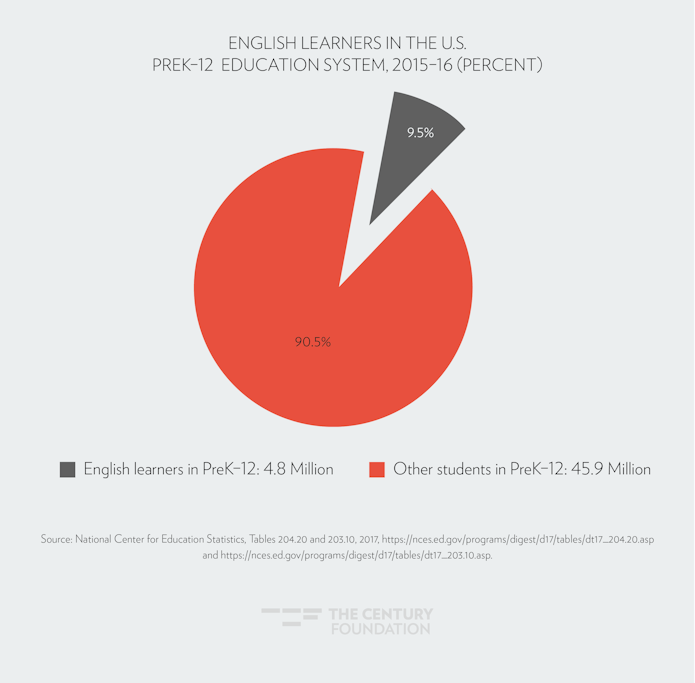

American public schools today are perhaps more linguistically and culturally diverse than at any other point in American history. Over twelve million school-aged U.S. children speak a non-English language at home—about one-quarter of all children between five and seventeen years old. That represents an increase of more than 2.5 million children since 2000.1 Nearly one in ten U.S. students is currently classified as an English learner (EL), and there are one million more ELs in U.S. schools today than in 2000.2 Critically, these children’s numbers are not only growing in traditional immigrant-arrival states, such as California, Texas, New York, Florida, and Illinois, but also in less-traditional immigrant gateway states, such as Alabama, Georgia, and the Carolinas.3 Unsurprisingly, regional and national interest in extending access to equitable educational opportunities for ELs has grown commensurately.

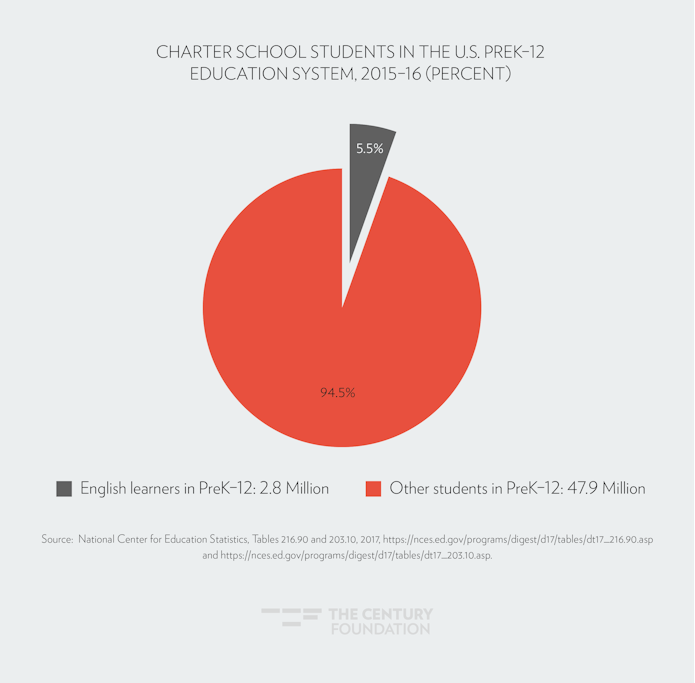

During the same period, charter schools have become an increasingly large portion of the U.S. public education landscape. In 2000, charter schools enrolled just shy of 450,000 students. In 2015–16, charters enrolled over 2.8 million students.4 While this growth has many causes, the charter movement has advanced partly on the strength of promises that these schools can disrupt rigid educational inequities baked into traditional school districts’ enrollment patterns. Charters can provide educational options for historically underserved families who generally would have few alternatives to the schools assigned to them by their school districts.

The question is, then, considering these parallel growth patterns, how can policymakers support charter schools so that they can better meet the needs of the burgeoning community of English learners? What is the experience of ELs in charter schools today? Do ELs have equitable access to charter schools, or do barriers persist? How can the flexibility of the charter model help schools accommodate EL students in unique ways?

Unfortunately, the research on how charter schools serve ELs and multilingual families5 is relatively limited. Furthermore, it is far from clear whether current education policies themselves—both those governing charter schools and those shaping EL education alike—support ELs’ equitable access to, and success in, these schools.

Researchers’ limited engagement with intersections between school choice and linguistic equity is concerning. To be sure, there is no single, obvious answer to the question of whether charter schools—or school choice systems more generally—are good for ELs. The diversity of approaches in the charter sector makes any sort of universal judgment difficult: there are many different charter school models, serving many different communities of students, in states with substantially different laws creating and governing many different types of charter schools.6

What’s more, while ELs are defined as a student subgroup by their still-developing English abilities, this commonality masks their enormous diversity. EL children are a culturally diverse group whose families speak hundreds of different languages at home—including, in many cases, English. While most ELs, when looked at as a national group, speak Spanish at home, in some states and communities the percentages are very different. ELs are diverse in other ways as well. Some are newcomers, with limited or interrupted formal education in their previous communities, while the majority are native-born U.S. citizens who arrive in American schools in pre-K or kindergarten.7

But these challenges do not mean that policy guidance for education leaders who want to improve how charter schools serve ELs is impossible. Notwithstanding the fact of diversity in the EL student subgroup, the differences between charter models, and the variance in states’ charter laws, there are common pitfalls and promising practices that can shape how charters serve EL students. These are identifiable, solvable policy issues across diverse student groupings, schools, and states. For instance, charters often have significant flexibility to offer instructional models that can help ELs succeed; but, also, they sit outside many traditional district structures that typically can support educational equity for ELs. Charter schools can offer alternative educational opportunities for multilingual families; but, also, choice systems governing charter enrollment can be difficult for these families to navigate, for linguistic and cultural reasons.

Charters often have significant flexibility to offer instructional models that can help ELs succeed; but, also, they sit outside many traditional district structures that typically can support educational equity for ELs.

Public education supports for these students have been uneven at best in many communities—in charter schools and traditional schools alike. Notwithstanding the limits of existing research, local, state, and federal policymakers need to ensure that charters serve multilingual families as well as possible. Fortunately, there are a number of ways that local, state, and federal policymakers can reform charter school policies to provide these schools with more and better support and accountability that will help them serve ELs better.

This report explores the intersection between ELs and charter schools and provides ideas for helping policymakers use charters as sources of educational opportunity for a larger number of EL students. It begins with a look at the current experiences of ELs in charters, including things such as demographics and academic performance. It then explores in more depth three issue areas—(1) improving the information multilingual families get about school choice systems and options, (2) using charters’ school-level autonomy to develop school models that meet ELs’ unique needs, and (3) developing meaningful charter accountability for improving ELs’ performance. The analysis and ensuing policy recommendations build upon the most current research on ELs, school choice, and charter schools, as well as dozens of interviews with charter leaders (and other stakeholders) in communities across the country, often during visits to their schools.

