pouring in, it will be near-impossible to avoid some level of dependence on these regime-connected fixers and war profiteers—the new kings of Syria’s economy, whose power grows as the Syrian army advances.

Corruption in Syria before 2011

Doing business in Syria was never a good way to keep your hands clean. The half-century-old regime of President Hafez al-Assad, who took power in 1970, and his son Bashar, who succeeded him in 2000, has gained a well-deserved reputation not only for authoritarianism, but also for graft and greed.6

One of the ways in which members of the ruling elite skimmed money from private enterprise was by attaching themselves to wealthy investors. Foreign companies looking to enter the Syrian market were obligated to work with a local partner, often in the form of some regime-friendly oligarch or military surrogate whose main contribution to business would be to grease the most relevant palms and show teeth to rival predators.

Some of these figures mirrored the president’s own trajectory by inheriting power, as sons of aging Baath Party apparatchiks or senior officers. Syrians referred to these men with equal parts fear and disgust as awlad al-sulta, “the sons of power.”7

The most infamous example was the president’s cousin Rami Makhlouf. Relying on an endless parade of brothers, cousins, and friends in government, Makhlouf had become notorious for using the muscles of the police state to block legitimate competition. Though Makhlouf has “long been Syria’s poster-boy for corruption,” he had also grown fabulously wealthy, with a business empire that “spanned nearly all sectors of the Syrian economy by 2005.” Many viewed the meteoric rise of regime insiders like Makhlouf as something more than just uncontrolled graft—it was, they felt, the ruling elite’s way of coping with economic reform, by making sure that the means of production would stay in the family whether state-run or privately owned.8

“The sons of the rulers are transforming into monied tyrants,” said the leftist former political prisoner Riad al-Turk, who, lowering his voice at the Damascus cafeteria where I met him in 2008, insisted to me that Assad’s push for economic liberalization was merely a way to drop public assets into the pockets of his friends and relatives. “They monopolize the economy rather than the government, but through the economy they then seize the government. In the past, they used to monopolize the government and exploit it to get rich—in the name of socialism, they plundered the public sector. The form changes, but the content stays the same.”9

The Factory

It was into this economy that the French cement giant Lafarge waded in December 2007, by acquiring its Egyptian competitor Orascom Cement at the eyebrow-raising price of $12.8 billion.10 It was a bold move, and since the global economic crisis struck immediately after, many wondered whether the affair had perhaps been a terrible error—but Lafarge appeared determined to recoup that money and more by breaking into new Middle Eastern markets.

At the top of the list was Syria. Before being bought by Lafarge, Orascom Cement had inked a deal with the Syrian company MAS to build one of the country’s first private cement factories near the northern city of Raqqa. When Lafarge took over Orascom Cement, they inherited its joint venture with MAS, which would become known as Lafarge Cement Syria (LCS).11

At $680 million, LCS would be responsible for Syria’s largest-ever foreign investment outside the oil sector, representing more than a tenth of the country’s state budget at the time.12 Its production capacity of three million tons per year was vastly higher than any of Syria’s six government-owned cement plants, which, typically for the Baathist state’s bloated and decrepit public sector, only managed to churn out 5.3 million tons combined in 2008—well short of demand.13 In every way, this was a big deal.

The site chosen for the LCS plant, Jalabiyya, gave no hint of the grand plans drawn up for its future. Had the outside world not made its presence felt in the form of traffic roaring along the east-west M4 highway, this would have seemed the middle of nowhere. The closest human settlement was Khorrab Asheq, a miserable little Kurdish hamlet just across the M4, which had about half as many inhabitants as the up to 700 people employed at the factory.

“The area is very isolated,” recalls Jacob Wærness, a Norwegian who worked as a risk manager at the factory between 2011 and 2013. “When you drive east from Manbij and you cross the Euphrates, there’s sort of a pocket of green land. The further east you go, the landscape gets more rugged and barren, at least in the summertime. In the winter you can have a little rain and sometimes even snow. In spring, when things start to grow, there’s a thin green cover of vegetation. There will be herds of sheep grazing in the hills. The factory is in this dry, stony area, dotted with small, mostly Kurdish villages.”14

Formally, Jalabiyya belonged to the Aleppo governorate. In reality, this far-flung spot of grass and rocks shared little with the three-million-strong metropolis to its west. For all practical purposes, Jalabiyya was part of the Jazira, an ethnically mixed rural region of Bedouin Arabs, Kurds, and Syriac Christians that stretches through Syria and Iraq along the Euphrates and Tigris rivers.

Though the Jazira’s oil wells, hydroelectric dams, and wheat fields are pillars of Syria’s economy, the region had always been treated as a backwater by Damascus, giving rise to resentment among locals of all ethnic and religious stripes. “The non-industrialization of the Jazira and the over-concentration of industries in Aleppo was condemned by the Raqqawi intellectuals from the 1990s on,” says Myriam Ababsa, a leading expert on the region with the Institut Français du Proche-Orient.15

The arrival of LCS seemed set to change that—and it fit perfectly into Bashar al-Assad’s vision for how Syria should move away from state socialism and find a new economic footing.

Three years earlier, the Baath Party had inaugurated Syria’s transition to a “social market economy,” empowering Deputy Prime Minister Abdullah Dardari to use the country’s 2006–2010 five-year plan as a battering ram for liberalizing reforms. Dardari’s efforts included breaking a decades-old state monopoly over the cement sector.16

With a nod to the war then raging next door in Iraq, Dardari had proposed public investments in Jazira cities like Raqqa, which he hoped could become a “rear base for Iraq’s reconstruction.”17 Improving ties with Turkey also resulted in growing cross-border commerce, accelerated by a major free trade deal in 2007. As northern Syria readied itself for a construction boom, the future looked bright for business—and there was clearly money to be made in cement.

A Beautiful Friendship

If money was to be made, strings had to be pulled. For that, Lafarge turned to its new local partner, MAS. It seemed a good fit for the role, as one of Syria’s leading conglomerates, with a varied portfolio of interests and an insatiable appetite for expansion.

Very relatedly, it was also the economic vehicle of Firas Tlass.18

An iconic representative of the awlad al-sulta, Firas Tlass was born into a military family from Rastan, near Homs, in 1960. Twelve years and four coups later, his father Mustafa was appointed Syria’s minister of defense, having helped his old friend Hafez al-Assad to seize power in 1970.

Although Mustafa Tlass would be kept in the job for an incredible thirty-two years, his position had become “increasingly ceremonial in nature” already by the late 1970s.19 But even without the political clout to match his gilded titles, Tlass’s decades-long friendship with the president made him untouchable to rivals, never mind to the judiciary. Tales of personal and financial improprieties began to pile up.

To the opposition, Mustafa Tlass represented the worst of Baathist rule: incompetence, corruption, brutality, and a sneering contempt for democracy. “We used weapons to assume power, and we wanted to hold onto it,” the former defense minister smilingly told a German reporter in 2005. “Anyone who wants power will have to take it from us with weapons.”20

Several of Mustafa Tlass’s relatives rose to leading positions in the military, most notably his son Manaf, who became a brigadier general in the Republican Guard.21 But his oldest son, Firas, chose another path—he decided to try his hand at business.

Mid-1980s Syria was no easy place to run a company, but Firas Tlass turned out to have a natural talent for winning public tenders from the Ministry of Defense. Among other things, he landed a monopoly on meat sales to the 300,000-strong Syrian army.22 With such luck, MAS had soon grown into a sprawling conglomerate that worked in manufacturing, food imports, agricultural distribution, coffee roasting, dairy production, canned fruit, real estate, and, for a while, Iraq sanctions busting.23

“As many well-connected Syrian businessmen [did,] he was leveraging his connections to develop his business and enrich himself,” says Jihad Yazigi, who edits The Syria Report, an influential newsletter on Syrian economic affairs. Tlass was not particularly close to Rami Makhlouf and he tried to polish his image by sponsoring civil society projects and appearing as a patron of the arts, Yazigi says, but it was clear that “he owed all his wealth to who his father was.”24

Having someone like Firas Tlass on the board of LCS meant that the Syrian government would rally behind the company, seeing that one of its own had put money down for its success.

