Introduction

The official child poverty rate in the United States stands at 20 percent, the second-highest among its developed counterparts, for a total of almost 15 million children. Since the 2008 recession, 1.7 million more kids have fallen into poverty, according to UNICEF’s relative measure of poverty.

Compared to other age groups, a much higher share of Americans aged 0 to 18 are impoverished.

Let that sink in for a minute.

Why are we allowing so many Americans to start their lives in poverty, knowing that it likely will do them significant long-term damage, as well as limit our growth as a nation? It is a blow to our nation’s dedication to equal opportunity.

That question is especially perplexing because relatively simple, proven approaches would address some of the worst impacts of child poverty. What follows are seven lessons drawn from The Century Foundation’s Bernard L. Schwartz Rediscovering Government Initiative conference last June, Inequality Begins at Birth, that would help us tackle gaps in our public policy, as part of the Initiative’s equal opportunity agenda. The lessons are as follows:

- The Stress of Childhood Poverty Is Costly for the Brain and Bank Accounts

- Child Poverty Is Not Distributed Equally

- The Power of Parental Education

- Higher Minimum Wage Is a Minimum Requirement

- Workplaces Need to Recognize Parenthood

- Government Works

- Cash Allowances Are Effective

Lesson 1: The Stress of Childhood Poverty Is Costly for the Brain and Bank Accounts

Recent evidence suggests that we should ditch the common dichotomy of nature-versus-nurture.

As it turns out, the two factors are not so distinct — your environment can actually alter the expression of your genes, creating interactions between the two, rather than separating them.

This finding has important implications for child poverty policy.

If environmental shortcomings can actually affect the expression of a child’s genes, then childhood poverty may well affect a child’s neurological development, creating deficiencies that persist throughout the child’s lifetime. Although we have known about correlations between child poverty and negative outcomes, such as poor health, we now understand the biological reasons behind this phenomenon.

The main conclusion? Growing up in poverty can directly damage development of a child’s brain.

“We’ve known about the direct influence of poverty on child health…what are we starting to understand now is that this doesn’t end.” — Dr. David Keller

These kinds of findings are the cornerstone of epigenetics, the field of study that examines how genes are turned on or off during our lifetime due to environmental factors. As a fairly new area of science (the American Academy of Pediatrics [AAP] created an agenda including epigenetics only as recently as 2011), it contains many important discoveries that should get us to rethink child poverty policy.

For example, a study done by Marcus Pembrey examined forty men, half of whom were born into rich households, and the other half into poor ones, looking for differences. At 45 years of age, the men’s epigenetic patterns varied according to the wealth and income levels of their childhood homes, not their adult ones.

This study, while small, nevertheless suggests that income-correlated epigenetic changes that occur during childhood development stick around for life.

What Does This Mean for Children in Poverty?

Growing up in poverty exacerbates negative environmental factors for children. Scientists label the immediate, physiological result “toxic stress.”

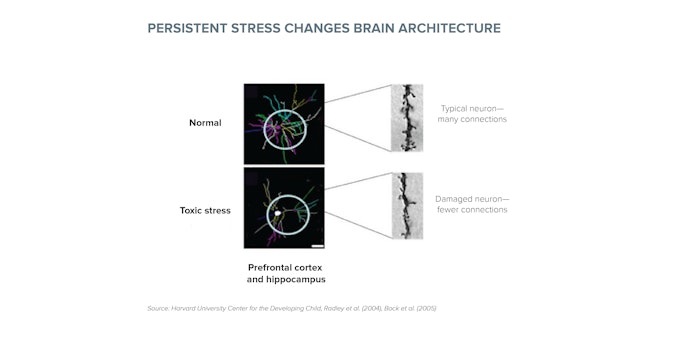

Humans have specific hormones that are released when our bodies sense danger. These “stress” hormones are released in emergency situations, such as if we were to be attacked by a predator. Scientists have recently discovered that, with repeated exposure to stressful situations, our bodies release high levels of these toxic stress hormones — overtaxing our bodies in ways that actually rewire our brains.

For children living in poverty, toxic stress is a common occurrence.

It should come as no surprise then, that these children face neurological repercussions from their abnormally high exposure to stress.

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) — which range from physical abuse, to having an incarcerated parent, to, maybe the most eye-opening, facing emotional neglect — increase the amount of toxic stress children face. Those living in poverty are significantly more likely to have more of these experiences than those living above the poverty line.

But childhood need not be so obviously traumatic to create adverse effects. Studies have found that even repeated but relatively low-levels of stress inducers — such as hearing gunshots at a distance, or the lack of quality time with parents — can induce toxic stress. On the most basic level, time spent with children is a luxury low-income parents often cannot afford.

The end result of childhood toxic stress is lasting. Over-production of stress hormones can switch off genes necessary for healthy neuronal connections and strong development later in life.