Evaluating the Current Situation of English Learners in Charter Schools

Figure 1

Figure 2

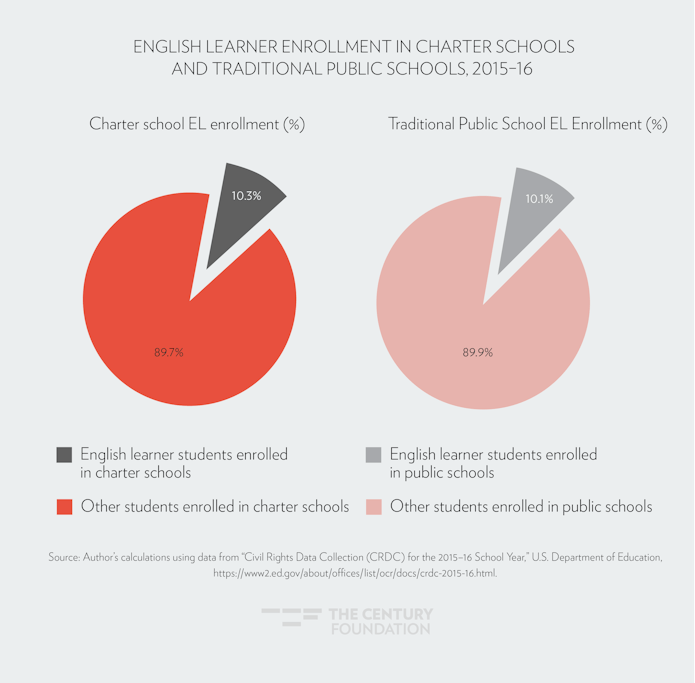

Figure 3

Any analysis of charter schools must engage with—and account for—the diversity in the approaches that these schools take, as well as the wide variation in state charter school laws. Charter schools are publicly funded, privately operated schools. Forty-three states (as well as the District of Columbia) have laws that permit the establishment of charter schools, determine their funding mechanisms, and govern their enrollment practices.8 Most states grant charters significant autonomy over their schedule, staffing, curricula, and budgeting—in return for accountability linked tightly to student outcomes. Ideally, this approach gives charter leaders room to design and organize schools in a way that works with their mission, free from many systemic district and/or state rules. As a result, charter schools span a range of instructional and pedagogical models.

However, charter laws vary significantly from state to state, more so than for traditional public schools. The diversity of charter laws can make precision difficult when discussing them at a national level. For instance, while charter schools are more typically run by nonprofit organizations, the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools reports that just under 15 percent of American charter schools are run by for-profit organizations. 9 Furthermore, collecting data on the sector can be difficult, as it is less likely to be centrally located in district or state records, and some might not be publicly available at all.10

Another complication in evaluating the performance of charter schools and making recommendations to improve their performance is the variety in charter school governance structures from state to state. In some states, these schools are authorized by traditional districts to launch and operate. In other states, the state board of education has this authority. In still others, both of these options are available—or even other entities, such as public universities, independent boards, or other nonprofits, have the authority to authorize and oversee new charter schools’ formation. Charters in each state are subject to different rules and regulations related to public transparency, financial oversight, teacher licensure regulations, and much more.

Simply put, since U.S. charter schools are far from a unitary group, it can be difficult to determine their aggregate or average efficacy at the national level. The largest studies exploring these schools’ impacts on student learning have been conducted by the Center for Research on Education Outcomes (CREDO) at Stanford University. Its studies have found that different states’ charter school sectors have disparate impacts on student performance.

In CREDO’s 2013 report assessing charter school performance across the country, charters in the District of Columbia and states such as Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and New Jersey produced large and positive effects on student achievement. However, in states such as Nevada, Arizona, Texas, and Ohio, the effects on student achievement were negative. Tallying up this range of results, CREDO’s national finding was that charter schools performed similarly to district schools.11

The report’s findings on outcomes for historically underserved students, however, showed somewhat different results, even when combining data from states with higher-quality, higher-efficacy charter sectors and states with lower-quality, lower-efficacy sectors. It found that ELs in charter schools had stronger academic gains in reading and math than ELs in traditional public schools. Charter-attending ELs showed achievement gains valued at “36 more days of learning” each year in both reading and math.12 Academic gains were even higher for charter-attending Hispanic ELs.13

Charter-attending ELs showed achievement gains valued at “36 more days of learning” each year in both reading and math. Academic gains were even higher for charter-attending Hispanic ELs.

But national studies on EL achievement in charter schools may mask state-specific performance. A 2017 CREDO report on Texas charter schools found that, while the state’s charter schools were performing better than they had in previous years, Texas’ “[EL] students in charter schools make less annual academic progress than [EL] students in traditional school settings.”14

In sum, because of these disparities in outcomes and differences in state policy contexts, it is difficult for anyone researching these issues to provide comprehensive policy recommendations that will improve how charter schools serve multilingual families and English learners. While there are some nationally relevant policy recommendations that can be made—such as improving how multilingual families engage with school lotteries and other choice enrollment systems—it is much more difficult to offer recommendations that are simultaneously specific and universally beneficial for, say, how to best incorporate EL students in all states’ charter school accountability systems.

Nonetheless, national and regional growth in the EL population makes it critical that policymakers prioritize EL students and multilingual families when setting or reforming charter school policies. These students—and their families—are increasingly part of the preK–12 student body in almost every U.S. community. Equitable charter school policies must take their needs into account.

Charter schools are one of the most prevalent forms of school choice in the United States, perhaps second only to families buying homes in desired school districts. Support for the charter school model runs the ideological gamut. Some backers argue that charters empower teachers to design schools based on their considerable experience working with children, and run them outside existing district and/or state systems that may stifle their ability to serve children best.15 Similarly, many argue that these schools’ considerable autonomy can make it easier for them to offer innovative education models, including those specifically designed to serve particular student populations.16 Others argue that charters, as schools of choice that generally enroll students without consideration of students’ addresses or academic track records, can empower parents by providing them with school choice delinked from the housing market. Finally, some argue that the existence of charter schools can pressure a district’s traditional public schools to change or improve their offerings by presenting credible competition for the district’s enrollment.17

While each of these theories of action hints at opportunities for multilingual families and EL students, each also suggests challenges. Empowering educators to create schools that have autonomy over hiring, schedule, and curricula is no guarantee that the resulting schools will serve ELs well. It is entirely possible for charter leaders to use their autonomy to design schools that are ill-suited for supporting ELs’ unique linguistic and academic trajectories. What’s more, charters gain their autonomy by sitting outside many systemic supports that a school district can offer. Some of these systems may present traditional public schools with bureaucratic obstacles that impede effective educational opportunities for ELs, but they also can make the classroom-level and school-level work of serving ELs simpler.

Open enrollment policies delinked from the real estate market may open new educational doors for multilingual families, but this removal of barriers is only one step in meaningfully extending access to new educational opportunities.