France, too, quickly swung behind the project. After years of isolation and conflict over Lebanon and Iraq, the new French president, Nicolas Sarkozy, wanted to reboot his country’s relationship with Syria. On July 14, 2008, he invited Assad to the Bastille Day parade in Paris, shattering the Syrian president’s status as a pariah in the West.25 Assad did not fail to repay the favor, and when Sarkozy arrived in Damascus a few months later he was rewarded with three deals for the French oil company Total.26

By 2010, the newly appointed French ambassador in Damascus, Eric Chevallier, could be seen feting LCS at a Four Seasons celebratory dinner.27 For that year’s Bastille Day celebrations, Firas Tlass invited Syria’s rich and beautiful to a gala event in the ancient citadel of Damascus where Syrians and French expats mingled in T-shirts reading “I Love Damascus” and “I Love Paris.”28

Production Starts

Some 400 kilometers north, the Jalabiyya factory had grown into an imposing complex of silos, towers, masts, and conveyor belts, its highest structures looming 130 meters high over the flat countryside. Four kilometers of concrete walls surrounded the site, and LCS had even brought in Chinese contractors to build and operate its very own coal-fueled power plant.

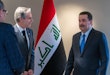

The Jalabiyya factory began to churn out cement in May 2010.29 It was a big event for all involved, and reporters were invited to tour the facility in the company of Lafarge CEO Bruno Lafont, Firas Tlass of MAS, and French Ambassador Eric Chevallier—the trinity of private capital, Syrian elite involvement, and official French backing that had made the Jalabiyya factory possible and profitable.30

Cement sales worked according to a business principle called “ex works,” meaning that LCS simply made pre-packaged cement available for pickup at the Jalabiyya warehouses, while assuming no responsibility for transports, onward distribution, or future sales. Customers would collect the product using their own drivers and cars. The top buyers were construction companies with distribution networks that could span several cities, though the factory also sold to small, independent customers.

In other words, traffic along the M4 could be very heavy. When operating at full speed, the plant would spit out enough cement to fill 160 large trucks each day, an amount that would weigh in at 8,000 tons and sell for about $500,000. Jalabiyya drew buyers from all over northern Syria, and fifty-kilo cement bags bearing the Lafarge logo could soon be found on the market in Manbij, Aleppo, Hassakeh, Qamishli, Kobane, Raqqa, and occasionally even further afield.31

Yet the factory had achieved surprisingly little for the locals. A few families in Khorrab Asheq had sold land to LCS, but the factory only hired a small number of villagers as guards or cleaners, or in other unskilled jobs. Reflecting both its need for educated staff and the origins of the company, LCS had a management structure dominated by Egyptians and Syrians from large cities in the western and central parts of the country, while local employees mostly hailed from Arab-majority Raqqa, Manbij, or Ein Eissa.32

The fact that most LCS employees were Arabs from larger cities in an area dominated by poor Kurdish villagers tied into the ethnic tension simmering across northern Syria. Since coming to power in 1963, the Baath Party had enforced a ban on the Kurdish language and culture, refused to grant citizenship to many Kurds, aggressively favored Arabs in mixed areas, and jailed anyone who protested.33 Unsurprisingly, many Syrian Kurds were profoundly alienated from their government and had drifted towards Kurdish nationalism, represented by a number of rival clandestine political parties. Few paid their low-level agitation any heed at the time, but very soon they would.34

Descent into Conflict

Barely had the LCS plant opened before things fell apart. In March 2011, protests against the Assad family’s four-decade rule erupted in southern Syria. A year later, thousands of people were dead and fighting raged across the country.

In August 2011, the United States and its European allies called on Assad to step aside.35 Spurred on by France and the United Kingdom, the EU imposed “unprecedented” sanctions on Syria, including an oil embargo by autumn 2011.36 Many European companies scaled down their presence in Syria or withdrew entirely, including France’s Total, which suspended operations in Syria in response to the oil sanctions.37

Lafarge chose otherwise. In 2011 and early 2012, LCS had not yet been touched by the unrest that plagued other parts of Syria. The risk of tripping over American or European financial restrictions was a concern, but sanctions did not target the cement business.38 There was no pressure to leave from the Syrian government, which, to the contrary, wanted the factory to stay, being eager to project an air of normalcy and secure continued LCS tax payments.

Bruised by the 2008 financial crisis and with $680 million already spent at Jalabiyya, Lafarge executives were eager to harvest the seeds they had planted in Syria.39 Syria-based LCS executives and staffers also gritted their teeth and said they wanted to push on.40 Even if it was French-owned, LCS was a Syrian company, and local employees feared being shut down—their expat colleagues could leave Syria, but they had nowhere else to turn and these were uncertain times. Along with the usual profit motives, local managers seemed to feel a genuine sense of responsibility for their staff.41

As a compromise of sorts, Lafarge ordered LCS to hire a risk manager, Jacob Wærness, who was sent to Syria to work under the Damascus-based administrative director Marc Castel.

An Arabic-speaking former intelligence officer in his native Norway, Wærness arrived in Syria in September 2011, first renting a house in Damascus and later moving to live at the factory itself. Over the following two years, the Norwegian would spend his days fretting over safety and transport blockages, with other employees only slowly coming around to his pessimistic reading of the situation. Meanwhile, Syria slid into all-out war. It was, Wærness later wrote, like the old parable about how to boil a frog—heat up the water very slowly, and the frog won’t realize what’s happening until it is too weak to jump out of the pot.42

New Powers Emerge

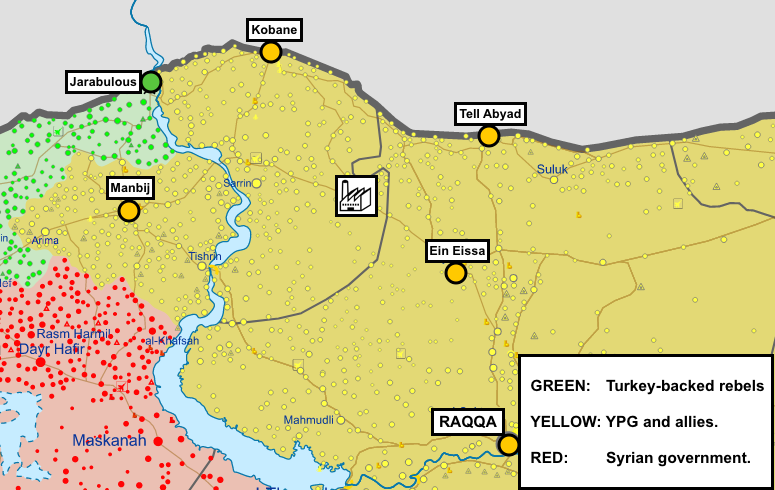

In July 2012, the violence percolating across northern Syria burst into all-out war around Aleppo. Turkish- and Qatari-backed rebels seized the eastern neighborhoods of the city, prompting the Syrian army to withdraw from the mostly Kurdish-populated northeastern hinterland in order to safeguard the major cities.

Wherever the army evacuated Kurdish regions, power fell to the Popular Protection Units (YPG), an ideologically doctrinaire and highly disciplined proxy of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), a left-wing group that has waged war for Kurdish rights in Turkey since the late 1970s. Up until the late 1990s, the PKK had been an ally of Syrian intelligence, but the politico-economic thaw with Turkey in the 2000s prompted a series of harsh crackdowns on PKK sympathizers in Syria.43 Although representatives of PKK-aligned groups denied it, the relationship appears to have been partially reestablished in 2011 in response to Turkey’s anti-Assad turn.44

“From one week to the next, the regime just disappeared from the area around the plant,” recalls Jacob Wærness. “Local police had to hand over their weapons and close their stations, and the Kurds took over. It all happened very smoothly. I don’t think a single bullet was fired.”45

In nearby Arab-majority cities like Manbij, a number of very different groups filled the void. Most hewed to some form of Sunni Muslim identity, mixed with Syrian nationalist themes. Although many referred to themselves as members of the Free Syrian Army—a term loosely associated with state-funded, non-jihadi factions—they lacked a common military hierarchy.

