On May 6, 2018, Lebanon will be holding its first competitive parliamentary elections in almost a decade. In that interim, the Lebanese Parliament, propped up by a political system based on clientelism and patronage and internationally acknowledged as compromised, has unconstitutionally extended its term three times. A new electoral law, known as the “Adwan law,”1 was passed into law in the summer of 2017, and appears to instate proportional representation in government for the first time since the country’s independence in 1943.2 But what sort of change does this law, drafted in a rush and out of the public eye, and after years of procrastination, bargaining, and political maneuvering, actually guarantee?

As it turns out, very little. Not only does it preserve the existing power relations that have underlaid all Lebanese elections thus far: it also, by design, encourages sectarian political campaigning, and therefore even greater sectarian division.3 Parliamentary seats are still allocated according to a sectarian apportionment, and the new election law adopts a redistricting mechanism that is based on a sectarian demographic distribution where various political bosses have deep patronage networks.

If the system has hardly changed, the landscape of political competition within it has. Opposition to the status quo has been growing over the past few years, and many non-aligned, reformist political groupings, secular political parties, and aspiring individuals believe they at least have a chance to win a seat at the table. They realize that the current Parliament has pushed its luck, and hope that the epic failures of the ruling elite will encourage voters to opt for new faces. Many also feel that they have a responsibility to take matters into their own hands, and channel the sentiment of the 2015 protest movements and the 2016 municipality elections.4

While in part galvanized by the obvious false promise of the new electoral law, these challenger groups are still struggling to find their place within the political order. While many of them come from the new emboldened generation of activists and candidates who are willing to speak truth to power, they do not constitute a unified or robust opposition, and their political outlooks, and electoral strategies, diverge on many levels.5

On the other side of the faceoff, Lebanon’s political bosses, although in disagreement on almost everything else, do share one goal: to fend off any meaningful effort at systemic reform. These elites, known as the “Zuama,” no longer fear challenges from self-defined “civil society” challenger groups, whose soft rhetoric and criticism they have not only washed right off, but have even readily co-opted into their own political platforms. Even so, within limits, this year’s electoral battles will be frantic for the establishment, and the reliable tactics of sectarian campaigning will be their first choice. Challenger groups claim that they hope to counter those tactics, and in the process redefine what it means to do politics in the country—a test that has proven to be harder than they thought.

This exercise, however superficial, in electoral politics can be an opportunity for genuine reformers to learn how the Lebanese political machine works. But as these elections will show, the ranks of the genuine will be slim, and any authentic project of political opposition is certain to disintegrate by the end of the political process. Meanwhile, political bosses will agree to tighten patronage networks and further compartmentalize their share of spoils within the new political order, expand their personality cult projects, and censor or repress any legitimate opposition.

So no: the results of May 6 are not likely to make the political situation in Lebanon any less grim. But the political machine is indeed changing shape, and is poised to acquire a few new parts.

So no: the results of May 6 are not likely to make the political situation in Lebanon any less grim. But the political machine is indeed changing shape, and is poised to acquire a few new parts. This report seeks to offer a lay of the land as this process comes to fruition.

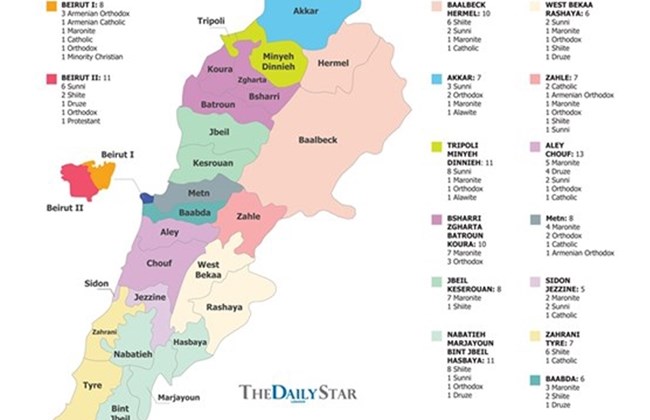

Under the new law, the country will be divided into fifteen major districts, and twenty-seven minor districts.6 The 128 members of Parliament are distributed across the minor districts based on an established sect-based quota for each of Lebanon’s eighteen “confessions”—or government-recognized religious group—and the demographic weight of each religious sect in each district.

While this new system of proportional representation technically replaces the long-standing majoritarian formula that preceded it—one which all but explicitly permitted party leaders and cadres to track, buy votes from,7 harass, and cheat voters—the difference is essentially cosmetic. Rather than a path out of sectarianism, as some touted it,8 the law further consolidates patronage politics and the rule of sectarian appeal. Voters can select one list from a pre-registered number of closed lists of allied candidates in their major district, but can optionally cast only one preferential vote for a candidate running in their minor district. Winning candidates from each list are not ranked based on the number of votes they receive in their major district, but by the percentage of preferential votes they receive in the minor constituency—most of which are based on homogenous constituencies loyal to this or that political boss.

This arrangement has lead to unorthodox and unusual electoral alliances that follow gerrymandered calculations.9 The various competing political machines work through what are known as “electoral keys,”10 local brokers who can secure votes of an entire kin community in exchange for services or “get out of jail free” cards for voters. Sami Atallah, executive director of the Lebanese Center for Policy Studies (LCPS), argues that voting, given these circumstances, becomes more of a social obligation than a public duty.11

Given the deep sectarian grooves already in place, most voters will cast their preferential vote for the candidate that comes from their own sect. Therefore, as analyst and blogger Ramez Dagher explains,12 the most outspokenly sectarian candidate on each list will receive their sect’s votes in their district—and whichever sect already holds the majority in a given district will come out on top. Even though the traditional rivalry between, for example, the Future Movement, led by prime minister Saad Hariri, and Hezbollah still stands, it does so only in form. Those old rivalries had at least a modicum of political content; under the new law, rivalry will not be based on constructive political debate at all.