Meanwhile, open enrollment policies delinked from the real estate market may open new educational doors for multilingual families, but this removal of barriers is only one step in meaningfully extending access to new educational opportunities. Indeed, absent intentional thinking—and sufficient public resources—about the linguistic barriers and cultural differences that may shape how multilingual families view schools, charter schools are unlikely to enroll ELs in large numbers. Further, if charter schools do not enroll many multilingual families—and serve them well—their ability to put pressure on district schools’ enrollment will be seriously undermined, particularly as the population of EL students grows in U.S. schools.18

Fortunately, policymakers can address many of these issues by improving charter school access, tailoring model flexibility, and shoring up accountability measures to account for the needs of the EL community. Support from local, state, and federal policymakers can enhance charter schools as meaningful sources of educational opportunity for ELs and their multilingual families. Indeed, some researchers have suggested that school choice policy reforms focused on these families’ needs can help further immigrant integration into American society. Specifically, school choice systems that engage in linguistically and culturally competent ways with immigrant parents can prepare them to evaluate and navigate American public institutions in ways that transfer to other domains of American life.19

Improving Access to Charter Schools for English Learners

If charter schools are to offer a meaningful alternative to district schools, they must be accessible to all families—including multilingual families. While school choice programs may give multilingual families additional educational options beyond the school or schools assigned to their home address, the value of these options hinges upon whether these families are able to recognize and pursue them. They cannot take advantage of these systems—and effectively pursue their interests through them—if they lack important information about charter school options and/or charter school enrollment policies.20

Researchers are beginning to explore how multilingual families navigate choice-rich school enrollment systems. For instance, a 2014 study found that New York City’s charter schools served a substantially smaller proportion of ELs than did the city’s traditional district public schools.21 While the study found that charter schools were somewhat more effective at reclassifying EL students as proficient in English than traditional public schools, it still found that ELs were less likely to enroll in charters in the first place. “We currently know remarkably little about the underlying causes of these student enrollment gaps,” noted the study’s author, Marcus Winters. However, he noted, the data suggest that “the only policy levers capable of meaningfully decreasing the ELL gap are those that increase the likelihood that ELL students will apply to attend charter schools.”22 Recent studies have discovered similar gaps in application rates, and so there is a growing consensus that multilingual families and families of English learners do not always utilize school choice systems in the same way as do families of English-dominant children.23

A 2014 study found that New York City’s charter schools served a substantially smaller proportion of ELs than did the city’s traditional district public schools.

Multilingual families’ linguistic profiles may play a role in shaping their school enrollment choices. Families that speak non-English languages at home have varying levels of comfort and facility with English. This can shape how they receive information from schools, school districts, and other public institutions about the educational options available for their children—and what information they receive in the first place. Many of these families may not engage with charter schools because public sources of information designed to orient families with their school choice options are often provided solely in English. This challenge can also affect multilingual families’ engagement with their options within traditional public school systems, but in these cases, their children will customarily be assigned to a school. Since families must affirmatively choose to send their children to a charter school, public sources of information can be particularly consequential.

Asked about their access to translation services, administrators at several Washington, D.C. charter schools explained that local resources were insufficient for their needs. Their translation challenges take a variety of forms and are emblematic of difficulties that charters in other communities face. In particular, they said that their schools have difficulty conducting student outreach and recruitment in non-English languages, and that they also do not have the resources or capacity to translate the full range of documents disseminated to multilingual families throughout the school year.24

New York City’s Amber Charter Schools assign Spanish-speaking staff to recruitment sessions and school conversations about identifying ELs for additional supports. It serves “to kind of break the ice,” says school leader Sashemani Elliott. “we just want to know if your child can read, write, or speak in a language other than English. This does not mean that we’re going to take your child in a little room somewhere and that is where they’re going to learn. I think that there has been a stigma around children that speak another language, a language other than English, so we kind of have to say that to them, because that might have been their own experience if they’re new to this country. If, when they were little, when they came in, that was what public education was for them.”25

Cultural variables may also come into play when multilingual families navigate school choice systems. Some multilingual families have limited exposure to American public education. Research has found that children in immigrant families are often less likely to take advantage of school choice systems. This may be because they have limited knowledge of American public institutions, including public schools.26 Michigan State University professor Madeline Mavrogordato, a leading researcher on immigrant families’ engagement with school choice systems, explained the issue as follows: “There’s also an issue of cultural familiarity or cultural literacy . . . meaning that in the U.S., this idea of school choice is pretty well-known and has been underway for quite some time in various forms. But for parents who are immigrants from other places, that may be a completely foreign concept.”27 What’s more, multilingual families headed by one or more recent immigrants to the United States are less likely to have access to social networks comprised of native-born Americans with detailed familiarity about school choice options.28 Given that charter schools only represent a small percentage of all American public schools, these families may be less likely on their own to encounter information on charters as an option, let alone how to apply to and enroll in them.

Multilingual families’ cultural backgrounds may come into play in other ways as well. In some cases, immigrant parents and caregivers have educational preferences that are rooted in cultural practices and convictions that predate their arrival in the United States. One study surveying Indianapolis charter school families about why they chose their children’s schools found that Latinx, white, and African-American families all identified academic performance as the most important factor. The researchers reported “striking similarities” in school choice decision-making across all groups, “despite differences in educational backgrounds and cultural norms.”29 However, there was also some evidence that Latinx parents in the study relied more heavily on word of mouth than other parents, which limited their available choices “to schools that were known within their social circles.”30 Indeed, the Indianapolis researchers found some evidence that bilingual school staff served as particularly valuable conduits for sharing school choice information with Spanish-speaking Latinx families.31

In other words, patterns in multilingual families’ usage of school choice systems may be the visible outcomes of less-visible informational networks shaping multilingual families’ understanding of their school options. In her book on how the children of immigrants navigate school choice options in New York City, Unaccompanied Minors, Seton Hall professor Carolyn Sattin-Bajaj describes this mechanism:

The alignment of students’ social spheres with regard to the task of choosing high schools is a major source of advantage for some choice participants (typically from higher socioeconomic backgrounds) or, on the other hand, a major disadvantage for students without it (often low-income and immigrant-origin). The patterns and themes that emerged in student interviews illuminated the exponential power of receiving consistent, reinforced messages from peers, family members, and school personnel in terms of generating an institutional compass, making informed school choices, and developing research and decision-making skills generally.32

Still, translation and bilingual staff’s facilitation of school choice systems are only the most basic steps toward making open enrollment systems equitably accessible for multilingual families. Policymakers should remain attentive to how new efforts to translate and disseminate information in multiple languages are being received. They should also be mindful that it may need to be provided via multiple mediums. That is, some multilingual families will have low literacy in their home languages, so written translation will not improve their ability to learn about school options. In these cases, education leaders will need to think of alternate ways of making information accessible.

In Houston, Texas, school choice information is provided in multiple languages and bilingual staff are prevalent. While a recent study noted that these efforts “likely put it ahead of other districts when it comes to making school choice more accessible to this group of parents,” it still found that families of Houston ELs were still much less likely to make use of the area’s open enrollment school choice options.33 Despite the steps Houston education leaders have taken to connect multilingual families with information about school choice options, these families still appeared more likely than non-EL families to send their children to the schools assigned to their neighborhoods.34 Similarly, Sattin-Bajaj found that the multilingual families in her New York City study did not see school staff as involved partners in their high school choice process.35

Local efforts to develop and disseminate multilingual information about charter school options should be regularly reviewed to ensure that they are effectively expanding opportunities to multilingual families.

With this in mind, local efforts to develop and disseminate multilingual information about charter school options should be regularly reviewed to ensure that they are effectively expanding opportunities to multilingual families. A look at information dissemination in New York, however, illustrates how difficult it is to strike the right balance. For instance, school pages on New York City’s Public School Performance Dashboard include valuable, specific data on English language acquisition progress and academic achievement information for ELs in every one of the city’s public schools. The pages also contextualize these data by comparing a school’s performance to outcomes at other schools and across the city.36 However, these particular metrics are not clearly visible, and may be difficult for families to find on each school’s data-rich page, not to mention potentially overwhelming. New York State’s school report cards, by contrast, provide much less—and less specific—data on EL performance: more accessible, but less helpful.37

It can be tempting to think of these options in opposition, and to suggest that policymakers should find the “natural” or “moderate” balance between detailed data and accessible data on EL performance. But this mistakes the purpose of collecting and publishing student achievement data. Policymakers should explore how to curate and publish as much EL performance data as possible, with an eye to making it as useful as possible for multilingual families trying to choose a school for their children. That is, the answer should not be to trade data comprehensiveness away in the interest of simplicity, but to maximize both comprehensiveness and accessibility, to make as much EL data as possible accessible for as many multilingual families as possible. This begins with translation, but will also necessarily involve engaging multilingual communities to learn what information they want about their schools—particularly as it pertains to ELs’ linguistic and academic development (as well as the most effective ways to deliver that information).