“The Free Syrian Army is a label, so we are the Free Syrian Army, everyone who carries a gun is now called the Free Syrian Army,” said Abdelqader Saleh, a Qatari-sponsored Islamist who, as head of the Tawhid Brigade, was the most powerful rebel figure in northern Syria by mid-2012.46

For lack of effective central leadership and means of coordination, Manbij and other Arab-majority areas slid into a form of anarchy, where numerous small armed factions, revolutionary councils, and sharia courts competed with each other for visibility, recruits, and resources.47 In this chaotic environment, small but disciplined and ideologically stringent jihadi groups found fertile soil for expansion.48

At the time, however, LCS worried more about crime.

With gangs of armed men of uncertain allegiances now roaming the northern countryside, road travel was becoming increasingly dangerous, especially at night. This was a problem for workers at Jalabiyya, who needed to travel back and forth between the factory and their homes, and who had to go to government-held Aleppo to collect salaries paid out through local banks. It was also starting to hurt daily operations. Sales depended on dozens of trucks being able to arrive safely every day to pick up cement, with drivers sometimes carrying very large amounts of cash.

LCS managers were also increasingly worried that Jalabiyya itself could come under attack, since news had spread about opposition fighters looting factories and businesses in Aleppo.

“The assumption has been that if you are a successful businessman in Syria, then chances are that you have been close to the government,” a Syrian businessman told me in 2013. “When the rebels reached the industrial district of Aleppo for example, the attack and stripping of the factories was indiscriminate. To the rebels, the business community and the regime were two faces of the same coin.”49

Paradoxically, these risks only seem to have reinforced Lafarge’s determination to stay in Syria. Had Jalabiyya been abandoned, armed groups would almost certainly have taken over the plant and looted it, and perhaps fought over the spoils. Any hopes of being called upon for post-war reconstruction would then be lost. “They wanted to keep the lights on to protect the property,” concludes Wærness.50

In the latter half of 2012, this did not seem like an impossible task. The YPG was a well-disciplined force whose commanders seemed protective of the factory, and the group was strong enough to keep most rivals at a distance. As long as road travel could be minimized, the situation would perhaps be bearable.

Again, LCS opted for compromise and accommodation, instead of throwing in the towel. Most of the administrative staff in Yaafour, outside Damascus, withdrew to Cairo along with the Egyptian expats, while Wærness and many Syrian workers relocated to Jalabiyya.51 In December 2012, he was told that armed Syrian intelligence officers had visited the offices in Yaafour to look for him. From that point on, he decided not to return to Damascus.52

“Keep Your Enemies Close”

A lone, blonde Norwegian, Jacob Wærness must have seemed madly out of place in the spiraling chaos of northern Syria, but he insists that he felt safe behind the walls of the factory. From his new home at the LCS plant, he launched a program of outreach to the armed groups of the Aleppo-Raqqa region, hoping to quickly figure out who was who, who would be a threat, and who could offer help.

At the top of the list was of course the YPG, which controlled the region around the factory. According to Wærness, after making contact through a Damascus-based associate of Firas Tlass, who appears to have moved swiftly to purchase goodwill, the YPG leaders explained that they wanted the company to stay and continue production; a cement plant would be an excellent addition to their future autonomous region. Even so, local commanders sometimes took matters into their own hands, and the relationship was far from pleasant for LCS and its employees.

“The YPG were the ones who ensured our safety, but they were also the ones who pressured us the hardest,” says Wærness. “They could, for example, make the locals block the access road to the factory, shutting down all our operations. Or they could threaten us, saying that we should know that they guaranteed our safety and that unless we supported them, the factory could come under attack.”53

Local YPG officials would occasionally drop in with demands for support, or find other ways to siphon resources from the factory. On one occasion, things got out of hand and ended in an armed heist, with doors kicked in and guns pointed at employees. “We had twenty or so pick-up trucks on the factory grounds,” Wærness recalls. “The Kurds stole every single one of them. They told us they had better use for them than we did, but if we were willing to talk about it, perhaps they could return a few of the cars. It turned into endless negotiations, and of course we had to pay.”54

Relations with the Arab rebels were normally less intense, since they were farther away and therefore had a weaker hand to play against LCS, but all interactions with the rebels were also more fraught with danger. Unlike the YPG, the Arab militias had no central command that could keep criminal or extremist elements in check, and relations among the local commanders fluctuated unpredictably.

“In Manbij, which was a city of about 100,000 inhabitants, they had perhaps twenty different Free Syrian Army groups in late 2012,” says Wærness. “If you went to a neighboring town, you could encounter a group with the same name but an entirely different leadership. So the Free Syrian Army landscape was—well, very complicated.”55

To make matters worse, according to Wærness, word quickly spread across the region that LCS was paying protection money to the YPG. Some rebels became angry and hostile, since they saw the Kurdish group as an enemy. Others were tempted to reach for a slice of the pie.

Dealing with Kidnappers

LCS suffered its first kidnapping in August 2012, when a group of gunmen abducted a former employee at a café in Manbij, apparently thinking that he was still with the company. The kidnappers claimed to represent the Free Syrian Army and concocted a bizarre story about LCS hosting Iranian snipers. Their real interest was clearly money, and the victim’s relatives eventually paid a ransom.56

Two months later, a van carrying nine LCS employees from the Syrian coast was pulled over on the Raqqa-Kobane road. Several Free Syrian Army-branded groups from the Manbij-Jarablous area took part in the operation.57

“The kidnappers wanted someone released from jail,” recalls Wærness. “We told them we had no influence over that. They also thought one of the hostages was in some way related to the presidential family, which turned out to be wrong.58 But some of the hostages were Alawites, which they saw as being a political thing—or rather, they used it as an argument. But I think in practice, it was really all about money and influence.”59

Although it was not company policy to pay ransoms, LCS decided to make an exception when so many lives were at stake. A deal for 25 million Syrian pounds (€220,000) was reached after mediation by a well-connected Free Syrian Army figure from Manbij, who—as Wærness would later learn to his dismay—had conspired to inflate the amount and ended up absconding with a third of the money to Turkey.60

“The handover of money and hostages took place in the desert in the middle of the night,” remembers Wærness, who drove to the meeting place with a group of rebel bodyguards and 30 kilos of cash stuffed into plastic bags. The kidnappers showed up after a long wait, dressed to impress in black head bands, waving heavy weaponry. “It was a tense situation and there were a lot of armed people there,” Wærness recalls five years later. “But when it came to the purely personal relations, it was—as always in Syria—quite pleasant. I kept a friendly tone in conversation even with the worst kidnappers. We shook hands and made small talk.”61

The situation was strange and dangerous, but it was also part of a new normal. Buffeted on all sides by unpredictable armed groups, LCS staff needed to keep a distance from the insurgency’s byzantine internal rivalries. There was no telling how the war would be configured tomorrow, and in such a fluid state of affairs, the safest bet was to antagonize no one. “Even if I didn’t like what people were doing to us, I had to maintain the relationship,” Wærness says, “because in a place like Syria, you need to keep your enemies close.”62

The Shape-Shifting Mr. Tlass

As he began reaching out to Syria’s rebels in early autumn 2012, Wærness relied heavily on Firas Tlass, who had by then transformed himself from regime tycoon to high-end opposition fixer.