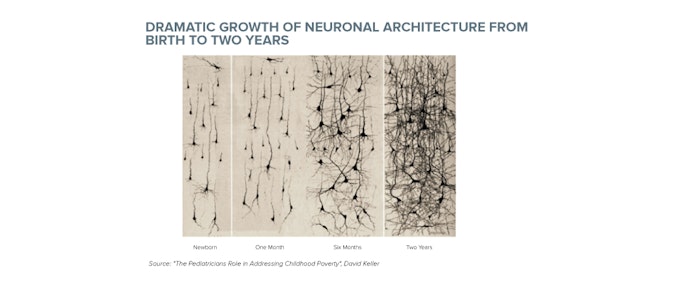

About 90 percent of a child’s brain development occurs before the age of five. In the first few years, as many as 700 neurons form a connection per second. When toxic stress interferes with these connections, it affects a child’s neurological development, leading to lifelong problems.

Effects of Toxic Stress

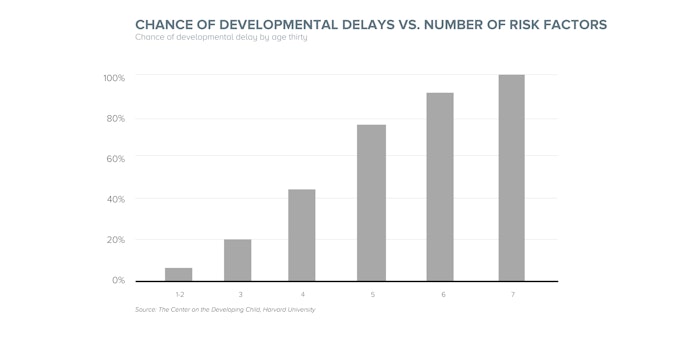

The Center on the Developing Child at Harvard has shown that there is a 90-100 percent chance of developmental delays when children under age 3 experience six to seven risk factors (such as poverty, single-parent households, or low maternal education) as defined by a report by University of Maryland’s Dr. Richard Barth. Developmental delays are when a child does not reach certain milestones in the normal age range (such as starting to talk before age 2).

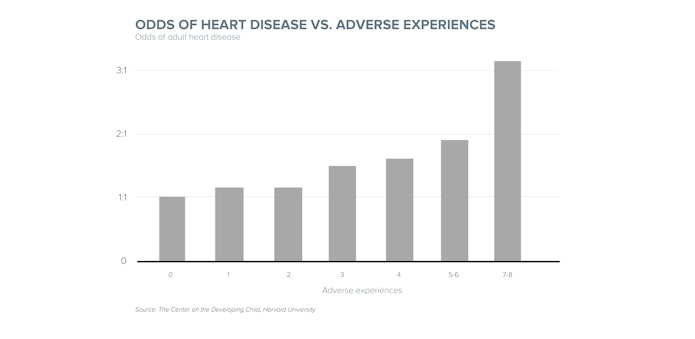

Children who experience seven to eight ACEs, such as abuse, physical neglect, or household dysfunction, are three times more likely to have cardiovascular disease as an adult.

Neurons that have been exposed to toxic stress are underdeveloped, with weaker and fewer connections.

A Hard Problem with a Simple Remedy

Money may not buy happiness, but as it turns out, it sure can help with neuronal connections.

Anti-poverty policy aimed at improving early childhood, such as the Strong Start For America’s Children Act, can help protect children’s brains and level the playing field later. Being poor changes a child’s development neurologically, setting the stage for disadvantage later in life. A tree that is knocked down by a storm as a sapling has a much harder time growing up healthy later on, and the same goes for our children.

Lesson 2: Child Poverty Is Not Distributed Equally

“I would just like to go explore the world, but I’m never going to be able to do it because, these days, everything is expensive,” states Kaylie, a 10-year-old girl living with her family in a motel. She is featured in the PBS documentary Poor Kids, which examines poverty through the perspective of the children themselves. Still in elementary school, Kaylie assumes a matter-of-fact tone when pricing out her dreams. However, her case is not unique.

While children are the poorest age group in America, the youngest children are the poorest of all.

Twenty percent of children under age 18 are poor, compared to 23 percent of children under age 5 — that’s enough toddlers living under the poverty line to populate the state of Alabama, with some left over.

“We are dramatically undercapitalized in the stage of life that is most influential.” — Lawrence Aber

The numbers are even worse for African American and Hispanic children. Forty-two percent of African American children under age 5 are poor, meaning that the odds of an African American child being born poor are just about the same as the same child’s odds of graduating college. Thirty-six percent of Hispanic children under age 5 are poor.

If we dig deeper, we see that not only are a large number of children under age 5 poor, half of them are extremely poor — that is, living in households whose annual income is under half of the poverty line, currently $11,641 for a family of four (an already outdated measure).