Unsurprisingly, Lebanon’s political bosses are capitalizing on these superficial sectarian differences to stir people’s anxieties, making sure that neither moderates nor independents make it through to Parliament. These elites will have to restructure their shares, but ultimately won’t have to give up any of their political control. Dagher, who has brilliantly broken down how the law suits the bosses’ needs, explains that the Adwan Law, which carries the name of its creator, deputy leader of the Lebanese Forces (LF) party MP Georges Adwan, is an aggression on the idea of fair representation.13 Adwan, it should be known, literally translates to “aggression” in Arabic.

Electoral Behavior and Battles among Challengers

This year’s long-awaited elections are taking place in a very different political environment than did the 2009 parliamentary elections: the stark sectarian alliances that have dominated the political scene since the 2005 assassination of prime minister Rafic Hariri are no longer the epicenter of political debate, and public grievances and dissatisfaction with government corruption and ineptitude have reached an all-time high. The rise of anti-status-quo campaigns showcases the deep dissatisfaction of a disenfranchised Lebanese public that wants real solutions to the fundamental crises of a country where the state cannot provide social security, basic livelihood needs, or solvency.

Today, any challenger to the status quo is given by the mainstream media the label of “civil society’—a loaded term, one filled with optimism for a coalition that will speak for the people, and therefore one that can only disappoint. Newcomer groups have been heavily criticized for failing to create one unified electoral alliance across the main districts that can face off with the establishment lists. However, as fragmented and compartmentalized as these new groups and campaigns may be, together they are helping to cast the die for this new shape of Lebanese politics, and so must be examined closely. Naturally, the election law is a key determinant in these changes, but so is the electoral behavior of challengers.

Costs of Unity: Challenger Groups Criticize The LiWatani Alliance

After the protest movements of the 2015 garbage crisis,14 and the rising momentum of the ensuing political grassroots organizations that ran for the municipality elections in 2016, there were many that believed the political process in Lebanon was maturing.15 Key founders of those movements—academics, professionals, practitioners, and activists alike—said they were in it for the long haul; and surely enough, many decided to set up their own electoral machines to run for Parliament this year.

On January 19, 2018, eleven groups from the 2015 protest movements, including some organizations that had grown out of of the 2016 municipality elections, announced the formation of what they called LiWatani (For My Nation). After the initial launch, Wadih Al Asmar, a representative of the post-garbage-crisis protest organization #YouStink, told the Daily Star that LiWatani is a political alliance, and that “the goal is to unite the opposition forces that are not tied to parties of the state, nor sects, nor regional disputes.”16 While Al Asmar is correct about the common denominator—anti-status-quo politics—calling LiWatani an alliance is too generous: the loose coalition has never been able to agree on any of the thorniest and most pressing issues that face them, such as the personal status law, different understandings of the secular state, Hezbollah’s arms, and a sectarian identity that persists among Lebanon’s most disadvantaged groups. But LiWatani’s attempt to unite advocates of local political concerns with organizers that possess more nationally oriented anti-status-quo ambitions has proven so novel that the experiment has become the epicenter of the political debate among the so-called civil society groups. While many remain wary of this performance of unity with so much left unresolved underneath it, LiWatani-affiliated groups eventually managed to form allied lists under the title “Kilna Watani” (We are All the Nation) in nine districts and for sixty-six candidates.17

Pragmatism in the face of a shifting political structure is the source of the groups’ success, a pragmatism based on an understanding that to win seats, all challenger groups must unite at least superficially. Mohammad Shamseddine, a renowned research and elections specialist with International Information, says such groupings “are all protest movements and not political projects…because being the ‘other’ to the establishment can only take you so far.”18 The debates that unfolded in the wake of the LiWatani coalition’s formation have proven emblematic of the key strategic differences among anti-status-quo groups on the nature of electoral alliances versus that of political alliances, and the costs of picking one over the other.

The move became to ally with anyone who was not part of the establishment—and iron out the details later, if at all.

Most noteworthy of these coalition groups is LiBaladi (For My Country), a group of professionals and activists who were also founders and key members of Beirut Madinati. Beirut Madinati is a citizen’s movement that channeled and translated a protest sentiment into a serious reform project that shook the establishment elite during the 2016 municipality elections, and then decided to stick to its grassroots work. LiBaladi’s electoral program revolves around changing voter perceptions of the role of parliamentarians and the rule of law: elected representatives are to be seen as employees and defenders of the constitution, and not as patrons. Nayla Geagea, a Beirut Madinati co-founder, lawyer, and a LiBaladi candidate until only recently, admits that LiWatani is a necessary alliance, because “at this stage, we can not afford to divide up civil society groups, despite all their differences, because every new list is a seat for the establishment.”19 And so the argument goes like this: the patronage networks and street power of political bosses is far too deep and strong to resist without a united front, and voters will surely not place their trust in challengers if they are offered too many choices. So the move became to ally with anyone who was not part of the establishment—and iron out the details later, if at all.

Others, however, disagree with this logic, on matters of principle as well as strategy. Some believe that genuine reformers, such as the LiBaladi candidates and the #YouStink movement, compromised their political principles and vision for the sake of unity. One member of the coalition, the political party Sabaa (Seven), is a significant bone of contention. Formed in late 2016, Sabaa not a typical citizen’s movement: it was set up as a business model and not as a mode of political change. The party has succeeded in attracting some of Lebanon’s wealthiest and and most prominent media figures, and has raised a lot of concerns among independent reformers with regards to its financial transparency. In the eyes of long-struggling reformers, Sabaa is a hub for elites, stacking up figures that are friendly with the establishment.