Although the exact circumstances remain murky, both Firas and his brother Manaf started to drift away from Assad’s side in mid-2011.63 Army crackdowns on the family hometown of Rastan seems to have made the dispute bitter and personal, and by late 2011 large numbers of officers from Rastan were making plans to defect.64 Manaf had started to boycott security meetings at his Republican Guard offices in Damascus, and Firas, now rumored to be in bad standing, was dividing his time among Dubai, Paris, and Damascus.65

In July 2012, Manaf Tlass suddenly defected, turning up with his family in Paris, where his father and other family members already resided.66 Firas Tlass then announced that he had supported the uprising all along and would now use his fortune to fund the insurgency.67

(Unlike his sons, the elderly family patriarch Mustafa Tlass kept an ambiguous silence during the uprising. He passed away in Paris in June 2017, at the age of 85.)68

Syrian authorities appear to have maintained some links to Firas Tlass at first, perhaps hoping to sway him once more, but eventually moved to put him on trial in absentia and sequestrate his property, including MAS.69

On learning this, Lafarge seems to have reasoned that their deal was with Tlass himself, and decided to continue the relationship.70 The Syrian government may have decided to look the other way, since they, too, wanted the plant to remain open—LCS continued to pay taxes in Damascus.71

After breaking with Assad, Firas Tlass turned his attention to dealmaking among the anti-Assad insurgents in the same way as he had previously greased palms among Assad’s officers. “Firas acted very autonomously,” says Wærness. “He had his own political thing going on, but a common understanding evolved that since he was already in touch with these rebel factions, he could also make life easier for the factory.”72 Although LCS executives had their doubts about Tlass’s reliability as an opposition interlocutor, they didn’t have many options.73 In those days, Tlass was “our only source of information,” recalled Frédéric Jolibois, who would succeed Bruno Pescheaux as head of LCS in 2014.74

According to Wærness’s account, Firas Tlass’s interventions appear to have taken three forms: (1) he helped negotiate deals over raw materials, (2) he facilitated Wærness’s work by putting him in touch with rebel leaders, and (3) he paid protection money to armed groups so that they would leave the factory and its transports alone. A look into the public record seems to confirm this account.

In 2012, LCS had signed a deal with the General Establishment of Geology and Mineral Resources, a state body in Damascus, to purchase a volcanic ash known as pozzolana from a quarry east of Raqqa. The plan was derailed when anti-Assad insurgents attacked Raqqa, gaining full control over the city in March 2013.75 With production now at risk, it apparently fell to Firas Tlass to use his persuasive and pecuniary powers to establish a new arrangement. Several months later, Raqqa’s new rebel rulers agreed to let deliveries resume, presumably after getting what they asked for.76

Tlass also invited Wærness and LCS administrative director Marc Castel to “a sort of speed-dating session” with rebel leaders at the five-star Tuğcan Hotel in Gaziantep, Turkey, in September 2012. “I can’t recall the exact names of the groups we spoke to,” Wærness says, five years later, “but they were called things like the Eagles of the Desert, lots of names like that.”77 In all, representatives of five factions appear to have been present.78

Wærness told them about the factory’s situation and said LCS wanted to stay out of the war and continue making cement. The commanders nodded and agreed, and several of them quickly came up with plans for how to protect the factory, generally involving some form of LCS sponsorship for their faction.

Although LCS would occasionally hire rebels from Manbij and Jarablous as armed escorts or pay them to smuggle employees and contractors across the Turkish border, the company did not want to fund armed groups directly.79 But it didn’t matter, because the rebels would get their money anyway—from Firas Tlass.80

“Concretely, our local partner, Mr. Tlass, discussed with the rebel factions and paid out a little money so that our employees would not be troubled,” former LCS CEO Bruno Pescheaux later explained to French investigators.81

According to Pescheaux, who headed LCS until summer 2014, the company paid between $80,000 and $100,000 per month to Tlass, on the understanding that he would pass money onward to locally influential armed factions.82 The YPG seems to have received the largest share, but money also found its way into the hands of various Free Syrian Army-branded groups. Most controversially, money ended up with the rising powers in Raqqa: al-Qaeda’s Nusra Front and the Islamic State, also known as ISIS.83

Wærness says the company was never in doubt about what was going on. It was “clear to us that a terrorist group controlled the quarry and the rest of the city from early summer 2013,” he would later write in a tell-all memoir about his time at the factory. “Because of this, it was especially important that the relationship would be handled by Firas’s middlemen, since an exposure of this sort would have been compromising for LCS. But via Firas, we did in fact contribute to the economy of ISIS.”84

The Nusra Front and the Islamic State had initially been embedded in the same organization, but split in April 2013. At that time, they shared control over Raqqa with several non-designated groups, such as the Islamist faction Ahrar al-Sham and the Ahfad al-Rasoul Brigades, a self-identified Free Syrian Army group.85 Over summer 2013, the Islamic State began to harass and attack competing groups, gradually achieving dominance.86 In January 2014 it violently destroyed all remaining opposition, seizing sole control over the city.87

Documents that appear to originate with an internal probe commissioned by LafargeHolcim indicate that some $15.3 million were paid out by LCS to insurgent middlemen, suppliers, or armed groups during the company’s time in Syria.88 According to the documents, the authenticity of which cannot be independently confirmed, this figure includes money paid to Firas Tlass and MAS ($4.16m), as well as “security payments” channeled via Tlass ($5.38m), and payments to various other middlemen and suppliers of raw materials, including Raqqa-based traders selling pozzolanic ash under the watchful eye of the Islamic State.89

As for Tlass’s “security payments” to armed factions, the shares allotted for each group must have fluctuated over time, but Pescheux has claimed that the Islamic State would at some point receive a monthly $20,000 cut.90 For comparison, the average salary of an anti-government fighter in Syria may have been in the vicinity of $100 or $200 per month, though reports vary considerably.91

Changing of the Guard

Wærness had decided already in early 2013 not to renew his two-year contract, which was set to expire in September that year. He claims to have become increasingly concerned not only for his safety—he was now forced to spend much of his time in Turkey, hunkering down in the backseat of his car to pass jihadi checkpoints when traveling to the factory—but also by the situation in general. LCS seemed to be a “sinking ship,” which could not indefinitely survive the parasitism and violence of the armed groups.92

Extremist influence radiating from Raqqa had quickly grown into a major problem after the rebel takeover there in March 2013. Wærness was repeatedly invited to meet with Islamic State representatives, but declined. In August 2013, he was handed an arrest order signed by an Islamic State security official in Raqqa, which declared that both Wærness and Marc Castel were wanted on charges of collaboration with Assad’s government, to which LCS continued to pay taxes.93 Ironically, Wærness also appears to have been wanted by Syrian intelligence.94

Wærness says he informed superiors in Paris that the Islamist takeover in Raqqa had made the situation untenable, but was frustrated by their refusal to take action. In October 2013, he was finally escorted by his contacts in the YPG and a rebel group from Manbij to the border crossing in Jarablous, which was now, like much of northern Syria, under joint control of the Islamic State and other rebels. Exiting safely, Wærness would later work for a time with Lafarge in Europe, but he eventually quit and published a memoir about his time at the factory.95

Jacob Wærness was succeeded as risk manager at Jalabiyya by Ahmed Jaloudi, a Jordanian man he had helped select and train. Internal company emails leaked to Syrian and French newspapers indicate that on Jaloudi’s watch in late 2013 and 2014, LCS seems to have been regularly in touch with the Islamic State, which was at that point a powerful presence in the area. The leaked documents suggest that the Jordanian routinely negotiated with Islamic State leaders on LCS’s behalf, with one former employee telling Le Monde that Jaloudi “moved constantly between Gaziantep, Raqqa, Manbij, and the factory.”96

Even as LCS moved deeper into the darkness of the Syrian war economy, Firas Tlass’s connection to the company was becoming weaker—or at least more obscure.

Though Syrian authorities had taken custody of MAS in 2012–2013, Tlass remained on the board of LCS until the beginning of 2014 when, according to a company spokesperson, he left “for reasons unrelated to Lafarge.”97 In August 2014, the Syrian Ministry for Internal Trade and Consumer Protection announced that MAS had been formally transferred to state ownership, which meant Assad’s government now controlled a 1.33 percent share in LCS.98 LCS’s various streams of payment to Tlass appear to have dried up in July and August.

The timing may suggest that LCS simply responded to the Syrian ministry’s decision by pushing Tlass out of the company. But that isn’t necessarily so, because there was another excellent reason to stop paying Tlass at this time: in September 2014, cement production at Jalabiyya ended.

The End of the Jalabiyya Factory

Through 2011 and 2012, the factory at Jalabiyya maintained a high production rate despite the growing conflict. In 2013 the pace slackened for lack of raw materials, maintenance, and expertise, while sales prices came under pressure from Turkish cement smuggled into Syria by rebel groups. By 2014, the factory was rarely functional, with LCS having long run their operations at a loss.99

Even so, the Lafarge board in Paris was determined to keep LCS in business. Though they seemed to be throwing good money after bad, company executives must at this point have had Syria’s post-war future in their sights. “Lafarge’s cement plant was Syria’s largest private sector investment in Syria outside the oil sector so the stakes were really high for them,” says Jihad Yazigi, the Syrian economist. “Given their large production capacity they were also ideally positioned to benefit from a potential reconstruction so you can imagine how important it was for them to protect it.”100

If that was the plan, it didn’t work. Just like those secular Syrian opposition members who had tried to ride the jihadi tiger, Lafarge would soon find it turning against them.