The Heckman Equation

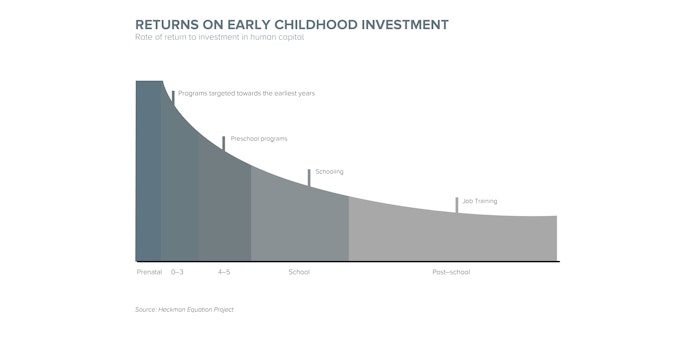

Although public investment in K-12 education is substantial in the United States, relatively little is spent on children aged 0 to 5, the most undercapitalized group in the nation.

Numerous studies have shown that programs that give kids an early start actually work, and have a high rate of return.

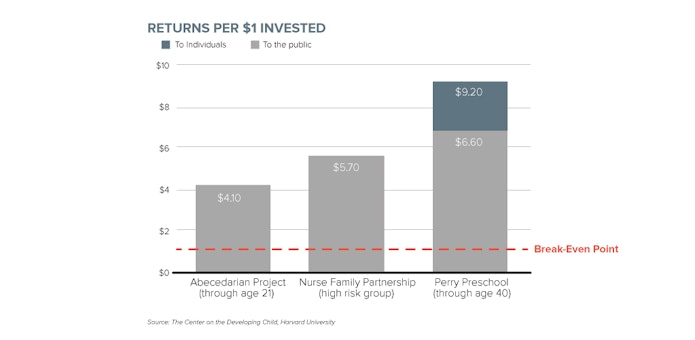

In the late 1960s, the Perry Preschool Study enrolled children born into poverty and at high risk of failure into a high-quality preschool.

The researchers found that the children in the study had higher earnings, were better educated, and less likely to be incarcerated than the control group — and that those improvements were still visible over forty years later.

The Nobel-laureate economist James Heckman calculated a 7 to 10 percent of return on investment from the Perry Preschool project. Heckman’s research culminated in what is now known as the Heckman Equation, a body of research that persuasively demonstrates that investment in early childhood is the best way to create a better economic life for all Americans.

Misaligned Priorities

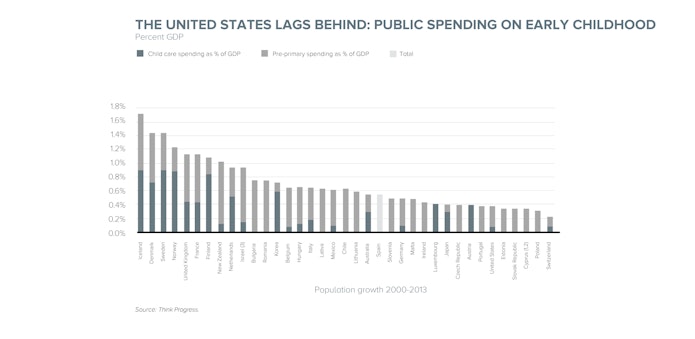

Faced with the mountain of evidence that Heckman and dozens of other researchers have amassed, the most sensible social policy would be to invest heavily in early childhood programs. Sadly, that’s exactly the reverse of current policy.

Based on OECD data, the average government expenditure per student for K-12 education is $12,550, but only $10,010 for pre-primary education. This number is far worse when taking into account our startlingly low rate of pre-primary enrollment — only 38 percent of three-year-olds are receiving childhood education. Calculating government expenditure per child, rather than per student, the amount sinks to a little over $2,000 for pre-primary education.

In comparison to other developed democratic countries, the United States ranks thirty-second when it comes to investment in early childhood.

Research shows that we can, and we should, do better when it comes to our youngest. Children like Kaylie should not have to resign from their dreams before their lives have even started.

Lesson 3: The Power of Parental Education

“I’ve never met a parent who didn’t want to give their child a head start, they just don’t know how,” stated Yolanda Minor, a home visiting specialist from Early Steps to School Success (ESSS), at the Inequality Begins at Birth conference.

One family that Minor worked with consisted of a single mother and her child living with her grandparents. When Minor came into the household, the 1-year-old, Michael, was not speaking at all. She brought books into their household and encouraged the mother to read to her son, but the grandparents ridiculed their efforts, stating, “he doesn’t understand what you’re saying…you are all wasting your time.”

After a few more visits, as they saw Michael speaking and improving, the grandparents also started reading to him. When he reached age 5, Michael’s vocabulary tested the age-equivalent of an 8-year-old.

If brain development (and inequality, for that matter) begins at birth, then so, too, should education — for both children and their parents.