How, then, has Sabaa won a place in LiWatani? In short, because of their plush marketing strategy. An introductory video to their campaign crowns Sabaa as the only hope for change, and their electoral program includes a service provision reform plan called “the happy citizen,” and a neoliberal economic plan called “the revolution”: together they lay out broad policies for better services, better employment, better livelihoods—better everything.20 These tactics, coupled with the company that the party keeps, have alienated a large number of supporters and activists that had previously worked with Beirut Madinati and would have considered aligning with LiBaladi.

In this way, the LiWatani coalition has pasted together numerous contradictory and uncomplimentary discourses and goals. Nowhere has this been more clear than in Beirut’s two electoral districts. In the first district, after arduous deliberations, LiWatani managed to form a unified list against two establishment lists. But even with its own internal decision-making body—a board of directors, and general assembly—LiWatani eventually had to resort to public opinion census to determine which candidates would step down to make room for others.21

Geagea, and Assad Thebian, the latter also a leading figure in the #YouStink movement, conceded their candidacy in the second district of Beirut a day before the door for list registration closed. After three months of negotiations, Geagea explains that there were far too many compromises that contradicted her political principles concerning what strategy was best suited for this highly sectarianized district. She also expressed her frustration towards the new election law, which was designed to cause fragmentation and pit individuals against one another, as well as limit candidates to a sectarian demographic distribution.22 In a Facebook post,23 Geagea announced, “my decision is due to incidents I have witnessed during the negotiation phase on whether we would participate in the elections, and later, during the list formation phase.” At a public debate at a café in Beirut, Geagea called the negotiations a “massacre” to politics and citizens’ needs, but emphasized that despite all that, anyone that challenges the establishment is worth considering. At that same debate, Thebian thought it unfair that their alliance would be so heavily criticized: “Sure, they do not all look like us one 100-percent, but of course we had to compromise for the sake of the promise.”24 However, for many, promises lost their substance due to these contradictory alliances.

The second district, colloquially known as the “Sunni Nerve,” is an electoral battleground. It is known to hold the strongest support base for the Sunni-representative Future Movement in Beirut, with more than 60 percent of the city’s Sunni voters.25 At one point, there were 117 registered candidates—an “election bazaar,” as Geagea called it.26 There are today nine registered lists, seven of which are considered “civil society” representative lists, including some which are part of wealthy and large Sunni families in Beirut, and two establishment lists. Anti-status-quo candidates disagree on how far they should be “anti-sectarian.” Many, such as Geagea, refused to compromise on such matters.

For Citizens in a State, a newcomer political party headed by previous labor minister Charbel Nahhas, all these groups are going about it the wrong way. Nahhas is a staunch critic not only of the sectarian system but also of all other challenger groups, who he views as politically compromised. For Nahhas, “there is the establishment, there is ‘civil society,’ and then there is us.” For him, the real issue is structural: for instance, public debt,27 the salary scale law,28 labor laws,29 and the new rent law.30 After being harshly questioned for his hardened position towards other reformers at a lecture at the Golden Tulip Hotel in Beirut in February, Nahhas shrugged, “Why is everyone obsessed with ‘civil society,’ with defining it, with seeing what it is connected to, how we can build it? I don’t even know what ‘it’ is. We are very satisfied without that title.”31

In the eyes of Citizens in a State, the real debate should be about the intricate networks of political power and financial interests that preserve the political boss system. A member of the party, Ahmad Al Assi, sighs at the idea of having to negotiate with so many groups: “it is impossible to reach any decision with that level of decentralization and lack of leadership.” Assi calls it a competition of egos, where “everybody wants to sit at the table, but the table cannot fit them all.”32 For Citizens in a State, this election is a “carnival,” but one that they have to participate in for the sake of extending their idea of a secular state that separates religion from state in all public and private matters: for them, the process is what counts, not the electoral win.

It’s refreshing that Citizens in a State do have an independent political organization with a common goal, a common project, and a shared set of means, but are also dismissive of ideas that do not take a structural approach to the country’s problems. Despite that, Citizens in a State know very well that creating more than one list under the title of ‘civil society’ would hurt everybody’s chances of success. “Our battle goes deep into the systemic problems; their [civil society groups’] battle is shallow,” explains Assi, “but there are battles whose course of action you just cannot escape, like elections.”33 Eventually, Citizens in a State agreed with LiWatani that they will not run in competing lists in the districts in which LiWatani is running and instead will have their candidates enlist in the “Kilna Watani” lists.

Hezbollah and the Ruling Elite

One thing that Lebanese activists and challenger groups do seem to agree on, though, is that in Lebanon, doing politics still means doing Hezbollah politics.34 The issue of Hezbollah’s arms—it’s the only political group in the country with its own military—came up in almost all of the interviews conducted for this report, and has been decisive in the divergences of strategy and goals among those seeking to alter the status quo. Aside from Sabaa, another group within LiWatani called Sah (Correct) involves individuals who were previously members of the Free Patriotic Movement (FPM), Lebanon’s leading Christian political party, but were kicked out over a disagreement concerning its new leadership. A representative of Sah, Ziad Abs, was key to drafting the Memorandum of Understanding between the FPM and Hezbollah in 2006. Thanks to Abs’s involvement, LiWatani has worked to circumvent the issue of Hezbollah’s militarized status; two articles in its political document state that the LiWatani alliance “respects the sovereignty of the state’s territory through a comprehensive political, social, economic, and defense strategy, and through the development of the capabilities of the army and its institutions.” Here, instead of openly calling out Hezbollah, the alliance’s political document opts to say very little at all. The two articles mention what all parties, including Hezbollah, already agree on: sovereignty and the army. Many would argue that Hezbollah protects territorial sovereignty by breaching state sovereignty, and its legitimacy partly depends on its public support of the central role of the army. Many say they did not want to centralize the Hezbollah issue because parliamentary politics are about more than that.