In 2014, the Islamic State seized vast areas of Iraq and Syria, including rebel-held Raqqa and Manbij.101 After taking Mosul, Tikrit, Tel Afar, Sinjar, and other cities in Iraq that June, the group’s strength snowballed.102 In August, jihadi forces poured out of Raqqa to seize the Syrian army base at Ein Eissa; they then swiftly overran the last government positions in the province, near the Tabqa dam. Dozens of soldiers were gruesomely executed before the camera, throats slit and heads severed.103

As the summer drew to a close, only the Kurdish fighters of the YPG continued to put up meaningful resistance to the jihadi surge north of Raqqa, barring the Islamic State’s route to the Turkish border from their stronghold at Kobane.104

Jalabiyya was increasingly exposed, but LCS representatives continued to haggle with the jihadis over the protection of employees, rights of passage, and raw materials. However, once the Islamic State moved to finish off the YPG, it was over.

In mid-September, the jihadis once again lunged north from Raqqa, gobbling up Kurdish villages and sending tens of thousands of civilians fleeing toward Turkey.105 Those LCS employees who were still at Jalabiyya fled in panic when the jihadis arrived on September 19.106 Propaganda videos released by the Islamic State show a handful of fighters driving slowly between long rows of eerily deserted but mostly unharmed factory buildings, as thick black smoke billows across the sky.107

And that was that. Left without any property to maintain and protect, Lafarge finally gave the order to terminate LCS operations in Syria.108

From Cement Plant to Training Camp

Having seized the factory, the Islamic State tried to restart production and lure back former managers.109 They had no success, and the LCS factory appears to have laid dormant while the Islamic State struggled with a small garrison of Kurdish fighters at Kobane, where U.S. airstrikes turned the tide from September 2014 onward.110

The combination of Kurdish ground forces and American air power proved too much for the jihadis, and in February 2015 the YPG broke out from Kobane.111 It did not take long for the Kurds to reach Jalabiyya. YPG propaganda videos show young fighters marching through high grass toward the factory silos, running up stairwells, and breaking into rooms recently occupied by their jihadi enemies. A YPG volunteer who passed through Jalabiyya a few months later tells me some buildings at the LCS plant were damaged in the attack, but repairs were soon underway.112

The YPG and its allies moved on to take the October Dam bridging the Euphrates in December 2015. Manbij fell after a hard-fought siege in August 2016, and the noose then began to tighten around Raqqa, even as the Syrian army, backed by Russia and Iran, attacked Islamic State positions further south. The jihadis were finally expelled from Raqqa in October 2017, and their “caliphate” began to crumble.113

Safely embedded in a YPG-controlled autonomous region called the Democratic Federation of Northern Syria, the LCS plant at Jalabiyya appears to have survived the war—physically, at least. It no longer seems to be at risk of attack.

However, instead of cement, the factory now produces guerrillas. At some point in 2015, it was turned into a base for U.S., British, and French special forces.114 Although reporters remain banned from the area, satellite pictures show American military helicopters and Osprey aircraft parked all across factory grounds, and sources in the region tell me Jalabiyya also houses a training camp for U.S.-backed Kurdish and Arab fighters.115

The French Investigation

The Syrian opposition newspaper Zaman al-Wasl broke the story of Lafarge’s alleged payments to the Islamic State in February 2016, after receiving several leaked emails from unknown sources.116 A few months later, France’s Le Monde picked up the story, which sparked outrage in a nation still mourning the victims of several Islamic State attacks.117

Later that year, human rights activists and former LCS employees launched a lawsuit against Lafarge.118 In the lawsuit and in press reporting, the company has been accused of financing the Islamic State and the Nusra Front, violating EU sanctions by buying Syrian oil, and endangering its employees by failing to organize an orderly evacuation.119 French authorities initiated an investigation in October 2016.

Although LafargeHolcim refuses to admit to any legal wrongdoing, the company is now publicly contrite about its “significant errors of judgment” and says LCS should have been closed much earlier.120

In April 2017, LafargeHolcim’s French-American CEO Eric Olsen resigned, saying that although he had “absolutely not” been involved in the Syrian affair, he hoped that this would be a way to bring back “serenity to a company that has been exposed for months on this case.”121

That plan, too, has worked out poorly.

In September 2017, three former LCS employees were flown to Paris to testify, confirming that bribes were paid to the Islamic State.122 In October, Syrian and other Arab media outlets reported that Firas Tlass had been arrested in the United Arab Emirates, possibly in connection with the Lafarge probe (though other information pointed to unrelated charges), and, the following month, police raided LafargeHolcim offices in Paris and Brussels.123 Then, in December 2017, French authorities began to place several current and former senior Lafarge executives under investigation. Those indicted included former Lafarge CEO Bruno Lafont and his successor at LafargeHolcim Eric Olsen, as well as Bruno Pescheux and Frédéric Jolibois, the two presidents of LCS.124

Though reluctant to discuss the case in detail, LafargeHolcim’s head of media relations Beat Werder tells me the company is sorry about what happened in Syria. “I think small errors of judgement led to other errors of judgment, and it just deteriorated further,” Werder says. “This is how we see it today, and we condemn and regret what happened.”125

Yet, the most important thing to understand about Lafarge’s Syrian misadventures is perhaps that they were not unusual at all. By bending to threats and trying to appease all sides, LCS seems to have acted like most Syrian companies—and beyond questions of right and wrong, this sordid affair provides us with an instructive glimpse into Syria’s murky war economy.

The Syrian War Economy

The inequality and racketeering that characterized Syria’s pre-2011 economy has not disappeared during the war. If anything, the conflict seems to have left the Syrian business elite even more crooked and conceited, and ordinary people even more exploited and despondent.126

Instead, the old structures have mutated and blended with new networks of illicit enrichment, many of them sprouting among foreign-backed rebels, jihadis, and Kurdish forces. In this oligarchy of violence, commercial actors compete both more openly and more violently than in the pre-2011 era, when transactions took place under the umbrella of the police state.

“The networks that shape the war economies betray the territorial divisions of the armed conflict itself,” says Samer Abboud, an associate professor at Arcadia University and author of a Century Foundation report on the Syrian war economy.127 “I think of them as networks of violence because even though not all of the nodes are violent actors they are implicated in violence in the conflict.”128

Even as Syria’s rebels, Kurdish nationalists, and Assad loyalists fight and kill each other, they trade. A veritable army of political fixers, entrepreneurs, and smugglers has emerged to provide the connective tissue binding this fragmented nation into one single, happily pumping vascular system of corruption.

“What connects the warring parties are these brokers or middlemen who have adopted a position of neutrality to different sides in order to facilitate financial and trade transactions between them,” says Abboud, who is also the author of a recent book on the Syrian war.129

In some ways, this is nothing more than market forces doing their thing in a business environment regulated by military power rather than by laws and bureaucracies. And tellingly, many of Syria’s most successful conflict traders are not veterans of the battlefields, but of the boardrooms.

Businessmen Who Turned Middlemen

Though there are many of these conflict traders,130 the most well-known figure working Syria’s political gray zones may be George Heswani, a Damascus-based businessman with close links to Assad’s circle and to economic interests in Russia.

Heswani and his company, Hesco, are said (though they deny it) to have spent years brokering deals to ensure that oil and gas would continue to flow from eastern Syria to state-run power plants further west—deals not unlike those made by LCS, but on a larger scale and in a more forthright fashion. In 2015, Hesco was reported to be paying the Islamic State about $50,000 a month to retain access to a gas plant near Raqqa, even as the army and the jihadis continued to kill each other a short distance away.131

“Think of it as tactical manoeuvres to improve leverage,” an owner of a Syrian energy company told the Financial Times. “This is 1920s Chicago mafia-style negotiation. You kill and fight to influence the deal, but the deal doesn’t end.”132

In 2015, the United States and the European Union sanctioned Heswani for his deals with the Islamic State.133 Western officials have also frequently pointed to the eastern Syrian oil trade as evidence that Assad is in a business relationship with UN-designated terrorists.134 It was true, but they have tended to leave out an important piece of context, namely that their own rebel and Kurdish allies also traded with the Islamic State.135

Whether any of this seems scandalous will likely depend on one’s ability to disregard the obvious: everyone in Syria needs oil, and, for a year or two, the Islamic State controlled most of the oil in Syria. The list of buyers consequently included Assad’s government, the YPG, the Nusra Front, all manners of rebel factions and other Islamists, and even, it would seem, a French cement maker—that is, everyone.