To be fair, it can be complex for leaders to determine how best to make more data available and accessible to multilingual families. Some of these communities may engage with public education information differently than other communities. In her study, Sattin-Bajaj found that, while privileged white families “associated long-term educational and mobility outcomes with high school assignments and experienced considerable anxiety, [low-income Latin American immigrant parents] viewed high school choices as little more than another bureaucratic procedure typical of schooling in the United States. They accordingly gave it only perfunctory consideration.”38 For school choice programs to serve ELs and multilingual families well, local education leaders will need to listen and work intentionally to explain families’ different school options as well as the publicly available means of differentiating between them.

Beyond multilingual families’ access to information and school choice systems, there are additional EL access concerns related to charter schools. Given that these schools generally enroll students through an open lottery process, it can be difficult for school leaders to intentionally shape their schools’ demographics. On the one hand, this is as it should be. Charter schools have advanced as a policy idea largely because they offer an option for families dissatisfied with their traditional public school choices. Any policy that gives charter schools control over which students they serve risks undermining this argument for charter schools. Any policy that gives additional weight to particular students or student subgroups in charter lotteries also invites the possibility of abuse by privileged families who might not have been the intended beneficiaries.39

However, in communities with shifting student demographics, open enrollment lotteries can also undermine particular school models, especially those designed around linguistic diversity. This is a particular challenge for two-way dual language immersion charter schools that rely upon a linguistically integrated student body to work best. These schools tend to be particularly effective for English-learning students, but they have become increasingly popular with English-dominant families as well.40 To a degree, additional interest from these families can benefit two-way dual immersion programs. After all, these programs are built around linguistic balance, where half of the students are native English-speakers. They require native speakers of English and the partner language, since this mix helps significantly increase students’ social exposure to each language. However, in many communities, charter schools do not have the ability to reserve seats for native speakers of the partner language (most commonly Spanish). In Washington, D.C., Delaware, California, Oregon, and elsewhere, the increasing popularity of two-way dual language immersion programs among English-dominant families means they are becoming less accessible to ELs and their multilingual families.41

In communities with shifting student demographics, open enrollment lotteries can also undermine particular school models, especially those designed around linguistic diversity.

Allowing dual language immersion charter schools to weight their enrollments to serve more ELs would help them ensure that they reach their target population. Some states, such as New York, permit charters to give extra weight to EL students in their lotteries.42 As a result of a 2014 change by the Obama administration, charter schools supported with grants from the federal government’s Charter Schools Program can also pursue this strategy.43 Where state and local policies do not allow charter schools to choose to give ELs a leg up in their lotteries, policymakers should consider it.

So, knowing all of the challenges discussed above, how can policymakers ensure that multilingual families receive comprehensive, relevant, helpful information about their charter school options? How can they ensure that ELs have access to high-quality charter school options designed to serve them well?

Local education leaders should:

- Establish unified school lottery systems. These systems can make it easier for multilingual families to navigate their various charter school options. Ideally, unified lotteries should capture the full range of schools—both traditional public and charters—serving the community. With translation support, this may help multilingual families navigate unfamiliar school enrollment processes.

- Provide charters with the resources and capacity necessary to translate the written materials describing choice systems for families into all the languages in use in their community. This will help multilingual families get over the most basic hurdles preventing them from engaging as informed participants in open enrollment systems. In interviews, education stakeholders and immigrant advocates in New Orleans, New York City, the District of Columbia, and other communities frequently noted that basic translation of information about school choice systems is an obstacle for their work.44

- Make “language line” translation services available to charter schools and community organizers working to help multilingual families navigate school enrollment lottery systems. These systems provide on-demand oral translation services over the phone. While district schools typically have automatic access to these support services, charter schools frequently do not. In communities such as New York City, however, districts and charters are working together to ensure that all multilingual families can access these resources as they engage with their children’s schools, whether those are traditional public schools or charters.45

- Engage community organizations working with and advocating for immigrant communities. Many of these organizations have the cultural knowledge and linguistic competencies to help multilingual families access information about charter school options. These organizations are also likely to have a more sophisticated understanding of social networks within immigrant and multilingual communities than many policymakers and charter leaders do.46 If engaged respectfully and intentionally, they can use this knowledge to help ensure that charter schools’ recruitment efforts are effective. Organizations such as EdNavigator work directly with families in New Orleans and Boston to help them navigate school choice lotteries and enrollment processes, and provide additional school–family engagement support once children start school.47 To accommodate multilingual families, EdNavigator hires staff with multilingual and multicultural competencies. “Our priority is always to make our families feel comfortable,” says founding partner David Keeling.48 One of these “navigators,” Ileana Ortiz, agrees: “If you want to engage with parents, you have to speak to them in their language. Literally.”49 These organizations can also help policymakers and administrators learn how they could tweak existing public education data sources to make them more useful for multilingual families.

- Conduct regular outreach to determine what information multilingual families find useful, and how they use it to make decisions. Local education leaders should be wary of assuming that existing public information on school performance—and attached translation services—are satisfying multilingual families’ needs as they navigate charter school choice systems. As such, they should regularly collect feedback on what these families say they want to know about charter schools when they are considering them as potential options.

- Provide community organizations with targeted data materials designed to inform multilingual families about their high-quality school options. A recent study of school choice in New York City found that providing middle-school students who speak a non-English language at home with targeted information about higher-performing high school options significantly changed their choices.50 Education leaders could work with multilingual community organizations to generate a list of charter schools with demonstrated success serving ELs.

- Allow charter schools to opt into giving EL students a weighted preference in their lotteries. Some charters have made ELs central to their educational models. These schools should be able to tilt their enrollments to serve higher numbers of ELs. This could help two-way dual language immersion charter schools maintain the linguistically integrated student enrollment that their model is built to serve. This is also a common practice when traditional district schools establish “newcomer academies” to serve older ELs, as well as in other school models built around serving ELs’ linguistic development. Local leaders could also consider allowing charter schools to offer separate lotteries for native English speakers and native speakers of the other language used in instruction. However, charters in some places, such as Washington, D.C. and Arizona, are prevented from taking these steps.51 Dual language immersion charter leaders in Washington, D.C., Florida, and other communities report that they have struggled to navigate local prohibitions on EL lottery weighting as well as pressure from local English-dominant families interested in enrolling their children in these schools.52

- Provide transportation resources that help charter schools integrate their dual language immersion programs. As neighborhood and community demographics shift around dual language immersion programs, it can be difficult for schools—charter or traditional public—to maintain linguistic integration.53 Dedicated transportation supports—funding guided by public strategic plans that signal local commitment to linguistic equity—can help to ensure that two-way dual language immersion programs do not gentrify into one-way dual immersion programs exclusively for privileged, English-dominant families.

- Include EL enrollment in charter school audits. Local education officials—particularly charter school authorizers—should keep close tabs on EL enrollment in area charter schools. In particular, they should consider including EL testing, enrollment, and family engagement policies in school audits. This can begin with oversight to ensure that charters are in compliance with all applicable civil rights rules, but should also extend to recommendations regarding best practices for engaging multilingual families.

State education leaders should:

- Translate, monitor, and curate statewide education databases. State education agencies collect and publish significant amounts of data on schools. They should ensure that these databases are translated and the data themselves are presented in ways that serve multilingual families’ needs. The more information these families have about schools and how they serve ELs, the better decisions they will be able to make for their children. State education leaders should make it easy to isolate EL subgroup performance at a particular school and to compare it to EL performance at other schools and across the district and state.