But for many others, avoiding the issue of Hezbollah’s arms shows a lack of political insight and clarity. One of the many lists in the second district is a list by the name “Kelna Beirut” (We Are All Beirut),35 a list which also includes previous members of Beirut Madinati, such as Ibrahim Mneimneh. Rida Mawla, who is working with Kilna Beirut, says they are more harmonious and clear-headed. To create something that people will rally over, “you have to get very specific about certain issues,” says Mawla, hinting at the list’s position towards Hezbollah’s arms. In his candidacy speech, which Mawla helped draft, Mneimneh, like many others, prioritizes the constitution and the state, and stresses that we should resist all forms of occupation, from the French mandate years, to today’s foreign tutelage, hinting at Iranian and Syrian tutelage, whose leaders support Hezbollah politically and economically.36

This distinction that Kelna Beirut hopes to make between itself and other challenger groups is, once again, ultimately superficial—merely a matter of branding. All these groups, from LiBaladi, to Kilna Beirut, to #YouStink, agree on one thing: to reinstate the civil state. But the notion of a “civil state” has become so vague and hollow that no constructive unity can come out of it.

All these groups…agree on one thing: to reinstate the civil state. But the notion of a ‘civil state’ has become so vague and hollow that no constructive unity can come out of it.

Most anti-status-quo candidates, in truth, don’t even particularly merit the label of “anti-status-quo”: without exception, they all fall back into a discourse for change that is inextricably attached to the behavior of the established elite, and their underlying defense strategies are determined purely in relation to the establishment: “We are as good as they are bad.”

This is not to undermine the seriousness and difficulty of the task at hand. Among themselves, Geagea and others know very well what they are up against, know that they have dim chances, and that there are certain constituencies they are just not ready to address. But that then means that they use their rhetoric of “vote for change” in full awareness that they’re presenting a false promise. Political change requires much more than a quick fix, and certainly much more than one electoral battle.

Political Cynicism: Challenger Groups Fail to Gain Public Trust

Cynicism is a Lebanese forte, and for good reason; but it’s easy to complain. The majority of Lebanese are indeed fed up with the constant bickering of the ruling elite, and there is a widespread desire for revenge against a political class that has failed to provide the bare minimum to a tired public. Many voters say they have a new sense of civic duty these days.37 But as Shamseddine puts it, laughing, “the Lebanese protest from the comfort of their homes.” Even when they say sectarianism is wrong, and might even be aware that their sectarian identities and misfortunes are shaped by the realities of the system, they continue to engage in sectarian behavior. Their immediate interests are tied to clientelist and patronage networks that govern their everyday lives. Similarly, many fear socially sanctioned behavior. Support for sectarian parties is also sustained through pressure from family, friends, party cadres, and religious communities. While it is clear that the various challenger groups merit criticism, and to some degree dismissal, popular pessimism often falls even beyond dismissal of individual actors and into dismissal of the entire project of reform.

There are 976 candidates registered for this year’s elections,38 and seventy-seven candidate lists,39 the highest number in all of Lebanon’s election history. And with such numbers, it is even harder to differentiate the genuine reformer from the political opportunist. If given too many choices, all of which, through pessimism’s lens, seem equally dismal, the Lebanese voter would then rather vote for what he knows, instead of having to put the effort into looking at the profile of every list and candidate and make an informed choice that seems to make no difference. For multiple reasons, challenger groups have lost the public’s trust.

In my conversations with voters, some feel challenger groups have let them down, whereas others believe these groups, though genuine, have very limited reach and resources. One voter, who is tired of hearing about a new group every day, said she would vote for the establishment’s list just to shock civil society groups and teach them a lesson so they would get organized once and for all—like a mother would with her child, she said. Shamseddine thinks the candidates have no discipline, vision, or unity: “I don’t see any seriousness: I am a candidate, I get on television, I put a billboard, and that is it.”40 He added that the protests that ensued after the 2015 garbage crisis led many to believe that these groups only know how to shout, and have nothing concrete to offer. At the height of the crisis, these groups, it is said, wasted the opportunity.

Shamseddine, who lumps all these groups into one category, believes they offer no concrete plan or program: “They do not have the desire or the ability to become an actual alternative,” he says dismissively. It would be unfair, however, to say that the challenger groups are not offering any alternatives at all. True, they don’t have the capacity, at the moment, to bring reforms to fruition. But in my conversations with many genuine reformers, the desire is most definitely there.