One may choose to view this as a grand conspiracy or simply as the invisible hand of the market being busily at work. More prosaically put, it is perhaps how the economy would operate in any war zone where rival factions control interdependent resources.

The Reconstruction Conundrum

The past seven years of civil war have wrecked Syria’s economy, destroyed its cities, and created immense human suffering. Hundreds of thousands of people are thought to have been killed, and about a quarter of the population has fled abroad—at least 5.5 million refugees now live in neighboring countries, another million in Europe. Another six million people are thought to be internally displaced inside Syria’s borders. Major cities like Damascus, Aleppo, Homs, and Raqqa have been partially destroyed by the war, and the economy is in shambles. Two-thirds of the population still left inside Syria needs foreign aid to get by.136

The conflict won’t be over soon, and Syria may remain a divided country for a long time—maybe indefinitely. But with Bashar al-Assad’s government no longer facing a serious threat either from foreign-backed Sunni Arab rebels or independent jihadis like the Islamic State, and with full-scale fighting between Assad’s forces and the Kurds unlikely due to Russian-American deconfliction agreements, a corner seems to have been turned.

Assured of its survival, the Syrian government is working hard to persuade the world that it is time to rebuild Syria through a UN-led reconstruction program.137 International cost estimates for Syria’s reconstruction are in the $200-billion range, which means it is impossible for Damascus to manage this gargantuan task by itself—the Syrian state budget for 2018 was only worth about $7 billion.138

Nowhere is the scale of the problem clearer than in the Homs, Syria’s third-largest city, which was under partial rebel control from late 2011 to early 2014.139 Four years later, the recaptured areas should be a showpiece for Assad’s ability to rebuild his country with private investments and Russian, Iranian, and Chinese assistance—but instead, they demonstrate the economic impotence of the pro-government camp. Apart from the symbolic restoration of religious monuments and cultural landmarks, formerly rebel-held areas like Baba Amr and the Old Town are still uninhabited ruins.140

To rebuild Syria and provide even the most rudimentary conditions for refugee return, Assad will need UN assistance. His own allies are traditionally stingy aid donors, or poor, or both, and the vast majority of funds for a credible reconstruction program would almost certainly have to come from wealthy nations like the United States, EU members, Norway, Switzerland, Japan, Canada, and the Arab oil states, most of whom oppose Assad’s rule.

Though these so-called Friends of Syria have mostly given up on overthrowing the Syrian leader, they have instead committed to a strategy of conditional economic isolation, trying to use sanctions relief and reconstruction aid as carrots to coax Assad into resigning. Which, of course, he won’t do—but the policy remains in place anyway, formally motivated by a lingering commitment to regime change in Syria.141

Still, many of these nations remain eager to do something, whether for humanitarian reasons or to stem the flow of refugees from Syria. The emerging “third way” solution is to maintain economic pressure on the Syrian central government, while directing reconstruction funds to areas outside of Assad’s control.

The biggest such area, perhaps the only one that could be truly viable, is YPG-held northeastern Syria. This region also benefits from fears among Western nations that the Islamic State could respawn among the hundreds of thousands of desperate Sunni Arab civilians who live in the area, displaced by the fighting and often resentful of Kurdish rule.

Northeastern Syria certainly needs a reconstruction program to get back on its feet. While parts of the countryside and some Kurdish-majority cities, like Qamishli, have taken very little damage, other cities like Kobane, Manbij, and Raqqa were virtually destroyed by U.S. bombing during the YPG-led campaign to kick out the Islamic State. Nearly half a million people were forced to flee their homes in or around Raqqa between November 2016 and September 2017, and few have returned. “One hundred and thirty-five days of clashes created huge destruction in the city,” a Kurdish official told me by phone from Ein Eissa in October, warning that the area was full of land mines and unexploded ammunition. “As of now, we cannot tell civilians to come back to Raqqa, because it’s dangerous.”142 Still today, many of the city’s former inhabitants remain scattered in miserable camps across the northern countryside.143

In terms of institutional capacity and resources for reconstruction, the YPG and its allies are much worse off than the Syrian government. But unlike Assad, the Kurds have spent the past few years making friends among the world’s wealthiest nations.

The United States has announced that it will remain in the Syrian Kurdish region for the foreseeable future, protecting it from both Turkey and the Syrian government. American officials point to a need to continue suppressing the Islamic State, but also say they hope to leverage the oil, water, and agriculture of northeastern Syria to persuade Assad to resign and his Iranian allies to exit Syria. That’s fanciful, but, nevertheless, it seems to be the strategy currently at work.

Endowing northeastern Syria with a functioning economy and decent governance is intrinsic to any such strategy. Unless the area can get back on its feet, provide public services, and create jobs, it cannot be a reliable protector against renewed instability, much less hold its own when bartering over resources with Syria’s central government.

At this point, the current U.S. administration stumbles over its own ideological barriers. U.S. President Donald Trump campaigned on cuts to foreign aid and a refusal of “nation-building,” and there’s little readiness within his administration for an open-ended commitment to building Syrian Kurdistan—not to mention the friction that would create with Turkey. When he rolled out the new U.S. Syria strategy at a speech at Stanford University in mid-January of this year, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson consequently said the United States would restrict itself to providing basic “stabilization” assistance, and would not go so far as to supporting “reconstruction.”144

What that means is that U.S. diplomats and USAID workers will deploy to Syria to help supply short-term necessities and security-related items such as training and equipment for de-mining, rubble-clearing, electric power, clean water, and the standing-up of internal security forces and border patrols.145 Reconstruction, which the U.S. government will not support, would involve rebuilding Raqqa and other cities, organizing a comprehensive return of displaced civilians, developing a functioning local economy, creating jobs, and supporting credible, permanent governance structures.

However, Tillerson added that others are welcome to do what the United States will not, saying he would “encourage international assistance to rebuild areas the global coalition and its local partners have liberated from ISIS.” That seems to be a pitch for support from European nations and perhaps others—in October, U.S. officials brought a Saudi minister to Ein Eissa to discuss reconstruction needs.146

In other words, at least some rebuilding is going to take place in northeastern Syria, in isolation from Assad’s government. Whether it stops at very basic efforts or shifts into a full-blown reconstruction program, one thing is certain: it will require a lot of cement.

A Return to Jalabiyya?

A LafargeHolcim spokesperson says the company has no plans to return to Jalabiyya.

“The plant is closed and we have no intention to reopen it,” I’m told by head of media relations Beat Werder in a phone interview. “I guess theoretically it is still our property, but it is not in our books anymore, so accounting-wise it was written off.”147

That may be LafargeHolcim’s current position, but it is unlikely that the company has given up entirely on its Syrian assets.

Apart from having been commandeered by the U.S. government, the Jalabiyya plant seems to have suffered little structural damage.148 With some repairs and a reassembled workforce, it could likely be restarted quickly.

As things stand, the security situation in the Jalabiyya region is better than at any point since 2011. Since last autumn, the area between Raqqa, Manbij, and Kobane is entirely controlled by the YPG and its local Arab and Syriac allies, who have declared themselves the army of a Democratic Federation of Northern Syria.149 This internationally unrecognized but increasingly real political entity is watched over by what is in the Syrian context an invincible power: the U.S. Air Force.

To be sure, there are rival forces not far away. The Syrian army, which is just as untouchable due to protection from the Russian Air Force, has consolidated control in Aleppo and south of Raqqa. Turkish troops are embedded among Arab and Turkmen rebels west of the Euphrates, in a triangle stretching from Jarablous to al-Bab and Azaz, north of Aleppo. They are currently fighting YPG forces to the northwest of Aleppo, in the Efrin enclave. But neither Assad’s government nor Turkey and its rebel clients could punch through the YPG to take Jalabiyya in the east, unless the United States decides to let them.