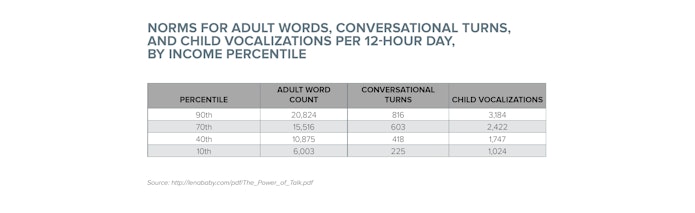

As we have seen, kids cannot become healthy adults without a supportive home environment. By the time a child is just 18 months old, disparities arise between the vocabularies of poor and wealthy children. Unfortunately, low-income households are often correlated with poor parental education and a lack of resources to change this.

The solution can be as simple as parents knowing to read to their kids.

Encouraging reading is just one of many solutions, but it is representative of how simple and powerful parental education can be. Evidence from the Lena Foundation shows that the number of words that infants hear is correlated to income inequality. Children in lower-income families tend to hear fewer words as infants, and those who hear fewer words tend to do worse developmentally, which ties into a lack of success later in life. The good news is that, regardless of economic class, all children benefit from being read to.

“The earliest safety net a child can have is a supportive family.” — Yolanda Minor

Educating Early Through Home Visiting

Home-visiting programs like ESSS bring parenting and health care education directly to low-income households. That can be a huge benefit for children whose parents might not have the time or transportation to get around.

And home-visiting programs are remarkably effective. The Home Visiting Evidence of Effectiveness (HomVEE) study identified fourteen different models that produce positive results.

The unfortunate fact is that only 4 percent of eligible infants receive Early Head Start, a federal program that includes one of our largest home-visiting options. Although such programs have delivered results, even if pediatricians inform parents of programs they are eligible for, benefits are limited if the programs are inadequately funded.

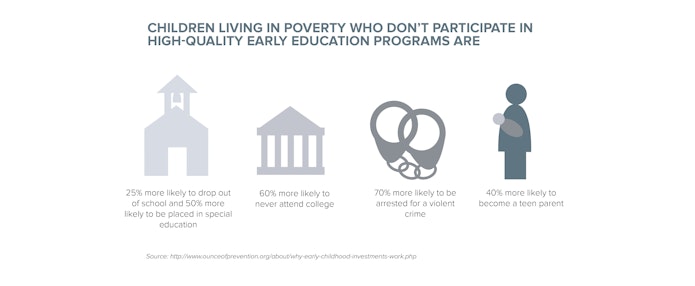

By some estimates, the rate of return for early childhood programs is approximately $4-$10 for every $1 invested. With such a high payback to both the individual and society, funding of such programs should be put at the forefront of economic policy.

The reason behind this incredible rate of return? Cheap child policy expenditures on the front end reduce the much more expensive back-end costs, such as for incarceration and health care.

In 2013, the Strong Start for America’s Children Act was introduced, which would fund and expand pre-kindergarten programs, including continued support for home-visiting and Early Head Start. Its passage would allow a desperately needed investment in our youngest, and poorest, citizens.

As Minor states, “when parents enroll in a home-visiting program, it shows that they want more for their child.” She works in rural towns in Missouri, where there may not even be a grocery store, and poverty has been passed down from generation to generation. In such towns, home-visiting programs are the only lifelines left.

Bridging the Gap With Pediatrics

Another way which we can reach parents is through pediatrics. The American Academy of Pediatrics(AAP), an organization of over 60,000 pediatricians, recently announced a new initiative. In addition to administering what we think of as classic primary care duties, such as vaccines, pediatricians will now also advise parents to read aloud to their infants. This seemingly simple solution will bridge the gap between research and those who need that information.

The initiative makes enormous sense, since the widest reach we have for kids under the age of 5 is through pediatricians.

Pediatricians educating parents about the salutary effects reading is our first course of action. They also could — and should — inform parents about the benefits they are eligible for, such as the Earned Income Tax Credit(EITC) and Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program(SNAP), as well as home-visiting and early education programs that their community offers.

Lesson 4: Higher Minimum Wage Is a Minimum Requirement

“Childhood poverty” may conjure up images of unemployed parents. But the reality is much different.

America has a virtual army of full-time working parents, many of whom remain below the poverty line. Many of those parents hold minimum-wage jobs. (The idea that most minimum-wage workers are teenagers is a myth. The truth is that the average minimum-wage worker is 35 years old, female, and works full-time. Furthermore, 28 percent of minimum-wage workers are parents.)

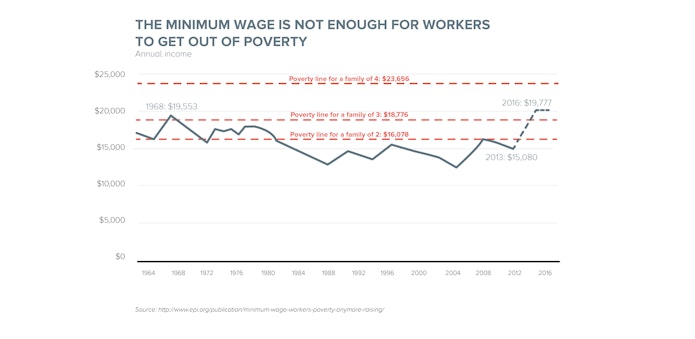

A minimum-wage employee working full-time earns an annual income of $15,080. But the federal poverty threshold for a three-person family (one adult and two children) is $18,776.