Another issue is cynicism about the role of Parliament. The Lebanese already know that Parliament does not legislate, as it should: MPs do not have any idea about socioeconomic policies or a comprehensive policy within their own party, but are simply there to do what they are told by the ruling elite.41 So the public knows that alternative candidates cannot really do much in Parliament even if they get in. Khalil Gebara, advisor to the minister of interior, said at an academic conference on political inclusion at Issam Fares Institute for Public Policy and International affairs (IFI) in Beirut, “if you get to the bottom of it, we know MPs are not decision makers and are not involved in making policies. So whether they know or not know what they are doing is not the issue. That is not what MPs are there to do. The foundation of the consociational system tells you MPs have no role, because it is a system based on elite cooperation.”42

Another problem is patronage politics, which has become the ruling ideology of the sectarian system. “People do not want ideas, they want people that can put these ideas to work,” explains Shamseddine, referring to the public’s exasperation with speechmaking uncoupled from concrete and particular changes. One of LiBaladi’s candidates, Gilbert Doumit, roams the pub streets of Badaro and the neighborhoods of Achrafieh as part of his campaign strategy. After having a drink with the candidate, a voter told me, “I like that they are humble, but I don’t think they have what it takes to be dirty in politics.” Nadim Gemayel, an establishment candidate of the Kataeb party, also decided to roam the streets of Beirut’s first district and sip some drinks with the youth of today. The only difference: Gemayel was able to offer one of the pubs a free pass for a night from the closing-time restrictions imposed by the internal security forces in the area.

Shamseddine criticizes these tactics, saying that the anti-status-quo groups “need to mobilize, and not meet at a hotel.” Many are trying to do exactly that, but with each and every constituency already under such tight control by political bosses, forays into someone else’s territory in order to win new supporters becomes risky business. Socioeconomic class plays into it as well: Geagea confesses, “I can’t bring myself to go to the poorest of the poor and philosophize about democracy, I just can’t, when they can barely feed their families. What am I going to tell them if I have nothing to offer?” Avoiding these possible constituents, however, has earned challengers like Geagea accusations of elitism. “What I would like to tell [the poor],” Geagea tells the audience at the debate in March, “is take a chance on us, give us the benefit of the doubt, test me in four years, and then evaluate me.”43 It’s hard to know what to make of such a plea, though, when it comes as part of her speech formally resigning her candidacy.

The “Republic of Distractions:” Identity Mobilization Strategies among the Ruling Parties

The establishment parties have opted for a double campaign strategy that both centralizes the state project and rekindles sectarian fears. Even when they struggle to form alliances, they seem confident that the same old strategies might still pay off.

The slogans they adopt—slogans of change, reform, hope, and resistance— are two-faced. Many of them, such as, “It is time,” “We are the strong party,” “We are the blue bead of luck,” “Your vote is hope for state development, and for sovereignty, ” or “My vote is for fidelity, for tomorrow, and for protection” or “The pulse of change,” not only fight over who is the real defender of the state project, but also over what defending the state project actually means.44 Propagandists in principle, the very ruling elite that have institutionalized sectarianism and corruption now want Lebanon to believe that they are the agents of anti-corruption, development, and prosperity. Basically, all these slogans say is: “Try us again.”

Although many have ridiculed these campaign slogans over social media, the political class no longer fears challenges from civil society groups, whose soft rhetoric and electoral programs they have been able to co-opt into their own political platforms. The campaign of the Lebanese Forces (LF) is a case in point: their campaign slogan speaks about the need to fight corruption, to instantiate accountability, to uphold the constitution, and build state institutions; and, of course, to disarm Hezbollah.45 They even wrote up a detailed electoral program that can be accessed on their website.

Co-opting civil-society rhetoric has become a necessary inconvenience. If there is anything the Zuama know how to do best, it is how to rile people up on matters completely unrelated to policy. Blogger Ramez Dagher calls Lebanon “the republic of procrastination,”46 “the republic of resignations,”47 and “the republic of distractions,”48 depending on the season. Now is the season of distractions and role-play: this is just another episode of political entertainment. And so, they have all banded together only to revive their differences—a semblance of the March 14 and March 8 alliances. Even when the 2009 alliances no longer hold, their spirit and force lingers on; all else, including challenger groups, becomes redundant.

The Future Movement (FM) has been facing many challenges from within and without. Their relationship with their long-time ally, the Lebanese Forces, has faltered. The LF and FM barely formed one allied list across all of Lebanon—in the predominantly Shiite district of Baalbeck-Hermel—whereas the FM allied with the FPM, an ally of Hezbollah, in more than one district. The LF campaign launch rally crowned the party as the only remaining guardian of the March 14, 2005 demonstrations that ended the twenty-nine-year long Syrian occupation over Lebanon.

Similarly, the FM has been struggling to keep its stature as the sole representative of the Sunni sect in Lebanon, with multiple contenders such as previous prime minister Najib Mikati, and previous justice minister Ashraf Rifi contesting the rule of the Future Movement in Tripoli. During his tour to introduce his party’s electoral lists, in Sunni-majority areas colloquially known as the “Sunni Nerve” areas, Hariri, of course, decided to appeal to emotion and raise the bar of entertainment. In the northern city of Tripoli, where he will face one of his toughest challenges yet, he questioned Mikati’s loyalty and ridiculed Rifi’s macho and conspiratorial logic.49 In Beirut, Hariri rallied, “There are only two currents, no third current: Hezbollah and us.”50 And to the second district of Beirut, Hariri prompted, “Let May 7, 2018 be a reminder of May 7, 2008,” pointing to the 2008 conflict when March 14 and March 8 clashed and Lebanon was on the brink of an all-out sectarian war. In all his rallying, Hariri has one clear message: whoever does not vote for us, is voting for Hezbollah; and whoever runs against us, is with the resistance axis.