The Democratic Federation of Northern Syria is at this point large enough to provide safe land connections from Jalabiyya to most of the relevant markets and sources of raw materials. There are open roads to the pozzolana quarry outside Raqqa, to the hydroelectric dam at Tabqa, to several major Syrian oil fields, to the Iraqi border, and to Qamishli, from where there is regular air traffic to Damascus. Cement could reach Manbij, Kobane, Raqqa, Hassakeh, Ras al-Ein, Amoude, and Qamishli, without crossing into anti-YPG territory.

Kurdish leaders would likely be thrilled to see Jalabiyya back in business. Restarting the factory would boost the local economy and radically improve the chances for a YPG-controlled reconstruction of cities like Manbij, Kobane, and Raqqa. It could also give the Democratic Federation some badly needed economic leverage vis-à-vis the central government—and of course, the Kurds could also take the opportunity to impose lucrative fees and taxes, like in the good old days.150

Then again, YPG-backed authorities do not seem capable of running the factory on their own, even if LafargeHolcim were to reinvest in the area. The Democratic Federation rests on shaky legal ground, since it has no international recognition (not even from its sponsor, the United States) and it has only limited administrative and institutional capacity. In fact, Kurdish-controlled northern Syria remains dependent on Assad’s government, which still controls much of the bureaucracy in the northeast. Even under overall YPG control, state employees continue to administer public services, salaries, and pensions, and they and other loyalist actors have a hand in the Kurdish region’s educational sector, health care, air travel, financial services, and oil and gas extraction—the YPG’s lifeblood.

The Jalabiyya factory would likely also need at least some resources brought in from the coast or other army-controlled areas, which could give Damascus even more influence over its operations.

In other words, for the factory to restart under YPG control, the Assad government and/or allied traders would almost certainly have to approve and be adequately rewarded.

Damascus wouldn’t necessarily mind. Assad, too, has an interest in reviving the economy and restarting the northern cement trade, especially if that helps him rebuild Aleppo. If making a deal over Jalabiyya with the Kurds could also restart the flow of tax payments from LCS to state coffers, and allow his government to publicly welcome a European multinational back to Syria, so much the better. And the Syrian leader will want to tread carefully in his dealings with the Kurdish region, finding a middle course between empowering it too much and allowing it to spin off into isolation under U.S. tutelage. Making sure that government institutions and loyalist businessmen remain intimately involved in Syrian Kurdistan’s strategic industry may be his best way to preserve long-term leverage and discourage separatism.

Another possibility, of course, is that the United States will decide to use its military and economic might to help the YPG sidestep Damascus. U.S. officials appear to be well aware of the role the Jalabiyya factory could play for reconstruction, and, if they really want to, the Americans could certainly muster the necessary expertise, financial muscle, resources, and logistics to cut Assad and his allies out of its operations. Such interventions in the local economy would help expand the the Democratic Federation’s autonomy from Damascus, and they would seem to fit well with the U.S. strategy of weakening Assad by economic means. But they also run up against the stated U.S. reluctance to nation-build, not to mention that any attempt to delve deeper into the Kurdish economy would spark Turkish protests and attempts at obstruction.

How LafargeHolcim fits into these scenarios remains to be seen. Whether convicted of terrorism financing or not, the Swiss-French company retains 98.67-percent ownership of LCS and thus also of the factory at Jalabiyya. The remaining 1.33-percent share that formerly belonged to Firas Tlass has been confiscated by the Syrian government, but LafargeHolcim seems to be in no hurry to crack open that can of worms. Very likely, the company will simply wait to see which way the wind blows before deciding whom to consider the legitimate authority over northeastern Syria.

Destruction, Corruption, Reconstruction

Before 2011, corruption in Syria manifested itself through politically engineered state–business partnerships and, increasingly in Bashar al-Assad’s era, an untouchable caste of regime-linked private-sector tycoons. During the war, it has mutated into a many-headed hydra of armed actors running their own rent-seeking operations and trade networks. The continued need for trade and other exchanges across military front lines has given rise to a new niche for fixers and conflict traders who interpose themselves between the warring parties.

One could argue over whether it was morally acceptable or not for Lafarge to continue doing business in such an environment. On the one hand, the company fed money into the illegal economy and paid armed groups. On the other hand, ordinary Syrians needed cement for a variety of legitimate and even laudable purposes—how else to rebuild bombed hospitals?—and this was the only realistic way to continue producing it. Either way, it was likely impossible to continue working at Jalabiyya in a way that also conformed to the legal requirements under which a European company operates. Lafarge is now suffering the consequences of its attempt to skirt that fundamental contradiction.

Similar dilemmas will apply to a great many other commercial actors in Syria, as well as to humanitarian organizations that need to reach across the front lines in order to reach vulnerable civilians. All of them are sure to be watching the outcome of the French investigations for clues on how to adjust their own relationships among Syria’s economic middlemen and armed actors.

These issues are taking on an added importance given that outside actors are now deliberating ways to spend reconstruction money in Syria. An influx of foreign aid money into a still-divided country would further modify the economic relationships formed during the war, possibly reinforcing the role of those mostly regime-linked middlemen who hold the keys to particular types of cross-line trade.

Should American and European policymakers double down on their investment in the Democratic Federation of Northern Syria even as Assad consolidates control over most of the rest of Syria, the country may end up being informally partitioned for the foreseeable future. Each Syrian region would then be more or less politically independent of the other, yet they would undoubtedly remain linked by residual institutional ties and informal trade networks that, for the most part, run back to Damascus. It would ensure many more years of good business for Syria’s conflict traders, potentially empowering them vis-à-vis the central government and its institutions while, paradoxically, also helping Assad maintain a degree of influence over the Kurdish leadership.

In the longer term, the future of northern Syria is highly uncertain. But if local and international interest continues to drift in the direction of reconstruction, that little spot of windswept grasslands in Jalabiyya may well assume a new importance. Even as the cities around it lie in ruins, there it stands, nearly untouched by the war, a silent monument to the power of money: Lafarge’s giant cement plant, waiting for another handshake across the front lines.

This work was supported, in part, by a research grant from The Harry Frank Guggenheim Foundation, and by the Carnegie Corporation of New York.

Editor’s note: This report was updated on February 21, 2018, to reflect new information regarding the charges against Firas Tlass.

Notes

- Linda Tom, a Damascus-based official with the UN’s Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), told me in October 2017 that more than four-fifths of Raqqa city had been rendered uninhabitable. For more, see Aron Lund, “The Islamic State Is Collapsing, but Raqqa Is in Ruins,” The Century Foundation, October 18, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/islamic-state-collapsing-raqqa-ruins; Aron Lund, “Winter is coming: Who will rebuild Raqqa?” IRIN News, October 23, 2017, https://www.irinnews.org/analysis/2017/10/23/winter-coming-who-will-rebuild-raqq.

- The French company Lafarge and Switzerland’s Holcim merged in 2015 to create LafargeHolcim. “Holcim and Lafarge complete merger and create LafargeHolcim, a new leader in the building materials industry,” Lafarge, October 7, 2015, www.lafarge.com/en/holcim-and-lafarge-complete-merger-and-create-lafargeholcim-a-new-leader-building-materials-industry.

- “Top Lafarge executives, including former CEO, indicted on terror financing charges,” France 24, December 9, 2018, www.france24.com/en/20171209-senior-lafarge-executives-including-former-ceo-indicted-terror-financing-charges.

- Liz Alderman, “Lafarge Scandal Points to Difficulty for Businesses in War Zones,” New York Times, April 24, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/04/24/business/lafarge-ceo-syria-cement.html.

- Aron Lund, “Rebuilding Syria’s rubble as the cannons roar,” IRIN News, March 8, 2017, https://www.irinnews.org/analysis/2017/03/08/rebuilding-syria’s-rubble-cannons-roar.