- Track charter school enrollment trends. State education agencies should track EL enrollment trends in their state’s charter schools. They should look to see whether ELs are accessing their communities’ charter sector in proportion to their share of local students. Where there are EL enrollment gaps, state leaders should analyze EL achievement data for these communities and engage with EL-advocacy organizations to explore reasons for any discouraging—or encouraging—results.

- Allow charter schools to opt into providing EL students with weighted preference in their enrollment lotteries. This would allow local educators to give charter schools this opportunity, as recommended above.

Federal education leaders should:

- Provide competitive grants to help schools—traditional public and charter alike—interested in launching linguistically integrated dual language immersion programs. These programs are difficult to design and launch. Federal support could help build bilingual teacher pipelines, design new multilingual tests and curricula, and establish new dual language immersion programs. This would amount to a revival of the Bilingual Education Act (BEA). The BEA provided federal support for bilingual educational infrastructure from 1968 to 2001.54 This resuscitation would also build on existing grant programs within the Department of Education’s Office of English Language Acquisition.

- Require that Charter School Program grantees using federal funding to expand dual language immersion programming explain how these new multilingual campuses will be equitably accessible to English-learning students. As dual language immersion schools continue to rise in popularity with English-dominant families, it is critical that education leaders protect ELs’ access. Federal grants to create new dual language programs or expand current ones should make linguistic integration a priority.

Using the Flexibility in Charter School Models to Benefit English Learners

Shifting international and domestic migration patterns have brought large numbers of newcomer English-learning students to many U.S. communities. Charter schools’ flexibility gives them significant room to design schools with ELs in mind. In most cases, charter schools can tailor their schedules, curricula, and hiring to build coherent instructional programming that works for these students. At New York City’s Amber Charter School–East Harlem, for example, administrator Stephanie Nieves is grateful for “the flexibility in being able to adapt our curriculum and our approach with the [EL] students that we have, year to year. . . . [We can] say, ‘what is the need and how can we meet it,’ versus ‘this is the curriculum and this is what we stand by and that’s all we have.’”55

Shifting international and domestic migration patterns have brought large numbers of newcomer English-learning students to many U.S. communities. Charter schools’ flexibility gives them significant room to design schools with ELs in mind.

There are countless ways to use charter flexibility well. Different charter schools with different resources for serving different groups of ELs with different linguistic profiles in different communities will find different ways to design their campuses. For instance, Washington, D.C.’s Center City Public Charter Schools network has built a group of campuses with a strong focus on using data to provide targeted instruction to simultaneously advance ELs’ linguistic and academic development. At Center City campuses, this includes individualized English acquisition plans and expansive afterschool programming for ELs.56

Minneapolis’ Hiawatha Academies have made social justice and recognition of students’ cultural identities central to their EL-rich schools’ instructional models.57 “I take pride in talking about the idea that elevating this conversation in K–12 is deeply tied to the success in terms of a long-term view of success,” says former Hiawatha executive director Eli Kramer. “[We] unapologetically embrace the idea that a kid will be better set up for success in their life and in college if they are prepared from an identity perspective, to have a positive self-image, positive association with who they are and where they come from, their native language.”58 DeKalb PATH Academy, an immigrant-founded Atlanta charter school, has built its instructional and behavior management models around the values of the families it serves.59 The school’s “traditional values [are] cultural in the refugee and immigrant community,” says DeKalb PATH principal and CEO Crystal Felix-Clarke, “School is like the bridge to solidifying your status socioeconomically in this country.”60

In cases where newcomer students are older and/or have had limited or interrupted formal education, it can be helpful to establish Newcomer Academies built around their unique needs and situations. In cases where these students are young, it can be helpful to establish dual-generation schools that help children acclimate to U.S. schools while also supporting their families’ health and caregivers’ careers. In Washington, D.C., Briya Public Charter School brings together various public and philanthropic funding streams to run high-quality pre-K programming alongside health, dental, adult education, parent coaching, and English language classes for families.61 Decatur, Georgia’s International Community School (ICS) has dovetailed its instructional mission with local community organizations serving the needs of its many refugee families. ICS leaders have also used their charter flexibility to organize their school around the International Baccalaureate curriculum—and to offer multilingual programming to all students. School leaders say that this makes “everyone a language learner.”62

Similarly, many charters run two-way dual language immersion programs. These schools offer academic instruction in two languages and aim to enroll roughly equal proportions of students who are native speakers of English and native speakers of the “partner,” non-English language. This format allows EL students to access academic content in their home language while continuing to develop their linguistic skills in that language and English. It provides students of all linguistic backgrounds with the opportunity to be immersed in multilingual academic instruction. Perhaps more importantly, the presence of roughly equal numbers of peers who speak English or the program’s partner language as native speakers provides all students with a multilingual sociocultural environment. Research suggests that this balanced, linguistically integrated model is optimal for EL students and native English-speaking students alike.63

The presence of roughly equal numbers of peers who speak English or the program’s partner language as native speakers provides all students with a multilingual sociocultural environment.

Charter flexibility can make these programs easier to launch. Language immersion charter schools in Hawaii have used their autonomy to establish linguistically and culturally relevant campuses to help resuscitate the Hawaiian language. These schools are “community-designed and -controlled and reflect, respect, and embrace Hawaiian cultural values, philosophies and ideologies. . . . [They use] the national charter school movement as a vehicle to provide viable choices in education at the community level.”64 Similarly, charter schools in Minnesota, California, Illinois, and other states across the country are providing multilingual families with opportunities to affirm and develop their linguistic and cultural traditions.65

Local education leaders routinely cite the difficulty of finding credentialed bilingual teachers as the primary reason that they cannot offer dual language immersion programming or other multilingual instruction programs. While credentialed bilingual teachers are in short supply in many states, charter schools often have flexibility to staff classrooms with native speakers of non-English languages who may not have completed all of their state’s requirements for receiving a teaching license.66 This can help charter schools to expand access to multilingual instruction more easily than traditional public schools.67

The expansion of charter dual language immersion programs can support equitable access to multilingual instruction for ELs while also diversifying the U.S. teaching force. Research suggests that many teacher licensure systems are not effective systems for ensuring that license-holders deliver high-quality instruction, but many aspects of these systems are effective at preventing linguistically diverse, non-native speakers of English from becoming teachers. In some cases, teacher-candidates have most—or all—required credentials to become fully certified teachers, but struggle to pass their states’ teacher licensure exams in English. Charter schools can provide candidates like these with opportunities to use their linguistic abilities to expand access to dual immersion programs that help ELs succeed.

Once ELs are enrolled in these schools, it is important that they receive aligned educational services that support their linguistic and academic development. Rapid switches in instructional models can disrupt these processes—moving from balanced multilingual instruction to English immersion and then back, for instance. ELs benefit when language services and supports are scaffolded across multiple years of school. The bulk of ELs are native-born U.S. citizens, which means that they first arrive in U.S. schools in pre-K or kindergarten.68 Given that most research suggests that it takes an average of five to seven years for ELs to reach full academic English proficiency, alignment and continuity of language services should be a priority at least into middle school.69 As such, charter schools should be permitted to establish feeder patterns linking pre-K programs with elementary, middle, and high schools as needed.

In addition, charters’ flexibility sometimes comes at the cost of being able to fully participate in statewide education initiatives, including early education programs. These programs, most notably states’ public pre-K investments, merit special mention because research routinely finds that English learning students uniquely benefit from enrolling in them.70 A 2015 Bellwether Education Partners study found a range of state policy barriers preventing charter schools from providing pre-K programs. Specifically, they cited states’ pre-K funding structures, compliance and oversight metrics, and program objectives targeting specific student subgroups (which are often prohibited for consideration in charter admissions and enrollment policies).71

With the above examples in mind, how can policymakers ensure that charter schools use their notable flexibility to design schools that serve ELs well?