Similarly, Hezbollah formed, as usual, a nation-wide alliance with the Shia Amal Movement under the “Hope and Loyalty” campaign title. The “Shia Duo” always seek to avoid intra-sectarian competition and divide up their labor: the Amal movement, under party leader and speaker of parliament (since 1992) Nabih Berri, takes the lead to defend the state and coexistence, whereas Hezbollah engages the FM in a war of words. However, in this year’s elections, Hezbollah has expanded its famous tagline, “people, resistance, army,” adding a bit more “state” into the formula. After Hezbollah dislodged a Jihadi stronghold on the Syrian–Lebanese border towns of Arsal and Baalbeck last year,51 and secured its stature as a regional actor after its involvement in the Syrian war, the party began to staunchly emphasize its commitment to the state, the integrity of its borders, and its institutions. Introducing his party’s electoral program in a televised speech, Secretary General Hassan Nasrallah said the party was once part of talks on a national defense strategy when speaker Nabih Berri led them.52 Also, for the first time, Nasrallah touched on economic and financial policies, including the Paris and Rome donor conferences, and the “frightening” situation of the public debt—usually a topic reserved for the Future Movement and other parties. Just recently, in a televised speech as part of an electoral rally in the south of Lebanon, Nasrallah criticized the FM for failing to boost the economy. Whereas “[Hezbollah] has been able to say, ‘these are my successes.’ We protect our country. …where is the success of the economy file?”53

Hezbollah has also had its share of political theater. In the Baalbeck-Hermel district, which holds six Shia seats and is a bastion for Hezbollah, media buzz in mid-March quoted Nasrallah in a private address to the residents, “We will not allow those allied with Nusra Front and Daesh to represent the people of Baalbeck-Hermel,”54 pointing to Saudi Arabia’s sponsorship of the Future Movement. Later, in a televised speech on March 24, 2018,55 Nasrallah explained that only some of the candidates on competing lists supported, armed, and visited armed groups and “prevented the Lebanese army from ending battle with them,” but that those who “supported our position a 100%” are our allies. The people of Baalbeck-Hermel will either decide to support those that “defended them for years and lived in the barrens during the snow,” or those who didn’t. Both the FM and Hezbollah have given their voters a fait accompli: you are either with us or with them.

The Future of Political Mobilization: Challenger Groups at a Crossroads

In Lebanon, individuals and groups working to challenge the establishment elite and uproot the sectarian political system are at a crossroads. Indeed, this year’s electoral battles have underlined many of their political differences, strategic disagreements, reluctances, and personal reservations; and their chances of acquiring any leverage in the service of reform seem slim to none. But 2018 may prove to be a midpoint in a process of political maturation. One of two things is likely to come next: either challenger and civil society groups grow beyond their electoral machines into a viable political option and together establish a legitimate political party; or else existing political parties will continue to find more effective strategies of identity mobilization, and thereby more deeply entrench their patronage networks into the state and its institutions. These elections could very well be what political challengers need to forge the unity and mobilization necessary to turn the tables later on down the road. In a country known, as mentioned, for its well-worn political cynicism, let’s hold out at least a little hope.

Notes

- Full text of the Adwan Election Law in Arabic, Annahar, https://www.annahar.com/article/601400-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%86%D9%87%D8%A7%D8%B1-%D8%AA%D9%86%D8%B4%D8%B1-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%86%D8%B5-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%83%D8%A7%D9%85%D9%84-%D9%84%D9%85%D8%B4%D8%B1%D9%88%D8%B9-%D9%82%D8%A7%D9%86%D9%88%D9%86-%D8%A5%D9%86%D8%AA%D8%AE%D8%A7%D8%A8-%D8%A3%D8%B9%D8%B6%D8%A7%D8%A1-%D9%85%D8%AC%D9%84%D8%B3-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%86%D9%88%D8%A7%D8%A8.

- Joseph Haboush, “New electoral law: A detailed breakdown,” Daily Star, June 15, 2017, http://www.dailystar.com.lb/News/Lebanon-News/2017/Jun-15/409720-new-electoral-law-a-detailed-breakdown.ashx.

- Ramez Dagher, “The Adwan Electoral Law: From Bad to Worse?” Moulahazat, June 18, 2017, https://moulahazat.com/2017/06/18/the-adwan-electoral-law-from-bad-to-worse/ ; For more analysis of the electoral law, see “The New Electoral Law: How Does it Work,” Blog Baladi (blog), June 19, 2017, http://blogbaladi.com/the-new-electoral-law-how-does-it-work/, and Anthony El Ghossain. “One Step Forward for Lebanon’s Elections,” Carnegie Middle East Center, July 11, 2017, http://carnegie-mec.org/sada/71496.

- Thanassis Cambanis, “People Power and Its Limits: Lessons from Lebanon’s Anti-Sectarian Reform Movement,” The Century Foundation, March 29, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/report/people-power-limits/; also see, Ziad Abu-Rish, “Garbage Politics,” Middle East Research and Information Project Middle East Report 277, 2017, http://www.merip.org/mer/mer277/garbage-politics.

- Walid Hussein, “Lebanon’s Upcoming Parliamentary Elections Candidates: Hope or Illusion?”, Raseef22, March 17, 2018, https://raseef22.com/en/politics/2018/03/17/lebanons-upcoming-parliamentary-elections-candidates-hope-illusion/.

- “Lebanese electoral law 2017: Full text in English,” Daily Star, April 24, 2018, http://www.dailystar.com.lb/News/Lebanon-News/2017/Jul-07/411988-lebanese-electoral-law-2017-full-text-in-english.ashx.

- Robert F. Worth, “Foreign Money Seeks to Buy Lebanese Votes,” New York Times, April 22, 2009, https://www.nytimes.com/2009/04/23/world/middleeast/23lebanon.html.

- Elias Muhanna, “Is Lebanon’s New Electoral System a Path out of Sectarianism?” New Yorker, June 29, 2017, https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/is-lebanons-new-electoral-system-a-path-out-of-sectarianism.