But even looking at the poverty line understates the real depth of the problem. America’s official poverty line is low. To take one estimate, a more realistic number for an actual average basic budget for a family of three is somewhere around $40,273, according to the Economic Policy Institute’s (EPI) Family Budget Calculator.

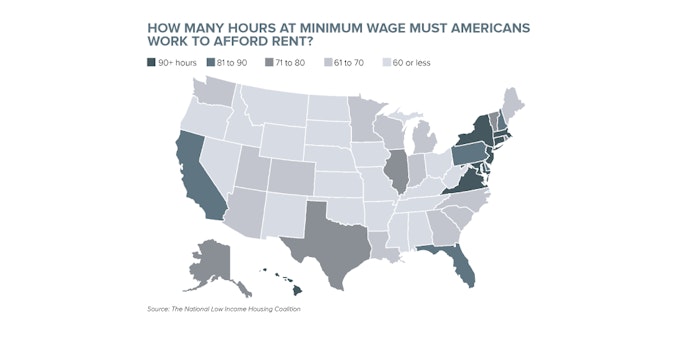

That revised income is almost three times the amount a full-time worker makes from minimum wage. So, even a two-parent family with just one child would struggle if both parents worked full time at the minimum wage. Just look at this infographic from former TCF colleague, Benjamin Landy, which shows that fifty hours is the minimum that someone making federal minimum wage must work in order to afford a one-bedroom apartment in America.

Lifting children out of poverty goes hand-in-hand with fairly rewarding their hard-working parents.

Raising the federal minimum wage to $10.10, the amount proposed by the Fair Minimum Wage Act, would benefit 7 million parents — reaching almost one in five children.

“Minimum wage is not primarily an anti-poverty tool — it’s a basic labor standard.” — Elise Gould

Where Should Minimum Wage Be Today?

The current, federal minimum wage of $7.25 does not hold up under any measurements. In real dollars (that is, if one simply adjusted the wage to keep pace with inflation), today’s minimum wage would need to be $9.40 simply to produce the same buying power that it had in 1968.

Tying the minimum wage to increases in the median American’s wage would put the figure at about $10.65 today.

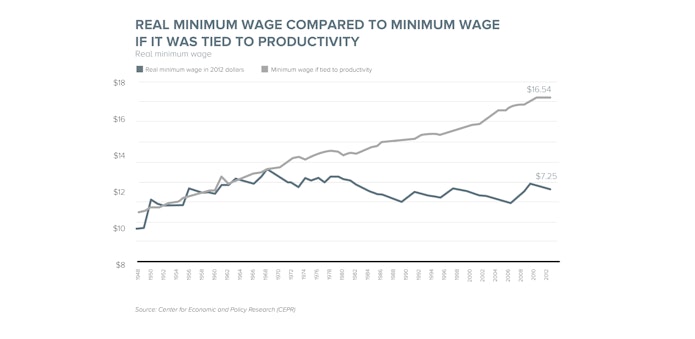

But even that number is inadequate. The productivity of low-wage workers has been increasing steadily, but wages have not kept up.

As the graph below shows, minimum wage workers would be earning $16.54 per hour had their wages kept pace with the growth rate of productivity in America.

If low-wage workers got their fair share of the pie, minimum wage would be $16.54 in 2012, representing a wage increase for 40 percent of men and 50 percent of women. That’s a conservative calculation — EPI estimates that it would be $18.30 today.

It seems we continue to wait today, for fair wages to come tomorrow.

Doesn’t Raising the Minimum Wage Cut Jobs?

Another common misconception is that raising the minimum wage would cause workers to lose their jobs.

The economic consensus shows that this is not the case. Even during rough economic times, raising the minimum wage has no adverse effect on employment. An examination of sixty-four different minimum-wage studies challenges this idea.

Who Wants to Raise the Minimum Wage?

Raising the minimum wage has often been painted as a Democratic talking point, but the truth is, over three-quarters of Americans favor increasing the federal minimum wage to $9. TCF’s Zachary Bernstein states that when Americans are asked what the minimum wage should be, the average response is $9.86.

In November 2014, four red states voted to raise minimum wage, making a total of twenty-nine states and D.C. that currently have higher minimum wages than the federal level.

In an era of increasing political polarization, where it seems Americans can’t agree on anything, a 76 percent consensus reveals the country’s desperate need for wage reform.

For a country that places a high value on rewarding hard work, there is a huge disconnect between ideals and reality if we have millions of full-time working parents struggling to make ends meet.

Lesson 5: Workplaces Need to Recognize Parenthood

Last February, Bene’t Holmes suffered a miscarriage.