Local education leaders should:

- Utilize charter schools to launch multilingual campuses. Charter schools have significant flexibility from curricular mandates and teacher licensure rules that can slow or stop districts from launching high-quality dual language immersion programs. Local policymakers can use charter schools to launch more of these programs, which research suggests are the best instructional model for supporting ELs’ linguistic and academic development.

- Permit charter schools to organize feeder patterns linking elementary, middle, and high schools. This will help charter educators align EL services and supports throughout English-learning students’ preK–12 years. For ELs enrolled in a dual language immersion program or a scaffolded English language development program, this continuity is critical for their linguistic and academic development.

State education leaders should:

- Grant charter schools meaningful flexibility within teacher licensure and certification rules in order to support the hiring of promising, linguistically diverse teacher candidates. This will ensure that charter schools can take advantage of their school-level autonomy to design and implement innovative instructional models, like two-way dual language immersion programs, that are uniquely beneficial for EL students. Given persistent shortages in the number of bilingual teachers, this is a particularly valuable aspect of charter flexibility.

- Launch competitive grant programs to encourage public schools—charters and traditional public schools alike—to launch more two-way dual language immersion programming. Research suggests that dual language immersion programming is particularly effective for EL students. These programs help ELs learn English, develop proficiency in their native languages, and develop academically. At their best, dual language immersion programs can be a force for integration across multiple lines of student difference—linguistic, racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic. Charter schools’ flexibility on staffing, curricula, and scheduling makes them uniquely well-suited to develop and launch dual language immersion programs.

- Ensure charters have full, meaningful access to public early education funding. Public pre-K programs are generally powerful levers supporting young ELs’ linguistic and academic development. In many states, however, these programs have been designed outside of public education systems, or in ways that make it difficult for charter schools to receive funding. It can be difficult to make these funding streams—which frequently come with significant regulatory oversight—compatible with charter schools’ flexibility. State policymakers should explore ways to modify their early education oversight and accountability mechanisms so that charter participation in statewide early education programs will not present them with undue regulatory burdens that would undermine the autonomy that distinguishes them from traditional public schools. Of course, these modifications will vary significantly by state and program, and should be cautiously undertaken so that children’s health and safety are still protected. In the same way, charter leaders eager to receive public pre-K funding should be prepared to engage in intentional thinking about ensuring that their early education classrooms are developmentally appropriate; submitting to reasonable quality regulations and preK-specific accountability is a way to demonstrate good faith participation in these programs.

Federal education leaders should:

- Expand the dissemination of funding under the federal Charter Schools Program to encourage replication and scaling of effective charter practices for supporting ELs’ linguistic and academic development. Federal grant programs could support local and state efforts to support charter collaborations with new EL-focused competitive grant funding. This program could span a range of strategies and practices that work with ELs, but should pay special attention to charter experiments around staffing and implementing multilingual instructional programs.

Improving Charter School Accountability Regarding English Learners

Charter schools are subject to the same federal EL accountability regulations as traditional public schools. They must administer the same federally mandated academic assessments and the same English language proficiency assessments for tracking ELs’ English acquisition progress. They are also subject to their states’ accountability rating systems—which include ELs’ progress towards full English proficiency.72 Since challenges with federal EL accountability systems affect all public schools in the United States, it may be helpful to consider these in general terms. EL accountability in the United States has largely been structured around generic models for subgroup accountability. Students are regularly tested in academic subjects and English proficiency to gauge their progress. Schools where ELs underperform over time are then subjected to various pressures and sanctions.

But this accountability model is complicated by ELs’ linguistic profiles, which intersect with academic development as measured on standardized assessments in complex ways. Children enter into and pass out of the EL subgroup as they reach full English proficiency. This fluidity is unusual amongst student subgroups. While students’ acquisition of English is a key goal, it complicates efforts to track schools’ impacts on ELs’ academic trajectories. Research suggests that ELs’ academic performance improves as they approach full academic English proficiency. But, given the structure of federal EL accountability systems, this often makes the academic performance of the EL subgroup look weak. Given that No Child Left Behind (NCLB) defined ELs in part as students whose language profiles prevent them from demonstrating their academic abilities on English-language math and reading assessments, this accountability system more or less enshrined a permanent EL/non-EL achievement gap in federal law. Students were identified as ELs partly because their levels of English proficiency were such that they led to low academic scores. Then, when these students reached full English proficiency (and their academic scores rose), they would be reclassified from the EL group.73

While students’ acquisition of English is a key goal, it complicates efforts to track schools’ impacts on ELs’ academic trajectories.

The Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) tried to address this by letting states count former ELs’ academic scores as if they were still ELs for up to four years. This gives schools credit for former ELs’ academic performance even after they reach full proficiency in English. While this helps solve NCLB’s accountability problem, it also presents additional concerns. While including former ELs in accountability measurements of a school’s EL subgroup performance will raise the school’s academic performance for ELs, this runs the risk of obscuring the performance of current ELs. That is, if a school’s former ELs are performing well on math and literacy assessments, but current ELs are making no progress, combining the two groups’ performance for accountability may obscure real concerns about how current ELs are doing.

ESSA also moved the federal government’s primary EL accountability systems from the Elementary and Secondary Education Act’s Title III to Title I. This sought to focus accountability at the school level, not the district level. With more than $15 billion in annual funding (as of 2018), Title I is the federal government’s core K–12 education funding stream.74 This makes Title I requirements a central focus for state and local policymakers implementing ESSA.

When lawmakers moved federal EL accountability to ESSA’s Title I, they aimed to ensure that more ELs would have their academic and linguistic progress tracked under federal EL accountability. But it appears to risk the opposite, since federal data and privacy regulations (“n-size” rules) exempt schools with small EL subgroups from federal accountability calculations. Imagine that a state determines that federal accountability provisions kick in when there are more than ten ELs present in a particular place. Where the state calculates the size of the EL subgroup matters. Since districts generally contain multiple school campuses, they are more likely than individual school campuses to enroll more than ten ELs. In other words, the number of students in schools with enough ELs to be counted in ESSA’s new accountability systems is smaller than the number of students in districts with enough ELs to be counted in district-level accountability systems. The problem appears to be widespread—an analysis of several states indicates that ESSA’s change will hide the performance of thousands of ELs from public accountability systems.75

Both of these changes apply to all public schools, including charters. It bears noting that there are reasons to be skeptical about the overall efficacy of the details of federal accountability systems when it comes to improving educational opportunities for ELs. A 2012 study of federal EL accountability found that state and district officials were often unclear about federal objectives for English learners. It also found that leaders at these levels lacked the staff and resources to use accountability systems for genuine improvement efforts, instead of simply for basic compliance.76 The report characterized federal EL funding as “relatively small [and] supplementary,” and noted that this gave it “limited potency.”77

Nonetheless, these systems do capture the attention of administrators, educators, and policymakers in school districts and state education agencies.78 The 2012 report also concluded that, notwithstanding its limitations, federal EL accountability under NCLB “leveraged notable state and district activities in the areas of standards, assessments, accountability, and data systems over the past decade.”79 As such, accountability policies should be structured in ways that will measure EL progress in as many schools as possible.

Beyond compliance with the federal government’s regulatory baselines, however, state and local leaders have considerable room to develop nuanced, meaningful EL accountability metrics and systems. In exchange for flexibility on the design and conduct of various school-level processes, charter schools are supposed to commit to sharp outcomes-based accountability in a contract (that is, their “charter”) with the authorizer that permits them to launch and operate.

The school-level autonomy that charter schools have carries costs.

The school-level autonomy that charter schools have carries costs. While they can tailor their models around EL students, this autonomy generally means they must work outside of most systemic school district supports. That is, they are free from districtwide mandates that might not always serve ELs well, but they also do not benefit from the economies of scale that come from large central office administrative supports. In general, each charter campus by itself must handle compliance with local, state, and federal EL rules.