- Edmond Sassine, “Report: In these elections: March 14 and March 8 political alignments completely changed,” LBCI, March 17, 2018, https://www.lbcgroup.tv/news/d/news-bulletin-reports/368248/report-in-these-elections-march-14-and-march-8-pol/en.

- Sami Atallah and Zeina El Helou, “Lebanese Elections: Underhanded Strategies to Gain an Edge,” Lebanese Center for Policy Studies, April 2018,

[Arabic] https://www.lcps-lebanon.org/featuredArticle.php?id=136 and [English] https://www.lcps-lebanon.org/featuredArticle.php?id=141. - Sami Atallah and Zeina El-Helou, “Lebanese Elections: Underhanded Strategies to Gain an Edge,” Lebanese Center for Policy Studies, April, 2018, https://www.lcps-lebanon.org/featuredArticle.php?id=141.

- Ramez Dagher, “The Adwan Electoral Law: From Bad to Worse?,” Moulahazat, July 18, 2017,

https://moulahazat.com/2017/06/18/the-adwan-electoral-law-from-bad-to-worse/. - Ramez Dagher, “The Adwan Electoral Law: From Bad to Worse?” Moulahazat, June 18, 2017, https://moulahazat.com/2017/06/18/the-adwan-electoral-law-from-bad-to-worse/.

- “The Garbage Crisis in Lebanon: From Protest to Movement to Municipal Elections,” Tadamun, May 19, 2016, http://www.tadamun.co/2016/05/19/garbage-crisis-lebanon-protest-movement-municipal-elections/?lang=en#.Wrg7Gr1uaCQ.

- Matt Nash, “The anti-establishment: A new opposition,” Executive, September 13, 2017, http://www.executive-magazine.com/cover-story/the-anti-establishment.

- Timour Azhari, “Out with the old? The new faces seeking votes,” Daily Star, February 20, 2018, http://www.dailystar.com.lb/News/Lebanon-News/2018/Feb-20/438624-out-with-the-old-the-new-faces-seeking-votes.ashx.

- Timour Azhari, “Lebanon’s independent groups announce 9 lists,” Daily Star, April 9, 2018, http://www.dailystar.com.lb/News/Lebanon-News/2018/Apr-09/444615-independent-groups-announce-9-lists-across-lebanon.ashx.

- Mohammad Shamseddine (Policy and Research Specialist at Information International), interview with the author, March 9, 2018.

- Open public debate at Mezyan café in Hamra, Beirut with Assad Thebian, March 27, 2017.

- Sabaa Web TV, “The Electoral Program of Sabaa,” Youtube, March 21, 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VIjnckMBhDM.

- “When the ‘civil societies’ compete in the capital,” Al Mulhak, March 5, 2018, [Arabic] http://www.mulhak.com/%D8%B9%D9%86%D8%AF%D9%85%D8%A7-%D8%AA%D8%AA%D9%86%D8%A7%D9%81%D8%B3-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85%D8%AC%D8%AA%D9%85%D8%B9%D8%A7%D8%AA-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85%D8%AF%D9%86%D9%8A%D8%A9-%D9%81%D9%8A-%D8%A7/.

- Open public debate between Nayla Geagea and Assad Thebian at Mezyan café in Hamra, Beirut, March 27, 2017.

- Facebook post, LiBaladi official Facebook page, March 25, 2018, accessed Apirl 24, 2018, https://www.facebook.com/LiBaladiOfficial/posts/912668908894102?pnref=story.

- Open public debate between Nayla Geagea and Assad Thebian at Mezyan café in Hamra, Beirut, March 27, 2017.

- Electoral districts and list distribution, Annahar, https://www.annahar.com/elections/districts.

- Open public debate between Nayla Geagea and Assad Thebian at Mezyan café in Hamra, Beirut, March 27, 2017.

- Michael Young, “Is Lebanon Heading Towards Economic Bankruptcy?” Carnegie Middle East Center, October 5, 2017, http://carnegie-mec.org/diwan/73280.

- Wissan Lahham, “Lebanese Ruling: The Constitution is sovereign, not Parliament,” The Legal Agenda, December 4, 2017, http://legal-agenda.com/en/article.php?id=4083.

- Nizar Saghieh, “Lebanon Unlimited: Neoliberalism Dominates the Workplace,” The Legal Agenda, June 4, 2015, http://legal-agenda.com/en/article.php?id=709&folder=articles&lang=en.

- “Housing as a Right: Contesting the Constitutionality of Lebanon’s Rent Law,” The Legal Agenda, July 7, 2014, http://legal-agenda.com/en/article.php?id=627&folder=articles&lang=en.

- Charbel Nahhas, “Parliamentary Elections and Change,” lecture, Jil Organization and Citizen in a State, Beirut, February 17, 2018.

- Ahmad Al Assi (member of Citizens in a State), interview with the author, February 28, 2018.

- Ahmad Al Assi (member of Citizens in a State), interview with the author, February 28, 2018.

- Walid Hussein. “Lebanese Elections and the Disarmament of Hezbollah: The Ultimate Test,” Raseef22, February 2, 2018, [Arabic] https://raseef22.com/politics/2018/02/06/%D8%B3%D9%84%D8%A7%D8%AD-%D8%AD%D8%B2%D8%A8-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%84%D9%87-%D8%B9%D9%84%D9%89-%D8%B7%D8%A7%D9%88%D9%84%D8%A9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AA%D8%AD%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%81%D8%A7%D8%AA-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A7%D9%86/.

- Kelna Beirut official Facebook page, accessed April 24, 2018, https://www.facebook.com/KelnaBeirut/.