But Holmes’s story isn’t so much about health care. In fact, she had perfectly good medical coverage and advice. The day before her miscarriage, her physician instructed her to work light duty — no lifting of heavy boxes.

But lifting heavy boxes was her regular job requirement as an associate at Walmart, the world’s largest private employer.

Holmes’s manager refused to comply with her physician’s orders — even though the directive was one that was regularly granted to employees with disabilities. A single mother with a child on the way, Holmes couldn’t afford to lose her job. So she lifted boxes as required.

The next day, she miscarried. And her employer refused to provide her with leave to recover.

Workplace Safety

Workplace accidents like Bene’t Holmes’s miscarriage should never happen, but currently, pregnancy is something that is all but ignored in the workplace. Although discrimination against pregnant workers is technically illegal, due to the Pregnancy Discrimination Act of 1978, courts have interpreted protections narrowly, making it difficult for workers to win discrimination claims.

A bill called the Pregnant Workers Fairness Act (PWFA)would clarify these protections for pregnant workers and protect women like Holmes from employers who would disregard their safety. Modeled after the Americans With Disabilities Act, the much needed PWFA would strike a balance between protecting workers and preventing undue hardship for employers.

“You should never have to make the decision between being a responsible parent or a dedicated employee.” — Avis Jones-DeWeever

Parental Leave

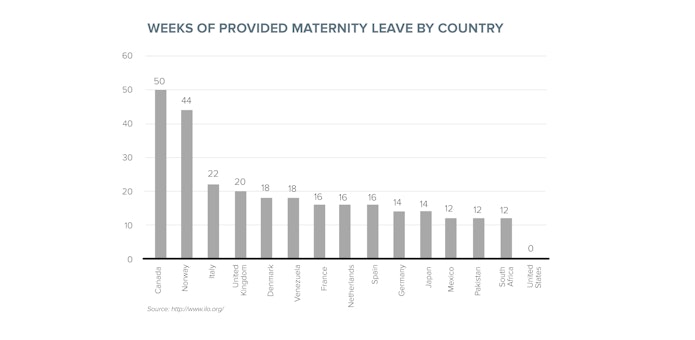

Another important step to help working parents would be to update archaic federal paid family leave policy.

Currently, when an employee in the United States has a child, they are guaranteed no paid leave at all.

Out of 178 countries, the United States is one of just three that does not offer paid maternity leave. (The other two are Papua New Guinea and Swaziland.)

U.S. employers fail to pick up the slack, with only 11 percent of private and 17 percent of public sector workers receiving paid family leave. While employers are required to provide up to 12 weeks of unpaid leave under the Family and Medical Leave Act, this is often an unfeasible option for parents living paycheck to paycheck.

A more sensible system would provide workers with a number of weeks of paid leave, allowing them to retain their jobs, thus reducing welfare expenditures and employee turnover. And in an economy that requires many families to have two working parents, it simply does not make sense — for the family or for the employer — for one parent to stop working to have children.

“Paid leave is not just about the perk, it’s about losing your wages when you have to take your child for a flu shot.” — Jodie Levin-Epstein

Support for Child Care

Parenting doesn’t end when employees return to work, and neither should government support.

In the United States, 11 million children under the age of 5 are in some type of child care, each one clocking an average of about thirty-six hours per week. We now know that this is the most crucial time of a child’s life, yet high-quality child care is far out of the reach of many parents, forcing them to economize on their children’s future.

When you realize that the average annual income for a full-time child care professional is just under $21,500, it’s not hard to see why high-quality child care is hard to come by. While that salary is about $100 more than we pay parking lot attendants, it is still less than we pay housekeepers. When child care is not valued, we get what we pay for — and it’s our kids who suffer. As we’ve seen, most of brain development happens while our children are still of typical child care age.

But despite the undervalued nature of child care, for parents, it is still a costly undertaking. Annual out-of-pocket child care costs for parents are, on average, more than yearly costs to enroll their children in public universities. This is partly because spending on the Child Care Development and Block Grant (CCDBG), the primary source for public assistance of child care, has remained stagnant since 2002, serving only one out of every six eligible children, leaving most parents to fend for themselves.

Helping our children should start with ensuring that their parents get treated fairly in the workplace. On a foundational level, we would do well to rebrand parenting as a collective good that requires support from all of us.

Lesson 6: Government Works

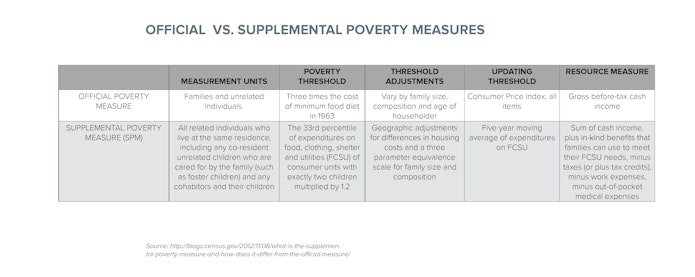

In 1987, then-president Ronald Reagan quipped that Americans “fought a war on poverty and poverty won.” Anyone looking at the official poverty measure (OPM) might be tempted to agree.