In response, district and charter leaders might consider looking for creative ways to incorporate charter schools into districts’ EL data systems. In return for systemic district supports, charters could expand collaboration efforts. District–charter collaboration takes different forms in different communities across the country. In Washington, D.C., they involve a variety of formal and informal mechanisms for swapping innovative pedagogical and educational ideas. They also include specific policy coordination, such as the local effort to bring most district and charter schools into MySchoolDC, the city’s common school enrollment lottery.80 New York City’s District–Charter Collaborative, by contrast, builds themed “learning communities” where charter and district school leaders can discuss common challenges and brainstorm solutions.81

How can policymakers ensure that charter schools are held accountable for ELs’ progress in ways that reflect these students’ unique linguistic and academic trajectories?

Local education leaders should:

- Use charter authorizers’ authority to establish EL-specific charter accountability metrics. This would allow local authorizers to experiment with new ways of measuring ELs’ linguistic development and academic performance over time. Given that research suggests that ELs’ age of first exposure to English has an impact on their English language acquisition trajectories, authorizers could consider establishing different English acquisition benchmarks for ELs who arrive in U.S. schools in pre-K or kindergarten than for ELs who arrive in U.S. schools in middle school.82

- Facilitate operations collaboration and data sharing between charter schools and/or between charters and school districts. Charter schools can retain the school-level autonomy that helps them serve ELs well, while also working together to streamline important data collection and compliance responsibilities. Partnerships between charters or with districts can help provide individual campuses with logistical support that will help them comply with baseline EL education and civil rights regulations. Coordination on these efforts can also support data sharing agreements that will make it easier for local education leaders—in charters and districts alike—to track EL students’ linguistic and academic progress over time (even if they should move between campuses).

- Facilitate educational collaboration between charter schools and/or between charter and school districts. Charter schools use their school-level autonomy to experiment with promising pedagogies for serving ELs. When charters discover pedagogies that work for ELs in their community, local education leaders should seek to replicate these models in other schools, charters and district schools alike. For instance, in 2017, Washington, D.C. used federal dissemination grant funding to provide Center City Public Charter Schools with a grant for replicating its afterschool program for ELs in a traditional district school, H.D. Cooke Elementary School.83

State education leaders should:

- Calculate EL performance across three years for the purposes of accountability. This will ensure that more charter schools that serve small numbers of ELs (beneath their state’s minimum n-size) are captured in state and federal accountability systems. For instance, if a state sets a minimum n-size of 10 for accountability purposes, a school with four English learners could still be rated in EL accountability, since the three years of EL performance data would amount to 12 total data points.

- Explore ways to improve EL-specific charter school accountability metrics. Many local, state, and federal EL accountability systems are ill-suited to providing schools with goals and consequence that responsibly track ELs’ diverse linguistic and academic developmental trajectories. As schools that are primarily held accountable for their outcomes, charters are uniquely well-positioned for policy experiments in this regard. State policymakers should consider creating ways that charter schools could measure their progress advancing ELs’ linguistic and academic development. This could take several forms. State leaders could mandate that authorizers use particular EL metrics with new charter schools—requiring that all new contracts set EL English acquisition growth expectations, for instance, or providing a specific timeline for ELs to reach full English proficiency. Or they could require school leaders applying for a charter to develop and submit their own EL metrics. For instance, schools could then propose language acquisition goals in English and in ELs’ home languages, for multilingual campuses.84

- Provide targeted grant funding to support collaboration between charter schools and/or between charters and school districts. While charter schools’ independence is their primary advantage, it can sometimes make it difficult for them to manage compliance with EL regulations that require collecting and analyzing EL students’ achievement data. State education policymakers can explore ways to allow charter schools to pool resources and expertise to streamline these processes with other charter schools or with local school districts.

Federal education leaders should:

- Reinstate district-level accountability alongside school-level accountability. ESSA moved EL accountability to schools, while NCLB focused EL accountability on districts. This change from examining districts to examining schools aimed to ensure that more schools would have to focus on serving ELs. However, given that this shift could unintentionally remove thousands of ELs from oversight under accountability systems, Congress should consider requiring states to hold both districts and schools accountable for ELs’ English acquisition and academic progress.

Conclusion

Many educators and policymakers are searching for ways to serve their communities’—and the country’s—increasing linguistic diversity. Charter schools can be a powerful tool in this process. Their flexibility around staffing, scheduling, and curricular choices gives them significant potential for designing coherent school models to serve ELs well. High-quality charter schools that enroll students through open lotteries can be a powerful force for educational equity in communities where ELs’ families would otherwise only have access to the schools they can purchase through the real estate market.

But these advantages do not inevitably translate into improved opportunities for EL students. Charters can also use their school-level autonomy to design schools that ignore or marginalize ELs’ needs. Multilingual families of ELs may struggle to engage with and/or navigate charter enrollment systems. Charters’ freedom from school district bureaucracy also amounts to separation from school district supports and efficiencies of scale when it comes to analyzing EL achievement data and/or complying with accountability regulations.

Fortunately, the choice between these two paths—charters’ promise and charters’ potential failures—does not rely on a random toss of fate. Policymakers at all levels can build systems that support equitable EL access to, and performance in, charter schools.

Acknowledgments

This project has benefitted from hundreds of conversations with educators, researchers, and policymakers over the past several years. Ashley Simpson Baird, Robin Chait, Ruby Takanishi, Maggie S. Marcus, Rohini Ramnath, Scott Pearson, Lea Crusey, and Carolyn Sattin-Bajaj provided notable insights, advice, and/or feedback. Several Century Foundation colleagues also contributed helpful ideas, particularly Richard Kahlenberg and Halley Potter. Finally, this project would not have launched or come to fruition without the support of the Walton Family Foundation. The argument contained here, however, is entirely the creation and responsibility of the author.

Notes

- “Children Who Speak a Language Other Than English at Home,” Census 2002–2017, American Community Survey, accessed October 4, 2018, via Kids Count Data Center, https://datacenter.kidscount.org/data/tables/81-children-who-speak-a-language-other-than-english-at-home?loc=1&loct=1#detailed/1/any/false/870,573,869,36,868,867,133,38,35,11/any/396,397.

- “Table 204.20, English language learner (ELL) students enrolled in public elementary and secondary schools, by state: Selected years, fall 2000 through fall 2015,” Digest of Education Statistics (Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, 2018), accessed October 4, 2018, https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d17/tables/dt17_204.20.asp.

- “Table 204.20, English language learner (ELL) students enrolled in public elementary and secondary schools, by state: Selected years, fall 2000 through fall 2015,” Digest of Education Statistics (Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, 2018), accessed October 4, 2018, https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d17/tables/dt17_204.20.asp.

- “Table 216.20, Number and enrollment of public elementary and secondary schools, by school level, type, and charter and magnet status: Selected years, 1990–91 through 2015–16,” Digest of Education Statistics (Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, 2018), accessed November 30, 2018, https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d17/tables/dt17_216.20.asp.

- Regardless of their generational proximity to the U.S. immigration experience, American families use myriad languages in myriad ways. For the purposes of this report, “multilingual families” refers to families that speak a non-English language at home. This may be their only home language, or it may be one of several languages (including English). This definition aims to capture the full range of families whose linguistic and cultural backgrounds may make it more difficult for them to navigate the institutional norms and English-dominant bureaucratic processes involved in public school enrollment. After all, these families often—but not always—include at least one parent who has recently immigrated to the United States. These families may or may not be linguistically isolated households, in which no adults speak English with a basic level of proficiency. Finally, children from these families may or may not be officially designated as English learners.