- Kelna Beirut Facebook page, keynote speech of Kelna Beirut candidate Ibrahim Mneimneh, https://www.facebook.com/KelnaBeirut/videos/1898759790136570/.

- Victoria Yan and Finbar Anderson, “Voters split on independents’ ability to offer real change,” Daily Star, April 11, 2018, http://www.dailystar.com.lb/News/Lebanon-News/2018/Apr-11/444751-voters-split-on-independents-ability-to-offer-real-change.ashx.

- “Candidacies to the parliamentary elections: women and the sons of politicians are the stars of the season,” Raseef22, March 7, 2018, [Arabic] https://raseef22.com/politics/2018/03/07/%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AA%D8%B1%D8%B4%D9%8A%D8%AD%D8%A7%D8%AA-%D9%84%D9%84%D8%A7%D9%86%D8%AA%D8%AE%D8%A7%D8%A8%D8%A7%D8%AA-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%86%D9%8A%D8%A7%D8%A8%D9%8A%D8%A9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%84%D8%A8%D9%86/.

- Hussein Dakroub, “Election ticket deadline ends with 77 lists submitted,” Daily Star, march 27, 2018, http://www.dailystar.com.lb/News/Lebanon-News/2018/Mar-27/443161-election-ticket-deadline-ends-with-77-lists-submitted.ashx.

- Mohammad Shamseddine (Policy and Research Specialist at Information International), interview with the author, March 9, 2018.

- For more on the performance of parliamentarians over the past nine years, see the Lebanese Center for Policy Studies (LCPS) assessments, http://niyabatanani.com/.

- Khalil Gebara, “Building Pluralistic and Inclusive States Post-Arab Spring,” conference, The Baker Institute and Issam Fares Institute for Public Policy and International Affairs, February 1, 2018, https://www.facebook.com/events/200989407150268/.

- Open public debate at Mezyan café in Hamra, Beirut with Assad Thebian, March 27, 2017.

- Nada Ayoub. “Election Slogans for 2018, ‘Try Us One More Time’,” Annahar, March 23, 2018, [Arabic] https://www.annahar.com/article/780678-%D8%B4%D8%B9%D8%A7%D8%B1%D8%A7%D8%AA-%D8%A7%D9%86%D8%AA%D8%AE%D8%A7%D8%A8%D8%A7%D8%AA-2018-%D8%B3%D9%84%D9%8A%D9%85%D8%A9-%D9%81%D9%8A-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B4%D9%83%D9%84-%D9%88%D8%B4%D8%AF-%D8%B9%D8%B5%D8%A8-%D9%81%D8%A7%D8%B1%D8%BA-%D9%81%D9%8A-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85%D8%B6%D9%85%D9%88%D9%86.

- See the Lebanese Forces (LF) party election website with full electoral program, https://elections.lebanese-forces.com/; also see Kataeb party election website with a full electoral program, http://nabad2018.com/; and Free Patriotic Movement (FPM) elections website, https://elections.tayyar.org/home.

- Ramez Dagher, “The Republic of Procrastination,” Moulahazat, May 15, 2017, https://moulahazat.com/2017/05/15/the-republic-of-procrastination/.

- Ramez Dagher, “The Republic of Resignations,” Moulahazat, November 4, 2017, https://moulahazat.com/2017/11/04/the-republic-of-resignations/.

- Ramez Dagher, “The Republic of Distractions,” Moulahazat, August 29, 2017, https://moulahazat.com/2017/08/29/the-republic-of-distractions/.

- “REPORT: Hariri targets Mikati and Rifi in his electoral speech from Tripoli,” LBCI, March 25, 2018, https://www.lbcgroup.tv/news/d/news-bulletin-reports/369689/report-hariri-targets-mikati-and-rifi-in-his-elect/en.

- “Hariri: May 7 2018 is a response to May 7 2008,” Al Mustaqbal, March 24, 2018, http://almustaqbal.com/article/2030722/%D8%B9%D8%AF%D8%AF-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%8A%D9%88%D9%85/%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AD%D8%B1%D9%8A%D8%B1%D9%8A-7-%D8%A3%D9%8A%D8%A7%D8%B1-2018-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B1%D8%AF-%D8%B9%D9%84%D9%89-7-%D8%A3%D9%8A%D8%A7%D8%B1-2008.

- Thanassis Cambanis, “Strengthened by War, Hezbollah Displays Regional Power,” The Century Foundation, July 28, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/strengthened-war-hezbollah-displays-regional-power/.

- “Sayyed Nasrallah’s Full Speech Announcing Hezbollah’s Electoral Program,” Alahed News, March 24, 2018, https://english.alahednews.com.lb/essaydetails.php?eid=42562&cid=576#.WsK7vNVuZO0.

- “Nasrallah blasts Future’s ‘failure’ to boost lebanon’s economy,” Daily Star, April 21, 2018, http://www.dailystar.com.lb/News/Lebanon-News/2018/Apr-21/446211-nasrallah-blasts-futures-failure-to-boost-lebanons-economy.ashx.

- “Opposition to Hezbollah–Amal list in Baalbeck-Hermel ‘allies of Daesh and Nusra’: Nasrallah,” Daily Star, March 16, 2018, http://www.dailystar.com.lb/News/Lebanon-News/2018/Mar-16/441806-opposition-to-hezbollah-amal-list-in-baalbeck-hermel-allies-of-daesh-and-nusra-nasrallah.ashx.

- “Sayyed Nasrallah’s Full Speech Announcing Hezbollah’s Electoral Program,” Alahed News, March 24, 2018, https://english.alahednews.com.lb/essaydetails.php?eid=42562&cid=576#.WsK7vNVuZO0.