- Transparency International ranked Syria among the Arab world’s most corrupt countries in 2010. Syria shared 127th place on the list with Lebanon, and of the five Arab states that ranked worse—Mauritania (143), Yemen and Libya (146, shared), Sudan (172), and Iraq (175)—three were in the midst of violent conflict and one had suffered a different kind of disaster: being ruled by Colonel Gaddafi for the past half century. For the full report, see “Corruption Perceptions Index 2010,” Transparency International, 2010, https://www.transparency.org/cpi2010/results.

- Or “children of authority” in the translation preferred by Salwa Ismail, “Changing Social Structure, Shifting Alliances and Authoritarianism in Syria,” in Fred Lawson (ed.), Demystifying Syria (London: Saqi Books, 2009).

- Bassam Haddad, Business Networks in Syria: The Political Economy of Authoritarian Resilience (Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 2012), p. 76. In the pre-war period, Rami Makhlouf was so widely loathed among ordinary people in Syria that the United States saw sanctioning him as a way to win Syrian hearts and minds. See for example “Maximizing the impact of Rami’s designation,” U.S. diplomatic cable released by Wikileaks, 08DAMASCUS70_a, January 31, 2008, https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/08DAMASCUS70_a.html.

- Author’s interview with Riad al-Turk, Damascus, January 2008.

- “Lafarge to Buy Orascom Cement for $12.8 Billion,” Reuters/CNBC, December 10, 2007, https://www.cnbc.com/id/22178287.

- Orascom and MAS had originally created a company called the Syrian Cement Company (SCC) to build the factory. It would be majority-owned by Orascom Cement with a minority stake of 25 percent left for MAS. When Lafarge stepped in, the name was changed to Lafarge Cement Syria (LCS). MAS’s share of LCS dwindled as Lafarge continued to put more money into the project. By the time the factory entered production, MAS retained 1.33 percent of the ownership of LCS. See “shuraka baina mas al-souriya wa-orascom al-masriyya li-iqamat masnaa lil-isment,” Syrian Days, May 3, 2007, www.syriandays.com/?id=2661&page=show_det&select_page=59. The U.S. Geological Survey Minerals Yearbook—2009, U.S. Geological Survey, https://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/country/2009/myb3-2009-sy.pdf; “Lafarge Cement-Syria Starts Ops, To Hit Full Capacity ’11 -Report,” Zawiya, October 16, 2010, available at www.lafarge.com.sy/lafargeeng.pdf; The U.S. Geological Survey Minerals Yearbook—2011, U.S. Geological Survey, https://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/country/2011/myb3-2011-sy.pdf; Ralph Atkins, Erika Solomon, and Michael Stothard, “LafargeHolcim’s reputation at risk over alleged links with Isis,” Financial Times, March 19, 2017, https://www.ft.com/content/406b06fe-05b6-11e7-aa5b-6bb07f5c8e12.

- Lafarge Cement Syria website (lafarge.com.sy) as captured on July 2, 2013, by the Wayback Machine, https://web.archive.org.

- The U.S. Geological Survey Minerals Yearbook—2008, U.S. Geological Survey,, 2010, https://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/country/2008/myb3-2008-sy.pdf. A similar-sized plant (Al-Badiya Cement) was also being built by Saudi and European investors near Damascus, aiming to ensure a steady supply of cement to southern Syria, while LCS took charge of the north. Cement is heavy to move and sells cheaply per kilo, which reduces the effective range of sales. Together, these two plants were intended to more than double Syria’s cement-production capacity, making the country self-sufficient even in case of rising demand.

- Author’s interview with Jacob Wærness, phone, December 2017.

- Email to the author from Myriam Ababsa, December 2017.

- A decision to allow private investment in the cement sector was made in 2004, with the first licenses awarded in 2005. Email to the author from Jihad Yazigi, Syrian economist, January 2018

- Myriam Ababsa, Raqqa: territoires et pratiques sociales d’une ville syrienne (Beirut: IFPO, 2009), p. 155. Available for free online at http://books.openedition.org/ifpo/1021.

- The author made multiple attempts to contact Firas Tlass up until publication, but received no response.

- Hanna Batatu, Syria’s Peasantry, the Descendants of Its Lesser Rural Notables, and Their Politics (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999), p. 226-227.

- Susanne Koelbl, “A 101 Course in Mideast Dictatorships,” Der Spiegel, February 21, 2005, www.spiegel.de/international/spiegel/syria-a-101-course-in-mideast-dictatorships-a-343242.html.

- There was also his nephew Gen. Talal Tlass, who remained loyal to the government and would in 2012 be appointed deputy minister of defense, and a host of younger, lower-ranking officers, such as Maj. Bashar Tlass, 1st. Lt. Mohammed Tlass, and 1st. Lt. Abderrazzaq Tlass, all of whom defected in 2011–2012 to join the rebellion.

- Salwa Ismail, “Changing Social Structure, Shifting Alliances and Authoritarianism in Syria,” in Fred Lawson (ed.), Demystifying Syria (London: Saqi Books, 2009), p. 19; “The story behind the defection of Syrian general Manaf Tlas,” Al-Arabiya, July 9, 2012, https://english.alarabiya.net/articles/2012/07/08/225199.html.

- “The Procurement of Conventional Military Goods in Breach of UN Sanctions,” Report by the Special Advisor to the Director of Central Intelligence on Iraq’s Weapons of Mass Destruction, U.S. Central Intelligence Agency, September 2004, https://www.cia.gov/library/reports/general-reports-1/iraq_wmd_2004/chap2_annxJ.html. In 2010, Firas Tlass listed the following companies as belonging to MAS Economic Group: “Al-Saker Food Industries Company, Al-Akram for Metal Industries Ltd. Company, Al-Fajr Coffee Roasting and Processing Company, Al-Jabal Al Akhdar Conserves Company, MAS Engineering and Contracting Company, Oras Industrial Contracting Company, MAS for Metal Ends Company, Syrian Meat Processing Company, Syrian-Finnish Company for Dairy Products, Golan Meat Industry Company, MAS Marketing Company, The Commercial Group.” (From www.firastlass.com as captured by www.archive.org on March 9, 2010.)

- Email to author from Jihad Yazigi, Decethe mber 2017. On Yazigi, see Stephen Glain, “The Syria Report Survives as Independent Publication,” The New York Times, December 19, 2012, www.nytimes.com/2012/12/20/world/middleeast/the-syria-report-survives-as-independent-publication.html. The Syria Report can be accessed on http://www.syria-report.com. The name MAS is drawn from the abbreviation of Min Ajl Souriya, which is Arabic for “For the Sake of Syria.” The company markets itself as being more than a money-making enterprise, trying to appear as a patriotic agent of Syria’s economic development against nefarious foreign interests. Firas Tlass’s personal website described him as “a patron of the arts [known] for promoting freedom of thought and being a prominent member of the Syrian intelligentsia.” MAS Economic Group (www.masgroup.net) and Firas Tlass (www.firastlass.com). Both accessed via archive.org.

- France gathers world leaders for Bastille Day parade,” AP/The Independent, July 14, 2008, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/france-gathers-world-leaders-for-bastille-day-parade-867282.html.

- “Total Signs Three Oil and Gas Agreements in Syria,” Total S. A., September 4, 2008, https://www.total.com/en/media/news/press-releases/syrie-total-signe-trois-accords-petroliers-et-gaziers; “Sarkozy’s visit yields victory for French oil company,” 08DAMASCUS646_a, Cable from the U.S. Embassy in Damascus dated September 15, 2008, released via Wikileaks, https://search.wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/08DAMASCUS646_a.html.

- “Bank Audi & Lafarge Cement Syria celebrate the successful closing of the Lafarge Cement Syria project finance facility,” Bank Audi, January 13, 2010, www.bankaudisyria.com/syria/newsroom/press/bank-audi-lafarge-cement-syria-celebrate-the-successful-closing-of-the-lafarge-cement-syria-project-finance-facility-english.

- Christian Chesnot and Georges Malbrunot, Les Chemins de Damas: Le dossier noir de la relation franco-syrienne (Paris: Éditions Robert Laffont, 2014), p. 227.

- Author’s interview with Beat Werder, head of media relations for LafargeHolcim, phone, December 2017.

- Fadi al-Alloush writing for Syria Steps, October 14, 2010, available at www.lafarge.com.sy/lafargeeng.pdf.