- For examples of how charter policies can differ across state lines—as well as discussion of the consequences of these differences, see: Halley Potter and Miriam Nunberg, Scoring States on Charter School Integration (New York: The Century Foundation, April 4, 2019), https://tcf.org/content/report/scoring-states-charter-school-integration/. See also the database accompanying the report at http://charterdiversity.org/ for more evidence of the diversity in states’ charter school policies.

- Donald J. Hernandez, Ruby Takanishi, Karen G. Marotz, “Life Circumstances and Public Policies for Young Children in Immigrant Families,” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 24, no. 4 (2009): 492–3, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2009.09.003; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Promoting the Educational Success of Children and Youth Learning English: Promising Futures, (Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2017), 74, https://doi.org/10.17226/24677. On the specific danger of treating multilingual families’ school choice preferences as uniform, see: Carolyn Sattin-Bajaj, Unaccompanied Minors: Immigrant Youth, School Choice, and the Pursuit of Equity (Cambridge: Harvard Education Press, 2014), 122: “Yet language barriers, background knowledge about New York City schools, and unequal resources only partially explain parents’ engagement in passive versus strategic high school choice with (or on behalf of) their eighth-grade children. Instead, the variation observed can also be attributed to parents’ ideas about child-rearing, their views on the appropriate division of labor between parents and children, and to possession or lack of an effective institutional compass to negotiate the high school choice maze.”

- Todd Ziebarth, Measuring up to the Model: A Ranking of State Public Charter School Laws, 10th ed. (Washington, DC: National Alliance of Public Charter Schools, January 2019), https://www.publiccharters.org/sites/default/files/documents/2019-01/07_rd3_model_law_ranking_report.pdf.

- “Charter School FAQs,” National Alliance for Public Charter Schools, accessed December 19, 2018, https://www.publiccharters.org/about-charter-schools/charter-school-faq.

- Cf. Halley Potter and Miriam Nunberg, Scoring States on Charter School Integration (New York: The Century Foundation, April 4, 2019), https://tcf.org/content/report/scoring-states-charter-school-integration/.

- Edward Cremata, Devora Davis, Kathleen Dickey, Kristina Lawyer, Yohannes Negassi, Margaret Raymond, and James L. Woodworth, National Charter School Study 2013 (Stanford, CA: Center for Research on Education Outcomes, 2013), 52–57, https://credo.stanford.edu/documents/NCSS%202013%20Final%20Draft.pdf.

- Edward Cremata, Devora Davis, Kathleen Dickey, Kristina Lawyer, Yohannes Negassi, Margaret Raymond, and James L. Woodworth, National Charter School Study 2013 (Stanford, CA: Center for Research on Education Outcomes, 2013), 77, https://credo.stanford.edu/documents/NCSS%202013%20Final%20Draft.pdf.

- Edward Cremata, Devora Davis, Kathleen Dickey, Kristina Lawyer, Yohannes Negassi, Margaret Raymond, and James L. Woodworth, National Charter School Study 2013 (Stanford, CA: Center for Research on Education Outcomes, 2013), 72, https://credo.stanford.edu/documents/NCSS%202013%20Final%20Draft.pdf.

- CREDO, Charter School Performance in Texas (Stanford, CA: Center for Research on Education Outcomes, August 2017), 30, https://credo.stanford.edu/pdfs/Texas%202017.pdf.

- Richard D. Kahlenberg and Halley Potter, “The Original Charter School Vision,” New York Times, August 30, 2014, https://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/31/opinion/sunday/albert-shanker-the-original-charter-school-visionary.html; Neerav Kingsland, “What If Everything You Believe About Education Is Wrong?” blog, January 18, 2017, https://relinquishment.org/2017/01/18/what-if-everything-you-believe-about-education-is-wrong/.

- Erin Roth, Abel McDaniels, Catherine Brown, and Neil Campbell, “The Progressive Case for Charter Schools,” Center for American Progress, October 24, 2017, https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/education-k-12/news/2017/10/24/440833/the-progressive-case-for-charter-schools/; Conor Williams, “The Perks of a Play-in-the-Mud Educational Philosophy,” The Atlantic, April 26, 2018, https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2018/04/early-childhood-outdoor-education/558959/.

- John Chubb and Terry Moe, Politics, Markets, and America’s Schools (Washington, DC: Brookings, 1990).

- Carolyn Sattin-Bajaj, Unaccompanied Minors: Immigrant Youth, School Choice, and the Pursuit of Equity (Cambridge: Harvard Education Press, 2014), 147.

- Carolyn Sattin-Bajaj, Unaccompanied Minors: Immigrant Youth, School Choice, and the Pursuit of Equity (Cambridge: Harvard Education Press, 2014), 148: “The skills and strategies that can be honed through the process of choosing high schools in New York City—namely, conducting research, analyzing school performance and other data, weighing options, and ranking preferences—are in fact applicable to many other personal and professional experiences.” See also Sattin-Bajaj, 165–8.

- GeorgiaCAN’s Steven Quinn describes the (emblematic) situation with Georgia charter schools this way: “A lot of it too, to be honest with you . . . is that there’s not a lot of information given to these parents. I think these schools exist, but they’re not reaching out to these students, with the exception of ICS . . . they’re not providing documents in their languages, and it’s not very clear what the school is. That’s a big piece of the puzzle. Down the road, that’s a conversation that needs to start.” Interview with author, June 9, 2017.

- Marcus Winters, “Why the Gap? English Language Learners and New York City Charter Schools?” (New York: Center for State and Local Leadership at the Manhattan Institute, 2014), https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED564925.pdf.

- Marcus Winters, “Why the Gap? English Language Learners and New York City Charter Schools?” (New York: Center for State and Local Leadership at the Manhattan Institute, 2014), 2, https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED564925.pdf.

- A.Y. Fred Ramirez, “Dismay and Disappointment: Parental Involvement of Latino Immigrant Parents,” Urban Review 35, no. 2 (June 2003): 98, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1023/A:1023705511946; Madeline Mavrogordato and Marc Stein, “Accessing Choice: A Mixed-Methods Examination of How Latino Parents Engage in the Educational Marketplace,” Urban Education 51, no. 9 (November 2016): 1031–1064, https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085914553674; Guadalupe Valdés, Con Respeto: Bridging the Distances between Culturally Diverse Families and Schools—An Ethnographic Portrait (New York, NY: Teachers College Press, 1996).

- Author interviews with charter school leaders, June 19, 2018. Author interviews with charter school leaders, October 6, 2016. Email exchange, February 26, 2019. At the request of the administrators interviewed, I have allowed them to remain anonymous for the purpose of this report.

- Interview with Sashemani Elliott, January 30, 2019.

- Carolyn Sattin-Bajaj, Unaccompanied Minors: Immigrant Youth, School Choice, and the Pursuit of Equity (Cambridge: Harvard Education Press, 2014), 117; Concha Delgado-Gaitan, “School Matters in the Mexican-American Home: Socializing Children to Education,” American Educational Research Journal 29, no. 3 (1992): 495–513, https://www.jstor.org/stable/1163255?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents; Guadalupe Valdes, Con Respeto: Bridging the Distance between Culturally Diverse Families and Schools: An Ethnographic Portrait (New York: Teachers College Press, 1996).

- “School Choice and English Learners in Houston,” Kinder Institute, Rice University, November 6, 2017, accessed January 10, 2017, https://kinder.rice.edu/2017/11/06/school-choice-and-english-learners-in-houston.

- Ernesto Castañeda, A Place to Call Home: Immigrant Exclusion and Urban Belonging in New York, Paris, and Barcelona (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2018); Madeline Mavrogordato and Marc Stein, “Accessing Choice: A Mixed-Methods Examination of How Latino Parents Engage in the Educational Marketplace,” Urban Education 51, no. 9 (November 2016): 1039, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0042085914553674.