However, the official poverty measure is notoriously inaccurate.

Fortunately, better measures exist. In 2010, the Census Bureau introduced the supplemental poverty measure (SPM) to address the official measure’s shortcomings. While the official measure defines poverty as earning less than three times the cost of a minimum food diet in 1963, the SPM sets the poverty threshold at the thirty-third percentile of current expenditures on food, clothing, shelter, and utilities.

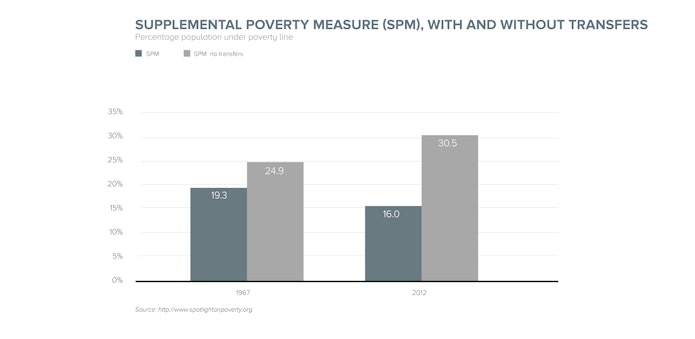

Another aspect that the official measure does not take into account are what wonks call “taxes and transfers.” That’s mostly shorthand for the plethora of tax credits (like the Earned Income Tax Credit) and transfer programs (Medicaid, Social Security, housing vouchers, and so on) that are available to the nation’s poor. The SPM, on the other hand, includes these resources in its measurement.

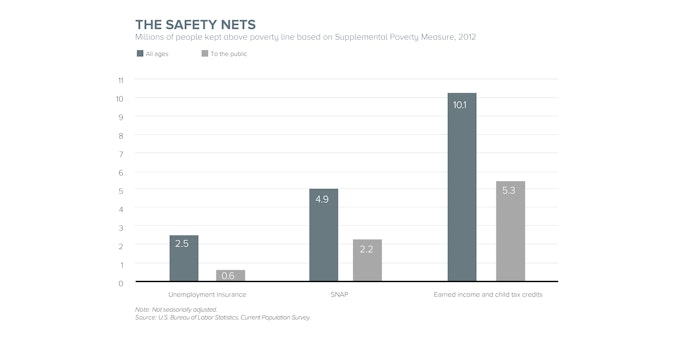

The difference is startling. As the graph below shows, the safety net cuts poverty in half.

In 2012, this meant that the federal safety net kept over 40 million people out of poverty.

Safety net programs are making a real difference. It’s worth taking a closer look at what’s working to see how we might be able to make even greater inroads.

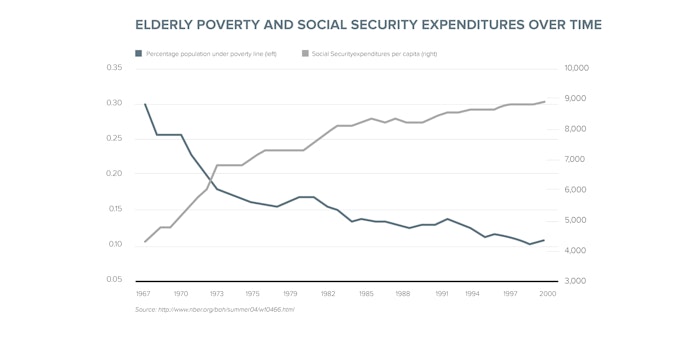

Social Security

The creation and expansion of Social Security over the course of the Twentieth Century vastly reduced poverty among the elderly. The graph below shows that trends in Social Security spending correlate highly with reduction in elderly poverty levels.

In 2012, just over 9 percent of elderly Americans were below the poverty line. However, without Social Security benefits, this number would rise to 44 percent.

Elderly poverty remains below the overall poverty rate because of FDR’s foresight and social spending. It is perhaps our best example of the effectiveness of public policy in reducing poverty.

Now, we just need to find the political will to do the same for our children.

Expanding Refundable Credits

At the moment, government’s most effective tool for addressing child poverty has been refundable tax credits, such as the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and the Child Tax Credit (CTC), which lift almost 5 million children out of poverty.

Unfortunately, as Robert Greenstein noted at the Inequality Begins at Birth conference, recent expansions of these credits are scheduled to expire in 2017.

These credits were last extended in 2013. If these improvements had been allowed to expire, it would have caused almost 16 million children to lose some or all of their EITC and CTC, sending 7.7 million childreninto, or deeper into poverty.

The average credit a family with children receives from EITC is around $3,000. To some, it might not seem like much, but it’s easy to overlook the importance of an extra $3,000 per year for a family living in poverty. Debts can be paid off, parents can make car payments so that they can drive to work, or afford child care and healthier food.

At the conference, Joanna Cruz, a member of Witness to Hunger, an organization that gives voice to mothers in poverty, embodied this sentiment when she talked about her own experiences trying to feed and clothe her children. For example, she stated that after receiving a $200 gift card, “We got to buy Cheerios this month…it didn’t dawn on me that I had cut out little stuff like cereal.”

Although there is always room for innovation, we know what works when it comes to cutting poverty levels — and it’s not less government social spending.

Lesson 7: Cash Allowances Are Effective

Joanna Cruz, a single poor working mother, told guests at the Inequality Begins At Birth conference, “An extra $350 per month…that’s extra food, boxes of cereal I can buy. I could use it to pay off my classes, or my loans.”

“My goals are not the same as the next person’s…people need to stop categorizing all of us together,” Cruz continued.

Cruz was making an impassioned case for cash allowances — that is, for poverty programs that simply give cash to poor people with children.

Cash allows different people in completely different environments to do what’s best for them. After all, a working, single-mother in rural Missouri has very different needs from an unemployed family of four living in New York City.

Cash allowances can empower individual agency by operating on the assumption that the person who is mostly likely to know what you and your children might need is, well, you.

And unlike existing anti-poverty programs, such as the Earned Income Tax Credit and Child Tax Credit, which do not to apply to parents who have no earnings, cash allowances are available to everyone. Plus, cash allowances can be paid out weekly or monthly rather than annually, a distinction that matters greatly to families living paycheck to paycheck.

Why Cash Allowances?

The biggest thing that poor people lack is money — after all, that’s the very definition of poverty. And, one of the reasons child poverty is especially high is because having children immediately increases your expenses. So, the straightforward question is, what is the most cost-effective way to alleviate this problem?

Transferring money directly to parents’ pockets.

Steven Pressman, an economics professor at Monmouth University, has calculated that a child allowance of $2,000 per child per year would reduce U.S. child poverty rates by six percentage points. That plan would cost about $80 billion per year. For comparison, the federal government spent about $76 billion on the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program — what used to be known as food stamps. So, for about the cost of a single antipoverty program, we could be directly transferring $2,000 in cash to every child in America.

That may seem like a costly program. But it would actually save taxpayers money over time.

Indeed, Pressman shows that an allowance of $2,000 per year would save a total of about $110 billion, or a net gain of $30 billion, in costs associated with adverse outcomes from child poverty, such as reductions in earnings, reduction in costs of crime and poor health, and added public and private expenditures.

Once again, we find that it pays to invest in our children.

Unconditional Transfers

Right now, you are probably thinking, “yeah, but the poor will just go spend all their money on booze and drugs.”

It’s this sort of paternalism that has led many countries to place conditions on their cash allowance programs. These programs, fittingly called Conditional Cash Transfers (CCTs), are Latin America’s anti-poverty tool of choice.

CCTs give families a certain amount of cash contingent on the fulfillment of certain conditions, such as enrolling their children in school or taking them to see the doctor. Many of the programs, such as Brazil’s Bolsa Familia, are experimentally tested and funded by the World Bank and have demonstrated a multitude of positive results, such as increased earnings and use of health services.

If it were true that poor people are poor because they routinely make bad decisions, then CCTs would be the only way to go.

But studies often confirm the opposite.

Evidence debunks the myth that cash for the poor would go to drugs and alcohol. In fact, according to a British study, high-income parents were actually more likely than low-income parents to spend extra income from an increase in child benefit amounts on alcohol and tobacco. To put the point another way, low-income families prioritized spending on their children to a greater extent than did high-income families.

By contrast, Unconditional Cash Transfers (UCTs) give money to recipients with no strings attached. Experiments in UCTs like GiveDirectly in Kenya and the Youth Opportunities Program in Uganda have demonstrated positive results. The strength of the UCT design lies in the fact that more cash goes straight to families since less needs to be spent on administrative costs associated with enforcing conditions.

Cash transfers are not a new phenomenon — they’ve been a part of European family policies for decades, with the UK Family Allowances Act of 1945 allotting all families 5 shillings per week per child. Today, almost every country in Europe has some form of child benefit plan that delivers cash to mothers, and often they are both universal and unconditional.

In fact, among thirty-five economically advanced countries evaluated by a 2012 report by UNICEF, the United States was the only country that did not have some sort of child benefit plan. Given that the United States also has the second highest child poverty rate in the same cohort (topped only by Romania), we’d do well to listen and learn.

Although child poverty is a dire issue that our political system has largely neglected, a great deal of evidence points the way to policies that would be effective. Although there is no magic pill to alleviate child poverty, a variety of treatments have proven to have favorable impacts.

There is no excuse for our country’s egregiously high child poverty rate, nor for continued failure to pursue empirically based remedies.

Special Thanks to Dr. David Keller and Yolanda Minor